[click to enlarge]

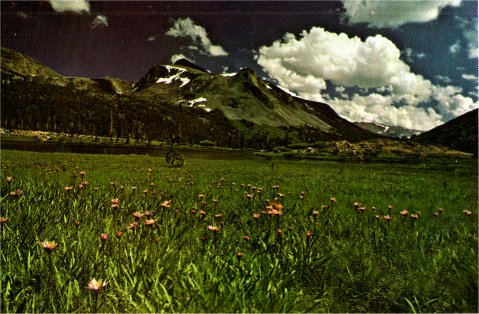

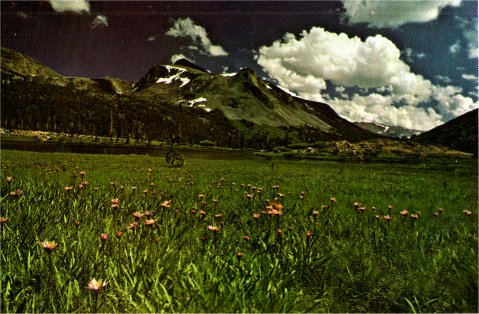

Meadow Asters and Mt. Dana,

Aster alpigenus ssp. andersonii

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Wildflower Trails > Tree Line and Above >

Next: Plant Names • Contents • Previous: Subalpine Belt

When one stands at the high, windy crest of Tioga Pass’s 9,941-foot summit, it is easy to believe that the upper limit of vegetation has been reached. True, the White Bark Pines (Pinus albicaulis) which are here replacing the lodgepoles and hemlocks, will struggle up another thousand feet on the surrounding peaks until they lie prostrate on the rocky slopes, flattened and sculptured by the buffeting wind of the summits, But surely nothing as delicate as wildflowers could grow in this seeming wasteland of rock a region where winter lasts from September to mid-July and where a killing frost can occur at any time. And yet they do! In the area above tree-line, generally referred to as the alpine zone, about 170 different species of flowers, grasses and sedges have been identified.

One of the most rewarding of alpine rock gardens is the great peak of Mt. Dana (13,053 feet) which rises immediately east of Tioga Pass, just across the open expanse of Dana Meadows. Few areas anywhere can surpass its display of high-elevation flowers, from the lush fields of deep blue lupine at its base to the amazing stands of sky pilot on its lofty summit. In between occurs a rich panorama of other genera which come into bloom in succession from early July to the middle of August and which can provide for the flower enthusiast a rare day of discovery on the westerly slopes of this one mountain.

A trail of sorts from the Tioga Entrance Station leads directly toward the peak itself, passing several idyllic tiny lakes nestled into lawn-like meadows brightened by red heather, yellow potentilla, lavender asters, short-stemmed goldenrod. Approaching the mountain slopes, our little trail strikes boldly upward, climbing determinedly above the broad sweep of meadowy landscape which lies on either side of the Pass.

Here, at the start of our climb, we walk through masses of flowers which, in

[click to enlarge] Meadow Asters and Mt. Dana, Aster alpigenus ssp. andersonii |

As we climb higher, the trees become fewer and we reach the first of the open, gravelly slopes which mark the definite transition known as tree line. About here, in the first week or two of July, appear the earliest of the mountain’s floral displays— before the lush gardens of the lower slopes come into bloom. Certain to be noticed are the low, circular mats of Spreading Phlox (Phlox diffusa), with their 5-petalled blossoms in shades of pink, lavender or white, which we have seen before around Yosemite Valley’s rims.

Not so likely to be seen, however, is one of the most amazing of all the Park’s flowers—the tiny Steer’s Head (Dicentra uniflora). This relative of the bleeding heart of Yosemite Valley grows on a short stem, 2 inches high, with a single pale pink blossom only 1/2 to 3/4 inch long. This blossom is an amazingly precise caricature of the bleached skull of a steer—the long snout, empty socket eyes and up-curving horns creating a lasting impression. Nearby are one to three basal leaves dissected into many small lobes, lying flat on the ground. The flower is so small it is very hard to see from normal eye level and may require careful searching. However, once found, the thrill of discovery is ample reward for the effort. Look for it in fine gravel near melting snow banks which keep the area moist. They are in bloom only a week or so, but may be seen in a number of places in the Park between 6,000 and 10,500 feet, when conditions are exactly right—such as near the Upper Gaylor Lake and on Illilouette Ridge’s western slope.

The trail to the summit climbs across beautiful grassy meadows, tilted at an angle which produces miniature waterfalls in the small streams singing their way through them. Above these, we reach a rocky plateau where alpine gravel gardens are at their best, normally about the end of July.

In crevices among those rocks, look for stands of the White or Alpine Columbine (Aquilegia pubescens) on straight stems 8 to 18 inches high, with several blossoms at the tips. Each petal ends in the typical spur, a repository for the nectar which makes these flowers great favorites of hummingbirds, sphinx moths and large bumble bees with long tongues. This species hybridizes readily with A. Formosa, of the lower elevations, so we occasionally find tones of cream to yellow to pink to lavender among the white. Unlike its lower elevation relative, though, this columbine carries its flower heads erect on the stems rather than in a drooping posture. One of the most prolific areas in which to find it is the talus slope under the Lying Head, on Mt. Dana.

As we cross the plateau, we are made aware of the predominantly low profile of the plants growing there. All have contrived the rather typical shapes of dense mounds of leaves or low mat-like herbage which enable them to survive the extremely low winter temperatures by burying themselves under thermal blankets of snow. Their low forms also present the least possible surface to the severe winds of the high places, thus lessening the (frying effect of this continual turbulence.

One of the more spectacular of these plants is the Alpine Penstemon (Penstemon davidsonii), a memorable purple-violet flower with an inch-long tubular form. It occurs in masses of blooms from a creeping mat of dark-green, small, round leaves and is found commonly between 9,000 and 12,000 feet. Preferring rocky, gravelly locations, it often snuggles against the leeside of an outcrop which gives added protection from wind. This plant blooms almost all summer, from the period soon after the snow hanks are gone until the first winter snows begin, perhaps in September.

Another delightful blossom, its bright colors adding to the brilliance of the region, is the Alpine Buckwheat (Eriogonum ovalifolium var. nivale). These plants are of tire type frequently known as “pincushion plants,” and the allusion is obvious. From rounded mounds of silvery-white leaves, so firm they resist even the imprint of a carelessly placed hiking boot, the bright little yellow or rose-colored blooms rise on short stems like decorative pins thrust into an old-fashioned pincushion. The flowers are actually about 1/a inch long, closely packed into spherical heads some 3/4 inch across the compact form of the plant is reinforced by a densely woody structure of branches, making it well suited to live for many years in the severe climate of the alpine zone. You will find it a frequent companion on climbs into Yosemite’s summits, well above tree line.

The so called daisies are represented here in this land of the sky, too. Frequently seen in this plateau region on Mt. Dana and in other comparable sites is the Alpine Daisy or Fleabane (Erigeron compositus var. glabratus). A dwarf, cushiony plant with a mass of Ian like, hairy, multi-lobed leaves, the short stems rise 2 to 6 inches, with a single blossom on each. The flower is in the traditional form of a daisy—white rays surrounding a yellow center—and is only about an inch in width. An arrangement of these delicate little blossoms on the granite gravels of a lofty alpine garden will be remembered and cherished as an example of nature’s utmost care with even the smallest of her creations. In the same general area, you may expect to find a diminutive lupine with pale lilac to white flowers on stems 2 to 4 inches high (Lupines lyallii var. danaus). This is Dana’s Lupine, named for Mt. Dana, which in turn was named for the eminent American geologist, James Dwight Dana.

Now our trail heads for the 13,000-foot summit of the peak itself. As we leave the plateau and climb over the colorful slabs which make up the mountain’s topmost 1,000 feet, we follow occasional splotches of yellow paint across the rocks. No real trail penetrates these heights, and the thin air makes it necessary to proceed slowly. There are advantages in such a slow pace, though, for there is much to see. Mt. Dana raises its lofty crown well above its neighbors; it is the most northerly peak exceeding 13,000 feet in all the Sierra.

Along this last part of our climb, and especially on the summit, the view unfolds in every direction. Mono Lake, to the east, lies almost 6,500 feet below and 10 miles distant, a circular azure mirror reflecting the clouds, like a piece of the sky itself in a setting of silvery-gray ridges. Directly beneath us, the Dana Glacier sprawls across the end of Glacier Canyon, its moraines cradling the turquoise water of Dana Lake, almost 2,000 feet below. To the south rise the twin summits of Mts. Lyell and McClure, their glaciers gleaming in the sunlight. Westward, the long expanses of the Dana and Tuolumne Meadows roll away from our feet to merge with the far away domes and peaks of the area near Lake Tenaya. Our view to the north comprises a bewildering array of crests and valleys, brick-colored with the metamorphic rocks of this part of the Sierra. Saddlebag Lake makes a focal point of interest in the middle of a landscape which extends to the mountain summits at the northernmost boundary of Yosemite National Park.

Not far below the summit we see the first blossoms of a plant which is characteristic of the rocky peaks above tree line. Alpine Gold (Hulsea algida), is named. First collected here on the slopes of Mt. Dana in 1865, it may also he found on many Sierran summits between 10,000 and 13,000 feet. It looks somewhat like an oversized dandelion, producing a brilliant yellow blossom some 2 inches across, one flower at the end of each stem which may rise 4 to 16 inches. The leaves are long and slender and are sharply toothed, rising from the base of the stalks. These stalks, and the flower heads, are sticky and exude a pungent odor resembling balsam. Far above tree line, in the rusty tones of the metamorphic rocks which comprise much of the peak of Mt. Dana, these bright yellow orbs are a visual delight. They form a spectacular color contrast to the vivid red, orange and gold of the lichens which flourish on the rocks of these elevations—rocks which often form landscaped walls surrounding the tiny plots of humus for the hulsea gardens.

Mt. Dana reserves its most remarkable floral treasure for the last. Only those who, like pilgrims seeking a remote shrine, trudge all the way to the top are privileged to behold the Sky Pilot (Polemonium eximium). The common name comes from the slang term for one who leads others to heaven; appropriately, it was given to a plant which is found only on or near the tops of the highest peaks. Its pale blue-lavender blossoms, 5-petalled, are crowded together in compact heads, 2 to 3 inches wide, at the tops of stems rising 4 to 12 inches. The leaves appear as small green cylinders and are divided into many tiny leaflets, 3- to 5-parted. The entire plant is somewhat sticky, exuding a sweet, musky odor which seems to pervade the general area. Not the least remarkable characteristic of the polemonium is its ability to flourish in crevices of the summit rocks which appear to offer almost nothing in the way of viable soil. Yet flourish it does in its sky garden, a glorious reward for the weary climber as he stands at last on the mountain top. Polemonium is appropriate to its setting; it is a creature of the sky, the drifting clouds and the summit wind.

While Mt. Dana offers a comprehensive course in the flora of the alpine zone, there are several other flowers of borderline occurrence (i.e., growing just at or immediately below tree line) which are of interest too and should be included here. An especially likely area to look for them is near the little ghost town of Bennettville, a mile north of the highway as it skirts Tioga Lake just east of Tioga Pass. A remnant of the original Tioga Road leads to the town site which consists today of but two wooden buildings, quietly slumbering to the music of a mountain stream. Along this stream, rising from some small lakes another mile north, and in the lush meadow below the town site, rich flower gardens bloom under the bright sunshine—and occasional showers—of late July and August. Many of these flowers we have encountered before, or we have met closely related species. There are several, however, which are new to us and deserve special comment.

Perhaps the most showy of these is the Alpine Monkeyflower (Mimulus tilingii). At the stream margins especially, but wherever there is assured wetness, this brilliantly yellow little flower appears in masses. As with all monkeyflowers, its little face, about an inch across, has the unique form which suggests such a name, the lower lip drooping with heavy jowls. The flower’s throat is almost closed by two brown-spotted, or “freckled” ridges. Beneath the mass of yellow blooms is a lush backdrop of bright green, inch-long leaves. This little plant thrives in and near icy streams, forming colorful mats among the warm-toned rocks of the banks. There is a particularly showy colony near the opening of the mine tunnel west of the town site, where a stream of ice water gushes continuously from the tunnel’s mouth.

The old, historic road which serves as the trail to Bennettville is a likely place to look for an attractive member of the stonecrop genus, Western Roseroot (Sedum rosea ssp. integrifolium). It clambers over rocks where moisture collects from higher slopes, sometimes forming fringes across the margins of ledges. On stems 2 to 8 inches high, tightly clustered small red flowers make rosettes of bright color. The offsetting green of the small leaves, which are thickly distributed along the stems, is a pleasing color contrast. While the tiny flowers are still in bud, surrounded by the green calyx-lobes, the effect is especially charming—like “caviar in a green jade bowl,” Mary Tresidder described it. Roseroot is a flower of early summer—late June or early July—in the High Country. If you look carefully you will find it often, seemingly enjoying the matchless scenery of its homeland from a sunny, rocky eminence.

If one wanders along the stream (Mine Creek) above the town site of Bennettville, there is a good chance of meeting in late August one of the most delicately beautiful of residents of the High Country, Grass of Parnassus (Parnassia palustris var. californica). On slender, grass-like stems, 6 to 15 inches high, the lovely, cream-colored blossoms are borne singly. The 5 petals have prominent green veins and are smooth edged; the entire blossom is an inch or more across. At the base of the thin stem is a tuft of heart-shaped leaves, an inch long, on extended petioles or stalks. It favors wet areas and can most frequently be found along the margins of streams, though nowhere in abundance. The whole plant presents an elegant aspect, fittingly created to grace the landscape of Mt. Parnassus, mythological home of the god Apollo.

Other flowers demand our attention as we wander through the High Country landscape on a dreamy summer’s day, and they too will linger in the memory of such an experience. There will be the Shrubby Cinquefoil (Potentilla fruticosa), with brightly yellow flowers, like single roses, decorating generously a low bush of many branches and masses of tiny, needle-like leaves. Tall stalks of Valerian (Valeriana capitata var. californica), its small white flowers clustered into heads 2 inches wide, seek out areas of early moisture. Delicate little Campion, or Catchfly (Silene sargentii), produces small white tubular blossoms with flared petals, preferring rocky crevices. If you look closely in damp, shady areas near rock walls, you may be fortunate enough to see the strange little Mitrewort (Mitella breweri), on slender stems from round basal leaves, with tiny green petals divided into a needle-like geometrical design. Many of our old friends from the subalpine zone are present too—scarlet paintbrush, pink asters, purple whorled penstemons, golden tones of senecio and wallflower, white heather, the brick-red of bryanthus (red heather), tall, white button parsley, orange-toned columbines, magenta mountain-pride, pink elephant heads, lavender wild onions, lupines in assorted shades of blue and violet. And more, many, many more! Early August is the moment of truth for the floral regions at tree line and above. The business of blooming and then setting their seeds must be attended to promptly, for the days are dropping away like autumn leaves and winter can begin in September. So the urge to bloom is seen everywhere, with magnificent results!

Here, then, is the last act in the drama of spring’s pilgrimage from the foothills, which began in March. For six months we have been privileged to observe her progress up the mountain slopes of the Sierra, across the canyons and meadows and ridges of Yosemite. Appropriately, she rings down the curtain for this year with a spectacular show of color and form and diversity of species, displayed on a stage of unparalleled grandeur among the peaks and high glacial basins.

Though we may have regrets when September turns the meadows to gold and the tiny leaves of the dwarf bilberry flame in the grass, there is deep satisfaction in knowing that the magnificent production will be re-staged next year. Anyone fortunate enough to see at least some of spring’s performance can breathe a little prayer with Mary Tresidder, “I hope I may pass that way again.”

Next: Plant Names • Contents • Previous: Subalpine Belt

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_wildflower_trails/alpine.html