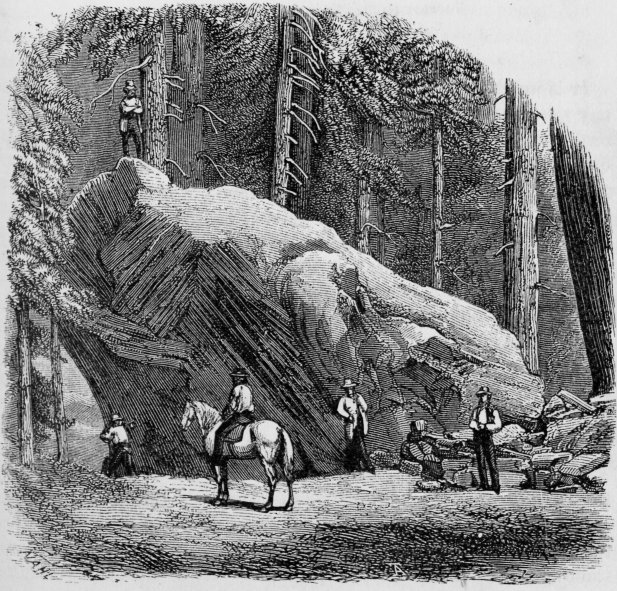

BUTT AND SECTION OF THE MAMMOTH TREE TRUNK.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Scenes of Wonder & Curiosity > The Mammoth Trees of Calaveras >

Next: Calaveras Caves • Contents • Previous: Illustrations

BUTT AND SECTION OF THE MAMMOTH TREE TRUNK. |

|

“God of the forest’s solemn shade!

Peabody. |

It is much to be questioned if the discovery of any wonder, in any part of the world, has ever elicited as much general interest, or created so strong a tax upon the credulity of mankind, as the discovery of the mammoth trees of California. Indeed, those who first mentioned the fact of their existence, whether by word of mouth or by letter, were looked upon as near, very near, relatives of Baron Munchausen, Captain Gulliver, or the celebrated Don Quixote. The statement had many times to be repeated, and well corroborated, before it could be received as true; and there are many persons who, to this very day, look upon it as as a somewhat doubtful “California story;” such, we never expect to convince of the realities we are about to illustrate and describe, although we do so from our own personal knowledge and observation.

In the Spring of 1852, Mr. A. T. Dowd, a hunter, was employed by the Union Water Company, of Murphy’s Camp, Calaveras county, to supply the workmen engaged in the construction of their canal, with fresh meat, from the large quantities of game running wild on the upper portion of their works. Having wounded a bear, and while industriously following in pursuit, he suddenly came upon one of those immense trees, that have since become so justly celebrated throughout the civilized world. All thoughts of hunting were absorbed and lost in the wonder and surprise inspired by the scene. “Surely,” he mused, “this must be some curiously delusive dream!” but the great realities standing there before him, were convincing proof, beyond a doubt, that they were no mere fanciful creations of his imagination.

When he returned to camp, and there related the wonders he had seen, his companions laughed at him and doubted his veracity, which previously they had considered to be very reliable. He affirmed his statement to be true, but they still thought it “too much of a story” to believe—thinking that he was trying to perpetrate upon them some first of April joke.

For a day or two he allowed the matter to rest—submitting, with chuckling satisfaction, to the occasional jocular allusions to “ his big tree yarn,” and continued his hunting as formerly. On the Sunday morning following, he went out early as usual, and returned in haste, evidently excited by settle event. “Boys,” he exclaimed, “I have killed the largest grizzly bear that I ever saw in my life. While I am getting a little something to eat, you make preparations to bring him in. All had better go that can possibly be spared, as their assistance will certainly be needed.”

As the big tree story was now almost forgotten, or by common consent laid aside as a subject of conversation; and, moreover, as Sunday was a leisure day—and one that generally hangs the heaviest of the seven on those who are shut out from social intercourse with friends, as many, many Californians unfortunately are—the tidings were gladly welcomed; especially as the proposition was suggestive of a day’s excitement.

Nothing loath, they were soon ready for the start. The camp was almost deserted. On, on they hurried, with Dowd as their guide, through thickets and pine groves; crossing ridges and cañons, flats and ravines; each relating in turn the adventures experienced, or heard of from companions, with grizzly bears and other formidable tenants of the forests and wilds of the mountains; until their leader came to a dead halt at the foot of the tree he had seen, and to them had related the size. Pointing to the immense trunk and lofty top, he cried out, “Boys, do you now believe my big tree story? That is the large grizzly I wanted you to see. Do you still think it a yarn?”

Thus convinced, their doubts were charged to amazement, and their conversation from bears to trees; afterward confessing that, although they had been caught by a ruse of their leader, they were abundantly rewarded by the gratifying sight they had witnessed; and as other trees were found equally as large, they became willing witnesses, not only to the entire truthfulness of Mr. Dowd’s account, but also to the fact, that, like the confession of a certain Persian queen concerning the wisdom of Solomon, “the half had not been told.”

Mr. Lewis, one of the party above alluded to, after seeing these gigantic forest patriarchs, conceived the idea of removing the bark from one of the trees, and of taking it to the Atlantic states for exhibition, and invited Dowd to join him in the enterprise. This was declined; but, while Mr. Lewis was engaged in obtaining a suitable partner, some one from Murphy’s Camp to whom he had confided his intentions and made known his plans, took up a posse of men early the next morning to the spot described by Mr. Lewis, and, after locating a quarter section of land, immediately commenced the removal of the bark, after attempting to dissuade Lewis from the undertaking.* [* In the winter of 1854, we met Mr. Lewis in Yreka and from his own lips received this account; and we think it no more than simple justice to him here to make a record of the fact, that such an unfair and ungentlemanly violation of confidence may be both known and censured, as it well deserves to be. ] This underhanded proceeding induced Lewis to visit the large tree at Santa Cruz, discovered by Fremont, for the purpose of competing, if possible, with his quondam friend; but finding that tree, although large, only nineteen feet in diameter and 286 feet in height, while that in Calaveras county was thirty feet in diameter and 302 feet in height, he then turned his steps to some trees reported to be the greatest in magnitude in the state, growing near Trinidad. Klamath county; but the largest of these be found only to measure about twenty-four feet in diameter, and two hundred and seventy-nine feet in height; consequently, much discouraged, and after spending about five hundred dollars and several weeks’ time, he eventually abandoned his undertaking.

But a short season was allowed to elapse after the discovery of this remarkable grove, before the trumpet-tongued press proclaimed the wonder to all sections of the state, and to all parts of the world; and the lovers of the marvellous began first to doubt, then to believe, and afterward to flock from the various districts of California, that they might see, with their own eyes, the objects of which they bad heard so much.

No pilgrims to Mohamed’s tomb at Mecca, or to the reputed vestment of our Saviour at Treves, or to the Juggernaut of Hindostan, ever manifested more interest in the superstitions objects of their veneration, than the intelligent and devout worshippers of the wonderful in nature and science, of our own country, in their visit to the Mammoth-Tree Grove of Calaveras county, high up in the Sierras.

Murphy’s Camp, then known as an obscure though excellent mining district, was lifted into notoriety by its proximity to, and as the starting-point for, the Big-Tree Grove, and consequently was the centre of considerable attraction to visitors.

As very many persons will doubtless wish to visit these remarkable places, and as we cannot in this brief work describe all the various routes to these great natural marvels, from every village, town, and city in the state for they are almost as numerous and diversified as the different roads that Christians seem to take to their expected heaven, and the multitudinous creeds about the way and manner of getting there—we shall content ourselves by giving the principal ones; and, after having recited the following quaint and unanswerable argument of a celebrated divine to the querulous and uncharitably disposed members of his flock, we shall, with the reader’s kind permission, proceed on our journey.

“There was a Christian brother—a Presbyterian—who walked up to the gate of the New Jerusalem, and knocked for admittance, when ail angel who was in charge, looked down from above and inquired what he wanted. ‘To come in,’ was the answer. ‘Who and what are you?’ ‘A Presbyterian.’ ‘Sit on that seat there.’ This was on the outside of the gate; and the good man feared that he had been refused admittance. Presently arrived an Episcopalian, then a Baptist, then a Methodist, and so on, until a representative of every Christian sect had made his appearance: and were alike ordered to take a seat outside. Before they had long been there,” continued the good man, “a loud anthem broke forth, rolling and swelling upon the air, from the choir within; when those outside immediately joined in the chorus. ‘Oh!’ said the angel, as he opened wide the gate, ‘I did not know you by your names, but you leave all learned one song—come in! come in! The name you bear, or the way by which you came, is of little consequence compared with your being here at all.’ As you, my brethren,” the good man went on—“as you expect to live peaceably and lovingly together in heaven, you had better begin to practice it on earth. I have done.”

As this allegorical advice needs no words of application either to the traveller at the Christian, in the hope that the latter will take the admonition of Captain Cattle, “and make a note on’t,” and an apology to the reader for this digression, we will enter at once upon our pleasing task.

To those who reside in, or contiguous to, and wish to start from San Francisco, the most direct route to any of the mammoth-tree groves is by Stockton. That city call be reached by steamboat or stage. To take the latter, the traveller should cross the bay in the first of the Contra Costa ferry-boats for Oakland which generally leave the Vallejo street wharf, San Francisco, every morning, at eight A.M.—and thence proceed overland; if this former, he should repair to the Broadway street wharf a little before four o’clock P.M., on any day (Sundays excepted). This being the route mostly travelled, we shall confine am attention mainly to it.

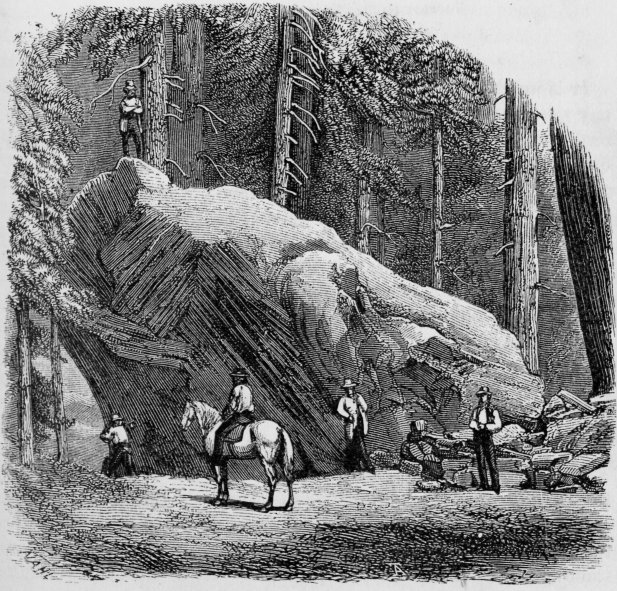

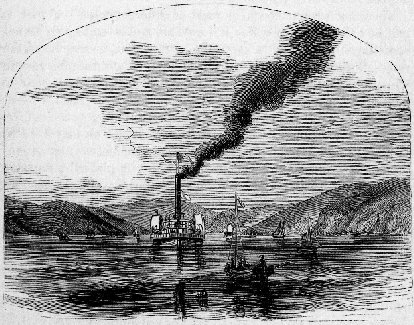

There, probably, is not a more exciting and bustling scene of

STEAMBOATS LEAVING THE WHARF—THE ANTELOPE FOR SACRAMENTO, AND THE BRAGDON FOR STOCKTON. |

On these occasions, too, there is almost sure to be one or more intentional passengers that arrive just too late to get aboard, and who, in their excitement, often throw an overcoat or valise on the boat, or overboard, but neglect to embrace the only opportune moment to get on board themselves, and we consequently left behind, as these boats are always punctual to their time of starting.

With the reader’s consent, as he may be a stranger to the various scenes of our beautiful California, we will bear him company, and explain some of the objects we may see. As it is always cool in San Francisco on a summer afternoon, we would invite him to please put on his overcoat or cloak, and let us take a cosy seat together on dock; and, while the black volumes of smoke are rolling from the tops of the funnels, and our boat is shooting past this wharf, and that vessel now lying at anchor in the bay, or, while numerous nervous people are troubled about their baggage, asking the porter all sorts of questions, let us have a quiet chat upon the sights we may witness on our trip.

The first object of interest that we find after leaving the wharves of the city behind, is

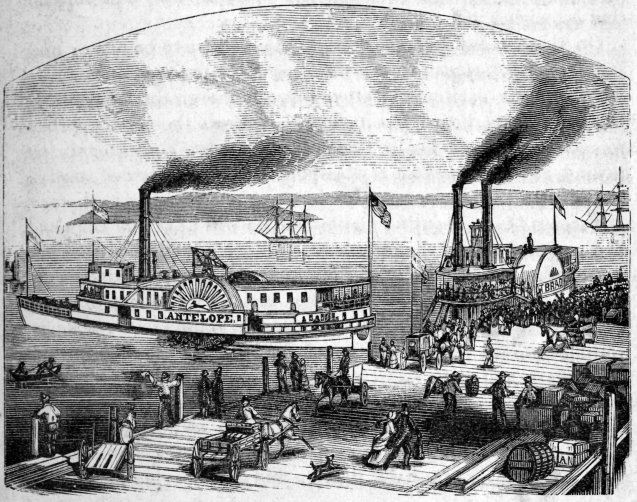

ALCATRACES ISLAND. |

This, we see, is just opposite the Golden Gate, and about half way between San Francisco and Angel Island. It commands the entrance to the great bay of San Francisco, and is but three and a half miles from Fort Point.

This island is one hundred and forty feet in height above low tide, four hundred and fifty feet in width, and sixteen hundred and fifty feet in length; somewhat irregular in shape, and fortified on all sides. The large building on its summit, about the centre or crest of the island, is a defensive barracks or citadel, three stories high, and in time of peace will accommodate about two hundred men, and, in time of war, at least three times that number. It is not only a shelter for the soldiers, and will withstand a respectable cannonade, but from its top a murderous fire could be poured upon its assailants at all parts of the island, and from whence every point of it is visible. There is a belt of fortifications encircling the island, consisting of a series of Barbette batteries, mounting, altogether, about ninety-four guns—twenty-four, forty-two, sixty-eight, and one hundred and thirty-two pounders.

The first building that you notice, after landing at the wharf, is a massive brick and stone guard-house, shot and shell proof, well protected by a heavy gate and drawbridge, and having three embrasures for twenty-four pound howitzers, that command the approach from the wharf. The top of this, like the barracks, is flat, for the use and protection of riflemen. Other guard-houses, of similar construction, are built at different points, between which there we long lines of parapets sufficiently high to preclude the possibility of an escalade; and back of which are circular platforms for mounting guns of the heaviest calibre, some of which weigh from nine to ten thousand pounds. In addition to these, there are three bomb-proof magazines, each of which will bold ten thousand pounds of powder. On the south-eastern side of the island is a large furnace for the purpose of heating cannon balls, and other similar contrivances are in course of construction.

Unfortunately, there is no natural supply of water on the island, so that all of that element which is used there is taken from Sancelito. In the basement of the barracks is a cistern, capable of holding fifty thousand gallons of water, a portion of which call be supplied from the roof of that building in the rainy season.

Appropriations have been made for the fortification of this island, to the amount of eight hundred and ninety-six thousand dollars; and about one hundred thousand dollars more will complete them. From forty to two hundred men have been employed upon these works since their commencement in 1853.

At the south-eastern end of the island is a fog-bell, of about the same weight as that at Fort Point, which is regulated to strike by machinery once in about every fifteen seconds.

The whole of the works on this island we under the skilful superintendence of Lieutenant McPherson, who very kindly explained to us the strength and purposes of the different fortifications made.

The lighthouse, at the south of the barracks, contains a Fresnel lantern of the third order, and which can be seen, on a clear night, some twelve miles outside the heads, and is of great service in suggesting the course of a vessel when entering the bay.

Yet, as we am sailing on at considerable speed across the entrance to the bay, toward Angel Island, we must not linger here, even in imagination; especially as we can now look out through the far-famed Golden Gate; the golden-hinged hope of many, who, with lingering eyes, have longed to look upon it, and to enter through its charmed portals to this land of gold. How many, too, have longed and hoped, for years, to pass it once again, on their way out to the endeared and loving hearts that wait to welcome them, at that dear spot they still call “Home!’ God bless them!

Now the vessel is in full sail, and steamships that are entering the heads, as well as those within that are tacking, now on this stretch, and now on that, to make way out against the strong north-west breeze that blows in at the Golden Gate for five-eighths of the year, we fast being lost to sight, and we am just abreast of

This island, but five miles from the city of San Francisco, was granted by Governor Alvarado to Antonio M. Asio, by order of the government of Mexico, in 1837; and by him sold to its present owners in 1853. As it contains some eight hundred some of excellent land, it is by far the largest and most valuable of any in the bay of San Francisco, and the green wild oats that grow to its very summit, in early spring, give excellent pasturage to stock of all kinds; while the natural springs, at different points, afford abundance of water at all seasons. At the present time them are about five hundred sheep roaming over its fertile hills. A large portion of the land is susceptible of cultivation, for grain and vegetables.

From the inexhaustible quarries of hard, blue, and brown sandstone that here abound, have been taken nearly all of the stone used in the foundations of the numerous buildings in San Francisco. The extensive fortifications at Alcatraces Island, Fort Point, and other places, have been faced with it; and the extensive government works at Mare Island have been principally built with stone from those quarries; yet many thousands of tons will be required from the same source, before the fortifications and other government works are completed. Clay is also found in abundance, and of an excellent quality for making bricks.

In 1856 Angel Island was surveyed by United States Engineers, for the purpose of locating sites for two twenty-four gun batteries, which are in the line of fortifications required, before our magnificent harbor may be considered as fortified. The most important of these batteries will be on the north-west point of the island, and will command Raccoon Straits; and, until this is built, our navy yard at Mare Island, and even the city of San Francisco itself, cannot be considered safe, inasmuch as, through these straits, ships of war could easily enter; if, by means of the heavy fog that so frequently hangs over the entrance to the bay, or other cause, they once passed Fort Point in safety. But here we are just opposite

This singular looking island was formerly called Treasure, or Golden Rock, in old charts, from a traditionary report being circulated

VIEW OF RED (OR TREASURE) ROCK. |

There are several strata of rock, of different colors—if rock it can be called—one of which is very fine, and resembles an article sometimes found upon a lady’s toilet-table—of course in earlier days—known as rouge-powder. Besides this there are several strata of a species of clay or colored pigment, of from four to twelve inches in thickness, and of various colors. Upon the beach numerous small red pebbles, very much resembling cornelian, are found. There can be but little wonder it should be called “Red Rock,” by plain, matter-of-fact people like ourselves. It is covered with wild oats to its summit, on which is planted a flag-staff and cannon. Some four years ago its locater and owner, Mr. Selim E. Woodworth, took about half a dozen tame rabbits over to it, from San Francisco, and now there are several hundred.

As Mr. Woodworth, before becoming a benedict, made this his place of residence, he partially graded its apparently inaccessible sides; and at different points planted several ornamental tress. A small bachelor’s cabin stands near the water’s edge, and as this affords the means of cooking fish and sundry other dishes, its owner, and a small party of friends, pay it an occasional visit for fishing and general recreation. Several sheep roam about on the island; and, as they seldom drink water, they do not feel the loss of that which nature has here failed to supply.

But on, on, we sail, and pass Maria Island and the Two Sisters.

VIEW OF THE TWO SISTERS. |

After leaving these behind, and shooting by Point San Pablo, we enter the large bay of that name; and are charmed with the fine table and grazing lands on our right, at the foot of the Contra Costa range of hills.

VIEW OF THE STRAITS OF CARQUINEZ. |

Just before entering the Straits of Carquinez, that connects the bays of San Pablo and Suisun, on our left, we obtain a glimpse of the government works at Mare Island and the town of Vallejo; but as we shall probably have something to my about these points at some future time, we will now take a look at the straits. As the stranger approaches these for the first time, he makes up his mind that the vessel on which be stands is out of her course, and is certainly running toward a bluff, and will soon be in trouble if she does not charge her course, but as he advances and the entrance to this narrow channel becomes visible, he concludes that a few moments ago be entertained a very foolish idea.

Now, however, the bell of the steamboat and a porter both announce that we are coming near Benicia, and that those who intend disembarking here, had better have their baggage and their ticket in readiness.

One would suppose as the boat nears the wharf that she is going to ran “right into it,” but soon she moves gracefully round and is made fast; but while those ashore, and those aboard, are eagerly scanning each other, to see if there is any familiar face to which to give the nod of recognition, or the cordial waving of the hand in friendly greeting, we will take our seats, and say a word or two, about this city.

Benecia was founded, in the fall of 1847, by the late Thomas O. Larkin and Roland Semple (who was also the originator and editor of the first California newspaper published at Monterey, August 15th, 1846, entitled The Californian), upon land donated them for the purpose by General M. G. Vallejo, and named in honor of the general’s estimable lady.

In 1848, a number of families took up their residence here. During the fall of that year a public school was established, which has been continued uninterruptedly to the present. In the ensuing spring a Presbyterian church was organized, and has continued under its original pastor to the present time.

The peculiarly favorable position of Benicia recommended it, at an early day, as a suitable place for the general military headquarters of the United States, upon the Pacific. Being alike convenient of access both to the sea-board and interior, and far enough from the coast to be secure against sudden assault in time of war, it was seen that no more favorable position could be selected, as adapted to all contingencies. These views met the approval of the general government; and accordingly extensive storehouses were built, military posts established, and arrangements made for erecting here the principal arsenal on the Pacific coast.

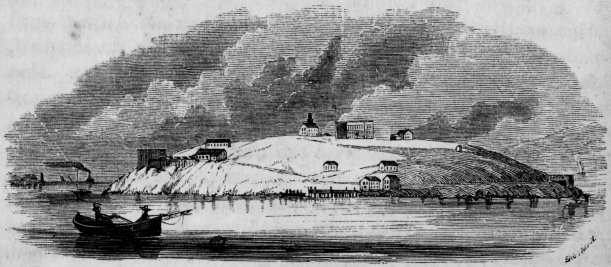

VIEW OF THE CITY OF BENICIA. |

There already are erected barracks for the soldiers, and officers’ quarters; two magazines, capable of holding from six thousand to seven thousand barrels of gunpowder of one hundred pounds each; two storehouses filled with gun-carriages, cannon, ball, and several hundred stand of small arms; besides workshops, etc.

About one hundred men are now employed, under the superintendence of Captain F. D. Calender, in the construction of an arsenal two hundred feet in length by sixty feet in width, and three stories in height, suitably provided with towers, loop-holes, windows, etc. Besides this, a large citadel is in course of erection. Two hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars have already been appropriated to them works, and they will most probably require as much more before the whole is completed.

Here, too, are ten highly and curiously ornamented bronze cannon, six eight pounders and four four-pounders, that were brought originally from old Spain, and taken at Fort Point during our war with Mexico. The following names and dates, besides coats of arms, etc., are inscribed on some of them:

“San Martin, Ano. D. 1684.”

“Poder, Ano. D. 1693.”

“San Francisco, Ano. D. 1673.”

“San Domengo, Ano. D. 1679.”

“San Pedro, Ano. D. 1628.”

As the barracks are merely a depot for the reception and transmission of troops, it is difficult to say how many soldiers are quartered here at any one time.

There are numerous other interesting places about Benicia, one of which is the extensive works of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, where all the repairs to their vessels are made, coal deposited, etc., etc.

In 1853, Benicia was chosen the capital of the state by our peripatetic legislature, and continued to hold that position for about a year, when it was taken to Sacramento, where it still (for a wonder) remains.

And, though last, by no means the least important feature of Benicia, is the widely-known and deservedly flourishing boarding, school for young ladies, the Benicia Seminary, under the charge of Miss Mary Atkins, founded in 1852, and in which several young ladies have taken graduating honors.

Next to this is the collegiate school for young gentlemen, under the superintendence of Mr. Flatt, and which was established in 1853; adjoining which is the college of Notre Dame, for the education of Catholic children. These, united to the excellent sentiments of the people, make Benicia a favorite place of residence for families.

Nearly opposite to Benicia, and distant only three miles, is the pretty agricultural village of Martinez, the county-seat of Contra Costa county. A week among the live-oaks, gardens, and farms in and around this lovely spot, will convince the most sceptical that there are few more beautiful places in any part of the state. A steam ferry-boat plies across the straits between this place and Benicia, every hour in the day. The Stockton boat always used to touch here both going and returning.

The run across the Straits of Carquinez, from Benicia to Martinez, three miles distant, takes about ten minutes. Then, after a few moments’ delay, we again dash onward—the moonlight gilding the troubled waters in the wake of our vessel, as she plows her swift way through the Bay of Suisun, and to all appearance deepens the shadows on the darker sides of Monte Diablo, by defining, with silvery clearness, the uneven ridges and summit of that solitary mountain mass.

But now we must hurry on our way, as the steamboat is by this time passing the different islands in the Bay of Suisun, named as follows: Preston Island, King’s, Simmons’, Davis’, Washington, Knox’s, Jones’, and Sherman’s Island; while on our right, boldly distinct in outline and form, stands

Almost every Californian has seen Monte Diablo. It is the great central landmark of the state. Whether we are walking in the streets of San Francisco, or sailing on any of our bays and navigable rivers, or riding on any of the roads in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys, or standing on the elevated ridges of the mining districts before us—in lonely boldness, and at almost every turn, we see Monte del Diablo. Probably from its apparent omnipresence we are indebted to its singular name, Mount of the Devil.

Viewed from the north west or south-east, it appears double, or with two elevations, the points of which are about three miles apart. The south-western peak is the most elevated, and is three thousand seven hundred and sixty feet above the sea.

For the purpose of properly surveying the state into a network of township lines, three meridians or initial points were established by the United States Survey, namely: Monte Diablo,

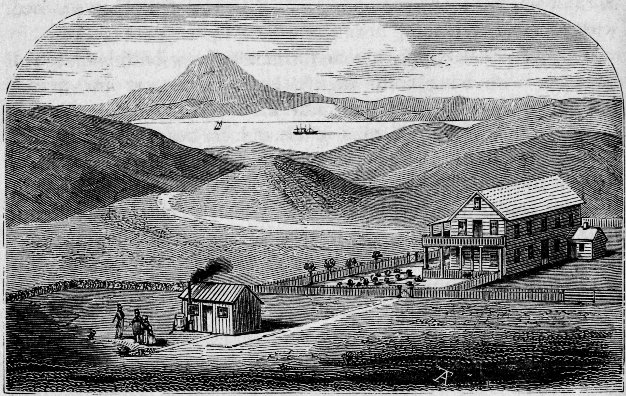

MONTE DIABLO, WITH A PORTION OF SUISUN BAY, FROM THE SULPHUR-SPRING HOUSE. |

The geological formation of this mountain is what is usually termed “primitive;” surrounded by sedimentary rocks abounding in marine shells. Near the summit there are a few quartz veins, but whether gold-bearing or not has not yet been determined. About one-third of the distance from the top on the western slope, is a “hornblende” rock of peculiar structure, and said by some to contain gold. In the numerous spurs at the base, there is an excellent and inexhaustible supply of limestone.

At the eastern foot of the mountains, about five miles from the San Joaquin River, three veins of stove coal have been discovered, and are now being worked with good prospects of remuneration, as the veins grow thicker and the quality better, as they proceed with their labors.

It is said that copper ore and cinnabar have both been found here, but with what truth we are unable to determine. Some Spaniards have reported that they know of some rich mineral there; but do not tell of what kind, and, for reasons best known to themselves, will neither communicate their secret to others nor work it themselves.

If the reader has no objection, we will climb the mountain—at least in imagination, as the captain, although an obliging man enough, will not detain the boat for us to ascend it de facto—and see what further discoveries we can make.

Provided with good horses—always make sure of the latter on any trip you may make, reader—an excellent telescope, and a liberal allowance of luncheon, let us leave the beautiful village of Martinez at seven o’clock A.M. For the first four miles, we ride over a number of pretty and gently rolling hills, at a lively gait, and arrive at the Pacheco Valley, on the edge of which stands the flourishing little village of Pacheco. We now dash access the valley at good speed for eight miles, in a south-east direction, and reach the western foot of Monte Diablo, after a good hour’s pleasant ride.

For the first mile and a half of our ascent we have a good wagon road, built in 1852, to give relay access to a quartz lead, from which considerable rack was taken in wagons to the Bay of Suisun, and, after being shipped to San Francisco, for the purpose of being tested, was found to contain gold, but not in sufficient quantities to pay for working it; for the next two miles, a good, plain trail to the main summit, passes several clear springs of cold water.

From the numerous tracks of the grizzly bears that were seen at the springs, we may naturally conclude that such animals have their sleeping apartments among the bunches of chaparal in the cañons yonder: and, if we should see the track-makers before we return, we hope our companions will keep up their courage and sufficient presence of mind to prevent themselves imitating Mr. Grizzly at the spring—at least not in the direction of the settlements—and leave us alone in our glory.

As you will perceive, the summit of the mountain is reached without the necessity of dismounting; and as there are wild oats all around, and the stores of sundries provided have not been lost or left behind, suppose we rest and refresh ourselves, and allow our animals to do the same.

The sight of the glorious panorama unrolled at our feet, we need not tell you, amply repays us for our early ride. As we look around us, we may easily imagine that perhaps the priests who named this mountain may have climbed it, and as they saw the wonders spread out before them, recalled to memory the following passage of holy writ: “The devil taketh him [Jesus] up into an exceeding high mountain, and sheweth him all the kingdoms of the world, and the glory of them; and saith unto him, All these things will I give thee, if then wilt fall down and worship me” (Matthew 4th, verses 8 and 9); and from this time called it Monte del Diablo. Of course, this is mere supposition, and is as likely to be wrong as it is to be right.

The Pacific Ocean; the city, and part of the bay of San Francisco; Fort Point; the Golden Gate; San Pablo and Suisun Bays; the government works at Marc Island; Vallejo; Benicia; the valleys of Santa Clara, Petaluma, Sonoma, Napa, Sacramento, and San Joaquin, with their rivers, creeks, and sloughs, in all their tortuous windings; the cities of Stockton and Sacramento; and the great line of the snow-covered Sierras; with numerous villages dotting the pine forests on the lower mountain range—are all spread out before you. In short, there is nothing to obstruct the sight in any direction; and, with a good glass, the steamers and vessels at anchor in the bay, and made fast at the wharves of San Francisco, are distinctly visible.

Stock may be seen grazing, in all directions, on the mountains. To the very summit, wild oats and chaparal alternately grow. In the cañons are oak and pine trees from fifty to one hundred feet in height; and, on the more exposed portions, there are low trees from twenty to thirty feet in height.

In the fall season, when the wild oats and dead bushes are perfectly dry, the Indians sometimes set large portions of the surface of the mountains on fire; and, when the breeze is fresh, and the night is dark, and the lurid flames leap, and curl, and sway, now to this side and now to that, the spectacle presented is magnificent beyond the power of language to express.

The Sacramento about, we see, is going straight forward, and will soon enter the Sacramento River, up which her course lies; while ours is to the right—past “New York of the Pacific,” a place now containing only two or three small dilapidated houses, but which was once intended by speculators to be the great commercial emporium of this coast—up the San Joaquin.

The evening being calm and sultry, it soon becomes evident that, if it is not the height of the musquito season, a very numerous band are out on a freebooting excursion; and, although their harvest-home song of blood is doubtless very musical, it is matter of regret with us to confess that, in our opinion, bill few persons on board appear to have any ear for it. In order, however, that their musical efforts may not be entirely lost sight of, they— the musquitos—take pleasure in writing and impressing their low refrain, in red and embossed notes, upon the foreheads of the passengers, so that he who looks may read, “Musquitos!” when, alas! such is the ingratitude felt for favors so voluntarily performed, that flat-handed blows are dealt out to them in impetuous haste; and blood, blood, blood, and flattened musquitos, are written, in red and dark brown spots, upon the smiter; and the notes of those singers are heard no more!

While the unequal warfare is going on, and one carcass of the slain induces at least a dozen of the living to come to his funeral and avenge his death, we are sailing on, on, up one of the most crooked and monotonous navigable rivers out of doors; and, as we may as well do something more than fight the little, bill-presenting, and tax-collecting musquitos, if only for variety, we will relate to the reader bow, in the early spring of 1849, just before leaving our southern home on the banks of “The Father of Waters,” the old Mississippi, a gentleman arrived from northern Europe, and was at once introduced. a member of our little family circle. Now, however strange it may appear, our new friend had never in his life looked upon a live musquito, or a musquito-bar, and, consequently, knew nothing about the arrangements of a good femme de charge for passing a comfortable night, where such insects were even more numerous than oranges. In the morning he seated himself at the breakfast-table, his face newly covered with wounds received from the enemy’s proboscis, when an inquiry was made by the lady of the house if he had passed the night pleasantly. “Yes-yes,” be replied with some hesitation “yes—toler-a-bly pleasant; although—a—small—fly—annoyed me—somewhat!” At this confession we could restrain ourselves no longer, but broke out into a hearty laugh, led by our good-natured hostess, who then exclaimed: “Musquitos! why, I never dreamed that the marks on your face were musquito bites. I thought they might be from a rash, or something of that kind. Why, didn’t you lower down your musquito-bars?” But, as this latter appendage to a bed, on the low, alluvial lands of a southern river, was a greater stranger to him than any dead language known, the “small fly” problem had to be satisfactorily solved, and his sleep made sweet.

Perhaps it may be well here to remark, that the San Joaquin River is divided into three branches, known, respectively, as the west, middle, and east channels—the latter named being not only the main stream, but the one used by the steamboats and sailing-vessels bound to and from Stockton—or, at least, to within four miles of that city, from which point the Stockton slough is used. The east, or main channel, is navigable for small, stern-wheel steamboats as high as Frezno City. Besides the three main channels of the San Joaquin, before mentioned, there are numerous tributaries, the principal of which are the Moquelumne, Calaveras, Stanislaus, Tuolumne, and Merced Rivers.

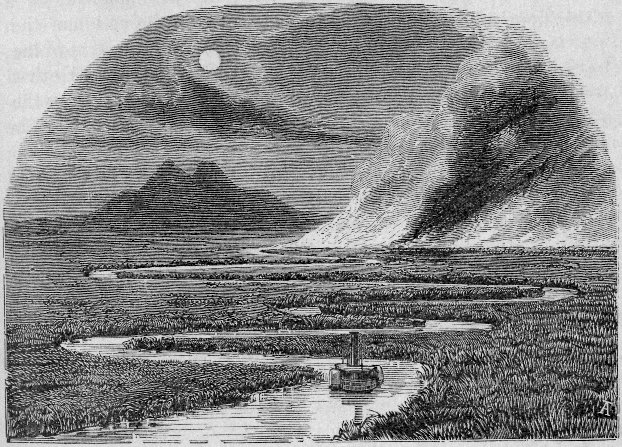

An apparently interminable sea of tules extends nearly one hundred and fifty miles, south, up the valley of the San Joaquin; and when these we on fire, as they not unfrequently are, during the fall and early winter months, the broad sheet of licking and leaping flame, and the vast volumes of smoke that rise, and eddy, and surge, hither and thither, present a scene of fearful grandeur at night, that is suggestive of some earthly pandemonium.

NIGHT SCENE ON THE SAN JOAQUIN RIVER—MONTE DIABLO IN THE DISTANCE. |

The lumbering sound of the boat’s machinery has suddenly ceased, and our high-pressure motive power, descended from a regular to an occasional snorting, gives its a reminder that we have reached Stockton. Time, half-past two o’clock A.M.

At day-break we us again disturbed in our fitful slumbers, by the rumbling of wagons and hurrying bustle of laborers discharging cargo; and before we have scarcely turned over for another uncertain nap, the stentorian lungs of some employee of the stage companies announce, that “stages for Sonora, Columbia, Moquelumne Hill, Sacramento, Mariposa, Coulterville, and Murphy’s, are just about starting.”

The reader knows as well as we do, that it is of no use, whatever, to be in too great a hurry when we are sight-seeing; consequently, with his permission, we will allow the stages to depart without us this morning, and take a quiet walk about the city.

This flourishing commercial city is situated in the valley of the San Joaquin, at the head of a deep navigable slough or arm of the San Joaquin River, about three miles from its junction with that stream. The luxuriant foliage of the trees and shrubs impress the stranger with the great fertility of the soil; and the unusually large number of windmills with the manner of irrigation. So marked a feature as the latter has secured to this locality the cognomen of “the City of Windmills.”

The land upon which the city stands is part of a grant made by Governor Micheltorena, to Captain C. M. Weber and Mr. Gulnac, in 1844, who most probably were the first white settlers in the valley of the San Joaquin; although some Canadian Frenchmen, in the employ of the Hudson Bay Company, spent several hunting seasons here, commencing as early as 1834.

In 1813, an exploring expedition, under Lieutenant Gabriel Morago, visited this valley, and gave it its present name—the former one being “Valle de los Tulares,” or Valley of Rushes. At that time, it was occupied by a large and formidable tribe of Indians, called the Yachicumnes, who, in after times, were for the most part captured and sent to the Missions Dolores and San Jose, or decimated by the small-pox, and now are nearly extinct. Under the maddening influence of their losses by death from that fatal disease, they rose upon the whites, burned their buildings and killed their stock, and forced them to take shelter at the Missions.

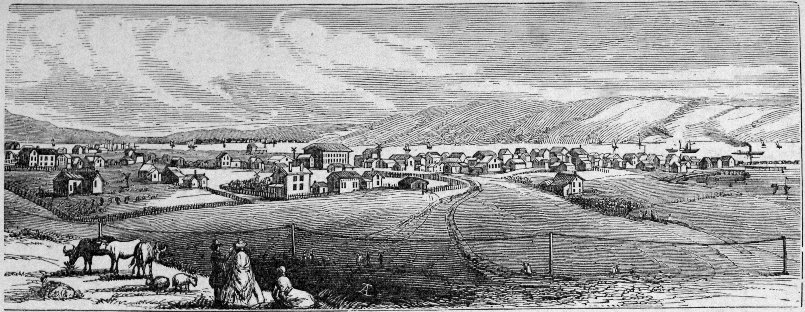

In 1846, Mr. Weber, reinforced by a number of emigrants, renewed his efforts to form a settlement; but the war breaking out, compelled him to seek refuge in the larger settlements, until the Bear flag was hoisted, when Captain Weber, from his knowledge of the country, and the devotedness of those who had placed

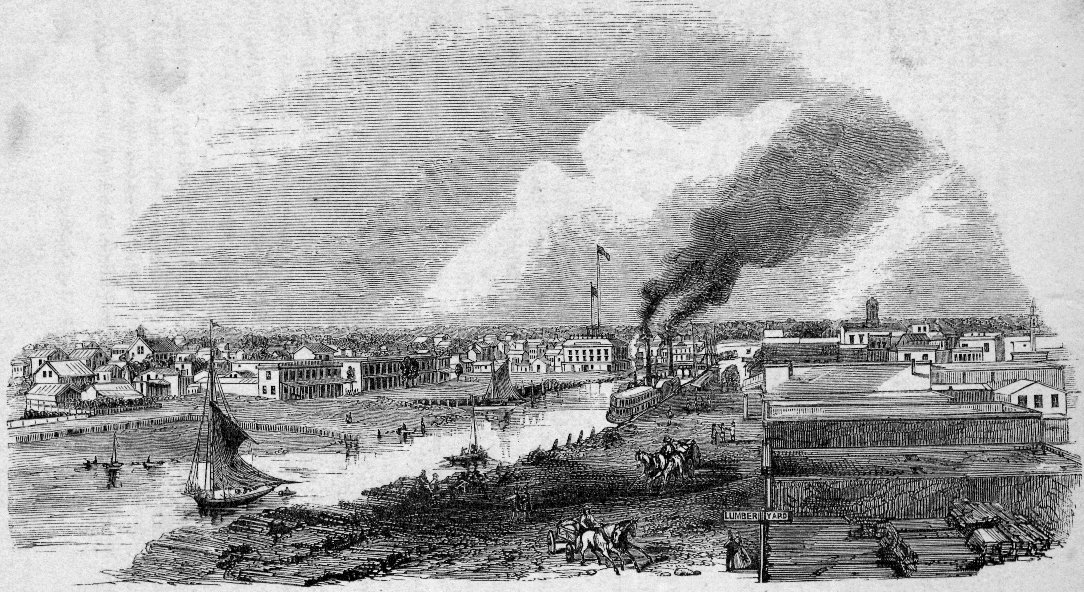

VIEW OF THE CITY OF STOCKTON. |

When the war was concluded, in 1848, another and successful attempt was made to establish a prosperous settlement here, but upon the discovery of gold it was again nearly deserted.

Several cargoes of goods having arrived from San Francisco, for land transportation to the southern mines, were suggestive of the importance of this spot for the foundation of a city, when cloth tents and houses sprung up as if by magic. On the 23d of December, 1849, a fire broke out for the first time, and the “linen city,” as it was then called, was swept away, causing a loss of about two hundred thousand dollars. Almost before the ruins had ceased smouldering, a newer and cleaner “linen city,” with a few wooden buildings, was erected in its place. In the following spring, a large proportion of the cloth houses gave place to wooden structures; and, being now in steam communication with San Francisco, the new city began to grow substantially in importance.

On the 30th of March, 1850, the first weekly Stockton newspaper was published by Radcliffe and White, conducted by Mr. John White.

On the same day, the first theatrical performance was given, in the Assembly Room of the Stockton House, by Messrs. Bingham and Fury.

On the 13th of May following, the first election was held—the population then numbering about two thousand four hundred.

June 26th, a fire department wag organized, and J. E. Nuttman elected chief engineer.

On the 25th of the following month an order was received from the County Court, incorporating the city of Stockton, and authorizing the election of officers. On the 1st of August, 1850, an election for municipal officers was held, when seven hundred votes were polled, with the following result:—Mayor, Samuel Purdy; Recorder, C, M. Teak; City Attorney, Henry A. Crabb; Treasurer, George D. Brush; Assessor, C. Edmondson; Marshal, T. S. Lubbock.

On the 6th of May, 1851, a fire broke out that nearly destroyed

“THE PRAIRIE SCHOONER.” |

In 1852, steps were taken to build a City Hall; and about the same time, the south wing of what is now the State Asylum for the Insane was erected as a General Hospital; but which was abolished in 1853, and the Insane Asylum formed into a distinct institution by an act of the Legislature. In 1854 , the central building was added, and in 1855, the kitchen, bakery, dining-rooms, and bath-rooms were also added.

On the 1st of February, 1856, another fire destroyed property to the amount of about sixty thousand dollars; and on the 30th of July following, by the same cause, about forty thousand dollars’ worth of property was swept away.

Of churches, there is all Episcopal, Presbyterian, Methodist Episcopal, Catholic, Methodist Episcopal South, First and Second Baptist, Jewish Synagogue, German Methodist, and African Methodist.

There are two daily newspapers published here, the San Joaquin Republican, Conley and Patrick, proprietors; and the Stockton Daily Argus, published by William Biven. Each of these issue a weekly edition.

Of public schools there are four—two grammar and two primary—in which there are about two hundred scholars in daily attendance, and four teachers, one to each school. There are also four private seminaries,— Dr. Collins’, Dr. Hunt’s, Miss Bond’s, and Mrs. Gates’.

Stockton can boast of having the deepest artesian well in the state, which is one thousand and two feet in depth, and which throws out two hundred and fifty gallons of water per minute, fifteen thousand per hour, and three hundred and sixty thousand gallons every twenty-four hours, to the height of eleven feet above the plain, and nine feet above the city grade. In sinking this well, ninety-six different strata of loam, clay, mica, green sandstone, pebbles, etc., were passed through. Three hundred and forty feet from the surface, a redwood stump was found, imbedded in sand, from whence a stream of water issued to the top. The temperature of the water is 77° Fahrenheit—the atmosphere being only 60°. The cost of this well was ten thousand dollars.

One of the principal features connected with the commerce of this city, is the number of large freight wagons, laden for the mines; these have, not inappropriately, been denominated “prairie schooners,” and “steamboats of the plains.” One team, belonging to Mr. Warren, has taken one hundred thousand pounds to Mariposa in four trips, thus averaging twenty-five thousand per trip. Another team, belonging to Mr. Huffman, hauled thirty-two thousand from Staple’s Ranche to Stockton. Twenty-nine thousand six hundred and eighty pounds of freight, in addition to seven hundred pounds of feed, were hauled to Jenny Lind—a mining town on the Moquelumne Hill road, twenty-seven miles from Stockton—by twelve mules. The cost of these wagons is from nine hundred to eleven hundred and fifty dollars. In length, they we generally from twenty to twenty-three feet on the top, and from eighteen to nineteen feet on the bottom. Mules cost upon the average three hundred and fifty dollars each; and some very large ones sell as high as one thousand four hundred dollars the span. One man drives and tends as many as fourteen animals, guiding and driving with a single line. These towns have nearly superseded the use of pack trains, inasmuch as formerly the number of animals in the packing trade exceeded one thousand five hundred, and now it is only about one hundred and sixty. It would be a source of considerable amusement to our eastern friends, could they see how easily these large mules are managed. They are drilled as soldiers, and are almost as tractable. When a teamster cracks his whip, it words like the sharp quick report of a revolver, and nearly as loud.

Several stages leave Stockton daily at six o’clock A. M., as follows: For Sacramento City, fare five dollars; San Francisco, fare five dollars; Sonora, Columbia, and Murphy’s Camp, fare eight dollars. On alternate days at the same hour for Mariposa, fare ten dollars—this journey is accomplished in two days; Coulterville—changing stages at the Mound Springs, through in one day—fare, seven dollars and four dollars, making eleven dollars; Moquelumne River road, fare from one dollar to five dollars. It perhaps ought to be here remarked, that coach fares generally differ, according to the number and force of “opposition” lines, so that the above must be understood as about the regular charges.

“All aboard for Murphy’s!” cries the coachman; “All set!” shouts somebody in answer; when, “crack goes the whip, and away go we.”

There is a feeling of jovial, good-humored pleasureableness that steals insensibly over the secluded residents of cities when all the cares of a daily routine of duties we left behind and the novelty of fresh scenes forms new sources of enjoyment. Especially is it so when seated comfortably in an easy old stage, with the prospect before us of witnessing one of the most wonderful sights to be found in any far-off country, either of the old or new world. Besides, in addition to our being in the reputed position of a Frenchman with his dinner, who is said to enjoy it three times—first, by anticipation; second, in participation; and third, upon retrospection; we have new views perpetually breaking open our admiring sight.

As soon as we have passed over the best gravelled streets of any town or city in the state, without exception, we thread our way past the beautiful suburban residences of the city of Stockton, and emerge from the shadows of the giant oaks that stand on either side the road. The deliciously cool breath of early morning, laden as it is in spring and early summer, with the fragrance of myriads of flowers and scented shrubs, we inhale with an acme of enjoyment that contrasts inexpressibly with the almost stifling and unsavory warmth of a liliputian state-room on board a high-pressure steamboat.

The bracing air will soon restore the loss of appetite resulting from, and almost consequent upon, the excitement created by the novel circumstances and prospects attending us, so that when we arrive at the first public-house for a change of horses, and breakfast is announced, it is not by any means an unwelcome sound. The inner man being allowed about fifteen minutes to receive satisfaction, and a fresh relay of horses provided, we are soon upon our way again. At the “twenty-seven mile house,” we again “change” horses. By this time the day and the travellers all become warm together; and as the cooling land-breeze dies out, the dust begins to poor in by every chink and aperture, so that the luxurious enjoyments of the early morning depart in the same way that lawyers are said to get to heaven—by degrees.

At “Double Springs” we are informed that dinner is upon the table, and at the low charge of one dollar per head, the hungry may effectually lose their appetites and their tempers. A few miles beyond this there are signs of mining activity apparent, and we soon pass through the prosperous town of San Andreas. Here an excellent weekly paper is published, entitled, The San Andreas Independent. Those who have never before looked upon the modus operandi of mining, would doubtless like to linger among the long-toms and sluices, the tunnels, and shafts, and see for themselves how and where the precious metal is obtained; but we must not linger to explain, as this department would occupy too much time and space fully to describe it.

Leaving San Andreas, we pass through the mining towns of Angel’s Camp, Vallecito (here we saw a lump of pure gold, shaped like a large potato, which weighed twenty-six pounds two ounces), Douglas Flat, and arrive at Murphy’s Camp about dark. Being well tired, we give cordial welcome to the many comforts of Sperry’s Hotel, and arrange for an early start for the Mammoth-Tree Grove in the morning.

Leaving the mining town of Murphy’s Camp behind, we cross the “Flat,” and—about half a mile from town—proceed, upon a good carriage road, up a narrow cañon, now upon this side of the stream, and now on that, as the hills proved favorable, or otherwise, for the construction of the road. If our visit is supposed to be in spring or early summer, every mountain side, even to the tops of the ridges, is covered with flowers and flowering-shrubs of great variety and beauty; while, on either hand, groves of oaks and pines stand as shade-giving guardians of personal comfort to the dust-covered traveller on a sunny day.

As we continue our ascent for a few miles, the road becomes more undulating and gradual, and lying, for the most part, on the top, or gently sloping sides, of a dividing ridge; often through dense forests of tall, magnificent pines, that are from one hundred and seventy to two hundred and twenty feet in height, slender, and straight as an arrow. We measured one, that had fallen, that was twenty inches in diameter at the base, and fourteen and a half inches in diameter at the distance of one hundred and twenty-five feet from the base. The ridges being nearly clear of an undergrowth of shrubbery, and the trucks of the trees, for fifty feet upward, or more, entirely clear of branches, the eye of the traveller can wander, delightedly, for a long distance, among the captivating scenes of the forest.

At different distances upon the route, the canal of the Union Water Company winds its sinuous way on the top or around the sides of the ridge; or its sparkling contents rush impetuously down the water-furrowed centre of a ravine. Here and there an aqueduct, or cabin, or saw-mill, gives variety to an ever-changing landscape.

When within about four and a half miles of the Mammoth-Tree Grove, the surrounding mountain peaks and ridges us boldly visible. Looking south-east, the uncovered head of Bald Mountain silently announces its solitude and distinctiveness; west, the “Coast Mountain range” forms a continuous girdle to the horizon, extending to the north and south, where the snowy tops of the Sierras form a magnificent back-ground to the glorious picture.

While we have been thus riding and admiring, and talking and wondering, and musing concerning the beautiful scenes we have witnessed, the deepening shadows of the densely-timbered forest we are entering, by the awe they inspire—at first gently and imperceptibly, then rapidly and almost to be felt—prepare our minds to appreciate the imposing grandeur of the objects we we about to see, just as

“Coming events cast their shadows before.”

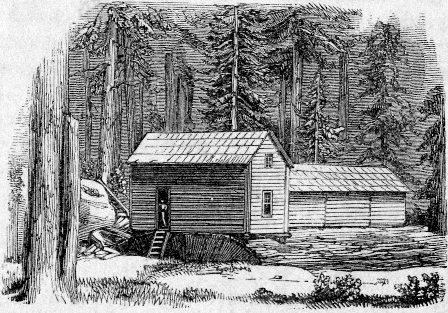

The gracefully-curling smoke from the chimneys of the Big-Tree Cottage, that is now visible; the inviting refreshment of the inner man; the luxurious feeling arising from bathing the hands and temples in cold, clear water—especially after a ride or walk— are alike disregarded. One thought, one feeling, one emotion— that of vastness, sublimity, profoundness, pervaders the whole soul; for there

*Extract from Mrs. Conner’s forthcoming play of “The Three Brothers; or, the Mammoth Grove of Calaveras: a Legend of California.”

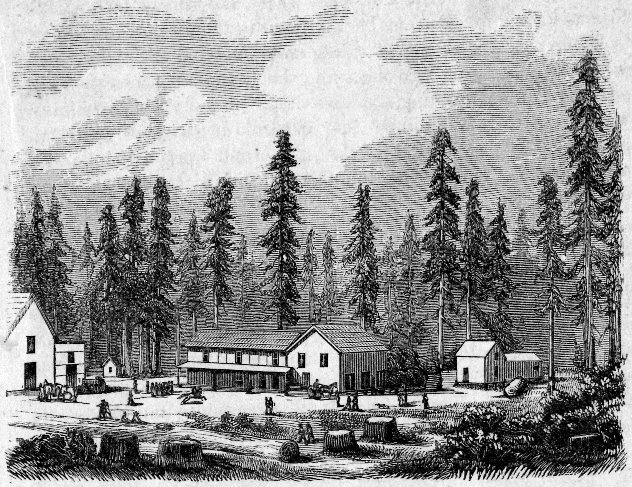

VIEW OF “THE BIG TREE COTTAGE” HOTEL. |

Before wandering further amid the wild secluded depths of this forest, it will be well that the horse and his rider should partake of some good and substantial repast, such as he will here find provided, inasmuch as it is not always wisest, or best, to explore the wonderful, or look upon the beautiful, with an empty stomach, especially after a bracing and appetitive ride of fifteen miles. While thus engaged, let us explain some matters that we have reserved for this occasion.

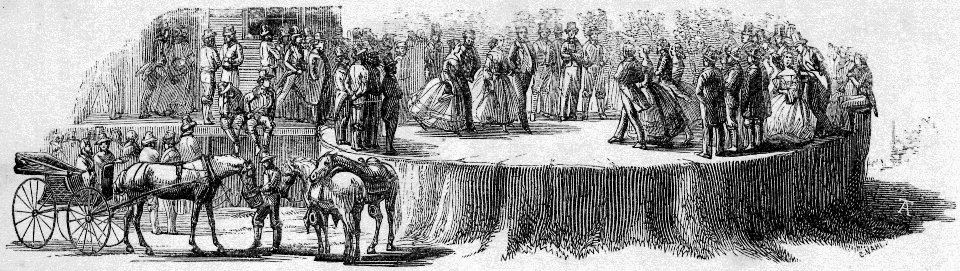

A COTILLION PARTY OF THIRTY-TWO PERSONS DANCING ON THE STUMP OF THE MAMMOTH TREE. |

The Mammoth-Tree Grove, then, is situated in a gently sloping, and, as you leave seen, heavily-timbered valley, on the divide or ridge between the San Antonio branch of the Calaveras River and the north fork of the Stanislaus River; in lat. 38° north, long. 120° 10' west; at an elevation of 2,300 feet above Murphy’s Camp, and 4,370 feet above the level of the sea; at a distance of nicety-seven miles from Sacramento City and eighty-seven from Stockton.

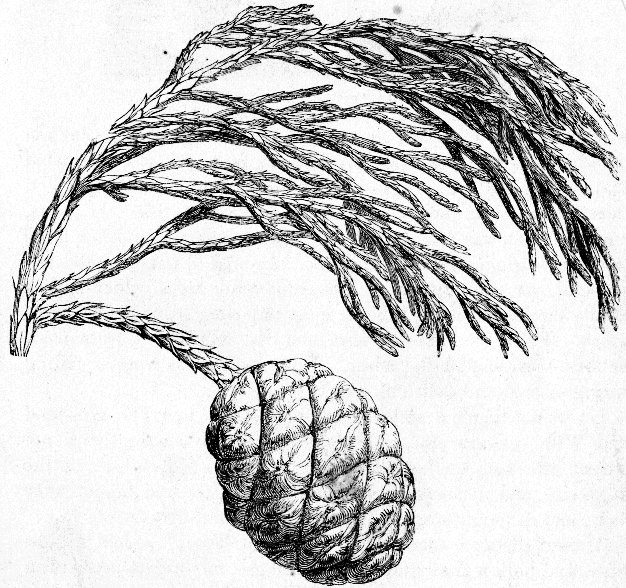

When specimens of this tree, with its cones and foliage, were sent to England for examination, Professor Lindley, an eminent English botanist, considered it as forming a new genus, and accordingly named it (doubtless with the best intentions, but still unfairly) “Wellingtonia gigantea;” but through the examinations of Mr. Lobb, a gentleman of rare botanical attainments, who has spent several years in California, devoting himself to this interesting, and, to him, favorite branch of study, it is decided to belong to the Taxodium family, and must be referred to the old genus Sequoia sempervirens; and consequently, as it is not allow genus, and as it has been properly examined and classified, it is now known, only, among scientific men, as the Sequoia gigantea (sempervirens) and not “Wellingtonia,” or, as some good and laudably patriotic souls would have it, to prevent the English from stealing American thunder, “Washingtonia gigantea.”

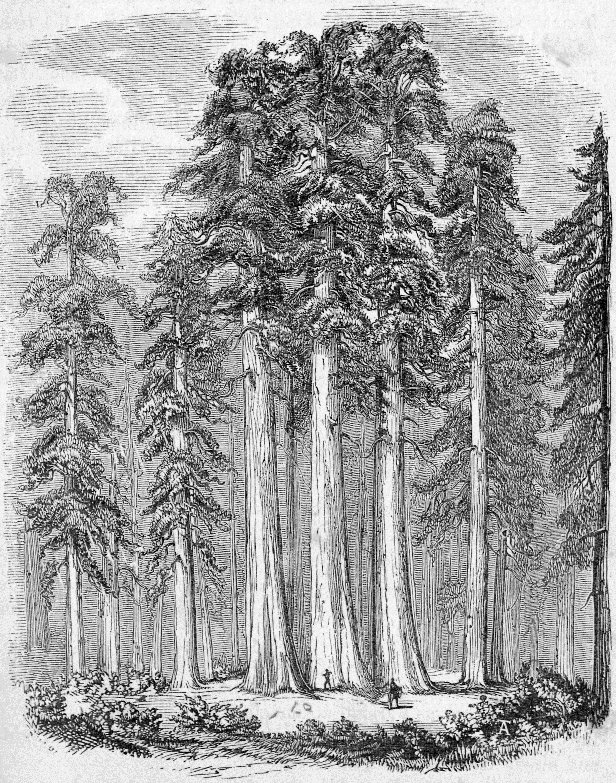

Within an area of fifty acres, there are one hundred and three trees of a goodly size, twenty of which exceed twenty-five feet in diameter at the base, and, consequently, are about seventy-five feet in circumference!

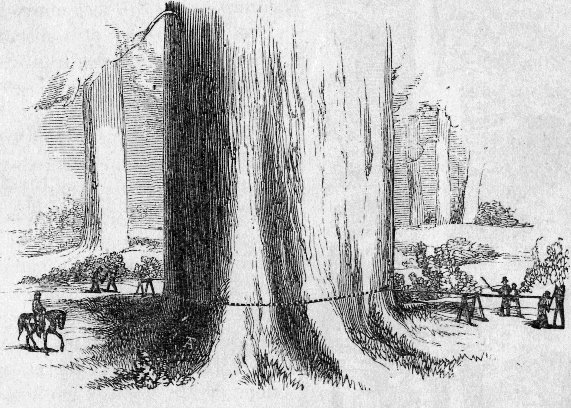

WORKMEN ENGAGED IN FELLING THE MAMMOTH TREE. |

But—the repast over—let us first walk upon the “Big-Tree Stump” adjoining the cottage. You see it is perfectly smooth, sound, and level. Upon this stump, however incredible it may seem, on the 4th of July, thirty-two persons were engaged in dancing four sets of cotillions at one time, without suffering any inconvenience whatever; and besides these, there were musicians and lookers-on. Across the solid wood of this stump, five and a half feet from the ground (now the bark is removed, which was from fifteen to eighteen inches in thickness), measures twenty-five feet, and with the bark, twenty-eight fact. Think for a moment; the snoop of a tree exceeding nine yards in diameter; and sound to the very centre.

This tree employed five men for twenty-two days in felling it— not by chopping it down, but by boring it off with pump augers. After the stem was fairly severed from the stump, the uprightness of the tree, and breadth of its base, sustained it in its position. To accomplish the feat of throwing it over, about two and a half days of the twenty two were spent in inserting wedges, and driving them in with the butts of trees, until, at last, the noble monarch of the forest was forced to tremble, and then to fall, after braving “the battle and the breeze” of nearly three thousand winters. In our estimation, it was a sacrilegious act; although it is possible, that the exhibition of the bark, among the unbelievers of the eastern part of our continent, and of Europe, may have convinced all the “Thomases” living, that we have great facts in California, that must be believed, sooner or later. This is the only palliating consideration with us for this act of desecration.

VIEW OF DOUBLE BOWLING-ALLEY ON TRUNK OF BIG TREE. |

This noble tree was three hundred and two feet in height, and ninety-six feet in circumference at the ground. Upon the upper part of the prostate trunk is constructed a long double bowling-alley, where the athletic sport of playing bowls may afford a pastime and change to the visitor.

Now let us walk, among the giant shadows of the forest, to another of these wonders—the largest tree now standing; which, from its immense size, two breast-like protuberances on one side, and the number of small trees of the same class adjacent, has been named “The Mother of the Forest.” In the summer of 1854, the bark was stripped from this tree by Mr. George Gale, for purposes of exhibition in the East, to the height of one hundred and sixteen feet; and it now measures in circumference, without the bark, at the base, eighty-four feet; twenty feet, from base, sixty-nine feet; seventy feet from base, forty-three feet six inches; one hundred and sixteen feet from base, and up to the bark, thirty-nine feet six inches. The full circumference at base, including bark, was ninety feet. Its height is three hundred and twenty-one feet. The average thickness of bark was eleven inches, although in places it was about two feet. This tree is estimated to contain five hundred and thirty-seven thousand feet of sound inch lumber. To the the first branch it is one hundred and thirty-seven feet. The small black marks upon the tree indicate points where two and a half inch auger holes were bored, into which rounds were inserted, by which to ascend and descend, while removing the bark. At different distances upward, especially at the top, numerous dates, and names of visitors, have been cut. It is contemplated to construct a circular stairway around this tree. When the bark was being removed, a young man fell from the scaffolding—or, rather, out of a descending noose, at a distance of seventy-nine feet from the ground, and escaped with a broken limb. We were within a few yards of him when he fell, and were agreeably surprised to discover that he had not broken his neck.

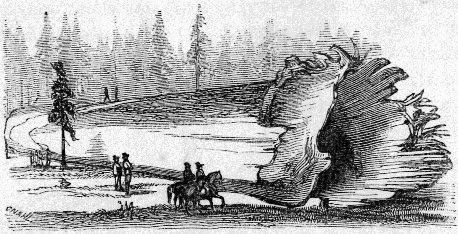

A short distance from the above lies the prostrate and majestic body of the “Father of the Forest,” the largest tree of the entire group, half-buried in the soil. This tree measures in circumference, at the roots, one hundred and ten feet. It is two hundred feet to the first branch; the whole of which is hollow, and through

VIEW OF THE “FATHER OF THE FOREST.” |

Let us not linger here too long, but pass on to “The Husband and Wife”—a graceful pair of trees that are leaning, with apparent affection, against each other. Both of these are of the same size, and measure in circumference, at the base, about sixty feet; and in height are about two hundred and fifty-two feet.

A short distance further is “The Burnt Tree;” which is prostrate, and hollow from numerous burnings—in which a person can ride on horseback for sixty feet. The estimated height of this tree, when standing, was three hundred and thirty feet, and its circumference ninety-seven feet. It now measures across the roots thirty-nine feet six inches.

“Hercules,” another of these giants, is ninety-five feet in circumference, and three hundred and twenty feet high. On the trunk of this tree is cut the name of “G. M. Wooster, June, 1850;” so that it is possible this person may some day claim precedence to Mr. Dowd, in this great discovery.* [* Since writing the above, we have made the acquaintance of Mr. Wooster who disclaims all title to the discovery, although of the same party; and gives it to W. Whitehead, Esq., who, while tying his shoe, looked casually around him, and saw the trees, June, 1850. ] At all events, it was through the latter that the world became acquainted with the grove. There are many other trees of this group that claim a passing notice; but, inasmuch as they very much resemble each other, we shall only mention them briefly.

THE CONE, AND FOLIAGE OF THE MAMMOTH TREES—FULL SIZE. |

The “Hermit,” a lonely old fellow, is 318 feet in height, and 60 in circumference; exceedingly straight and well formed.

The “Old Maid”—a sleeping, broken-topped, and forlorn-looking spinster of the big-tree family—is two hundred and sixty-one feet in height, and fifty-nine feet in circumference.

As a fit companion to the above, though at a respectful distance from it, stands; the dejected-looking “Old Bachelor.” This tree, as lonely and as solitary as the former, is one of the roughest, bark-rent specimens of the big trees to be found. In size it rather has the advantage of the “Old Maid,” being about two hundred and ninety-eight feet in height, and sixty feet in circumference.

Near to the “Old Bachelor” is the “Pioneer’s Cabin,” the top of which is broken off about one hundred and fifty feet from the ground. This tree measures thirty-three feet in diameter; but, as it is hollow, and uneven in its circumference, its average size will not be quite equal to that.

The “Siamese Twins,” as their name indicates, with one large stem at the ground, form a double tree about forty-one feet upward. These are each three hundred feet in height.

Near to them stands the, “Guardian,” a fine-looking old tree, three hundred and twenty feet in height, by eighty-one feet in circumference.

The “Mother and Son” form mother beautiful sight, as side by side they stand. The former is three hundred and fifteen feet in height, and the latter three hundred and two feet. Unitedly, their circumference is ninety-three feet.

The “Horseback Ride” is an old, broken, and long prostrate truck, one hundred and fifty feet in length, hollow from one end to the other, and in which, to the distance of seventy-two feet, a person can ride on horseback. At the narrowest place inside, this tree is twelve feet high.

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin” is another fanciful name, given to a tree that is hollow, and in which twenty-five persons can be seated comfortably (not, as a friend at our elbow suggests, in each other’s laps, perhaps!) This tree is three hundred and five feet in height, and ninety-one feet in circumference.

The “Pride of the Forest” is one of the most beautiful trees of this wonderful grove. It is well-shaped, straight, and sound; and, although not quite as large as some of the others, it is, nevertheless, a noble-looking member of the grove, two hundred and seventy-five feet in height, and sixty feet in circumference.

THE “THREE GRACES.” |

The “Beauty of the Forest” is similar in shape to the above, and measures three hundred and seven feet in height and sixty-five feet in circumference.

The “Two Guardsmen” stand by the roadside, at the entrance of the “clearing,” and near the cottage. They seem to be the sentinels of the valley. In height, these are three hundred feet; and in circumference, one is sixty-five feet, and the other sixty-nine feet.

Next—though last in being mentioned, not least in gracefulness and beauty—stand the “Three Sisters”—by some called the “Three Graces”—one of the most beautiful groups (if not the most beautiful) of the whole grove. Together, at their base, they measure in circumference ninety-two feet; and in height they are nearly equal, and each measures nearly two hundred and ninety-five feet.

Many of the largest of these trees have been deformed and otherwise injured, by the numerous and large fires that have swept with desolating fury over this forest, at different periods. But a small portion of decayed timber, of the Taxodium genus, can be seen. Like other varieties of the same species, it is less subject to decay, even when fallen and dead, than other woods.

Respecting the age of this grove, there has been but one opinion among the best informed botanists, which is this—that each concentric circle is the growth of one year; and as nearly three thousand concentric circles can be counted in the stump of the fallen tree, it is correct to conclude that these trees are nearly three thousand years old. “This,” says the Gardener’s Calendar, “may very well be true, if it does not grow above two inches in diameter in twenty years, which we believe to be the fact.”

Could those magnificent and venerable forest giants of Calaveras county be gifted with a descriptive historical tongue, how their recital would startle us, as they told of the many wonderful changes that have taken place in California within the last three thousand years!

Next: Calaveras Caves • Contents • Previous: Illustrations

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/scenes_of_wonder_and_curiosity/calaveras_big_trees.html