| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Milton Route >

Next: Chapter 17 • Index • Previous: Chapter 15

|

And those that paint them truest praise them most.

—Addison’s

Campaign.

|

|

Thought is deeper than all speech;

Feeling deeper than all thought; Souls to souls can never teach What unto themselves was taught.

—C. P. Cranch.

|

|

So nature deals with us, and takes away

Our playthings one by one, and by the hand Leads us to rest so gently, that we go, Scarce knowing if we wish to go or stay, Being too full of sleep to understand How far the unknown transcends the what we know.

—Longfellows

Nature.

|

Having arrived at Lathrop by the main or trunk line of the Central Pacific Railroad, and having arranged to journey via the Calaveras Big Tree Route, we enter the train bound for Stockton; and, the run being only some nine miles, it is very soon accomplished. As the country is comparatively level, there is but little to excite interest, except to those who delight in pastoral loveliness, until we are near that city. Then the suburban residences, peeping out from the umbrageous oaks, and the church spires towering above them, tell that we shall soon enter its hospitable precincts. Acting upon the suggestion made in a former chapter, “when it is possible not to be in a hurry,” with your permission, we will allow the train to depart without us this morning, and take a stroll through

This flourishing commercial city is advantageously situated at the head of a deep navigable slough, or arm of the San Joaquin River, about three miles above its junction with that stream. The luxuriant foliage of its trees, the thrifty growth of its shrubs, and plants of every kind, give voiceless commendation to its founders for choosing so desirable a situation. It is true that, as this was the head of navigation for all supplies needed in the proverbially rich gold mines of Tuolumne and Mariposa Counties, and intermediate points, it became a natural landing place; and, as such, was therefore suggestive of the suitability of this location for the building of a city. As a result, tents and cloth houses sprung up like mushrooms; but the fire of December 23, 1849, entirely swept away the last vestige of this city of cloth, and destroyed other property to the value of over two hundred thousand dollars. Almost before its ruins had ceased smouldering, however, a new and cleaner city, composed of an admixture of cloth and wood, was erected in its place. In the following spring nearly all the cloth houses were superseded by wooden ones, and as this embrio city was now in steam communication with its base of supplies at San Francisco, assurance was given of its future stability and permanence, and justified the removal of wooden structures, and their replacement by those of brick.

On the 30th of March, 1850, the first weekly newspaper was published by Messrs. Radcliffe and White, conducted by Mr. John White—afterwards well known by newspapermen in the Bay City. On the same day the first theatrical performance was given in the Assembly Room of the Stockton House, by Bingham and Fury. The first election was held on the 13th of May following, the population at that early day numbering over two thousand. The Stockton Fire Department was organized June 20 (1850), and James E. Nuttman (afterwards associated with the fire department of San Francisco) was elected chief engineer. On the 25th of July, ensuing, Stockton was incorporated as a city. May 6, 1851 another fire swept away nearly every building, and destroyed property valued at a million and a half of dollars. Nothing daunted, a new city sprung up, Phoenix-like, from its ashes; and from that day to this the march of improvement has kept commensurate progress with the spirit of the age, and the requirements of its steady development. Owing to the general healthiness of its climate, and the convenience of its location, Stockton was chosen, by an Act of the Legislature of 1853, for the erection here of a State asylum for the insane; and this, with greatly enlarged accommodation, has been continued here ever since.

|

| THE “PRAIRIE SCHOONER." |

One of the most striking features of the commerce of this city in early days, and one that well deserves to be commemorated, was the large number of heavily laden freight wagons that used to leave it for the mines. These, owing to their huge bulk and enormous carrying capacity, were, not inappropriately, denominated “Prairie Schooners,” and “Steamboats of the Plains.” They would average twenty-five thousand pounds per trip. The cost of wagons was from $900 to $1,100, and they were generally over twenty feet in length. Large mules, having the requisite strength, used to cost $350 each; and some, the finest and best, $1,400 per span. The main advantage of these large teams was the economy in teamsters, as one man could drive and tend as many as fourteen animals, always guiding them with a single line. They were drilled like soldiers, and were almost as tractable; and when a teamster cracked his whip its report was like that of a revolver.

The unusually large number of windmills are suggestive of the preferred method of irrigation and of water supply. Notwithstanding this, Stockton can boast of having

It is one thousand and two feet deep, and throws out two hundred and fifty gallons of water per minute, or three hundred and sixty thousand gallons every twenty-four hours, and to the height of nine feet above the city grade. In sinking this well, ninety-six different strata of loam, clay, micaceous sand, soft green sandstone, gravel, etc., etc., were passed through. Three hundred and forty feet from the surface, a stump of one of the big trees was found imbedded in the sand, from whence a stream of water issued to the top, although not in sufficient quantities to afford the supply desired, hence its continuance to the depth mentioned. The temperature of the water was 77° Fahrenheit.

The various strata bored through, indicate beyond question, that not only this, but nearly all other valleys were at one time inland lakes, that have been filled up and formed by the denudation and lowering of the contiguous mountains, in the unrecorded ages of the far distant past. The siliceous sediment constantly floating down all our rivers, especially during high water, is incontrovertible proof that continuous denudation is still an active force in lowering mountains, and in forming valleys.

It would make our advent here extremely interesting could we visit the tanneries, carriage factories, agricultural implement manufactories, canning establishments, the two flouring mills, woolen and paper mills, schools, free library, etc., not omitting the State asylum for the insane, which would be found a model of cleanliness and good management. After this brief outline of Stockton and its attractions, with your permission we will now resume our journey.

| |

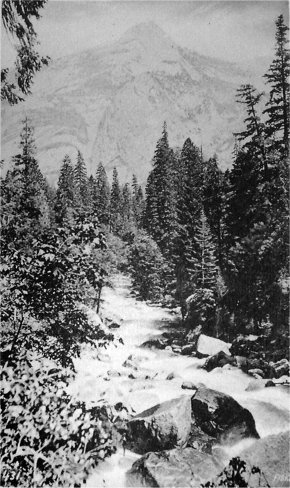

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| North Dome—To-coy-ae. | |

| (See page 383.) | |

|

THE CALAVERAS BIG TREE ROUTE,

From San Francisco, via Lathrop, Stockton, Milton, Murphy’s, Calaveras Big

|

||||

| STATIONS. | Distances in Miles. | |||

| Between consecutive points. |

From San Francisco. |

From Yo Semite Valley |

Altitude, in feet, above Sea Level. |

|

|

By Railway. |

.... | .... | 133.05 | |

| From San Francisco to— | ||||

|

Lathrop, junction of the Central Pacific with the Southern

Pacific Railroad (b c) |

94.03 | 94.03 | 39.02 | 28 |

| Stockton, on Central Pacific Railroad (a b c) | 9.02 | 103.05 | 30.00 | 29 |

| Milton, on the Stockton and Copperopolis Railroad (b c d) | 30.00 | 133.05 | .... | 376 |

|

By Carriage Road. | .... | 152.53 | ||

| From Milton to— | ||||

| Reservoir House (b c) | 6.13 | 6.13 | 146.40 | 1,013 |

| Gibson’s Station (b c d) | 10.87 | 17.00 | 135.53 | 1,570 |

| Altaville (b c) | 5.50 | 22.50 | 130.03 | 1,520 |

| Murphy’s (b c d) | 7.50 | 30.00 | 122.53 | 2,195 |

| Half-way House (b c) | 8.11 | 38.11 | 114.42 | 3.358 |

| Calaveras Big Tree Grove Hotel (a b c d) | 7.31 | 45.42 | 107.11 | 4,730 |

| Half-way House, returning (b c) | 7.31 | 52.72 | 99.80 | 3,358 |

| Murphy’s (a b c d) | 8.11 | 60.84 | 91.69 | 2,195 |

| Vallecito (b c) | 4.16 | 65.00 | 87.53 | 1,748 |

| Trail to Natural Bridge | 3.32 | 68.32 | 84.21 | .... |

| Parrott’s Ferry, Stanislaus River | 2.27 | 70.59 | 81.94 | 834 |

| Gold Spring | 3.17 | 73.76 | 78.77 | 2,014 |

| Columbia (b c) | 1.15 | 74.91 | 77.62 | 2,157 |

| Sonora (b c d) | 4.17 | 79.08 | 73.45 | 1,816 |

| Chinese Camp (a b c d) | 11.00 | 90.08 | 62.45 | 1,299 |

| Priest’s Hotel—for full details see “Big Oak Flat Route” (a b c d) | 12.11 | 102.19 | 50.34 | 2,558 |

| Tuolumne Big Tree Grove | 33.43 | 135.62 | 15.84 | 5,794 |

| Leidig’s Hotel, Yo Semite Valley (a b c d) | 15.84 | 151.46 | 1.07 | 3,851 |

| Cook’s Hotel, Yo Semite Valley (a b c d) | 0.30 | 151.76 | 0.77 | .... |

| Barnard’s Hotel, Yo Semite Valley (a b c d) | 0.77 | 152.53 | .... | .... |

|

RECAPITULATION. |

||||

| By railway | 133.05 miles. | |||

| By carriage road | 152.53 ” | |||

| ————— | ||||

| Total distance | 285.58 miles. | |||

Almost before we are fairly seated in the car, we shoot out from the station at Stockton, leaving the Central Pacific Railroad, and taking the Stockton and Copperopolis Railroad for Milton; and as we are rolling out from among the tasteful suburban residences of the city, under the gracefully pendant white oaks (Q. lobata), and past the fertile farms of this portion of the valley of the San Joaquin, a quiet, gentlemanly person, whose name is Mr. Robert Patton, politely introduces himself to us by inquiring, “May I ask what is your proposed destination, beyond Milton? I am the agent for the different stage lines leaving there for all the various points beyond.” Receiving satisfactory replies, our names are entered on the way-bill; and, upon arrival at Milton, we find a row of stages backed up against the platform, and awaiting us; with every coachman on his box, and the reins in his hand, ready for the start, the moment Mr. Patton gives him the signal. As we are supposed, on this occasion, to have chosen the route via the Calaveras Big Trees Groves, the agent has seen that ourselves and baggage are safely placed upon the Murphy’s stage, Murphy’s being en route for that point, when “All set” is shouted to the coachman, and away we go.

As every one knows, the most desirable of all places on a stage coach is that known as the “box-seat.” This is with the coachman; for, if he is intelligent, and in a good humor, he can tell you of all the sights by the way; with the personal history of nearly every man and woman you may meet; the qualities and “points” of every horse upon the road; with all the adventures, jokes, and other good things he has seen and heard during his thousand and one trips, under all kinds of circumstances, and in all sorts of weather. In short, he is a living road-encyclopedia, to be read and studied at intervals, by the occupant of the “box-seat.”

You saw that look and motion of the coachman’s head? That was at once a sign of recognition and of invitation to the privileged seat at his side, as we are old acquaintances. But, as you are a stranger, and as every excursion of real pleasure-like the happiest experiences of social life—become dependent to a very great extent upon little courtesies and kindnesses, that cost nothing, we will, if you please, set the good example of foregoing selfishness by trying to secure that seat for you. No thanks are needed, as every pleasure is doubled by being shared. Now, suppose that you are the occupant of the “box-seat,” we will make one suggestion—invite the driver to accept one of your best cigars; and, as its smoke and fragrance are rising on the air, he will gradually soften to you, and both will become better acquainted before you have traveled far.

There is a feeling of jovial, good-humored pleasurableness that steals insensibly over the spirit when the secluded residents of cities leave all the cares of a daily routine of duties behind, and the novelty of fresh scenes forms new sources of enjoyment. Especially is it so when seated comfortably in an easy-going coach; with the prospect before us of witnessing many of the most wonderful sights to be found in any country, either in the Old or New World; and, more especially, if we have learned to take a journey, as it is said that a Frenchman does his dinner, thereby enjoying it three times; first, in anticipation; second, in participation; and third, on retrospection!

For several miles before arriving at Milton, as for two or three beyond, the entire country is covered with sedimentary deposits, and water-washed gravel; and, as there are no such elemental forces at work in the present day, they offer conjectural revelations of very different conditions in the past while being suggestive of pertinent inquiries for the time and cause of change.

It is over these, for the most part treeless and rolling hills, that our road now lies. It is true there is one clump of white post oaks (Quercus Douglasii) about half a mile from Milton; remarkable only for its being the favorite resort of a species of bird, somewhat scarce in California, known as the magpie. Leaving the gravelly hills, we enter upon a graded road up a deep ravine, where shrubs and trees begin to add an interest to the landscape. At the top of the hill we reach the Reservoir House (so named from a large reservoir near, built for mining purposes), where the horses rest, and where both man and beast take water, (the former, occasionally, something a little stronger). Here are seen the first pine trees (Pinus Sabiniana).

Beyond this for many miles the country is gently undulating, yet is sparsely timbered with post oaks. At Gibson’s Station horses are exchanged, and the hungry can eat. Five miles beyond this we find ourselves at Altaville; a sprightly little mining camp, in a gold-mining district, where we cross flumes and ditches, filled with water made muddy by washing out the precious metal, and where can be Witnessed all the modus operandi of gold mining. Still our course is upward as well as onward, until we are over two thousand feet above sea level, and

Now, although the gold mines here have been among the richest, Murphy’s was but little known, beyond its more immediate surroundings, until the discovery of the Big Tree Groves of Calaveras (the first of this species ever found); and, more recently, the adjacent remarkable cave. Its proximity to, and the starting-point for, the new wonders, lifted it into world-wide notoriety, almost at a bound. It is deserving of record, however, that the discovery of those enormous trees must be credited, in a degree, to the business men of Murphy’s, through whose enterprise, incidentally, they were first seen; as the sequel, obtained from the writer from the discoverer himself, will abundantly show:—

In the spring of 1852, Mr. A. T. Dowd, a hunter, was employed by the Union Water Company, of Murphy’s, Calaveras County, to supply the workmen engaged in the construction of their canal, with fresh meat, from the large quantities of game running wild on the upper portion of their works. While engaged in this calling, having wounded a grizzly bear, and while industriously pursuing him, he suddenly came upon one of those immense trees that have since become so justly celebrated throughout the civilized world. All thoughts of hunting were absorbed and lost in the wonder and surprise inspired by the scene. “Surely,” he mused, “this must be some curiously delusive dream!” But the great realities indubitably confronting him were convincing proof, beyond question, that they were no mere fanciful creations of his imagination.

Returning to camp, he there related the wonders he had seen, when his companions laughed at him; and even questioned his veracity, which, previously, they had considered to be in every way reliable. He affirmed his statement to be true; but they still thought it “too big a story” to believe, supposing that he was trying to perpetrate upon them some first-of-April joke.

For a day or two he allowed the matter to rest; submitting, with chuckling satisfaction, to their occasional jocular allusions to “his big tree yarn,” but continued hunting as formerly. On the Sunday morning ensuing, he went out early as usual, but soon returned in haste, apparently excited by some great event, when he exclaimed, “Boys, I have killed the largest grizzly bear that I ever saw in my life. While I am getting a little something to eat, you make every preparation for bringing him in; all had better go that can possibly be spared, as their assistance will certainly be needed.”

As the big tree story was now almost forgotten, or by common consent laid aside as a subject of conversation; and, moreover, as Sunday was a leisure day, and one that generally hangs the heaviest of the seven on those who are shut out from social or religious intercourse with friends, as many Californians unfortunately were and still are, the tidings were gladly welcomed, especially as the proposition was suggestive of a day’s intense excitement.

Nothing loath, they were soon ready for the start. The camp was almost deserted. On, on they hurried, with Dowd as their guide, through thickets and pine groves; crossing ridges and cañons, flats, and ravines, each relating in turn the adventures experienced, or heard of from companions, with grizzly bears, and other formidable tenants of the mountains, until their leader came to a halt at the foot of the immense tree he had seen, and to them had represented the approximate size. Pointing to its extraordinary diameter and lofty height, he exultingly exclaimed, “Now, boys, do you believe my big tree story? That is the large grizzly I wanted you to see. Do you now think it a yarn?” By this ruse of their leader all doubt was changed into certainty, and unbelief into amazement; as, speechless with profound awe, their admiring gaze was riveted upon those forest giants.

But a short season was allowed to elapse before the trumpet-tongued press proclaimed abroad the wonder; and the intelligent and devout worshipers, in nature and science, flocked to the Big Tree Groves of Calaveras, for the purpose of seeing for themselves the astounding marvels about which they had heard so much. In a subsequent chapter will be found full particulars concerning the naming, habits, characteristics, and comparative area of this species, to which the reader is referred.

Leaving the mining village of Murphy’s behind, we pass through an avenue of trees; and, about half a mile from town, enter a narrow cañon, up which we travel, now upon this side of the stream, and now on that, as the hills proved favorable or otherwise, for the construction of the road. If our visit is supposed to be in spring or early summer, every mountain-side, even to the tops of the ridges, is covered with flowers and flowering shrubs of great variety and beauty; while, on either hand, groves of oaks and pines stand as shade-giving guardians of personal comfort.

As we continue the ascent for a few miles our course becomes more undulating and gradual; and, for the most part on the top or gently sloping sides of a dividing ridge; often through dense forests of tall, magnificent pines that are from one hundred and seventy, to two hundred and twenty feet in height; slender, and straight as an arrow. We measured one that had fallen, that was twenty inches in diameter at the base, and fourteen and a half inches in diameter at the distance of one hundred and twenty-five feet from the base. The ridges being nearly clear of an undergrowth of shrubbery; and the trunks of the trees, for fifty feet upward, or more, entirely clear of branches, the eye can wander, delightedly, for a long distance, among these captivating scenes of the forest.

At different distances upon the route, the canal of the Union Water Company winds its sinuous way on, or around, the sides of the ridge; or its sparkling contents rushed impetuously down the water-furrowed center of a ravine. Here and there an aqueduct, or cabin, or saw mill, gives variety to an ever-changing landscape. When within about four and a half miles of the Mammoth Tree Grove, the surrounding mountain peaks and ridges are boldly visible. Looking southeast, the uncovered head of Bald Mountain silently announces its solitude and distinctiveness; west, the Coast Range of mountains forms a continuous girdle to the horizon; extending to the north and east, where the snow-covered tops of the Sierras form a magnificent background to the glorious picture.

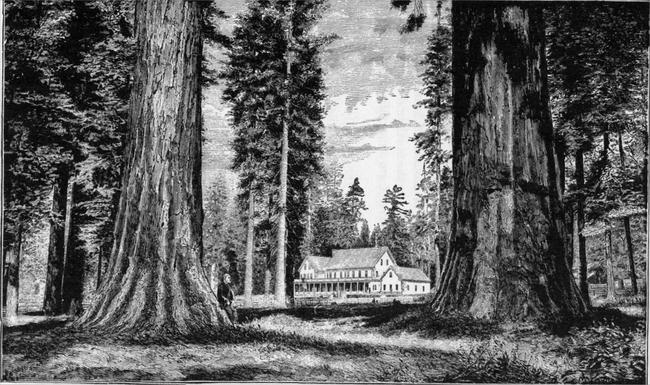

The deepening shadows of the densely timbered forest through which we are passing, by the awe they inspire, impressively intimate that we are soon to enter the imposing presence of those forest giants, the Big Trees of Calaveras, and almost before we realize our actual nearness, we catch the inviting gleam of the Calaveras Big Tree Grove Hotel. On our way to it, the carriage road passes directly between the

Each of which is over three hundred feet in height, and the larger one of the two is twenty-three feet in diameter at the base. But as no one can thoroughly enjoy the wonderful, or beautiful, with a tired body, or upon an empty stomach, let us, for the present at least, prefer the refreshing comforts and kindly hospitalities of this commodious and well-kept inn, to a walk about the grove.

According to Capt. Geo. M. Wheeler’s U. S. Geographical Survey Reports, the Calaveras Big Tree Grove Hotel is 2,535 feet above Murphy’s, and 4,730 feet above sea level. It stands in latitude 38° north, and in longitude 120°10’ west from Greenwich. The forest in which the Big Trees stand was so densely timbered

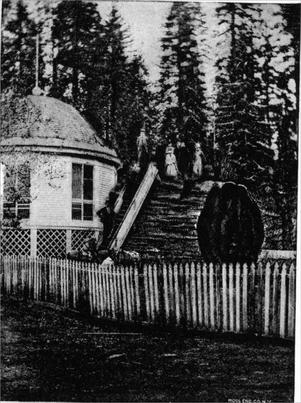

| |

| Photo by J. C. Scripture. | Moss Engraving Co., N. Y. |

| THE CALAVERAS BIG TREE GROVE HOTEL. | |

|

“The giant trees in silent majesty,

|

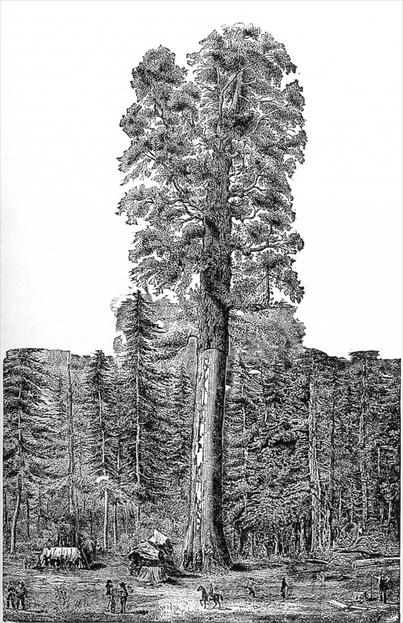

Within an area of about fifty acres there are ninety-three trees of large size, twenty of which exceed twenty-five feet in diameter at their base, and will consequently average about seventy-five feet in circumference. These would look still more imposing in proportions but for the large growth of sugar pine (Pinus Lambertiana), and the yellow pine (Pinus ponderosa). One of the latter to the southwestward of the hotel exceeds ten feet in diameter. But let us first take a walk to the

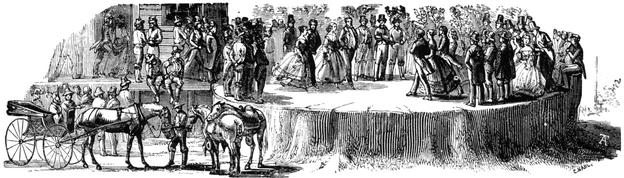

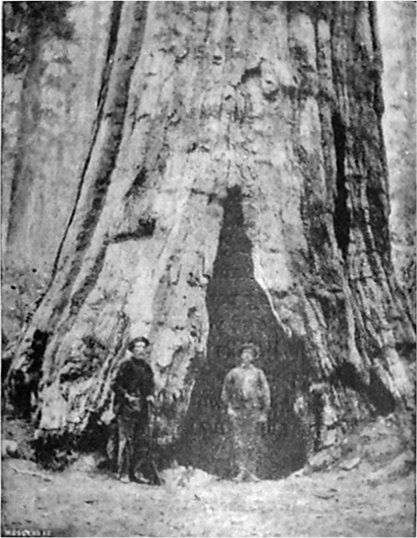

This is the stump of the original Big Tree discovered by Mr. Dowd. We can see that it is perfectly smooth, sound, and level. Its diameter across the solid wood, after the bark was removed (and which was from fifteen to eighteen inches in thickness), is twenty-five feet; although the tree was cut off six feet above the ground. However incredible it may appear, on July 4, 1854, the writer formed one of a cotillion party of thirty-two persons, dancing upon this stump; in addition to which the musicians and onlookers numbered seventeen, making a total of forty-nine occupants of its surface at one time! The accompanying sketch was made at that time, and, of course, before the present pavilion was erected over it. There is no more strikingly convincing proof, in any grove, of the immense size of the big trees, than this stump.

|

| A COTILLION PARTY OF THIRTY-TWO PERSONS DANCING ON THE STUMP OF THE MAMMOTH TREE. |

This tree was three hundred and two feet in height; and, at the ground, ninety-six feet in circumference, before it was disturbed. Some sacrilegious vandals, from the motive of making its exposition “pay,” removed the bark to the height of thirty feet; and afterwards transported it to England, where it was formed into a room; but was afterwards consumed by fire, with the celebrated Crystal Palace, at Kensington, England. This girdling of the tree very naturally brought death to it; but even then its majestic form must have perpetually taunted the belittled and sordid spirits that caused it. It is, however, but an act of justice to its present proprietor, Mr. James L. Sperry, to state that, although he has been the owner of the grove for over twenty years, that act of vandalism was perpetrated before he purchased it, or it would never have been permitted.

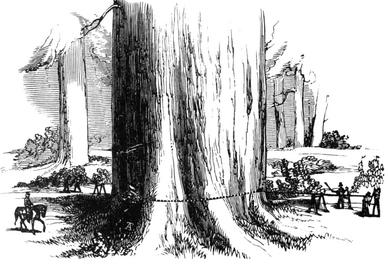

The next act in this botanical tragedy was the cutting down of the tree, in order to accommodate those who wished to carry home specimens of its wood, as souvenirs of their visit. But how to do this was the puzzling conundrum! If one could fittingly imagine so ludicrous a sight as a few lilliputian men attempting to chop down this brobdingnaggian giant, his contempt would reach its becoming climax. This, therefore, was given up as altogether too chimerical and impracticable. Finally, the plan was adopted of boring it off with pump-augers. This employed five men twenty-two days to accomplish; and after the stem was fairly severed from the stump,

|

| BORING DOWN THE ORIGINAL BIG TREE WITH PUMP-AUGERS. |

This was erected over the stump as a protection against the elements; for use on Sundays in public worship; and on weekday evenings for dancing, although I have heard that ladies complain “that there was no ‘spring’ to that floor!” Theatrical performances and concerts have taken place upon it; and, in 1858, the Big Tree Bulletin was printed and published here.

|

| Photo by J. C. Scripture. |

| TRUNK OF BIG TREE, AND PAVILION. |

Near to the pavilion and stump still lies a portion of the prostrate trunk of this magnificent tree. Of course the butt-end of the trunk is of the same diameter as the stump, where the auger marks make silent explanations of the method used in felling it.

Now, if you please, let us seek the dark recesses of this primeval forest, in spirit with uncovered head from reverential awe, feeling that we are entering the stately presence of trees that have successfully withstood the climatic changes, and storms, of more than thirty centuries. It is true that many of these grand old representatives of the dreamy past have been assailed by fire, and still proudly bear the marks of that resistless enemy; although the new growth has, in many instances, sought to cover up the scars, and renew the vigorous growth of each, as much as possible. So Nature, like a gentle mother, neglects no opportunity to heal all wounds; and, where that is impossible, covers up even deformity and decay with mosses or lichens. We can see that nearly every tree has a name (many most worthily given) and an individuality of its own; that, like human faces, are suggestive of conflict with hidden forces, that have inscribed their characteristics in every line; and were we to pause at every one, and paint the peculiarities of each, I fear that it would prove a somewhat tedious task. If you please, then, we will pass to such as are most noteworthy.

Among these once stood a most beautiful tree, graceful in form, and unexcelled in proportions; hence (as in human experiences) those very qualities at once became the most attractive to the eyes of the unfeeling spoliator. This bore the queenly name of

In the summer of 1854, the bark was stripped from its trunk, by a Mr. George Gale, for purposes of exhibition in the East, to the height of one hundred and sixteen feet. It now measures in circumference, at the base, without the bark, eighty-four feet; twenty feet from base, sixty-nine feet; seventy feet from base, forty-three feet six inches; one hundred and sixteen feet from base, and up to the bark, thirty-nine feet six inches. The full circumference at base, including bark, was ninety feet. Its height was three hundred and twenty-one feet. The average thickness of bark was eleven inches, although in places it was about two feet. This tree is estimated to contain five hundred and thirty-seven thousand feet of sound inch lumber. To the first branch it is one hundred and thirty-seven feet. The small black marks upon the tree indicate points where two and a half inch auger holes were bored, and into these rounds were inserted, by which to ascend and descend while removing the bark. At different distances upward, especially at the top, numerous dates and names of visitors have been cut. It is contemplated to construct a circular stairway around this tree. When the bark was being removed, a young man fell from the scaffolding—or, rather, out of a descending noose—at a distance of seventy-nine feet from the ground, and escaped with a broken limb. The writer was within a few yards of him when he fell, and was agreeably surprised to discover that he had not broken his neck. The accompanying engraving, representing this once symmetrical tree, is from a daguerreotype taken in 1854, immediately after the bark was removed, and correctly represents the foliage of this wonderful genus, ere the vandal’s

“Effacing fingers

Had swept the lines where beauty lingers.”

|

| "MOTHER OF THE FOREST" |

| (321 feet in height, 84 feet in circumference, without the bark.) |

Now, alas! the noble “Mother of the Forest,” dismantled of her once proud beauty, still stands boldly out, a reproving, yet magnificent ruin. Even the elements seemed to have sympathized with her, in the unmerited disgrace, brought to her by the ax; as the snows and storms of recent winters have kept hastening her dismemberment, the sooner to cover up the wrong. But a short distance from this lies the prostrate form of one that was probably the tallest sequoia that ever grew—

This tree, when standing in its primitive majesty, is accredited with exceeding four hundred feet in height, with a circumference at its base of one hundred and ten feet; and, although limbless, without bark, and even much of its sap decayed and gone, has still proportions that once could crown him king of the grove. In falling, it struck against “Old Hercules,” another old time rival in size, by which the upper part of his trunk was shivered into fragments, that were scattered in every direction. While fire has eaten out the heart of “The Father of the Forest,” and consumed his huge limbs, as of many others, the following measurements, recently taken, will prove that he was among the giants of those days, and, that “even in death he still lives.”

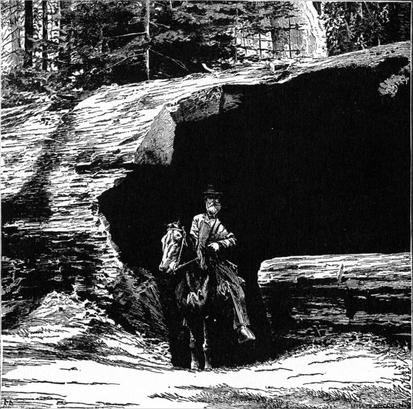

|

| Photo by J. C. Scripture. |

| HORSEMAN EMERGING FROM THE FATHER OF THE FOREST. |

But no one can approximately realize the immense proportions of this prostrate forest sire, without climbing to its top, and walking down it for its entire length; by this, moreover, he will ascertain that it was nearly two hundred feet to the first branch. At the end of the burnt cavity within, is a never-failing spring of deliciously cool water. The handsome group of stately trees that encompass the “Father of the Forest,” make it an imposing family circle; and probably assisted in originating the name.

And this is only one of the numerous vegetable giants that Time’s scythe has laid low, for, near here, lies “Old Hercules,” the largest standing tree in the grove until 1862, then being three hundred and twenty-five feet in height, by ninety-five feet in circumference, at the ground; this was blown down that year during a heavy storm; “The Miner’s Cabin,” three hundred and nineteen feet long by twenty-one in diameter, thrown over by a gale, in 1860; and “The Fallen Monarch,” which has probably been down for centuries.

Consist of ten that are each thirty feet in diameter, and over seventy that measure from fifteen to thirty feet, at the ground. Were we to linger at the foot of every one, and indulge in the portrayal of all the characteristics, size, and peculiarities of each, fascinating as they are when in their immediate presence, they would detain us too long from other scenes, and some that are especially inviting our attention; such, for instance, as

This stands about six miles southeasterly from the Calaveras Grove, and is, without doubt, the most extensive of any within the ordinary range of tourist travel; as it contains one thousand three hundred and eighty Sequoias, ranging from one foot to thirty-four feet in, diameter, and as the route thither is extremely picturesque, as well as varied and interesting, let us pay it a visit.

Threading our way through a luxuriant growth of forest trees, with here and there a long vista, which conducts the eye to scenes beyond, and gives grateful leafy shadows, and occasional patches of sunlight on our path, about a mile from the hotel we reach the top of the Divide separating the Calaveras Grove from the north fork of the Stanislaus River. Here a remarkably fine view of the Sierras is obtained, one of whose peaks, the “Dardanelles,” is twelve thousand five hundred feet above sea level. By an easy trail, with all sorts of attractive turnings upon it, the north fork of the Stanislaus River is crossed. This is the dividing line between Calaveras and Tuolumne Counties, giving the South Grove to the latter county. This river, from the bridge, is a gem of beauty. Now we wind up to the summit of the Beaver Creek Ridge, and soon descend again to Beaver Creek (where the trout-fishing is excellent); and from this point wend our way to the lower end of the grove. Here the altitude above sea level is four thousand six hundred and thirty-five feet, and the upper end, four thousand eight hundred and twenty feet.

The large number of these immense trees, from thirty feet to over one hundred feet in circumference, at the ground, and in almost every position and condition, would become almost bewildering were I to present in detail each and every one; a few notable examples therefore, will suffice, as representatives of the whole.

The first big tree that attracts our attention, and which is seen from the ridge north of the Stanislaus River, is the “Columbus,” a magnificent specimen, with three main divisions in its branches; and standing alone. Passing this we soon enter the lower end of the South Grove, and arrive at the “New York,” one hundred and four feet in circumference, and over three hundred feet in height. Near to this is the “Correspondent,” a tree of stately proportions, named in honor of the “Knights of the Quill.” The “Ohio” measures one hundred and three feet, and is three hundred and eleven feet in height. The “Massachusetts” is ninety-eight feet, with an altitude of three hundred and seven.

Near to a large black stump, above this, stands a tree that is seventy-six feet in circumference, that has been struck by lightning, one hundred and seventy feet from its base; where its top was shivered into fragments, and hurled in all directions for over a hundred feet from the tree; the main stem being rent from top to bottom, the apex of this dismantled trunk being twelve feet in diameter. The “Grand Hotel” is burned out so badly that nothing but a mere shell is left. This will hold forty persons. Then comes the “Canal Boat”; which, as its name implies, is a prostrate tree; the upper side and heart of which have been burned away, so that the remaining portion resembles a huge boat; in the bottom of which thousands of young big trees have started out in life; and, if no accident befalls them, in a thousand or two years hence, they may be respectable-sized trees, that can worthily take the places of the present representatives of this noble genus, and, like these, challenge the admiring awe of the intellectual giants of that day and age.

“Noah’s Ark” was another prostrate shell that was hollow for one hundred and fifty feet; through which, for sixty feet, three horsemen could ride abreast; but the snows of recent winters have broken in its roof, and blocked all further passage down it. Next comes the “’Tree of Refuge,” where, during one severe winter, sixteen cattle took shelter; but subsequently perished from starvation. They found protection from the storm, but their bleaching bones told the sad tale of their sufferings and death from lack of food. Near to this lies “Old Goliath,” the largest decumbent tree in the grove; whose circumference was over one hundred feet, and, when erect, was of proportionate height to the tallest. During the gale that prostrated “Hercules,” in the Calaveras Grove, this grand old tree had also to succumb. One of his stalwart limbs was eleven feet in diameter.

There is another notable specimen, which somewhat forms a sequel to the above, known as

|

| Photo by J. C. Scripture. |

| SMITH’S CABIN. |

“Adam” and “Eve” we did not see, but were assured that the former has a circumference of one hundred and three feet; and that the latter was a fitting helpmate to Adam, at least in correlative magnitude, with breast-like protuberances seven feet in diameter, at an altitude of one hundred and fifty feet from the ground.

Before taking leave of the South Grove, it may be well to mention, that it is three and a half miles in length, situated in a beautifully formed, valley-like hollow, that not only contain the number of “big trees” already mentioned, but, like the Calaveras Grove, has magnificent colonnades of other trees, such as the sugar pine (Pinus Lambertiana); the two yellow pines (Pinus ponderosa and P. Jeffreyi); three silver firs (Abies concolor, A. grandis and A. nobilis); the red spruce (A. Douglasi); the cedar (Libocedrus decurrens), with other genera; and an almost endless variety of beautiful shrubs and flowers. Indeed, there is a richly supplied banquet, as endless in variety as it is unique in loveliness and grandeur, upon which appreciative minds can feast the whole of the ride. Upon the return a glimpse can be had, westwardly, of the Basaltic Cliff; and which forms the destination of one of the many enjoyable rides from the hotel.

As we must soon bid a pleasant adieu to the Calaveras Groves, before saying our parting “good-by,” it may be well to state that the “Calaveras” and “South Groves” are both owned by Mr. James L. Sperry, who is also the proprietor and landlord of the Calaveras Grove Hotel;’ and who has the good fortune of uniting the attentive considerations of “mine host,” with the intuitive qualities of a gentleman—not always met with when traveling. And, for the information of the public, I most unreservedly state that here will be found a good table, cleanly accommodations, polite service, and reasonable charges; to which I deem it my duty to add, that the air is pure and invigorating; the climate exhilarating and renewing; and the trout-fishing in adjacent streams most excellent. Months should be spent here instead of a few brief hours, or days.

Now, if you please, in the quiet of the evening, we will return to Murphy’s; and, after we have had a good dinner, and a brief rest, will visit

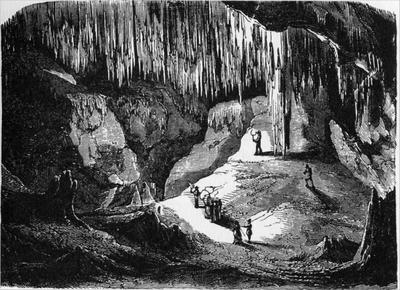

This, believe me, is one of the greatest natural curiosities of this section. It is situated about a mile from town, and can be reached either by carriage or afoot; and, moreover, can be seen as well by night as by day.

The moment it is entered, intense darkness envelops you like a mantle; so that even the candles, carried by visitors, seem barely sufficient to more than “make darkness visible.” Soon, however, the eyes become adjusted to the circumstances, and objects become more or less recognized, although indistinctly at first, then to reveal themselves more clearly to our astonished gaze.

The first chamber reached is about two hundred feet from side to side, its roof stretching far upward into semi-darkness some seventy or eighty feet; and, like the side wall, is slightly curvilinear in form, and at an angle of about 50°. Its uneven sides are partially covered with grotesquely formed stalactites, in masses, closely resembling white fungus. Some hang pendent, like icicles that have run into each other, and broadened as they formed; yet are suspended, in some instances, by a slender, tape-like stem, that one would expect to be broken almost by a breath. From among the seams of the rock overhead hang slender bunches of dark chocolate-colored moss, that are from ten to sixteen feet in length.

Proceeding downwards, the sides of the chamber resemble the folds of massive curtains, the edges or binding of which are, in appearance, very closely akin to the delicate white coral of the South Seas. Here and there are stalagmites that appear like inverted icicles, somewhat discolored, from a few inches to over seven feet in height, and from three inches to two feet in diameter. In one spot stand “The Cherubim,” united by a ligature like the once celebrated Siamese Twins. These are about three feet in width by four in height, white as alabaster, and glistening with frost-like crystals.

Still descending, one threads his way among narrow corridors and chambers, the walls of which are draped with coral-like ornaments of many beautiful patterns, until he reaches “The Angels’ Wings.” These are some eight feet in length by three in breadth, while not exceeding half an inch in thickness, and which are seemingly cemented to the nearly vertical wall of the chamber. From top to bottom of these “wings,” are numerous irregular bands, about one and a half inches broad, and of various tints of pink; which show to great advantage when a light is placed at the back of these translucent, wavy sheets. When gently touched—and they should be gently touched, if at all—they give forth sweetly musical notes that resound weirdly through those silent halls of darkness. Nature, as though intending the protection of these delicate forms from vandal hands, has surrounded them with stone icicles.

Other portions of the walls, especially near the roof-ceiling (if so it may be called), have the appearance of an inverted forest of young pines, that, having been dwarfed in their growth, were afterwards turned into stone. Still others resemble moss, lichens, or dead trees in miniature. Occasionally the entire side wall has a resemblance to sugar frosting, which is sufficiently delusive to the eye for tempting children to wish for a piece of it to eat!

The lowest chamber, two hundred and twenty-six feet below the entrance, is the most singular and beautiful of all. If imagination for a moment could come to our assistance, and picture the most exquisitely delicate of coral, arranged in beautiful tufts, and masses, the entire surface covered with silvery hoar frost, and that surface extending up a wall over thirty feet in height, we could obtain some approximating idea of this gorgeous spectacle. There is no language that can approximately portray this fairy-like creation of some chemical genii for the simple reason that it is utterly indescribable.

Specimens of human remains, and those of other animals, have been exhumed from this cave, some of which were embedded on the alabaster formation.

Exists seven miles north of Murphy’s, and which is probably in the same belt of limestone. This is on “McKinney’s Humbug Creek” (what a name!), a tributary of the Calaveras River. As you enter, the walls are dark, rough, and solid, rather than beautiful; but you are soon ushered into a chamber, the roof of which is for some time invisible in the darkness, but where the whole formation has a resemblance to a vast cataract of waters, rushing from some inconceivable height in one broad sheet of foam.

Descending through a small opening, we enter a room beautifully ornamented with pendants from the roof, white as the whitest feldspar, and of every possible form. Some, like garments hung in a wardrobe, every fold and seam complete; others, like curtains; with portions of columns, half-way to the floor, fluted and scalloped for unknown purposes; while innumerable spear-shaped stalactites, of different sizes and lengths, hang from all parts, giving a beauty and splendor to the whole appearance

|

| VIEW OF THE BRIDAL CHAMBER. |

Immediately at the back of this, and yet connected with it by different openings, is another room that has been, not inappropriately, named “The Music Hall.” On one side of this is suspended a singular mass, that resembles a musical sounding-board, from which hang numerous stalactites, arranged on a graduated scale like the pipes of an organ; and if these are gently touched by a skilled musician’s hand, will bring out the sweetest and richest of notes, from deep bass to high treble.

If time would permit, it would repay us, before leaving Murphy’s, to visit the productive gold mines of Central Hill and Oro Plata; see the deep excavations made between the fissure-like formations of the limestone here, for the purpose of extracting the gravel therefrom, which contains the precious metal; or, to watch the various processes used in separating the gold from the gravel and pay dirt; but, as the stage leaves at 7 o’clock a. m., this will be impossible, unless we decide to remain behind for a day or two for that purpose.

It may be interesting for the stranger to know that after leaving Murphy’s, our course, for nearly thirty miles, is substantially over the bed of an ancient river, that once ran parallel with the main chain of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. There is no telling how much this stream could reveal to us if it had the power, inasmuch as the fossil remains of mastodons, mammoths, and other animals have been found here. The late Dr. Snell, of Sonora,had several hundred specimens of these. Then, gold in fabulous quantities has been taken from among the bowlders and gravel forming the under-stratum of this stream. In 1853 the writer saw a nugget of solid gold extracted near Vallecito, four miles from Murphy’s, that was shaped like a beef’s kidney, and weighed twenty-six pounds.

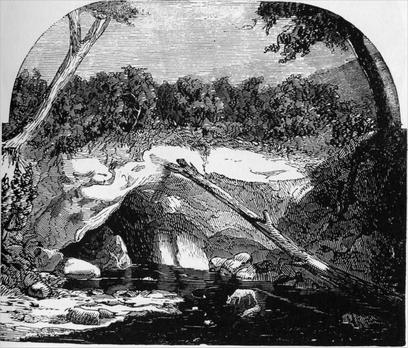

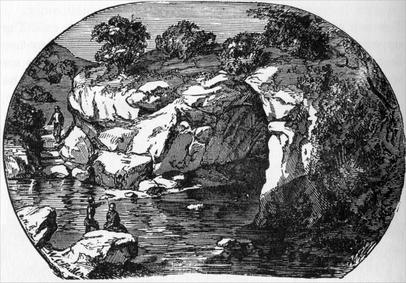

But soon after leaving Vallecito, our course winds down among the hills to Cayote Creek, upon which, about five hundred yards below the road, are two

Beneath which all the waters of the creek make their exit. The upper side of the upper natural bridge to its arch is thirty-two feet, and the breadth of the arch, twenty-five feet; but as we walk beneath it, the height increases to fifty feet, and the

|

| THE UPPER SIDE OF UPPER NATURAL BRIDGE. |

About half a mile below the lower side of the upper bridge,

|

| THE UPPER SIDE OF LOWER NATURAL BRIDGE. |

Soon we reach Parrot’s Ferry at the Stanislaus River, where we find a kindly-hearted old hermit, after whom the ferry is named, who takes us safely across. This stream, transversely crossing the general trend of the ancient river, has cut the old bed away, and formed a channel through it nearly one thousand feet in depth; but, when we have ascended the hill, we are again upon its course.

The auriferous treasures that were there found, stimulated the effort and rewarded the energy of many thousands of miners, and the thriving settlements of Gold Spring (a bounteous spring having here supplied water for washing out the gold), Columbia, Springfield (where another spring gushes out), Shaws Flat, Sonora, Jamestown, and others sprang into life. It is no exaggeration to say that, within a radius of eight miles, not less than ten thousand miners found employment in unearthing the precious metal, from 1849 to 1854. And although it was supposed by many that these diggings were long since “all worked out,” a population still numbering thousands obtains profitable returns from it, directly or indirectly. But while we have been talking, we find ourselves passing down the main street of one of the prettiest mining towns in California, euphoniously named

I like Sonora, and like and believe in its wide-awake, energetic, and large-hearted people; with whom I frankly confess to feel most thoroughly at home. And if time only permitted, I should desire to introduce them, personally; knowing that you would be gratified and honored with their acquaintance. As this, however, is impracticable, I cannot forego the opportunity of saying, that Sonora is not only the county seat of Tuolumne County, but is still the center of a rich mining district. Only a few years ago the “Piety Hill” ledge (since named the “Bonanza Mine”), alone, yielded over half a ton of gold in a single week; and this is only one of many claims still profitably worked. Wood’s Creek, upon which Sonora and other towns are located, has produced more gold, for its length, than almost any other stream on the Pacific Coast; and it is questionable if any mule team in existence could haul away in a single load all the precious metal that has been taken from these rich mines. Nor is gold the only product, by any means; inasmuch as the very finest of fruit, and that in untold abundance, is grown here; with all kinds of vegetables, and cereals. Its altitude, as given by the Wheeler U. S. Survey, is, at the post-office, one thousand eight hundred and sixteen feet above sea level.

As the climate is temperate, healthy, and exceedingly invigorating; its people kindly-natured and enterprising; the gold mines and mining interests instructive to the student, and diverting to the invalid, with abundant educational advantages provided for the young, there can exist but little doubt that the entire section, in and around Sonora, at a very early day, will become not only a favorite place to visit, but whereon to found permanent homes.

A few miles above Sonora, upon or near the great highway which here crosses the main chain of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, are several very productive gold-bearing quartz ledges, that give profitable employment to hundreds of men, and yield rich returns of the precious metal to their fortunate owners.

Upon our departure from this prosperous town, we follow the course of Wood’s Creek, past suburban residences and gardens, machine shops and foundries, flouring mills and quartz mills, orchards and vineyards; down to the once famous mining camp of Jamestown (affectionately called by old residents “Jimtown"—consult Bret Harte and Prentice Mulford on this); and as we now drive through its principal street, and revert to its exciting past, it requires quite an effort to overcome the sadness which the contrast inspires, and which, uninvitedly, prompts the soliloquy, sic transit gloria mundi. Still, there is more or less prosperity lingering here, owing to its proximity to the gold mines of Poverty Hill, Quartz Mountain, and others. From Jamestown, through Montezuma, to Chinese Camp, evidences are abundant that this extensive district was once thronged to overflowing with miners, and full to the brim with mining life. But as we are now in Chinese Camp, and our route here intersects with the Milton and Big Oak Flat, our course hence will be outlined in a future chapter.

Next: Chapter 17 • Index • Previous: Chapter 15

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/16.html