[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Nature Notes > 47(3) > The Mountain Duck >

Next: Plate Tectonics • Contents • Previous: Table of Contents

Bill Dengler

During late May, 1977, reports were received of a curious duck bobbing about on the South Fork of the Merced River near the Pioneer Yosemite History Center. One observer said that it looked like a small Canada Goose but with very faint markings. The bird was verified on June 22 as a female Harlequin Duck, rare now, but apparently once fairly common on swift streams in the Sierra Nevada.

A check in Birds of North America shows that the Harlequin Duck, Histronicus histronicus pacificus, is a sea duck whose Western range is centered along the coast of Canada and Alaska. Its habitat is described as swift rivers and arctic shores during summer and heavy surf along rocky coasts in winter. Curious strands of summer range project inland from the Pacific Ocean. Thus, our sea duck may prefer to summer in the mountains!

Sightings of Harlequin Ducks in the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountains were first reported in the late 1800s. Belding saw many Harlequin Ducks on the principal streams of Calaveras and Stanislaus counties during the late 1870s. He shot a juvenile and sent it to the Smithsonian Institution in 1879 or 1880 (Dawson, 1923). Dr. E.W. Nelson and Major Bendire submitted other early reports in 1887 and 1898 respectively (Bent, 1925). Belding states that fishermen killed many, and the ducks were greatly reduced in numbers even within his time. The loss was due to a very unfortunate misconception as the ducks rarely if ever take fish.

The earliest sighting recorded in Yosemite National Park was made on May 2, 1915, when six Harlequin Ducks were observed on the South Fork of the Merced River just below the Wawona Fish Hatchery (Newsome, 1915). The next record, and the first for Yosemite Valley, was in April, 1916, when one individual

[click to enlarge] |

After 1927, there is a gap of 13 years before a female was sighted near Wawona on October 20.1940 (Grinnell and Miller, 1944). This apparently is the only fall observation recorded in the Sierra. After this single encounter, another 32 years elapsed until April 9, 1972, when two observers named Herbert and Gerughty sighted a lone male on Tenaya Creek, 1/4 mile below Snow Creek. The next observation reported was the female at Wawona in 1977.

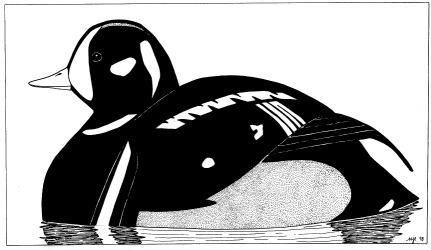

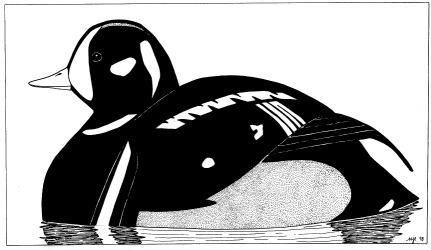

The male Harlequin cannot be confused with any other duck. His basic color is gray, with random splotches of white and black and chestnut sides. One legend holds that the male Harlequin Duck was initially gray. Being dissatisfied with his drab color, the duck asked Mother Nature for some brighter trim. She complied with his wish and hurriedly dabbed splotches of white, black and chestnut here and there, transforming the male gray Harlequin into one of the most wildly colored of ducks. In contrast, the female is a blend of light and dark browns with three faint white patches on the head.

The color and habitat of the Harlequin Ducks have led to a number of appropriate synonyms. Among these are Lord and Lady, Painted Duck, Rock Duck and Mountain Duck.

Dr. Paul A. Johnsgard describes the breeding distribution and habitat of Harlequin Ducks as “curiously disruptive.” The primary breeding center is in the forested mountains of western North America with a smaller, secondary population in northeastern North America. The major center is to the north, including coastal Alaska and the Aleutian Islands inland to the Brooks Range and in Western Canada including much of British Columbia and Western Alberta. South of Canada the Harlequin Ducks are confined as breeding birds to the Western mountains. Frequency declines as one moves south with breeding birds commonest in Washington, then Oregon, then California. Some birds move inland into the Northern Rocky Mountains as far as Yellowstone National Park, but apparently not into Colorado (Johnsgard, 1975).

California is the southern extension of the Harlequin Duck’s range in both summer and winter. The mid Sierra Nevada marks the southern extent of the summer range and a sighting at Playa del Rey south of Santa Monica on December 22, 1946, marked a new southern range extension at that time (Kent, 1947).

The preferred breeding habitat is a cold, rapidly flowing stream frequently, but not always, surrounded by forests. Breeding may take place near saltwater, especially in the north, but is apparently always accomplished on a freshwater stream. Nests are located on the ground close to the water_ The clutch of 4-8 eggs is well concealed by dense vegetation. Predation on nests is apparently low due to the location of the nest and the ability of the ducklings to successfully hide in the grass.

The male appears to desert the female shortly after incubation begins, yet there are very few sightings of Harlequin Ducks between the Sierras and the coast. The first such sighting was recorded on January 4, 1948 a male at the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge (Dehnel, 1948)

Both sexes winter along the coast, usually in rocky areas of rough surf. During all seasons the Harlequin Ducks prefer fast-moving, rough water

Feeding is accomplished by diving or dabbling, depending upon the depth and speed of the water. The ducks show no preference for deep water but readily wade-about in shallows and walk or stand on rocks or logs. Michael (1922) states that Harlequin Ducks walk about on the bottom like a Dipper, moving against the current. Both the wings and feet are used to reach the bottom, then the wings are closed as the bird uses the force of the current to keep it submerged. After remaining submerged for 15 to 25 seconds the duck bobs to the surface like a bubble, where it resumes swimming to remain stationary or to move against the current.

To move downstream the ducks simply relax and float with the current, bobbing along, occasionally through some rough water. Upon reaching the desired location, paddling is resumed and control quickly regained as they move about facing the current.

Food varies with the season and habitat. Johnsgard (1975) lists the winter food as 57% crustaceans, 25% mollusks and 10% insects. Decapods (e.g., smaller crabs) and soft-bodied crustaceans (e.g., amphipods and isopods) are apparently favored and comprised half the volume of the samples analyzed. During the summer, insect species typical of rapidly flowing streams (i.e., stone flies, water boatmen and midge larvae) were more prevalent.

Although the Michaels never observed the Harlequin Ducks eating natural vegetation, the birds readily ate vegetables from a tray floated in the river to lure them into camera range. Food items accepted from the tray included cooked potatoes, macaroni, meat, raisins and bread. They never observed the ducks eating fish or any large object, and speculated correctly that their major food was aquatic insects.

The female on the South Fork of the Merced River during the summer of 1977 was last observed on July 28. Interestingly, July 28 was the last day the Michaels saw the birds they were observing in Yosemite Valley in 1921. Probably, declining water level forces the birds to depart for the coast by mid-summer. Although 1977 was a very dry year, isolated rapids and meager pools of water remained into mid-July.

Undoubtedly there are many, many miles of remote Sierra streams on which the Harlequin Ducks may still be found. However, from the recorded observations, it appears that the number of these little ducks in the Sierra has declined drastically over the last 100 years.

So, strange as it may seem, sea ducks are numbered among the wildlife one may encounter in the Sierra Nevada. They are one more species to be alert for while exploring the wonders of Yosemite.

Bent, Arthur Cleveland. LIFE HISTORIES OF NORTH AMERICAN WILD FOWL. U.S. National Museum Bulletin #130. pp. 58-62. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1925.

Dawson, William Leon. THE BIRDS OF CALIFORNIA. Vol. 4, pp. 1825-28 South Moulton Co., 1923.

Grinnell, Joseph and Alden H. Miller. THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE BIRDS OF CALIFORNIA. Cooper Ornithological Club, Pacific Coast Avifauna, No. 27, pp. 87-88, 1944.

Grater, Russell. Bird Records Compiled by Russell Crater, Summer 1943. On file at Yosemite Research Library.

Johnsgard, Paul A. WATERFOWL OF NORTH AMERICA. Indiana University Press, 1975. Kent, W. A. “Harlequin Duck near Los Angeles, California” THE CONDOR, Vol. 49, No. 3, p. 132. May, 1947.

Newsome, J.E. “Harlequin Ducks in the Sierras in 1915”. California Fish and Game. Vol. 1, No. 5, p. 237. October, 1915.

Robbins, Chandler S., et. al. BIRDS OF NORTH AMERICA. Golden Press, New York, 1966.

Next: Plate Tectonics • Contents • Previous: Table of Contents

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_nature_notes/47/3/mountain_duck.html