HALF DOME

(4,737 feet in height.)

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Discovery > Chapter 5 >

| Previous: Chapter IV • Index • Next: Chapter VI |

Date of Discovery—First White Visitors—Captain Joe Walker’s Statement—Ten-ie-ya’s Cunning—Indian Tradition—A lying Guide—The Ancient Squaw—Destroying Indian Stores—Sweat-houses—The Mourner’s Toilet—Sentiment and Reality—Return to Head-quarters.

The date of our discovery and entrance into the Yosemite was about the 21st of March, 1851. We were afterward assured by Ten-ie-ya and others of his band, that this was the first visit ever made to this valley by white men. Ten-ie-ya said that a small party of white men once crossed the mountains on the North side, but were so guided as not to see it; Appleton’s and the People’s Encyclopedias to the contrary notwithstanding.* [*Captain Joe Walker, for whom “Walker’s Pass” is named, told me that he once passed quite near the valley on one of his mountain trips; but that his Ute and Mono guides gave such a dismal account of the cañons of both rivers, that he kept his course near to the divide until reaching Bull Creek, he descended and went into camp, not seeing the valley proper.]

It was to prevent the recurrence of such an event, that Ten-ie-ya had consented to go to the commissioner’s camp and make peace, intending to return to his mountain home as soon as the excitement from the recent outbreak subsided. The entrance to the Valley had ever been carefully guarded by the old chief, and the people of his band. As a part of its traditionary history, it was stated: “That when Ten-ie-ya left the tribe of his mother and went to live in Ah-wah-ne, he was accompanied by a very old Ah-wah-ne-chee, who had been the great ‘medicine man’ of his tribe.”

It was through the influence of this old friend of his father that Ten-ie-ya was induced to leave the Mono tribe, and with a few of the descendants from the Ah-wah-nee-chees, who had been living with the Monos and Pai-Utes, to establish himself in the valley of his ancestors as their chief. He was joined by the descendants from the Ah-wah-ne-chees, and by others who had fled from their own tribes to avoid summary Indian justice. The old “medicine man” was the counselor of the young chief. Not long before the death of this patriarch, as if endowed with prophetic wisdom, he assured Ten-ie-ya that while he retained possession of Ah-wah-ne his band would increase in numbers and become powerful. That if he befriended those who sought his protection, no other tribe would come to the valley to make war upon him, or attempt to drive him from it, and if he obeyed his counsels he would put a spell upon it that would hold it sacred for him and his people alone; none other would ever dare to make it their home. He then cautioned the young chief against the horsemen of the lowlands (the Spanish residents), and declared that, should they enter Ah-wah-ne, his tribe would soon be scattered and destroyed, or his people be taken captive, and he himself be the last chief in Ah-wah-ne.

For this reason, Ten-ie-ya declared, had he so rigidly guarded his valley home, and all who sought his protection. No one ventured to enter it, except by his permission; all feared the “witches” there, and his displeasure. He had “made war upon the white gold diggers to drive them from the mountains, and prevent their entrance into Ah-wah-ne.”

The Yo-sem-i-tes had been the most warlike of the mountain tribes in this part of California; and the Ah-wah-ne-chee and Mono members of it, were of finer build and lighter color than those commonly called “California Digger Indians.” Even the “Diggers” of the band, from association and the better food and air afforded in the mountains, had become superior to their inheritance, and as a tribe, the Yosemites were feared by other Indians.

The superstitious fear of annihilation had, however, so depressed the warlike ardor of Ten-ie-ya, who had now become an old man, that he had decided to make efforts to conciliate the Americans, rather than further resist their occupancy of the mountains; as thereby, he hoped to save his valley from intrusion. In spite of Ten-ie-ya’s cunning, the prophecies of the “old medicine” man have been mostly fulfilled. White horsemen have entered Ah-wah-ne; the tribe has been scattered and destroyed. Ten-ie-ya was the last chief of his people. He was killed by the chief of the Monos, not because of the prophecy; nor yet because of our entrance into his territory, but in retribution for a crime against the Mono’s hospitality. But I must not, Indian like, tell the latter part of my story first.

After an early breakfast on the morning following our entrance into the Yosemite, we equipped ourselves for duty; and as the word was passed to “fall in,” we mounted and filed down the trail to the lower ford, ready to commence our explorations.

The water in the Merced had fallen some during the night, but the stream was still in appearance a raging torrent. As we were about to cross, our guide with earnest gesticulations asserted that the water was too deep to cross, that if we attempted it, we would be swept down into the cañon. That later, we could cross without difficulty. These assertions angered the Major, and he told the guide that he lied; for he knew that later in the day the snow would melt. Turning to Captain Boling he said: “I am now positive that the Indians are in the vicinity, and for that reason the guide would deceive us.” Telling the young Indian to remain near his person, he gave the order to cross at once.

The ford was found to be rocky; but we passed over it without serious difficulty, although several repeated their morning ablutions while stumbling over the boulders.

The open ground on the north side was found free from snow. The trail led toward “El Capitan,” which had from the first, been the particular object of my admiration.

At this time no distinctive names were known by which to designate the cliffs, waterfalls, or any of the especial objects of interest, and the imaginations of some ran wild in search of appropriate ones. None had any but a limited idea of the height of this cliff, and but few appeared conscious of the vastness of the granite wall before us; although an occasional ejaculation betrayed the feelings which the imperfect comprehension of the grand and wonderful excited. A few of us remarked upon the great length of time required to pass it, and by so doing, probably arrived at more or less correct conclusions regarding its size.

Soon after we crossed the ford, smoke was seen to issue from a cluster of manzanita shrubs that commanded a view of the trail. On examination, the smoking brands indicated that it had been a picket fire, and we now felt assured that our presence was known and our movements watched by the vigilant Indians we were hoping to find. Moving rapidly on, we discovered near the base of El Capitan, quite a large collection of Indian huts, situated near Pigeon creek. On making a hasty examination of the village and vicinity, no Indians could be found, but from the generally undisturbed condition of things usually found in an Indian camp, it was evident that the occupants had but recently left; appearances indicated that some of the wigwams or huts had been occupied during the night Not far from the camp, upon posts, rocks, and in trees, was a large caché of acorns and other provisions.

HALF DOME (4,737 feet in height.) |

NORTH DOME AND ROYAL ARCHES (3,568 feet in height.) |

Abundant evidences were again found to indicate that the huts here had but just been deserted; that they had been occupied that morning. Although a rigid search was made, no Indians were found. Scouting parties in charge of Lieutenants Gilbert and Chandler, were sent out to examine each branch of the valley, but this was soon found to be an impossible task to accomplish in one day. While exploring among the rocks that had fallen from the “Royal Arches” at the southwesterly base of the North Dome, my attention was attracted to a huge rock stilted upon some smaller ones. Cautiously glancing underneath, I was for a moment startled by a living object. Involuntarily my rifle was brought to bear on it, when I discovered the object to be a female; an extremely old squaw, but with a countenance that could only be likened to a vivified Egyptian mummy. This creature exhibited no expression of alarm, and was apparently indifferent to hope or fear, love or hate. I hailed one of my comrades on his way to camp, to report to Major Savage that I had discovered a peculiar living ethnological curiosity, and to bring something for it to eat. She was seated on the ground, hovering over the remnants of an almost exhausted fire. I replenished her supply of fuel, and waited for the Major. She neither spoke or exhibited any curiosity as to my presence.

Major Savage soon came, but could elicit nothing of importance from her. When asked where her companions were, she understood the dialect used, for she very curtly replied “You can hunt for them if you want to see them"! When asked why she was left alone, she replied “I am too old to climb the rocks"! The Major—forgetting the gallantry due her sex—inquired “How old are you?” With an ineffably scornful grunt, and a coquettish leer at the Major, she maintained an indignant silence. This attempt at a smile, left the Major in doubt as to her age.

CATHEDRAL ROCKS (2,660 feet in height.) |

The detachment sent down the trail reported the discovery of a small rancheria, a short distance above the “Cathedral Rocks,” but the huts were unoccupied. They also reported the continuance of the trail down the left bank. The other detachments found huts in groups, but no Indians. At all of these localities the stores of food were abundant.

Their cachés were principally of acorns, although many contained bay (California laurel), Piñon pine (Digger pine), and chinquepin nuts, grass seeds, wild rye or oats (scorched), dried worms, scorched grasshoppers, and what proved to be the dried larvae of insects, which I was afterwards told were gathered from the waters of the lakes in and east of the Sierra Nevada. It was by this time quite clear that a large number of Ten-ie-ya’s band was hidden in the cliffs or among the rocky gorges or cañons, not accessible to us from the knowledge we then had of their trails and passes. We had not the time, nor had we supplied ourselves sufficiently to hunt them out. It was therefore decided that the best policy was to destroy their huts and stores, with a view of starving them out, and of thus compelling them to come in and join with Ten-ie-ya and the people with him on the reservation. At this conclusion the destruction of their property was ordered, and at once commenced. While this work was in progress, I indulged my curiosity in examining the lodges in which had been left their home property, domestic, useful and ornamental. As compared with eastern tribes, their supplies of furniture of all kinds, excepting baskets, were meagre enough.

These baskets were quite numerous, and were of various patterns and for different uses. The large ones were made either of bark, roots of the Tamarach or Cedar, Willow or Tule. Those made for gathering and transporting food supplies, were of large size and round form, with a sharp apex, into which, when inverted and placed upon the back, everything centres. This form of basket enables the carriers to keep their balance while passing over seemingly impassable rocks, and along the verge of dangerous precipices. Other baskets found served as water buckets. Others again of various sizes were used as cups and soup bowls; and still another kind, made of a tough, wiry grass, closely woven and cemented, was used for kettles for boiling food. The boiling was effected by hot stones being continually plunged into the liquid mass, until the desired result was obtained.

The water baskets were also made of “wire-grass;” being porous, evaporation is facilitated, and like the porous earthen water-jars of Mexico, and other hot countries, the water put into them is kept cool by evaporation. There were also found at some of the encampments, robes or blankets made from rabbit and squirrel skins, and from skins of water-fowl. There were also ornaments and musical instruments of a rude character. The instruments were drums and flageolets. The ornaments were of bone, bears’ claws, birds’ bills and feathers. The thread used by these Indians, I found was spun or twisted from the inner bark of a species of the asclepias or milk-weed, by ingeniously suspending a stone to the fibre, and whirling it with great rapidity. Sinews are chiefly used for sewing skins, for covering their bows and feathering their arrows. Their fish spears were but a single tine of bone, with a cord so attached near the centre, that when the spear, loosely placed in a socket in the pole, was pulled out by the struggles of the fish, the tine and cord would hold it as securely as though held by a barbed hook.

There were many things found that only an Indian could possibly use, and which it would be useless for me to attempt to describe; such, for instance, as stag-horn hammers, deer prong punches (for making arrow-heads), obsidian, pumice-stone and salt brought from the eastern slope of the Sierras and from the desert lakes. In the hurry of their departure they had left everything. The numerous bones of animals scattered about the camps, indicated their love of horse-flesh as a diet.

Among these relics could be distinguished the bones of horses and mules, as well as other animals, eaten by these savages. Deers and bears were frequently driven into the valley during their seasons of migration, and were killed by expert hunters perched upon rocks and in trees that commanded their runways or trails; but their chief dependence for meat was upon horseflesh.

Among the relics of stolen property were many things recognized by our “boys,” while applying the torch and giving all to the flames. A comrade discovered a bridle and part of a riata or rope which was stolen from him with a mule while waiting for the commissioners to inquire into the cause of the war with the Indians! No animals of any kind were kept by the Yosemites for any length of time except dogs, and they are quite often sacrificed to gratify their pride and appetite, in a dog feast. Their highest estimate of animals is only as an article of food. Those stolen from the settlers were not kept for their usefulness, except as additional camp supplies. The acorns found were alone estimated at from four to six hundred bushels.

During our explorations we were on every side astonished at the colossal representations of cliffs, rocky cañons and water-falls which constantly challenged our attention and admiration.

Occasionally some fragment of a garment was found, or other sign of Indians, but no trail could be discovered by our eyes. Tired and almost exhausted in the fruitless search for Indians, the footmen returned to the place at which they had left their horses in the cañons, and in very thankfulness caressed them with delight.

In subsequent visits, this region was thoroughly explored and names given to prominent objects and localities.

While searching for hidden stores, I took the opportunity to examine some of the numerous sweat-houses noticed on the bank of the Merced, below a large camp near the mouth of the Ten-ie-ya branch. It may not be out of place to here give a few words in description of these conveniences of a permanent Indian encampment, and the uses for which they are considered a necessity.

The remains of these structures are sometimes mistaken for Tumuli. They were constructed of poles, bark, grass and mud. The frame-work of poles is first covered with bark, reeds or grass, and then the mud—as tenacious as the soil will admit of—is spread thickly over it. The structure is in the form of a dome, resembling a huge round mound. After being dried by a slight fire, kindled inside, the mud is covered with earth of a sufficient depth to shed the rain from without, and prevent the escape of heat from within. A small opening for ingress and egress is left; this comprises the extent of the house when complete, and ready for use. These sweat-baths are used as a luxury, as a curative for disease, and as a convenience for cleansing the skin, when necessity demands it, although the Indian race is not noted for cleanliness.

As a luxury, no Russian or Turkish bath is more enjoyed by civilized people, than are these baths by the Mountain Indians. I have seen a half dozen or more enter one of these rudely constructed sweat-houses, through the small aperture left for the purpose. Hot stones are taken in, the aperture is closed until suffocation would seem impending, when they would crawl out reeking with perspiration, and with a shout, spring like acrobats into the cold waters of the stream. As a remedial agent for disease, the same course is pursued, though varied at times by the burning and inhalation of resinous boughs and herbs.

In the process for cleansing the skin from impurities, hot air alone is generally used. If an Indian had passed the usual period for mourning for a relative, and the adhesive pitch too tenaciously clung to his no longer sorrowful countenance, he would enter, and re-enter the heated house, until the cleansing had become complete.

The mourning pitch is composed of the charred bones and ashes of their dead relative or friend. These remains of the funeral pyre, with the charcoal, are pulverized and mixed with the resin of the pine. This hideous mixture is usually retained upon the face of the mourner until it wears off. If it has been well compounded, it may last nearly a year; although the young—either from a super-abundance of vitality, excessive reparative powers of the skin, or from powers of will—seldom mourn so long. When the bare surface exceeds that covered by the pitch, it is not a scandalous disrespect in the young to remove it entirely; but a mother will seldom remove pitch or garment until both are nearly worn out.

In their camps were found articles from the miners’ camps, and from the unguarded “ranchman.” There was no lack of evidence that the Indians who had deserted their villages or wigwams, were truly entitled to the soubriquet of “the Grizzlies,” “the lawless.”

Although we repeatedly discovered fresh trails leading from the different camps, all traces were soon lost among the rocks at the base of the cliffs. The débris or talus not only afforded places for temporary concealment, but provided facilities for escape without betraying the direction. If by chance a trail was followed for a while, it would at last be traced to some apparently inaccessible ledge, or to the foot of some slippery depression in the walls, up which we did not venture to climb. While scouting up the Ten-ie-ya cañon, above Mirror Lake, I struck the fresh trail of quite a large number of Indians. Leaving our horses, a few of us followed up the tracks until they were lost in the ascent up the cliff. By careful search they were again found and followed until finally they hopelessly disappeared.

Tiring of our unsuccessful search, the hunt was abandoned, although we were convinced that the Indians had in some way passed up the cliff.

During this time, and while descending to the valley, I partly realized the great height of the cliffs and high fall. I had observed the height we were compelled to climb before the Talus had been overcome, though from below this appeared insignificant, and after reaching the summit of our ascent, the cliffs still towered above us. It was by instituting these comparisons while ascending and descending, that I was able to form a better judgment of altitude; for while entering the valley,—although, as before stated, I had observed the towering height of El Capitan,—my mind had been so preoccupied with the marvelous, that comparison had scarcely performed its proper function.

The level of the valley proper now appeared quite distant as we looked down upon it, and objects much less than full size. As night was fast approaching, and a storm threatened, we returned down the trail and took our course for the rendezvous selected by Major Savage, in a grove of oaks near the mouth of “Indian Cañon.”

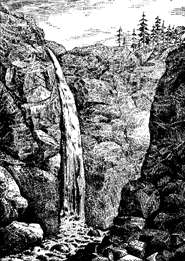

GLACIER FALL. (550 feet in height.) |

The duties of the day had been severe on men and horses, for beside fording the Merced several times, the numerous branches pouring over cliffs and down ravines from the melting snow, rendered the overflow of the bottom lands so constant that we were often compelled to splash through the water-courses that later would be dry. These torrents of cold water, commanded more especial attention, and excited more comment than did the grandeur of the cliffs and water-falls. We were not a party of tourists, seeking recreation, nor philosophers investigating the operations of nature. Our business there was to find Indians who were endeavoring to escape from our charitable intentions toward them. But very few of the volunteers seemed to have any appreciation of the wonderful proportions of the enclosing granite rocks; their curiosity had been to see the stronghold of the enemy, and the general verdict was that it was gloomy enough.

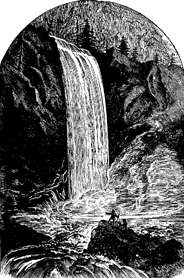

Tired and wet, the independent scouts sought the camp and reported their failures. Gilbert and Chandler came in with their detachments just at dark, from their tiresome explorations of the southern branches. Only a small squad of their commands climbed above the Vernal and Nevada falls; and seeing the clouds resting upon the mountains above the Nevada Fall, they retraced their steps through the showering mist of the Vernal, and joined their comrades, who had already started down its rocky gorge. These men found no Indians, but they were the first discoverers of the Vernal and Nevada Falls, and the Little Yosemite. They reported what they had seen to their assembled comrades at the evening camp-fires. Their names have now passed from my memory—not having had an intimate personal acquaintance with them—for according to my recollection they belonged to the company of Capt. Dill.

While on our way down to camp we met Major Savage with a detachment who had been burning a large caché located in the fork, and another small one below the mouth of the Ten-ie-ya branch. This had been held in reserve for possible use, but the Major had now fired it, and the flames were leaping high. Observing his movements for a few moments we rode up and made report of our unsuccessful efforts. I briefly, but with some enthusiasm, described my view from the cliff up the North Cañon, the Mirror Lake view of the Half Dome, the Fall of the South Cañon and the view of the distant South Dome. I volunteered a suggestion that some new tactics would have to be devised before we should be able to corral the “Grizzlies” or “smoke them out.” The Major looked up from the charred mass of burning acorns, and as he glanced down the smoky valley, said: “This affords us the best prospect of any yet discovered; just look!” “Splendid!” I promptly replied, Yo-sem-i-te must be beautifully grand a few weeks later, when the foliage and flowers are at their prime, and the rush of water has somewhat subsided. Such cliffs and water-falls I never saw before, and I doubt if they exist in any other place.”

VERNAL FALL. (350 feet in height.) |

NEVADA FALL. (600 feet in height.) |

The more practical tone and views of the Major dampened the ardor of my fancy in investing the valley with all desirable qualities, but as we compared with each other the experiences of the day, it was very clear that the half had not yet been seen or told, and that repeated views would be required before any one person could say that he had seen the Yosemite. It will probably be as well for me to say here that though Major Savage commanded the first expedition to the valley, he never revisited it, and died without ever having seen the Vernal and Nevada Falls, or any of the views belonging to the region of the Yosemite, except those seen from the valley and from the old Indian trail on our first entrance.

We found our camp had been plentifully supplied with dry wood by the provident guard, urged, no doubt, by the threatening appearances of another snow-storm. Some rude shelters of poles and brush were thrown up around the fires, on which were placed the drying blankets, the whole serving as an improvement on our bivouac accomodations. The night was colder than the previous one, for the wind was coming down the cañons of the snowy Sierras. The fires were lavishly piled with the dry oak wood, which sent out a glowing warmth. The fatigue and exposure of the day were forgotten in the hilarity with which supper was devoured by the hungry scouts while steaming in their wet garments. After supper Major Savage announced that “from the very extensive draft on the commissary stores just made, it was necessary to return to the ‘South Fork.’” He said that it would be advisable for us to return, as we were not in a condition to endure delay if the threatened storm should prove to be a severe one; and ordered both Captains Boling and Dill to have their companies ready for the march at daylight the next morning.

While enjoying the warmth of the fire preparatory to a night’s rest, the incidents of our observations during the day were interchanged. The probable heights of the cliffs was discussed. One official estimated “El Capitan” at 400 feet!! Capt. Boling at 800 feet; Major Savage was in no mood to venture an opinion. My estimate was a sheer perpendicularity of at least 1500 feet. Mr. C. H. Spencer, son of Prof. Thomas Spencer, of Geneva, N.Y.,—who had traveled quite extensively in Europe,—and a French gentleman, Monsieur Bouglinval, a civil engineer, who had joined us for the sake of adventure, gave me their opinions that my estimate was none too high; that it was probable that I was far below a correct measurement, for when there was so much sameness of height the judgment could not very well be assisted by comparison, and hence instrumental measurements alone could be relied on. Time has demonstrated the correctness of their opinions. These gentlemen were men of education and practical experience in observing the heights of objects of which measurement had been made, and quietly reminded their auditors that it was difficult to measure such massive objects with the eye alone. That some author had said: “But few persons have a correct judgment of height that rises above sixty feet.”

I became somewhat earnest and enthusiastic on the subject of the valley, and expressed myself in such a positive manner that the “enfant terrible” of the company derisively asked if I was given to exaggeration before I became an “Indian fighter.” From my ardor in description, and admiration of the scenery, I found myself nicknamed “Yosemity” by some of the battalion. It was customary among the mountain men and miners to prefix distinctive names. From this hint I became less expressive, when conversing on matters relating to the valley. My self-respect caused me to talk less among my comrades generally, but with intimate friends the subject was always an open one, and my estimates of heights were never reduced.

Major Savage took no part in this camp discussion, but on our expressing a design to revisit the valley at some future time, he assured us that there was a probability of our being fully gratified, for if the renegades did not voluntarily come in, another visit would soon have to be made by the battalion, when we could have opportunity to measure the rocks if we then desired. That we should first escort our “captives” to the commissioners’ camp on the Fresno; that by the time we returned to the valley the trails would be clear of snow, and we would be able to explore to our satisfaction. Casting a quizzing glance at me, he said: “The rocks will probably keep, but you will not find all of these immense water-powers.”

Notwithstanding a little warmth of discussion, we cheerfully wrapped ourselves in our blankets and slept, until awakened by the guard; for there had been no disturbance during the night. The snow had fallen only to about the depth of an inch in the valley, but the storm still continued.

By early dawn “all ready” was announced, and we started back without having seen any of the Indian race except our useless guide and the old squaw. Major Savage rode at the head of the column, retracing our trail, rather than attempt to follow down the south side. The water was relatively low in the early morning, and the fords were passed without difficulty. While passing El Capitan I felt like saluting, as I would some dignified acquaintance.

The cachés below were yet smouldering, but the lodges had disappeared.

At our entrance we had closely followed the Indian trail over rocks that could not be re-ascended with animals. To return, we were compelled to remove a few obstructions of poles, brush and loose rocks, placed by the Indians to prevent the escape of the animals stolen and driven down. Entire herds had been sometimes taken from the ranches or their ranges.

After leaving the valley, but little difficulty was encountered. The snow had drifted into the hollows, but had not to any extent obscured the trail, which we now found quite hard. We reached the camp earlier in the day than we had reason to expect. During these three days of absence from headquarters, we had discovered, named and partially explored one of the most remarkable of the geographical wonders of the world.

| Previous: Chapter IV • Index • Next: Chapter VI |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/discovery_of_the_yosemite/05.html