Yosemite > Library >

Vacation >

“Basket Makers” (1901) by George Wharton James

Cover, Sunset (November 1901)

|

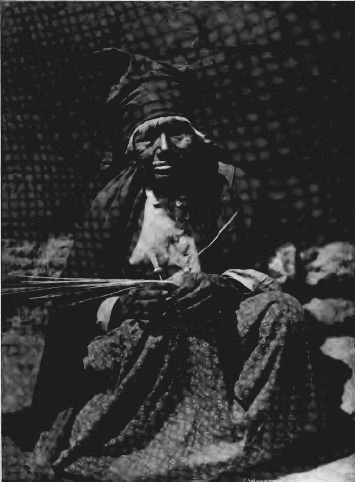

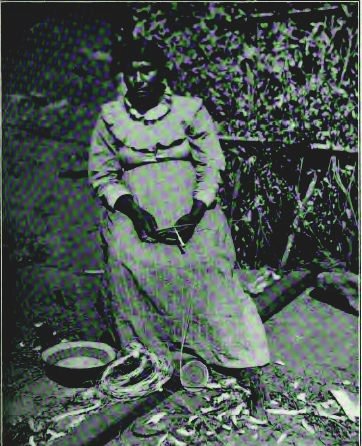

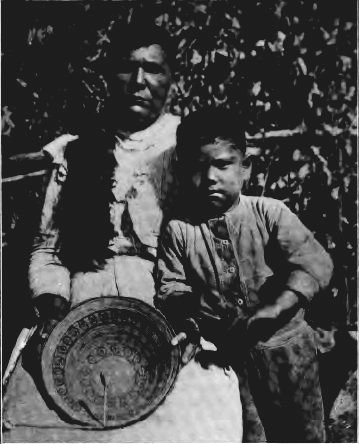

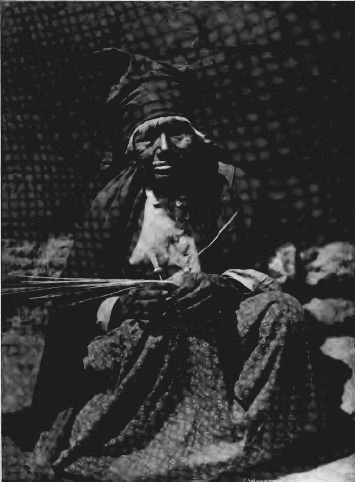

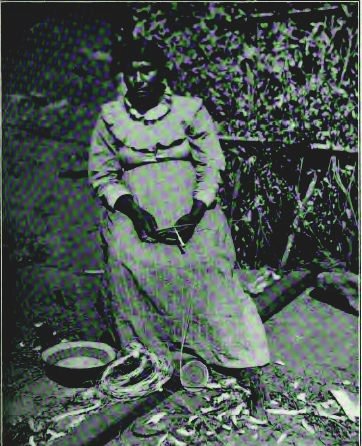

MARIA ANTONIA, ONE OF THE MOST EXPERT OF THE CAHUILLA, CALIFORNIA, BASKET-MAKERS. WHEN THE

PHOTOGRAPH WAS TAKEN SHE WAS JUST BEGINNING AN ELABORATE BASKET. CAHUILLA HAS BEEN MADE

FAMOUS BY THE REFERENCE TO IT IN MRS. HELEN HUNT JACKSON’S “RAMONA.”

|

|

|

Vol. VII

|

November, 1901

|

No. 1.

|

Illustrated from photographs by the author.

Three exquisitely woven baskets in

the Plimpton Collection, San Diego

|

Basketry

is a primitive art.

It is found among all primitive

peoples in some form. or other,

and in the remains of the most ancient

people. From the tombs of Egypt

baskets have been taken, made at the

time when Moses and Aaron appeared

at the court of Pharaoh, or even before Abraham became a wanderer on

the plains of Kadesh and Shur. The

earliest visitors to Asia found basketry,

and when the Columbian discoveries opened up the new world of

America, every tribe was found to

have its expert, basket-makers, from

the farthest region in the south to

the highest point reached in the

north. And it was not an art found

in a rude and primitive state. It was

highly developed, and, indeed, was

then in its days of glory—a glory

never since surpassed and seldom

equaled.

To the Californian it must ever be a

fact of great interest that nowhere in

the world was the art of basket-making carried on with greater skill

and success than in his own state.

From north to south the native Californians were all more or less expert

YOSEMITE INDIAN’S ACORN STOREHOUSE

|

basket-makers. The Pomas in the

north were equally proficient with

the Palatingwas in the south, and,

though it must be confessed that the

art of basketry is on the decline, it is not less certain that

the California Indian of today

holds a very high position

among the existing basket-making peoples of the world.

It is not my purpose in this

short article to present a comprehensive survey of the whole

field occupied by the California

basket-maker. I have neither

the knowledge nor the ability

to do this. Of one tribe alone,

the Pomas, Dr. J. W. Hudson,

of Ukiah, has written, with a

wealth of knowledge and

research that has never before

or since been equaled by any

other writer about the basketry

of ally other people. I merely

MONO INDIAN’s ACORN CACHE, USUALLY ERECTED IN FRONT OF

THE CABIN DOOR

|

propose to conduct

the reader, in an easy

and chatty kind of

way, to several basket-making peoples

of California, that he

may see them at their

work, learn a few

characteristics of special kinds of weaving, and gain a little

deeper insight into

what basket-weaving

used to mean, and

still does, to some of

those who are engaged in it.

In the Yosemite

valley, even under

the very shadow of

Sentinel Rock and

within reach of the

music of the great

Yosemite falls, two or

three camps of basket-making Indians

may often be found.

And yet they are not

Yosemite Indians.

There is a small,

scattered remnant of

the once great and

powerful Yo-ham-i-ti

tribe still in existence,

but its members are generally to be

found near Cold springs and at Wawona, rather than in the world-famed

valley to which they have given their

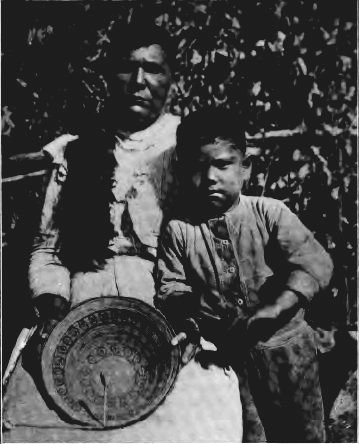

MERCED NOLASQUEZ OF AGUA CALIENTE, MOTHER OF THE PRESENT CAPITAN OF AGUA CALIENTE INDIANS

|

name. The Yosemite Indians of today are generally either Paiutis or

Monos, and both tribes are excellent

basket-makers.

A small but interesting collection of

baskets may be found in the valley,

at the photographic studio of Mr. J. T.

Boysen, and I have no doubt he will

gladly show it to visitors who proffer

a request to him.

Not far away from the foot of Yosemite falls is an Indian camp, and

there I found three acorn caches.

They are perched upon stilts and are

of rude basket-work, an opening being

left near the bottom through which

the store can easily be reached.

When I made my trip to the Monos,

before described in the pages of Sunset, I found there an acorn cache of

different construction. It was perched

on stilts, as were the Yosemite ones,

but these supported a rude platform

of crossed logs, on which the cache

proper rested. It is a pyramidal

structure and was erected in front of

the cottage door, so that it could be

constantly watched. Like the Yosemite caches, it is of rudely twined

twigs, but this, when full, was covered over with canvas, so as to protect it completely from the weather.

Further south than the Monos is

the Tule River reservation. Here I

found many expert weavers and discovered several interesting facts. We

speak of Tulare, Yokut, Paiuti, Fort

Tejon and Mono baskets as distinct

species of weave. I am inclined to

doubt whether any person can distinguish between them, unless he has

personally purchased from the weaver

and learned from her. to which tribe

she belongs. For here on the reservation are people of all these names.

The original stock that once inhabited

all this region, from the Fresno river

as far south as Fort Tejon, was the

Yokut. They were divided into a

number of clans, many of which are

named by Powers in his “Tribes of

California,” and several of which he

never knew. I found, among others,

the Yo-er-kal-is, Yo-el-man-is and Wi-chum-nas,

together with Paiutis.

Now, the intrusion of the Paiutis

(whose original habitat is Nevada)

into this region offers a most interesting

and fascinating field for meditation.

Why came they hither? They

STUDY OF A TYPICAL BASKET-MAKER OF CAHUILLA

|

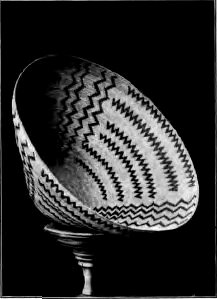

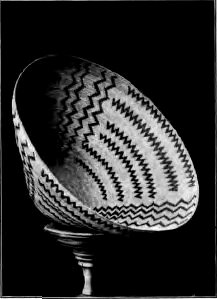

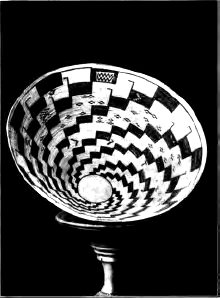

TULARE BASKET IN PLIMPTON COLLECTION, SAN DIEGO

The zigzag line represents lightning, the meanderings of a stream,

or the barbs of a Yucca palm.

|

themselves give the answer.

Living, as they did, on the

alkali plains of Nevada, subject to drought and consequent starvation, the struggle

for existence became too

great. Their hardships did

not prevent their multiplying

in great numbers, and soon

they were forced to “expand.” Whither should they

go? Eastward, where tribes

were similarly situated as

themselves, or westward,

where the game-haunted

summits and slopes of the

California mountains, the

fish-stocked streams of the

lower slopes, the fertile grass

and shrub-covered foothills

and valleys, and the herds

of deer and antelope that

roamed the plains assured

them a livelihood far superior

to any they had ever before

enjoyed? There were not

many passes, but with these

they were more or less familiar: Bloody canyon, Walker,

El Cajon. These afforded

the opportunity. Stealthily

they laid their plans, and

when time was ripe they forced their

way over the summits and completely

split the once powerful Yokut nation

in two. They took possession of

Kings river, Kern river, Kern lake

and Poso creek, and, though efforts

were now and again made to drive

them out, they found the land too

great a “land of promise,” a “land

flowing with milk and honey,” to

abdicate their joys. If they left, it

must be by force, and that the Yokuts could not apply with sufficient

convincement to be successful. Thus,

in a few years the singular spectacle

was found of this once great nation

split apart by the alien Paiutis, who,

from that day until they succumbed

to the vices taught them by the

whites, held securely to the territory

they had gained. The baskets of each

are almost alike in design and so

absolutely the same in weave, that no

person, however expert, could possibly tell which was Paiuti and which

Yokut.

ILLUSTRATED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE AUTHOR

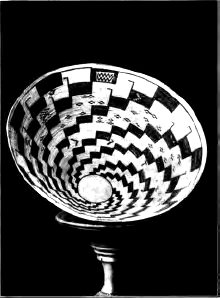

Three exquisitely woven baskets in

the Plimpton collection, San Diego,

(see illustrated title of this article)

reveal the various modes of presenting the human figure. The basket,

oval in shape, shown in an accompanying

picture, was made by a Wichumna of the Yokut tribe. She was

living in one of the upper reaches of

Kings river, in Kern county. Here

the figures are those of dancers, holding hands, some wearing feather kilts.

This undoubtedly represents a

“big dance”—something the weaver desired

to celebrate and keep in memory, as the kilted figures are possibly

those of shamans, many of whom were

present. The crosses were copied

from the pictured rocks of the locality, and, taken- in conjunction with

the great dance, the presence of so

many kilted shamans or medicine men,

and the explanation given that these

crosses represent battles, I assume

that this its the memorial basket made

by a woman who witnessed the dances

MONO MAIDEN BASKET-MAKER IN THE YOSEMITE VALLEY

|

held in honor of certain decisive victories won by her people.

Above the dancers is the diamond-back rattlesnake pattern, beautifully

woven. The basket to the left in the

picture is by a Tulare weaver, and

shows the general method followed by

this people to represent the human

figure. In the border above the figures is the rattlesnake pattern divided

into segments, and thus making a kind

of St. Andrew’s cross, which has led

some people to interpret the sign as

proof that these Indians have been

subject to Christian influences. This

is an error, at least so far as this design is concerned. It is a manifestation of the fact that makers do not

always slavishly adhere to any set

design, and that by and by there results a loss of the distinctively imitative pattern and the gain of a

conventionalized form that, by successive mutations, may lose all resemblance to the original.

One old weaver to whom I showed

PAIUTI EXPERT AT TULE RIVER RESERVATION

The basket designs of Yokut and Painti Indians are practically the same

|

this design informed me that the

rattlesnake pattern was originally

incorporated into baskets, by ancestors,

as a propitiatory offering to the snake.

‘Prayers were said asking immunity

from danger for themselves and families from the reptile’s deadly bite.

In the course of time the diamonds of

the design were cut in half and placed

upon the baskets in the form of a St.

Andrew’s cross. The identity of this

cross with the rattlesnake design

would be apparent to no one, and if

the inquirer were to ask of an Indian

what it meant, and he were to be told

that it was a prayer to the rattlesnake,

asking him not to bite the weaver, the

answer would seem to be far-fetched

and strange. Yet a study of the

growth of the design and the mutations through which it has passed,

renders its symbolic meaning clear.

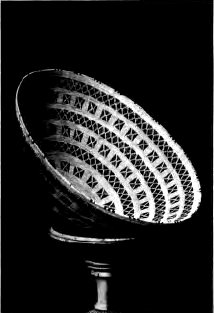

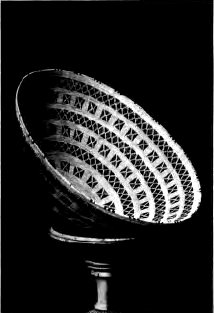

TULARE BASKET IN PLIMPTON COLLECTION, SAN DIEGO

Here the origin of the St. Andrew’s cross is believed to be shown

|

The basket to the right in this picture is an old Inyo county basket,

purchased in Lone Pine from a Paiuti

woman by Mr. A. W. de la Cour Carroll,

an enthusiastic basketry collector,

who has secured some choice specimens. It shows the oldest type of

human figure known to these Indians,

and offers a singular contrast to both

the other designs.

Another picture shows several fine

“Tulare” baskets in the Plimpton collection. In color, weave and design

they are equally delightful to the expert. In one the origin of the

St. Andrew’s cross is clearly and beautifully shown, as it is apparent to the

most casual observer that the single

crosses of the second, fourth and sixth

rotes of designs from the top are but

the diamonds of the first, third and

fifth rows cut in half at their points.

The design on another represents

watercourses, with quail, and the W-like design

in the upper part

of one of the watercourses

is said to represent a spring.

Another basket shown may

represent three different

things, and, as no interpretation was obtained from the

original weaver, the reader

may make his own choice.

With some weavers the zigzag line represents lightning,

with others a conventionalized representation of the

meandering of a stream, and

with still others the pointed

barbs of the yucca or Spanish

dagger.

At Cahuilla, made memorable by Helen Hunt Jackson

in her fascinating “Ramona,”

there are a number of skilled

basket-makers: Marie Los Angeles, Felipa Akwaka, Rosario Casero, Maria Antonia

and several others. Their

ware is not as fine as that of

the Yokuts, though it is

somewhat in the same style.

Maria Antonia beginning

work on a basket is shown

in one of the photographs.

The inner grass of the coil

is called “su-lim,” and is

akin to our broom corn in

appearance. The coil is made by wrapping with the outer husk of the stalk

of the squawweed and skunkweed,

and the root of the tule, the two

former being termed “se-e-let” and

the latter “se-el.”

The only colors used are black,

brown, yellow and white. The white,

yellow and brown are colors natural

to the growth and are neither bleached

nor dyed. The black is made by taking a potful of mud from the sulphur

springs that abound in the reservation

and boiling it, stirring the mud and

water together. As the mud settles

the liquid is poured off, and, while

hot, is used to color the splints. Two

or three “soakings” are necessary to

give the fast and perfect color. The

brown is the natural color of the tule

root. The outer coating is peeled off

into splints never longer than ten

inches, but generally nearer six or

seven. It is a common sight to find a

TULARE BASSET IN PLIMPTON COLLECTION

The design represents water courses with quail

|

number of these splints hung

up in the humble kishes,”

or tule or willow huts of the

Cahuillas.

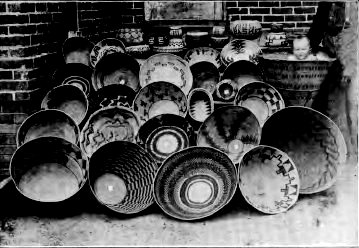

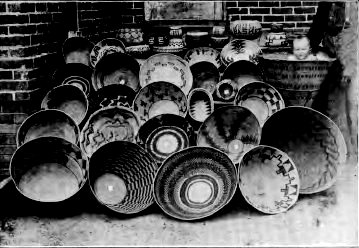

A number of baskets of

these people are here shown,

and some from other villages

of the vicinity. They are

mainly in the collection of

Dr. C. C. Wainright, the

physician of the Tule River

and Mission Indian Agency.

A few of the baskets are

mine. The one to the extreme right of the bottom

row in this picture was made

by Juana Apapos, at Saboba,

near San Jacinto, and yet it

represents mountains and

valleys — conventionalized,

of course—of the region

round about Cahuilla. The

mountain peaks are represented by the higher portion

of the design and the valleys

by the depressions. It will

be noticed that black splints

are worked into the valleys.

These represent the soil, and

the small white spot underneath the soil shows the

water sources— the springs.

Above the valleys are two large

black triangles, united. When I asked

Juana what these represented she was

a long time in answering. She was

afraid I would laugh at her, and, with

an Indian’s sensitiveness to ridicule,

she positively refused to tell me. But

when I finally satisfied her that I

would not laugh, she said they represented trees. When she began the

design she soon saw that they would

come out much too large, but she had

started and was resolved to finish

them as she had begun.

Human figures are seen in the basket to the left, in the bottom row, and

in the oval basket in the third row

from the bottom are conventionalized

arrow points. In the basket below

the one which bears the legend, ”1895 Basket,”

are flying geese, and in the

second basket from the left, in the top

row, is a representation of the tracks

of a worm. The second basket from

the left, in the second row from the

top, shows the rainbow, while the

second basket from the left, in the

bottom row, has the spider-web pattern

afterward to be referred to.

The conical carrying basket to the

right, in which Dr. Wainright’s little

boy insisted upon sitting while I made

the photograph, contains a design

that perfectly represents the poetic

conceptions of the Indian and her

methods of weaving them into her

basketry.

In another picture is reproduced an

interesting Cahuilla photograph. It

shows the Ka-wa-wohl or acorn mortar,

around the top of which a circular

piece of basketry is securely fastened

with pinon gum. This basketry acts

as a guard to keep the acorns from

flying out as the “ta-kish,” or

pounding stone, is brought down upon them.

It is laborious work, this whole process of making bread from acorns, for

everything has to be done without

any of the modern methods for saving

strength expenditure. Students of

the human face and hands will also

YOKUT WEAVER AND A FUTURE CHIEFTAIN

|

be much interested in those here

shown, especially the hands, for there

are characteristics in them that are

generally associated only with centuries of high breeding and culture.

Another Cahuilla weaver shown is

a keenly alert and intelligent woman,

Maria Los Angeles by name. She

lives in Durasno canyon — the canyon

of the peach — at Cahuilla, and makes

quite a number of fairly good baskets

each year.

At Agua Caliente, on Warner’s

ranch, San Diego county, are a number of good basket-makers. Their style

of weave, materials and colors used,

and general run of designs are similar

to those of Cahuilla, and it would be

impossible to determine at which

place a basket was made if one had

not seen it in the process of manufacture. Merced Nolasquez is the

mother of the present Governor or

Capitan of Agua Caliente, and she is

MARIA LUGO, POUNDING ACORNS AT CAHUILLA, SHOWING THE KA-KA-WOHL OR ACORN MORTAR

|

naturally an aristocrat and a leader.

She and her son both have a dignity

which would impress any one who

could see below the Indian exterior.

A short time ago a high dignitary of

one of the churches wrote a letter to

the press, stating that these people

were suffering for want of the necessaries of life. It might have done the

reverend bishop good had he seen the

indignation of this woman and her son

when they were told what had-been

said of them and their people. They

repudiated the idea that they or any

of the Indians of Southern California

needed help from the white man. All

they asked was that they be left alone

and given a fair chance, and they were

quite capable of caring for. themselves. The same things were said at

Cahuilla, where I went around and

visited every “kish” or house, in the

village. With the exception of three

sick and crippled persons, there was

not one who did not resent the imputation of incapacity to provide all that

was necessary for the proper sustentation

of life.

The design of Merced’s basket is

the spider-web pattern, a pattern

largely popular with the Hopi people

of northern Arizona, and found on

many of the baskets used for holding

the sacred meal in their snake dance,

which is now one of the best known

of all Indian ceremonials.

When I asked Merced for the meaning

of the of the design, she said that in the

long time ago her people lived where

there was little or no water. They

prayed constantly for rain, but before

their prayers were uttered they sought

to gain the favor of the Spider Mother,

who made all the clouds, and they

wove the representation of the spider

web in their baskets for that purpose.

When I told her that, prior to the

Hopi snake dance, the Antelope priest

goes, with sacred meal and bahos

(prayer sticks), to the shrine of the

Spider Woman and their prays and

sprinkles the sacret meal from one of

these baskets and deposits the bahos,

she said:

“Perhaps they (the Hopi) all same

as my people long ago.”

To attempt to describe the different

kinds of weaves in this article would

be impossible. In spite of the ridiculous

assertions sometimes made, that

there are only two styles of weave, I

must again affirm, as I have done elsewhere,

that he who imagines Indian

basketry is so simple and primitive an

art is far too ignorant to white upon

the subject. In my small book I have

let experts tell what they know about

it, and, as Dr. Hudson says of the

Pomas alone, they have nine kinds of

weave still in use and four that are

obsolete, and as many more kinds can

be found in the widely diverse basketry

of the southwest.

Another most interesting thing in

connection with basketry should not

be overlooked, and that is that the

materials used depend almost entirely

upon the natural growths of the countries

in which the various weavers

live. For instance the Pomas find a

beautifully colored and tough, durable

wrapping splint from the root of the

slough grass. The Cahuillas, on the

other hand, not having this particular

grass root, substitute the root of the

tule. In Arizona, however, the outer

husks of the various yuccas have to

answer for this same purpose. In

Japan the bamboo is used, in Maine

the sweetgrass, and so on. Hence

there is to be gained from the study

of Indian basketry a knowledge of

techno-geography that in itself is

highly instructive and interesting.

CAHUILLA BASKETS MAINLY FROM THE COLLECTION OF DR. C. C. WAINRIGHT AT

THE TULE RIVER AND MISSION INDIAN AGENCY

|

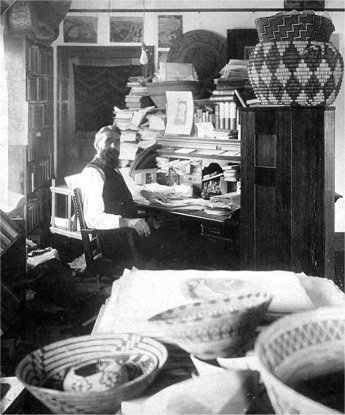

About the Author

Bibliographical Information

George Wharton James (1858-1923),

“Basket Makers,”

Sunset 8(1):2-14 (November 1901).

Illustrated. 28 cm.

In 1907 George Bryon Gordon acquired the

Fred S. Plimpton California basketry collection

for the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology,

Philadelphia.

Converted to HTML by Dan Anderson, October 2007,

from a microfilm copy at the California State Library

and a digital copy from University of Michigan.

These files may be used for any non-commercial purpose,

provided this notice is left intact.

—Dan Anderson, www.yosemite.ca.us

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/basketmakers/