[click to enlarge]

Benton Mills, on Merced River, at Bagby, foot of Hell’s Hollow.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Call of Gold > 23. Autobiography of John S. Diltz >

Next: 24. 1859 Mariposa • Contents • Previous: 22. First White Woman in Bear Valley

Captain John S. Diltz, one of the best miners of pioneer days, is speaking:

“When I was a boy, between ten and eleven years of age, my father died and I was the one of the family to support my mother. I had an uncle, my mother’s brother, Matt Stephenson, who sympathized and took an interest in her welfare and encouraged me.

“I had a spell of fever and ague for several years in Indiana and the doctors would pour the calomel down me. When I was a young stripling boy, I was reduced to a skeleton. My uncle came up from Georgia, where he had been mining for nearly ten years, to see his sister. He told me that if I did not get away from there immediately that I would soon be laid under the sod and that I must go with him, which advice I took.

“I arrived at the Georgia gold mines, June 15, 1842, and soon got fat and hearty. I lived and worked awhile with my uncle and acted as overseer of his negroes in the placer mines, where I learned to be a miner. I next bought a small lot and started on my own hook, and in 1848, went to see my mother and took money with me to pay for her home place, near Jeffersonville, Indiana.

“I then had to go back to Georgia and build a quartz mill and to work a vein that had been abandoned by parties some years before. It was rebellious ore and had not been properly treated. I got a man to help me and made well out of the mine.

“Mr. Moffat, of Brooklyn, New York, was out there and he and my uncle ran together for several years in their mineralogical and geological explorations. In 1848, General Taylor was elected President, and in 1849, my uncle was appointed Assayer in the Dahlonega, Georgia, Branch Mint and old Mr. Moffat was appointed to San Francisco. His Assay office was in a large fire-proof building on Commercial Street and in the time of the great fire, he was shut up in the building. It got so hot in there, he went down in the basement and threw himself on the ground and lay there till all the surrounding buildings were burned and when he got up, he found the great iron doors red hot and warped and drawn so out of shape that the air got in through the cracks and consequently saved the old man’s bacon. Later, he sold out to Kellog & Company and shipped most of his money home. He then interested some parties in his mine, got machinery and took it up to Mt. Ophir, where they spent money foolishly in putting up pulleys and ropes, with cars attached, to run ore from the top and the loaded car to draw up the empty one.

“In the latter part of 1851, I got ready to come out to Mr. Moffat. I leased my mine, early in 1852, and started for another land of gold. Distance, I guess, lent enchantment. There was really no cause for my leaving, when I had such a good start, but Mr. Williams, who had married my cousin and who was well-acquainted with Mr. Moffat, overpersuaded me and he left a wife and children, a fine farm and stock. I thought he had everything to make a man happy. We took a steamer at Charleston, South Carolina, and on the Isthmus, he got sick and died from the fever, on the ship, after leaving Panama. I was sick, at the same time, only escaping by a scratch and partially losing my hearing, but I got to San Francisco and up to Mt. Ophir.

“Mr. Moffat had sold out and was then on the San Joaquin River, building boats and diving bells to get the sands and gold from the river bed. I stayed with him during the summer of 1852 and I concentrated black sands for them, while Dr. Wooster was superintending the submarine work. I was there when Major Harvey shot and killed Major Savage and they brought the body in from Kings River. This affair blasted Mr. Moffat’s expectations as he had a promise of help from Major Savage. I went away and got into a good mine and soon had some money. Mr. Moffat’s works got smashed up with the first freshet. Provisions got scarce and we could not get flour for a dollar a pound and we lived on wild meat or barley and at times, the Indians would bring us some fish.

“Mr. Moffat was then all alone during these hard times and never would visit any person but me. I saw a man preparing to go down the river in a sail boat and I gave him $50 to bring up one hundred pounds of flour and money to pay for it, but there came up a steamer load before he got back and flour got down to $28 per barrel. As soon as the waters got down and teaming started on the road, I baked some bread, and with other provisions, got old Mr. Moffat into a wagon, with his bedding, and gave him some money, sent him to San Francisco, and his last words were that he was sorry that he and I had not been able to work a mine together and especially Mt. Ophir.

“In the winter of 1853-54, I placer mined on Mariposa Creek. I was there when Whitacre started the first paper in Mariposa, called the ‘Chronicle’, and when Cowan shot and killed a man named Newman, on Carson Creek, and they tried to lynch Cowan but he got out of the old log jail and got away.

“Major Daniels had erected a steam mill at Guadaloupe Flat, on Agua Fria Creek, in 1851. It was an old Mississippi boiler and engine, eighteen square stamps in six batteries or three stamps in a battery and had Hungarian bowls for amalgamators but no concentrators for sands and sulphurets, and all went into the creek. Yet they claimed to work sixteen to eighteen men. They cut all the timber that was anyways near and burned six cords a day under that old boiler.

“In the fall of 1854, Billy Snooks, who was mining at Guadaloupe Flat, adjoining Major Daniel’s claim, asked me to be his partner. I explored a day or two and found that the vein had been gouged by Mexicans, and the best of the ore, near the surface, taken away and ground on arastras. I pitched in and cut any kind of scrubby timber that I could find near at hand but I got some very good lumber sawed at Kavanaugh’s saw-mill in Mariposa. We constructed a mill, consisting of eight very heavy square stamps, four in a battery and a self feeder, which method I had learned in Georgia. For power, we built a thirty foot wheel to run by water, during the rainy season. In the meantime, my partner fell down a steep bank and was hurt so that he could not help me.

“When I got my mill ready to run by water, Christmas 1854, the creek was perfectly dry. They laughed and made all sorts of sport over me. I got two small mules and a small dump-wagon and hired a teamster to haul in several hundred tons of quartz to the mill. By the first of February, all room for ore was blocked up and the creek as dry as a chip. We managed to pay off our teamster and discharged him. Snooks had, by this time, got able to do the cooking.

“The rain set in about the fourteenth of February and on the fifteenth, I started the first self-feeding quartz mill in California. I never saw anything work so pretty as that did. I was the only person about the mill, and when there was about twelve tons of ore in the boxes or hoppers, I could go away and leave the mill running until the whole box of ore was gone under the stamps. The free gold was saved, in the mercury trough, which was locked up, and the sulphurets concentrated, which I cleaned out and put into a box and threw salt water on and ground in an arastra. Merely, for a test, I hauled and milled a lot of the Mexican refuse.

“I let the good quartz that was hauled lie until I first put through the low grade ores. I harnessed up the little team, and doing all the hauling and driving myself, hauled in eight loads of miner’s tailings and ground piles of float rock which was then lying scattered over the placer sluice washings. After I had done a full day’s work by hauling and dumping into the feed box, I laid down by myself and slept. At regular hours, I would get up, tallow the gudgeons and cams, wash blankets, unlock, open and look into the amalgam boxes, regulate the water on the feeders and in the batteries, draw off the sulphurets from the concentrator. I would then go back to bed and sleep for two hours, then get up and go through the same operations.”

“In the morning after all this, I would take a pan full of sands, from below the concentrator to see if it had done its duty. I put through two hundred tons a month when there was a full head of water or say thirty or forty inches. The steam mill was idle a good deal for repairs and quartz and scarcely ever put through more than one hundred and fifty tons per month. By April, our water got down to eighteen or twenty inches, or say half a head, and ran one battery. In May, we shut down the mill and got out quartz in the summer and fall. The result was that we ran way ahead on low-grade ore, say $3 to $5 rock, while the steam mill ran far in the rear on $10 ore.

“I was mining here till long after Fremont got his patent. Then Snooks and I bought into the Morris Goodman & Company mine on Whitlock Creek, where they had six arastras running by a forty foot overshot water wheel. I removed five of the arastras and had only one left to grind the sulphurets with. I put up ten stamps in two batteries and a self-feeder exactly like our Guadaloupe mill and the first winter could not get ore fast enough from the Spencer vein to keep the mill running. This was the winter of 1856-57.

“The Whitlock mine was lying idle then and was claimed by Richard Foisy. It had been worked some years previously by Dr. Bunnell and others. I explored and prospected and found the vein only cropped out in three or four places on the surface. There were only two or three holes sunk a few feet deep on the whole vein, which I could trace north and south for twelve hundred feet. I paid Foisy for his claim on it and put two men sinking a shaft about midway.

“The vein at this point averaged four and a half feet in the shaft, which was inclined and dipping under a hanging wall on an angle of say forty-five degrees east. I sank the shaft one hundred and fifteen feet deep but did not get as low as spring water. While this was going on, I made the wagon road from the mill two miles from the mine. There was four hundred and fifty tons of rock hauled over the new road before it was completed and before the shaft was down. One large block of quartz, which weighed several hundred pounds, which I took to the Stockton Fair, in the Fall of 1857, drew the first prize and afterwards assayed net $333 at the refining works.

“The winter of 1857-58 was a dry year and we only milled some of the best ore on the old water mill. We bought the old Bunnell machinery and I went to San Francisco for a new boiler and twelve stamps. The engine which was about a twenty horsepower ran the stamps and a nine-foot arastra and milled one hundred tons a week. While the mill was being built, we were having another shaft sunk on the Whitlock mine and one on the Spencer.

“I put through the first one hundred tons which yielded $3000, and the next $2500 and the third $2000. One week we ran the poorest ore that we knew of, it was the outcroppings of the vein and cost nothing to get out. It milled about $6 per ton. I stayed there until we put through the mill one thousand tons, which milled in the neighborhood of $15,000 and I concentrated about two tons of sulphurets, which with my boiling salt water, I amalgamated and obtained $600.

“I then proposed to my partners that if they would carry on the work and bear expenses, I would take the tailings and work them for my part. This caused a fuss in the family and I sold out my interest to Snooks and went back to Guadaloupe to take my chances with Fremont.

“The Whitlock men, after I left, employed forty men, whereas I had only ten to get ore out and to haul for a twelve-stamp mill. They got a man to come with chemicals, put up pans and to treat the sulphurets. They altered my mill from a self-feeder to feed with a shovel and to crush dry and the next thing that followed was that they made a disgraceful failure and gave everything a bad name.

“It was near Christmas, 1860, when Trenor W. Park, who was then manager of the Fremont Estate, and Colonel James, asked me to go to Mt. Ophir and show them how to run arastras, which I did. While at Mt. Ophir, three mills were worked, running on Princeton rock for two years and at last, we put through the mills the old dump left by the English claimants of the Mt. Ophir mine and they paid nearly an ounce to the ton.”

[click to enlarge] Benton Mills, on Merced River, at Bagby, foot of Hell’s Hollow. |

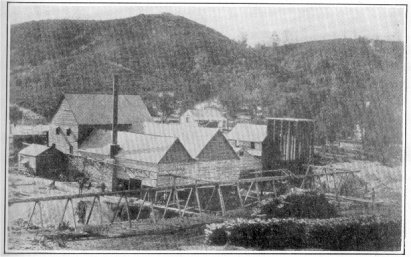

[click to enlarge] Mt. Ophir mine and mill. The Moffat Mint was close by. |

Next: 24. 1859 Mariposa • Contents • Previous: 22. First White Woman in Bear Valley

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/call_of_gold/john_diltz.html