[click to enlarge]

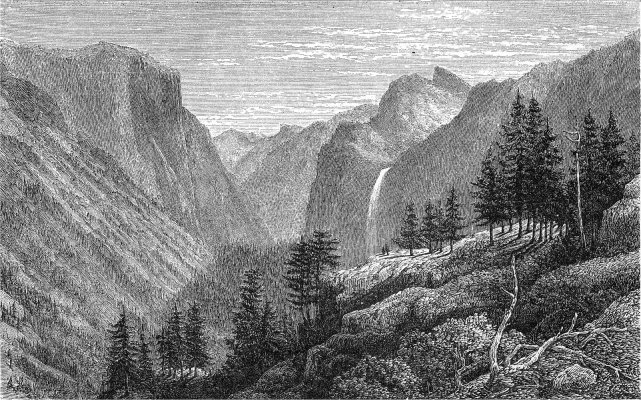

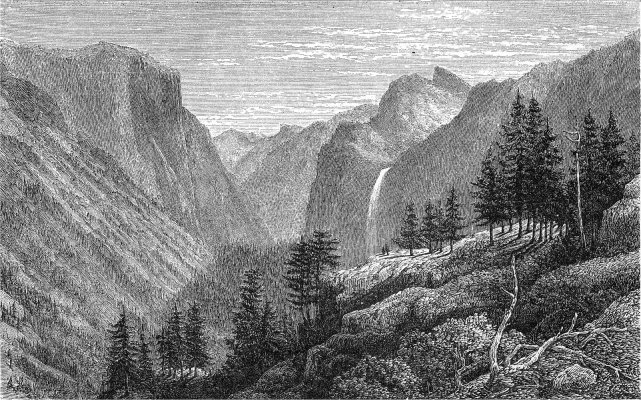

YO-SEMITE VALLEY IN EARLY MORNING

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Atlantic to the Pacific > San Francisco >

Next: Geysers • Contents • Previous: Salt Lake City to San Francisco

San Francisco.—I had expected to find San Francisco a busy, bustling city, where every one jostled against his neighbour in his hurry to and fro upon the business streets; but in a walk, on the morning after my arrival, down Montgomery towards California Street, I was struck with the absence of bustle and all confusion, although past the hour for beginning general business. The brokers and bankers all wore a look of despair, and men were assembled in little knots here and there upon ‘the Wall Street’ of the Pacific. An inquiry disclosed the fact that stocks had been tumbling for the past few days, and threatened a further decline. On Friday of the previous week (May 10), the prices of almost all mining stocks had fallen at a rate unknown before—in one case from $1,900 to less than $300 per share, and made it a day to be remembered hereafter as the ‘black Friday.’ Men who a few days before were millionaires were now bankrupts. The clouds hung dark and heavy over financial circles; and despondency and gloom filled the houses of bankers and brokers. A friend and myself made an estimate of the aggregate depreciation of the stocks upon the market up to noon that day; and our footings showed it to be not less than $47,000,000. Of course this tremendous fluctuation in value had a depressing influence upon all branches of business, in a community which is chiefly dependent upon mining interests. The shock was doubtless all the more severely felt because, as one may learn without a very long stay here, business has been overdone, and is now toiling for a legitimate basis.

During a walk along Kearney Street, a fashionable thoroughfare, I observed a strange sight—two ladies coming down the street, the one dressed in a suit of thin lawn with hat telling of summer-time; the other dressed in a gown of dark, heavy cloth, and with a long fur cloak on, and hat and costume telling of a New England winter. I seemed to be the only person who remarked this strange contrast—this evidence, on the one hand, of distrust, and, on the other, of perhaps undeserved confidence in the climate.

The architecture of the principal streets is very peculiar, ornate, and often grotesque. To accommodate them to earthquakes, the ‘Friscans’ build their blocks and houses rarely more than two stories high, and often only one.

[click to enlarge] YO-SEMITE VALLEY IN EARLY MORNING |

The people whom one meets are extremely polite and affable, and ready to show you about their city, of which they are very proud. The weather is supposed to be that of a fair May day; the thermometer is about 65°, and, when out of the sun, you are a little uncomfortable; and it is so desirable to have the sun in this climate, that you see in the advertisements of houses to let, &c., a prominent announcement that ‘the rooms are sunny.’

I was warned to prepare for the wind; and, in my walks took with me an overcoat, which by three o’clock proved most serviceable. Looking over the hills to the west, you see huge banks of fog rolling in towards the city; and the cold ocean wind, surcharged with fog, rushes upon you like an evil spirit. I shivered and hurried, and walked down streets lying in opposite directions; but still the same spirit was upon us, until I was driven into the hotel to take refuge before a glowing coal-fire in the grate. This they tell me is a fair sample of their summer weather. One may get used to it, but the first experience is very unpleasant. It is utterly out of the question to sit out of doors during the evening: little inclination is felt to walk or ride out, unless business or urgent social calls demand it.

A good dinner at your hotel does much to dispel the gloom which an afternoon’s fog creates; and the confident assurance with which the ‘Friscans’ tell you that these are their unpleasant days, and invite you to wait for their pleasant season, compels one to be satisfied, and enjoy what there is of blessings before him.

Seal Rock and the Sea Lions.—No one has seen this city, at least in the estimation of ‘Friscans,’ until he has been to the Cliff House and seen the seals. No matter how cold are the blasts which blow in from the Pacific; no matter how fearful are the showers of sand, or even how angry look the skies, the Cliff must be seen; and a drive over the Cliff House Road is indispensable to a proper reception into this wonderful town. At breakfast, upon my first morning in the city, I was asked, ‘Have you been out to the Cliff?’ Therefore, on the second day after my arrival, I made this pre-eminently necessary excursion. The drive of a little more than a mile through the city was a kind of martyrdom. The fine sand from the hills round about fills the air, and, borne upon the Pacific blasts, cuts the face until we cry for quarter. These sand-hills were blown up from the ocean beach; and their position seems to be constantly changing. The streets often run through these sand-banks; and, if you plough through one, you then can understand what a sandy road is indeed. In places, where the streets have been graded and macadamised, the sand comes in, and repossesses itself of its old quarters, covering side-walk and carriage-way, door-step and front gardens.

By dint of courage and perseverance we succeeded in getting beyond the city street proper, and upon the famous road. As there were races at one of the agricultural parks, the road was unusually lively and gay; and we had the pleasure of seeing the ‘fast nags.’ The road is nigh three miles long, and has a hard, smooth carriage-way, in width some 60 feet, and a trotting track-way of some 40 feet; and the whole is kept in most perfect order from the funds received at the gate, the toll being four ‘bits’1 each carriage. As a road, it is of great merit. The drive is almost wholly without interest, unless it be to watch the varied surface of the great sand-banks made by the wind, or look over a field and observe the ripples and the changing colours in the sand which has been blown up from the beach. The road takes a sharp grade down towards the beach, and, by a very nicely curved way, you are let down to the level of the Cliff House Piazza; and a short distance more brings you down upon the sandy beach.

1A ‘bit’ is an old silver ninepence; and so the toll is a silver half-dollar each carriage.

The Cliff House is a wooden structure built out over the rocks, and has evidently been enlarged as business increased. It is neither pretty in its architecture nor inviting in its appearance; but inside the house creature comforts are dispensed with lavish hand. Standing upon the veranda looking out to the ocean, you have, a little to your left, the great Seal Rock, whereon disport the sea lions—now crawling up the rocks, their sides dripping with the foam; now stretching themselves out in the sun; and now rubbing their sides with their fins, which serve them as paddles, hands, and feet; or now again lashing the rocks with their tails, all the time growling, or rather howling. Their antics afford much amusement to the people who throng this popular resort.

Among the lions which have grown old and ill-looking, in the service of entertaining with their strange freaks and pranks the populace of this fun-loving city, is one whose eyes now squint from over-feeding, who seems to rule the rock with the greatest bravado, and is called ‘Old Ben Butler.’ For the peace and good of the other lions, may ‘old Ben’ soon take his last leap into the sea!

To our left is Gull Rock; further around are the Headlands, and to the right, the gate called Golden, through which all the commerce of this port must enter, and through which our ships seek a path to China and Japan. The hills, where they are of rock, rise majestically from the sea; and with the air free of fog, and at setting sun, a beautiful picture is seen here, and this narrow roadstead found to have been rightly named the ‘Golden Gate.’ For miles, you may ride along as pretty and sandy a beach as you could desire. The ocean dashing at your feet, or surging against the projecting rocks, tells us of our ‘other ocean’—the blue Atlantic. Navigators called this the ‘Pacific’ because its waters were so calm; but they only knew of its Southern character. Then they had not been far enough North to determine whether California was an island or the mainland; and, indeed, upon early maps which I have seen, it is laid out as an island. If you desire to test the ‘pacific’ nature of its waters, you are told that a voyage North, to Portland, Oregon, or to Alaska, will settle the question; and you will only wish that Drake, and his compeers, had sailed further North before they named this great ocean, the Pacific. Its waters about San Francisco are evidently not so blue as those of the Eastern coast, neither are they so clear; but this, undoubtedly, is caused, to a considerable extent, by the mining, which sends down into the Bay so much soil and decomposed rock.

A delightful drive took us back over the road, and through some of the best-built streets of the city, to our hotel, as thoroughly initiated into the mysteries of the Cliff House, and the famous road leading to it, as is a hazed Freshman into the great mysteries of college life. Let not anything here written deter you, however, from taking this drive, lunching at the Cliff House, and taking a. sight of ‘Old Ben Butler,’ should he still live to torment his enemies, and disgust his friends, when you visit California.

On the morning of my first Sunday in San Francisco I was awakened by the sounds of martial music and the tramp of soldiery. For a time I thought it was the Fourth of July. From the hotel-window I saw no less than three military companies, each with a band, marching on their way to some picnic. The side-walks were thronged, by eight o’clock, with men with wives and children, oftener, perhaps, with their sweethearts, hurrying to the boats, the cars, the ‘buses,’ and every sort of conveyance which would take them to some ‘place of resort,’ or into the adjoining country. The horse-cars were all placarded with advertisements of shows and performances at ‘Woodward’s’ and the ‘City Gardens,’ the theatre and the circus. Used to the staid customs of our New England cities, I was a little bewildered at these sights, but was told that Sunday was the great holiday for the people—perhaps to-day a little more parade; but still that every pleasant Sunday takes the people into the country, to the islands in the Bay, or to that greatest of all great places—Woodward’s Garden; for Woodward is the California ‘Barnum.’ He is better known among the mining population of California as the proprietor of the What Cheer House. Later in the day I found that there was a large church-going population, and by service time the city became as quiet, and was all day as orderly, as any in the East.

Views of the City.—As is well known, San Francisco is greatly exercised of late about the occupation of Goat Island, and the building of a rival city on the Oakland side of the Bay; and I must say that, to one unacquainted with the early history of the city, the site where Oakland is built seems the place for the great city of the Pacific. The deeper water-front of the early days determined the commercial superiority of the site selected, aided, and perhaps assured, by the Spanish mission-church and fortifications, then already established. The city has moved away from the deep-water-front, and is finding its commercial marts far to the South, where they must fill out into the Bay for the wharves, that ships may have protection from the gales which at some seasons of the year prevail.

Oakland Wharf is a favourable point from which to get a panoramic view of the city and harbour. The wharf extends out so far into the bay, there is nothing to obstruct the vision. The atmosphere is so much clearer than in England, that one accustomed to that foggy air, is surprised to find his range of vision so extended and the outlines of objects brought out with such distinctness.

From this point, looking west, you have, just by that huge rock which rises from the water about a mile from the end of the bridge, called Goat Island, and which has given so much trouble, the roadstead which leads out into the Pacific, through the Golden Gate. To the left rises Telegraph Hill, whereon, in early days, the beacon-light was placed, and at the foot of which the early miners pitched their tents, and began their city. For many years the business portion of the city lay at the very base of this hill, with the tents and cabins of the new-comers far up its sides. It seemed to me, now, that I could see the scattered tents of the primitive town, and the good ship ‘Niantic,’ in charge of Capt. Brewer of Boston, gracefully sailing up the Bay, to become the first hotel of the city. I saw the little settlement increase from hamlet to town, and from town to city. I saw her people gathered in the plaza, witnessing the fights of the bull and the bear. I saw snips flying the flags of every nation coming to the new-found harbour, bearing the living freights, and carrying away the golden treasure.

Now the city has stretched away to the South,—as far as Mission Bay, and to the West two miles, and more, towards the Ocean. The place where the ‘Niantic’ used to lie is now covered by a large brown-stone block of stores; and to the East, for nearly a mile, the Bay has been filled in to find deep water, and the whole space covered with large, and, in many instances, substantial storehouses. Around Telegraph Hill decay has attacked both the buildings and the dwellers therein; the stores have been emptied of their merchandise; and but little now remains to tell of the bustle and noise of the early settlement. The plaza has been inclosed by a neat iron fence, and beautified with trees and shrubs, to remain for ever a park, to which the old inhabitants love to come and think over the scenes of early days. As you look upon the city, you see the shipping, with flying banners, at the wharves, war-vessels riding at anchor, then long lines of storehouses which cover the low land West to Montgomery, next the Mansard roofs of Montgomery and Kearney Streets, and above them the clock-tower on the Chamber of Commerce, on California Street, come in view. Rising above the city is the bald form of Telegraph Hill, and, to the South, the house-capped sides of Russian Hill. Further to the South is Lone Mountain, where they have laid out a cemetery; and then the land stretches away in a gentle slope to Mission Bay, with the foothills separating the ocean from the Bay to the West. To the extreme South are the China Docks; and away down the Bay is seen the dry dock and South San Francisco. The open sea is not visible, as the city is situated upon the Southernmost of two ridges, or arms, which jut out towards each other, cutting off the view seaward, and leaving only a narrow pass between them, thus forming the ‘Golden Gate.’ To the West of all rise the great sandhills, over which we must pass to reach the ocean. In the summer months, generally, a fog-bank, after ten o’clock in the morning, hangs over the Western suburbs, ready to be taken over and upon the whole city by the trade-winds, which prevail at this season of the year.

Montgomery Street, running from Telegraph Hill, South, to Market, is the principal business street. Kearney, the next street West, and parallel with it, is attracting the shopkeepers whose trade is with the women. New Montgomery, which was to be an extension of the old street of that name, and upon which one front of the Grand Hotel is erected, was an unfortunate enterprise for its projectors, many of whom have been ruined.

The streets in the business portions of the city have wooden pavement; those in the sparsely settled portions are macadamised. The sidewalks are nearly all of plank, save upon the principal business streets, where all kinds of walks may be seen. Many of the streets are so steep, that it is with difficulty that one can drive up or down them, Clay Street being a pretty good test even for pedestrians. The horse-cars are compelled to make long détours around these hills; and, even then, four horses are often required to draw a car up the grade.

I cannot speak very favourably of the architecture of the city. Around the old adobe church of the Mission Dolores many of the old clay houses still remain, bearing the marks of a century. The dwellings are not generally elegant, and stately mansions are rare. Small, one-story, three-roomed houses are occupied by the people. Recently some fine private houses have been erected; but all seem very unhomelike in their exterior appointments. The public buildings are so out of proportion, that they exhibit no architectural beauty. House-builders seem to have accepted the situation,—that every October the earth will quake, and that masonry will crack, and ceilings and chimneys will fall: hence they have sacrificed taste to a style which they call ‘earthquake proof.’ The great hotels—the Lick and the Grand—present long and somewhat imposing façades; the Occidental has the most harmonious front, but is considered too high for that ‘peculiar institution,’ an earthquake. The newer buildings are of wood; and all are covered with ornaments, to such an extent that they become often very repulsive. The structure which the Bank of California has erected for its offices, although neither large nor pretentious, is, to my eye, the best specimen of graceful and classical architecture. The Treasury Building of stone, in the Doric style, has just been completed, and compares favourably with the Government buildings of other-cities. The new City Hall is not far enough advanced to decide its merits, although the plans show a very elaborate, but still very ornate design.

The churches in their architecture are not as a whole pleasing. Several new ones, among them Dr. Stone’s in Post Street, are fair in their proportions; but there is in them all a lack of harmonious blending of materials used, and in the adjustments of the lines of gables, windows, and doors. The Episcopal church is almost ugly in its appearance; Calvary is better, but has the look of an opera-house. The church which the lamented Starr King designed, and in which his society still worship, has a pleasing and harmonious Gothic front. This edifice also in its interior finish and arrangements shows the cultivated taste, as well as the wisdom, of its architect. Just outside this church, within the little yard, separated from the street by an iron fence, and beneath the shade of a Monterey cypress, is the sarcophagus which holds the cherished dust of Starr King. New England gave of her best when she sent this eloquent divine, in the trying hours of need, to the Pacific. He infused his own life and teachings into a people who now hold his name in honour, and revere his memory, telling their children of him whom they loved so well. This done, his mission seemed ended. The memory of his life and his recorded utterances remain a perpetual legacy to the people of the state of his adoption as well as to those among whom his labours began.

In riding about San Francisco, one is amazed with the luxuriance of foliage and blooms which are seen in the gardens. Hedges made with the fish geranium fuchsias trained against the house, reaching above the windows, or in a tree, with stern four inches in diameter the century-plant in full bloom; the tea roses, pelargoniums, and the choicest pinks, all growing out of doors without protection—such are some of the sights. There is a lack of shade-trees along the streets; but in the gardens I saw the pepper-tree, with its delicately-fashioned leaves; the cypress, with its feathery foliage the eucalyptus, from Australia, which grows very fast, and is said to rival in size the sequoia (of which species are the ‘big trees’ of California); the fig; the several varieties of palm; and choice evergreens, the arborvitae, the cedars, and many other trees, all growing in luxuriance. As there are no grasses indigenous to this region, much difficulty has been found in making lawns; but some of the southern grasses, like Kentucky red-top, the Timothy, together with the white clover, have been made to grow upon prepared soil, with constant irrigation; for even here a windmill is almost as common, and certainly as useful, as in Stockton. The lawns, however, are not like those which give to the English country places their special charm. As you look at these plants and trees, growing the year round, it seems that they must be tired, and need a Northern winter to sleep away a part of the year.

The schools I found much better than could have been expected. By the kindness of the superintendent, I was enabled to visit several of them. The scholars are much further advanced at the same age than with us. They excel in the languages. We found children of ten to twelve years speaking quite fluently French and German, and those, too, who hear only English at home. They show great talent for the drama. In the rendering of selections from the authors, they not only spoke well, but acted well, and brought into play accessories in costume and furniture in a manner creditable to an Eastern Amateur Dramatic Society. Much prominence is given to instruction in instrumental and vocal music.

There is in the city but very little manufacturing of any kind. The Mission Woollen Mills are now, by the union with the Pacific Mills, and by using Chinese labour, enabled to keep their machinery running. The market being so limited, they are forced to produce a great variety of fabrics, among which the ‘Mission blanket’ is justly celebrated the world over. Some few shoe-factories are carried on with Chinese labour; aside from these, but little is done: and Chicago—now so near, since the railroad was completed—is made to supply what the city ought to produce within itself. The click of machinery, the hum of the loom, and the puff of the steam-engine, all are lacking, which make Eastern cities so full of life, and which tell that within our workshops are being fashioned the most curiously-formed products, both useful and ornamental, which other States will need in exchange for the farmer’s grains and cattle.

As is well known, California, unwisely as it seems to us and, now, to very many of her people, refused a paper currency, and has to this day used only gold and silver. That they are now learning that a paper note, when duly honoured, is more convenient for use than coin, is at last acknowledged by the bankers and merchants in the demand for a national gold bank, which has recently been established, and whose issues, in lieu of coin, are eagerly sought for by the people.1 The smallest piece of money used, after the early custom of using gold-dust ceased, was an old ninepence (twelve and one-half cents), which was always called a ‘bit.’ A quarter of a dollar was a ‘two-bit piece,’ a half dollar a ‘four-bit piece,’ &c. Now that this coin has departed, and the nomenclature as well as practice remains, a great difficulty is experienced. If you buy anything for a ‘bit,’ and hand a quarter of a dollar in payment, they return you ten cents in change, which would be, as they say, ‘taking the long-bit; ‘the ‘short bit ‘being a dime. A person who tenders a dime for a ‘bit’ is stamped as a mean man, and is avoided: so, what is demanded is, that you should try to pay about equally long and short. No nickels1 are seen, and very few silver half-dimes. The leading bankers, I think, are now satisfied that it would have been better to have adopted our common currency; and, if this State had done so the difference between gold and greenbacks would have been long ago made up by the general confidence in our paper. I discover two reasons which determined the course: first, as the people had always been accustomed to gold coin, never having used paper currency, it was a difficult matter to effect a change; and, secondly, it must be said, although I regret it, that there was a large and very influential minority who were favourable to the South during the late civil war, and averse to the use of the ‘war-issue’ of currency. The bank of California is the leading financial institution, wielding an immense influence, and presided over by Mills and Ralston so ably, that it has the confidence of the entire financial world.

1Two Note Banks are now doing business, and others are projected.

1American five-cent pieces.

The street-cars are of all sorts and sizes,— two-horse cars, four-horse cars, and one-horse cars; and the prices for riding in these conveyances vary, like the cars, from three cents up to seven cents. As there is little small silver and no cents in use the passenger is forced to accept tickets in settlement of the balance of the dime (ten cents) which he has presented the conductor, for his ride. The consequence is, that, after you have been in ‘Frisco’ a few days, you have a collection of car-tickets, Which, for variety in shape, colour, and printing, cannot be surpassed. The roads do not generally exchange; but the three-cent line takes a seven-cent ticket of any other company. How the people submit to such inconvenience, it is hard to say; but I suppose a horse-railroad company is substantially of the same genus in ‘Frisco’ that it is in—say Boston.

‘Fighting the Tiger’ is the phrase used for gambling. In the early days of the city, all the people spent their nights around the gaming-table, and with the miners, even although they have now become rich, the love of Faro remains. There are in the city numerous dens where you can loose your money almost surely, although Californians boast of their ‘square-game.’ What was once done openly is now carried on in defiance of law. With the old population gaming is a pastime, and they stake their money with that recklessness which is born of becoming suddenly rich, and with the numerous prizes in gold-mines still undrawn. Admittance to a Faro Bank is easily obtained, and as a warning in nearly all the dens you will see hanging upon the wall a tiger’s head with open jaw, ready to seize his prey. Once having ‘bearded the lion’ they say this becomes only a pleasing picture—a wall decoration.

The Chinese.—If ever there is a study which repays one, it is to learn of this curious people, who, transplanted from their ‘native heath,’ are trying in this foreign land to preserve the customs of their country. Meeting with many difficulties, suffering much, working hard, they still succeed in maintaining their own ‘Joss House,’1 their own theatre, and in not mixing at all with the white race. There are, at present, more than twelve thousand in San Francisco. Although there are large monthly arrivals, the demand for their labour in the country keeps the average very nearly the figures stated. They swarm in the section around Sacramento Street, and are scattered throughout the city. For the most part, they are sober, kind, and submissive, and in certain places they are exceedingly valuable as servants. It is the custom here to have a Chinaman as chambermaid; and your cook is ‘John,’ who—arrayed in neat blue tunic, with pigtail, black and neatly braided, reaching to the heel of his thick, cork-soled slippers, and whose big trousers at least hide ungraceful legs—goes about his work without bluster, and sends to your table dishes exquisitely prepared. Your dinner is served by a ‘little John,’ in tunic as white as snow; and your garden is weeded by another, in a hat so large, that, looking down upon it, you see no ‘John,’ or any thing else save bamboo braided into a peculiar shape.

1The name given to their temples of worship. There are three rival houses in the city, but within they appear exactly alike.

The Chinese have monopolised the laundry business; and in this they excel. You see around the city little signs over little doors in little buildings, upon which is printed ‘High Lung, Washing and Ironing; Hup Lee,’ Quon Lee,’ ‘Hi Boo,’ or ‘Le Chung,’ either one of whom will come for your linen, and return it in a short time nicely prepared, and at very low prices. Chinese servants quit without notice, or without giving any reason for so doing; but, aside from this, a large majority of them are faithful at their work, quick in learning and exceedingly neat.

They are addicted to gambling; but theirs is the only fair game that I ever knew to be practised for this purpose. It is simply this: A grave-looking Chinaman called the umpire sits at the head of a long table, before him a large heap of checks or chips, round, with a hole in the centre: a handful of these is taken up, and laid away nearer the centre of the table. Upon the left of the umpire sits the banker, who now wagers something, from his bank,—seldom over fifty cents,—that there is either an odd or an even number in the heap. Some one of the crowd now wagers as much money as the banker against him. If any other one bets, then the banker must advance the same amount; the money being laid upon a little board marked off into squares. The customers use representatives of money; while the banker lays down coin. When all are done, the umpire, with ivory stick slowly. draws the checks one by one from the pile, and places them in twos back in the large pile. The experienced eye of the Chinaman, long before they are all drawn away, will detect whether the number is odd or even, and so whether he has won or lost. This causes a general talk in a most animated manner. After the games are closed the patrons of the establishment settle for their checks.

The banker would seem to have no advantage, save a small fee which is charged for the privileges of the house; and, if people must gamble, the plan of the Chinaman is highly recommended. It is by far fairer than the modes adopted and practised in that great den at Saratoga, or at any other gambling-saloon, if I am rightly informed by ‘those who have been there.’ Bret Harte’s Chinaman had evidently learned all his tricks from some old Californian, who, being about ready ‘to pass in his checks,’ was willing to tell others ‘how it was done.’

Many of them are intelligent, and come from home with a knowledge of simple English words: all of them know how to read in their native tongue, to count, and to keep accounts. I made the acquaintance of many Chinese gentlemen, not only of intelligence, but of culture, and whose friendship I prize.

The Chinese live very frugally; rice and pork forming their chief food, with chickens, of which they are passionately fond, when they can get them; and often their last bit’ goes for a bit of chicken. Tea is their favorite drink.

We lunched one day at the fashionable Chinese restaurant, and, for the first time in our lives, learned what a good cup of tea is. We could not use the chop-sticks, so we could not eat rice; but we took from a tray, filled with nice-looking food, which was brought us, some very delicate cake with almonds in it. This was the place where the wealthy Chinamen lived; but in the other restaurants the food looked good: but of course, as in all such communities, there were places where you would not believe that anything deserving the name of food could be obtained. At night the great mass of them huddle together in the smallest space.

They keep innumerable little shops. The doctor has his filled with all sorts of barks, leaves, and berries; the tea-man has his teas; the grocer has his supply of China-packed goods, including jars of the choicest ginger; the butcher has his stall full of the most curiously cut bits of pork, often smoked black, chicken, and fish; the clothier has his tunics, trousers, hats, caps, and slippers. The great tea-merchants have simply an office, as they deal only in large quantities direct from China. There is among them an artist, who paints in oil, or photographs with Chinese accessories, doing creditable work. Their theatre is a favorite place of amusement; and the piece which is now on was begun at the opening of the house, years ago, and will occupy many years more to compete it: hence the necessity of going often to keep up an interest in the play. This ‘China Theatre’ is situated in Jackson Street, and is one of the strangest sights in the city. Words would fail to describe the grotesque scene inside the house. Of the playing there is no standard of comparison—it is wonderful, exceptional, indescribable.

Their ‘Joss-houses’ are attended daily but especially upon fête days. Here they have their hideous images of the good, the evil, the pretty princess, the man cast out of heaven, the great prince, &c., before all of whom the sandal-wood taper is kept burning, and dishes of food in great abundance are placed for the gods to eat. Adornments of odd designs cover the sides and ceilings of the rooms; and a great bell, which is beaten at times of worship, stands near the door. These temples are presided over by a soothsayer, who sits in his little room adjoining the door, and writes out the teachings of the gods. As he works he mutters to himself the words of the legend. Around sit other Chinamen engaged in hearing the will of the god whose image is in sight.

The whole of the Chinese religion is simply this, stripped of its form of development: They believe that there are two spirits,—the good and the evil. The good cannot do harm in any way; as it is good, it can do only good: but the evil, while it cannot do good, may not do bad; so they try to appease the evil spirit, that it may not exercise its terrible power. This they do chiefly by keeping him well fed, and by following certain rules of life, which traditions from the old philosophers have taught them to be the proper way to live, that after death, if the evil spirit does not come, they may dwell in peace and happiness. But in heaven, constant care must be taken lest they may be cast out, like the man whose image is always set up in their Joss-house as a warning. There is a deep philosophy in their religion, which Confucius gave them, and which, with the lapse of time, they have not lost. The Chinese are honest,—a trait which seems to be a part of their natures. A close study of them for five weeks leads me to hope that we shall soon have them more numerously in the East, not to come into opposition to any form or kind of labour nor to injure any class, but to take their places side by side with all, and do their share of the labor, which is far more rapidly increasing than are the hands to do it. As soon as the present labouring-classes of the East understand them, they will cease their opposition, and allow them to take such places as they are fitted for. When we consider the grape-growing interests of California, we see how advantageous they have been, saving from utter ruin an enterprise of which now the whole country is proud, and continuing it in prosperity where no other people could or would work.

So my voice is for the Chinaman, praising his virtues, and dealing leniently with his many faults.

Before closing what I have to say about San Francisco, mention ought to be made of the hotels. No city is better supplied. The four large houses—Grand, Lick, Occidental, and Cosmopolitan—offer pleasant homes. As the Grand is new, it is filled with tourists; the wide-spread reputation of the Occidental brings all the business-men to its halls; while the Lick is a great family boarding-house, whose magnificent dining-room used to be thronged with the élite of the city. Hotel life is not so general as it was formerly; and, the supply being greater than the demand, hotel property is at a sad discount just now. It is often stated that you can live cheaper in this city than elsewhere; but this applies specially to food, for clothing and rents are higher than in the East.

The Californians are, as a class of people, very hospitable and free, live easily, and spend their money without stint. Such a people demand places of resort; and they have them in this city in every form,—gardens, theatres, circuses, saloons, skating-rinks where a polished floor takes the place of ice, and restaurants where choice viands are set before you. Liquor-drinking is here perfectly open and free; and the bars are fitted up in the most elaborate and costly manner, with choice woods worked into the artistic panels and mouldings, with mirrors of costly plate, and with all the appurtenances of the bar in pure silver. There are at all the bars, during certain hours, free lunches; and in some places on and near California Street, you can, by purchasing a glass of wine for two bits (twenty-five cents), obtain a good dinner. It seemed a contradiction that a man could make profits and carry on such an establishment; yet they succeed, and are making fortunes for their proprietors. During the whole day, drinks are dispensed; but the price is always the same,—twenty-five cents. There are other places where a dime is charged, and where the lunch is less elaborate. All are carried on in the most orderly manner.

In the East, we drink behind curtains and screens; here in a room carpeted with Brussels, and furnished with velvet cushioned chairs, and open to the street by plate glass windows and doors. During my whole sojurn here, only a few intoxicated persons have been seen. These facts are stated, not to favour the use of liquor, but that some lessons may be drawn to aid the suppression of an evil which has become such a curse.

The city is too young to have many libraries, picture-galleries, or museums. The Mercantile Library and the Mechanics’ Institute are both creditable, and offer to their members the advantages of pleasant reading-rooms, and well-filled libraries. The patronage given to them shows a growing interest among the people for reading.

‘The Pioneers’ is a society composed of all those who landed in California prior to the first day of January, 1850. It has a fine hall, offices, reading-rooms, library, &c., in a building owned by it on Montgomery Street. Here are preserved the trophies of the early days of California; the old ‘bear-flags ‘adorn the walls; and in these rooms are nightly gathered those whose names and deeds are closely connected with the founding and early history of the State. It was a rare treat to visit the rooms of this society, there to meet the very men of whom I had read, and hear from their own lips of the struggles and hardships which surrounded the birth of the State, and those still harder struggles which freed the country of the desperadoes and ruffians who so long infested the Pacific Coast.

The Bohemian Club is composed of the artists and literati of the city. Their kindness in giving me the freedom of their elegantly-furnished rooms added much to the comfort and happiness of my visit. In their cosy parlours, every afternoon, after business, and during the evening, are gathered genial spirits; and the hours glide away so pleasantly, that all cares are forgotten, and upon the faces of all hang

|

‘Wreathèd smiles,

Such as Hebe brings.’ |

Who could fail to be happy with the Bohemians? May success and prosperity attend the club! for, without it, a visit to this city would be robbed of much of its interest. They seem to carry into practice the German saying, ‘He who creates a laugh creates forgetfulness; and he who creates forgetfulness distributes oblivion.’

I had the great pleasure of attending, on the evening of June 18, the first reception of the Art Association. In well-appointed rooms on Pine Street, which the Association have fitted up for a permanent gallery, were gathered the artists and their friends, a brilliant assembly, to view the pictures. The pictures were not numerous, and many seemed badly hung: still, for the first reception in a new city, and so far from the great art centres, it was very creditable. Bierstadt, who is staying at San Raphael, a few miles from the city, is represented by ‘Mt. Hood’ and ‘Cathedral Rocks in the Yosemite.’ His ‘Mt. Hood’ is a grand picture, and full of those pleasing ‘bits of painting’ which he can so well put upon canvas,—as in this, the herd of deer browsing and feeding upon the margin of the quiet lake. Thomas Hill, who is for the present here, sends ‘A View from Point Lobos,’ in which you see the great waves of the Pacific dashing against the cragged rocks and among the deep caverns of the shore. Kidd, formerly of Albany, but now located here, gave two very pleasing pictures, of which one, ‘A Dead Mule on the Prairie,’ was, in drawing and detail, a capital work. Brooks sent two exquisitely-painted salmon, and several still-life pieces. Loomis placed upon the walls a landscape, which, though it failed to attract much attention, still was as choice coloring as any of those exhibited. A picture by this artist in another place, and some pencil-drawings, gave us much satisfaction. If I mistake not, Mr. Loomis has charge of the drawing in some of the public schools. Irvin presented a portrait of the poet Miller; and Champion and Tojetti also contributed portraits. These, with a large number of old master-pictures, said to be originals, from the collection of the late Mr. Pioche, together with a few pieces of sculpture, formed the chief art attractions. I speak of this exhibition to show what a cultivated taste exists in the city. Although young, San Francisco can rival many of her older sisters in the fame of her artists, and this, the first, general exhibition of the Artist Association was a success beyond the expectations of its promoters.

Goat Island.—Undoubtedly you have known something of the great excitement which has stirred this city, caused by ‘The Goat Island Scheme,’ as it is termed, and the question of ceding Mission Bay to the Central Pacific Railroad Company. Rather than take anything at second hand, I had an interview personally with Gov. Stanford, and took occasion to discuss this matter. The city, as I understand (it being almost impossible to find any two who alike state their grievances), feels alarmed, lest if Congress should grant the railroad company even the use of Goat Island, it would be immediately levelled down, and a city, as a rival to this, be built there, and all the freights over the railroad be transhipped at its wharves, that the China steamers would make their terminus there, —all having a tendency to lessen the importance of San Francisco. The completion of the railroad has injured business, and hence lowered the value of real estate. New York now is within seven days of here, and other markets proportionally near. Buyers instead of being forced to San Francisco, now find their way to the great metropolis, and other Eastern cities. This feeling of depression only makes the people the more sensitive to any thing which may injure their city. They have a committee of one hundred, with chairman and secretary specially charged to look after the interests of the community.

The Mission Bay matter is this: The city gave to the company the land of this Bay to be filled out to a deep-water-front, to the extent of some sixty acres; and through this tract streets and avenues had been surveyed and plotted. The company asked the board of supervisors to pass an order giving it those streets and alleys. The resolution as worded was rather indefinite; and the people think, that, under this cover, it is endeavouring to obtain a perpetual grant of this bay and India and China basins, freed from all streets. So much for the people’s side of this fight, the magnitude and bitterness of which can hardly be conceived by one who has not been here.

Gov. Stanford says, ‘The bill now pending before Congress asks that Goat Island be appraised, and rented to our company; the government to reserve the right to repossess themselves at any time. The fight has arisen more between the land speculators at Ravenswood on one side, and Saucelito on the other; and the city between is made the apparent antagonist of the company. By a new road we can reach Oakland in about 87 miles from Sacramento; the road now through Livermore Pass being 137 miles. For this reason, we want Goat Island, that we may level down its outer edges, and erect storehouses thereon. It will bring us a mile nearer our business in the city,—Mission Bay. From here to our business, we should be obliged to use a ferry, as we do now to Oakland Point. Goat Island is a barren rock 380 feet high, situated in the bay about 4 miles from the Oakland shore, and its nearest point only five-eighths of a mile from the present wharf from which the ferry starts. We intend to approach the city of San Francisco by three main lines,—one from Humboldt, Oregon, and all west of Sacramento, centering at Saucelito, and thence by ferry to the city; all east of Sacramento and the great valley of the San Joaquin, to Oakland as now; the southern roads, including the Southern Pacific lines, by rail direct to the city by way of San José. As a general principle, business must reach the city by the shortest and most direct route, and by the easiest grades. It is folly for the people to say that we intend to level Goat Island, and build a city there. It would not pay us to do it: our business is in San Francisco. We have already real estate and improvements there valued at more than 4,500,000 dollars, and this city is our terminus; and there never has been any intention of making any other place or places the real terminus of our roads. This whole panic, which has so disturbed the people, is a foolish, unnecessary, and wicked plot; and those who are aiding this excitement, which is so injurious to the trade and prospects of the city, are criminally to blame. I have faith in San Francisco and her people: I shall oppose them only so far as self-protection of our road is required, believing, that, in time, they will see the right, and understand the motives which have actuated me, and the officers of the company, in the course which we have pursued.’

Thus rests this quarrel, which is and has been so injurious to both city and company.

Although I find that the dreams of the people about the effect of the railroad across the continent have not been realised, although all business is stagnated, lands less valuable than before, business-property sadly depreciated, and the people disheartened, still San Francisco is plainly destined, by a slower but steadier growth, to march on to a grand national importance. The great valleys will send to her storehouses their unmeasured yield of wheat; energy, and better knowledge of the manner of working the mines, will force the mountains to yield up their treasure; the wine-growing interest will add to her wealth; the South will contribute its varied fruits and nuts; ships from China and Japan must find here a port; and soon, I have no doubt, Australia will send her mails and treasure to this port, to be conveyed across the continent to the steamers at New York. Thus it is that San Francisco must ever remain the mistress of our Western ocean.

I take my leave of San Francisco by addressing to her these beautiful words of her own poet, Bret Harte:—

|

‘Serene, indifferent of Fate,

Thou sittest at the Western Gate.

Upon thy heights so lately won

Thou seest the white seas strike their tents,

And, scornful of the peace that flies

Thou drawest all things, small or great,

|

Next: Geysers • Contents • Previous: Salt Lake City to San Francisco

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/atlantic_to_the_pacific/san_francisco.html