[click to enlarge]

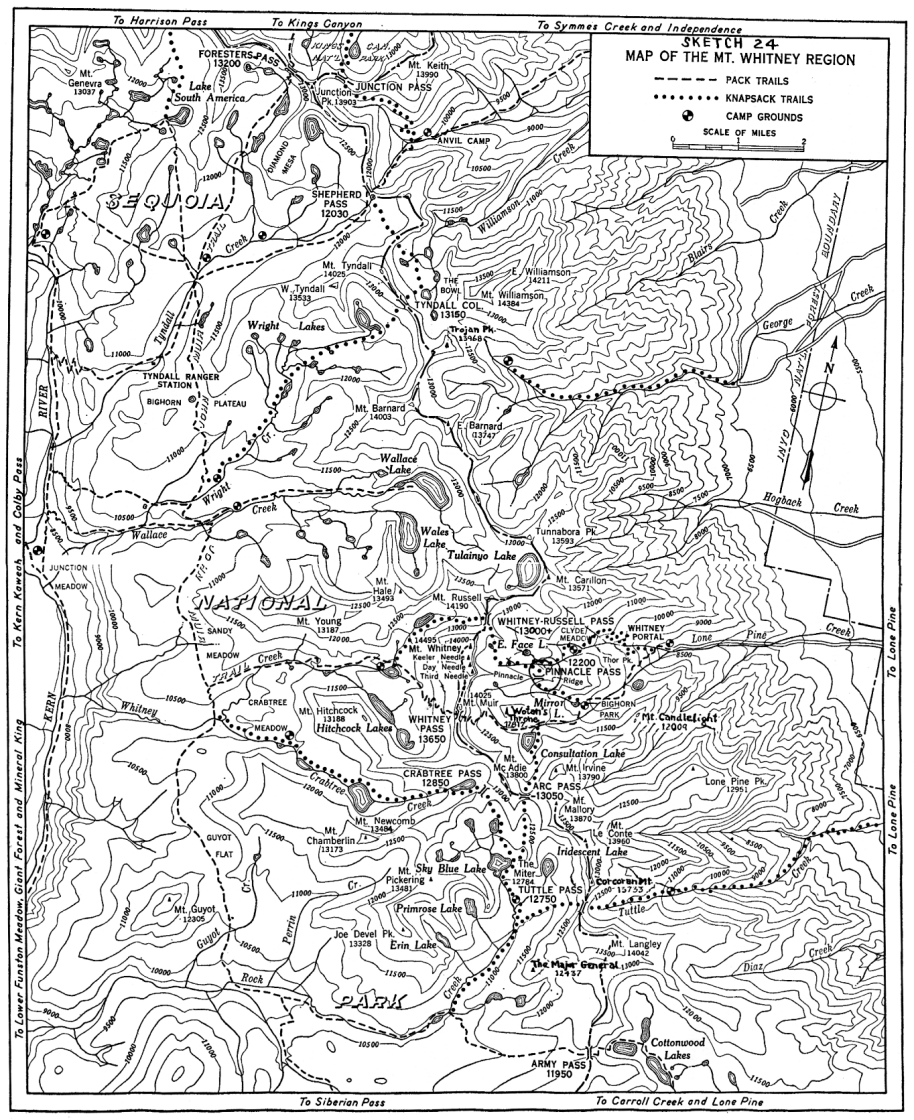

Sketch 24. Map of the Mt. Whitney Region.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Climber’s Guide to the High Sierra > The Whitney Region >

Next: Kaweahs & Great Western Divide • Contents • Previous: Kings-Kern Divide

THE WHITNEY REGION, that portion of the crest of the Sierra Nevada lying between Shepherd Pass and Army Pass, is a spectacular display of mountain sculpture. Rising west of Lone Pine, in Owens Valley, and following the northeast border of Sequoia National Park, this jagged thirteen-mile escarpment includes seven of California’s fourteen peaks exceeding 14,000 feet in elevation: Mounts Tyndall, Barnard, Williamson, Russell, Muir, Langley, and the culminating summit, 14,495-foot Mount Whitney, highest peak in the United States excluding Alaska. The 10,000-foot scarp of the Mount Whitney fault block forms impressive eastern precipices. Deep glacier-cut canyons, glacial cirques plucked out among the peaks, moraine deposits in the valleys, sharp ridges, myriad glacial lakes, alpine trails and passes, beautiful timberline campsites—these provide a wilderness of variety for the climber. Indeed, one of the finest rock climbing areas in the Sierra is concentrated in the six miles between Mount Russell and Mount Langley.

In 1864, members of a California State Geological Survey party, Clarence King and Richard Cotter, viewed the region from the north and gave to the highest point the name of their chief, Whitney. Years later, after two unsuccessful attempts, King reached the summit, only to learn that he had been preceded a few weeks by several parties from Owens Valley. A. H. Johnson, C. D. Begole, and John Lucas had, on August 18, 1873, been the first to reach the top. During the years following, the summit rocks have known the tread of countless climbers, singly, in groups, in mass ascents. They have been visited by world travelers, by trail builders, by survey parties. The trail to the summit was completed in 1904, and a stone shelter was erected on the peak in 1909.

Mount Whitney has naturally received the greatest share of attention, both from climbers and from historians. Little, therefore, is known of the early history of the other 14,000-foot peaks of the region, except for Mount Tyndall. This first came to attention in 1864 when King and Cotter made their famous ascent so dramatically described in King’s Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada. Of recent years, dating specifically from the introduction of modern roped climbing on the East Face of Mount Whitney in 1931, the mountaineering approach to the region has been somewhat altered.

A mountain mass of fault-block origin usually possesses a precipitous face contrasting with a gentle approach. This characteristic is exhibited to a striking degree in the region surrounding Mount Whitney, for the general contour rises gently from the west, only to break off in huge cliffs toward Owens Valley on the east. Accordingly, the majority of the difficult climbs are found east of the crest. For details of topography refer to the Mount Whitney and Olancha quadrangles of the United States Geological Survey map, or the Sequoia Kings Canyon National Parks topographic map. A sketch map (Sketch 24) shows knapsack routes and some local names not on the USGS maps.

In general, the most exposed faces are quite firm; eternal vigilance, however, must be exercised to avoid mishap. The general dependability of the cliffs does not extend to the chutes. Some members of an inexpert or careless party may readily find themselves subjected to a deadly barrage, usually caused by the climbers above. In addition, rockfalls and snow avalanches occur from natural causes, and any leader conducting his party without due regard for this contingency is guilty of negligence or poor judgment. Unsettled weather, accompanied by hail storms, often occurs during the summer, and will, of course, affect climbing conditions. Climbers are also reminded that many of the routes involve a length of time and altitude well in excess of that normally encountered in the Sierra. The Whitney Region contains no glaciers, and ice equipment is unnecessary in late summer and fall. One must remember that

[click to enlarge] Sketch 24. Map of the Mt. Whitney Region. |

The Whitney Region is most accessible by Inyo National Forest trails from the east; here the grandeur of the range is an inspiring sight, the most lofty summits towering well over 10,000 feet above Owens Valley.

From Independence. From U.S. 395 at the south end of Independence, drive to the Symmes Creek road end (5,900). Follow the arduous trail which starts up Symmes Creek, and leads over to and up Shepherd Creek, where one can camp at timberline (10,400) below Shepherd Pass (12,030). Mounts Williamson and Tyndall can be climbed from the pass.

From Manzanar. Take a dirt road just north of Manzanar, and follow to the second road branching right. This passes through a gate, and just beyond take the right-hand road. Drive to a level spot below a very steep hill (impractical for standard cars). Walk one-half mile to the end of road. Hike up a faint trail on the south side of George Creek to a waterfall about half-way to timberline. Cross below the waterfall and continue up the north side. Just below timberline, the stream forks. If Williamson is the objective, ascend north (right) branch to timberline camp. If Barnard is to be climbed, go up south (left) fork to camp just below a small lake.

From Lone Pine. Drive up Lone Pine Creek to Whitney Portal (8,350), where a Forest Service campground is maintained. The Mount Whitney horse trail leads up the Middle Fork to Bighorn Park (10,355), Mirror Lake (10,650), and continues to the summit of Mount Whitney by way of Whitney Pass (13,600+).* The John Muir Trail junction is near the pass. Most convenient bases for the East Face and Mountaineer’s routes upon Mount Whitney are at East Face Lake (12,850), or on the North Fork of Lone Pine Creek to the southeast and at a slightly lower elevation. These sites lack firewood. Some climbers prefer to camp at Mirror Lake, which is supplied with firewood, cross Pinnacle Pass, climb Whitney’s East Face, and return via the horse trail in a long day.

* Do not confuse with pass (B.M. 13,335) formerly crossed by trail.

East Face Lake or the upper North Fork campsites may be reached from Mirror Lake via Pinnacle Pass, or by climbing directly up the North Fork. The first route possesses the advantage of an excellent trail as far as Mirror Lake, but involves a subsequent trailless climb of 1,600 feet and a steep descent of 300 feet. The North Fork route is more direct and primitive, but occasionally obscure. Ascend the foot trail, which starts at the highest point of the road. Where the trail joins the horse trail, turn left for Mirror Lake or right for the North Fork near-by.

North Fork Route: Proceed up the south side of the stream for approximately one-half mile after leaving the trail. Beyond a large triangular rock, cross the fork and ascend a steep, narrow slope. This is the first break in the cliffs, and is marked by large pines. After approximately loo feet of climbing, a narrow ledge running downstream will be found. Follow this up and to the right almost to the end, where it will be possible to turn left and follow another shelf upstream. This way (Ebers-bacher Ledges) replaces the route south of the stream. Remain on the north side of the fork to Clyde Meadow, a lovely bowl graced with a tarn amid foxtail pines. Beyond the meadow, recross to the south side of the main stream and ascend large talus blocks. At the crest of the slope, recross to the north side and ascend to a point about three-quarters of a mile east of the great walls of Whitney. Gravel will provide reasonably comfortable campsites.

If it is desired to camp at East Face Lake, proceed onward to a point just beyond a stream coming from the right (N). Turn right and ascend the steep but rather firm rocks (less tiring than the talus farther upstream). East Face Lake is a short distance beyond the crest.

From Cottonwood Creek. Drive up the Lone Pine-Carroll Creek road and ascend Cottonwood Creek via trail. Numerous campsites will be found in the vicinity of Cottonwood Lakes. Mount Langley is easily climbed from this trail, which leads over Army Pass.

Other Approaches. Entry into the Region from Kings Canyon National Park is gained via Foresters Pass (John Muir Trail), or over Colby Pass and down the Kern-Kaweah. From the Giant Forest, climb via the High Sierra Trail over Kaweah Gap and across the Big Arroyo. A long pack-in can be made up the Kern River from the south. The accompanying map should be studied for location of higher campsites.

The Whitney Region is crossed by three passes having stock trails. These are Shepherd and Army Passes, bounding the region to the north and south, and Whitney Pass, south of Mount Muir. Other passes are undeveloped, suitable primarily for knapsack parties.

Tyndall Col (13,100+). Class 1. Connects the Bowl with Wright Creek.

Whitney-Russell Pass (13,300+). Class 1. The notch provides convenient passage between the North Fork of Lone Pine Creek and Whitney Creek. East to west: Ascend talus northwest of East Face Lake, and climb into the notch at the corner of the wall north of lake. West to east: Front the bowl at the head of Whitney Creek, climb talus, keeping to right to higher (S) of two notches through headwall. The lower notch is too steep on the east side to be feasible.

Arc Pass (13,000+). Class 1. This saddle offers a direct route between Consultation Lake, in the Middle Fork of Lone Pine Creek, and upper Rock Creek. North to south: Pass the lake on the east and climb the talus to the south, keeping high up to the left until it is convenient to follow a ledge back to the right into the pass. South to north: From Sky Blue Lake, ascend talus to the northeast into a small cirque; thence directly north into the pass.

Tuttle Pass (12,700+). Class 1. This route involves a long trek along the south fork of Tuttle Creek, and is recommended only for sturdy knapsackers.

Crabtree Pass (12,800+). Class 1. A convenient link between Crabtree Creek and Rock Creek recess.

Pinnacle Pass (12,200). Class 2. South to north: Pass north of Mirror Lake and ascend a broad, sloping canyon to northwest, keeping near the base of cliffs to north. After three-quarters of a mile, ledges on the right lead up to the pass, 1,600 feet above Mirror Lake, just right of a prominent pinnacle visible from Mirror Lake. The first part of the descent, eastward, is moderately difficult rock work; below, descend diagonally west. The lower portion and the basin floor are composed of very rough talus. Proceed diagonally toward Mount Whitney to the right side of canyon. Camp on sheltered gravel beds, or ascend to the East Face Lake plateau by going to a gully a short distance beyond the point where a stream comes down the right slope. North to south: From the North Fork canyon, ascend talus at the first place where it rises appreciably against the south wall. At the high point of the talus (300 feet above the stream), follow ledges right and upward into the pass.

Mount Tyndall (14,025)

Route 1. North face. Class 3. First ascent July 6, 1864, by Clarence King and Richard Cotter. From a point between Shepherd Pass and the saddle leading to the Bowl, ascend the rib in the middle of the face (or the gully to its right) over granite slabs, to the arÍte. Proceed east among the gendarmes to the summit.

Route 2. Northwest ridge. Class 2. Leaving the Shepherd Pass trail, climb the ridge at the junction of north and northwest faces. Ascend to the arÍte of Route 1 and follow it to the summit. Variations: Climb any gully to the south of the northwest ridge, traverse the south face of the north peak 100 feet below its crest, and ascend to the arÍte, thence to the summit.

Route 3. Southwest slopes. Class 2. First descent July 6, 1864, by Clarence King and Richard Cotter. Mount talus above the highest lake on Wright Creek.

Route 4. East face. Class 4. First ascent August 13, 1935, by William F. Loomis and Marjory Farquhar. Climb the first prominent open chute on the east face of the north ridge. The principal difficulty is entering

the chute. Route 5. Southeast ridge. Class 4. First ascent August is, 1939, by Ted Waller and Fritz Lippmann. The ascent from the east of the southeast wall of the third large chute southeast “of Tyndall involves 500 feet of class 4 climbing. The rest of the route follows the nivated southwest slope of the ridge to the top.

West Peak of Tyndall (13,533). Class 2. First ascent unrecorded. The oddly sculptured northwest face offers varied scrambles of similar difficulty, all on excellent granite.

Photographs: SCB, 1894, pl. 11; 1933, 30 (east face).

Point 12,350 (Tawny Point) (N of Bighorn Plateau)

First ascent July 12, 1946, by A. J. Reyman; class 1 from the south. Class 1 and 2 from the north. Minimum class 3 up a steep gravel and rock couloir on the west side, meeting ridge one-half mile north of summit.

Mount Williamson (14,384)

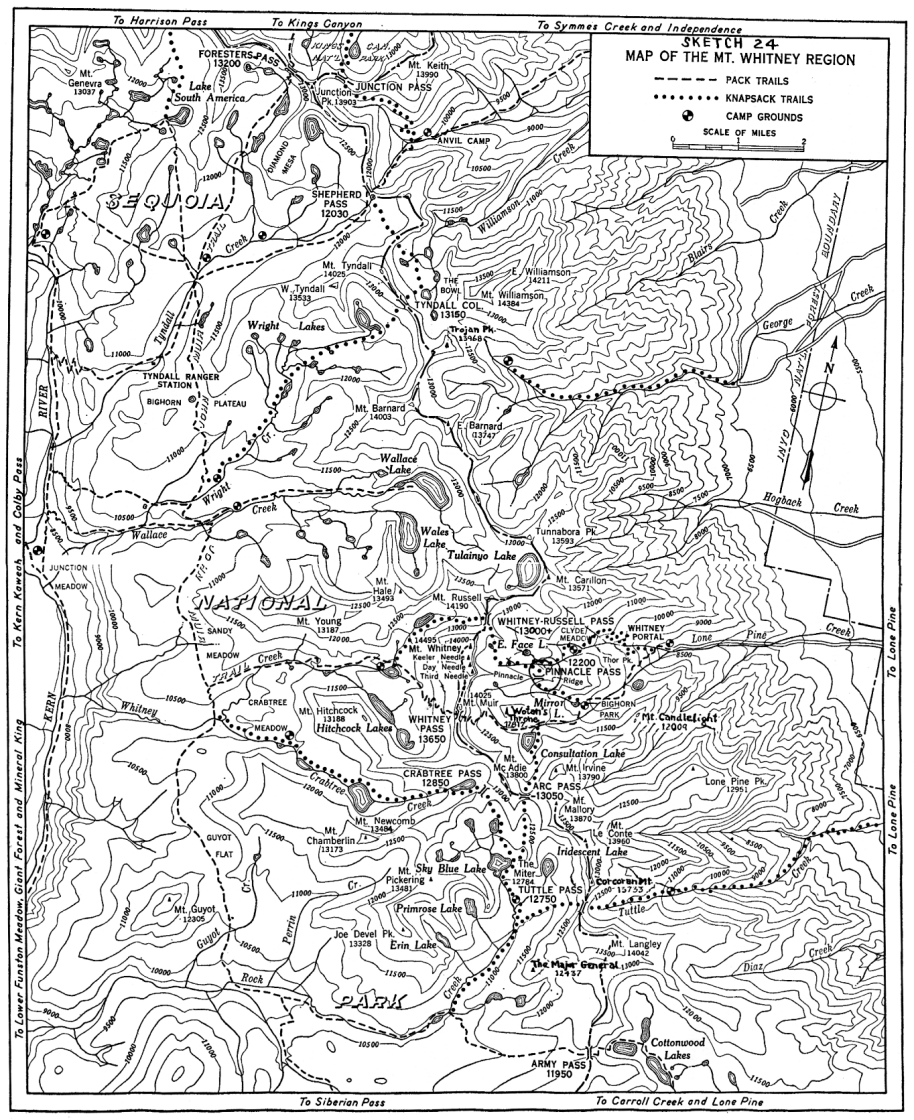

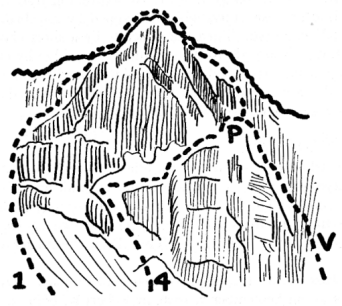

Standing apart from the crest, Williamson offers one of the finest views of the eastern escarpment, and is one of the most imposing peaks, to be seen from Owens Valley. Although first described as “an inaccessible cluster of granite needles,” the summit has now been reached by, many routes. The mountain is so complex that it is easy to get off the, route and into difficulty. Accordingly it is well to have a rope available, even though the actual climbing problem on most of the routes is, moderate in degree. Williamson from the northwest, with marked routes, is shown on Sketch 25.

[click to enlarge] Sketch 25. Mount Williamson from the northwest. |

| 2 | Route 2. | R | Red talus |

| B | Black stains on rock | NNN | Northwest buttress |

| S | Summit | NF | North face (lower

portion hidden by northwest buttress) |

| SL | Small lake | ||

| V | Variation on Route 2. |

Route 1. Southeast ridge from George Creek. Class 2. First ascent in 1884 by W. L. Hunter and C. Mulholland. A nine-hour, almost trailless climb up George Creek brings one to a timberline campsite (about 11,500) on the north fork of the creek. From here ascend north-northeast to the gradual slope of the southeast ridge, following this to the base of the steeper slope. Here it is possible to cross the east slope past a small lake and then go diagonally upwards; but “much the easier climb is to keep on . . . the backbone of the ridge . . . There is not very much difficulty in either direction.” (A. W. Carroll)

Route 2. From the Bowl. Class 3. First ascent by this approach was in July 1896 by Professor Bolton Coit Brown and Mrs. Lucy Brown. The 1,800-foot west face of Williamson has provided varied routes to the summit, and, to less experienced climbers, many cul-de-sacs. After approaching from Shepherd Pass, follow the top of the low ridge which separates two lakes in the floor of the Bowl. Proceed along the ridge, avoiding cliff by passing to the right. After passing the rise in the center of the basin, and beyond the second of two lakes to the right of the ridge, move straight toward the summit of Williamson. Ascend to the right on talus toward black marks on rock caused by snow water, and enter the chute above. This is a double chute separated at its mouth by a lower buttress, which resembles an inverted shield with a rectangular column superimposed on top of it. Ascend the right branch of this double chute, which soon branches above; continue up the left branch. Near the top avoid a broad slope to the left. Climb a chimney and emerge on top of a high plateau which slopes gently toward the summit.

Variations. Another, perhaps more frequently used, route lies well to the south. From the Bowl climb up red talus. Ascend the southernmost of abundantly scree-filled chutes, keeping to firmer rock along either wall, to the notch in the southwest ridge. Cross into an open chute in the upper south face, and climb ledges in zigzag route marked with ducks to the nivated summit slope. Several other variations have been worked out by Norman Clyde and others, sometimes unintentionally. The southwest arÍte may be followed to the summit, but this is almost class 4. The west face chutes north of Route 2 have been used frequently, but involve much more scree and route-finding. The abundant scree in these chutes can simplify the descent—provided one chooses the correct chute.

Route 3. Northeast ridge. Class 4. First ascent 1925, by Homer D. Erwin. This involves an arduous trailless approach up Williamson Creek. From timberline ascend a chute heading on the nivated slope on the northeast ridge of Williamson and follow the ridge over Peak 14,150 and Peak 14,211 (see East Peak of Williamson) to summit. Norman Clyde has followed the northeast ridge from Owens Valley—an 8,000-foot, waterless climb from the mouth of the Shepherd Creek gorge.

East Peak of Williamson (14,211). Class 4. First ascent by Leroy Jeffers. From the summit of Williamson descend northeast along the summit plateau; drop 200 feet to the notch below the plateau by traversing diagonally down the southeast side of the notch; ascend a chute to the crest of the sharp east peak arÍte; and drop 100 feet down the opposite side, whence a minimum class 4 pitch leads to the summit. Variations of this route are possible, the purpose of all of them being to avoid following the spectacular arÍte itself. The same applies to the ascent of Peak 14,150 to the northeast.

Photographs: SCB, 1904, plate 10 (from Owens Valley); 1910, plate 38 (from south).

Trojan Peak (13,968)

Route 1. Minimum class 3. First ascent June 26, 1926, by Norman Clyde, via west side.

Route 2. Maximum class 2, by north ridge from saddle south of Williamson.

Route 3. Class 2, from south.

Mount Barnard (14,003)

Class 1. First ascent, September 25, 1892, by John and William Hunter and C. Mulholland. This is a high granitic plateau rising from the south. The east summit (13,747) lies at the crest of the great eastern ramparts, which form an impressive 2,200-foot cliff. Mount Barnard can be easily ascended from Wright or Wallace Creeks, via the southwest ridge or the south slopes. The northwest slope and the north ridge offer convenient class 2 routes to the summit, and involve less scree. From the northeast an ascent may be made by a broad couloir above George Creek to the wide plateau. Climb class 1 talus slope to summit.

Peak 12,393, one and one-half miles west of Barnard, is class 1 via the southwest ridge.

Tunnabora Peak (13,593)

First ascent August 1905 by George R. Davis. Class 2 by the south slope from the headwaters of Wallace Creek.

Point 13,008, three-quarters mile north, is class 1 from Tunnabora.

Mount Carillon (13,571)

Class 2. This peak lies northeast of Mount Russell and one-third mile southeast of Tulainyo Lake. First ascent 1925, by Norman Clyde.

Mount Russell (14,190)

This peak presents a formidable appearance from almost any direction, and was one of the last of the major Sierran peaks to be climbed. The south wall is deeply fluted, consisting of four buttresses separated by deep couloirs. The outer ribs rise to nearly identical heights, making the summit a twin-horned arÍte. The north face is more regular, being cut by a series of horizontal ledges with steep smooth rises. The west summit is slightly higher than the east peak.

Route 1. East arÍte. Class 3. First ascent June 24, 1926, by Norman Clyde. From Tulainyo Lake, ascend the 500-foot wall to the south. Continue along a ledge on the north side under the crest of the arÍte, to summit of east horn (SCB, 1927, 382).

Route 2. North arÍte. Class 3. First descent June 24, 1926, by Norman Clyde. From the moraine bench just west of Tulainyo Lake, follow up the rib that leads into the north arÍte. Difficulties of the arÍte can be turned by keeping to right along ends of north face ledges.

Route 3. West arÍte. Minimum class 3. First descent July 1927 by Norman Clyde.

Route 4. Southwest face-west arÍte. Class 4. First descent July 1932 by Jules Eichorn, Glen Dawson, Walter Brem and Hans Leschke. From near the head of Whitney Creek, climb the narrow couloir just left of the buttress that rises sheer to the summit of the west horn. This couloir heads on the west arÍte; proceed thence by Route 3 to summit.

Route 5. South face-west chute. Class 3. First ascent July 1932 by Jules Eichorn, Glen Dawson, Walter Brem and Hans Leschke. From the head of Whitney Creek, or Whitney-Russell Pass, follow up the talus into wide chute occupying the center of the south face. Halfway up, the chute divides. Take the left (W) branch to near the end, whence ascend the right wall. Attain the arÍte, which terminates in the summit ridge just east of the west horn.

Route 6. South face-east chute. First ascent was made in 1928 by A. E. Gunther. From the branch in the chute of Route 5, continue up the right (E) couloir to the headwall. There are three variations from here: Gunther variation. Class 3. Climb the second chimney right (S) of the headwall to the crest of southeast arÍte, thence on to east side of arÍte and up blocks to summit of east horn. Chimney variation. Class 4. First ascent July 29, 1932, by James Wright. Climb the first chimney on the right (at corner), passing over loose overhang near top, to a shelf on the east face of the southeast arÍte, thence by Gunther variation. Face variation. Class 3. First ascent August 7, 1931, by Howard Sloan, Frank Noel, and William Murray. Climb the headwall by a ledge leading diagonally up the face to the left, ending at midpoint of the summit arÍte.

Route 7. Southeast face-east arÍte. Class 3. First ascent June 19, 1927, by Homer D. Erwin and Fred Lueders, Jr. From Clyde Meadow, go up the right (N) canyon of the North Fork of Lone Pine Creek. Near the head, a long talus slope leads east into a short but prominent chimney, which ends at a high mesa. Cross the plateau westerly to the east arÍte of Russell proper. From this point, the way is a variation of Route 1..

Photographs: SCB, 1927, 384 (from north, and west peak); 1928, plate 31 (from northeast).

Point 13,938. This peak rises just west of Mount Russell. First ascent June 27, 1926, by Norman Clyde. A class 2 traverse from Mount Russell.

Mount Hale (13,493)

Class 1. First ascent July 24, 1934, by J. H. and Mildred Czock via the south slopes.

Peak 12,808 (W of Wales Lake)

Class 2. First ascent September 5, 1935, by Chester Versteeg via the north ridge, from northwest.

Mount Young (13,187)

This peak is a long, rounded granite mass with a sheer north wall broken by avalanche chutes. An excellent view is obtained of the Whitney crest, the Kaweahs, the Great Western Divide, and the Kings-Kern Divide.

South slopes. Class 1. First ascent September 7, 1881, by Frederick Wales, William Wallace and J. Wright. Ascend from Crabtree Creek into the low saddle visible from the trail. Proceed to the summit over talus. Peak 12,820, five-eighths mile west, is minimum class 2 from the south.

Mount Whitney (14,495)

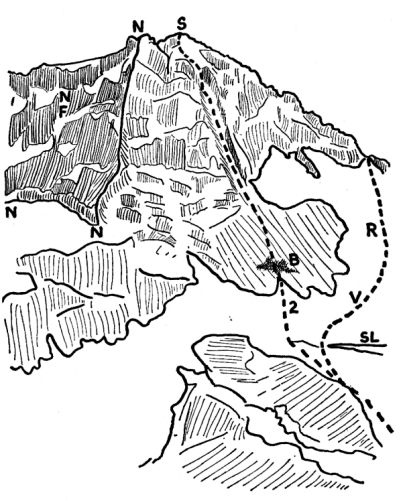

This peak provides an exceptionally wide range of climbing difficulty. One route is a horseback trail (Route 1, class 1), and entails nothing more than time and stamina. Scrambles, difficult to various degrees, may be made from the west and north (Routes 2 and 3). Block climbing and couloir scrambling are found on the Mountaineer’s Route (Route 4). Hardy and thoroughly experienced rock climbers can attack difficult and exposed routes up the East Face (Routes 5 and 6) and from the southeast (Route 7). The accompanying Sketch 26 shows East Face routes.

References: SCB, 1935, 81; 1936, 64; 1937, r; 1947, 75.

Photographs: SCB, 1894, plate 14 (from west); 1904, plate 13 (from west); 1904, plate 18 (East Face cliffs); 1909, plate 13 (down East Face); 1910, plate 37 (East Face); 1928, plate 30 (from north); 1937, plates 5, 6 (aerial) and 21 (crest trail); 1938, plate 40 (climbing); 1947, opposite 86, 87 (summit). American Alpine Journal, 1931, 416 (East Face). Sierra Nevada: The John Muir Trail. By Ansel Adams, 1938, plate 43 (Day and Keeler needles, East Face).

Route 1. The trail. Class 1. The path leaves the Whitney Pass trail about 300 yards from the pass on the west side of the crest. The way swings high on the west slope of the pinnacles, skirting the notches that give impressive views down the great eastern precipices. The final peak is surmounted from the southwest. Trail distance from the roadhead to the summit is thirteen miles.

Route 2. West slopes. Class 2. First ascent August 18, 1873, by A. H. Johnson, C. P. Begole and John Lucas. Leave the lower lake in the glacial basin at the west foot of the mountain. Climb steep talus and pass through any of the numerous chutes. Then proceed directly to the summit.

Route 3. North slopes. Class 2. From near the head of Whitney Creek, or from Whitney-Russell Pass, climb west over talus and large blocks. Keeping well under the wall of the north arÍte, ascend into any of the shallow chutes leading to a 50-foot wall of broken blocks. Pass through the wall and climb directly to summit. Note: Avoid the lower portion of the west half of the north face, for it is covered by steep, smooth glacial slabs, involving class 4 climbing.

Route 4 (Mountaineer’s Route). Northeast side. Class 2. First ascent generally credited to John Muir on October 21, 1873. A large couloir separates the north arÍte from the great East Buttress. This couloir leads directly from East Face Lake to a notch, the junction of the north arÍte with the main massif. From the junction, go left directly up 400 or 500 feet of steep large blocks (often icy) to a large cairn on the crest. The summit is 200 yards southeast.

[click to enlarge] Sketch 26. East face of Mount Whitney. |

| 1 | First Tower | SW | Summit of Whitney |

| 2 | Second Tower | M | Mountaineer’s Route |

| T | Tower Traverse | S | Start of southeast face

route |

| W | Washboard | ||

| F | Fresh Air Traverse | G | Gendarme |

| K | Portion of Keeler Needle | C | Whitney-Keeler Couloir |

| P | Peewee |

Route 5. East buttress. Class 4, with one class 5 pitch. First ascent September 5, 1937, by Robert K. Brinton, Glen Dawson, Richard Jones, Howard Koster and Muir Dawson. From East Face Lake, climb the talus and ledge to the left of Route 4 for 500 feet, reaching a notch between the First Tower and Second Tower on the face of the east buttress. Rope here and work right, up the face of the Second Tower. Turn it to the right 15 feet below its summit, thus gaining the second notch. On the first pitch above the notch, two pitons are needed for safety. Above this point, the route roughly follows the arÍte of the east buttress to a point below the “Peewee,” a huge, precariously-placed block of granite over halfway up the buttress. Climb past the right side of the block. Ascend directly ahead, or swing to right, up to summit blocks (SCB, 1938, 105, 106).

Route 6. East face route. Class 4, with two class 5 pitches, or one class 5 and one class 6 pitch. First ascent August 16, 1931, by Robert L. M. Underhill, Glen Dawson, Jules Eichorn and Norman Clyde. From East Face Lake follow Route 5 to notch behind First Tower. Rope up for the exposed “Tower Traverse,” class 4 (first ascent August 17, 1934, by Jules Eichorn and Marjory Bridge [Farquhar] ). Traverse left (S) face of Second Tower by narrow out-sloping ledge leading steeply upward for 25 feet. The shelf then traverses for 25 feet to the bottom of a 15-foot crack. This is followed by a series of scree-covered ledges, the Washboard. Climb the Washboard to a cliff at the upper end, and move left, up an easy pitch. Descend to a wide ledge leading right and into the angle formed by the Great Buttress and the face proper. Mount about twenty-five feet on easy rocks. Three routes present themselves, namely (left to right): “Fresh Air Traverse,” “Shaky-Leg Crack,” and “Direct Crack.”

“Fresh Air Traverse,” minimum class 5, 100 feet. Traverse left (S) around a large rectangular block, cross a gap in the ledge requiring a long step, and work out about 20 feet to the left. At this point climb upward over a rather smooth face to a steep, broken chimney leading gradually back to the right. Ascend the chimney and traverse right at the head. The lead ends almost directly above the start. The climber is now in the angle at the foot of the Grand Staircase, a series of shelves.

“Shaky-Leg Crack,” class 5, very strenuous. First ascent June 9, 1936, by Morgan Harris, James N. Smith and Neil Ruge. Climb a few feet above the beginning of the Fresh Air Traverse. The belayer should be anchored on a narrow, partly overhung ledge. A shoulder-stand will be advisable, and the difficult crack above merits at least two safety pitons.

“Direct Crack,” class 6. First ascent July 4, 1953, by John D. Mendenhall. The crack splits the wall about forty feet south of the right-hand cliffs, and requires about four pitons.

Above any of these three variations, climb the Grand Staircase to the wall at its head, and move left into a narrow squeeze chimney or crack (one piton advisable). A register will be found after the pitch is conquered. Traverse upward and right until easy rocks lead to the summit above. Ortenburger Variation: ascend blocks above the register to the ridge, thence north to summit. (References to Route 6: SCB, 1932, 53; 1935, 109. American Alpine Journal, 1931, 415.)

Route 7. Southeast face. Minimum class 5. First ascent October 11, 1941, by John D. and Ruth Mendenhall. North of the base of the long couloir separating Whitney and Keeler Needle rises a buttress capped by an impressive gendarme. The buttress is separated from the eastern precipices of Whitney by an overhanging chimney. Ascend the buttress on easy class 4 rocks until one can traverse into and cross the chimney above the overhang. The thousand feet of rock remaining requires but two anchor pitons. The couloir between Whitney and Keeler is dangerously unsound, having claimed three lives. (Reference to Route 7: SCB, 1942, 131.)

Keeler Needle (14,128)

This is the first needle south of Mt. Whitney. West side. Class 1. First ascent unknown. A short climb over small blocks from the Mount Whitney trail.

Day Needle (14,110 approx.)

This is the second needle south of Mt. Whitney. West side. Class 1. First ascent unknown. From the Mount Whitney trail, climb easy blocks to the summit.

Third Needle (14,100 approx.)

Route 1. West side. Class 1. First ascent unknown. Make a short climb over easy blocks from the Mount Whitney trail to the summit.

Route 2. East buttress. Class 4 and 5, with one class 6 pitch. First ascent September 5, 1948, by John D. Mendenhall, Ruby Wacker and John Altseimer. Walk up glaciated slabs west of Mirror Lake, south of Pinnacle Ridge. Ascend easy blocks where the Ridge ends against the east buttress of the Third Needle. Rope up and ascend the south edge of the rib to about 13,600 feet elevation, where one crosses to the east face and climbs the class 6 chimney. Some distance above, traverse right into a rotten, bottomless chimney. The rib eases off, and one shifts from the south to the north side via a convenient cleft. A providential ledge leads to easy rocks just north of the summit (SCB, 1949, 145).

Route 3. East face. Class 4, with one class 5 traverse. First ascent September 3, 1939, by John D. Mendenhall and Ruth Dyar (Mendenhall). Follow Route 2 to roping-up point. Class 3 climbing leads upward and to the left into an easy gully, which is capped by an abrupt overhang above the half-way point. Turn the difficulty by a short class 5 traverse to the right. Climb directly to the summit of the ridge by class 4 rocks, emerging upon the watershed between Third Needle and Day Needle. Routes 2 and 3 are recommended for those desiring roped routes combined with maximum accessibility (SCB, 1940, 129).

Pinnacle Ridge (13,050)

This serrated ridge separates the middle and north forks of Lone Pine Creek. A class 4 traverse of the ridge can be made in either direction (John D. Mendenhall and Nelson P. Nies, July 10, 1935). The views are among the finest in the entire Sierra, for the eastern battlements of Mount Whitney tower above, and Thor Peak dominates the view to the east.

Pinnacle Pass Needle (12,300). Northwest of Pinnacle Pass. Maximum class 4. First ascent. September 7, 1936, by Robert K. Brinton, Glen Dawson and William Rice. Ascend a severe crack on the corner facing Whitney. Traverse a short arÍte to the summit.

Thor Peak (12,301)

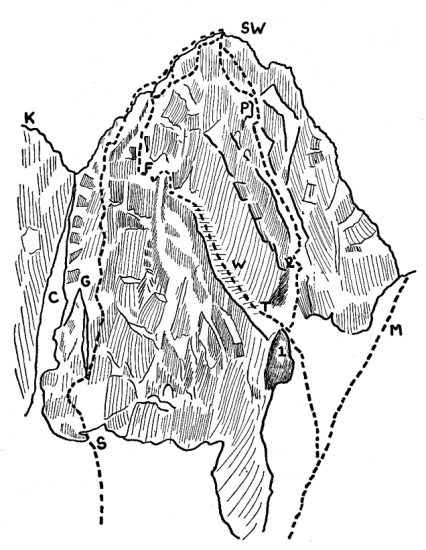

This spectacular wall, separating the middle and north forks of Lone Pine Creek, towers to the north of Bighorn Park. The south face provides interesting climbs. Routes 1 and 4 are shown on Sketch 27 of Thor’s south wall.

Route 1. Southwest side. Class 1. First ascent by Norman Clyde. Climb ledges north of Mirror Lake to a sloping, sandy plateau southwest of the peak. Mount talus and scree to the notch south of the peak, and traverse to the northeast side, thence to summit.

Route 2. West arÍte. Class 2. First descent September 7, 1936, by Robert K. Brinton, Glen Dawson and William Rice. A pleasant route to the summit over large granite blocks.

Route 3. Southeast chimney. Class 4. First ascent September 7, 1936, by William Rice, Robert K. Brinton and Glen Dawson. Climb to trees on the wall north of Bighorn Park. From a point near the highest trees, traverse along a ledge to left. Ascend a very difficult vertical chimney. Follow ledge back to right. Mount cracks and ledges to a large red-tinged pinnacle standing out from the wall. Between the pinnacle and the main face, traverse right to a gully sloping up to left. An unusually well-defined ledge to left leads to summit.

[click to enlarge] Sketch 27. South wall of Thor Peak. |

| 1 | Route 1 | P | Pink Perch |

| 4 | Route 4 | V | Variation, Route 4 |

Route 4. South face. Class 5. First ascent September 4, 1937, by Howard Koster, Arthur B. Johnson and James N. Smith. Follow the Mount Whitney trail above Bighorn Park to top of switchbacks. A broad, brush-covered talus fan leads up to the right. Mount into a crack separating the main peak from Mirror Point to the southwest. Ascend the crack for two pitches, and traverse east along a series of ledges. Climb via a crack to the “Pink Perch,” a high reddish ledge. Descend a crack eastward for a hundred feet. Two or three delicate steps place one in a vertical crack a few feet out on the face. Climb two pitches upward in the crack to a shelf behind a gendarme. Turn to the right and make a delicate face climb of 15 feet; easier going completes a 70-foot lead. Climb another pitch on fine, high-angle blocks, then traverse west high above the Pink Perch. Follow a series of ledges, which lead up into a recess under a 10-foot wall of cornice blocks, and emerge upon the arÍte a few hundred feet east of the summit (SCB, 1938, 105).

Variation. Class 4. First descent September 3, 1940, by Carl Jensen, Howard Koster, Wayland Gilbert and Elsie Strand. The Pink Perch may also be reached by a small gully from the east. Take the trail from Bighorn. At top of switchbacks, leave trail and go up broad gully to where a wide ledge comes in from the right. Follow this ledge about two-thirds its length, then take a steep narrow gully leading diagonally left across the face directly to the Pink Perch.

Mirror Point. This is the southern buttress of Thor Peak, rising immediately north of Mirror Lake.

Route 1. West side. Class 1.

Route 2. Southeast face. Maximum class 4. First ascent September 6, 1936, by William Rice and Robert K. Brinton. Mount the talus slope northwest of Bighorn Park (northeast of Mirror Lake) to an apron. Climb up and around the apron to the left, ascending series of cracks above. The most difficult pitch is an overhanging 20-foot crack. The route works gradually to the left (S).

Mount Muir (14,025)

This peak provides a most impressive view of the entire region.

Route 1. West face. Class 2. First ascent unknown. A monument of rocks stands in a shallow chute at the point where one leaves the Mount Whitney trail. The summit, 400 feet above, is plainly visible. Climb over loose talus and blocks, and head for the ridge to the right, at the point where the talus blends into the summit rocks. Traverse to the left and up a short crack to the small summit cap.

Route 2. East buttress, north side. Minimum class 4. First ascent July 11, 1935, by Nelson P. Nies and John D. Mendenhall. The route lies up the well-defined buttress that interrupts the sweep of the east wall. Rapid climbing will be encountered by maintaining a course just to the right of the ridge. When approximately half-way up the rib, swing left into a well-fractured chute that climbs back to the right, between two gendarmes. Behind the gendarmes, turn left and ascend large blocks to notch beneath summit. Keep slightly to left and attain summit via steep trough (SCB, 1936, 100).

Route 3. East buttress, south side. Class 4. First ascent September 1, 1935, by Arthur B. Johnson and William Rice. From near the start of Route 2, climb the face of the buttress for a few pitches. Where the blocks become difficult, traverse down a ledge into a gully under the south face of the arÍte. Follow the trough to its head, where a 70-foot vertical crack appears in the very corner. Ascend the crack and steep blocks to the arÍte. Work right and up under gendarme to a fractured chute, and rejoin Route 2 (SCB, 1936, 101).

Peak 12,811 (Wotan’s Throne)

This point rises in cliffs from the southwest shore of Mirror Lake. Northwest arÍte. Class 2. First ascent 1933, by Norman Clyde. From flats north of Consultation Lake there is a prominent class 2 couloir leading directly to the summit. East Chimney. Class 2. First ascent by Chester Versteeg July 10, 1937. Climb northernmost of three short chimneys that breach the southeast wall of summit rocks.

Point 13,777 (Discovery Pinnacle)

Immediately south of new Whitney Pass. First ascent September, 1873, by Clarence King and Knowles. Class 2 from the south.

Mount Hitchcock (13,188)

Class 1. This has a long, ascending nivated slope rising from the southwest. The northeast side is a steep, impressive cliff. The first ascent was claimed by Frederick Wales, September 1881. Ascend the west shoulder from Crabtree Meadows and proceed along the plateau to the summit.

Photographs: SCB, 1910, plate 40; 1937, plate 3 (from Whitney).

Mount McAdie (13,800)

The mountain consists of three summits. The north peak is the highest, with the middle next in elevation.

North peak. Class 3. First ascent 1922 by Norman Clyde. From the slopes north of Arc Pass climb nearly to the summit of the middle peak. Descend to the col between the middle and north summits, traverse to the west side of the north peak, and climb upwards.

Middle peak. Class 2. First ascent June 1928 by Norman Clyde. From the slopes north of Arc Pass, ascend directly to the summit.

South peak. Class 2. First ascent June 12, 1936, by Oliver Kehrlein, Chester Versteeg and Tyler Van Degrift. From Arc Pass, ascend chimney on southeast face to summit. A class 3 traverse of a knife-edge enables one to attain the middle summit.

Mount Mallory (13,870)

Route 1. Class 2. First ascent June, 1925, by Norman Clyde. From Mount Irvine, go around the east shoulder of Mount Mallory to the easy south slope.

Route 2. From south of Arc Pass. Class 2. From south of Arc Pass, go up one of several chutes just to the north of the prominent peak on the edge of the LeConte plateau. Then follow Route 1.

Route 3. West side. Class 3. First ascent July 18, 1936, by Oliver Kehrlein, Chester Versteeg and Tyler Van Degrift. Ascend a wide couloir from Arc Pass to a point northwest of summit. Mount talus blocks to a horizontal crack running north to south. Class 3 rocks lead from upper end of crack to summit.

Route 4. Traverse from the north peak. Class 3. First ascent July 26, 1931, by Howard Sloan. Traverse from the head of the chute between Irvine and Mallory along the crestline, over the north peak, and into the notch between the north and main peaks. Thence climb to the summit. A variation is to climb about half-way up the north peak, and traverse by a series of easy ledges across its east face, onto the arÍte a hundred feet above the notch, and thence into notch and up north arÍte of main peak.

Route 5. East side. Class 2 from Tuttle Creek.

Mount Irvine (13,790)

This ragged granite peak can be climbed by any of the chutes leading from Arc Pass to the high plateau east of crest, from which the summit is easily accessible.

Route 1. Class 1. First ascent June, 1925, by Norman Clyde. From Arc Pass, ascend a deep chute to the ridge to the east. Cross the ridge, descending slightly. Go around to the southeast side and ascend final easy rocks to summit.

Route 2. Class 1. The peak can be climbed directly from the Middle Fork of Lone Pine Creek.

Peak 12,004 (Mt. Candlelight)

This peak is south of Whitney Portal.

Route 1. Class 1. First ascent August 31, 1940, by Chester Versteeg. From Lower Meysan Lake, east of the peak, ascend a scree slope south of the prominent rock face to the saddle, thence to the summit.

Route 2. Class 3. Ascend the rock face directly above Lower Meysan Lake, up a chimney. Traverse left on a broad ledge for 25 feet, and follow an orange-colored dike to within 10 feet of top. Traverse right on a narrow ledge for 10 feet, then ascend 500 feet of scree to the summit.

The north face (above Whitney Portal Campground) offers interesting class 5 climbs, as yet uncompleted.

Lone Pine Peak (12,951)

This is an imposing summit when seen from Lone Pine; from the west and northwest, the northeast arÍte presents an interesting profile.

Route 1. Class 1. First ascent 1925, by Norman Clyde. Climb to a point west-southwest of the peak and ascend a talus slope to the high plateau, which presents a steep front to the east. Follow the plateau to the summit.

Route 2. North-northeast ridge. Long class 5 (6 pitons). First ascent September, 1952, by A. C. Lembeck and Ray W. Van Aken. From Whitney Portal drive east to summer home tract. Follow Meysan Lake trail, and take left branch where it divides. This trail drops to stream. Ascend north talus of Lone Pine Peak, bearing easterly. Cross under the ridge, gain the ridge’s crest, and follow (class 3) to first large step (visible from Lone Pine). Ascend step, bearing to right (1 piton). The next pitch is strenuous (2 pitons). Climb an overhanging slab with layback to a platform, which is followed by a smooth chimney (3 pitons). Easy class 3 and 4 climbing over towers leads to the final summit blocks. Traverse horizontally east for 10 feet under the overhang, then upward by means of a crack. Make a hand traverse of crack to chimney. Ascend chimney, cross ridge to west, and follow minimum class 4 rocks to summit.

Mount Newcomb (13,484)

Class 1. First ascent August 22, 1936, by Max Eckenburg and Bob Rumohr. Ascent made from Mount Pickering. Follow down north ridge, across saddle, skirt pinnacles on the west, thence up southwest ridge to summit.

Mount Chamberlin (13,173)

First ascent by J. H. Czock, date unknown. Class 1 by west arÍte.

Mount Pickering (13,481)

Southeast arÍte. Class 2. First ascent July 16, 1936, by Chester Versteeg, Tyler Van Degrift and Oliver Kehrlein. Climb from Rock Creek Basin past Primrose Lake via the southeast arÍte to the plateau, thence to summit.

Joe Devel Peak (13,328)

Class 2. First ascent September 20, 1875, by Wheeler Survey party, route unknown. Climbed July 7, 1937, by Owen L. Williams via the southeast arÍte. Records from 1875 to 1908 were found. The ascent is class 2 from the south or southwest.

Mount Guyot (12,305)

Class 1. This mountain lies west of the main crest and affords a fine view of both the Whitney Region and the Great Western Divide. First ascent 1881 by William Wallace.

The Miter (12,784)

South face. Class 3. First ascent July 18, 1938, by R. S. Fink. From Rock Creek, ascend a low ridge just south of Iridescent Lake and follow this to a saddle on the south side of the mountain. Climb many ledges, bearing slightly to the west. Then go in an easterly direction on the upper slope.

Mount LeConte (13,960)

Route 1. Northwest ridge. Class 2. First ascent June 1935 by Norman Clyde. “Followed ridge running southeast from Mount Mallory; thence on ridge around to southwest “shoulder of mountain, encountered 20-foot drop, retraced shelf for 100 yards, dropped down to and came up chimney, passing below 20-foot drop, thence to summit.” The head of the chute near the summit is the most difficult part of the climb. This route is still used by parties approaching the peak from the north.

Route 2. Northeast face. Class 3. First ascent September 7, 1952, by Steve Wilkie, Barbara Lilley, Wes Cowan, George Wallerstein and June Kilbourne. From Meysan Lake, ascend a loose, narrow chute to the plateau between LeConte and Mallory (also readily accessible from northwest). Cross the plateau to the cairn at the base of LeConte. Traverse easterly 200 yards. Now on northeast face but short of the east arÍte, ascend directly to the summit.

Route 3. East arÍte. Class 3. First recorded ascent June 12, 1937, by Gary Leech, Bill Blanchard and Hubert North. Follow Route 2 to the cairn. Traverse for 450 or 500 yards to a chimney on the east face and follow up the chimney to a point near the summit; leave the chimney and complete climb on east arÍte.

Route 4. From the west. Class 4. First ascent July 17, 1936, by Oliver Kehrlein, Tyler Van Degrift and Chester Versteeg. Climb talus fan about 200 yards north of the east end of Iridescent Lake, the only lake in the recess; thence up a long couloir to a point below crest. Traverse to the northwest for 60 feet, at which point climb directly east toward the summit about 400 feet distant.

Route 5. From the west. Class 2. Follow Route 4, except that the traverse northwest is followed until a difficult chute in north face leads to summit.

Photograph: SCB, 1896, plate 32 (Summit rocks).

Corcoran Mountain (13,733)

This is one-half mile south of Mount LeConte, and the most northerly of three summits just south of LeConte.

Route 1. From the north. Class 1. First ascent 1933, by Howard S. Gates. Climb from Iridescent Lake up a chute to the saddle in the crest north of peak; thence up easy rocks to the summit.

Route 2. From the south. Class 2. First ascent July 20, 1938, by R. S. Fink. Ascend west side of the main crest to the notch just south of the peak, thence up south ridge.

Mount Langley (14,042)

First ascent 1871, by Clarence King and Paul Pinson.

Route 1. From Army Pass on the south. Class 1.

Route 2. From Rock Creek on the west. Class 1. Climb a wide chute, one-half mile south of a point directly west of the summit, to a level bench. Thence follow an easy arÍte in a northeasterly direction to the summit.

Route 3. North face. Class 3. First recorded ascent August 1937 by Howard S. Gates and Nelson P. Nies. From a bench south of Tuttle Creek, climb to the base, thence southwest to a chimney blocked at the head. Climb out of the chimney to the south ledge, thence traverse southeast, then southwest to a ridge. Follow the ridge to the summit.

Route 4. East-southeast ridge. Class 3. From the northernmost large Cottonwood Lake, ascend talus to the westernmost of two saddles in the east-southeast ridge. Follow the crest of the broad ridge and plateau to the summit.

Photograph: SCB, 1910, plate 39.

Peak 12,819 (2 SE of Mount Langley)

First ascent July 16, 1938, by R. S. Fink, who established Routes 1 and 2.

Route 1. Class 1. From Diaz Creek climb southwest in a chute to the col on the main ridge west of the peak, thence east around the south slope to the summit.

Route 2. Class 1. From approximately 11,200 in Diaz Creek, ascend the north slope, bearing slightly east, and thence to the summit.

Route 3. From Cottonwood Lakes. Class 1. First ascent 1938 by Bill Roberts. From the lakes, climb the south slopes to the summit. l

Peak 12,437 (The Major General)

Rising northwest of Army Pass, this peak was first ascended by Chester and Lillian Versteeg August 8, 1937. From Rock Creek, climb shallow couloir slightly northwest of summit, thence up rock mass. Final pinnacle is short class 3.

Photographs: Of the Whitney Region in general: SCB, 1894, plate 6 (from Williamson); 1929, plate 22 (from Langley), plate 21 (from Mallory); 1937, plate 4 (north from Whitney), plate 7 (from southeast), plates 8, 9 (aerial from east); 1938, plate 39 (climbing); 1947, opposite page 31 (along Whitney trail); 1950, 36-37 (Sierra Crest from Langley).

Next: Kaweahs & Great Western Divide • Contents • Previous: Kings-Kern Divide

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/climbers_guide/whitney.html