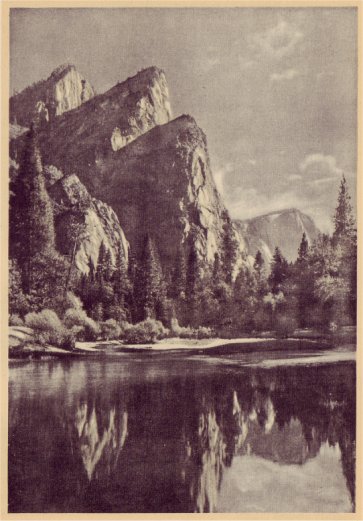

The Three Brothers, the tallest of which is Eagle Peak, 7,773 feet high, or 3,813 feet above Yosemite Valley

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Lights & Shadows > In the Beginning—Origin of Yosemite >

Next: Indians • Contents • Previous: Quotation

All of the drama of Yosemite, from its first occupancy by the Indians to the present day, is but an epilogue to that more stupendous drama, its creation. All that has happened since the birth of Half Dome and El Capitan are but the crowding incidents in a moment’s dream. What happened during the long night while the world slept? For though the massive cliffs of Yosemite Valley seem old as Time itself, geologists assure us that they are but Time’s great-great-grandchildren.

Bewilderingly long ago, millions of years, some terrific disturbance beneath the earth’s crust caused it to break and to tilt up, on its eastern edge, a great hummock of granite blocks, four hundred miles long and eighty miles wide. This was to be known, in our time, as the Sierra Nevada Range. Its eastern front, where it was heaved out of the earth, presented a steep and somewhat terraced front. Its western side was but slightly elevated, its slope gentle and gradual but sufficiently inclined to give new impetus to the transverse streams which had been flowing in diverse directions. Their course was now determined, and their combined flow began cutting canyons in the western slope of this new mountain range. One of the larger of these streams became known as the Merced River. The valley it slowly fashioned later was called the Yosemite. For numberless centuries this erosion continued until the canyon of the Merced River broadened into a shallow valley, and the Merced River slowed down and meandered lazily along its floor.

Mother Nature roused it into action again with another mighty heave, which raised the Sierra Nevada a thousand or so feet higher on its eastern edge. The process of canyon cutting recommenced for the Merced, and by the time it had lost its renewed velocity there came the third, and final, uplift, greater than all the others. This formed a Yosemite Valley not as wide, nor as deep, nor as sheer-walled as we know it now, but otherwise it was structurally about the same.

Finally, the Great Sculptor took up his frozen tools, manipulating glaciers to carve and polish to its final perfection this Yosemite Valley. Snows which had accumulated for hundreds of years packed down on the summits of these mountains until they formed solid blocks of ice. These grew and extended, sending out tongues of flowing ice into all its canyons and, eventually, forming a continuous sheet of ice which covered all the mountains and overflowed its sides.

Thus there were the ice-filled canyons of Tenaya, Merced, and Illilouette. Those three glaciers met and converged at the upper end of Yosemite Valley, to pack the canyon with their thousands of tons of grinding ice and embedded rock, as they flowed slowly down to a point just below El Capitan. Here, as the climate turned warmer, they deposited their moraine, or debris, and slowly they receded to their fountain heads in the high Sierras, damming the outlet of the canyon, leaving Yosemite drowned in a lake hundreds of feet deep. Little by little the sand and pulverized rock of the melting glaciers was deposited in this, until the lake was filled, and the present floor of the valley was formed, remarkable for its flatness, smoothness, and general absence of rock deposits.

But this was the least of the work of the glaciers. As they came and went, and while they remained, they so ground and carved the walls and floor of the valley, by the incalculable weight of the ice, and the ceaseless movement of the great blocks of rock already embedded in them, that they deepened the gorge, and changed the shape of the whole from that of a V to that of a U. With fine skill they fashioned of this rugged, humpy mountain a splendor of pinnacles, spires, domes, and arches which attracts admirers to it from the four corners of the earth

The particular and outstanding features of the Valley were determined largely by their rock structure. Where there were vertical fissures, or cleavage joints, in the walls, great slabs of granite were more easily plucked out, widening the canyon in such places, and forming the sheer, straight cliffs so characteristic of Yosemite. The quality of the rock, too, its density and its comparative hardness or softness, were determining factors in this sculpturing. Solid, only slightly fissured masses of granite, such as El Capitan, Sentinel Rock,

PHOTO BY BEST STUDIO

[click to enlarge]

The Three Brothers, the tallest of which is Eagle Peak, 7,773 feet high, or 3,813 feet above Yosemite Valley |

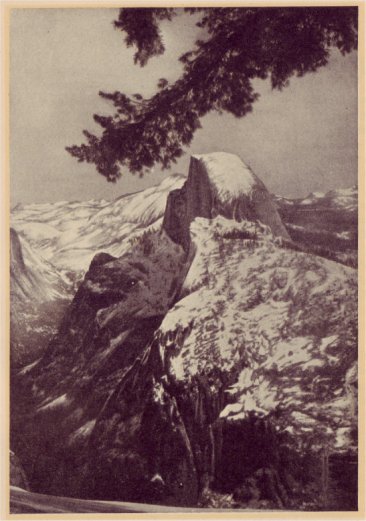

The domes and the spires and the arches of Yosemite owe their configuration and escape from glacial plucking to their curved joints. These were more resistant than the straight or intersecting joints. Many such hummocks have been rounded into domes by the heaving action of freezing water in the joint cracks, and to the shaling off of thick layers of rock, like the skin of an onion, in the natural process of expansion and contraction caused by alternate heat and cold. Most of the smaller domes, while not directly caused by glaciers, have been beautifully polished by them. Half Dome, most remarkable of all the domes, owes its configuration to the intersection of two systems of joints; one straight, the other curved. This has enabled it to withstand, through the eons, upheaval, earthquake, glaciers, and stream erosion. When Half Dome falls, probably the curtain will have gone down forever on this great stage of Yosemite, set in the course of the millions of years, and made ready for its human actors who were eventually to enact their little dramas there.

PHOTO BY A. C. PILLSBURY

[click to enlarge]

Half Dome, as seen from Glacier Point, in the winter season when snows blanket the Sierras |

Next: Indians • Contents • Previous: Quotation

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/lights_and_shadows/origin.html