| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > First Tourist Visitors >

Next: Chapter 8 • Index • Previous: Chapter 6

|

God is the author, men are only the players.

—Balzac.

|

|

There are two worlds; the world that we can measure with line and rule, and

the world that we feel with our hearts and imaginations.

—Leigh hunt’s

Men, Women, and Books.

|

|

And this our life, exempt from public haunt,

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, Sermons in stones and good in everything.

—Shakespeare’s

As You Like It.

|

Upon the return of the Mariposa Battalion to the settlements—the exploits of which are briefly outlined in chapters two and three—and when, like

“The broken soldier, kindly bade to stay,

Sat by his fire, and talked the night away.”

They recounted their

“Moving accidents by flood and field,”

But little seems to have been said, and that little very casually, about the marvelous grandeur of the Yo Semite, at least but little found its way, impressibly, to the public through the press of that day. It was therefore only a historical verity to confess that, but for the contemplated publication of an illustrated California monthly—afterwards issued for a number of years in San Francisco—its merely fortuitous mention would probably have escaped the attention of the writer altogether as it seemed to have done that of the public. As the account given, however, mentioned the existence of “a water-fall nearly a thousand feet high,” it was sufficient to suggest a series of ruminating queries. A water-fall a thousand feet in height, and that is in California? A thousand feet? Why, Niagara is only one hundred and sixty-four feet high! A thousand feet!! The scrap containing this valuable and startling statement, meager though it was, was carefully treasured.

About the twentieth of June, 1855 [Editor’s note: the correct date is June 27, 1855.—dea] —some four years after Yo Semite had been first seen by white men, and when entirely unaware of the sublime mountain scenery afterwards found there—the “water-fall a thousand feet high” induced the writer to form a party to visit it. That party—whose names are also given in a previous chapter—consisted of the then well-known artist, Thomas Ayres (who had been specially engaged by the writer to portray the majesty and beauty of the lofty water-fall expected to be found there), Walter Millard, and J. M. Hutchings. Mr. Alexander Stair afterwards joined us at Mariposa.

Upon our arrival at Mariposa, whence the principal members of the battalion had started out against the Indians, in 1851, to our surprise, the very existence of such a place as the Yo Semite Valley, was almost unknown to a very large proportion of its residents. Numerous and persistent inquiries, however, eventually revealed the fact that a man named—say—Carter, was one of those who had gone out against the Indians, in 1851. Accordingly, Mr. Carter’s residence was anxiously inquired for, and finally found about two miles below town. Mr. Carter was at home.

“Is this Mr. Carter?”

“Yes, sir; it is.”

“You were a member of Company B, Captain Boling’s, I believe, during the Indian campaign of 1851?”

“Yes, Sir; I was.”

“Did you go to the Yo Semite Valley with that company?”

“I did, Sir.”

“Then you are the very man that we wanted to find. We have just arrived here from San Francisco, and want to learn our way to that valley. Will you, therefore, please to give us such plain directions, that we cannot possibly misunderstand them, so that we can get there?” He looked at us in bewildered and nervous astonishment, and replied:—

“Me, Sir? I couldn’t do it. I am not worth a worn-out old pick at that business. Why, bless your life, I only live about two miles from town, and if I don’t notice particularly what I am about, I am sure to take the wrong trail, and get lost. The fact is, Sir, I am about the poorest man you could have come to, on that business. Now if you had only gone to John Fowler’s, John could have told you all about it. John Fowler is the man that you want.”

“Where does he live?”

“Only about a mile and a quarter from here. You couldn’t very well miss the trail, if you were to turn to the left at the bottom of this ravine; about two hundred yards from there, by bearing a little to the right, you will cross Blanket Ridge into Shay’s Gulch; well, you follow that down nearly to the mouth, where you go over a rocky point to Slum-gullion Creek; here, let me caution you to keep a sharp lookout for miner’s prospecting holes, that are full of soft mud, although apparently dry and hard on the top; for, if you ever walk into one of those, the chances are against your ever getting out, to say nothing about the bright red color you would be painted, if you could come out at all. Well, John Fowler’s cabin is on the west side of Slum-gullion Creek, about three-quarters of a mile above where you first strike it. If John hasn’t gone to town—and I don’t think this is his day for going—he can give you all the directions.”

| |

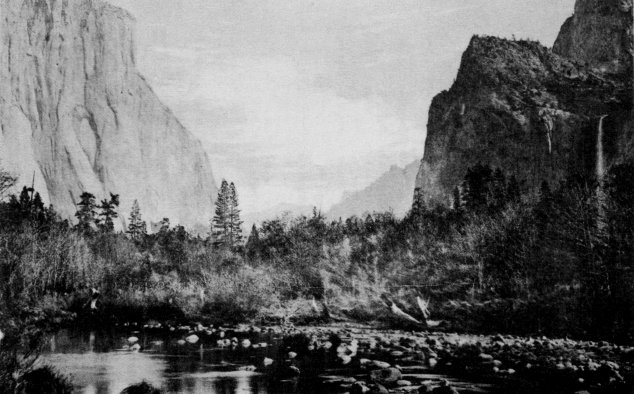

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| Enchantment Point—Too-un-yah. | |

| (See page 400.) | |

So we thanked Mr. Carter for his information, wished him good-day, and set out in search of “John Fowler’s.” Many were the

That we witnessed by the way, and which, of themselves, would have been sufficient, under ordinary circumstances, to fully compensate us for our jaunt, and even now they beguiled and rewarded our every footstep. Perseverance is generally crowned

|

| SEE! I’VE STRUCK IT. |

Accordingly, Mr. Lovejoy was sought after, and found. From him we ascertained, not the route to the Yo Semite Valley, but that he had been the undisputed owner of a bad sick-head-ache, which he had kept in unquestioned possession for several successive days, when on the march; and that, as a consequence, he had noticed nothing outside, or apart from that. He could not tell us anything. Finally, a number of regretful shadows began to file into the furrows of his sun-burned face, and to gather among the wrinkles at the corners of his eyes, possibly at the thought of the distance we had journeyed to find him, and the little satisfaction

|

| MINER’S CABIN. |

In this dilemma we met Captain Boling, the gentleman in charge of Company B, of the Mariposa volunteers, and who, being really very desirous of assisting us in every possible manner, confessed that although he considered himself about as good as an expert in wood-craft, could not now find the way to Yo Semite; as the trails were all overgrown with grass and weeds; and, as a matter of course, if he could not find the way there himself, it would be simply impossible for him to describe it so that we could find it. “No,” said he, “if I were in your place, gentlemen, and wanted to go to the Yo Semite, I should first make a trip to John Hunt’s store on the Fresno—it is thirty miles directly out of your way—but there you will find the few Yo Semite Indians living of the entire tribe; tell Mr. Hunt your wants and wishes, also say to him that I sent you, and I am satisfied that he will provide you with a couple of good Indian guides who can take you straight to the spot.” We considered this most excellent advice, and, so expressing it, carried out his recommendations.

Mr. Hunt received us very kindly, and, acceding to our request, procured us two of the most intelligent and trustworthy Indians that he had, whose names were Kos-sum and So-pin; and on the following day we set out upon our enigmatical course for the valley.

|

| HO! FOR THE MOUNTAINS. |

Believe me there is an indescribable charm steals over the heart when wandering among the untrodden fastnesses of the mountains for the first time, especially under circumstances similar to ours. We were entering a mysterious country—to us unknown. The journey before us was full of uncertain lights and shadows—so might its ending possibly be. Our guides were Indians, and from a tribe that bore no enviable reputation; and were, moreover, strangers to us. They were conducting us among the unbroken solitudes of the forest, and away from civilization.

The roads near the settlements left behind, there was scarcely the outline of an Indian trail visible; unused as they had been, all were now overgrown, or covered up with leaves, as dead as the hopes of the Indians that once trod them. The boughs of seemingly impenetrable thickets were parted asunder, and our way forced through them in silence. Not a sound relieved the unbroken stillness of our discursive progress. Even the woods were voiceless with the songs of birds. A band of deer might occasionally shoot across an opening, or a covey of grouse beat the air heavily with their wings in clumsy flight; but these were all that could be seen or heard of life, except our own desultory or nonsensical converse.

|

| WE TAKE A “CUT-OFF." |

|

| AND WE FIND A “CUT-OFF." |

Of course we knew more about the way to go than they did—and proved it! There was one comforting solace to all our mishaps—they brought an enjoyable laugh to the Indian guides. These, and their meals, were always in order, and ever pleasantly taken. Successively and successfully, we passed through dark and apparently interminable forests, penetrated brushy thickets, ascended rocky ridges, and descended talus-covered slopes, until, on the afternoon of the third day of our deeply interesting expedition, we suddenly came in full view of

The inapprehensible, the uninterpretable profound, was at last opened up before us. That first vision into its wonderful depths was to me the birth of an indescribable “first love” for scenic grandeur that has continued, unchangeable, to this hour, and I gratefully treasure the priceless gift. I trust, moreover, to be forgiven for now expressing the hope that my long afterlife among the angel-winged shadows of her glorious cliffs, has given heart-felt proof of the abiding purity, and strength of that “first love” for Yo Semite.

This mere glimpse of the enchanting prospect seemed to fill our souls to overflowing with gratified delight, that was only manifest in unbidden tears. Our lips were speechless from thanksgiving awe. Neither the language of tongue nor pen, nor the most perfect successes of art, can approximately present that picture. It was sublimity materialized in granite, and beauty crystallized into object forms, and both drawing us nearer to the Infinite One.

It would be difficult to tell how long we looked lingeringly at this unexpected revelation; for,

“With thee conversing, I forget all time.”

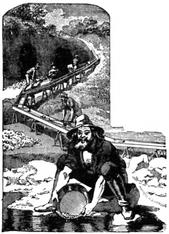

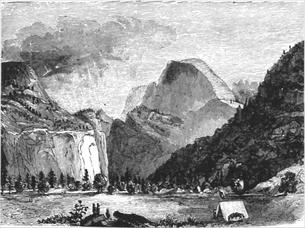

Our sketches finished—the first probably ever taken—the fast lengthening shadows admonished a postponement of that intensely pleasurable experience, and in response we hastened our descent to the camp-ground on the floor of the valley.

| |

|

Sketched by Thos. Ayres, June 20, 1855—first ever taken.

[Editor’s note: the correct date is June 27, 1855.—dea] | |

| GENERAL VIEW OF THE YO SEMITE VALLEY. |

It was late in the night before the nervous excitement, created by our imposing surroundings, permitted “sleep to come to our eyes, or slumber to our eyelids;” and, even then, from our dreams arose the shadowy forms of a new species of genii! After a substantial breakfast, made palatable by that best of all sauces, a good appetite, and the sun had begun to wink at us from between the pine trees on the mountain tops, or to throw shimmering lances down among the peaks and crags, we commenced our entrancing pilgrimage up the valley.

A few advancing footsteps brought us to the foot of a fall, whose charming presence had long challenged our admiration; and, as we stood watching the changing drapery of its watery folds, the silence was eventually broken by my remark, “Is it not as graceful, and as beautiful, as the veil of a bride?” to which Mr. Ayres rejoined, “That is suggestive of a very pretty and most apposite name. I propose that we now baptize it, and call it, ‘The Bridal Veil Fall,’ as one that is both characteristic and euphonious.” This was instantly concurred in by each of our party, and has since been so known, and called, by the general public. This, then, was the time, and these the circumstances, attending

About its Indian appellation and signification, with its legends and associations, more will be said in a future chapter.

Our progress upon the south side of the valley—the one on which we had entered it—was soon estopped by an immense deposit of rocky talus, that compelled us to ford the Merced River. Advancing upward upon its northern bank, after threading our way among trees, or around huge blocks of granite that were indiscriminately scattered about, passing scene after scene of unutterable sublimity, and sketching those deemed most noteworthy; again crossing and recrossing the river, we found ourselves in immediate proximity to the “water-fall a thousand feet high,” and which had been the magnetic incentive to our visit to Yo Semite. This, from our measurements of prostrate pine-trees, by which was estimated the height of those standing (as we had no instruments with us adapted to such purposes), we deduced its altitude to be from fifteen to eighteen hundred feet! By subsequent actual measurements of the State Geological survey, its absolute height is given at 2,634 feet; with which those made by the Wheeler survey, under Lieutenant M. M. Macomb, U. S. A., very closely approximate. This inadequate realization of heights at Yo Semite is often strikingly manifest in visitors, on their first advent, even at the present day.

|

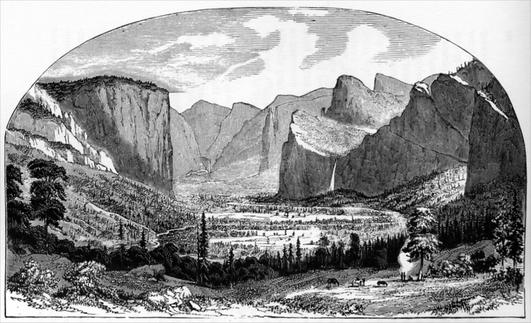

| "TO-COY-AE” and “TIS-SA-ACK.” (North, and South, or, Half Dome.) |

| [From a sketch taken in 1855.] |

It will be both unnecessary and inexpedient to detain the reader, now, with detailed recitals of the many objects of interest witnessed on this ramble, inasmuch as they are to be more fully presented with illustrations, in succeeding chapters. It may, however, be desirable here to mention that our explorations were limited to the valley, terminating at Mirror Lake—so named by our party. We did not see the “Vernal” or “Nevada” Falls, and only the Too-lool-we-ack, or Glacier Cañon Fall, from the Mirror Lake Trail. But we had seen sufficient to fill our hearts with gratitude that the All Father had created so many majestic and beautiful objects for human eyes to feast upon, that thereby humanity might grow nearer to Him, and thenceforth be nobler, higher, purer, and better for the sight.

We spent five glorious days in luxurious scenic banqueting here, the memory of which is, like the mercies of the Almighty, “new every morning, and fresh every evening.” We left it reluctantly, even when our sketch and note-books were as full to repletion with elevating treasures, as our souls were with loving veneration for their wonderful Author. I believe that each one of us was responsively in sympathy with Byron, as expressed in the following lines from “Childe Harold:"—

“I love not man the less, but Nature more,

From these our interviews, in which I steal

From all I may be, or have been before,

To mingle with the Universe, and feel

What I can ne’er express, yet cannot all conceal.”

Our return to the settlements was the signal for the curious and inquisitive to besiege and interview us with eager questionings, to ascertain what we had seen and experienced; for there was a vague novelty in such a trip in those days. Among these came the editor of the Mariposa Gazette, Mr. L. A. Holmes (the memory of whom is still lovingly enshrined in the hearts of all who intimately knew him), and requested a full rehearsal of all the sights we had seen. Compliance with so reasonable a request was attended with a modest exposition of our sketches, accompanied with explanatory remarks to elucidate them. These ended, Mr. Holmes thus addressed the writer:—

“Mr. H., I have been quite ill all this week. My paper has to make an appearance day after to-morrow or—, and I have not been able to write a line for it, yet. You can therefore see that you can infinitely oblige me, if you were to sit down at that table there and throw me off an article upon what you have seen in this county, to help me out.”

The response promptly came, “All right. I will do so. I take real pleasure in helping a man out of a corner, if I can, when he finds himself in one.” Accordingly, a descriptive sketch of what had been seen was written for Mr. Holmes, and was published in the Mariposa Gazette or about July 12, 1855.

This sketch happened to enlist the attention of journalists, was copied into most of the leading newspapers of the day, and for the first time the attention of the public, generally, was awakened towards the marvelous scenery of the Yo Semite Valley. In this connection it should be remembered that it is not by any means claimed that ours was the first party making the trip there, nor that the first article written concerning it; but, inasmuch as the sentiment accredited to Cicero,

“Justice renders to every man his due,”

Will, in the interests of historical accuracy, permit the statement that, whether from preoccupied attention, or other causes, the fact remains the same that the Yo Semite Valley, at that time, was as a sealed book to the general public, and that it was our good fortune to be instrumental in opening its sublime pages to the public eye, that it might be “known and read of all men.” Fiat justitia, ruat coelum.

In and around Mariposa the new revelation seems to have become the theme of many tongues, as plans were discussed and parties organized for visiting it. Early the ensuing August two companies of kindred spirits, one of seventeen from Mariposa, and another of ten from Sherlock’s Creek, an adjacent mining camp, started in search of the new scenic El Dorado; the former party engaged the same Indians as guides who had conducted us there so successfully, and the latter was led by Mr. E. W. Haughton, who had accompanied the Savage expedition, under Captain Boling, in 1851. The members of the last-mentioned company were

And as this was an event of untold importance in the development of the stupendous scenery of Yo Semite, great pleasure is taken in transcribing portions of Mr. James H. Lawrence’s deeply interesting and graphic account of it—he being one of the party—given in the Overland Monthly for October, 1884:—

As I must trust to memory alone for the names of my companions,

|

| STEADY, THERE! STEADY! |

E. W. Haughton, who was with the Boling expedition in 1851, was our guide. Two pack mules loaded with blankets, a few cooking utensils, and some provisions, constituted our camp outfit; while a half-breed blood-hound, whose owner claimed that he was"the best dog on the Pacific Coast,” and who answered to the name of “Ship,” trotted along with the pack-mules. There was some talk about going mounted, but the proposition was voted down by a handsome majority, on the ground that superfluous animals were “too much bother.”

In fancy, I see them yet, and hear the ringing chorus, the exultant whoop, and the genuine, unrestrained laughter at the camp-fire. It would be worth a year of humdrum civilized society life to recall the reality of one week of the old time.

One evening, after a series of dare-devil escapades for no other purpose except to demonstrate how near a man can come to breaking his neck and miss it, some one suggested an expedition up the main river, above the valley. Haughton was appealed to for information. He favored the proposition, and said he would cheerfully make one of the party. As for information, he had none to give; neither he nor any of the Boling expedition ever dreamed of attempting it. They came on business—not to see sights or explore for new fields of wonder. Their mission was hunting Indians. There was no sign of a trail. It was a deep, rough cañon, filled with immense bowlders, through which the river seethed and roared with a deafening sound, and there had never been seen a foot-print of white man or Indian in that direction. The cañon was considered impassable.

There was a chorus of voices in response.

“That’s the word.”

“Say it again.”

“Just what we are hunting.”

“We want something rough.”

“We’ll tackle that cañon in the morning.”

“An early start, now.”

It was so ordered. “With the first streak of daylight you’ll hear me crow,” was Connor’s little speech as he rolled himself in his blankets. Next morning we were up and alive, pursuant to programme. Everybody seemed anxious to get ahead.

Three of us—Milton J. Mann, G. C. Pearson, and the writer of this sketch—lingered to arrange the camp-fixtures, for everybody was going up the cañon. When we came to the Glacier Cañon, or Taloolweack, our friends were far in advance of us. We could hear them up the cañon shouting, their voices mingling with the roar of the waters. A brief consultation, and we came to the resolve to diverge from the main river and try to effect an ascent between that stream and the cañon. It looked like a perilous undertaking, and there were some doubts as to the result; nevertheless, the conclusion was to see how far we could go. Away up, up, far above us, skirting the base of what seemed to be a perpendicular cliff, there was a narrow belt of timber. That meant a plateau or strip of land comparatively level. If we could only reach that, it was reasonable to suppose that we could get around the face of the cliff. “Then we will see sights,” was the expression of one of the trio. What we expected to discover somewhere up the main stream was a lake or perhaps a succession of lakes—such having been the result of the explorations up the Pyweah Cañon, and mountain lakes being not unfrequently noted as a feature of the sources of mountain streams.

But to reach the plateau—that was the problem. It was a fearful climb. Over and under and around masses of immense rocks, jumping across chasms at imminent risk of life and limb, keeping a bright lookout for soft places to fall, as well as the best way to circumvent the next obstacle, after about three hours’ wrestling, “catch as catch can,” with that grim old mountain-side, we reached the timber. Here, as we had surmised, was enough of level ground for a foothold, and here we took a rest, little dreaming of the magnificent scene in store for us when we rounded the base of the cliff.

The oft-quoted phrase, “A thing of beauty is a joy forever,” was never more fully realized. The picture is photographed on the tablets of my memory in indelible colors, and is as fresh and bright to-day as was the first impression twenty-nine years ago. To the tourist who beholds it for the first time, the Nevada Fall, with its weird surroundings, is a view of rare and picturesque beauty and grandeur. The rugged cliffs, the summits fringed with stunted pine and juniper bounding the cañon on the southern side, the “Cap of Liberty” standing like a huge sentinel overlooking the scene at the north, the foaming caldron at the foot of the fall, the rapids below, the flume where the stream glides noiselessly but with lightning speed over its polished granite bed, making the preparatory run for its plunge over the Vernal Fall, form a combination of rare effects, leaving upon the mind an impression that years cannot efface. But the tourist is in a measure prepared. He has seen the engravings and photographic views, and read descriptions written by visitors who have preceded him. To us it was the opening of a sealed volume. Long we lingered and admiringly gazed upon the grand panorama, till the descending sun admonished us that we had no time to lose in making our way campward.

Our companions arrived long ahead of us. “Supper is waiting,” announced the chief cook; “ten minutes later and you would have fared badly; for we are hungry as wolves.”

“Reckon you’ve been loafing,” chimed in another. “You should have been with us. We struck a fall away up at the head of the cañon, about four hundred feet high.”

“Have you? We saw your little old four hundred-foot fall and go you four hundred better"—and then we proceeded to describe our trip, and the discovery which was its result.

The boys wouldn’t have it. None of them were professional sports, but they would hazard a little on a horse-race, a turkey-shooting, or a friendly game of “draw"—filling the elegant definition of the term “gambler” as given by one of the fraternity, viz.: “A gentleman who backs opinion with coin.” Connor was the most voluble. He got excited over it, and made several rash propositions.

“Tell me,” said he, ‘that you went further up the cañon than we did? We went till we butted up against a perpendicular wall which a wild cat couldn’t scale. The whole Merced River falls over it. Why, a bird couldn’t fly beyond where we went. Of course, you think you have been further up the river, but you are just a little bit dizzy. I’ll go you a small wad of gold-dust that the fall you have found is the same as ours.”

Connor was gently admonished to keep his money—to win it was like finding it in the road—nay, worse; it would be downright robbery—but to make the thing interesting we would wager a good supper—best we could get in camp, with the"trimmings"—upon our return home, that we had been higher up the cañon, and that our fall beat theirs in altitude. It was further agreed that one of us should accompany the party as guide.

“Better take along a rope—it might help you over the steep places,” was a portion of our advice, adding by way of caution to “hide it away from Connor” when they returned, for “he would feel so mean that he would want to hang himself.”

To Pearson, who was ambitious to show off his qualities as a mountain guide, was delegated the leadership—an arrangement which was mutually satisfactory—”Milt” agreeing with me that a day’s rest would be soothing and helpful. Besides, we had laid a plan involving a deep strategy to capture some of those immense trout, of which we had occasional glimpses, lying under the bank, but which were too old and cunning to be beguiled with the devices of hook and line.

The plan was carried out, on both sides, to a successful issue. On our part, we secured two of the largest trout ever caught in the valley, and had them nicely dressed, ready for the fry-pan, when our companions returned, which was about sunset. Soon as they came within hailing distance, their cheerful voices rang out (Connor’s above all the rest), “We give it up!” They were in ecstasies, and grew eloquent in praise of the falls and scenery, at the same time paying us many compliments.

A courier was dispatched to notify the Mariposa party of our discovery. It was a surprise to them, but they had made their arrangements to leave for home early the next morning. They regretted the necessity, but business arrangements compelled their departure.

Upon the return of our party to San Francisco, the writer, being in pleasant intimacy with the late Rev. W. A. Scott, D.D., and family, paid them a visit, when the subject of the scenery of the Yo Semite was discussed, and sketches shown. The doctor manifested remarkable interest in the theme, and added: “Mr. H., I am badly in need of a vacation, and if I can induce a number of my friends to join me, I should like very much to visit such a marvelous locality. I shall esteem it a personal favor to myself if you will dine with us at an early day, on which occasion I will invite a few intimate friends to join us, and discuss the subject of visiting that astonishingly magnificent creation.” This invitation was cordially accepted, and in due time and order the proposed dinner party assembled, when the matter was thoroughly canvassed, and a company formed for making the journey. On the evening of their arrival in Mariposa, on the way up, it was their good fortune to meet some of the members of the Mariposa party, just returned from Yo Semite; from these additional information was received, and timely suggestions made, born of recent experiences. The Indian guides, Kos-sum and So-pin, having satisfactorily conducted themselves on each former occasion, and being now at liberty, were reŽngaged by the Scott party. After a very satisfactory and soul-satisfying jaunt, Dr. Scott, upon his return to San Francisco, gave several eloquent discourses, and published some tersely written articles upon it. His magnetic enthusiasm largely contributed to the development of an interest in the minds of the public, to witness such sublime scenes as those he had so graphically portrayed. From that day to this the great valley has been visited—and by tens of thousands; but this was the inauguration of tourist travel to Yo Semite.

In October, 1855, was published a lithographic view of the Yo Semite Fall (then called Yo-Ham-i-te), from the sketch taken for the writer by Mr. Thomas Ayres, in the preceding June, and which was the first ever pictorial representation of any scene in the great valley ever given to the public.

Next: Chapter 8 • Index • Previous: Chapter 6

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/07.html