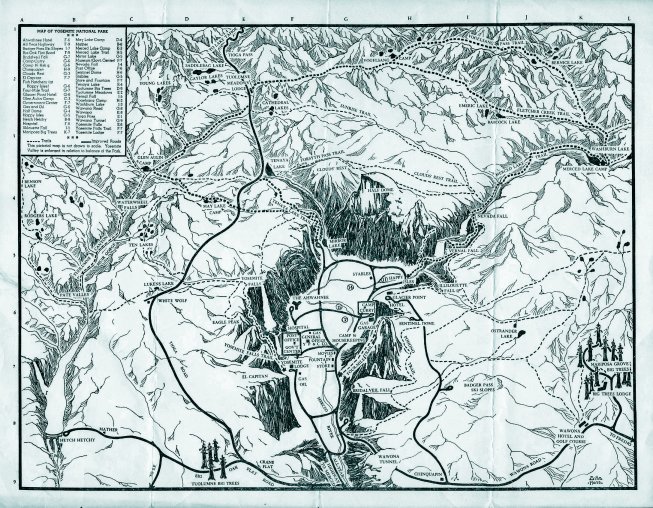

Map of CCC camp no. 1, Wawona, 1934.

NPS, Denver Service Center files.

[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Resources > Chapter VI: National Park Service Administration, 1931 to Ca. 1960 >

Next: 7: Historical Resources • Contents • Previous: 5: NPS 1916-1930: Mather Years

A. Overview 731

1. Stephen Mather Steps Down 731B. Roads, Trails, and bridges 758

2. Public Works Programs Aid Completion of Park Projects 732

3. The Dissolution of Emergency Relief Projects Severely Impacts Park Conditions 750

4. MISSION 66 Revives Park Development 752

1. Trail Construction in the early 1930s Results in Completion of John Muir Trail 758C. Construction and Development 802

2. Reconstruction of Park Roads Begins in early 1930s 762a) Paving and Tunnel and bridge building Commence 762

b) Tioga Road 762

c) Wawona Road and Tunnel 763

d) Yosemite Valley bridges 769

e) Glacier Point Road 769

f) Big Oak Flat Road 771

g) Trail and Road Signs 771

h) Bridge Work Precedes Flood of 1937 778

i) North Valley Road Realignment Considered 784

j) Completion of New Big Oak Flat Road 785

k) Bridge Work Continues in the 1940s 785

I) Flood of 1950 795

m) Completion of the Tioga Road 796

n) Flood Reconstruction Work Continues 797

o) MISSION 66 Provides Impetus for New Big Oak Flat Entrance Road 802

1. Season of 1931 803D. Concession Operations 884

2. Season of 1932 811

3. Season of 1933 815

4. Season of 1934 824

5. Season of 1935 839

6. Season of 1936 850

7. Season of 1937 851a) General Construction 8518. Season of 1938 855

b) Flood Damage 852

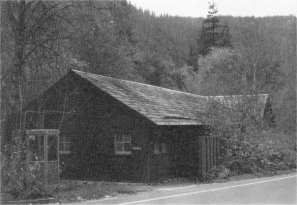

c) New CCC Cascades Camp Constructed 853

9. Seasons of 1939-40 859

10. Period of the Late 1940s 871

11. The 1950s Period Encompasses Many Changes 872

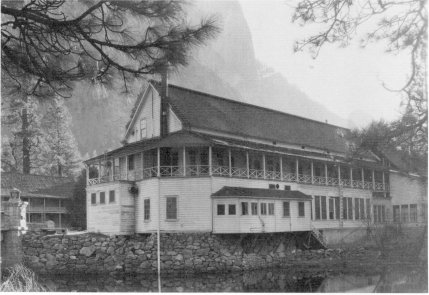

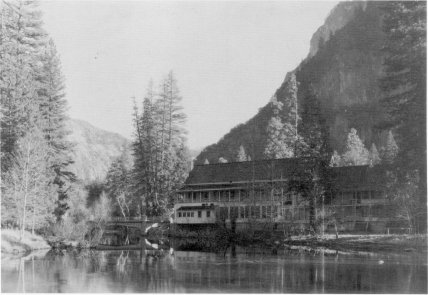

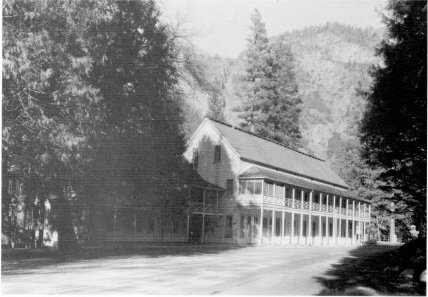

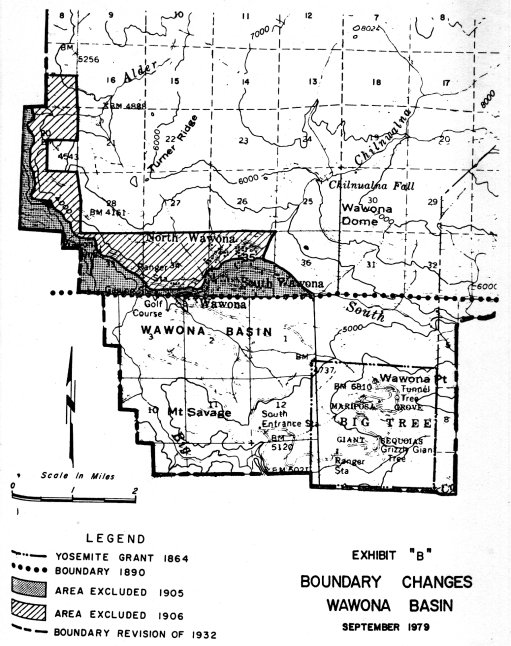

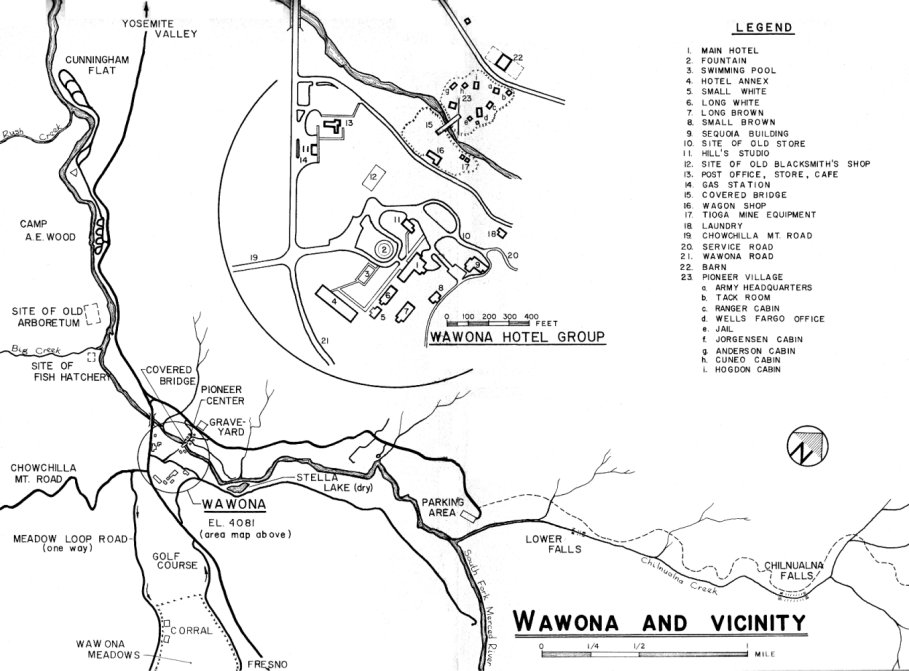

1. The National Park Service Acquires Wawona Basing 884E. Patented Lands 917

2. Big Trees Lodge 894

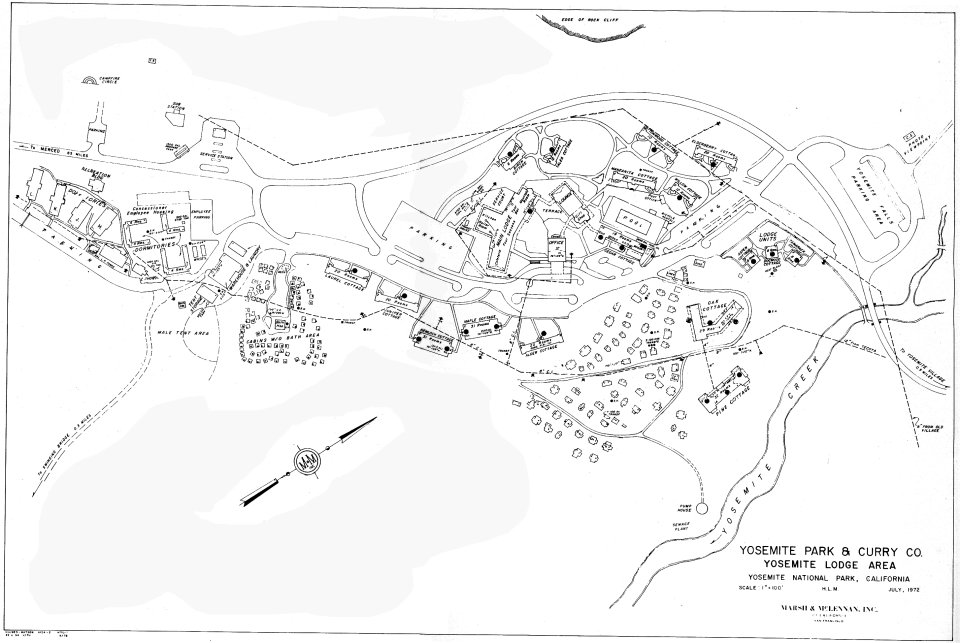

3. Chronology of Later Yosemite Park and Curry Company Development 895a) Company Facilities Need Improvement 895

b) Winter Sports Move to Badger Pass 901

c) Limited Construction Occurs 902

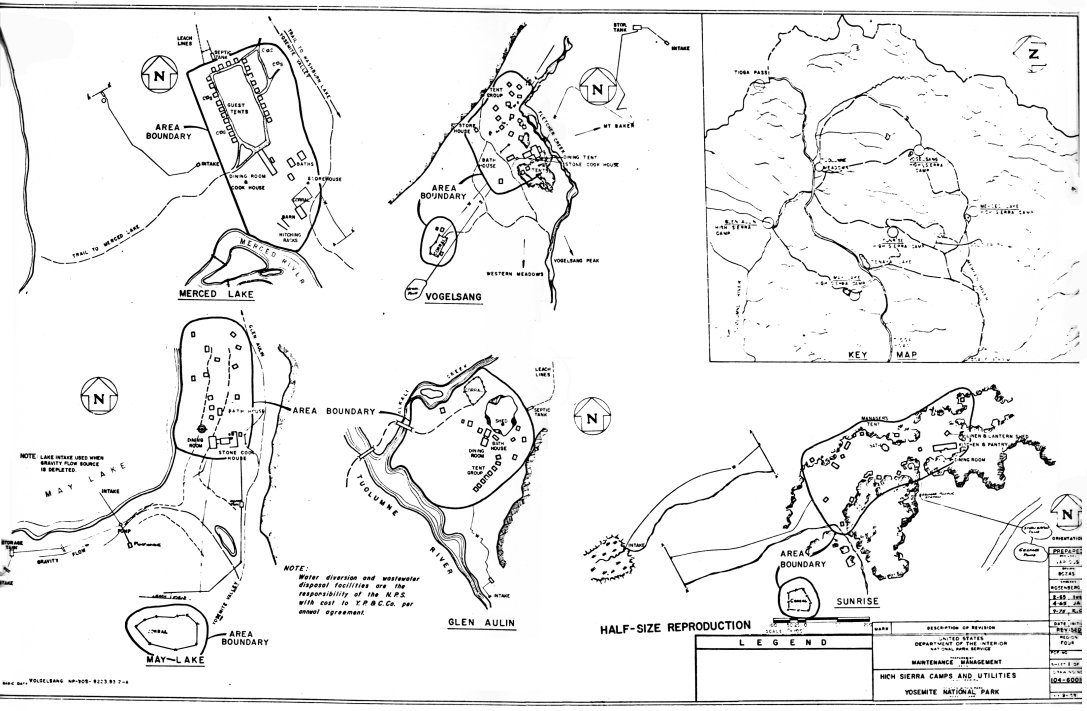

d) High Sierra Camps Continue 903

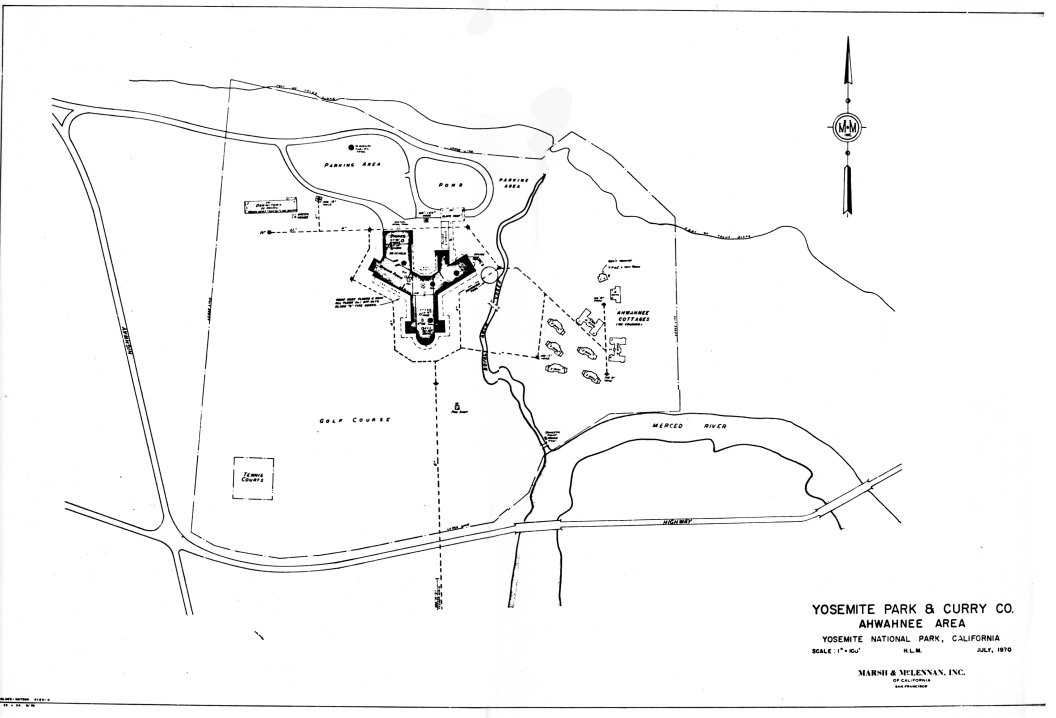

e) the U. S. Navy Takes over the Ahwahnee Hotel 904

f) The Curry Company Begins a New Building Program 905

1. Remaining in 1931 917F. Hetch Hetchy 948

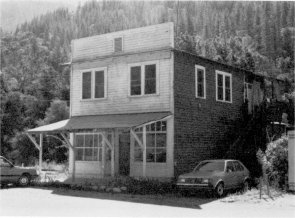

2. Yosemite Lumber Company 922

3. Section 35, Wawona 923

4. Camp Hoyle 931

5. Hazel Green 931

6. Carl Inn 932

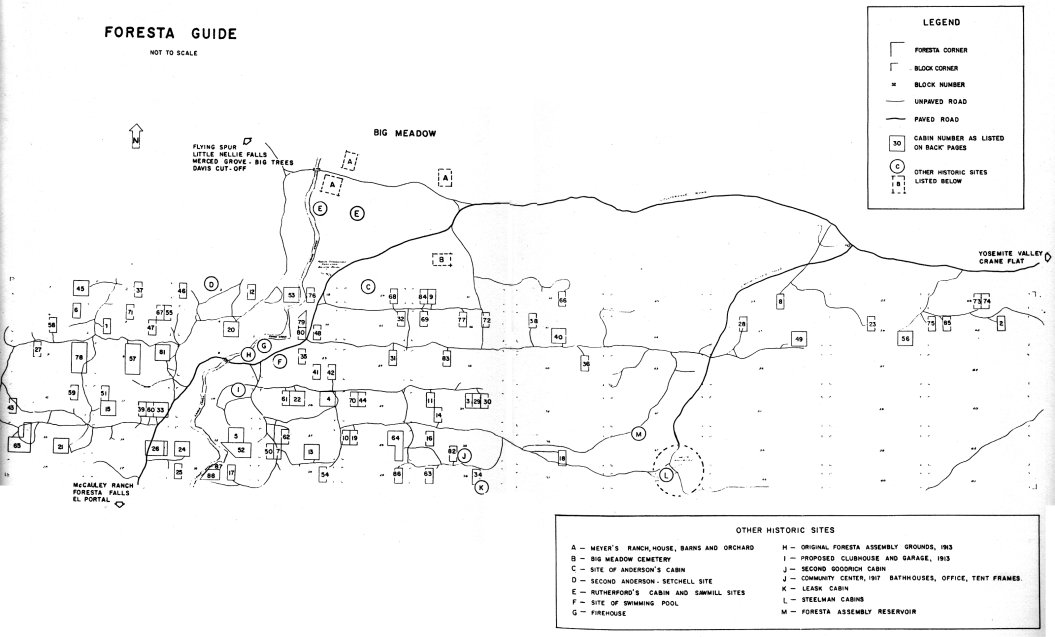

7. Foresta 932

8. Big Meadow 937

9. White Wolf 938

10. Soda Springs 939

11. Tioga Mine 944a) Renewal of activity 94412. MISSION 66 Provides Impetus for Land Acquisition 947

b) Mine ruins 946

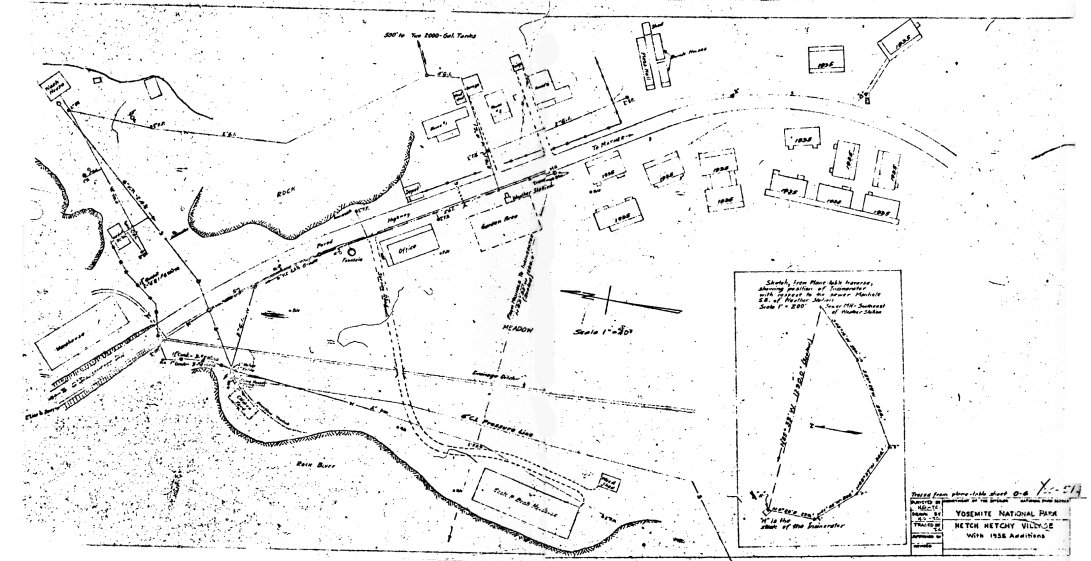

1. O’Shaughnessy Dam Raised 948G. Yosemite Valley Railway 961

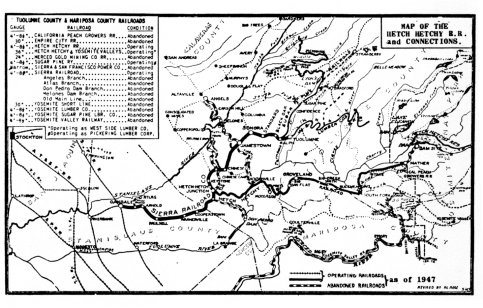

2. Hetch Hetchy Railroad Revived 949

3. Construction and Security, 1930s-1950s 961

1. River and Stream Control 967J. Fish and Game 981

2. Fire Control 974

3. Grazing 975

4. Insect Control 977

5. Blister Rust Control 979

1. Stephen Mather Steps Down

The period covered by this chapter offered strong challenges and an exciting future to the National Park Service. After struggling to build a foundation for America’s park system based on sound policies and broad principles of resource conservation and park protection during the difficult years of World War I and its aftermath, the Park Service was well on the way to achieving its desired goals when two potentially devastating events took place.

In January 1929 Stephen Mather stepped down as director of the Park Service due to ill health, which resulted in his death in January 1930. The loss dealt a severe blow to the park system in America to which Mather had contributed so much time, effort, and money in an attempt to establish a solid and organized management system with a clear philosophical direction. Fortunately, Mather’s ideals and basic policies continued under Horace Albright, who, because of his long tenure with the Park Service, dating from before Mather’s time, and years of assisting Mather, made him practically a co-founder of our present National Park System.

Having functioned as Mather’s assistant for so many years in addition to serving as superintendent of Yellowstone for ten years, Albright could smoothly continue building on the achievements of the early Mather years. He was knowledgeable in governmental affairs and well-known and respected in Washington’s political arena. Of great benefit to his work was the fact that the park idea had become solidly entrenched in the American consciousness. Albright also enjoyed the support of Interior Department officials and the aid of a first-class staff in the Washington office and in the field. During his four-year tenure as director, Albright enlarged nine of the national parks, including Yosemite, and also gained three additional parks as well as several national monuments.

The biggest challenge facing Albright almost immediately involved the economic and social crises occasioned by the American stock market crash and the arrival of the Great Depression. With organizational skill and a masterful grasp of problems and solutions, Albright successfully guided the National Park System through this critical period and into the early part of the New Deal. Albright assumed the Park Service directorship just as Herbert Hoover was assuming the office of President of the United States. During Hoover’s administration the pall of the depression spread over the country, manifesting itself in long food lines, abandoned factories and businesses, rampant unemployment, and bank closures. The nation seemed headed toward complete devastation, with no means in sight of alleviating the distress.

2. Public Works Programs Aid Completion of Park Projects

In 1933, however, Franklin Delano Roosevelt became President and immediately proposed a revolutionary legislative and social program designed to ameliorate the country’s economic situation. Between 9 March and 16 June 1933, Roosevelt proposed fifteen emergency acts destined to dramatically affect the nation’s social and political institutions for years to come. Elated at being presented with constructive legislation, Congress passed them immediately.

Roosevelt’s first concern involved the rampant unemployment in the country, especially among young people who remained unable to find jobs and who were gradually becoming embittered at their fate. Roosevelt perceived that family incomes had to be restored and the morale of young Americans raised at the same time. In his first hundred days in office Roosevelt introduced the idea of a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a program stimulated by his interest in forestry and conservation. The CCC work program, directed by the Emergency Conservation Work organization, received top priority in the early New Deal period. The act establishing the CCC became law on 31 March 1933, enabling the government to take thousands of unemployed young men off the streets and provide them with jobs and a cash allowance, in addition to board, medical attention, educational opportunities, and practical job training. In return, the men performed needed work in America’s federal and state forests and parks.

As the Interior Department’s representative on the CCC Advisory Council, a body composed of representatives of the departments of War, Labor, Interior, and Agriculture, Director Albright immediately began compiling estimates for road and trail work, physical construction, and forest protection and cleanup in the national parks. Because each park already had a master plan for development work, the Park Service was better prepared than most agencies to begin projects immediately.1 The council in the early weeks of the New Deal helped set up the CCC organization and programs and determine the role of participating agencies. The Department of Labor would select the CCC candidates, the army would transport the men to the camps, feed and clothe them, carry out their physical conditioning, maintain morale, and generally handle all camp matters, while the agencies of the departments of Interior and Agriculture for which the men worked would have technical supervision of them during work details.2

[1. Master plans are comprehensive land plans containing basic data relevant to specific park areas. They consist of maps and documentation describing the natural and cultural features, engineering aspects, road systems, -forest fire protection, maintenance problems, and all development that needed to be considered in planning for the area’s protection and public use. Conrad L. Wirth, Parks, Politics, and the People (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980), 58.]

[2. James F. Kieley, CCC: The Organization and Its Work (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1938), 6-7.]

The federal government never considered the CCC a permanent measure, although many who saw its benefits, including Roosevelt, pushed for its continuation as a permanent organization. Entirely financed by emergency funds, it was organized within weeks, the Park Service having seventy camps in full operation by 30 June. The peak of CCC growth came in 1935 when more than 2,500 camps operated. The number gradually decreased up to World War II.3

[3. Wirth, Parks, Politics, and the People, 105; Kieley, CCC, 14.]

The emergency legislation passed in Roosevelt’s first hundred days, providing massive amounts of money and labor, enabled the Park Service to launch several long-term development projects that had been slowly dying for lack of money. The park projects undertaken were selected from each park’s development program. The CCC initiated the largest construction program ever undertaken in Yosemite, but other emergency and relief programs of benefit to the park were also enacted during the New Deal period. Civil Works Administration (CWA) activities took place between November 1933 and April 1934. This program also functioned as an emergency unemployment relief program, created to offset the lull in the business revival of mid-1933 and to soften economic hardships during the winter of 1933-34. It employed men and women in park development projects and used skilled workers as well as artists, painters, sculptors, and draftsmen.

The Public Works Administration (PWA) assumed the continuation of road and trail construction and other physical improvements and, because it necessitated topographical surveys, landscape studies, and wildlife protection policies, provided work for engineers, landscape architects, artists, and scientists. Beginning in 1935, the Park Service cooperated with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) established by the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935, assuming responsibility for techncial supervision of its programs, involving resource conservation and recreational development. Although most of its projects needed manual laborers, arts projects enabled hiring of writers, actors, musicians, and artists. At the start of 1937, the various public works programs undertaken within the National Park System consolidated as Emergency Relief Act 4 Projects until 1941, when public works appropriations began to dwindle.4

[4. Harlan D. Unrau and G. Frank Williss, Administrative History: Expansion of the National Park Service in the 1930s (Denver: National Park Service, 1983), 94-101.]

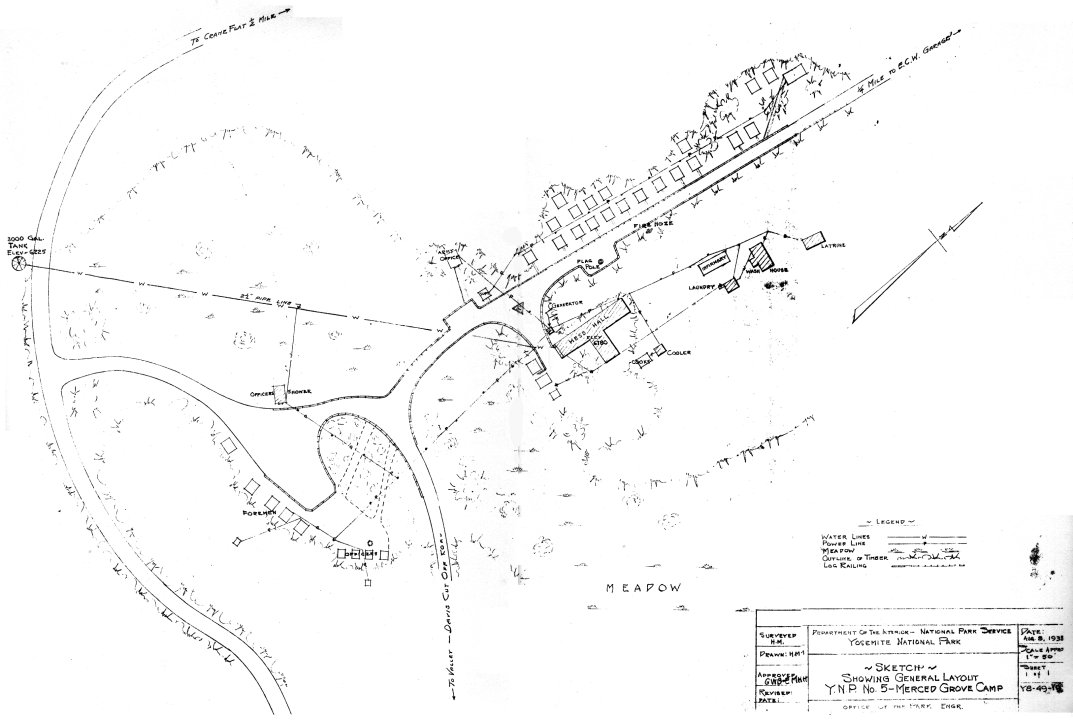

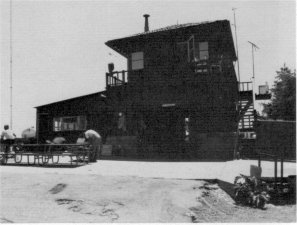

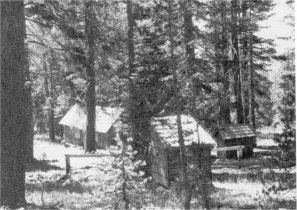

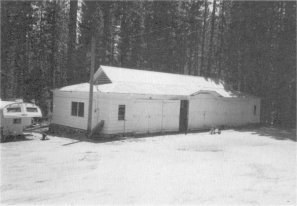

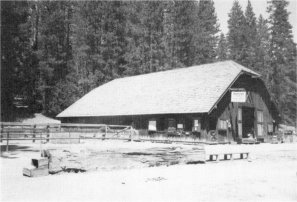

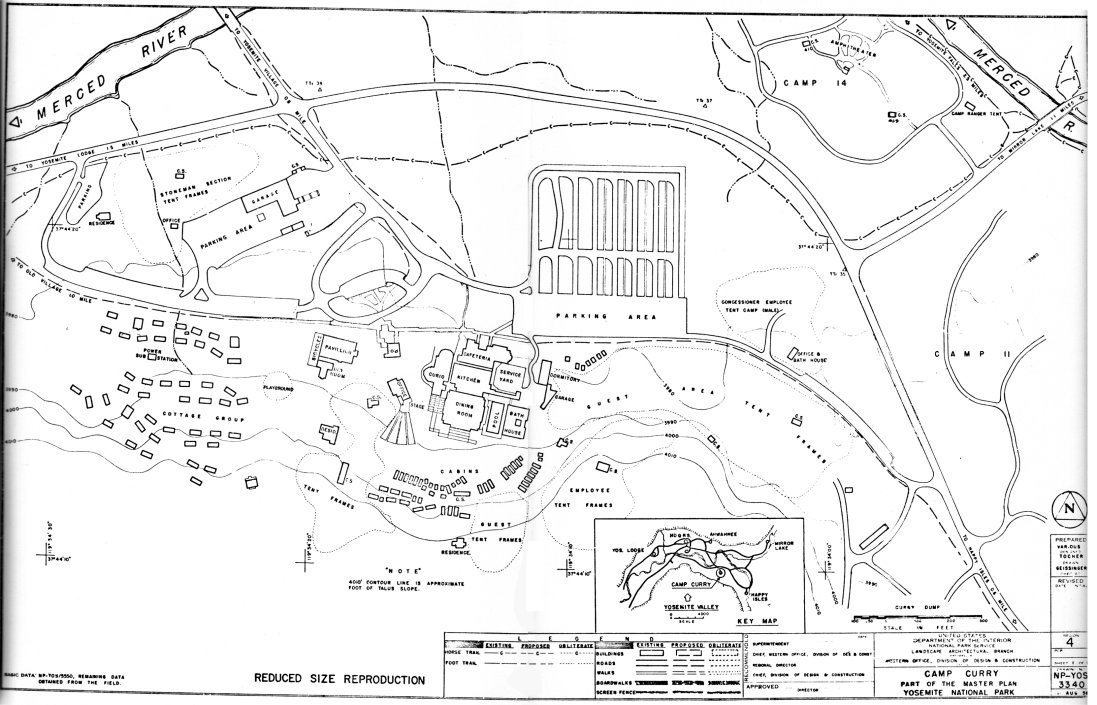

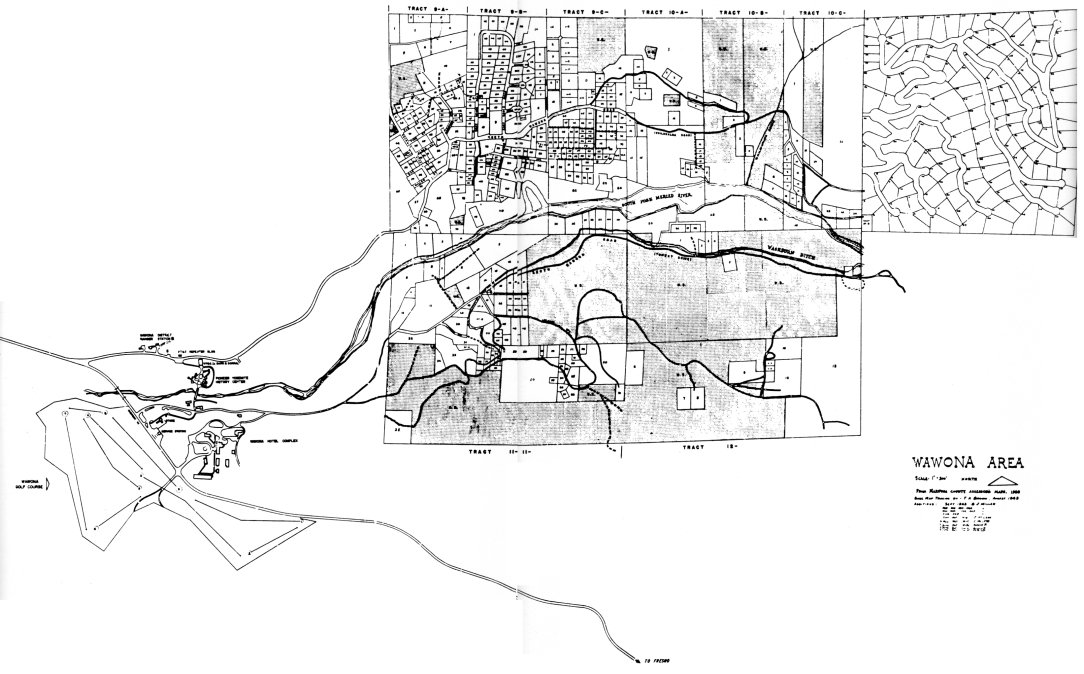

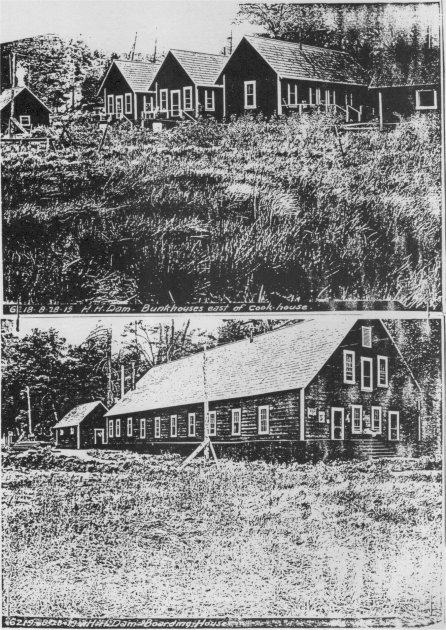

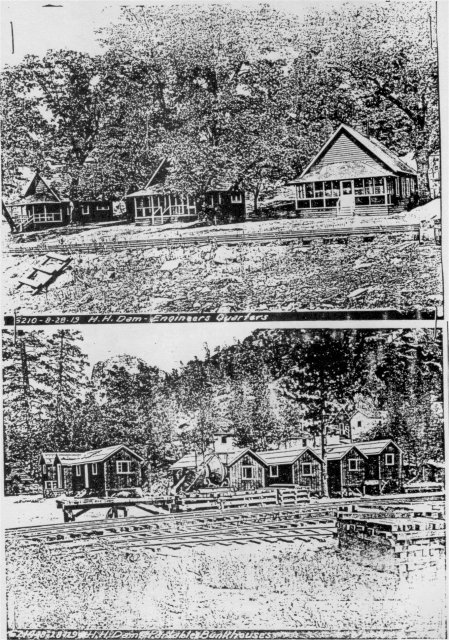

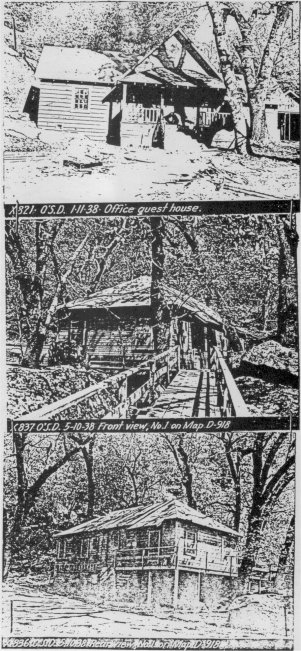

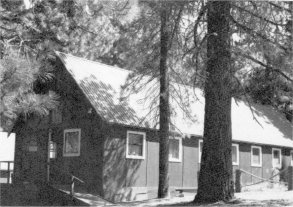

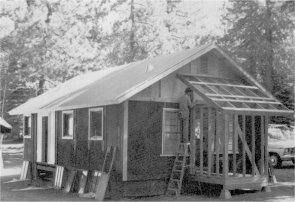

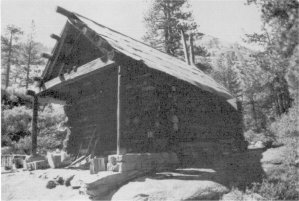

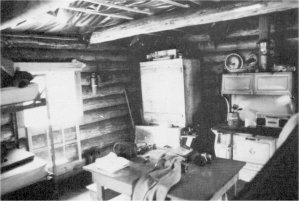

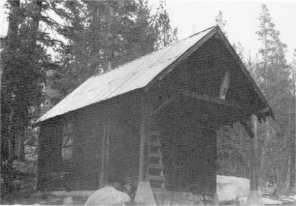

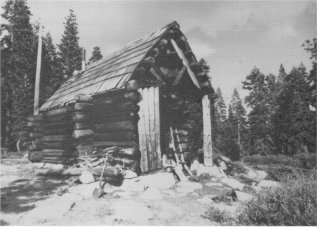

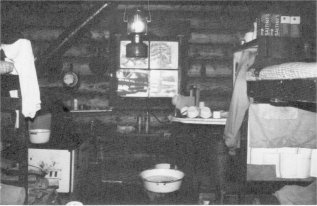

The CCC, however, remained the largest conservation movement in history. Yosemite’s CCC camps were among the first organized in the West, beginning operations on 6 June 1933. The park hosted several camps, at Crane Flat, Eleven-Mile Meadow, and Wawona, and later at Empire Meadow, Tamarack Flat, and The Cascades.5 The Park Service located its CCC camps near the work project areas, preferably near railroads or highways and water sources, and in close proximity to lumber and other building materials. The earliest camps consisted of army tents, which were gradually replaced by more substantial, but still temporary, wooden buildings. By 1934 the army had designed a prefabricated structure with interchangeable panels that could be easily erected and transported and could serve multiple purposes. The army mass produced these by 1935.

[5. “Camp Boys Build Trails and Help Improve Park,” Mariposa (Calif.) Gazette, Yosemite Valley edition, 81, no. 1: 12.]

Camps usually formed a U shape and contained recreation halls, a garage, a hospital, administrative buildings, a mess hall, officers’ quarters, enrollee barracks, and a schoolhouse. The space enclosed by the buildings served for group functions and sports. The wooden exteriors of the buildings were painted brown or green, creosoted, or covered with tar paper. In 1939, specific structures to be included in CCC camps consisted of barracks, a mess hall and kitchen, Technical Service quarters, officers’ quarters, a Technical Service Headquarters and storehouse combined, army headquarters and storehouse combined, a recreation building, a dispensary, a bathhouse, a latrine, garages, an oil house, a pump house, a generator house, a blacksmith shop, an educational building, and an equipment repair and maintenance building. Spike or stub tent camps sometimes sprang up separate from the main camp when a specific job too distant from the main for easy daily travel had to be completed or during fire hazard times so that the men could keep a close watch on forest conditions.6

[6. John C. Paige, The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History (Washington: National Park Service, 1985), 70-72, f n. 8; 73.]

The first work of CCC enrollees in Yosemite consisted of forest cleanup and improvement, roadside clearing, construction of horse trails, erection of telephone lines, construction of two egg-taking stations, development of public campgrounds, creek and river erosion control, sloping and planting of cut banks and road fills, insect control, and other forestry work such as removal of undesirable plants and revegetation.7

[7. Superintendent’s Monthly Reports, January-December 1933, microfilm rol #2, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center, 26-32.]

Emergency Conservation Work in the national parks and forests in general included the above work plus the construction and maintenance of fire breaks, campground clearing, trail clearing, construction of fire- and recreation-related structures, road and trail building, forest fire suppression, survey work, plant eradication, bridge building, flood control, tree disease control, and landscaping.8 Prior to ECW, forest fires had posed the gravest threat to the parks, but the Park Service had always lacked sufficient fire fighting personnel and had been unable to implement fire protection programs in each park. Civilian Conservation Corps personnel managed to reduce park fire losses tremendously beginning in the first nine months of 1933. The men not only located and suppressed fires, but constructed fire towers and telephone lines as well as roads, trails, and other firebreaks. The following year, refinements were made to park fire fighting programs and specific enrollees were selected for fire protection training. In general, each park’s fire protection plan became better implemented by use of ECW enrollees.9 All CCC work in natural areas of the National Park System was planned and overseen by landscape architects, park engineers, and foresters.10

[8. Paige, Civilian Conservation Corps, 18.]

[9. Ibid., 98-99.]

[10. Unrau and Williss, Expansion of the National Park Service, 81]

In 1935 the Park Service Branch of Forestry began publishing circulars on various aspects of fire fighting and forest conservation to guide ECW supervisors. Civilian Conservation Corps camps not only suppressed fires on Park Service lands, but began to cooperate in the protection of adjacent forests. In 1936 the Branch of Forestry requested ECW regional offices to send descriptions of each park’s fire fighting program to Washington to be reviewed and evaluated so that effective training programs could be developed. Yosemite ultimately gave fire suppression training to all enrollees but designated small groups as primary fire fighting teams. Fire protection training increased in 1937 and resulted in another sharp reduction in fire loss in the national parks. Fire fighting training increased in 1938 with fire fighting schools established nationwide.11 Although the Park Service continued to receive regular appropriations for fire protection and forest preservation during these years, they were insufficient and had to be supplemented by CCC funds.

[11. Paige, Civilian Conservation Corps, 99-101.]

The ECW/CCC also waged an intense battle against insects and disease. As early as 1932, Albright had requested emergency funding for a five-year program to combat pine beetles threatening timber stands in several of the western parks. Infestations of mountain pine and bark beetles were brought under control by the ECW in portions of Yosemite in 1933, after enrollees succeeded in destroying egg masses and cocoons of

|

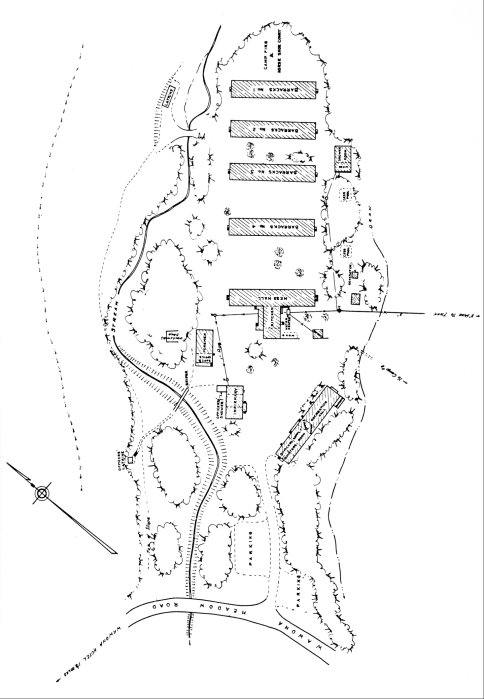

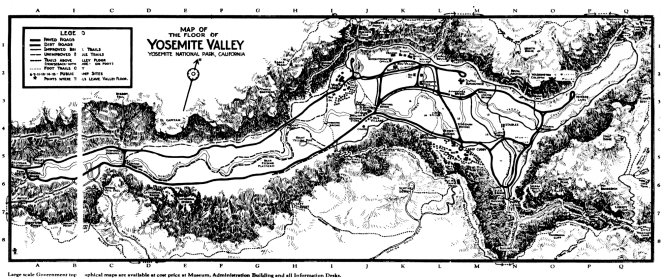

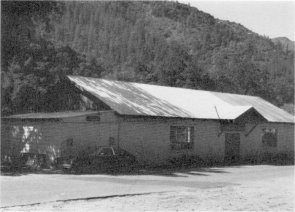

Illustration 135.

Map of CCC camp no. 1, Wawona, 1934. NPS, Denver Service Center files. |

[click to enlarge] |

[12. Ibid., 101-103.]

Because of some fears that the size and scope of ECW work and the make-work aspects of some of the other programs threatened the preservation policies of the Park Service and could result in damage to wildlife habitat, Director Albright placed certain restrictions on ECW activities. For instance, to prevent the removal of ground cover needed by wild animals, Albright insisted that underbrush and ground cover sufficient for small bird and mammal habitat be retained and clearing done only to the extent of removing serious fire hazards. The threat posed to park values by the introduction of exotic vegetation and artificial landscaping was assessed, with the result that a Department of the Interior manual on ECW work specified the use of native plants except in special cases. At Yosemite, then, revegetation consisted of sowing and transplanting native plant species along roadsides. Overdevelopment through new truck trails that provided access to primitive areas posed another danger. The Wildlife Division of the Park Service by the mid-1930s was feeling increased demand for scientific investigations and supervision of ECW projects involving conservation because of the perceived need to determine the impacts of those projects on wildlife and the natural environment. From the beginning of the ECW program until the end of 1935, an enlarged staff of biologists, foresters, geologists, and other specialists participated in making vegetation maps and conducting biological studies on birds, fish, and mammals at various parks, including Yosemite.13

[13. Ibid., 103-109.]

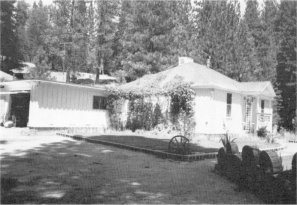

|

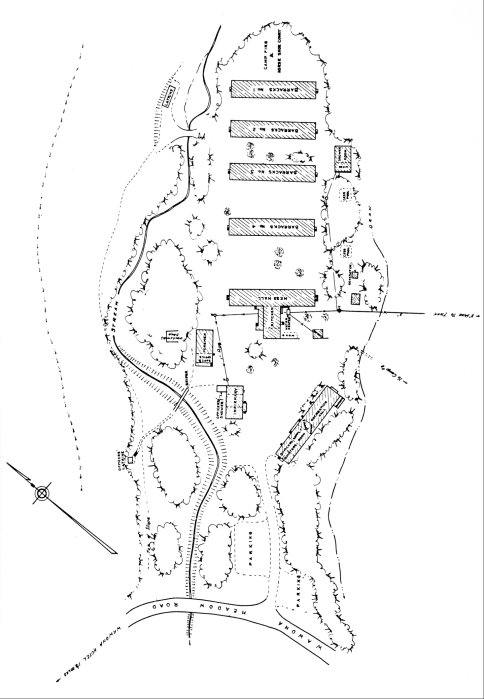

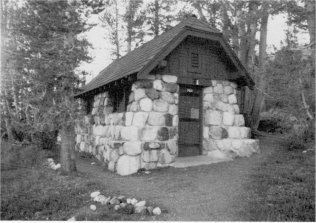

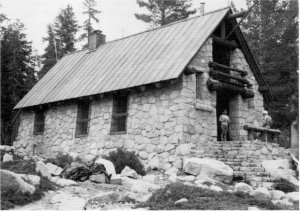

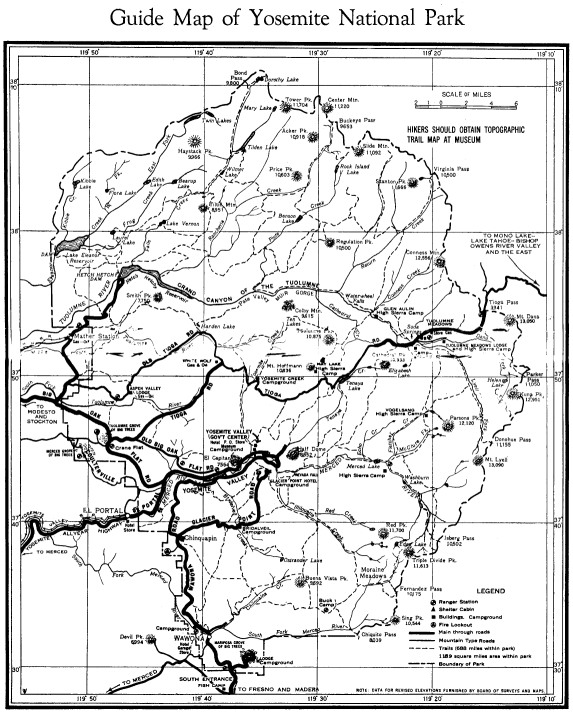

Illustration 136.

Map of CCC camp no. 2, Wawona, 1934. NPS, Denver Service Center files. |

[click to enlarge] |

Altogether, New Deal emergency projects increased the National Park Service budget by nearly $218,000,000, which underwrote most of the Park Service expansion and development projects of the 1930s. In sum, those programs, and the CCC in particular, improved the morale of America’s unemployed; provided education and practical job training to thousands of young men; enlarged the state parks system; advanced the national reforestation program; strengthened forest fire protection systems; advanced a nationwide erosion control and soil conservation program; assisted reclamation; increased recreational opportunities in forests and parks; promoted national interest in wildlife conservation by expanding fish hatcheries, improving streams and lakes, building rearing ponds, and restocking streams; aided grazing; and constructed thousands of bridges, service buildings, and other structures.14 It has been determined that the CCC advanced forestry and development in the national parks by at least ten to twenty years.

[14. Kieley, CCC, 44-46.]

The United States declared war on Japan on 8 December 1941 and on Germany and Italy on 11 December. Immediate mobilization and national defense preparations forced a reduction in CCC camps beginning in April 1941, which resulted in a reduction in the number of camps allocated to the Park Service. The termination of emergency programs was accompanied by a loss of park staff and CCC personnel, as enrollees began leaving for higher paying defense industry work or for military service, while their officers were being recalled for military duty. In addition, gas rationing cut park travel drastically. Park development maintenance, and repair fell to an all-time low as the Park Service terminated all CCC projects not directly related to the war effort. The final steps were then begun to reduce and eventually eliminate the CCC. The final decision to liquidate it was made on 30 June 1942 with enactment of the Labor-Federal Security Administration Appropriation Act for fiscal year 1943. During fiscal year 1942, camps were cut back, the CCC to be

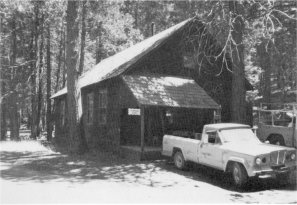

|

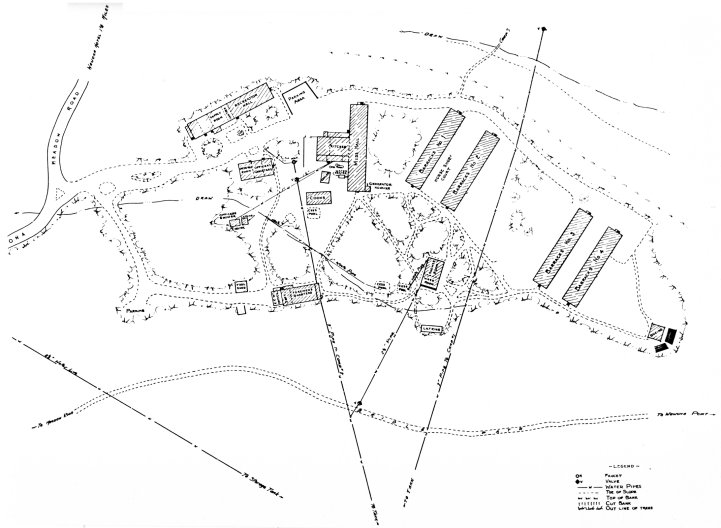

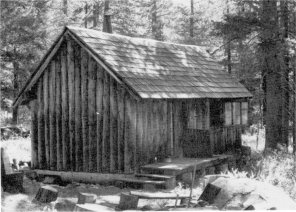

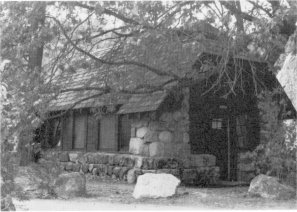

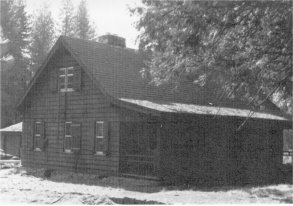

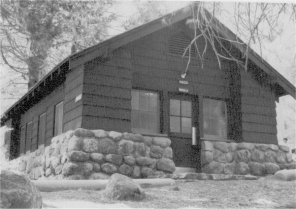

Illustration 137.

Sketch of Merced Grove CCC camp, 1935. Yosemite National Park Research Library and Records Center. |

[click to enlarge] |

[15. Wirth, Parks, Politics, and the People, 143-44.]

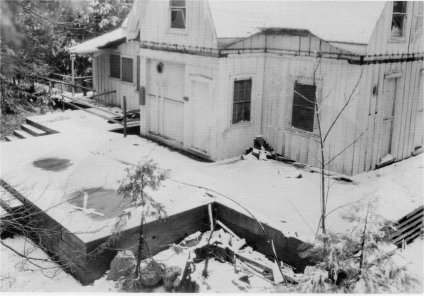

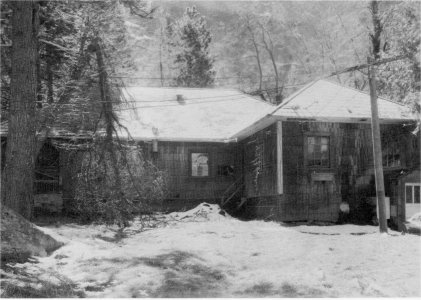

The act terminating the CCC stated that the War and Navy departments and the Civil Aeronautics Administration had first choice of CCC properties and materials. The various articles of office and construction equipment, autos, trucks, barracks furnishings, tools, and other items were to be inventoried and then transferred to the military for the war effort (i.e., as rest and relaxation camps or for conscientous objector work camps) or to the Park Service, other federal agencies, or state, county, or municipal agencies. Park Service policy dictated that CCC camp buildings either be used or torn down. After the war the Selective Service System transferred all former CCC properties it had received from the Park Service in the first months of World War II back to that agency for final disposition.16 Thus ended one of the great conservation programs in American history. The work projects of the New Deal had not only protected and conserved the country’s exceptional natural resources but had developed national and state park and recreational areas for the public benefit.

[16. Paige, Civilian Conservation Corps, 36-37. Following discontinuance of the CCC program in 1942, the Wawona CCC buildings were held for use as a possible public service camp. During the latter part of April 1943, authority was granted the army for the occupation of the former Wawona CCC camp by several hundred men of the 426th Signal Battalion, Camp Pinedale, California, for special training. During December 1943, negotiations were completed for the transfer of the former Wawona CCC camp to the Western Signal Aviation Unit Training Center, Camp Pinedale, and the army stationed a small unit at the camp to protect its property. U. S. Army Signal Corps units utilized Park Service facilities both at Wawona and Badger Pass as special summer training schools. Even prior to America’s formal entry into World War II, mechanized army units had conducted maneuvers in the park to break in new equipment and gain experience in motor convoys. They stayed in campgrounds 14 and 15. “U. S. Soldiers in Yosemite for Practice,” Mariposa (Calif.) Gazette, May 1940.]

Former Director Conrad Wirth stated:

development by many years. It made possible the development of many protective facilities on the areas that comprise the National Park System, and also provided, for the first time, a Federal aid program for State park systems through which the National Park Service gave technical assistance and administrative guidance for immediate park developments and long-range planning. . . .

The Civilian Conservation Corps advanced park The National Park System benefited immeasurably by the Civilian Conservation Corps, principally through the building of many greatly needed fire trails and other forest fire-preventional facilities such as lookout towers and ranger cabins. During the life of the CCC, the areas received the best fire protection in the history of the Service. . . . The CCC also provided the manpower and materials to construct many administrative and public-use facilities such as utility buildings, sanitation and water systems, housing for its employees, service roads, campground improvement, and museums and exhibits; to do reforestation and work relating to insect and disease control; to improve the roadsides; to restore historic sites and buildings; to perform erosion control, and sand fixation research and work; to make various travel and use studies; and to do many other developmental and administrative tasks that are so important to the proper protection and use of the National Park System.

The CCC made available to the superintendents of the national parks, for the first time, a certain amount of manpower that allowed them to do many important jobs when and as they arose. Many of these jobs made the difference between a well-managed park and one “just getting along.”

3. The Dissolution of Emergency Relief Projects Severely Impacts Park Conditions

The tremendous progress of the 1930s relative to national park construction, protection, and conservation, however, virtually stopped cold in the next decade as the United States became actively involved in World War II. Yearly Park Service appropriations dropped from thirty-five million dollars in 1940 to less than five million dollars in 1945. The impact on the parks was drastic, as facilities deteriorated, visitation slowed to a trickle, and other government agencies and private industry

[17. Wirth, Parks, Politics, and the People, 147-48.]

attempted to use the excuse of a national emergency as a means of appropriating park resources. A steadfast leader was needed to oppose that onslaught and protect the ideals that had been furthered by the New Deal emergency programs.Horace Albright had left the Park Service in early 1933 to become vice president and general manager of the U. S. Potash Company. Arno B. Cammerer, associate director under Albright, replaced him as director and Arthur E. Demaray become associate director. Both Cammerer and Demaray had worked under Mather. Harold L. Ickes had served as Secretary of the Interior during the boom period of the 1930s and oversaw the expansion of park and recreational activities. In 1940 the overworked Cammerer asked to be relieved of his duties, and Ickes replaced him with Newton B. Drury, a highly respected conservationist. Drury stood firm against all threats to park resources during the war years while also trying to deal with the economic and developmental crisis brought on by the termination of the emergency relief projects. Despite the fact that its roads and structures were being heavily damaged by lack of maintenance, the Park Service made important contributions to the war effort. It cooperated to the fullest extent with the military and with federal agencies involved in war activities without allowing its resources to completely deteriorate. It made many of its facilities, especially concession-owned ones, available to the military as rest areas for injured men. Some parks provided areas for mountain maneuvers and the training of ski tropps. At the same time Park Service officials managed to fend off encroachments by mining and lumber interests.

Park visitation began to increase rapidly as the United States demobilized after the war, due to increased leisure time, more prosperity, and improved transportation. By the 1950s, however, the lack of maintenance in the parks had caused such deterioration of roads, buildings, and other facilities that they were completely inadequate and desperately in need of replacement. Although the Park Service budget picked up after V-E day, grants-in-aid to other countries during the Cold War repositioning period of international compacts and defense agreements seriously limited the money available to the Park Service to rebuild and refurbish park facilities. Park visitation, on the other hand, started to increase. In 1951 Drury accepted the job of head of the State Parks of California. Demaray, who had continued as associate director, accepted the Park Service directorship for a year, the last “Mather man” to hold that position. In December 1951 Conrad L. Wirth replaced him, serving as director until January 1964.

By 1955 the parks situation had become drastic. Park visitation had increased threefold since 1940. Eighteen new areas had been added to the system, increasing its holdings by several million acres. In Yosemite both Park Service structures and concession facilities were in need of extensive renovation. Increasing numbers of park visitors were not only causing overuse of resources, but were experiencing less enjoyable stays. Something had to be done to awaken Congress and the public to the impending loss of important natural and historical resources. Only a large sum of money could repair the damage to the parks caused by a minimum budget over the last several years. Above all, Wirth refused to give in to pressures to close some of the parks, preferring instead to attempt to rebuild the entire park system.

4. MISSION 66 Revives Park Development

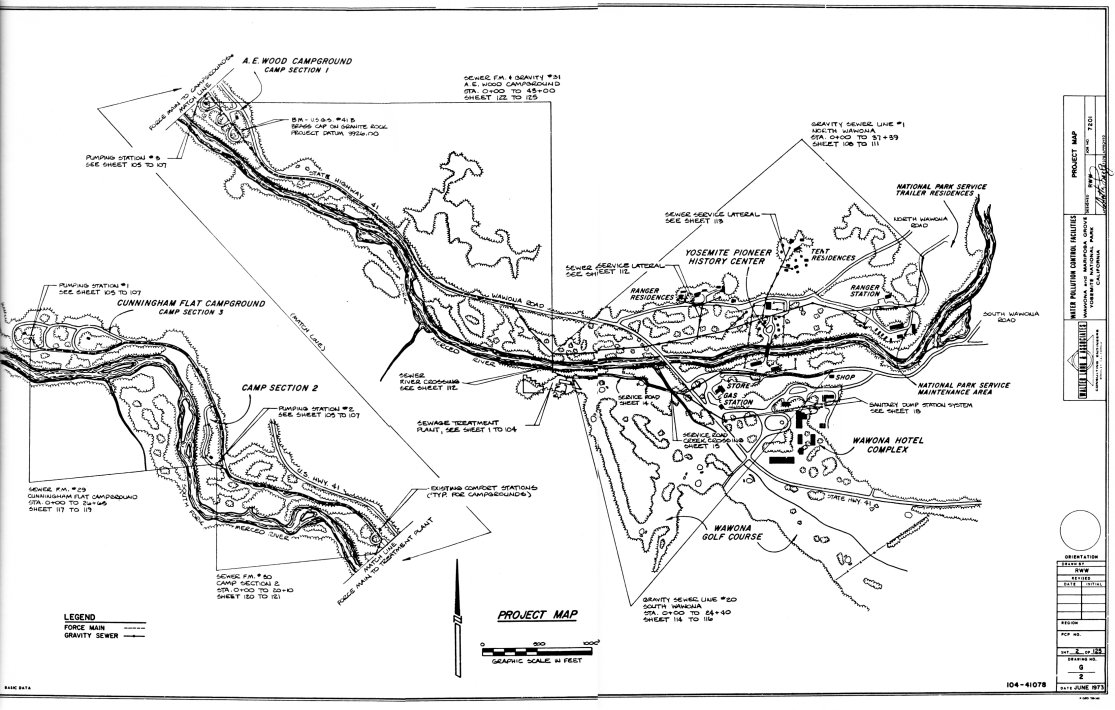

Wirth’s solution to the problem lay in MISSION 66, conceived of in 1956 as a comprehensive ten-year program to upgrade and expand national park facilities to accommodate anticipated visitor use by 1966, the fiftieth anniversery of the National Park Service. In addition to construction of needed housing and other service structures and provision of essential services, such as sanitation facilities and water, sewer, and electrical systems, the program aimed at providing adequate operating funds and field staffs and acquiring private lands for protection and/or use.18 Master plans again became important in drawing up the MISSION 66 program, for many of them contained projects that needed financing and MISSION 66 provided the momentum for their accomplishment. Many projects were completed that improved the protection and preservation of park values. Many involved major road construction that was handled by the Bureau of Public Roads working with Park Service landscape architects. Since the mid-1920s, U. S. Public Health Service sanitary engineers had worked with the design office and the parks to improve sanitary facilities.19

[18. Shankland, Steve Mather, 326-27. Development under this program was to proceed with paramount consideration being protecting park areas for the purpose for which they had been established. Another function of MISSION 66 was to determine what was needed to round out the National Park System.]

[19. As stated earlier, master plans had been prepared for each Park Service area in the 1930s, by resident landscape architects of the San Francisco planning office that were assigned to major parks or groups of parks. This Central Design and Construction Division headed by Tom Vint later dispersed to regional offices in 1936. In 1954 Vint’s planning staff was reorganized into Western and Eastern Design and Construction offices in San Francisco and Philadelphia. Although they continued to primarily prepare and update master plans, during MISSION 66 they also designed and supervised construction projects. These master plans ensured the preservation of natural features and the placing of necessary facilities on sites where they blended into the landscape as much as possible. Wirth, Parks, Politics, and the People, 60-62.]

Construction became an important element of the MISSION 66 program, involving replacing outdated, inadequate facilities with improvements designed to handle increased loads but to be located in such areas as to reduce impact on the environment. At Yosemite, MISSION 66 proposed to provide an adequate road and trail system, sufficient accommodations and facilities for visitors, and effective interpretation of the resources. Another necessary part of the program included facilities and personnel necessary for the administration, maintenance, and protection of the park and housing for them. MISSION 66 planning incorporated many of the thoughts of the Yosemite Advisory Board regarding resolution of Yosemite’s manmade problems.

The park undertook its development program with the intent of not diminishing existing wilderness areas by extending roads or other development beyond their defined limits at that time and vowed that developments thought to be necessary for wilderness use would be appropriate to that environment. In addition, visitor accommodations and related services would be limited to designated areas. Specific items of Yosemite’s MISSION 66 program included:

1. Protection of Yosemite Valley. The Park Service realized that:The limited area of the Valley, in relation to the physical facilities essential to operate the park and to serve the tremendous number of park visitors attracted to it, is the heart of the problem. We can no longer continue to build, construct and develop operating facilities on the Valley floor without seriously impairing and ultimately destroying those very qualities and values which the National Park Service was created to preserve and protect for future generations. The more space taken up on the Valley floor for repair and maintenance shops, warehouses, incinerators, employee housing, equipment storage and other operating facilities means thatp^much less space available for visitor use and enjoyment.20

Specifically park authorities intended to limit valley facilities to those necessary to directly serve the visitor, with supporting facilities for parkwide operation located elsewhere, probably in El Portal. This would include removing the obsolete incinerator and public dump and replacing them at the new operating base.

[20. National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, MISSION 66 for Yosemite National Park, n.d. (ca. 1956), in Box 22, Backcountry, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center, 4.]

2. Completion of the road and trail system, primarily the Crane Flat and Tioga Road entrance routes. The influx of travel to the park primarily via the South and Arch Rock entrances had resulted in an imbalance in park development and an unequal distribution of visitor load. Several important trail connections needed completion and repair of trails closed due to lack of maintenance was required. Completion of this system would allow visitor-use development in other portions of the park and relieve the pressure on concession facilities and the congestion in Yosemite Valley.

3. Construction of new water and sewer systems for government and concession developments to conform to U. S. Public Health Service requirements and of visitor-use facilities.

4. Replacement of obsolete concession facilities in Yosemite Valley, improvement of others parkwide, and provision of additional accommodations in other areas to relieve overcrowding. Although the park’s concessioners had been willing before to undertake this additional investment, prior to MISSION 66 the Park Service had been unable to provide the prerequisite access roads, parking areas, and utilities.

5. Acquisition of private lands. At this time the remaining private lands were located in the few remaining park areas whose level character and adequate water resources made them possible sites for public-use development. The land acquisition program would be time-consuming and laborious because the larger tracts had been subdivided into smaller lots. Again it was stressed that privately owned lands conflicted with public enjoyment and that maximum public use dictated their acquisition.21

[21. See ibid, for a description of the MISSION 66 program in Yosemite National Park, including summaries of the problems, program, and cost.]

The MISSION 66 program gained immediate acceptance from the President, Congress, and the American public. Park Service appropriations began to flow and even increase. Construction accomplishments of the period included park roads, trails, parking areas, campgrounds, picnic areas, campfire circles and amphitheaters, utilities, administrative and service buildings, utility buildings, reconstruction and rehabilitation of historic buildings, construction of employee residences, dormitories, apartments, comfort stations, interpretive roadside and trailside exhibits, lookout towers, and entrance stations. Other important innovations included visitor centers to house interpretive programs and ranger training centers. The Stephen T. Mather Research and Interpretive Ranger School at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, for ranger historians and naturalists, was an outgrowth of the Yosemite Field School of Natural History. The Horace M. Albright Ranger School at Grand Canyon served the ranger protective force.22

[22. Shankland, Steve Mather, 329.]

Concessioners invested a great deal of their money in new cabins, lodges, stores, shops, service stations, and the like. MISSION 66 also took steps to move administrative facilities, government housing, utility buildings, and shops out of national parks to reduce interference with park enjoyment. In this regard, a new employee residential and service area was established at El Portal. At the same time, because MISSION 66 in Yosemite Valley called for moving all development out of the valley meadows, the concessioner moved all his operations to the side of the valley, helping in meadow naturalization and improving scenic values. Concessioners were recognized as an important part of the MISSION 66 program. Also during MISSION 66, the Park Service removed itself from the power and communications utility business, switching over to commercial service on a contract basis.

The MISSION 66 program was early criticized as being overly road- and development-oriented, with little accomplished in terms lines of natural resource protection. In Yosemite, especially, the program continued Mather’s thrust of more accommodations and facilities, increased access to remote areas, and expansion of interpretive programs and facilities. Even at this point, the Park Service was not grasping the critical nature of the imbalance being created between visitor use and preservation of the natural environment. Those aspects of the MISSION 66 program in Yosemite that concerned limiting developments within the valley to facilities necessary to directly serve the visitor, with supporting facilities located elsewhere, are still under study and implementation. The program did, however, succeed in supplying more adequate facilities and services to enable the Yosemite visitor to better use and enjoy the park. In ensuing years questions of overuse, noise, congestion, vandalism, crime, wilderness impact, commercialization, concession policy, and wildlife management, and development plans that included new valley accommodations, an aerial tramway, and a new winter sports area, would complicate further master planning efforts of the 1970s and 1980s. The conflicting demands of use and preservation imposed on the national parks by today’s urban-oriented society, accustomed to certain amenities and privileges, will not be easily resolved.

Beginning in the 1930s and amid renewed efforts to promote the parks and preservation in general, access to Yosemite’s backcountry became important in terms of expanding visitor enjoyment and use of the park. Consideration of it as an entity with its own set of administrative problems and environmental concerns was not yet a primary issue. New trails, in addition to the High Sierra camps and park patrol cabins, promoted more intensive backcountry visitation. Although plans were voiced for new trails to open up new vistas and areas of special interest, the economic stringencies of the Depression and World War II killed such proposals. Inroads on the wilderness did not appear again with any intensity until the 1950s, at which time principles of resource management began to influence the park’s view and subsequent use of that area. The backcountry’s operations have remained of secondary importance to those of Yosemite Valley throughout most of the park’s history, with little formal coordination of studies or development. The park did not establish a Backcountry Office until 1972, which attempted to coordinate activities of the ranger, maintenance, and research staffs and to fit them into broader environmental programs. Establishment of this office finally acknowledged the importance of lesser-used sections of the park and their resources.

Meanwhile, advocacy for the “wilderness” park experience gained momentum as park visitors began to realize the enjoyment of hiking and backpacking in the backcountry. More sophisticated camping gear and a deeper appreciation of the environment no doubt contributed to the popularity of this type of experience. It remained harmonious with the initial concept of national parks as a place of refuge and contemplation but involved very different types of activities and land use than those expounded by Mather’s generation. In place of camps and roads, wilderness enthusiasts called for no artificial conveniences or motorized access routes. The Wilderness Act of 1964 meant that some control could be exerted on undeveloped backcountry in our national parks, especially in the West. In Yosemite the move toward “wilderness” resulted, among other things, in discontinuance of the firefall in 1968 as inconsistent with national park values. The California Wilderness Act of 1984, restricting backcountry use and development, finally placed wilderness concerns on a more equal footing with other park operations and ensured that planning and management objectives would consider the overdevelopment and abuse of resources in Yosemite Valley and would prevent that from occurring on a parkwide basis as much as possible.23

[23. See Snyder, “Yosemite Wilderness—An Overview,” 3-4.]

1. Trail Construction in the Early 1930s Results in Completion of John Muir Trail

By the early 1930s Yosemite’s trail network was largely complete, and trail crews began concentrating more on maintenance than construction. Some new work continued to be accomplished, however. In 1931 park crews completed the trail from Happy Isles to Merced Lake, including a new section between Little Yosemite and Lost valleys, considered one of the finest examples of modern trail construction in the national parks. (This stretch should be inspected and evaluated during the backcountry trail survey recommended later in this report.) In addition to constructing a parapet wall on the Vernal-Nevada falls trail above Happy Isles, workers installed a counting device near the foot of the trail containing a photo-electric cell. The device proved only moderately successful because it counted people twice who returned to investigate the curious apparatus. Crews also constructed three new footbridges at Happy Isles. Backcountry trail work included construction of the Chilnualna Trail; of the Isberg Pass trail, including a bridge across the Lyell Fork of the Merced; and of a trail from May Lake to Ten Lakes.

The city of San Francisco constructed more than twenty-four miles of trail during 1930-31 at a cost of about eighty-six thousand dollars. The work included trails with a width of six feet and a maximum grade of about sixteen percent and five trail bridges, most of which the December 1937 flood destroyed.24 Trail construction by the city in 1931 involved the Rancheria Trail, a bridge across Rancheria Creek, the Falls Creek Bridge at the mouth of Lake Vernon, and the Lake Vernon trail. Also in 1931 workers completed the John Muir Trail section on the north side of Foresta Pass and opened several miles of new trail south to Tyndall Creek. Fifty-thousand dollars of state funds had been used on construction of the trail, which stood complete except for a section up Palisade Creek. Other trail work in 1932 consisted of replacing the Half Dome cables and log bridges at Yosemite Fall and in the Lost Arrow section. Finally, in 1938 U. S. Forest Service crews working on the Muir Trail built steep switchbacks (the Golden Staircase) up the cliff below Palisade Lakes and across to Mather Pass and the headwaters of the South Fork of the Kings River. Fifty-four years of difficult construction had resulted in the fulfillment of Theodore Solomons’s dream.

[24. Memo to the Superintendent, Yosemite National Park, from E. M. Hilton, Park Engineer, 30 September 1941, in Box 83, Trails—1941 to 1942, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

|

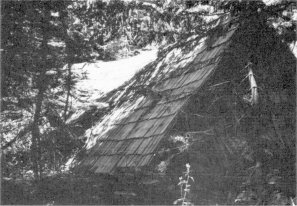

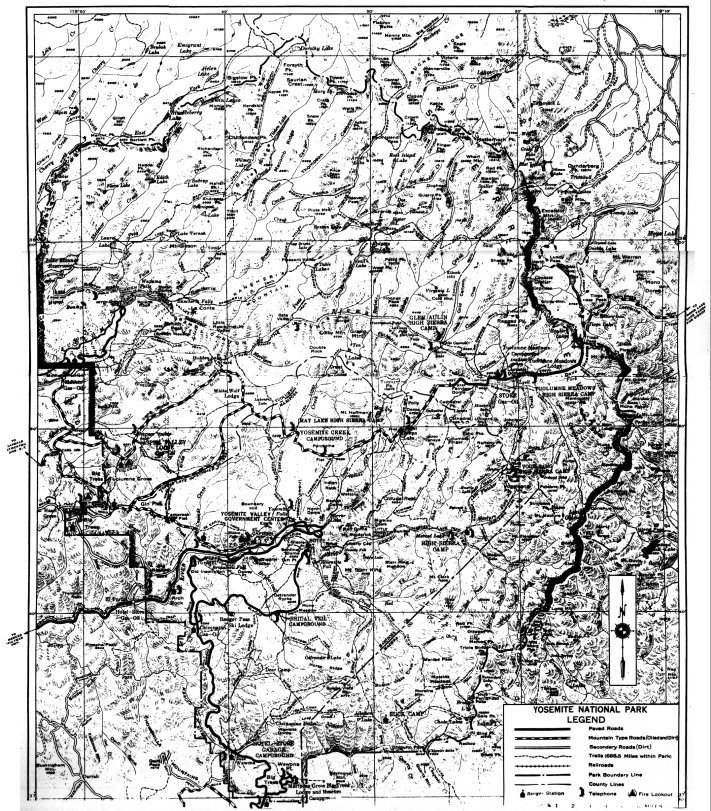

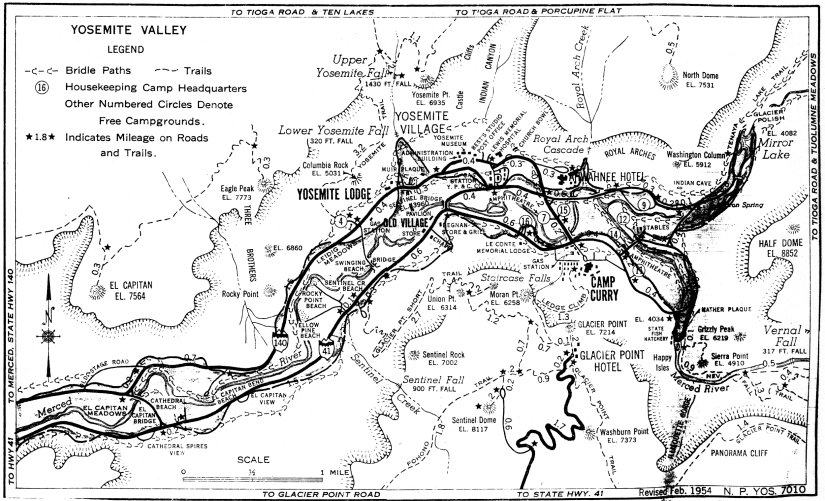

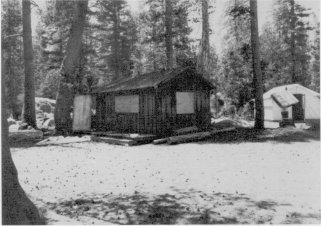

Illustration 138.

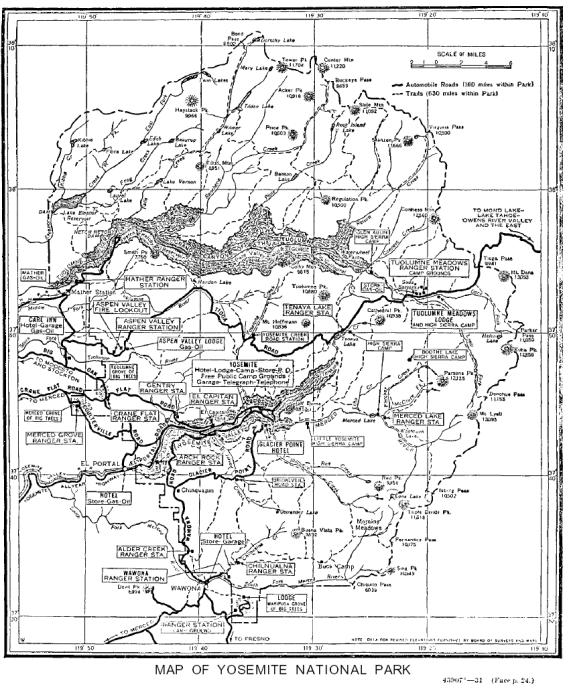

Map of Yosemite National Park. From Circular of General Information Regarding Yosemite National Park, California, USDI, 1931. |

[click to enlarge] |

2. Reconstruction of Park Roads Begins in Early 1930s

a) Paving and Tunnel and Bridge Building Commence

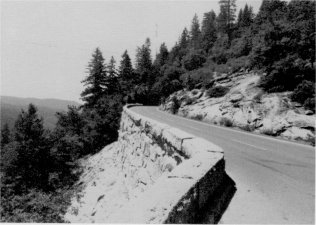

One of the major construction projects underway at this time involved driving of the new Wawona Road tunnel. By 1931 the two and a half million-dollar reconstruction program for the Wawona Road had begun, and crews had already vastly improved the stretch of highway from Wawona to Alder Creek. From that point to the valley, travelers still used the old road because of ongoing tunnel construction. Other road work in 1931 included paving by the city of San Francisco of the highway from Mather Station to Hetch Hetchy Valley, removal of the El Capitan Bridge in Yosemite Valley, and completion of a three-span, steel, I-beam bridge supported by cement rubble-masonry abutments and piers, over the South Fork of the Merced at Wawona.25

[25. Superintendents’s Monthly Reports, January-December 1931, microfile roll #2, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

The new El Portal road, meanwhile, was carrying a heavy load of traffic into the park both in the summer and winter. In 1932 forty-six turnouts were constructed along the road, and stretches of dry-laid rock retaining walls added to those already existing with attention paid to landscape values.26

[26. “Completion Report. Final Report: Account No. 501.37, El Portal Road Shoulders and Turnouts,” November 1932, in Maintenance Office, Yosemite National Park.]

b) Tioga Road

The mpost important missing link in the park’s road system remained the twenty-one-mile section of Tioga Road which had not been improved for auto travel since its construction in the 1880s. As the only route available for those wishing to enter the park from the east, its rehabilitation had high priority. As mentioned, the Raker Act, turning the Hetch Hetchy Valley over to the city of San Francisco, had provided that the city build certain roads, including one from Crane Flat to Mather and another from Mather to White Wolf to replace the existing Tioga Road section between those points. Under a later modification of the act, the city agreed to turn over to the Park Service one and a quarter million dollars in lieu of constructing those roads, the money to be used for construction of a new Tioga Road on any desired route. Reconstruction of the road began in the early 1930s with PWA funds. Close attention was paid to location of the roadbed and placement of alignments, grades, cuts, fills, and structures such as bridges, culverts, and parking areas to ensure harmony with the landscape. The project was continually reviewed and assessed by such groups as the Yosemite Advisory Board and the Sierra Club.27 The park decided to preserve portions of the old road for continued use as an alternate route and as access to primitive campgrounds that would then be opened in that portion of the park.

[27. Wirth, Parks, Politics, and the People, 358-59.]

Surveys of the new route began in 1931, with construction of the Tuolumne Meadows section from Cathedral Creek to Tioga Pass reaching completion in 1934. Surfacing of that section began in 1935 and ended in 1937. During 1938 oiling of the twenty-one-mile section of the old road from McSwain Meadows to Cathedral Creek took place, and with completion of fourteen and one-half miles of new road between Crane Flat and McSwain Meadows on July 1939, a new era began. It would be almost twenty-five years before workers replaced the twenty-one-mile central section of the old road, but at least now a fair portion of the road was dustless. Crews also constructed a single-span, steel, I-beam bridge on masonry abutments over the South Fork of the Tuolumne River in October 1937 in connection with this work.

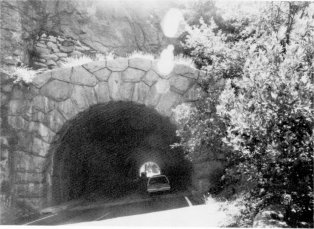

c) Wawona Road and Tunnel

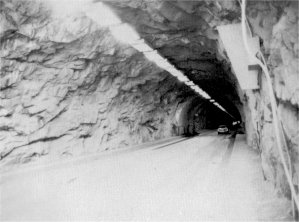

Work on the Wawona tunnel on the new Wawona Road ended in 1932. The new highway eliminated the steep grades, sharp curves, and switchbacks of the old road and the tunnel prevented defacing of the

|

Illustration 139.

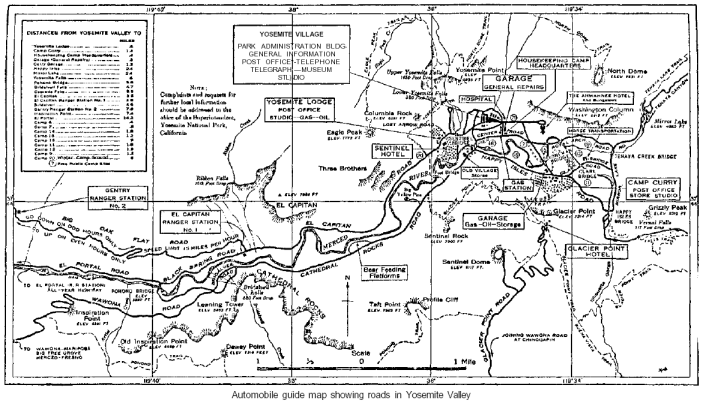

Automobile guide map showing roads in Yosemite Valley. From Circular of General Information Regarding Yosemite National Park, California, USDI, 1931. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 140.

Stone steps on Mist Trail. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 141.

Happy Isles Bridge. Photos by Linda W. Greene, 1985. |

[click to enlarge] |

Because there were no galleries such as those in the auto tunnel at Zion National Park in Utah, three shafts drilled from the tunnel horizontally to the cliff face provided necessary ventilation. Carbon-monoxide recorders controlled three large fans in the largest adit. The recorders would register a buildup of traffic in the tunnel, with its subsequent increase in exhaust gases, and additional power would automatically be applied to the fans and continue as long as needed. The longest motor vehicle tunnel in the western United States at the time, it was considered a bold piece of engineering work that also managed to preserve the cliff walls and other landscape values. Construction on the section of the Wawona Road that included the tunnel had begun in November 1930, and the stretch opened to traffic in the spring of 1933.

With completion of the Wawona Road, interested parties began applying pressure to make the high country of the Tuolumne River more accessible for winter sports by constructing a tunnel road up through Tenaya Canyon. Herbert C. Hoover, on vacation in Yosemite before becoming President, had ridden horseback from the High Sierra camp at Tenaya Lake down the Snow Creek switchbacks into Yosemite Valley. Impressed with the scenery, he had suggested installing automatic elevators working by electrical power, possibly developed from waterwheels, that would take autos up and down alongside Snow Creek Falls.28 Hoover thought it would prove a great tourist attraction!

[28. Harry Chandler to C. G. Thomson, 10 August 1932, Central Files, RG 79, NA.]

Other road work in that year included rerouting of the road by the Grizzly Giant Tree in the Mariposa Grove in the spring of 1932 because the old road stood so close to the tree that vehicles ran over some of its roots. Gabriel Sovulewski also in that year made a spur road from Crane Flat to the Merced Grove by connecting the old Davis Cut-off with the railroad grade of the Yosemite Lumber Company that stretched from Camp 16 to Camp 15. During 1933-34 the Mariposa Grove’s road system was paved with asphalt.

d) Yosemite Valley Bridges

During 1933 the park accomplished some major bridge work in Yosemite Valley. In addition to completing a steel girder bridge on masonry abutments over Bridalveil Creek, workers finished replacing the Stoneman Bridge across the Merced River at the Camp Curry intersection. Another reinforced-concrete, arched structure veneered with native granite, it also featured two equestrian subways through its abutments. When it came to replacing the El Capitan Bridge over the Merced, connecting the North and South roads, Superintendent C. G. Thomson expressed his opposition to another arch bridge for that location. He believed the park had repeated the stone arch motif to the point of monotony and that this bridge’s location several miles from the group of stone-arch bridges permitted some flexibility in design. The new three-span bridge, therefore, had steel I-beams with a log veneer railing. Workers placed it about one mile upstream from the old bridge location.

e) Glacier Point Road

During this time the park began to study the most desirable road route from Chinquapin to Glacier Point. The existing narrow road, poorly aligned and plagued by steep grades, had by now become obsolete. The major proposals for rehabilitation consisted of widening the road, eliminating the most objectionable switchbacks, and creating parking areas at the end of the road and at Washburn Point.29

[29. Superintendent’s Monthly Reports, January-December 1933, microfilm roll #2, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

In 1934 park CCC crews installed posts and replaced the old 3/8-inch Half Dome cable with a 7/8-inch one and also constructed a log footbridge for fishermen across the Merced River at Arch Rock, a small bridge across Crane Creek on the Coulterville Road, and a new concrete two-span road bridge across the Tuolumne River at Tuolumne Meadows. Road construction consisted of rerouting the Mariposa Grove road behind the museum and adding a parking area, and work on the new Glacier Point Road. The latter closely followed the old road from Glacier Point to near Bridalveil Creek. At that point the new route left the steep hills and followed wide, easy curves on a gentle grade around them. The park completed the road in October 1935 and Superintendent Thomson wrote the Park Service director:

It is difficiult to realize that the much-talked-of Glacier Point Road is now an actuality. You will recall the long studies and discussions of the feasibility of any modern road, the substitution of a tramway for the road, the loop road proposal, and the proposals to stop at Sentinel Saddle or at Washburn Point. This Glacier Point subject was precipitated practically upon my arrival here nearly 7 years ago, and into the picture we drew Mr. Albright, all of the Advisory Board, Dr. Hewes, Mr. Tolen, Mr. Roach, Dr. Matthes, Dr. Tresidder, Mr. Wosky, and at least a score of others with lesser interests. Riding over it today, I could not but recall the dozens of meetings, discussions, and the endless miles some of us have hiked in search of solutions. . . . So far as Yosemite is concerned, it easily marks the highest standard yet attained in road construction through difficult country.30

[30. C. G. Thomson to Director, National Park Service, 15 October 1935, in File 631-10, Glacier Point Road, 1934 to 1950, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

f) Big Oak Flat Road

In 1935 the park completed the Bridalveil Fall parking area and started work on the new Big Oak Flat Road out of Yosemite Valley. The planned route left the All-Year Highway a short distance below the floor of the valley, near the powerhouse diversion dam, and climbed the north wall of the Merced River canyon just above The Cascades. In the four miles to Meyer Pass, where the road would cross the rim of the canyon, two short tunnels and one long one would avoid defacement of the outstanding granite cliffs. Much of the work would be done by day labor under the close supervision of landscape engineers to safeguard the natural appearance of this stretch. Long sections of rock wall would hide unsightly scars from any deep cuts that would be necessary.

g) Trail and Road Signs

As stated previously, a trail measuring and signing program in the mid-1920s had involved running an odometer mounted on a bicycle wheel behind a horse and nailing small, round tin tags with numbers and letters to trees to identify trails. Later signs were of enameled metal with white backgrounds and green lettering. In 1934-35 the park began resigning park trails with locally manufactured embossed aluminum signs done on a Roover Press. In preparation for that work, rangers began securing accurate mileages and compiling a trail map. A common practice throughout the park by the 1940s involved painting large orange arrows on open granite expanses crossed by trails to direct hikers. Auto license plates, painted yellow and nailed ten to fifteen feet high on trees, helped designate trails to snow gaugers during winter storm conditions. Another sign type in the war years involved routing white-painted letters on 1-1/2-inch-thick redwood planks about four feet above the trail, but these also fell prey to bears, perhaps attracted to the oil used, as well as to hikers for campfires, souvenirs, or simply as

|

Illustration 142.

Wawona tunnel, east portal. Photo by Robert C. Pavlik, 1985. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

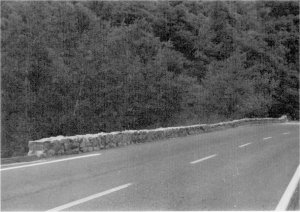

Illustration 144.

Stone wall on State Highway 140. Photo by Robert C. Pavlik, 1984. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 143.

Wawona tunnel, interior. Photo by Paul Cloyd, 1986. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 145.

Map of Yosemite Valley floor, ca. 1935. NPS, Western Regional Office files. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

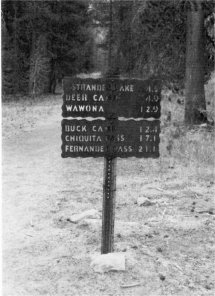

Illustration 146.

Metal trail sign. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

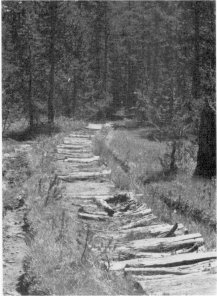

Illustration 147.

Corduroy road along north side of Johnson Lake enroute to Crescent Lake. Photos by Robert C. Pavlik, 1984-85. |

[click to enlarge] |

[31. Bert Sault to Jim Snyder, 9 July 1975, in Separates File, Yosemite-Trails, Y-46, #42, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center. Evidently Landscape Architect Thomas Vint was not favorably impressed with the new iron signs for aesthetic reasons, but agreed that they were necessary to solve the problem of signage in the backcountry. Notes taken by Carl P. Russell, “Conference July 30, 1952,” in Box 78, Box A—NPS files, 1938-1953, Development Part XII, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center. The metal sign program in Yosemite was initiated with designs by signmaker Lee Buzzini and welder Bill Kirk. Douglas H. Hubbard, “Yosemite Bears Chip Teeth,” Yosemite Nature Notes 34, no. 3 (March 1955).]

h) Bridge Work Precedes Flood of 1937

In July 1936 construction took place on the May Lake trail from the top of the Tenaya zigzags to the junction of the McGee Lake Trail. In 1937 workers built a new hikers’ bridge across Tenaya Creek below Mirror Lake. That same year, the park completed plans for a log footbridge at Wawona, crossing the South Fork close to the new Wawona schoolhouse, to provide access for children living on the south side of the river in Section 35 so that they would not have to use the longer route to school over the old covered bridge downstream.32

[32. Superintendent’s Monthly Reports, January-December 1936 and 1937, microfilm roll #3, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

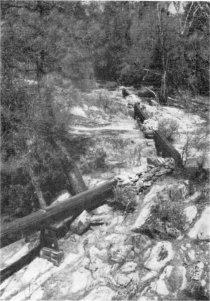

A disaster of unparalleled proportions in park history hit the area on 8 December 1937 when torrential rains continuing until 12 December caused severe flooding in the valley and washouts in other sections of the park. Particular devastation occurred in Yosemite Valley where the formation of an immense lake resulted in damage to road surfaces, businesses, and residences, and inundation of campgrounds 6 and 16. The force of the floodwaters surging down the Merced River canyon practically destroyed the diversion dam, intake, and penstock of the powerhouse, and severely damaged bridges at The Cascades, the footbridge and structures at the Arch Rock entrance and at the Cascades CCC camp, and portions of the El Portal road where sections of the stone guard rail and road slab slid into the river. Repairs began immediately, and the El Portal road, initially closed completely for the rest of December, remained one-way passage during the reconstruction period. Extensive sections of retaining and parapet walls were replaced and added with great effort.

The Mirror Lake road sustained heavy damage from Iron Spring to the parking area. Floodwaters washed away seventeen trail bridges on the valley floor, with the El Capitan Bridge sustaining heavy damage. Sections of the Wawona Road also were damaged. The new footbridge across the South Fork of the Merced to the new schoolhouse was completely wrecked by the flood.33

[33. “Monthly Narrative Report to Chief Architect by E. L. McKown, Resident Landscape Architect, November 25 to December 25, 1937, Region IV, Yosemite National Park, California,” 23 December 1937, Architectural Reports (1927-1939), in Box 28, Yosemite Park and Curry Company, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center, 1-3, 5.]

The flood damage of December 1937 necessitated a multitude of repairs during 1938-39, including replacement of bridges near Yosemite Lodge, on the lower Yosemite Fall trail and at Rancheria Creek near Hetch Hetchy, and of the East Bridge at The Cascades on the Ail-Year Highway, and of the Coulterville and Davis Cut-off bridges across Crane Creek; of footbridges at Happy Isles, Yosemite Creek, Camps 7-16, Mirror Lake, and on the South Fork; and of horse bridges over the Merced River, Bridalveil Creek, Tiltill Creek, Snow Creek, Eagle Creek, Yosemite Creek, Tenaya Creek, and Mono Creek, and at Pate Valley and Glen Aulin. Repair work continued on the All-Year Highway at Devil’s Elbow, one mile below Arch Rock, in addition to repair of pavement, replacement of parapet walls, and removal of silt, mud, and assorted debris on valley roads.

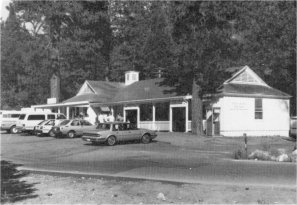

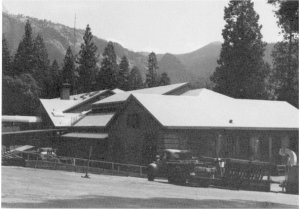

|

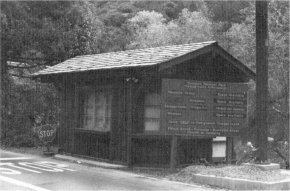

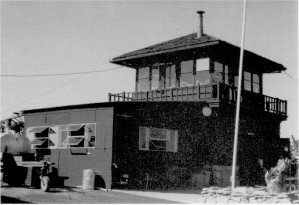

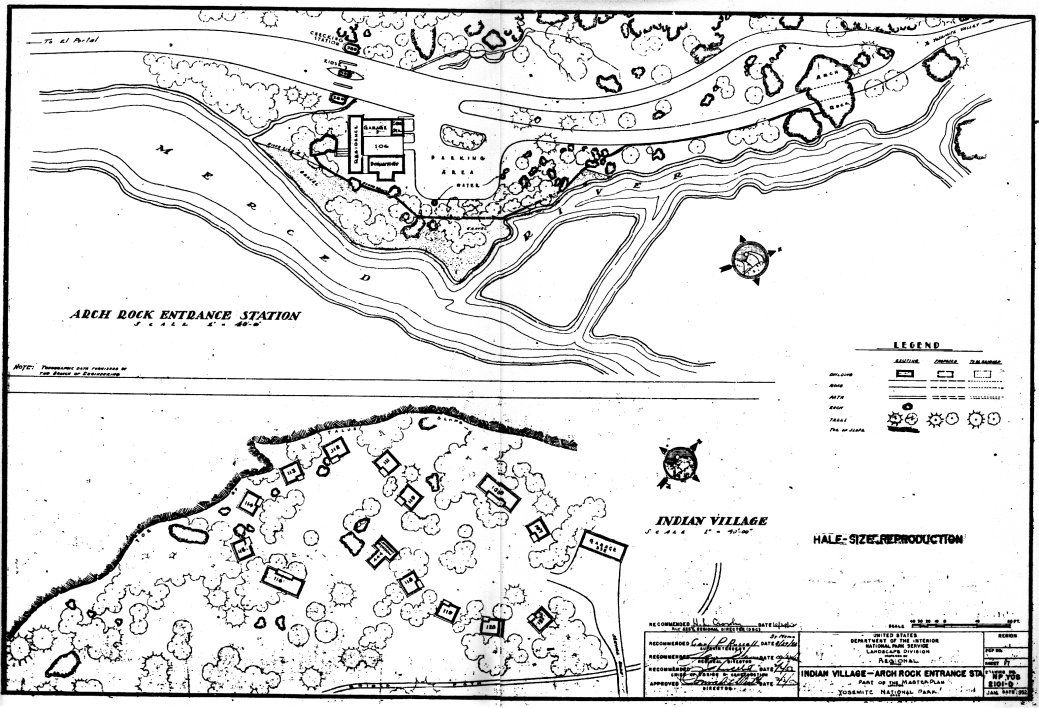

Illustration 148.

Arch Rock office.

[click to enlarge] |

Illustration 149.

Arch Rock comfort station.

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 150.

Arch Rock residence #106. Photos by Robert C. Pavlik, 1984. |

|

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 151.

Wooden truss bridge over Yosemite Creek above waterfall, enroute to Yosemite Point. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 152.

Cascade Creek Bridge, old Big Oak Flat Road. Photos by Robert C. Pavlik, 1985-86. |

[click to enlarge] |

The flood severely damaged the old Wawona Road from a point above the Bridalveil Fall parking lot to Old Inspiration Point. The park decided to limit repairs to reconstruction as a horse trail, and no longer maintain that route as a road. A new suspension bridge on the valley floor was rebuilt with material salvaged from the flood on the identical plan of the old structure but on a new site about 300 feet downstream. 34 In addition, repairs were needed on the wing walls and abutments of the Pohono, El Capitan, and Sugar Pine bridges. The flood of 1937 damaged or destroyed outlying trails and bridges as well as valley structures. Civilian Conservation Corps labor in 1937-38 was invaluable in ‘trail repair work, a force that would be sorely missed under similar circumstances in 1950.

During these years much new trail construction took place, including: new trail bridges at Wapama and Tueeulala falls on the north side of the Hetch Hetchy reservoir, one across the Middle Fork of the Tuolumne River, one across Illilouette Creek on the Eleven-Mile Trail to Glacier Point, one across Snow Creek above Mirror Lake, and a new horse bridge at Yosemite Fall. In 1939 laborers reconstructed the Vernal Fall Bridge of prefabricated steel with log veneer, and a year later reconstruction work replaced the old hewn-log truss bridge on the Nevada Fall Trail with log-covered steel plate girders.

i) North Valley Road Realignment Considered

By 1939 park officials were discussing possible changes of location and alignment for the valley’s North Road. One of the most dangerous spots in the valley road system lay where the North Road ran through the midst of the Yosemite Lodge development. There the public highway suddenly became a congested main street crowded with vehicular and pedestrian traffic. Because the main lodge needed replacement soon,

[34. Superintendent’s Monthly Reports, January-December 1938 and 1939, microfilm rolls #3 and #4, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

it seemed a good time to decide what to do about the road, which had to be moved either farther south or north.j) Completion of New Big Oak Flat Road

By 1940 the Big Oak Flat Road from Crane Flat to the valley floor had been completed. The first two miles out of the canyon from the All-Year Highway comprised the most difficult stretch of highway construction ever undertaken in Yosemite National Park. The project included the boring of three tunnels and the construction of three reinforced-concrete, open-spandrel arch bridges. The park converted the old route descending into Yosemite Valley into a one-way downhill scenic road. Visitors used it only until 1943 when a large rockslide made the road impassable to autos.

k) Bridge Work Continues in the 1940s

Work in 1941 included completing the reconstruction of the Nevada Fall Trail bridge; reconstructing the bridge across Cascade Creek on the old Big Oak Flat Road, which had deteriorated, to enable opening that road to one-way travel; and constructing a new trail across the Clark Range. Superintendent Frank A. Kittredge requested during this time the flagging of a trail between Glacier and Washburn points, in front of the Glacier Point Hotel, as a scenic naturalist walk.35 Kittredge also hoped that

whenever this emergency defense period is past, it will be possible to put some of the main line trails of Yosemite on a construction basis comparable to that of most of the other parks. . . . if we can just take advantage of some of the inspiration of some of this great back country, afoot or horseback, as is the Sierra Club, we are going to build up a group of nature lovers and conservationists which will form a bulwark of protection for our wilderness areas.36

[35. Memo for Park Engineer E. M. Hilton from Frank A. Kittredge, Superintendent 3 September 1941, in Box 83, Trails - 1941 to 1942, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

[36. Frank A. Kittredge, Superintendent to Richard M. Leonard, chairman, Outing Committee, Sierra Club, 1 October 1941, in Box 83, Trails - 1940 to 1942, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

|

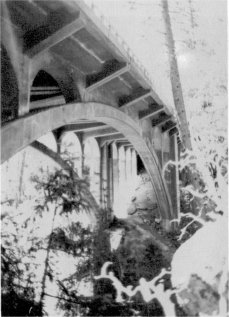

Illustration 153.

Tunnel No. 1, east portal, new Big Oak Flat Road. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 154.

Stone wall along new Big Oak Flat Road. Photos by Jo Wabeh, 1986. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

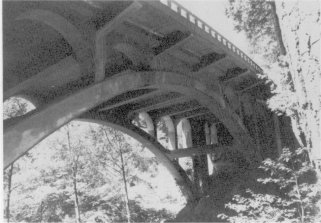

Illustrations 155-57.

Bridges, new Big Oak Flat Road. Photos by Jo Wabeh, 1986.

[click to enlarge] |

[click to enlarge] |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 158.

Road bridge over Tuolumne River. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 159.

South Fork of the Tuolumne River bridge abutment. Photos by Robert C. Pavlik, 1985. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 160.

Map of Yosemite National Park, 1948. Yosemite Research Library and Records Center. [Editor’s note: map by Della Taylor Hoss—dea] |

[click to enlarge] |

Workers in 1943 reconstructed the Yosemite Creek footbridge, which had collapsed. In 1945 they spent a great deal of time rebuilding bridle path bridges on the Yosemite Valley floor, including the three-span bridge at the foot of Yosemite Fall and a one-span bridge in the Lost Arrow section. In addition they rebuilt the two-span middle footbridge at Happy Isles. In 1946 replacement of the footbridge connecting Camps 7 and 16 got underway and replacement of the decayed footbridge near the fish hatchery at Happy Isles was completed. That same year progress continued on badly needed trail and trail bridge repairs. Crews rebuilt seven bridges in the vicinity of Echo Creek, Merced Lake, and Washburn Lake, including four short-span ones, and made the old Merced Lake Trail passable preparatory to closing the main trunk trail for bridge replacement. Work also proceeded on repairing the decayed Return Creek bridge.

Late in 1946 the bridge across Crane Creek on the Coulterville Road at Big Meadow collapsed. Work crews managed completion of a bridge across the Middle Fork of the Tuolumne on the Mather road and replacement of the Yosemite Creek bridge on the old Tioga Road. That year workers also accomplished replacement of Long Bridge and Twin Bridges across the Merced River on the Merced Lake Trail. In 1947 the footpath bridge on the Lost Arrow Trail, last replaced in early 1938, was again replaced, as was bridle path bridge no. 14, one or two miles above Mirror Lake.37

[37. Superintendent’s Monthly Reports, January-December 1943 to 1947, microfilm roll #4, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

After the Yosemite Valley Railroad was abandoned in 1945, another means had to be found to transport supplies into Yosemite Valley. The Yosemite Park and Curry Company purchased large trucks, which were unable to pass through Arch Rock. A serious traffic hazard resulted when the trucks were forced to bypass the rock going against the traffic flow. To remedy the situation, the arched portion of the rock was blasted out to permit passage of these vehicles. Small charges of dynamite were used to avoid breaking off unsightly chunks of rock.38

[38. “Arch Rock Enlargement, 1948,” in Box 78, Box A—NPS files, 1938-1953, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

l) Flood of 1950

The flood periods of 19 November, 3 December, and 8 December 1950 wreaked havoc on Yosemite’s road and trail system. Repair work in Yosemite Valley included repaving paved walks and footpaths, repairing bridle paths, replacing retaining walls, and removing fallen trees, silt, and other debris. Several bridges needed replacement of stringers and repair or replacement of abutments, railings, and decking. They included:

1. Old Village footbridge no. 20

2. Footbridge no. 25 (Mirror Lake half-log)

3. Footbridge no. 9 (Camp 16)

4. Footbridge no. 1 (Yosemite Creek near highway)

5. Horse bridges nos. 2-3 (Lost Arrow)

6. Footbridges nos. 4-5 (Lost Arrow)

7. Footbridge no. 26 (Mirror Lake)

8. Horse bridge no. 14 (Mirror Lake loop)

9. Horse bridge no. 10 (between Camps 9 and 12)

10. Horse bridge no. 8 (foot of Yosemite Fall)

11. Swinging Bridge no. 21

The El Portal road lost more than 700 lineal feet of walls undermined by the floodwaters, which fell into the Merced River. ‘The waters also undermined the pavement at two points and caused collapse of one road section. Repair work included construction of concrete rock fill to support the undercut pavement sections, replacement of pavement, restoration of washed-out shoulders, replacement of culverts, headwalls, and bridges at The Cascades, and replacement of retaining and parapet walls. Similar work followed on the Yosemite Valley, Wawona, Glacier Point, Big Oak Flat, Tioga, Lake Eleanor, and campground roads, including removal of rockslides, fallen trees, broken pavement, silt, and other debris. 39

[39. Flood Damage - Repair and Reconstruction Estimates - Floods of Nov. 19, Dec. 3, Dec. 8, 1950, in Box 11, Floods and Water Supply, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center. Reconstruction costs for these properties skyrocketed due to the lack of an inexpensive work force, such as the CCC, and postwar inflation affecting the price of materials. Because of the extensive flood damage and consequent need for haste in repair work, by the mid-1950s the park began using Bailey bridges of prefabricated steel parts. Snyder and Castle, “Draft Mules on the Trail in Yosemite National Park,” 10.]

m) Completion of the Tioga Road

Completion of the Tioga Road comprised a primary aim of the MISSION 66 road and trail program in Yosemite. Over the last several years, discussions had ensued over whether the central portion of the new road should be routed via the “high” or “scenic” line or along the general route of the old Tioga Road. Intensive studies involving discussions with various cooperating groups, the Secretary of the Interior, and other interested parties became fraught with controversy. Objections arose specifically from certain conservationists and the Bureau of Public Roads after it had been decided to proceed on the route selected and approved years earlier. Changes to meet improved safety standards met resistance from such people as David Brower, executive secretary of the Sierra Club, and nature photographer Ansel Adams. The Bureau of Public Roads believed that a wider road with wider shoulders was necessary so that cars could pull off the road in emergencies. The Park Service, meanwhile, wanted a safe width of road with narrow shoulders and with turnouts only where the terrain permitted to avoid scars from cuts and fills as much as possible plus higher costs. The matter was finally settled in favor of the two-foot shoulders with few turnouts except for one section where the shoulder had to be widened to provide the necessary stability.40 Conservationists, however, continued to object to the blasting and gouging methods used and the resulting scars on the face of glacially polished granite surfaces at Olmsted Point.

[40. Wirth, Parks, Politics, and the People, 359-60.]

Actual construction of the new central section began in 1957, and it officially opened to the public in June 1961. The work had progressed with due regard for preservation of scenic values. It turned into an outstanding park road, carefully designed to display to their fullest the dramatic assets of the Sierra Nevada. The highest trans-Sierra crossing, it is well supplied with overlooks and interpretive signs. Sections of the old Tioga Road were retained, such as that leaving the new road just east of the White Wolf intersection and winding down to the Yosemite Creek campgrounds; another short section climbs over Snow Flat to the May Lake Trail junction. Shorter sections still serve campgrounds along the old road.

n) Flood Reconstruction Work Continues

In 1952 workers completed reconstruction of the Yosemite Fall bridge, partially washed out during the 1950 flood. By 1952 Park Service officials had decided the new Yosemite Village would receive early attention. Director Wirth at that time earmarked $80,000 for immediate use (1953) in planning and constructing roads and parking areas.41 In 1955, the most severe flood in Yosemite’s history forced closure of roads into the park. Again floodwaters washed away large sections of the El Portal road, resulting in months of extensive repair work. In 1957 crews placed steel decking on the Vernal Fall bridge. By the end of 1960 the Merced River bridge stood complete with the approaches prepared for paving and the contractor had started work on reconstruction of the Sentinel Bridge.

[41. Russell, notes taken during conference on 30 July 1952, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

|

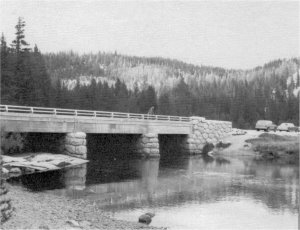

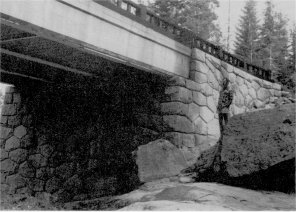

Illustration 161.

Road bridge over the South Fork of the Merced River near Wawona. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 162.

Controversial section of Tioga Road, northeast of Olmsted Point. Photos by Robert C. Pavlik, 1984-85. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 163.

Ruins of Chilnualna Fall ranger patrol cabin. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 164.

Single stringer log and plank foot/horse bridge on trail between Chain Lakes and Chiquito Pass. Photos by Robert C. Pavlik, 1985. |

[click to enlarge] |

o) MISSION 66 Provides Impetus for New Big Oak Flat

Entrance Road

The second most important section of the park’s road system scheduled for completion under MISSION 66 was the seven-mile section of the old Big Oak Flat Road between Crane Flat and Carl Inn connecting with state route 120. The old stagecoach route would be retained as access to the Tuolumne Grove. In 1961 laborers started clearing the alignment for the new Big Oak Flat entrance road and parking areas. That entailed clearing and removing trees and brush within the right-of-way for the new road, between Crane Flat and the vicinity of Hazel Green Creek. The park decided to relocate the road when it determined that improvements to the existing road, including some realignment to straighten out dangerous curves, could not be made without damaging trees in the Tuolumne Grove. The new route ran along the western boundary of the park, connecting with state route 120 in the vicinity of Carl Inn. The park retained the historic road to the big trees in the Tuolumne Grove as a downhill, one-way road out of the park from Crane Flat.42

[42. Superintendent’s Monthly Reports, January-December 1948 to 1961, microfilm rolls #4 and #5, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

Construction within the national parks increased tremendously during the 1930s, particularly with the added help of emergency public works personnel. War conditions of the early 1940s tended to slow the process, but the pace of construction in Yosemite National Park into more recent times continued to be impressive and cause new concern about effects on the resources and the quality of the visitor experience. MISSION 66 objectives calling for the modernization of existing facilities, additional development of accommodations and services in sections of the park outside the valley to relieve congestion, and removal of all but certain critical operating functions out of the valley would result in major governmental and concession-related physical development in the latter part of this period. The decision to bring more development into the Yosemite high country, resulting in improved roads and construction of new campgrounds, picnic areas, comfort stations, and visitor interest areas, such as the Yosemite Pioneer History Center at Wawona, has not solved the problem of overcrowding but helped to some extent in broadening the visitor experience and exposing people to the variety of attractions in the park.

1. Season of 1931

Construction projects accomplished during the 1931 season included,

on the Big Oak Flat Road: Establishing a new entrance station at the park line on the Big Oak Flat Road on a site formerly occupied by a California State Automobile Association tow camp. This action placed a ranger in the heart of the Rockefeller timber purchase and close to the Tuolumne Grove;