[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Nature Notes > 47(3) > Trail Erosion in Mountain Meadows >

Next: Mono Pass & Bloody Canyon • Contents • Previous: Stock Use

Jim Snyder

Trails formed in Yosemite meadows for the simple reason that open meadows offer easy access and a place to get one’s bearings and survey the country. Ruts developed in some boggy areas around the turn of the century, but the problem was usually confined to small areas, stirring no complaint. After World War II, when backpacking began to increase rapidly, the problem of multiple trails through meadows became severe.

Though rut scars on high mountain meadows have been most often attributed to stock — and, indeed, recreational stock-use earlier in the century probably contributed to present rut formation — foot travel early in the season has been the largest cause of trail erosion. The reason is timing. When meadows are still wet, in the spring and early summer, they are ill-prepared to withstand the use they receive. Spring travellers walk on grass which has not yet had a chance to establish itself in soil still loose and mushy from the year’s runoff. It does not take much to crush and churn the sod until a path is formed not only for hikers but for the runoff itself. Once the trail becomes a water channel too, then water can, with the aid of people, cut through the sod and begin to rut and gully the meadow.

A trail rut acts as a runoff channel, gathering the meadow runoff and directing it. Early in the season, then, meadow trails often fill with water. To keep their boots dry, hikers step up on the grass along the trail’s edge. Soon another path forms which also begins to rut. In a decade, a meadow trail may become six or eight lanes at places wet and boggy during April, May, and June. Resulting erosion varies greatly with soil, vegetation, and drainage pattern.

Popular solutions to meadow erosion from trails have been 1) to limit stock use, and 2) to reroute trails around meadows. The impact of stock in Yosemite’s backcountry in the past has been greater in grazing than in trail use. Proposals to limit stock use to solve meadow trail erosion problems have not taken into account pressures applied by foot travelers. The problem of erosion is not a matter of one mode of transportation compared with another so much as the patterns of use and relative numbers involved at critical times of the year.

Private stock use i n Yosemite has declined since World War I I as pack stations on the east and west sides have gone out of business. Though the number of privately owned horses in California has grown by many thousands in the last two decades, that increase has not been reflected in backcountry stock use, which is, in large part, confined now to concession operations along the High Sierra Loop and government backcountry maintenance and patrol. The latter stock is not present in the backcountry normally before the end of June or early July and then only for about two and a half months. Stock impact, as a result, has been limited naturally by economic changes in recreation patterns.

The building of reroutes around meadows has had effects opposite to original intentions. Reroutes, far from reducing impact, have in fact doubled the damage to local environments. There are two major reasons for this. First, the planning for reroutes failed to account for the reasons trails went through meadows. Late melting snows most often constrict travel in areas such as Rafferty Meadow to the meadow itself well into June. Since the Rafferty reroute was never blazed (that mountaineer’s practice having been discontinued since the early 1950’s), the only guide to the reroute early in the year is the Vogelsang phone line, along which more than one party has lost its way. The meadow is more direct; certainly meadows are more scenic. Meadow trails continue, therefore, to draw considerable traffic.

Second, reroutes failed because their construction included no real effort to fix the original meadow damage simultaneously. Signs prohibiting use on the old Rafferty Meadow trail are widely ignored, and the gullying of that meadow would continue even if they were not. Efforts to stop gullying on the old Soda Springs-Glen Aulin trail were based on an assumption that the ruts could fill in by themselves, but they cannot without a source of sod or fill. In these two cases, the reroute trails were laid out poorly, without adequate drainage or tread preparation, so that the reroutes also have deteriorated with heavy use. The policy of rerouting around meadows, as a result, has not stopped or even slowed meadow trail erosion, while the reroute practice has spread erosion to include forest as well as meadow areas.

Rerouted trails are rarely necessary. Work should be concentrated most often on repairing the old trail correctly in the first place. That was how trail crews came up with a solution for the meadow trail erosion problem. Tuolumne Pass below Vogelsang was the site for the first meadow project during August, 1975. Crews completed a second meadow project at the slick rock three miles below Soda Springs on the Glen Aulin trail in September, 1976. Their method is relatively simple. It developed after four seasons of rebuilding the Merced River canyon trail through several different environments.

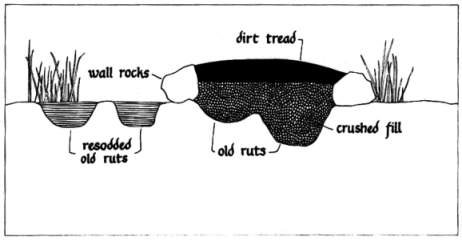

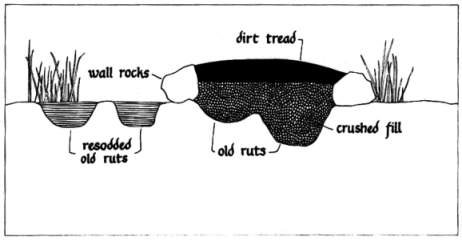

A cross section of a meadow trail causeway looks like this:

[click to enlarge] |

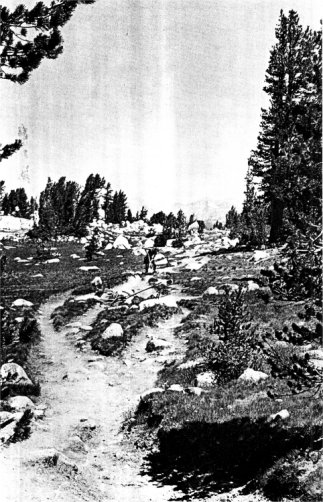

[click to enlarge] The trail at Tuolumne Pass before work, early August, 1975. |

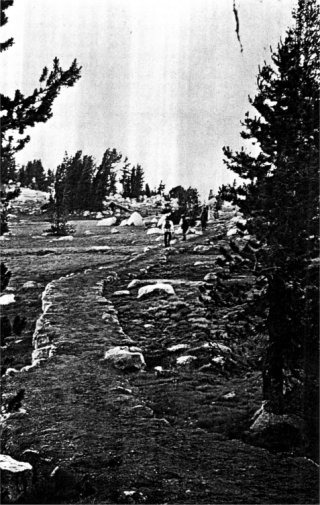

[click to enlarge] The same trail with causeway and new sod in late July, 1976. |

A causeway is laid through the widest and deepest ruts, leaving other ruts to be resodded later. Walls about ten inches higher than the meadow surface hold a fill of crushed granite, which fills in the old ruts but keeps the trail itself porous for drainage. On top of the fill is laid a tread of dirt, packed in by mule, and the compacted soil is removed from the ruts to be resodded.

Trail crews attempt to do sections of the meadow causeway in sequence from start to finish so the finished trail can be used to haul materials through the meadow for each successive section. That reduces impact on the meadow from the construction, as does working the site late in the season when the meadow is dry. When the trail itself is done, the remaining ruts are resodded, using sod containing species of plants identical to those of the meadow, taken from far off the trail in an area with a demonstrated rate of rapid recovery Crews currently are working on a means to eliminate transplanting altogether by producing meadow turf artificially for resodding old ruts.

Because the work includes as much effort in restorative camouflage as it does in acutal construction, the signs of construction have nearly disappeared by now. The dirt pit at Tuolumne Pass is a gentle swale of lupine and grass. The sod strips are coming back more slowly, but new grass is growing into them. The pulling mules, Katie and Belle, hauled tons of rock over the meadow grass with a stoneboat, a large, flat piece of steel with broad runners to distribute the weight of the load widely over the ground with little impact. This stoneboat, discovered in the Merced River by Bill Sabo, had been used in the building of the El Portal Road in the 1920’s, but the technique had been all but lost in Yosemite since that time.

The results at Tuolumne Pass are apparent in the photographs of the trail before work started and the same trail a year after the causeway was finished. The new sod has taken hold.

Though it is still too early to tell, the research done by John Schelhas, a trail crew member and botanist, on the relationship between trail erosion and meadow vegetation suggests that the meadow causeway has made it possible for some species sensitive to trampling to give up their retreat from the trail and finally return to its very edge. The causeway, it seems, has permitted the meadow to work as a meadow once more. Trail erosion has been eliminated, and hundreds of people still can use the meadow route to get where they want to go.

Next: Mono Pass & Bloody Canyon • Contents • Previous: Stock Use

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_nature_notes/47/3/trail_erosion.html