[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Big Oak Flat Road > The Big Oak on the Flat >

Next: Ranches and Rancheria • Contents • Previous: Jacksonville

The grade that leads up from the town of Moccasin to Priest’s is a dilly, whether called by its earliest name, Moccasin Hill, Rattlesnake Hill, Big Oak Flat Hill or the more familiar “Old Priest’s Grade.” Somehow or another any vehicle traveling its stark contours must hoist itself 1575 feet in a matter of two miles.

The new Priest’s Grade on Highway 120 which, so transitory is fame, even now is old and is subjected to reconstruction every year or so, takes about eight miles to reach the same point.

The ascending travelers of yesteryear all walked the full distance of Moccasin Hill as it was difficult for the teams to pull even an empty stage. Fortunately, a spring issued from the mountain about half way up the old grade. Miners, weary under heavy packs, found odd companions as they rested here. Sometimes the welcome patch of shade held strange Miwoks from the mountains returning from a hunt; their women, burdened with deer meat covered with dust and flies, were unable to rise with their loads unless pulled to their feet by the men who carried simply bows and arrows. The hunters never objected to assisting their helpmates to that extent. Again the resting miners might find themselves in company with a circuit riding clergyman, a traveling priest, or even an occasional masked bandit with a predatory eye on the buckskin bags of gold dust so universally carried. One rather impulsive highwayman killed a perfectly run-of-the-mill traveler under the impression that he was the tax collector. In staging days a small building containing tools and ropes was installed near the spring. No person nor vehicle going uphill passed without pausing. As automobiles gradually replaced other modes of transportation the cars all stopped here to pant and both car and driver took on all the water they were capable of containing.

It is no longer necessary to stop at the spring. Any well-driven modern car in good condition can, in the cool of the day, go straight up. Many automobilists (including ourselves) prefer it to the numerous curves on New Priest’s Grade which are all too often traveled in discomfort and from which one is apt to emerge with one’s inwards out of alignment.

The canyon lying between the old and new grade is called Grizzly Gulch and is filled with heavy brush, notably toyon. On the north slope about opposite the spring is a subsidiary gully humorously named Cub Gulch. The small mines visible on the north slope were well known as the Eureka and the Grizzly belonging to Charles and Edwin Harper of Big Oak Flat. From them some of the most beautiful exhibition specimens of leaf gold in the Mother Lode have been taken.

Immediately at the top of the grade was Priest’s Hotel or Station founded in 1855, of which the mainspring and motive force seemed to be its handsome Scotch hostess. She was, in the first and hardest period, Mrs. Alexander Kirkwood and with her husband managed to place “Kirkwood’s” in an enviable position among the hotels of the country. After Mr. Kirkwood died in 1870 his wife eventually married a fine-looking Kentuckian, William Priest, and the attractive couple carried on the old tradition. Many of their guests were journeying by wagon to Yosemite. They came at all hours for it was considered worth traveling long after dark to arrive at Priest’s Hotel.

At that period there seems to have been no employment thought suitable for a young girl except some type of domestic work where she might be constantly under the supervision of an older woman. A job in a superior hotel was at the head of the list.

[click to enlarge] |

Eunice Watson Fisher of Big Oak Flat, was kind enough to give us a word picture of life at the top of the grade. In part it reads: “Mother worked for the Priests three months out of the year and we all stayed there during that time. I was what you would call a ‘bull cook’ when I was only thirteen years old for which I received five dollars a month with room and board. Later I was a real cook for which I was given twenty-five dollars. We used to get up at all hours of the night—just whenever the travelers arrived. Mrs. Priest would call us herself. Often we’d hear, ‘Whoo hoo, girls! A party of eight.’ Then we’d get out of bed, dress, and cook up anything the people ordered and it wasn’t easy, especially if we had had a busy day. But that didn’t matter. There were no set hours of work in those days.”

Eunice Fisher was most loyal to the establishment. “I was very fond of my employers,” she went on, “and when Mr. Kirkwood died I helped to lay him away. We didn’t have funeral parlors to take care of such things. Young though I was the responsibilities and sorrows of life were never kept from me. We children of the pioneers helped with everything to the best of our ability.”

John Ferretti, who lived near by in Spring Gulch, was completely familiar with Priest’s Hotel. As a boy of fifteen he was general handyman, errand boy, and the nearest substitute for a modern bell hop considered necessary in the ’90s. “It was a high-class establishment,” he assured us, “and well known from one end of the state to the other. The cuisine was excellent and Mr. and Mrs. Priest were fine people. It was a privilege to know them.”

William C. Priest was a man of affairs in the county also and became a director of the Great Sierra Stage Company’s Yosemite Run when it was re-incorporated in 1886 and was superintendent of construction of the Tioga Road. The couple were general favorites. The new Priest’s Grade was not opened until about 1915 and, although Mrs. Priest had died ten years before, it was formally named in her honor.

The establishment is maintained by Mr. and Mrs. Joseph L. Anker. Mrs. Anker is a grandniece of Mrs. Priest so it may be said to be “in the family.” It is still Priest’s Station and the old and the new grades meet directly in front of the office so that many cars stop with a sense of achievement on the part of the driver as it is certain that every horse-drawn stage and freighter has done since the roads opened.

Eunice Watson Fisher watched the coming of the automobiles. She wasn’t too favorably impressed. “Give a horse time and he’ll get to the top,” she remarked. “Some of the old cars never did get there.”

Priest’s is on the height between Grizzly Gulch and the canyon of Rattlesnake Creek. Originally the latter was allowed the privilege of going down its own canyon but Rattlesnake, what with mines and miners, was admitted to be a dirty little stream and a detriment to the relatively pure flow of Moccasin Creek. No objection was made to the project of having it detoured for the use of several mines. So its waters were conveyed into Grizzly Gulch by means of a tunnel beneath the highway in front of Priest’s, utilizing one partially dug by miners in search of pay dirt many years ago. After passage through the mountain Rattlesnake Creek comes out to sunshine in the toyon-covered box canyon, finding its way into the Tuolumne River even more directly than before.

At Priest’s Hotel a road swings in from the south. It leads to Coulterville about ten miles away. In freighting days a tiny, scattered settlement known as Boneyard strung along the road about half way between the two places. Its name was bestowed because of a large number of Indian bones which, the story has it, came to light when any excavating was done. On this same road about three miles from Priest’s, at Spring Gulch, lived Frank Ferretti, brother of “Happy Joe,” with his family. The rock wall still standing farther along beside the road was built by Frank. The James Lumsdens, another prominent family of Tuolumne County, lived at Boneyard. So also did the German roadhouse keeper, Ike Meyers, with his 300 pound wife. These families and several others divided their shopping and social activities between Coulterville and Big Oak Flat, so their small cluster of houses should not be omitted from the roster of settlements along the Big Oak Flat Road.

East of the summit the highway is slightly farther from Rattlesnake Creek than was the original road which kept faithfully to the edge of the water. A miners’ settlement called “Rattlesnake” existed briefly in the 1850s. Three-tenths of a mile from Priest’s, Slate Gulch comes in from the left. A high flume used to carry the waters of the Golden Rock Water Company across the road at this point, releasing them into a ditch on the opposite side of the creek. where they flowed down into Mariposa County.

The road wound through the open canyon, bordered with a hodgepodge of miners’ tents and temporary shelters, until it emerged to the awe-inspiring vision of the big oak on the flat. In the first few years of the white man’s invasion of the “California Mountains” the trees were apt to be large but widely spaced with no underbrush. Each year the Indians burned the grass to facilitate hunting and also because they had found it prevented fires hot enough to ignite the acorn oaks. The custom was an effective deterrent to the growth of small bushes and to the propagation of young saplings. The scattered grove shading the gravelly flat was composed of magnificent trees but the “Big Oak” was king of them all, a giant both in height and girth.

Here, in the fall of ’48, came James D. Savage. He was a strange young man and beyond all doubt a brave and competent one—best remembered as the commander of the Mariposa Battalion which entered Yosemite Valley and conquered its belligerent Indians in the spring of 18511.

Savage had been much associated with the Indians in his home state, Illinois, and on his arrival in California affiliated himself with the natives of the Sierra Foothills. He spoke five Indian tongues, some of them as well (we are assured by an old comrade) as the Indians themselves. He secured safety and trading privileges with the most important tribes by taking a wife from each. He never became part of an Indian village as the fur trappers sometimes did, but remained with his own projects keeping his Indian intimates with him; trying to guide their actions and to stand between them and trouble. It was not particularly altruistic as he fully intended to profit by their services, but he was concerned with their welfare and had probably more influence with them than any other white man.

There seems to have been but little exact personal information about Savage available. His age was any man’s guess; because of his effortless strength and tirelessness his stature was usually presumed to be above average; his hair was called blonde. Dr. Carl P. Russell questioned an old Indian woman (the only person then living who had ever seen him) and gained the information that he always wore red shirts, but little more as to his appearance. So it was with great interest that we read the diary of Robert Eccleston, who served under him in the Mariposa Battalion, which gives at the end a short description of this almost fabulous character: “He is a man of about 28 years of age, rather small but very muscular & extremely active, his features are regular & his hair light brown which hangs in a neglege manner over his shoulders, he however generally wears it tied up. His skin is dark tanned by the exposure to the sun. He has I believe 33 wives among the mountain females of California, 5 or 6 only however of which are now living with him They are from the ages of 10 to 22 & are generally sprightly young squaws, they are dressed neatly, their white chemise with low neck & short sleeves, to which is appended either a red or blue skirt, they are mostly low in stature & not unhandsome they always look clean and sew neatly.” This complimentary picture is partly corroborated by an unknown “Robert” who, in 1850, wrote to his wife from Sonora: “Generally the Mexican women have bad figures, but the Indian girls are slender and strait as arrows. . .”2 Eccleston continues: “The major has a little house built for their accomodation. Major Savage is now connected with Col Freemont & Capt Haler3 in the contract for supplying the Indians with provisions.”

In another paragraph Eccleston gives this additional information: James D. Savage emigrated to the west with Col. John C. Fremont “on his Expedition of Survey of this Country.” He saw action as an officer during the California revolution. He ingratiated himself with the Indians and became a trader. He took a contract for collecting “the Freemont stock of cattle” and afterward for digging the race for Capt. Sutter in which James Marshall discovered gold. He continued trading until late spring when it was possible to ascend the mountains. He then “worked his Indians” until uprisings among the nearby tribes led to the formation of the Mariposa Battalion.

When it became known that gold was all around him for the taking James Savage had been as well equipped as any man in the mountains to make a fortune. His Indians were amazed that a little work (done for the most part by their women) in gathering the heavy golden dust should be so delightfully productive of food and tin cups and dirty shirts and blankets. He accumulated in barrels gold dust and nuggets that assumed in the telling legendary proportions.

But his dusky in-laws were not emotionally organized to live peaceably with the miners who were not themselves noticeably self-controlled. A miner knifed an Indian who retaliated much more efficiently. And Savage took his protegees away—higher in the mountains.

He was only in the flat of the big oak a short time but because of him it received its first name “Savage’s Diggings.”

Rufus Keys, a young prospector, is supposed to have spear-headed the invasion of some six thousand miners who succeeded Savage on the flat. They found a gold-bearing gravel bed two to twenty feet thick—far too much to work out in a few months and leave. The place was so rich that according to Eugene Mecartea, claims were limited to ten feet square so, unless the owner lived in a tent, his shelter was rarely where he worked. Later the miners’ convention of 1851 allowed more generous holdings. A rather childlike condition of perfect trust prevailed during the first year at the diggings. Stealing was unknown. In spite of the fact that it is a hackneyed statement and appears in most publications dealing with the mining camps, we need not learn this fact at second hand. John R. Maben wrote to his wife November 15th, 1849: “. . . “There is no such thing as stealing here men leave everything no matter what it may be where he was using it even their Gold dirt they will leave it on a rock or in their boxes where they work it and be gone half the day.”4

As cold weather came on houses were needed and there was but little in the way of small timber with which to build. The following description is completely typical although it happened to be written a few miles away. It is given because Jason Chamberlain, from whose diary it comes, was one of the best-known residents of the Big Oak Flat Road. His story will be told later. A few words are illegible but the statement is plain enough.

“Commenced building a place to sleep or in other words a house most of the houses here are cloth but we have no cloth nor means to get any fifty cents is all that remains of our scanty supply between Cutes, [illegible], Chaffee and self so must do as they used to before cloth was invented We select the mountainside to build digging down some six feet to make it level we have nearly three sides inclosed we put [illegible] in front and run rafters back into the bank to support the roof We throw pine boughs on the rafters and cover the boughs with dirt build a chimney in one end and fix a place to sleep by laying logs on the ground and covering them with boughs one bed answering for five of us our house is now comfortable and if we have no rain will be very comfortable much more than tents in warm weather

April 16, 1851

“Commences raining which prevents our work. A (sic) rains hard all day and our house stands it finely until about 9 oclock evening then it comes down through by bucketsfull pretty well thickened with mud Now we have a fine time we stand it awhile till we are completely drenched we then repair to a tent that is deserted which leaks about as bad as the one we left but the water that comes through is clean and that makes it the more endurable four of the party find places to lie down and I find a bucket to sit on and with my blanket over my shoulders soon fall asleep but do not sleep near as sound as I have in days of yore in the land of feather beds”

By the approach of winter in ’49 the diggings were thick with such uninhabitable shelters. The miners had, of course, everything to do for themselves—no matter how foreign to their former habits—cooking, washing, nursing, even sewing.

Wilton R. Hayes wrote from the California mines to a friend in New Jersey: “I have just completed the astonishing feat of making a pair of pants. And I defy all the tailors in Nottingham to make a pair that will come as near like the negro’s shirt, touching nowhere. I was led to this desperate undertaking by seeing others do it.”

Among other unusual but necessary accomplishments every miner was obliged to be his own lawyer. That he took it seriously the following copy of an original document will bear witness:

“This is to certify that I have Sold to Luigi Noziglia my interst in the lot that have Sold to Mr Manuel Flores on account that Mr, Manuel Flores hase not appier withing Six Months from that time that Sel was made I sel to L. Noziglia the above Said mention person for Sum Ten Dollers to me paide and

Tigh nechuer My Mema

M. Noziglia” [Undated]

There were a few skirmishes between the miners and the Indians who either lived on the spot or came in season to gather acorns, evidenced by a large stationary mortar rock with many grinding holes north of the road at the entrance to the town. The affairs, in which a few arrows and pistol shots were let loose happily and at random, resulted in little but a pleasurable relief from monotony as far as the white men were concerned. There is, however, a story that some Indians were killed in a fight and buried across the trail from the big oak and that, peace being made a day or two later, their friends were permitted to exhume the bodies and take them elsewhere for burial according to tribal rites. If so the Indians seemed to bear no grudge and this, as far as we knew, ended real hostilities between red man and white along the Big Oak Flat Road.

More deadly than Indians was the “fever and ague” that attended the damp and steamy mining camps during the summer. The ailing men would pay “an ounce of gold for the visit of a medical man.” Often they paid three times that much for a single dose of medicine.5

Even so the mining camp grew and prospered and became a settlement.

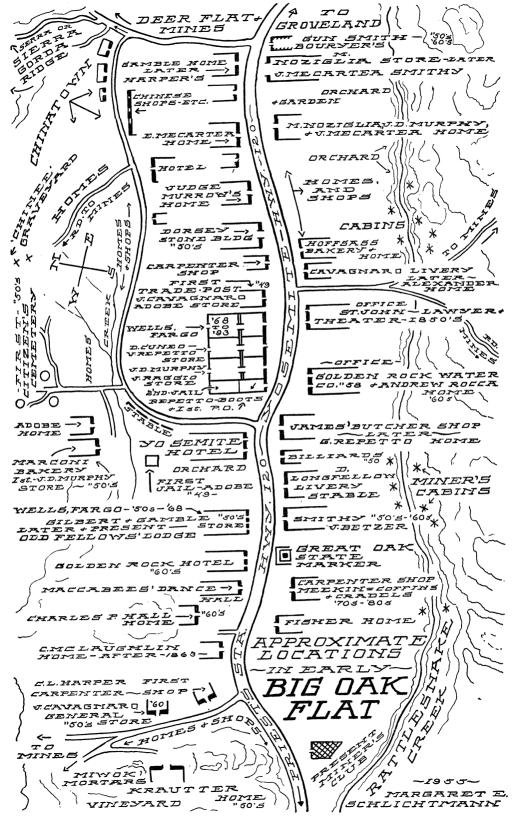

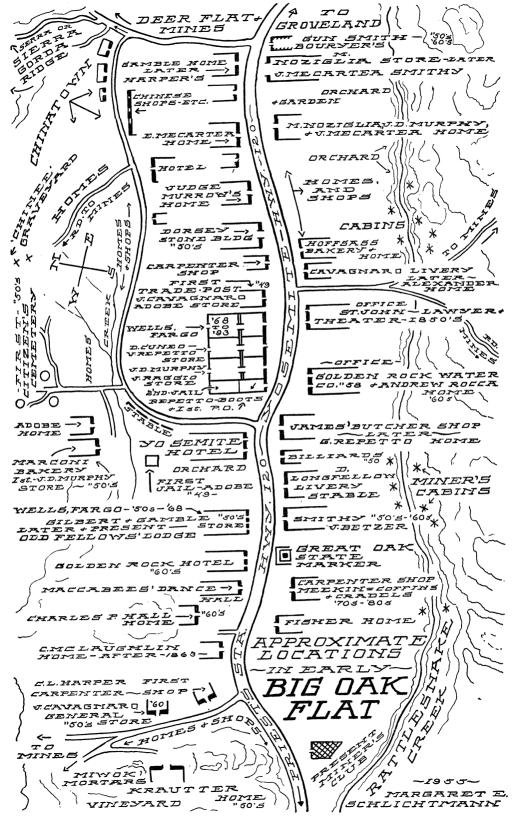

A trading post appeared at once. Rufus Keys inaugurated the first mail delivery, bringing it from Chinese Camp by pack animal.6 (;io Batta Repetto came soon after and settled down as a maker of fine boots. In 1852 one of the finest and largest stone store buildings in the whole Mother Lode country was erected by the roadside. Lodges and a fire department appeared. The Yo Semite House took care of travelers. Various types of business were established by persons whose names are almost as well known today as then.

In 1856 the wagon road was extended to Big Oak Flat. And, in the following year, Tom McGee, who operated a liquor store and ran a pack train at irregular intervals, decided to blaze and open the Mono Indian Trail to saddle traffic. He cleared out the hindering growth and blazed trees to identify the route many of which may still be found—notably at Tamarack Flat.

On February 26, 1859, the first real stage came into town from Chinese Camp, solving the problem of transportation7 and about the same time the town decided that it must have more water. All through the diggings the “more water” fever was only slightly less virulent than the gold fever. As the placer mines waned quartz mines were discovered and went into production. The people of the flat were in good fettle if, they told themselves and each other, they could just get water enough; it was essential to any type of mining and Rattlesnake Creek was small, seldom lasting through the summer.

Influential men formed the Golden Rock Water Company8 and issued stock to the amount of $200,000.00 which, in its day, was a large sum but was less than one-third of the cost of other ditches in the mining area. Heedless of the fact that placer mining was literally “all washed up” they rushed the project. The company built a dam on the South Fork of the Tuolumne at Hardin’s Mill and brought the water down from there by ditch and by flume, one section of which stood aloft on giant wooden piers the height of a twenty-story building. The story of the dam and flume will be given in its proper place.9 The water came 38 miles, serving First and Second Garrote on the way, and reached the flat of the big oak on March 29, 1860. Miners and merchants were wildly excited and it was then, in the full pride of achievement, that the town was incorporated and named. Those were peak days. The Golden Rock Ditch was under the management of Otis Perrin, a ’49er.

In order to concentrate the inappropriately dry data on Tuolumne County’s great water project we will give most of it here: The ditch divided on the height just west of First Garrote (Groveland), one branch passing around the south side of Big Oak Flat and proceeding by ditch down Spring Gulch. It crossed Cobb’s Creek and the Coulterville Road by means of flumes and served mines in Mariposa County, the excess water finally finding its way into Moccasin Creek. The other branch passed north of Big Oak Flat and served the quartz mines on the divide between that settlement and Deer Flat, from whence the surplus water was allowed to run into Slate Gulch and from there by flume across Rattlesnake Creek just above Priest’s Station and on toward the south.

The ditch was nine feet across the top, six at the bottom and thirty inches deep. The water was sold by the sluice-head (or fifty miner’s inches) which cost $5.00 a day. A miner’s inch, they tell us, is the amount of water that flows through an orifice one inch square with the water a given depth over the top of the hole, usually four or six inches depending on the rules of the locality.10

Although most of the promoters of the ditch cannot be proved to have made money and some lost a great deal, they were benefactors to the country in general. They prolonged placer mining and made possible the firm establishment of several quartz mines which produced for years, maintaining large payrolls and stimulating business. But, by the ’70s there was a decline in mine production and the owners could no longer afford high prices for water. Costs for upkeep on the ditch and flume were prohibitive and, by the turn of the century, the ditch was as dry as the details of its actually colorful existence.

From ‘59 to ’63 the town boomed. The California Division of Mines states that the immediate vicinity produced in excess of $25,000,000 from its placer mines. It had four hotels and a large brick theater seating 800 people for which the actors came from San Francisco. It was the accepted shopping center for its section of the county. Its many saloons were crowded. Stages ran two or even more wagons to accommodate the passengers. In 1860 Wells, Fargo & Co. served Big Oak Flat and the Garrotes daily; mail, however, came but once a week.11 The men were avid for entertainment. A feeble and dessicated circus appeared but the never-failing source of noisy enjoyment was the “hurdy-gurdy.” Mrs. Whipple-Haslam describes this group as consisting of four girls with a man to manage them and to play the violin. “The girls,” she wrote, “were mostly German and more decent than the dance-hall girls. Instead of drinking strong liquor, they drank something light. This was necessary because every dance brought to the house fifty cents for drinks and fifty cents to the girl. Each and every dance cost the miner one dollar. But dollars were plentiful in those days.” Apparently the “hurdy-gurdy” never stayed long in one place.

Except from pure habit the flood of ’62 could be passed over without mention in the history of Big Oak Flat, but the drought of the following year caused a fire that all but wiped out the settlement. Ellen Harper May of that town recalled the catastrophe: “It was early October and everything was terribly dry. Suddenly the fire started. Water was low and the sparks flew in all directions and started new blazes. About the only buildings that didn’t burn were those built of stone and there were hardly any trees left. All of Chinatown burned. It was on the north side of the road. The entire business section was wiped out with the exception of the big stone building and the fireproof store of Gilbert and Gamble in which Wells, Fargo had its office. The Odd Fellows’ Lodge burned; the Yo Semite House, owned by Mr. James Kenny, was destroyed at a loss of $5000. The loss of Mr. Longfellow’s livery stable and hay amounted to $ 800. Jacob Betzer realized a loss of $ 5000 when his saloon, house and blacksmith shop were destroyed. The total loss to the community was $48,900, a terrific amount in those days. Columbia, Chinese Camp and Coulterville each had a fire in the year we had ours. ’63 was one of the driest years in the history of the state. Fires were a terrible hazard before we learned to build of stone and adobe. How our hearts did beat whenever we smelled smoke! We were living in First Garrote at that time. Every wagon was filled with men and boys to help fight the fire. Many of my father’s friends were burned out. Shortly after he built a home for us in Big Oak Flat and planted young cedar trees all around. It still stands close to the road at the edge of the town.”

This volume is indebted beyond measure to the patience and goodwill of the older citizens of the Road who have answered questions without number, dozens more than could be entered here for lack of space but which have found their way to historical libraries and will never be lost. Of these friends Ellen Harper May, interviewed almost twenty years ago, was the oldest.

The Yo Semite House had been the best stopping place but its owner immediately built another which he called the Kenny Hotel. In 1872 another Yosemite Hotel was in existence in the town— Proprietor Thomas R. Barnes. Ellen Harper May had memories of James Kenny’s second hotel also and of her girlhood in the Flat. “When I was very young,” she said, “I was employed as a maid in the Kenny Hotel. It was a two-story affair and John Wootton owned a saloon in the same building. I had to work hard but they were good to me. While I was there I met Charles Harper. He was well educated and could quote Shakespeare lengthily. He was shocked when he first came to the diggings with its swearing and drunkeness. He arrived on Sunday and the town was celebrating the day with cock fighting and horse racing. Those painted women he didn’t like at all. He was also shocked at the gambling but he soon got on to some of the ways of the other miners although he always remained a gentleman. He bought a horse before long and raced him on Mr. Robert Simmons’ ranch in Deer Flat. But he never raced on Sunday. It wasn’t long, though, before his jockey was killed in a race and, after that, he wasn’t so interested in the sport.

“Well, we were married. Charles was a fine carpenter and specialized in big barns. He put up many of them here and in Deer Flat. He built the covered bridge at Moccasin. But, more than anything else, he loved the theater. He named one son, Edwin, for Edwin Forrest the great tragedian. When any of the towns showed advertising pictures of the plays in San Francisco he would ride a horse to Stockton and from there he’d take a boat just to see a play. Especially if Lotta Crabtree or Mr. Booth were there.”

When one thinks of what that journey by horse and boat entailed it is doubtful if Lotta Crabtree and Mr. Booth ever received a more sincere compliment.

John Wootton, earlyday citizen, was born in England but was in Australia at the time of the California gold strike. He, with his wife and small son took a sailing vessel for San Francisco some time in May, 1848. There were other young people aboard similarly bound and they were aghast when much of their household goods was thrown overboard to lighten the ship during a storm. Then the little boy contracted measles and was buried at sea. After they reached port a daughter, Louisa, was born but the young mother died. It is almost frightening when one thinks how much stark living is contained in three or four sentences.

John Wootton took his baby girl and started for the diggings. By some chance he settled at the top of Moccasin Hill, building a small shack there in 1855, the same year that the Kirkwoods arrived. Later he settled in Big Oak Flat and eventually bought Kenny’s Hotel.

The Cavagnaro family were well known throughout the Southern Mines and in Yosemite. Their first store in Big Oak Flat was at the west end of town close to Harper’s first carpenter shop. In the ’70s John Cavagnaro kept a general merchandise store in what had been the original adobe trading post. He maintained a livery stable across the road.

James Mecartea moved his family from Chinese Camp to Big Oak Flat in 1872 buying a pretty frame house, already old, which had belonged to the merchant Michael Noziglia. Next to the house but separated by an ancient grape arbor was a stone building which the latter had used as a general store and which Mecartea converted into a smithy by adding a layer of earth on the roof as a precaution against fire. In spite of this forethought the building was gutted many years later, laying bare a neat hole under the cellar steps which had been the hiding place of Mr. Noziglia’s gold dust.

In considering the two men last named it seems a good time to say that we disclaim all responsibility for the spelling of the proper names so well known in the Southern Mines. Members of the same family often had varying ideas and even individuals refused to be coerced and, from time to time, used a bewildering assortment of spellings. Where we have found a signature on a legal document we have adopted it as probably correct and, to save confusion, have used it to designate all members of that family.

To the eleven Mecartea children who had arrived in Chinese Camp were added two more, born in the new home. The last child before they moved was Austin. The first after coming to Big Oak Flat was Eugene. These two brothers became landmarks in the town and never left it. At some time Mecartea ran a smithy farther west down the main street on a lot just east of what is called “the big stone building,” but the exact date is not known.

Blacksmith shops were lively places. James Mecartea was far too busy making picks at one dollar apiece and ox shoes, six for seventy-five cents, to think of gold dust except as a means of exchange. So it happened that the ground under his smithy was never panned. When his numerous children asked for spending money it was his custom to suggest that they take a pan and shovel and repair to the cellar which, on several notable occasions, they actually did. During this decade it was usual to be paid for blacksmith work in produce as money was scarce. The Golden Rock Water Company paid in cash and was considered a very special customer.

In January, 1864, this exciting item appeared in a Sonora paper: “Greenbacks—Greenbacks. Bendix Danielson and Oliver Moore, his partner, have this day paid me their store bill of $140 in Greenbacks at par. (Signed) Alex Kirkwood, Big Oak Flat, Dec. 29, 1864.”12

Indian women were hired to help Elvira Smith Mecartea with the enormous washings and heavy cleaning, but just to bake bread for so many was a chore almost inconceivable today. A housewife of that generation earned her passage through the world. All clothes for women and some for boys were generally made at home; but, in respect to the sewing problem, Mrs. Mecartea was lucky. Only one of her thirteen children was a girl—Alice, a blonde and notably pretty.

At the age of seventy-five James Mecartea contracted pneumonia and quit work and this life at the same time. His son Austin took over and kept up the business until automobiles replaced the horse-drawn vehicles, when he locked the heavy iron doors of his shop with the five-inch key and retired into the old family home. Like many another mountain bachelor he used only the kitchen, a bedroom and side porch. Most of the cupboards had not been opened for so many years that they had lost the knack and Austin had long since forgotten what was in them. In the garden the figs still bore, the roses bloomed spicily and the grape arbor increased to tremendous size. Eugene lived just across the street. On the edge of his front porch stood a rain barrel where dozens of song birds drank while a neighbor’s cat with sleepy eyes but switching tail sat nearby and schemed. The brothers spent hours together on one porch or the other and, on many unhurried occasions, told us of their happy childhood, of how the thirteen young Mecarteas worked, played, studied, got sick and got well again. “We didn’t have many doctors and they lived a long way off,” said Austin reminiscently. “There was a Dr. Williamson in early days when the mines were good but in my time Dr. Lampson of Chinese Camp would have to ride up here in a great emergency. But the women folks could handle most kinds of sickness. Our mother could anyway.”

Across from the smithy lives another pair of brothers, Edwin and Charles Harper, sons of Ellen Harper May and her first husband, Charles L. Harper. To them, also, we were indebted for much of the information contained in this exposition of life as it used to be along the Big Oak Flat Road.

They have told us of the big oak—early symbol of the community. Accounts of its size vary. Those who paced around the spreading roots gave sixteen feet as its diameter. Elbridge Locke of Knight’s Ferry, who was given to understatement, tallied eleven feet, one inch in his diary.

Accounts also vary as to the reason for its untimely demise. It was protected by a town ordinance but the fire of ’63 stripped it to its great charred trunk. Through many interviews we have learned that, previous to that event, greedy miners had worked all one dark night removing the earth from around the roots and taking it away to be panned in private and that it died as a result. If the angry men of the settlement could have found out who did it blood might have been shed, so the secret was well guarded. William Brewer visited the town on June 10, 1863, some four months before the conflagration. He wrote in his personal journal: “The ‘Big Oak’ that gave name to the place [is] nearly undermined, a grand old tree, over 28 ft circum, but now dilapidated although once protected, Town ordinance.” In ’69 the top fell off and left just the lower trunk. Finally that fell and lay on the ground for over thirty years, so bulky that a tall man on horseback could not see over it. Then in 1900 a camper on a cold night accidentally set fire to it. The fire got away from him and he decided that he had better leave. The townspeople were angry all over again, for even as a fallen monarch the big oak was impressive and it was peculiarly their mascot.

The highway, crooked as it is, was the original Big Oak Flat Road and has always been the main street of the town. The miners dug under it too, in their frantic search for dust and nuggets, and the heavy freight wagons sometimes broke through the crust into holes.

In the ’50s the settlement had a schoolhouse about half a mile east of the small group of stores but it was soon abandoned and the children walked to First Garrote (Groveland) for their schooling. In 1860 Mount Carmel Church was erected on a knoll immediately beyond the town.

Robert Curtin assures us that a telegraph line was installed from Big Oak Flat to Yosemite as early as 1866 and that it used a special type of insulator some of which are still in existence. Within his memory there was an old sign on the east end of the Oddfellows’ Building which read “American District Telegraph Company” and he believes that this indicated the company in question. There is also evidence that, in June, 1871, a telegraph office was established in the Savory Hotel at Groveland. Apparently there was not enough business transacted on this short line to insure its success and, in 1875, Harlow Street of Sonora installed a telegraph from that town to Yosemite, via Big Oak Flat, which functioned well.

Wells, Fargo & Co., rated, of course, as one of the town’s important institutions, and we know that, in 1868, William Urich, Wells, Fargo & Company’s agent, used one of the largest pair of gold scales in the Mother Lode country. In the earliest mining days when gold scales had not yet arrived, the amount of gold particles, or “dust,” that could be held between the thumb and forefinger was generally considered a dollar’s worth. The buyer held up his poke of gold dust and the seller took the pinch. Whatever spilled on the counter was supposed also to belong to the seller and at first blankets were often spread and, after a period of time, burned to recover the gold. Various ingenious expedients were utilized. A ’49er wrote: “There was at that time no means of weighing the gold dust; there were no scales to be had; until finally we got a thimble. It w - - - - [would] just hold $ 4. worth of gold dust.”13

A block north of Main Street was the ordinary goldcamp Chinatown. It was not especially large nor outstanding but it maintained its own cemetery and the odd funeral ceremony is remembered by some of the older citizens. Food, especially a fine roasted pig, was taken to the grave and after the service the porker was carried back to the home where everyone had a feast. The other food was usually left at the cemetery.

We asked Mr. Saul Morris of Chinese Camp for a description of a typical Chinese funeral and received his reply: “I attended the funeral of Kwong Wo, Sr. He was probably the first Chinese child born in Tuolumne County and possibly in the state. He was born in 1851 in Chinese Camp where his father conducted a store. Kwong succeeded to his father’s business. Thirty years later he purchased a store in Sonora’s Chinatown. He was a prominent officer in the local Chinese Masonic Order and was held in high esteem by people of all races. Every American attending the funeral was given a ten cent piece and some incense for good luck. Boys old enough to know better would line up in the procession, get their ten cents, then crawl through the fence and get at the end of the procession again and receive another dime. Some of them got thirty cents before they were caught. Bodies did not rest many years in this country. Periodically the remains were exhumed and sent back to China to remain forever among their ancestors.”

Mr. Edwin Harper, born in Big Oak Flat in the late ’70s, told us more about this custom: “I remember,” he said, “when a boy, that a group of us used to watch a certain Chinaman when he came here from San Francisco. He was a priest or some important official. We would hide in the bushes to watch the priest with several others as they walked slowly, in single file, to the graveyard. They wore fine Chinese clothing and hung bright-colored banners on the shrubs around the grave they had come to open. Then they chanted and gestured for a time. The officials brought Chinese laborers to do the actual digging but they were most particular to see that every tiny bone was gathered. A piece of silk was spread at one side of the grave and the bones placed on that. When every single one was found and accounted for they were placed in a small wooden box which was given to the Chinese priest with a good deal of ceremony and they all went back to Chinatown.” Mrs. Stratton of Chinese Camp added the information that the box was always the length of the human thigh-bone; that the contents were scraped clean and that the cue was carefully placed on top just before the box was sealed. Mr. Harper continued, “I was too young to have seen Chinese funerals. They took place during early mining days. But I well remember that at Chinese New Year they all gathered at the cemetery with bowls of cooked rice and little roasted pigs which they put on the graves. On some of the graves where they thought it would be appreciated they added a container of Chinese gin. Then they had a ceremony and went home. They left the rice and the gin but they always took the roast pork along and had a grand feast in their cabins. Then they gambled for the rest of the holiday.” Only the bones of the men were disinterred. Where the women were buried was immaterial.

Big Oak Flat depended on mines and miners. Its prosperity and lack of prosperity ran the usual gamut. Placer mining lasted longer than in other places because the level land was many feet thick with gold bearing gravel, but in the ’60s the rockers, cradles and sluice boxes disappeared and the quartz mines took over. The Mack Mine, owned at one time by the storekeeper of ’49, Albert Mack, and later by James Kenny and Otis Perrin, the Tip Top Mine owned by Jules McCauley, the Lumsden, the Butler (later the Longfellow), the Nonpareil, the Rattlesnake Mill, the Jackson Mill, the Burns, the Cross, the Mohrman, the Mississippi and others kept the town going. They operated intermittently, their pounding stamp mills only noticed when they ceased to thunder. Possibly one would stop production because of the increasing depth of its gold bearing vein, only to be placed again on a profitable basis by more modern machinery and wiped out, after an interval, by advanced costs of operation. Gold discoveries in Alaska and elsewhere rendered Tuolumne’s gold mines of less importance. About 1909 there was a revival due to greatly improved deep shaft methods, but in the 1920’s inflation reduced the condition of the mining towns to a long and dismal slump. This was broken during the depression of the 1930s by a busy scattering of lone operators along the creeks, glad to have the dollar or two that they might accidentally pan out. Then, quite suddenly, the price of gold (which had been as low as $14.00 per ounce in 1849) was raised from $20.67 to $35.00 per fine ounce. This put many districts back into production. In 1940 mines were active and the town was prosperous until 1942 when war mandates practically ended the saga of gold in the Southern Mines.

Now, as far as Big Oak Flat is concerned, but few profitable veins are being worked.

The decline of the quartz mines had a corresponding effect on the towns. As the payrolls fell off the smaller business men left the vicinity; fewer hotels and livery stables were needed; there was less travel on the stage lines and many went out of operation. There was little outlook for the future and the young people left taking with them the life of the settlements, the dances, theatrical performances and band concerts. The Chinese, who are canny business people, left too. Only those remained whose roots had sunk too deeply for removal.

The last half century has been drab along the Mother Lode in comparison with its golden beginnings; but with the coming of year-around play lands in the Sierra Nevada, the building of wide and safe mountain highways and the almost universal possession of a family automobile everything is changed. Give an old-time mining community an interesting history, some authentic ruins and a clean restaurant and the American public will be sure to come sooner or later and to leave good money behind.

* * *

To the left as one enters Big Oak Flat is the site of the early Indian village which the miners under Rufus Keys rudely displaced. A few yards to the north a large mortar rock with several holes for the grinding of acorns may still be seen. Some years later Mr. Krautter, fresh from Germany, built a beautiful one-story home close to the mortars and sent for his daughter Emilie to keep house for him. Immediately to the rear of the home, Krautter constructed rock retaining walls that separated his large vineyard on the knoll from his lower gardens and found time between his sausage and wine making to assist his countryman Ferdinand Stachler in the building of a brewery a few miles east of Big Oak Flat.

It is hard to remember that this was once a lovely flat; the sharp declivity toward Rattlesnake Creek came as a result of surface gold mining operations.

On the north side of the highway, and atop a scenic elevation, is the home of Charles P. Hall, once manager of the Tip Top Mine and son of Capt. Perry W. Hall, one of the founders of the Odd Fellows’ Lodge and a prominent pioneer. Charles Hall married Alice Mecartea. Farther along on the south side and almost hidden in trees is the home of Eunice Watson Fisher, at this time the oldest resident. The large Maccabees’ Dance Hall at one time stood opposite. Near her house, and also on the south side, is the marker commemorating the Big Oak. The lower part of the monument is recessed and grated heavily with iron bars behind which large chunks of the great white oak were placed by the older citizens who had watched with regret the various accidents and acts of vandalism; saving at last a few pieces for memory’s sake.

The Golden Rock Hotel stood, in 1860, opposite the oak and probably was burned along with it in ’63.

The Odd Fellows’ Hall stands alone. Its two neat stories are a study in contrast. The lower floor was built in the early ’50s of dressed schist slabs set in lime mortar. Schist was plentiful but lime was scarce and expensive, having to be freighted in from a quarry near Sonora. It has, however, proved its worth, for many of the buildings which have weathered the years in the Southern Mines are of that construction. The five iron doors that space the front wall are set in perfectly squared frames by the use of bricks which were far too costly to be used for the complete building if suitable rock could be obtained. At first it had but one story and the pitched roof was of cedar shakes. The second story, reached by a covered outdoor stairway, is of sheet metal and was added much later.

The building was used as a grocery by Gilbert and Gamble14 before it survived the fire of 1863. It was then purchased by the Oddfellows who had lost their meeting place and were assisted by other lodges. Yosemite Lodge, No. 97, was instituted in 1860 and is still in active service in the same building.

Nearly opposite the Oddfellows’ Building was the smithy operated by G. Betzer in the ’50s and ’60s.

The “big stone building,” the town’s most impressive landmark, was one of the largest stone structures in the Mother Lode country. According to Mr. H. A. Cobden, its erection was commenced in 1850 or ’51, but he states that some of the rear masonry shows crude Indian labor and that he has evidence that this earlier portion was used as a summer trading post by the Hudson’s Bay Company long before the Gold Rush.

Within the building a stone partition divides it in the middle lengthwise while two other crosswise partitions divide the space in thirds, so that three stores face the street and a corresponding number of rear rooms or offices face the back. An iron door led from each front room to its companion in the rear, helping immensely in fire protection. At first it was known as “the Company’s store” and one could walk from one third to the next and then the next through arches. These were closed later, causing it to be treated as if it were three separate buildings. It was completed in 1852 and had a wooden roof over the front porch which did not survive the fires of its first 75 years. A replacement of corrugated iron blew off in a windstorm and now the narrow porch gets along without a roof. Back of the ponderous iron doors are more conventional inner doors with glass panels. Tree of heaven shades them delicately.

We have been informed by two long-time residents, Clotilda Repetto De Paoli and Edwin Harper, that the suite on the left was first occupied by J. D. Murphy and Luigi Marconi who ran a general merchandise store. Later it came into the hands of Joseph Raggio who did a wide-spread business in surprisingly choice foodstuffs and liquors. The Raggio family were prominent pioneers who also had mining interests.

On the west (or left) end of the building and toward the rear, built as a separate compartment out of rock and adobe, was the room utilized as a jail after the first one was abandoned. It has been a storeroom for many years but the tiny barred windows may still be noted. The Repetto family quote their father as saying that the first jail was of adobe and was across the small side road, west of the big building and somewhat north of the highway.

The small inclosure covered with corrugated metal and just in front of the second jail is an adobe building fully as old as the big stone building, say the old-timers, and possibly older. It was the place of business of Repetto and Chase—makers of boots and shoes that they sold at a uniform price of $20.00 with a guarantee of a year. We have also been told that this little building housed the first post office and that, in 1852, Joseph W. Britton was the postmaster.

The center suite of two rooms seems to have been first occupied by Dominic Cuneo. Afterward it became the Noziglia store for a period and, at different times, was rented to a Mr. Cody and to a Colonel Roote who ran a drug store. When Mr. Cuneo died the three children of Gio Batta Repetto inherited the suite under his will. It was then listed under the name Victor J. Repetto and the Post Office of the 1900s was maintained in the Repetto store.

The right hand suite contained the offices of Wells, Fargo & Co. Sometimes the post office turned up even here and, in 1868, toward the end of a period of prosperity, William Urich was both agent for the express company and postmaster. Court was held in this office. We have some inconclusive evidence that Judge McGehee (or Magee) presided about 1870, with Judge John Gamble and Judge Fred Murrow (known as the marrying judge) following in less than ten years. Wells, Fargo & Co. closed its office and left the town in 1893.

This information takes a little fine dovetailing but, if all the data could be found and compared, is probably quite correct.

The Raggio store was the last to do business in the big stone building. Joseph Raggio had married Emanuella, sometimes called Amelia, the widow of Mr. Marconi who was the baker of the settlement. He produced hot and fragrant bread in an adobe building with iron doors and large ovens of rock and adobe. It stood between the back of the stone building and the town’s first cemetery. The bakery and a nearby small adobe dwelling faced the back road which led to Deer Flat and the rear section of the Yo Semite House. In that period of prosperity between the coming of the ditch water and the devastating fire, families drove many miles to buy Marconi’s tempting pasteries. After the death of Joseph, Amelia Marconi Raggio lived alone in the big building for a time but it was eventually closed by the grandchildren.

Across the highway from the big stone building was the office of the Golden Rock Water Company and the home of its one-time owner, Andrew Rocca, who sold out in 1875 and left Big Oak Flat still a wealthy man. Across the side road from the stone building was the well-known Kenny Hotel. Both the office structure and the Kenny Hotel are completely effaced. But south of the highway still stands the home of Gio Batta Repetto.

It is a neat residence with a picket fence to ward traffic away from the low porch. A hill drops away sharply so that the house is an extra story high in the back. This was not the case in early days when the town was on a true flat. A heavy stone wall under the front of the house prevents the foundations from slipping in wet weather. It was built before 1852 and was there to greet Mr. Repetto (fresh from Italy, speaking five languages and greatly disturbed by Vigilante rule in San Francisco) when he retreated into the simpler living conditions of the mountains. At that time the house had iron hooks in the fireplace for cooking purposes and was occupied by the butcher shop of the James Brothers. Mr. Repetto later bought it and it has been the family home ever since the early ’70s. It is now occupied by his two daughters, Sylvia Vail and Clotilda De Paoli.

Mrs. De Paoli remembers “the Citizens’ Cemetery,” when it had many wooden markers, especially over the graves of children, but fire has gradually wiped them out. It is the oldest burial place of the town. The marble monument marks the resting place of Johannah, wife of August Voight, who was placed here in 1856 when her little daughter Josephine was but two years old—a tragedy all too common in the gold camps. Josephine, later Mrs. Von Off en, may have been the first white child born in the Flat. She never forgot her mother’s grave which originally was outlined according to custom with large chunks of white quartz and had a wooden marker. She had it inclosed with an iron fence, placed the stone headpiece and now lies there herself in the town where she was born.

Above the Citizens’ Cemetery was the burial place of the Chinese. The removal of their bodies to China was a definite obligation on the survivors and there used to be shallow depressions where the soil of the graves had settled after the bodies were taken away. Mining operations in the 1930s effaced these evidences.

The modern post office was built on the site of the original two-roomed stone and adobe trading post which was later occupied by John Cavagnaro’s store.

Beyond the early trading post stood the stone building of Caleb Dorsey and it was there that Charles Harper maintained his second carpenter shop. In later years, so Mrs. De Paoli told us, it was acquired by Judge Redmond and held the Justice Court. After the town was surveyed, about 1879, property deeds were given out signed by J. D. Redmond, County Judge.

Fig and pear trees and a tremendous grapevine mark the site of the Mecartea home. Next to it the blacksmith shop still stands flush with the road. In the ’60s and ’70s there was a tiny building on the east side of the smithy with only a three-foot alley separating the two. In it William Bouryer ran a gun-smithy. When he died it was added to the Mecartea property. Just across the highway is the Harper house, residence of Charles and Edwin Harper and once the home of John Gamble and family.

Mount Carmel, atop a knoll of gleaming white quartz and surrounded by its pioneer graves, is the last point of interest.

Next: Ranches and Rancheria • Contents • Previous: Jacksonville

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/big_oak_flat_road/big_oak_flat.html