| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Indians > History >

| Cover illustration: Ta-bu-ce [Editor’s note: Maggie Howard—dea.], for many years a familiar figure in Yosemite, shortly before her death in 1947 at a probable age of more than 90 years. This and other illustrations in this booklet are by Ralph Anderson, unless otherwise credited. |

By Elizabeth H. Godfrey

[Editor’s note: the first printing of this book has the following foreword, which was omitted in a latter printing.—dea.]

After looking over the Indian exhibit in the museum many park visitors desire a publication on the history, habits, and livlihood of the original inhabitans of this area. With a hope of supplying such a requirement at a minimum cost, this special issue of Yosemite Nature Notes has been prepared. It is in part a compilation of historical information obtained from various articles that have appeared from time to time in Yosemite Nature Notes and other publications. Due credit must also be given James E. Cole, former Junior Park Naturalist, whose exhaustive notes on this subject were of considerable value. The help of M. E. Beatty, former Associate Park Naturalist, under whose supervision the original edition of this booklet was prepared should also be noted. The publication of this second edition was made possible through the assistance of former Park Naturalist C. Frank Brockman.

Centuries before the advent of the white man, Yosemite Valley is believed to have been inhabited by Indians. With the ravages of wars and black sickness the Ahwahneeches, a powerful tribe—and one of the last to occupy the “deep, grassy valley” —became practically annihilated The few disheartened survivors left to affiliate with other neighboring tribes.

[Editor’s note: the correct meaning of Ahwahnee is “(gaping) mouth,” not “deep, grassy valley.” See “Origin of the Place Name Yosemite”—dea.]

After many years of abandonment, a young and adventurous Indian by the name of Tenaya, who claimed to be a direct descendant of the Chief of the Ahwahneeches, and who had been born and raised among the Monos, decided to return to what he considered his homeland. From the Monos, Piutes, and other tribes, he persuaded remnants of his father’s people to join him, and with a band of approximately two hundred he reoccupied the valley, naming himself as chief. These Indians represented a small part of the Interior California Miwoks, which in ancient times numbered in the neighborhood of 9,000, and comprised a group of closely related tribes occupying the western foothills and lower slopes of the Sierra Nevada.

In accordance with Indian tradition, Tenaya’s tribesmen were separated into two divisions-the “Coyote” side and the “Grizzly Bear” side. Outsiders eventually designated the whole tribe as “Yosemites,” which means “Grizzly Bear.” The valley itself remained “Ahwahnee” to the Indians, as it had been so called by the earlier Ahwahneeche inhabitants.

[Editor’s note: for the correct meaning of Yosemite, see “Origin of the Place Name Yosemite”—dea.]

For a few score years Tenaya reigned supreme in “Ahwahnee.” Then in his declining years came the California gold rush. Wherever mining activities flourished, Indian supremacy quickly vanished. Driven from his home, the red man sought another dwelling place, only to be routed out again and again with further aggression of the whites. His final destination was the Indian reservation.

Nearer and nearer came t h e greedy gold-seekers to Tenaya’s domain. Such towns as Mariposa, Mt. Bullion, and Coulterville sprang up with suddenness when gold discoveries drew throngs of white men to their vicinities. While Indians of the foothills made treaties with the whites, many mountain Indians including the Yosemites resented their intrusion. In retaliation and in a futile effort to discourage the white men from further usurping their

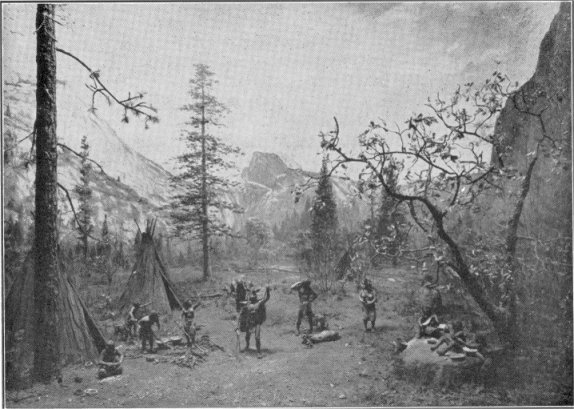

Miniature Indian Village Diarama—Indian Room. Yosemite Museum |

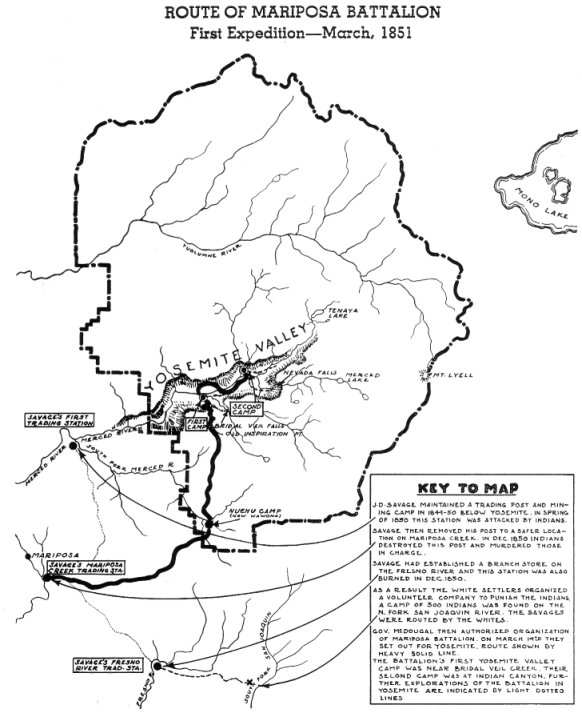

In March, 1851, under the authority of Governor McDougal, the Mariposa Battalion was organized to subdue the Yosemites and their neighboring tribes, and to convey them to the Fresno River Reservation where Indians of the San Joaquin Valley and the coast had already been established by the Indian Commissioners.

James D. Savage, a trader, was elected major of the battalion. Savage had a personal grudge to settle The previous December, his Fresno River store had been attacked by the Indians and destroyed. The two men in charge had been ruthlessly murdered. Simultaneously, his Mariposa Creek Station had been ravaged and three white men killed. Being thoroughly convinced that the Yosemites were the ringleaders in these outrages, Savage vowed he would rout them out to the last Indian from their stronghold where they believed themselves secure, and would bring them to submission either by treaty or force of arms.

After the Mariposa Battalion had surprised and captured an Indian rancheria on the South Fork of the Merced River at what is now called Wawona, Savage sent an Indian messenger ahead to demand Tenaya to surrender, emphasizing that it would be to the advantage of the Yosemites to immediately sign a treaty with the Indian Commissioners to quitclaim their lands, and to leave for the reservation on the Fresno River without resistance.

Francisco, an early day Yosemite in dance costume. (Boysen photo) [Editor’s note: Francisco Georgley, a Chowchilla Indian—DEA] |

Upon Tenaya’s advice, the Yosemites agreed to make treaty, and the old chief himself went on ahead to report to Savage that his people were coming in. Savage waited three days for the fulfillment of Tenaya’s promise, and then suspecting him of deceit, took part of his company and set out toward the valley with Tenaya acting as guide. Following along an old Indian trail in the approximate location of the present Wawona Road, they came mid-way upon a scattered line of seventy-two Indians. There were old squaws, younger women with papooses on their backs, small children, but no braves. All were weary from the long march over and through snow several feet deep. Although Tenaya assured Savage that this group represented his entire tribe, Savage was still suspicious. He sent Tenaya back to the South Fork Camp with the Indians, while he and his soldiers went on in search for the rest of the Yosemites.

Through Savage’s grim determination to rout out the Yosemites from their mountain refuge, Yosemite Valley was first entered by him and his small company of soldiers on March 21, 1851.*

Emerging from the forest, the detachment suddenly came out on a clearing—old Inspiration Point. Revealed in panorama before their eyes was Tenaya’s secret fortress— a gem of a valley, river-ribboned, in a setting of sheer, precipitous, granite cliffs, domes, and spires of surpassing grandeur. What they witnessed had been wrought by millions of years of geologic changes, but history bears record that only one of these rough mountaineers, Dr. L. H. Bunnell, was emotionally stirred by the awe-inspiring view. The thought uppermost was to blot out the Indians who claimed this valley as their own.

That night while Savage and his men chatted around a campfire near Bridalveil Fall, Dr. Bunnell, who was thrilled with the rare scenic value of the valley, suggested that it be called “Yosemite,” after the Indians who were being driven out. Thus Yosemite Valley was entered for the first time by white men and named the same day.

The following day Savage and his men searched the valley floor in vain; they scouted up Tenaya Creek

(*) Actual discovery of Yosemite Valley occurred at an earlier date. In the fall of 1833 a party of approximately 40 men, under the leadership of Joseph Reddeford Walker, passed through the area now included in Yosemite National Park. This journey was memorable in that it represented one of the first crossings of the Sierra Nevada. Members of the Walker party were thus the first white men to enter the area now included in Yosemite National Park.

Unfamiliarity with the region, its rugged terrain, and the season’s lateness combined to make their journey through this region a long and extremely arduous one. Records indicate that members of this group, in scouting for a suitable westward route through the mountains, first saw the Valley from a point on the north rim. However, the Walker party never entered the Valley and their discovery made no great impression upon them. Thus this fact was not fully substantiated until comparatively recent years. In consequence, the existence of Yosemite Valley was generally unknown in 1851 when it was first entered by the Mariposa Battalion, although certain Indians had hinted of the presence of a formidable mountain refuge on several occasions co-incident with the Indian troubles of that period. (See “Narrative and Adventures of Zenas Leonard,[”] edited by M. M. Quaife, Lakeside Press, Chicago, 1934; also Walker’s Discovery of Yosemite, Francis P. Farquhar, Sierra Club Bulletin, Vol. XXVII, No. 4, August 1942),

[Editor’s note: today historians generally believe the Walker party looked down The Cascades, which are just west of Yosemite Valley, instead of Yosemite Valley itself.—dea]

|

Savage soothed his disappointment and failure by burning the dwellings, large caches of acorns and other provisions the Indians had left behind.

Although they were the first to enter Yosemite Valley, and were responsible for its name, this expedition of the Mariposa Battalion did not accomplish its purpose: i.e., to exterminate the Indians. Through carelessness of the guards in charge, tricky Chief Tenaya and his entire people were able to delay their relegation on the Fresno River Reservation by escaping during the night.

Three Brothers, named for sons of Chief Tenaya |

The second expedition against the Yosemites took place in May, 1851, under command of Captain John Boling, whose company was a part of the Mariposa Battalion.

At the outset, five Yosemites were captured, three of whom were Chief Tenaya’s sons. Of these captives, Captain Boling released one of Tenaya’s sons and his son-in-law, under promise that they would bring in the old chief so that treaty might be made; the other three were held as hostages.

The soldiers in Captain Boling’s camp practiced archery with the three remaining prisoners, and one of the captives shot his arrow far beyond the others. He was allowed to search for it, but the opportunity for freedom was so overpowering that he took a chance and darted off. The other two prisoners were then tied back to back and fastened to a tree. Later they were able to unfasten the ropes that bound them, but when attempting to slip off, the guard discovered them and fired. Tenaya’s youngest son was killed; the other Indian managed to escape into Indian Canyon.

A short time after this unfortunate episode, Tenaya entered Boling’s camp to surrender, and great sorrow confronted him. Before him on the ground lay the lifeless form of one very dear to his heart—his youngest and most beloved son. Captain Boling’s regret did not in any way alleviate Tenaya’s grief. He stood in repressed anguish, facing not only the death of his son, but the end of his liberty and happiness. A few days passed, and when Tenaya’s people failed to join him in surrender, he too attempted escape, but was caught by Captain Boling just as he was about to plunge into the river. In a state of utter failure, mental anguish, and grief he piteously begged Captain Boling to kill him as he had killed his son, but warned him that his spirit would return to torment the white man.

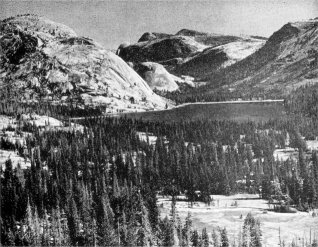

Captain Boling continued his pursuit of the remainder of the Yosemites into the snow-clad high country, and with his soldiers surprised them as they were encamped on the shores of Tenaya Lake. The Indians, realizing that resistance was futile, surrendered. Records state that so anxious was Captain Boling to advance upon the Indians when their camp was discovered that he did not allow his soldiers sufficient time to don their uniforms. They were given the command to march four miles over and through ten feet of snow stripped to their red flannel underwear.

In 1928, old Maria Lebrado, the last of Tenaya’s people, described this incident as seeing “lots of red.”

Subsequent to the success of the second Yosemite expedition Tenaya and his people were assigned to the Fresno River Indian Reservation along with many other subdued tribes. Here, Tenaya chafed miserably under restraints placed upon him, and was unable to adapt himself to his new environment. After constant appeals, the Indian Commissioners permitted him to return to Yosemite Valley under promise that he would provoke no more trouble. Tenaya was soon joined in his old stamping grounds by other Indians of his tribe who managed to escape from the reservation. The winters of 1851 and 1852 passed and Tenaya kept his promise to the commissioners by causing no disturbances. In May 1852, a party of eight prospectors fearlessly entered Yosemite Valley with no idea of trouble with what they supposed were peaceable Indians. To their utter horror and astonishment the Yosemites made an unexpected and vicious attack. Two of their number were brutally murdered and the others barely escaped with their lives.

As the Mariposa Battalion had been disbanded, a detachment of the regular army was immediately sent into the valley from Fort Miller to forestall further trouble. Five Indians

Tenaya Lake, named for Chief Tenaya, last chief of the Yosemite. |

In the late summer of 1853, old Chief Tenaya and his small group of followers returned to Yosemite Valley for the last time. Having no horses of their own for meat, they treacherously stole a number belonging to the Monos. When this theft was discovered by the owners, they at once made ready to pursue Tenaya, and to administer revenge for this gross expression of ingratitude. While Tenaya and his band sat around a campfire enjoying a feast, the Monos suddenly swept down upon them. One Mono Indian hurled a rock directly at Tenaya’s head, which crushed his skull. For the old chief, who had escaped death so many times, there were final darkness and oblivion. The Monos killed all of Tenaya’s followers, except a few women and children, one of whom was Maria Lebrado. In 1928, Dr. Carl P. Russell, at that time Yosemite’s Park Naturalist, interviewed aged Maria Lebrado as the only living survivor of Tenaya’s people.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_indians/history.html