| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Half Dome & Cloud’s Rest >

Next: Chapter 27 • Index • Previous: Chapter 25

|

The broad blue mountains lift their brows

Barely to bathe them in the blaze.

—Harriet Prescott Spofford’s

Daybreak.

|

|

He prov’d the best man i’the field; and for his meed

Was brow-bound with the oak.

—Shakespear’s

Coriolanus, Act II, Sc. 2.

|

|

Round its breast the rolling clouds are spread,

Eternal sunshine settles on his head.

—

Goldsmith’s

Deserted Village.

|

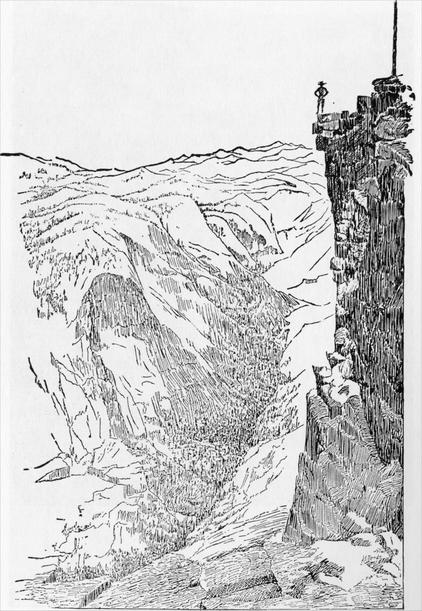

When standing on the bare granite in front of Snow’s Hotel, with the Nevada Fall and Cap of Liberty at our backs, not only are the Silver Apron, Emerald Pool, and Glacier Point (including McCauley’s House) distinctly visible before us; but, looking northwestwardly, there towers up the bold, rugged point of a mountain, and one that has also attracted considerable attention from us when in the Valley, that, at its base, is skirted by the Anderson Trail, and which is known as

Seen from this standpoint it resembles an immense Moorish head, with a long, prominent nose, formed of one large slab of rock set edgewise, with dwarf trees for eyebrows. This, and the Cathedral Spires, are the only points upon which I have never set foot. Mr. Chas. A. Bailey climbed this a year ago, and has kindly sent me the following account of his difficult feat:—

Stimulated by the assertion that Grizzly Peak had never been ascended by any white man, I determined to attempt it. Leaving Snow’s with a stout staff and a good lunch, I crept up a narrow and steep ravine, flanked by the great Half Dome, to a narrow connecting neck between the latter and the object of my ambitious climb. This was attended by many a rough scramble, as its nearly vertical sides loomed up like a church steeple. Crossing the neck to its southerly side, there was but one spot that was possibly accessible, and this was made so only by the aid of friendly bushes that grew in the interstices of the rock. An unbroken precipice extended from the edge of the peak to the Valley on one side, but which developed a slab-cleavage of granite on the other, the edge of which, although sharp, was rapidly disintegrating; but this I mounted, and, by striding, clasping, hitching, and crawling along it, reached its farther and upper end in safety.

Further on the ascent had to be made by climbing up a narrow fissure, by pressing my knees and elbows against its sides, until either finger or foothold could be obtained. This passed, a steeply slanting rock was crossed by moving over it with a crawling kind of motion, where friction and the force of gravitation were my principal helpers, to keep me from sliding over the cliff. As a safeguard, however, I kept my eye on some projecting slabs below, for which I intended to spring, should I unavoidably slide from my position. Fortunately I eventually reached the top, some two thousand five hundred feet above the Valley, in safety.

The glories of these crags seem to be immeasurably heightened and deepened, and the uplifting peaks made grander and loftier, when their summits are attained by a hard and perilous climb; and the view from Grizzly Peak was so unlike that I had obtained elsewhere, that the very novelty charmed and repaid me. Resting, as it apparently does, in the shadow of the great Half Dome; on the edge, and almost projecting over the Merced River, its position is commandingly impressive. Glacier Point, though seemingly near, with a much greater altitude, has a wonderfully imposing presence from this standpoint. Looking east and south, Mt. Broderick (the peak next westerly from the Cap of Liberty), Mt. Clark, and Mt. Starr King, stand grandly out above their lesser mountain brethren. From here, too, a bird’s-eye view is obtained of Snow’s, which, with its surrounding trees, and the Emerald Pool, looks like a place of enchantment. Perhaps the finest single view of all these is the Too-lool-a-we-ack, or Glacier Cañon, which can be seen for its entire length; with its narrow mountain-walled channel, its numberless bowlders, its dashing and foaming torrent, and its distant water-fall of some four hundred feet at the end. I fondly hoped to get a view of the upper falls; this, however, was intercepted by a jutting spur. But for this I could have seen the four great water-falls of the Valley from a single standpoint—the Vernal, Nevada, Too-lool-a-we-ack, and Yo Semite—a spectacle that would have been unparalleled. The first ascent of Grizzly Peak accomplished, I left my card, and water bottle, as mementos of my visit.

|

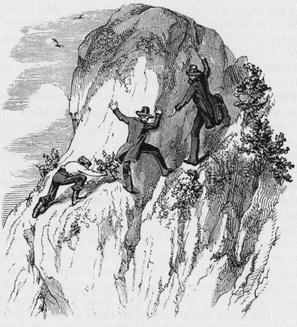

| AN “INDIAN ESCAPE TRAIL." |

|

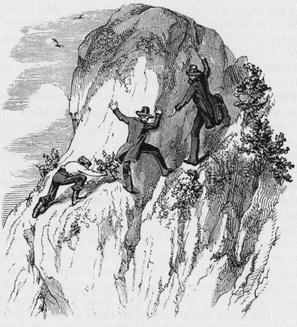

| ASCENDING THE LOWER DOME. |

Seven years after this an athletic youth informed the writer that he was “going to climb to the top of the Half Dome.” I quietly suggested that such a feat was among the doubtful things of this life. He was willing to bet any amount that he could accomplish it. I informed him that I was not a betting man,—had never made a bet in my life, and was too old to begin now,—but, if he would put a flag upon the only visible pine tree standing there, I would make him a present of twenty dollars, and treat him and his friends to the best champagne dinner that could be provided in Yo Semite. Three days after this he walked past without deigning to stop, or even to look at us,—and there was no flag floating from the top of the Half Dome either!

This honor was reserved for a brave young Scotchman, a native of Montrose, named George G. Anderson, who, by dint of pluck, skill, unswerving perseverance, and personal daring, climbed to its summit; and was the first that ever successfully scaled it. This was accomplished at 3 o’clock p. m. of October 12, 1875.

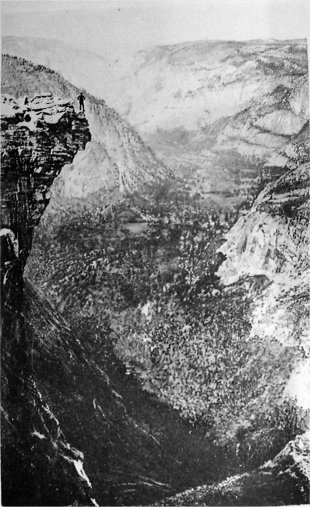

| |

| Photo by S. C. Walker. | Photo-typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| The Half or South Dome—Tis-sa-ack. | |

| A precipice of 5,000 Feet, with Geo. Anderson Standing on it. | |

| (See page 460.) | |

The knowledge that the feat of climbing this grand mountain had on several occasions been attempted, but never with success, begat in him an irrepressible determination to succeed in such an enterprise. Imbued with this incentive, he made his way to its base; and, looking up its smooth and steeply inclined surface, at once set about the difficult exploit. Finding that he could not keep from sliding with his boots on, he tried it in his stocking feet; but as this did not secure a triumph, he tried it barefooted, and still was unsuccessful. Then he tied sacking upon his feet and legs, but as these did not secure the desired object, he covered it with pitch, obtained from pine trees near; and although this enabled him to adhere firmly to the smooth granite, and effectually prevented him from slipping, a new difficulty presented itself in the great effort required to unstick himself; and which came near proving fatal several times.

Mortified by the failure of all his plans hitherto, yet in no way discouraged, he procured drills and a hammer, with some iron eye-bolts, and drilled a hole in the solid rock; into this he drove a wooden pin, and then an eye-bolt; and after fastening a rope to the bolt, pulled himself up until he could stand upon it; and thence continued that process until he had finally gained the top—a distance of nine hundred and seventy-five feet! All honor, then, to the intrepid and skillful mountaineer, Geo. G. Anderson, who, defying and overcoming all obstacles, and at the peril of his life, accomplished that in which all others had signally failed; and thus became the first to plant his foot upon the exalted crown of the great Half Dome.

His next efforts were directed towards placing and securely fastening a good soft rope to the eye-bolts, so that others could climb up and enjoy the inimitable view, and one that has not its counterpart on earth. Four English gentlemen, then sojourning in the Valley, learning of Mr. Anderson’s feat, were induced to follow his intrepid example. A day or two afterwards, Miss S. L. Dutcher,’ of San Francisco, with the courage of a heroine, accomplished it; and was the first lady that ever stood upon it. In July, 1876, Miss L. E. Pershing, of Pittsburgh, Pa., the writer, and three others found their way there. In October following, six persons, among them a lady in her sixty-fifth year, and a young girl, thirteen years of age (a daughter of the writer), and two other ladies, climbed it with but little difficulty, after Anderson had provided the way. Since then very many others have daringly pulled themselves up; and enjoyed the exceptionally impressive view obtained thence.

The summit of this glorious mountain contains over ten acres, where persons can securely walk, or even drive a carriage, could such be transported thither. There are seven pine trees upon it, of the following species: Pinus Jeffreyi, R monticola, and R contorta; besides numerous shrubs, grasses and flowers. A “chip-monk,” some lizards, and grasshoppers, have taken up their isolated preŽmption claims there. Two sheep, supposed to have been frightened by bears, once scrambled up there; to which Mr. Anderson daily carried water, until they were eventually lost sight of Their bones were afterwards discovered side by side, in a sheltered hollow.

The commanding position of the Half (or South) Dome at the head of the Valley, with a vertical altitude above it of nearly five thousand feet, two-thirds of which is absolutely in the zenith, makes the vies from its culminating crest inexpressibly sublime. There is not only the awe-inspiring depth into which one can look, where everything is dwarfed into utter insignificance, but the comprehensive panorama of great mountains everywhere encompassing us. As Yo Semite, confessedly, has not its emulative counterpart on earth, so is this view the culminating crown of scenic grandeur, that is utterly without a rival upon earth.

When sitting upon its edge our feet swing over a vortex of five thousand feet; and if we can imagine forty-five San Francisco Palace Hotels placed on top of each other, and ourselves seated upon the cornice of the upper one, surrounded by mountain peaks, deep gorges, beautiful lakes, and vast stretches of forest, with here and there bright pastures, some realizing sense of the preŽminently glorious scene may partially be conceived.

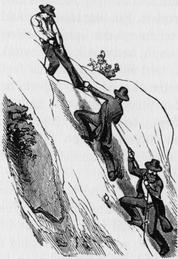

| |

| Photo by S. C. Walker. | Photo-typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| ANDERSON ON PRECIPICE OF HALF-DOME—5,000 FEET. | |

| (Looking East up Ten-ie-ya Cañon.) | |

Such a position, to those whose nerves had not been disciplined, might be trying in the extreme, if not impossible; but to those whose daily life brings them in constant and familiar con tact with such, there is no perceptible nervousness whatsoever; therefore there is no particular merit in it. In 1877 Mr. Anderson, after assisting Mr. S. C. Walker, the photographer, and the writer, to pack up all the photographic apparatus necessary for taking views from its summit, deliberately placed upon a large flat rock, projectingly, on the margin of the precipice, and stood upright upon it while the photograph was taken; one of his feet being over, and beyond the edge eleven inches, as presented in the accompanying view, taken at that time. Although unsteadied and unsupported, not a nerve or muscle quivered.

About seventy feet from the face of the Half Dome wall, there is a narrow and nearly vertical fissure, several hundred feet in depth judging from the time stones dropped in were traveling to the bottom. This becomes suggestive that ere very long a new fracture may here take place.

During the severe winter of 1883-84 the ice and snow sliding down the smooth back of the great Half Dome, carried with it over four hundred feet of the rope Anderson had put up with so much care and risk, and several of the iron eye-bolts with it. This deprived every enthusiastic climber of the pleasure of ascending to its wondrous summit, and of obtaining the unequalled view from that glorious standpoint. No one seemed imbued with sufficient ambitious courage to replace it—Anderson having passed away to his rest.

But, just after sunset, one evening of the ensuing summer, every resident of the Valley, familiar with the fact of the rope’s removal, was startled by the sight of a blazing fire upon its utmost crest; and all kinds of suppositious theories were indulged in concerning such phenomena. No one knew of any one contemplating so hazardous a venture. What could it mean? Eventually it transpired that two young gentlemen, who were summering in the Sierras, hunting, fishing, reading, and sketching, had been missed some days from their camping-ground in the Valley; and, therefore, there was the possibility that these might have unknowingly attempted to ascend it, and succeeded. But that possibility shared the companionship of another, which filled every mind with consternation; that they were up there, and could not come down; that the fire seen was at once a signal of distress as well as of success, and a call for help.

Before daylight the following morning, therefore, four of us, well supplied with ropes, extra bolts, and other essentials, were upon the way for their deliverance. At Snows, however, we met the daring adventurers; and found that, although they had made the perilous climb up, they had also accomplished the descent in perfect safety. These twin heroes were Mr. Alden Sampson, of New York City, and Mr. A. P Proctor, of Colorado.

Grateful for the intended, though unneeded deliverance, these young gentlemen very thoughtfully presented themselves at the cabin, to tender their thanks, and express their acknowledgments of the good services premeditated; when Mr. Sampson kindly favored me with the following recitative of their danger-defying exploit:—

Our challenge, if I may so call it, to make the ascent, came with the first inspiring sight of the Valley and of the Half Dome beyond. We were traveling in the saddle, with pack-animals, camping whenever the outlook was finest, or when we could find grazing or a night’s feed at some ranch for our stock. From Wawona, we had come in by the Glacier Point trail, and had pitched camp for the night at Glacier Point. Here we had the good fortune to meet Mr. Galen Clark, one of the pioneers of the Valley, and in answer to our inquiries as to the view from the Half Dome, which was the most prominent feature of the landscape, were told that there had formerly been a rope to the summit, put up by Anderson, but that it was down, and would probably so remain until some venturesome member of the English Alpine Club should come along and have the goodness to replace it. This aspect of the matter, I must own, galled our pride; and the more we thought it over the less we liked this solution of the difficulty. Should we, forsooth, wait for foreign sinew to scale for us a peak of the American Sierras? Not if it lay in our power to prevent so humiliating a favor! But we did not by any means decide then that we would make the ascent; when we had at last made up our minds to do so, we quietly reconnoitered the place, and made all necessary preparations in entire secrecy, so that no one should have the satisfaction of laughing at us if we failed. Then taking two hundred feet of picket rope, a handful of lunch, and a lemon apiece, in the early morning we rode from our camp in the Little Yo Semite to the base of the dome.

Fortunately, in making this ascent, my companion and myself supplemented one another’s work. He would throw the reata like a native Californian, so that when a pin was not thirty feet off, he would be sure to “rope it” the first cast. The end of the reata once fast, one of us would pull himself up by it, then stand upon the pin, ready to take up and make fast the old rope, when the other had tied the lower end of the reata to it. But after a while we came to a clean stretch of a hundred feet, where every pin had been carried away; yet, at this point a difficult corner of the ledge had to be turned. My companion, being barefooted, found that he could not cling to the surface as well as I could, with hob nails under my feet, so I had the pleasure of attempting this all to myself. The sensation was glorious. I did not stake my life upon it, for I was sure I could make it. If I had slipped in the least I should have had a nasty fall of several hundred feet. To be sure, I was playing out a rope behind me attached to my waist, but supposing I had fallen, with all this slack below me, my weight would have snapped it, or the rope would have cut me in two. The difficult part here was that a point had to be rounded on naked granite, that was both steep and slippery; not the coarse, rough variety that one sometimes sees, but polished by beating Sierra storms, and the snow-slides of innumerable winters. In the hardest place of all, a little bunch of dwarf Spirea, six or eight inches high, which was growing in a crevice, gave me friendly assistance. What it lived on up there I cannot imagine, as it grew in such a narrow crack of the ledge. However, its roots had a tenacious hold; and a piece of partially rotten bale rope afforded me a pull of ten or twelve pounds, quite enough to steady one at the most dangerous moment.

My companion exercised great skill and patience in making throws with the reata, often having to sit on the edge of a seemingly perpendicular precipice, morally supported, to be sure, by a rope from his waist, attached to the pin below him, but for actual physical support relying solely upon his foothold on the iron eyebolt under his feet. I dare say that his experience in one thing was similar to my own,—the feeling that when he clung to the face of the rock it was seemingly trying to push him off from it. We succeeded in putting up about half the rope the first day, and spent the night at our camp below. In the afternoon of the second day we came to a long, smooth stretch, without eyebolts or anything to offer assistance, not as steep as we had encountered, but very slippery. After many unsuccessful attempts to lasso the first pin a hundred feet away, with such precarious foothold as we had, nearly two precious hours were consumed, and the task was apparently hopeless, which would have given us another rather dangerous climb without any assistance whatever to rely upon; at last by a fortunate cast the reata caught the distant pin firmly, and as we made it taut, we could not repress a shout of joyful exultation, for the enemy was now conquered and the remainder of the ascent could be made with ease. We were soon upon the summit, signaling those that we thought might possibly be watching us from below.

As intimated elsewhere, there is a singular appropriateness in the name of this grand mountain crest, inasmuch as there is frequently a cloud lingering there when there is not another visible in the firmament. Seen from the Valley it is always a point of attractive interest especially when wreathed in storm. It is about one thousand feet higher than the Half Dome; its height being six thousand feet above the Valley.

From its cloud-crested top one vast panorama of the High Sierra, embracing an area over fifty miles in length, is opened at our feet. Nestling valleys, pine-margined lakes, bleak mountain peaks, lonely and desolate, and deep gorges half filled with snow, are on every hand. To the eastward, above the timber line, (here about 10,800 feet high), stands boldly out Mt. Hoffmann, 10,872 feet above sea level; Mt. Tuolumne, 11,000 feet; Mt. Gibbs, 13,090 feet; Mt. Dana, 13,270 feet; Mt. Lyell, 13,220 feet; Echo Peak, 11,231 feet; Temple Peak, 11,250 feet; Cathedral Peak, 11,200 feet; Mt. Clark (formerly known as Gothic Peak, the Obelisk, etc.), 11,295 feet; Mt. Starr King, 9,105 feet, with numerous others that are as yet nameless; while the point upon which we are supposed to be standing (Cloud’s Rest) is 9,855 feet.

Turning our eyes westward, we look down upon the crown of the Half Dome, and the great Valley below. But who can paint the haze-clothed heights, and depths, of the wonderful scenes before us? Almost at our feet, 6,000 feet beneath us, sleeps Mirror Lake; yonder, the North Dome, the Yo Semite Fall, Eagle Peak, El Capitan, Sentinel Dome, Glacier Point, and many others that margin the glorious Yo Semite. Verily this view must be seen to be even partially realized.

The way to these wondrous scenes is past the base of the Cap of Liberty, up a somewhat steep ascent; at the right of which a splendid side view of the Nevada Fall is obtained. At the top of the “zigzags” the horses should be tied, and a tramp taken of about two hundred yards to

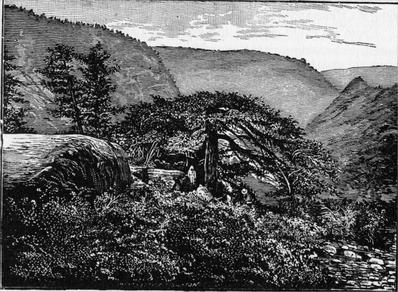

Here the Merced River, for some distance, forms a series of rapids, near the edge of which are numerous patches of bare, glacier-polished granite. Leaving these on our left, we seek the edge of the cliff, over which the Nevada is making its marvelous leap. On the way we see a singular botanical freak of nature, known as

|

| The Umbrella Tree. |

It is a Douglas spruce, Pseudo tsuga Douglasii. Just beyond this we can stand on the edge of the precipice; but, as it is flat, nearly all lie down to take a soul-filling glimpse of the awe-inspiring majesty and glory beneath. The fall, almost directly after it daringly leaps its rocky rim, strikes the inclining wall, and apparently forms into a wavy mass of curtain-like folds, composed from top to bottom of diamond lace; now draping this side, then lifted, as by fairy hands, to the other. The base, as though it would make the whole scene a miniature heaven, and through it lead men to the outer footstool of the Almighty throne, is spanned with gorgeous rainbows; while the beautiful river hurries on, and the grand mountains around stand sentinel forever.

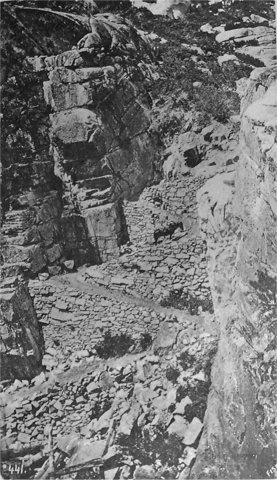

| |

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| Zigzags to Top of Nevada Fall. | |

| (See page 463.) | |

About a mile beyond we enter the Little Yo Semite Valley, at the head of which, some three miles distant, is a sugar-loaf shaped mountain, and a cascade one hundred and fifty feet in length, down which the Merced River rushes at an angle of about 20% Just beyond this a bold bluff, a thousand feet in height above the river, juts across the entire upper end, the top of which is highly polished by glaciers; and around it every hollow is filled with the detritus of old moraines.

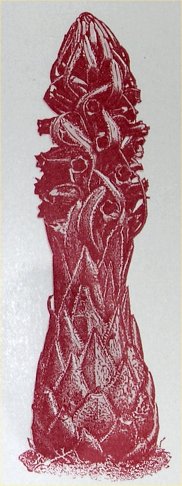

The picturesque Little Yo Semite left behind, with its glacier-polished mountains around it, our course hence, to both Half Dome and Cloud’s Rest, is, for the most part, over old moraines, where bowlders from every conceivable texture of granite, totally unlike that which forms the base here, are strewn on every hand. Those who have entertained a doubt about ancient glaciers having once covered the whole broad field of the Sierras, can here find evidence beyond question to dispel it. As we journey upward and onward, new mountain peaks and spurs and ranges come into view; while flowers of every hue bloom at our side. The one most conspicuous of all, however, is

THE SNOW PLANT OF THE SIERRAS (Sarcodes sanguinea).

This blood-red and strikingly attractive flower is to be seen upon every route to the Big Trees and Yo Semite Valley, as upon nearly every trail or by-path in or around them, at an elevation above sea level, ranging from four to eight thousand feet; its brilliant, semi-translucent stem, and bells, and leaves that intertwine among the bells, being all blood-red, their constituents seemingly of partially crystallized sugar, make it the most conspicuously beautiful flower born of the Sierras.

From the common name it bears might come the impression that its birthplace is among the Sierran snows, but this is not the case; for, although its growth and early development is beneath deep banks of snow, it seldom shows its blood-red crown until some days after the snow has melted away.

Many eminent botanists consider this a parasitic plant, some affirming that it grows only upon a cedar root (Libocedrus decurrens) in a certain stage of decay; but these deductions may have been made from the close resemblance in outline of the Sarcodes sanguinea with the Boschniakia strobilacea, which is positively a parasitic flower, that prefers the manzanita as its host. I have, however, seen this floral gem flourishing over a thousand feet above the habitat of cedars; and, after carefully digging up over twenty specimens, could find no indication whatever of their parasitic character.

The height of its panicled blossom above ground is from seven to sixteen inches, with a diameter of from two to four inches; its bulb-root extending as far down into the earth as the flower is above it. When digging up specimens, therefore, this fact should be remembered; as to break them off—and they are exceedingly brittle—is to spoil them.

|

On those eternal peaks where winter reigns,

—Sarah J. Pettinos. |

|

| The California Snow Plant

(Sarcodes sanguinea.) One-Third Natural Size. |

Next: Chapter 27 • Index • Previous: Chapter 25

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/26.html