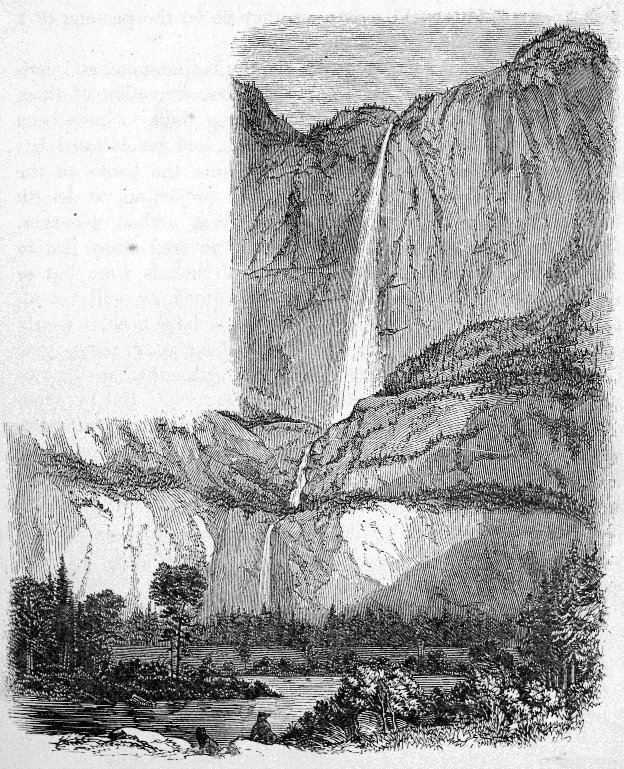

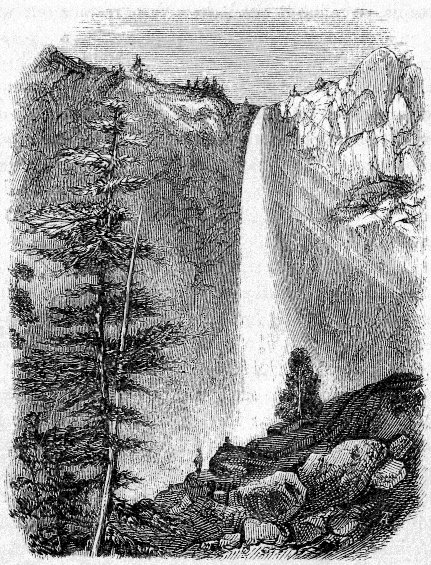

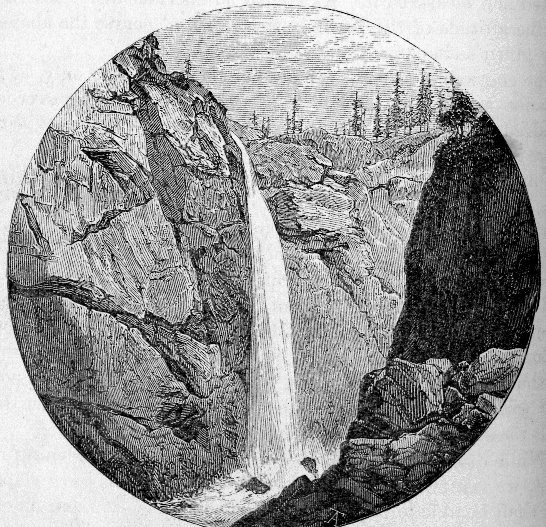

THE YO-SEMITE WATERFALL, TWO THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED AND FIFTY FEET IN HEIGHT.

Photograph by C. L. Weed.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Scenes of Wonder & Curiosity > The Yo-Semite Valley >

Next: Mariposa and Frezno Mammoth Trees • Contents • Previous: Calaveras Natural Bridges

THE YO-SEMITE WATERFALL, TWO THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED AND FIFTY FEET IN HEIGHT. Photograph by C. L. Weed. |

|

“Where rose the mountains, there to him were friends;

Childe Harold. |

|

“If thou art worn and hard beset

Longfellow. |

The reader knows as well as we do, that, although it may be of but little consequence in point of fact, whether a spirit of romance, the love of the grand and beautiful in scenery, the suggestions or promptings of a fascinating woman—be she friend, sweet-heart, or wife—the desire for change, the want of recreation, or the necessity of a restoration and recuperation of an overtasked physical or mental organization, or both—whatever may be the agent that first gives birth to the wish for, or the love of travel; when the mind is thoroughly made up, and the committee of ways and means reports itself financially prepared to undertake the pleasurable task—in order to enjoy it with luxurious zest, we must resolve upon four things: first, to leave the “peck of troubles,” and a few thrown in, entirely behind; second, to have none but good, suitable, and genial-hearted companions; third, a sufficient supply of personal patience, good humor, forbearance, and creators comforts for all emergencies; and, fourth, not to be in a hurry. To these, both one and all, who have ever visited the Yo-Semite Valley, we know will say—Amen.

As there are but few countries that possess more of the beautiful and wildly picturesque than California, it seems to us a sin to neglect to cultivate the knowledge and inspiration of it. Especially as her towering and pine-covered mountains; her wide-spread valleys, carpeted with flowers; her leapiug waterfalls; her foaming cataracts; her rushing rivers; her placid lakes; her ever green and densely timbered forests; her gently rolling hills covered with blooming shrubs and trees, and wild flowers, give a voiceless invitation to the traveller to look upon her and admire.

Whether one sits with religious veneration at the foot of Mount Shasta, or cools himself in the refreshing shade of the natural caves and bridges, or walks beneath the giant shadows of the mammoth trees, or stands in awe looking upon the frowning and pine-covered heights of the Yo-Semite Valley, he feels that

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever,”

and that the Californian’s home will compare, in picturesque magnificence, with that of any other land.

In later years, other employments and enjoyments have been entertained as worthy the attention of the residents and visitors of this coast, than money-making. Now, there are many who throng the highway of elevating and refining pleasure, in spring and summer, to feast the eye and mind upon the beautiful. In the hope, though humbly, of fostering this feeling, we continue our sketches of the most remarkable and interesting, among which doubtless stands the great Yo-Semite Valley.

The early California resident will remember, that during the spring and summer of 1850, much dissatisfaction existed among the white settlers and miners on the Merced, San Joaquin, Chowchilla, and Frezno Rivers and their tributaries, on account of the frequent robberies committed upon them by the Chook-chan-cie, Po-to-en-cie, Noot-cho, Po-ho-ne-chee, Ho-na-chee, Chow-chilla, and other Indian tribes on the head waters of those streams. The frequent repetition of their predatory forays having been attended with complete success, without any attempted punishment on the part of the whites, the Indians began seriously to contemplate the practicability of driving out every white intruder upon their hunting and fishing grounds.

At this time, James D. Savage had two stores, or trading-posts, nearly in the centre of the affected tribes; the one on Little Mariposa Creek, about twenty miles south of the town of Mariposa, and near the old stone fort; all the other on Frezno River, about two miles above where John Hunt’s store now is. Around these stores those Indians who were most friendly, used to congregate; from them and his two Indian wives, Eekino and Homut, Savage ascertained the state of thought and feeling among them.

In order to avert such a calamity, and without even hinting at his motive, he invited an Indian chief, who possessed much influence with the Chow-chillas and Chook-chan-cies, named Josť Jerez, to accompany him and his two squaws to San Francisco; hoping thereby to impress him with the wonders, numbers, and power of the whites, and through him the various tribes who were malcontent. To this Jerez gladly assented, and they arrived in San Francisco in time to witness the first celebration of the admission of California into the Union, on the 29th of October, 1850,* [* The news of the admission, by Congress of California into the Union, on the 9th of September, 1850, was brought by the mail steamer “Oregon,” which arrived in the Bay of San Francisco on the 18th of October, 1850, when preparations were immediately commenced for a general jubilee throughout the State on the 29th of that month. ] and they put up at the Revere House, then standing on Montgomery street.

During their stay in San Francisco, and while Savage was purchasing goods for his stores in the mountains, Josť Jerez, the Indian chief, became intoxicated, and returned to the hotel about the same time as Savage, in a state of boisterous and quarrelsome excitement. In order to prevent his making a disturbance, Savage shut him up in his room, and there endeavored to soothe him, and restrain his violence by kindly words; but this he resented, and became not only troublesome, but very insulting; when, after patiently bearing it as long as he possibly could, at a time of great provocation, unhappily be was tempted to strike Jerez, and followed it up with a severe scolding. This very much exasperated the Indian, and he indulged in numerous muttered threats of what he would do when he went back among his own people. But, when sober, be concealed his angry resentment, and, Indian-like, sullenly awaited big opportunity for revenge. Simple, and apparently small as was this circumstance, like many others equally insignificant, it led to very unfortunate results; for no sooner had he returned to big own people, than he summoned a council of the chief men of all the surrounding tribes; and front his influence and representations mainly, steps were then and there taken to drive out or kill all the whites, and appropriate all the horses, mules, oxen, and provisions they could find.* [* These facts were communicated to us by Mr. J. M. Cunningham (now in the Yo-Semite valley), who was then engaged as clerk for Savage, and was present during the altercation between him and the Indian. ]

Accordingly, early one morning in the ensuing month of November, the Indians entered Savage’s store on the Frezno, in their usual manner, as though on a trading expedition, when an immediate and apparently preconcerted plan of attack was made with hatchets, crow-bars, and arrows; first upon Mr. Greeley, who had charge of the store, and then upon three other white men named Canada, Stiffner, and Brown, who were present. This was made so unexpectedly as to exclude time or opportunity for defence, and all were killed except Brown, whose life was saved by an Indian named “Polonio” (thus christened by the whites), jumping between him and the attacking party, at the risk of his own personal safety, thus affording Brown a chance of escape, which he made the best of, by running all the way to Quartzburg, at the height of his speed.

Simultaneously with this attack on the Frezno, Savage’s other store and residence on the Mariposa was attacked, during his absence, by another band, and his Indian wives carried off. Similar onslaughts having been made at different points on the Merced, San Joaquin, Frezno, and Chow-chilla rivers, Savage concluded that a general Indian war was about opening, and immediately commenced raising a volunteer battalion. At the same time a requisition for men, arms, ammunition, and general stores, was made upon the Governor of the State (General John McDougal), which was promptly responded to by him, and hostilities were at once begun.

Doctor L. H. Bunnell, an eye-witness, belonging to the Mariposa Battalion, has kindly favored as with the following interesting account of this campaign:

“Preparations were being made for defence, when the news came of the sack of Savage’s place on the Frezno, and of two men killed, and one wounded; and close on this report came another, of the murder of four men at Doctor Thomas Payne’s place, at the Four Creeks; one of the bodies being found skinned. The bearer of the news was one who had escaped the murderous assault of the Indians by the fleetness of his horse, but with the loss of an arm, which was amputated, soon after this event, by Doctor Leach, of the Frezno.

“These occurrences so exasperated the people, that a company was at once raised and despatched to chastise the Indians. They found and attacked a large rancheria, high up on the Frezno. During the fight, Lieutenant Stein was killed, and William Little severely wounded. It is not known how many Indians were killed, but the whites assert that in that battle they did nothing to immortalize themselves as Indian fighters. Most of the party were very much dissatisfied with the result of the fight; and while some left for the settlements, others continued in search of the Indians.

“In a few days it was ascertained that some four or five hundred Indians had assembled on a round mountain, lying between the north branches of the San Joaquin, and that they invited attack. They were discovered late in the afternoon; but Captain Boling and Lieutenant Chandler were disposed to have a ‘brush’ with them that evening, if for no other reason than to study their position. Their object was gained, and the captain, with his company, was followed by the Indians on his return from reconnoitring, and annoyed during the night.

“In the morning volunteers were called for, to attack the rancheria. Thirty-six offered, and at daylight the storming commenced with such fury as is seldom witnessed in Indian warfare. The rancheria was fired in several places at the same time, in accordance with a previous understanding, and as the Indians sallied from their burning wigwams, they were shot down, killed, or wounded. A panic seized many of them, and notwithstanding the fear in which their chief, ‘Josť,’ was held, at such a time his authority was powerless to compel his men to stand before the flames, and the exasperated fury of the whites. Josť was mortally wounded, and twenty-three of his men were killed upon the ground. Only one of Captain Boling’s party (a negro who fought valiantly) was touched, and he but slightly. It is not my purpose to eulogize any one, but it is right to say, that that battle checked the Indians in their career of murder and robbery, and did more to save the blood of the whites, as well as of Indians, than any or all other circumstances combined.

“In a subsequent expedition into that region after the organization of the battalion, which was in January, 1851, the remains of Josť were found still burning among the coals of the funeral pyre. The Indians fled at the approach of the volunteers, not even firing a gun or winging an arrow, in defence of their once loved, but dreaded chief.

“It will not, I think, be out of place in this connection, to repeat a speech delivered by Captain Boling on the eve of the expected battle. The captain’s object was to exhort the men to do their duty. He commenced:— ‘Gentlemen— hem— fellow citizens— hem— soldiers— hem— fellow volunteers— hem’— (tremblingly)— and after a long pause, he broke out into a laugh, and said: ‘Boys, I will only say in conclusion, that I hope I will fight better than I speak.’

“It was during the occurrence of the events that have been mentioned above, that the existence of an Indian stronghold was brought to light. When the Indians were told that they would all be killed, if they did not make peace, they would laugh in derision, and say that they had many places to flee to, where the whites could not follow them; and one place they had, which, if whites were to enter, they would be corralled like mules or horses. After a series of perplexing delays, Major Savage, Captain Boling, and Captain Dill, with two companies of the battalion, started in search of the Indians and their Gibraltar. On the south fork of the Merced, a rancheria was taken without firing a gun; the orders from the Commissioners being in ‘no case to shed blood unnecessarily;’ and to the credit of our race, it was strictly obeyed throughout the campaign, except in one individual instance.

“As soon as the prisoners had arrived at the rendezvous designated, near what is now called Bishop’s Camp, Pou-watch-ie and Cow-chit-ty (brothers), chiefs of the tribes we had taken, despatched runners to the chief of the tribe living in the then unknown valley, with criers from Major Savage for him to bring in his tribe to head-quarters, or to the rendezvous.

“Next morning the chief spoken of, Ten-ie-ya, came in alone, and stated that his people would be in during the following day, and that they now desired peace. The time passed for their arrival. After waiting another day, and no certainty of their coming manifested, early on the following morning volunteers were called for to storm their stronghold.

“The place where the Indians were supposed to be living, was depicted in no very favorable terms; but so anxious had the men become, that more offered than were desired by Captain Boling for the expedition. To decide who should go, the captain paced off one hundred yards, and told the volunteers that he wanted men fleet of foot, and with powers of endurance, and their fitness could be demonstrated by a race. By this means he selected, without offence, the men he desired. Some, in their anxiety to go, ran bare-footed in the snow.

“All being ready, Ten-ie-ya took the lead as guide, very much against his inclination; and we commenced our march to the then unknown and unnamed valley. Savage said he had been there, but not by the route that we were taking. About half way, to the valley, which proved about fifteen miles from the rendezvous, on the south fork, seventy-two Indians, women, and children, were met coming in as promised by Ten-ie-ya.

“They gave as an excuse for their delay the great depth of the snow, which in places was over eight feet deep. Ten-ie-ya tried to convince Major Savage that there were no more Indians in the valley, but the whole command cried out as with one voice, ‘Let’s go on.’ The major was willing to indulge the men in their desire to learn the truth of the exaggerated reports the Indians had given of the country, and we moved on. Ten-ie-ya was allowed to return with his people to the rendezvous, sending in his stead a young Indian as guide.

“Upon the arrival of the party in the valley, the young Indian manifested a great deal of uneasiness; he said it would be impossible to cross the river that night, and was not certain that it could be crossed in the morning. It was evident that he had some object in view; but the volunteers were obliged to content themselves for the night, resolved to be up and looking out for themselves early in the morning, for a crossing, or way over the rocks and through the jungle into which they lead been led. Daylight appeared, and with it was found a ford. And such a ford! It furnished in copious abundance, water for more than one plunge bath, and that, too, to some who were no admirers of hydropathy; or, judging from their appearance, had never realized any of its bounties.

“In passing up the valley on the north side, it was soon very evident that some of the wigwams had been occupied the night before; and hence the anxiety of the young Indian, lest the occupants should be surprised. The valley was secured in all directions, but not an Indian could be found. At length, hid among the rocks, the writer discovered an old woman; so old, that when Ten-ie-ya was interrogated in regard to her age, he with a smile, said, that ‘when she was a child, the mountains were hills.’ The old creature was provided with fire and food, and allowed to remain.

“It having snowed during the night, and continuing to snow in the morning, the major ordered the return of the command, lest it should be hemmed in by snow. This was in March, 1851. Ten-ie-ya and others of his tribe asserted most positively that we were the first white men ever in the valley. The writer asked Major Savage, ‘Have you not been in the valley before?’ he answered, ‘No, never; I have been mistaken; it was in a valley below this (since known as Cascade Valley), two and a half miles below the Yo-Semite.’

“On our return to the rendezvous where the prisoners had been assembled, we started for the Commissioners’ camp on the Frezno. On our way in, about a hundred more Indians gave themselves up to Captain Dill’s company. When within about fifteen miles of the Commissioners’ camp, nine men only being left in charge, owing to an absolute want of provisions, the Indians fled—frightened, as it afterward appeared, by the stories told them by the Chow-chillas. Only one of their number was left; be had eaten venison with such a relish at the camp-fire of the whites as to unfit him for active duties; and on his awaking and finding himself alone among the whites, he thought his doom sealed. He was told that he had nothing to fear, and soon became reconciled.

“Upon the arrival, at the Commissioners’ camp, of Captain Boling and his nine men, Von-ches ter(!), a chief, was despatched to find and bring in the frightened Indians. In a few days he succeeded in bringing in about a hundred; but Ten-ie-ya with his people said be would not return.

“After a trip to the San Joaquin, which before has been alluded to, it was resolved to make another trip to the Yo-Semite Valley, there establish head-quarters, and remain until we had thoroughly learned the country, and taken, or driven out, every Indian in it. On our arrival in the valley, a short distance above the prominent bluff known as El Capitan, or as the Indians call it, Tu-toch-ah-nu-lah, which signifies in their language, The Captain, five Indians were seen and heard on the opposite side of the river, taunting us. They evidently thought we could not cross, as the river was so very high (this was in the early part of May), but they were mistaken, as six of us plunged our animals in the stream, swam across, and drove the Indians in among the rocks which obstruct the passage of animals on the north side of the valley; Captain Boling in the mean time crossing above the rocks, succeeded in

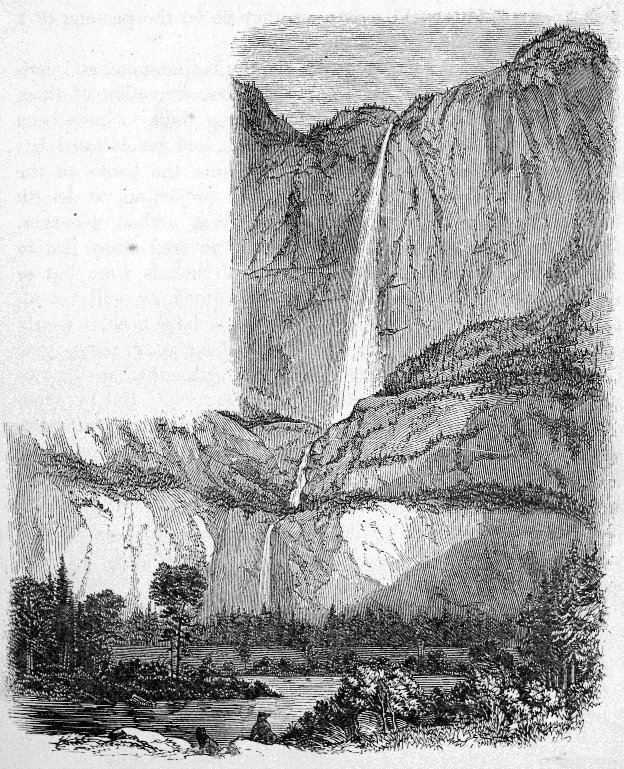

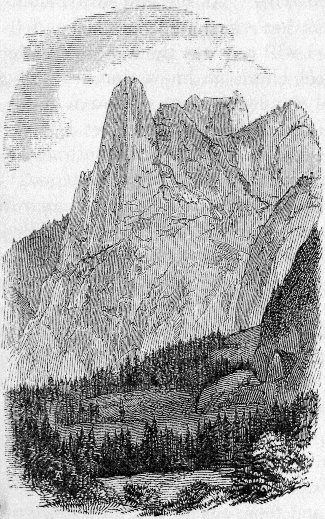

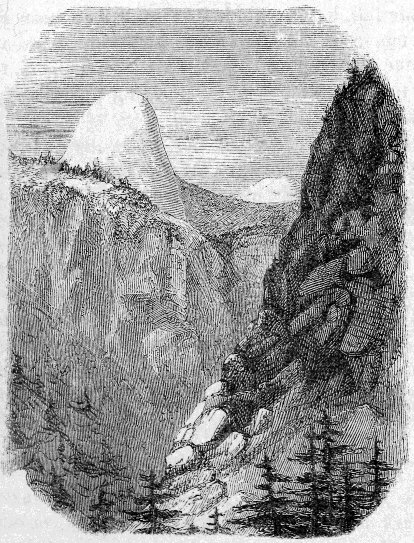

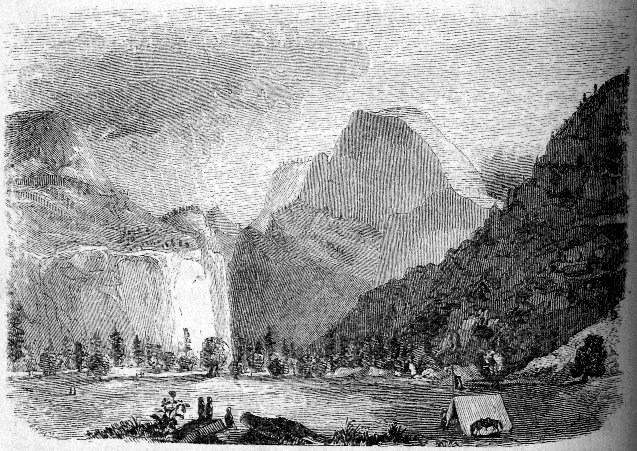

TU-TOCH-AH-NU-LAH, THREE THOUSAND AND EIGHTY-FOUR FEET ABOVE THE VALLEY. From a Photograph by C. L. Weed. |

“The writer was despatched by Captain Boling to guard them against the fire of any scouting party they might encounter in the valley, and succeeded in saving them from an exasperated individual who was met returning with C. H. Spencer, Esq. (now of Chicago), who had been wounded while tracing out the hiding-places of the Indians. When the two sent for Ten-ie-ya left, they said he would be in by ten o’clock the next morning, and that he would not have ran away but for the stories told by the Chow-chillas. On the morning of the day Ten-ie-ya was expected, one of the three Indians escaped, having deceived the guard.

“Soon after, the two remaining were discovered untying themselves. Two men, instead of informing Captain Boling, that he might make more secure their fastenings, placed themselves near their arms to watch their movements, in order, if possible, to distinguish themselves. One was gratified; for as soon as the Indians bounded to their feet, freed from their fetters, they started to run; Ten-ie-ya’s youngest son was shot dead—the other escaped.

“While this was occurring, a party was reconnoitring the scene of Spencer’s disaster, and while there, discovered Ten-ie-ya perched upon a rock overlooking the valley. He was engaged in conversation, while a party cut off his retreat and secured him as a prisoner. Upon his entrance into the camp of the volunteers, the first object that met his gaze was the dead body of his son. Not a word did he speak, but the workings of his soul were frightfully manifested in the deep and silent gloom that overspread his countenance. For a time he was left to himself; but after a while Captain Boling explained to him the occurrence, and expressed his regrets that it should have so happened, and ordered a change of camp, to enable the friends of the dead boy to go unmolested and remove the body.

“After remaining inactive a day or two, hoping that the Indians might come in, a ‘scout’ was made in the direction of the Tuolumne. Only one Indian was seen, and be evidently had been detailed to watch our movements. Various scouts being made to little purpose, it was concluded to go as far up the river as possible, or as far as the Indians could be traced.

“The command felt more confidence in this expedition, from the fact that Cow-chit-ty had arrived with a few of the tribe mentioned before as having been taken on. the south fork of the Merced. They knew the country well, and although their language differed a little train that of the Yo-Semite tribe, yet, by means of a mission Indian, who spoke Spanish and the various Indian tongues of this region, Ten-ie-ya was told if he called in his people they were confident that we would not hurt them. Apparently he was satisfied, and promised to bring them in, and at night, when they were supposed to hover around our camp, he would call upon them to come in; but no Indians came.

“While waiting here for provisions, the chief became tired of his food, said it was the season for grass and clover, and that it was tantalizing for him to be in sight of such abundance, and not be permitted to taste it. It was interpreted to Captain Boling, when he good humoredly said that he should have a ton if he desired it. Mr. Cameron (now of Los Angeles) attached a rope to the old man’s body, and led him out to graze! A wonderful improvement took place in his condition, and in a few days be looked like a new man.

“With returning health and strength came the desire for liberty, and it was manifested one evening, when Mr. Cameron was off his guard, by his endeavor to escape. Mr. Cameron, however, caught him at the water’s edge, as he was about to swim the river. Then, in the fury inspired by his failure to escape, he cried: ‘Kill me if you like; but if you do, my voice shall be heard at night, calling upon my people to revenge me, in louder tones than you have ever made it ring.’ (It was the custom of Captain Boling to ask him to call for his people.)

Soon after this occurrence, it being manifest to all that the old man had no intention of calling in his people, and the provisions arriving, we commenced our march to the head waters of the Py-we-ah, or branch of the Merced, in the valley on which is situated Mirror Lake, and fifteen miles above the valley lake Ten-ie-ya. At a rancheria on the shore of this lake, we found thirty-five Indians, whom we took prisoners. With this expedition Captain Boling took Ten-ie-ya, hoping to make him useful as a guide; but if Chow-chit-ty, who discovered the rancheria, had not been with us, we probably would have gone back without seeing an Indian. In taking this rancheria no Indiana were killed, but it was a death-blow to their hopes of holding out longer against the whites, for when asked if they were willing to go in and live peaceably, the chief at the rancheria (Ten-ie-ya was not allowed to speak) stretching his hand out and over the country, exclaimed: ‘Not only willing, but anxious, for where can we go that the Americans do not follow us?’

“It was evident that they had not much expected us to follow them to so retired a place; and surrounded as they were by snow, it was impossible for them to flee, add take with them their women and children.

“One of the children, a boy five or six years old, was discovered naked, climbing up a smooth granite slope that rises from the lake on the north side. At first he was thought to be a coon or a fisher, for it was not thought possible for any human being to climb up such a slope. The mystery was soon solved by an Indian who went out to him, coaxed him down from his perilous position, and brought him into camp. He was a bright boy, and Captain Boling adopted him, calling him Reub, after Lieutenant Reuben Chandler, who was, and is, a great favorite with the volunteers. He was sent to school at Stockton, and made rapid progress. To give him advantages that he could not obtain in Mariposa county at that time, he was placed in charge of Colonel Lane, Captain Boling’s brother-m-law. To illustrate the folly, as a general thing, of attempting to civilize his race, he ran away, taking with him two very valuable horses belonging to his patron.

“We encamped on the aborts of the lake one night. Sleep was prevented by the excessive cold, so in the gray of morning we started with our prisoners on our return to the valley. This was about the 5th of June; we had taken at the lake four of old Ten-ie-ya’s wives and all of his family, except those who had fled to the Mono country, through the pass which we saw while on this expedition; and, being satisfied that all had been done that could be, and not a fresh Indian sign to be seen in the country, we were ordered to the Frezno. The battalion was soon after disbanded, and nothing more was heard of the turbulent Ten-ie-ya and his band of pillager Indians (who had been allowed once more to go back to the valley upon the promise of good behavior), until the report came of their attack upon a party of whites who visited the valley in 1852, from Coarse-Gold Gulch, Frezno county. Two men of the party, Rose and Shurbon, were killed and a man named Tudor wounded.

“In June, Lieutenant Moore, accompanied by one of Major Savage’s men, A. A. Gray, and some other volunteers, visited the valley with a company of United States troops, for the purpose of chastising the murderers. Five of them were found and immediately executed; the wearing apparel of the murdered men being found upon them. This may shock the sensibilities of some, but it is conceded that it was necessary in order to put a quietus upon the murderous propensities of this lawless band, who were outcasts from the various tribes. After the murder, Ten-ie-ya, to escape the wrath he knew awaited him, fled to the Monos, on the eastern side of the Sierra. In the summer of 1853, they returned to the valley.

“As a reward for the hospitality shown them, they stole a lot of horses from the Monos, and ran them into the Yo-Semite. They were allowed to enjoy their plunder but a short time before the Monos came down upon them like a whirlwind. Ten-ie-ya was surprised in his wigwam, and, instead of dying the very poetic death of a broken heart, as was once stated, he died of a broken head, crushed by stones in the hands of an infuriated and wronged Mono chief. In this fight, all of the Yo-Semite tribe, except eight braves and a few old men and women, were killed or taken prisoners (the women only taken as prisoners), and thus, as a tribe, they became extinct.

“It is proper to say, what I have before stated, that the Yo-Semite Indians were a composite race, consisting of the disaffected of the various tribes from the Tuolumne to King’s River, and hence the difficulty in our understanding of the name, Yo-Semite; but that name, upon the writer’s suggestion, was finally approved and applied to the valley, by vote of the volunteers who visited it. Whether it was a compromise among the Indians, as well as with us, it will now be difficult to ascertain. The name is now well established and it is that by which the few remaining Indians below the valley call it.

“Having been in every expedition to the valley made by volunteers, and since that time assisted George H. Peterson (Fremont’s engineer) in his surveys, the writer, at the risk of appealing egotistical, claims that he had superior advantages for obtaining correct information, more especially as, in the first two expeditions, Ten-ie-ya was placed under his especial charge, and he acted as interpreter to Captain Boling.

“It is acknowledged that Ah-wah-ne is the old Indian name for the valley, and that Ah-wah-ne-chee is the name of its original occupants; but as this was discovered by the writer long after he had named the valley, and as it was the wish of every volunteer with whom be conversed that the name Yo-Semite be retained, he said very little about it. He will only say, in conclusion, that the principal facts are before the public, and that it is for them to decide whether they will retain the name Yo-Semite, or have some other.

L. H. Bunnell.

“We, the undersigned, having been members of the same company, and through most of the scenes depicted by Doctor Bunnell, have no hesitation in saying, that the article above is correct.

“James M. Roane,

“Geo. H. Crenshaw.”

We cheerfully give place to the above communication, that the public may learn how and by whom this remarkable valley was first visited and named; and, although we have differed with the writer and others concerning the name given, as explained in several articles that have appeared at different times in the several newspapers of the day, in which Yo-hom-i-te was preferred, yet, as Mr. Bunnell was the first to visit the valley, we most willingly accord to him the right of giving it whatever name be pleases. At the same time, we will here enter the following reasons for calling it Yo-ham-i-te, the name by which we have been accustomed to speak of it.

In the summer of 1855, we engaged Thomas Ayres, a well-known artist of San Francisco (who unfortunately lost his life not long since, by the wreck of the schooner Laura Bevan), to accompany us on a sketching four to the Big Trees and the valley above alluded to.

When we arrived at Mariposa, we found that the existence even of such a valley was almost unknown among a large majority of the people residing there. We made many inquiries respecting it, and how to find our way there; but, although one referred us to another who had been there after Indians in 1851, and he again referred us to some one else, we could not find a single person who could direct us. In this dilemma we met Captain Boling, the gentleman spoken of above, who, although desirous of assisting us, confessed that it was so long since he was there, that he could not give us any satisfactory directions. “But,” said he, “if I were you, I would go down to John Hunt’s store, on the Frezno, and he will provide you with a couple of good Indian guides from the very tribe that occupied that valley.”

We adopted this plan, although it took us twenty-five or thirty miles out of our way; deeming such a step the most prudent under the circumstances. Up to this time we had never heard or known any other name than “Yo-Semite.”

Mr. Hunt very kindly acceded to our request, and gave us two of the most intelligent and trustworthy Indians that he had, and the following day we set out for the valley.

Toward night on the first day, we inquired of Kossum, one of our guides, how far he thought it might possibly be to the Yo-Semite Valley, when he looked at as earnestly, and said: “No Yo-Semite! Yo-Hamite; sabe, Yo-Ham-i-te.?” In this way were we corrected not less than thirty-five or forty times on our way thither, by these Indians. After our return to San Francisco, we made arrangements for publishing a large lithograph of the great falls; but, before attaching the name to the valley and falls for the public eye, we wrote to Mr. Hunt, requesting him to go to the most intelligent of those Indians, and from them ascertain the exact pronunciation of the name given to that valley. After attending to the request, he wrote us that “the correct pronunciation was Yo-Ham-i-te, or Yo-Hem-i-te.” And, while we most willingly acquiesce in the name of Yo-Semite, for the reasons above stated, as neither that nor Yo-Ham-i-te, but Ah-wah-ne, is said to be the pure Indian name, we confess that our preferences still are in favor of the pure Indian being given; but until that is determined upon (which we do not ever expect to see done now), Yo-Semite, we think, has the preference. Had we before known that Doctor Bunnell and his party were the first whites who ever entered the valley (although we have the honor of being the first, in later years, to visit it and call public attention to it), we should long ago have submitted to the name Doctor Bunnell had given it, as the discoverer of the valley.

At the time we visited it there was scarcely the outline of an Indian trail visible, either upon the way or in the valley, as all were overgrown with grass or weeds or covered with old leaves; and nothing could be found there but the bleaching bones of animals that had been slaughtered, and an old acorn post or two, on which a supply of edibles had once been stored by the Indian residents.

Having thus explained the incidents connected with the early history of this remarkable place we invite the courteous reader to give us the pleasure of his company thither.

These routes, like those to the mammoth trees of Calaveras, are very numerous, and consequently cannot be fully described in this work; but the principal ones, and these at present most travelled, are via Stockton and Coulterville, Mariposa, and Big-Oak Flat; Stockton or Sacramento City being the starting-point for persons living adjacent to San Francisco.

The Coulterville stage leaves Stockton at six o’clock A. M. on each alternate day, arriving in Coulterville the same evening about eight or nine o’clock P. M. At twelve o’clock midnight, it departs from Coulterville, and returns to Stockton about three o’clock P. M., in time for the San Francisco boats. Fare to the Crimea House, seven dollars; from the Crimea House, via Don Pedro’s Bar, to Coulterville, four dollars.

The Mariposa stage also leaves Stockton at six o’clock A. M. on alternate days, arriving in Hornitas the same evening, and Mariposa about eleven A. M. the day following; through fare, ten dollars.

The Big-Oak Flat stage, via Sonora or Columbia, leaves Stockton daily at six o’clock A. M., reaching Sonora or Columbia the same evening, and on the following day arrives at its destination, about noon. Fare to Sonora, eight dollars; from Sonora to Big-Oak Flat, three dollars and fifty cents. As we have before remarked, these rates of fare change a little according to the amount of opposition between the different stage companies.

As the route to the valley at present most travelled, probably, is via Stockton and Coulterville—although we do not know why, either of the others being equally agreeable—we shall describe that more fully.

Leaving Stockton, then, we journey over a level and oak-studded plain, to the “Twelve-Mile House,” where we change horses and take breakfast, which generally occupies from ten to twenty minutes. The country then gradually becomes gently rolling, and although covered with wild flowers, is almost barren of trees or shrubs. We again change horses at the Twenty-five Mile House. At noon we reach Knight’s Ferry, where a group of sturdy miners is congregated in front of the hotel, and a bell announces that dinner is ready.

After taking refreshments, with loss of our appetites and forty-five minutes, we not only again change horses, but find ourselves and our baggage changed to another stage—as the newest and best looking ones seemed to be retained for the comparatively level and city end of the route, while the dust-covered and paint-worn are used for the mountains.

At the Crimea House, our “bags and baggage” are again set down, and after a very agreeable delay of one hour—during which time the obliging landlord, Mr. Brown, informs us that errors of route and distance have been made by journalists, who were not familiar with their subject, and by which those persons who in private carriages were liable to go by La Grange, some five miles out of their way—a new line as well as conveyance is taken, known as the “Sonora and Coulterville.”

About six o’clock P. M. we reach Don Pedro’s Bar. But for an unusual number of passengers, we should most likely be subjected to another change of stage: now, fortunately, the old and regular one will not contain us all, so that the only change made is in horses, and after a delay of twelve minutes, we are dashing over the Tuolumne River, across a good bridge.

Now the gently rolling hills begin to give way to tall mountains; and the quiet and even tenor of the landscapes change to the wild and picturesque. Up, up we toil, many of us on foot, as our horses puff and snort like miniature locomotives from hauling but little more than the empty coach. The top gained, our road lies through forests of oak and nut pines, across guts, and down the sides of ravines and gulches, until we reach Maxwell’s Creek; from which point an excellent road is graded on the side of a steep mountain, to Coulterville; and all that we seem to hope for, is that the stage will keep upon it, and not tip over and down into the abyss that is yawning below. Up this mountain we again have to patronize the very independent method of going “afoot;” and while ascending it, our party may probably be startled by a rustling sound from among the bushes below the road, where shadowy human forms can be seen moving slowly toward us. Hearts beat quick, and images of Joaquin and Tom Bell’s gang rise to our active fancies. “They will rob and perhaps murder us,” suggests one. “We can die but once,” retorts another. “Oh, dear! what is going to be the matter?” exclaims a third. Let us all keep close together,” pantomimes a fourth.

“That’s a hard old mountain,” exclaims the ringleader of a party of miners, who are climbing the steep sides of the mountain, with their blankets at their backs, and who have caused us all our alarm, as he and big companions quietly seat themselves by the side of the mad. “Good evening, gentlemen.” “Good evening.” “Why, bless us, these men who have almost frightened us out of our seven senses, are nothing but fellow-travellers!” “Can’t you see that?” now valorously inquires one whose knees had knocked uncontrollably together with fear only a few moments before. At this we all laugh; and the driver having stopped the stage, say, “Get in, gentlemen,” and we have enough to talk and joke about until we reach Coulterville. Here by the kindness of Mr. Coulter (the founder of the town), our much-needed comforts are cared for; and, after making arrangements for an early start the morrow, let us retire for the night, well fatigued with the journey; having been upon the road fifteen hours, perhaps. The following table will probably give an approximating idea of the and distance made between Stockton and Coulterville:

| Time made. | Miles | |

| Left Stockton at a quarter past six A. M. | h. m. | |

| From Stockton to Twelve Mile House | 1.35 | 12 |

| From Stockton to Twenty five Mile House | 4.15 | 23 |

| From Stockton to Twenty five Mile House | 4.35 | 30 |

| From Stockton to Foot Hills | 4.35 | 30 |

| Fro Stockton to Knight’s Ferry | 5.40 | 37 |

| From Stockton to Rock River House including detention for dinner) | 7.40 | 44 |

| From Stockton to Crimea House | 8.40 | 48 |

Here we exchange stages, and delay one hour. |

||

| h. m. | ||

| From Stockton to Don Pedro’s Bar (including delay at Crimea House) | 11.30 | 60 |

| From Stockton to Coulterville (exchange horses, and delayed twelve minutes | 15.30 | 71 |

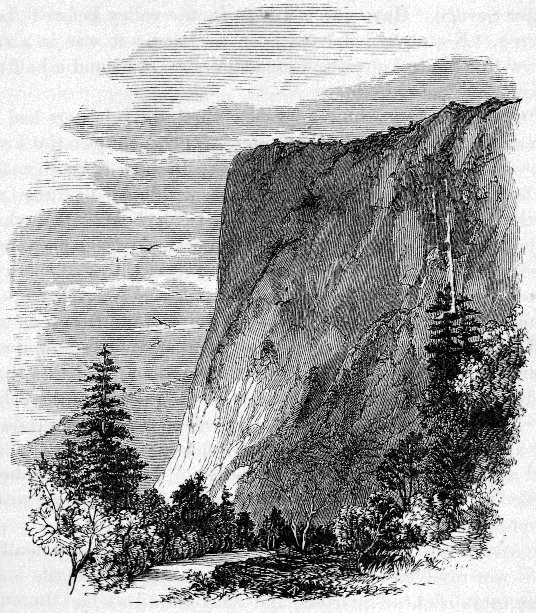

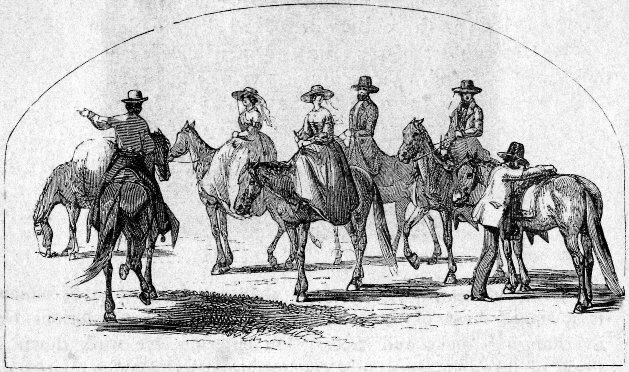

Our first considerations the following morning are for good animals, provisions, cooking utensils, and a guide—the former (all but the good) are probably supplied by a gentleman who in the uncommon and somewhat ancient patronymic of at about twenty-five dollars per head—almost the original cost of each animal, judging from their build and speed—for a trip eight days.

For the supply of provisions and cooking utensils, Mr. Coulter and the guide will relieve us of all anxiety; and at or about a quarter to nine the next morning, we may be in our saddles ready for the start. How we are attired, or armed; what is the impression produced upon the bystanders; or, even, what is our own opinion of our personal appearance, is a matter of indifference, or should be

HO! FOR THE YO-SEMITE VALLEY. |

For the first three or four miles, our road is up a rough, mountainous point, through dense chaparal bushes that are growing on both sides of us, to a high, bold ridge; and from whence we obtain a splendid and comprehensive view of the foot-hills and broad valley of the San Joaquin. At this point we enter a vast forest of pines, cedars, firs, and oaks, and ride leisurely among their deep and refreshing shadows, occasionally passing saw-mills, or ox-teams that are hauling logs or lumber, until, at about half-past one P.M., twelve miles distant from Coulterville, we reach

This is a singular grotto-like formation, about one hundred feet in depth and length, and ninety feet in width, and which is entered by a passage not more than three feet six inches wide, at the northern end of an opening some seventy feet long by thirteen feet wide, nearly covered with running vines and maple trees, that grow out from within the cave. When these are

BOWER CAVE. |

From this point to “Black’s Ranch,” our five miles’ ride is delightfully cool and pleasant, and, for the most part, by gradual ascent up a long gulch, shaded in places with a dense growth of timber, and occasionally across a rocky point to avoid a long detour or difficult passage. This part of our journey will occupy about two hours.

On account of the steep hill-side upon which our trail now lies, and the pious habits of some of our horses, this ride may be attended with some little danger, and requires—in consideration of the value, on such a trip, of a sound neck, if only for the convenience of the thing—that we remember, and practice, too, the Falstaffian motto concerning discretion, and take it leisurely, until we arrive at Deer Flat, six miles above Black’s.

As there may not be the convenience of a hotel at this point, it will be well for us to make the best of camping out, and, after a good hearty meal has been discussed, commence preparations for passing the night, as comfortably as possible, in our star-roofed

CAMPING AT DEER FLAT—NIGHT SCENE. |

“Ere slumber’s spell hath bound us.”

Deer Flat is a beautiful green valley of about fifteen or twenty acres, surrounded by an amphitheatre of pines and oaks, and being well watered, makes a very excellent camping-ground. By the name given to this place, we might think that some game probably will reward an early, morning’s hunt, and accordingly, about daybreak, sally out, prepared for dropping a good fat buck, Rod find that no living thing larger than a dove can be started up.

It is always well, on such trips, to get an early start; for, although not in possession of the brightest of feelings, either mental or physical, we no sooner become fairly upon our way, than the wild and beautiful scenes on every hand make us forget the broken slumbers of the night, and the unsatisfactory breakfast of the morning. As we journey on, we reach Hazel Green in about two hours—six miles distant from Deer Flat.

From this point, the distant landscapes begin to gather in interest and beauty, am we thread our way through the magnificent forest of pines on the top of the ridge. Here, the green valley, deep down on the Merced; them, the snow-clothed Sierra Nevadas, with their rugged peaks towering up; and, in the sheltered hollows of their base, nature’s snow-built reservoirs glitter in the sun. These are glorious sights, amply sufficient in themselves to repay the fatigue and trouble of the journey, without the remaining climax to be reached when we enter the wondrous valley. In about two hours more we reach Crane Flat, six miles from Hazel Green, where, as there is plenty of grass and water, we may as well take lunch, and a good rest.

It will be necessary, here, to remark that this flat is frequently used for camping purposes, for one or more days, to allow of an opportunity of visiting several large trees that are growing a short distance below it. As the reader would, no doubt, like to visit these trees, we will briefly refer to them.

After leaving the flat, a slight detour to the right, of about a mile and a half, will bring us into the vicinity of these trees. They consist of a small cluster growing near the steep side of a deep cañon; and belong to the same class as these found in Calaveras, and other districts. Two of them, which grow from the same root, and unite a few feet above the base, are, on this account, called “The Siamese Twins.” These are about one hundred and fourteen feet in circumference at the ground, and, consequently, about thirty-eight feet in diameter, including both. The bark has been cut on one side of one of these, and found to measure twenty inches in thickness. Near the “Twins,” and interspersed among other trees, are five others of the same kind. Two of these measure about seventy-six feet in circumference. Their average height is about two hundred and fifteen feet; and they are perfectly straight.

The visitor will experience no difficulty in finding this small grove of large trees, on account of the trail to them being well worn. But he will find the journey somewhat laborious, owing to the steepness and length of the descent and ascent.

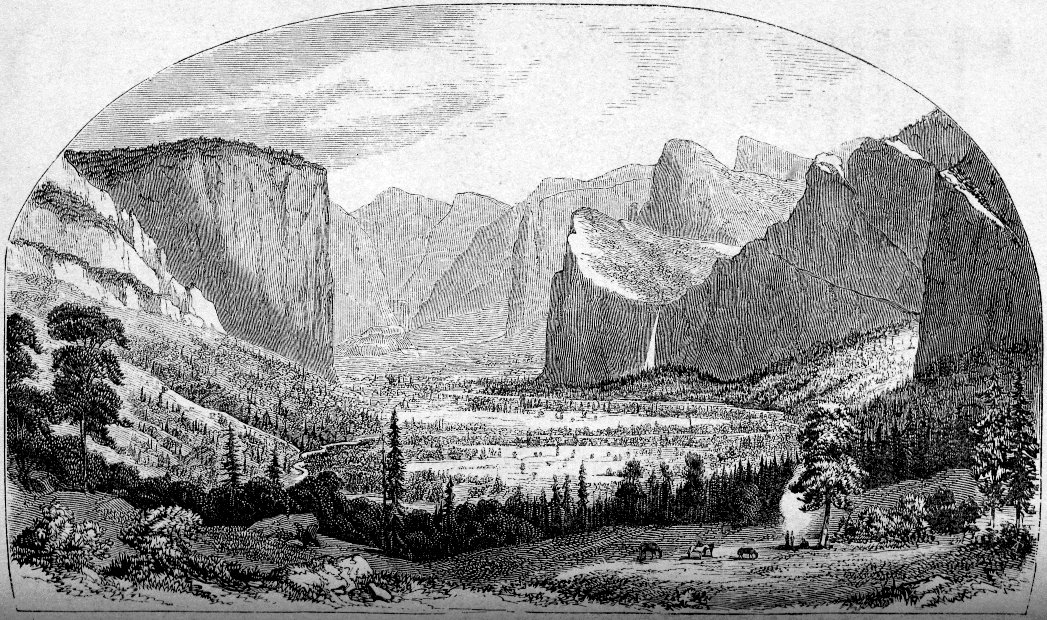

It is difficult to say whether the exciting pleasures of anticipation quicken our pulses to the more vigorous use of our spurs, or that the horses already smell, in imagination at least, the luxuriant patches of grass in the great valley, or that the road is better than it has been before: certain it is, from whatever cause, we travel faster and easier than at any previous time, and come in sight of the haze-draped summits of the mountain-walls that girdle the Yo-Semite Valley, in a couple of hours after leaving Crane Flat—distance, nine miles.

Now, it may so happen that the reader entertains the idea that he can just look upon a wonderful or an impressive scene, and fully and accurately describe it. If so we gratefully tender to him the use of our chair; for we candidly confess that we cannot. The truth is, the first view of this convulsion-rent valley, with its perpendicular mountain cliffs, deep gorges, and awful chasms, spread out before us like a mysterious scroll, takes away the power of thinking, much less of clothing thoughts with suitable language.

The following words from Holy Writ will the better convey the impression, not of the thought, so much, as the profound feeling inspired by that scene:

“And I beheld when he had opened the sixth seal, and lo! there was a great earthquake; and the sun became blank as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became as blood, and the stars, of heaven fell unto the earth, even as a fig-tree casteth her untimely figs, when she is shaken of a mighty wind.

“And the heaven departed as a scroll when it is rolled together, and every mountain and island were moved out of their places.

“And the kings of the earth, and the great men, and the rich men, and the chief captains, and mighty men, and every bondman, and every freeman, hid themselves in the dens and in the rocks of the mountains; and said to the mountains and recital Fall on us, and hide us from the face of Him that sitteth on the throne, and from the wrath of the Lamb; for the great day of His wrath is count, and who shall be able to stand?”

“This verily is the stand-point of silence!” at length escapes in whispering huskiness, from the lips of one of our number. “Let us name this spot The Stand-Point of Silence.” And so let it be written in the note-book of every tourist, as it will be in big inmost soul when be looks at the appalling grandeur of the Yo-Semite Valley from this spot.

We would here suggest, that if my visitor wishes to see this valley in all its awe-inspiring glory, let him go down the outside of the ridge for a quarter of a mile, and then descend the eastern side of it for three or four hundred feet, as from this point a high wall of rock, at your right hand, stands on the opposite side of the river, that adds much to the depth, and, consequently, to the height of the mountains.

When the inexpressible “first impression” has been overcome, and human tongues regain the power of speech, such exclamations as the following may find utterance: “Did mortal eyes ever behold such a scene in any other land?” “The half had not been told us!” ”My heart is full to overflowing with emotion at the sight of so much appalling grandeur in the glorious works of God!” “I am satisfied!” This sight is worth ten years of labor,” etc., etc.

The following anecdote will help to illustrate the gratification of witnessing this sight:

“A young man, named Wadilove, when on his way to the valley, had fallen sick with fever at Coulterville, and who, consequently, had to remain behind his party, became a member of ours; and, on the morning of the second day out, experiencing a relapse, he requested us to leave him behind; but, as we expressed our determination to do nothing of the kind, at great inconvenience to himself, he continued to ride slowly along. When at Hazel Green, be quietly murmured, ‘I would not have started on this trip, and suffer as much as I have done this day, for ten thousand dollars.’ But, when he arrived at this point, and looked upon the glorious wonders presented to his view, he exclaimed: ‘I am a hundred times repaid now for all I have this day suffered, and I won would gladly undergo a thousand times as much, could I endure it, and be able to look upon another such a scene.’”

“Here let me renew my tribute,” says Horace Greeley, “to the marvellous bounty and beauty of the forests of this whole mountain region. The Sierra Nevadas lack the glorious glaciers, the frequent rains, the rich verdure, the abundant cataracts of the Alps; but they far surpass them—they surpass any other mountains I ever saw—in the wealth and grace of their trees. Look down from almost any of their peaks, and your range of vision is filled, bounded, satisfied, by what might be termed a tempest-tossed sea of evergreens, filing every upland valley, covering every hill-side, crowning every peak, but the highest, with their unfading luxuriance. That I saw, during this day’s travel, many hundreds of pines eight feet in diameter, with cedars at least six feet, I am confident; and there were miles of such, and smaller trees of like genus, standing as thick as they could grow. Steep mountain-sides, allowing these giants to grow, rank above rank, without obstructing each other’s sunshine, seem peculiarly favorable to the production of these se[r]viceable giants. But the Summit Meadows are peculiar in their heavy fringe of balsam fir, of all sizes, from those barely one foot high to those hardly less than two hundred, their branches surrounding them in collars, their extremities gracefully bent down by the weight of winter snows, making them here, I am confident, the most beautiful trees on earth. The dry promontories which separate these meadows, are also covered with a species of spruce, which is only less graceful than the firs aforesaid. I never before enjoyed such a tree-feast as on this wearing, difficult ride.”

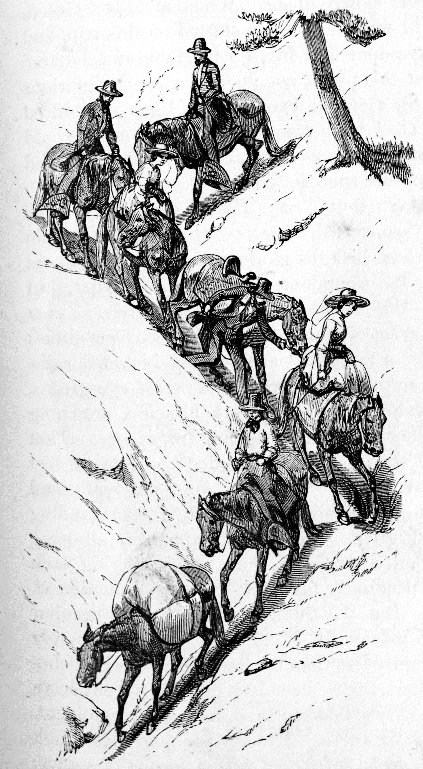

About a mile further on, we reached that point where the

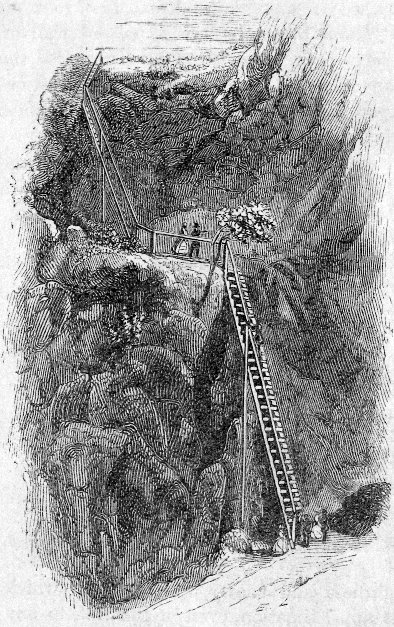

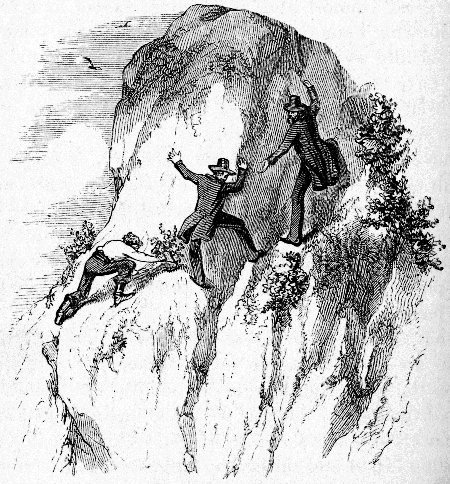

DESCENDING THE MOUNTAIN TO THE YO-SEMITE VALLEY. |

Yet, in some of the steepest places of the trail, one or two of the most timid of the party will be disposed to dismount, and walk, as at some points the descent is certainly very trying to the nerves.

We will here remark that there are but three localities by which this valley can be safely entered—two at the lower or western end, on which the Coulterville and Mariposa trails are laid; and one at the upper or eastern end, by a tributary of the river which makes in from the main ridge of the Sierras, and which is travelled mostly by persons going and returning to and from the Walker’s River mines.

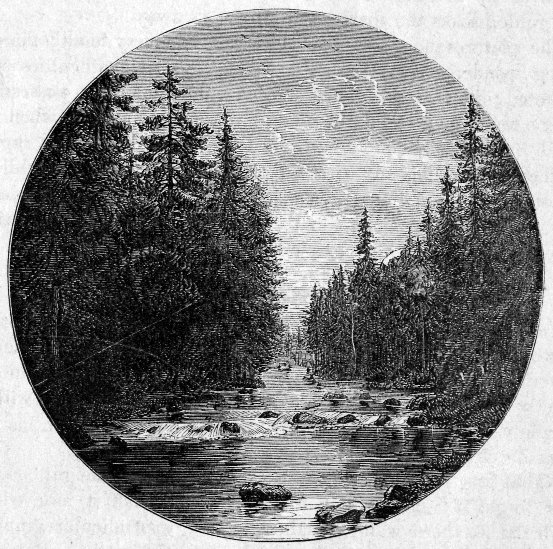

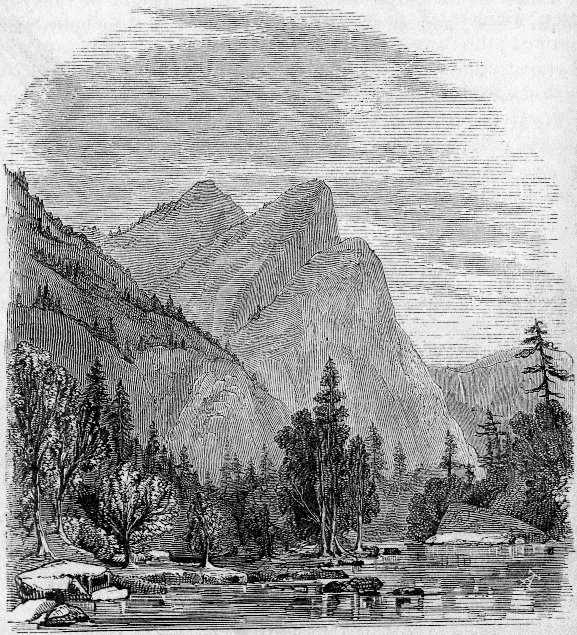

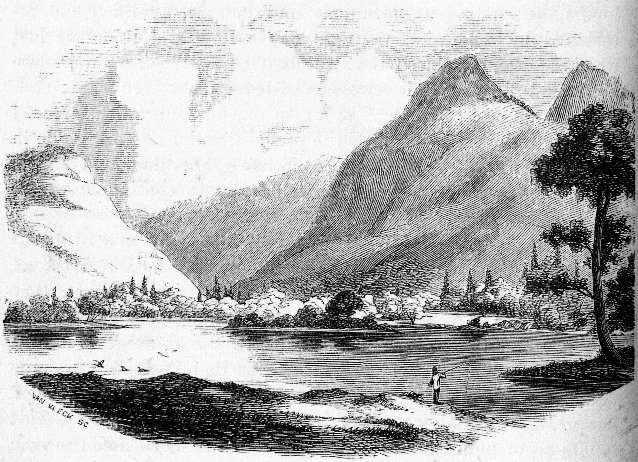

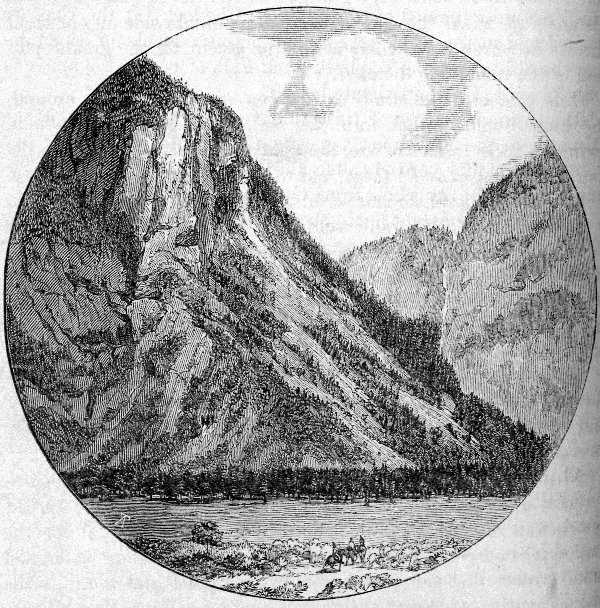

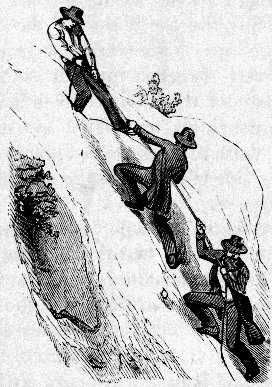

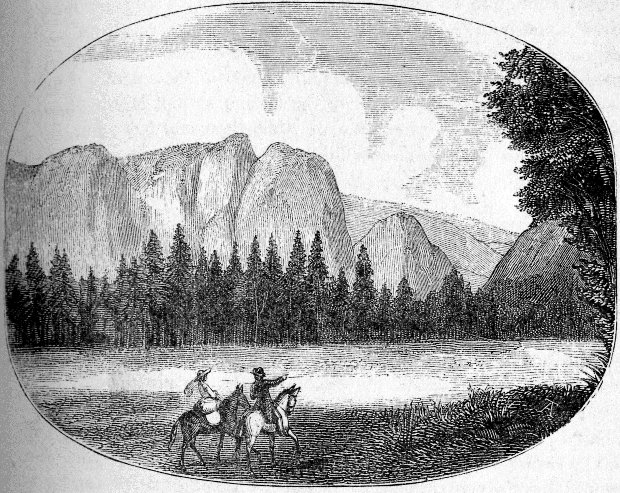

RIVER SCENE IN THE YO-SEMITE VALLEY, NEAR THE FOOT OF THE TRAIL. From a Photograph by C. L. Weed. |

About two miles from the “Stand-Point of Silence,” while descending the mountain, we arrive at a rapid and beautiful cascade, across which is a rude bridge; here we can quench our thirst with its deliciously cool water. It may be well here to mention that there is an ample supply of excellent water, at convenient distances, the entire length of the route, whether by Coulterville, Big-Oak Flat, or Mariposa.

Soon, another cascade is reached and crossed, and its rushing heedlessness of course among rocks, now leaping, over this, and past that; here giving a seething, there a roaring sound; there bubbling and gurgling, and smoking, and frothing, will keep smile of us looking and lingering until another admonition of our guide breaks the charm, and hurries us away.

The picturesque wildness of the scene on every hand; the exciting wonders of so romantic a journey; the difficulties, surmounted; the dangers braved and overcome, puts us in possession of one unanimous feeling of unalloyed delight; so that when we reach the foot of the mountain, and look upon the beautiful rapids of the river rolling and swelling at the side of the trail, white a forest of oaks and pines stands sentinel on its banks, or ride, side by side, among the trees in the valley, we congratulate each other upon looking the very picture of happiness personified.

Fatigued as we may be, every object around us has an interest as we pass this point, or watch that shadow slowly climbing those lowering granite walls, when the last rays of the setting sun are quietly draping the highest peaks of this wonderful valley with a purple veil of hazy ether; as Mr. Greeley expresses it, in his interesting descriptive visit—

“That first full, deliberate gaze up the opposite height! can I ever forget it? The valley is here scarcely half a mile wide, while its northern wall of mainly naked, perpendicular granite, is at least four thousand feet high—probably more. But the modicum of moonlight that fell into this awful gorge [Mr. G. arrived in the night] gave to that precipice a vagueness of outline, an indefinite, vastness, a ghostly and weird spirituality. Had the mountain spoken to me in audible voice, or begins to lean over with the purpose of burying me beneath its crushing mass, I should hardly have been surprised. Its whiteness, thrown into bold relief by, the patches of trees or shrubs which fringed or flocked it wherever a few handfuls of its moss, slowly decomposed to earth, could contrive to hold on, continually suggested the presence of snow, which suggestion, with difficulty refuted, was at once renewed. And, looking up the valley, we saw just such mountain precipices, barely separated by intervening watercourses of inconsiderable depth, and only receding sufficiently to make room for a very narrow meadow inclosing the river, to the furthest limit of vision.”

“ELEACHAS,” OR THE THREE BROTHERS, 3,437 FEET HIGH. From a Photograph by C. L. Weed. |

Our trail, for the most part, lies among giant pines, from two hundred to two hundred and fifty feet in height, and beneath the refreshing shade of outspreading oaks and other tress. Not a sound breaks the expressive stillness that reigns, save the occasional chirping and singing of birds as they fly to their nests, or the low, distant sighing of the breeze in the tops of the forest. Crystal streams occasionally gurgle and ripple across our path, whose sides are fringed with willows and wild flowers that are ever blossoming, and grass that is ever green. On either side of us stands almost perpendicular cliffs, to the height of thirty-five hundred feet; and on whose rugged faces, or in their uneven tops

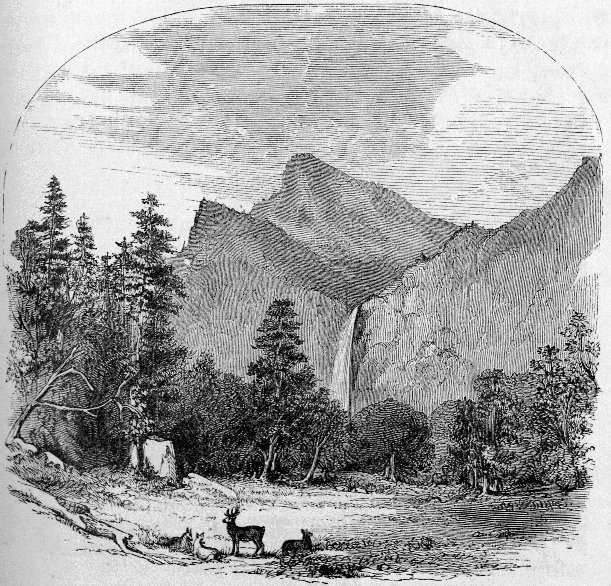

DISTANT VIEW OF THE “POHONO,” OR BRIDAL VEIL WATERFALL. From a Photograph by C. L. Weed. |

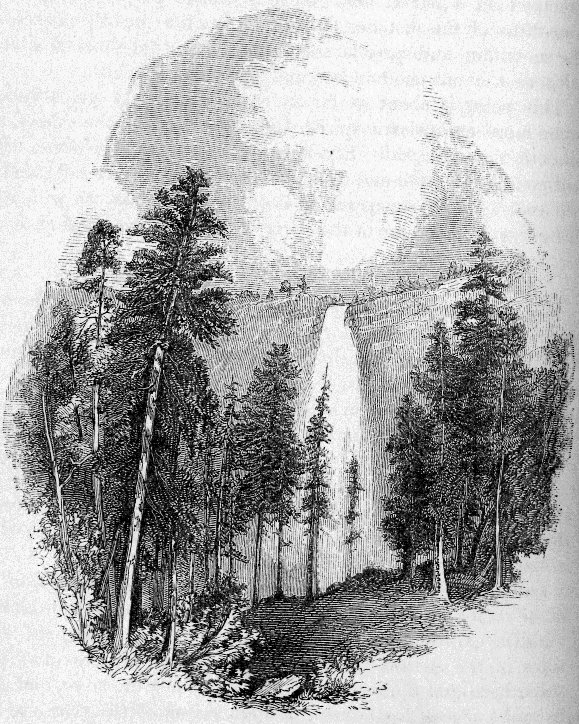

Shortly after passing Tu-toch-ah-nu-lah, on our left, we come in sight of three points which the Indians know as “Eleacha,” named after a plant much used for food, but which some lackadaisical person has given the common-place name of “The Three Brothers!” beyond which we got the first glimpse of the upper part of the Cho-looke (the Indian name), or Yo-Semite Water-Fall.

Perhaps we ought previously to leave mentioned, that the first water-fall of any magnitude which strikes our attention on entering the valley—and, indeed, on several occasions before reaching the bottom land of the valley—is the “Pohono” (Indian

THE FERRY. From a Photograph by C. L. Weed. |

Surrounded by such states of loveliness and sublimity, we feel a reluctance to break the charon they throw upon us by any speech; when some one is almost sure to cry out—“The Ferry.” Here the river is about sixty feet wide, and twelve feet deep— across which we call be speedily conveyed on a good boat, at the rate of thirty-seven and a half cents per head for men, women, and animals.

Below we append a table of distances, and the probable time consumed in making the trip from Coulterville:

| Time of Travel. h. m. | Resting & camping. h. m. | Distance miles. | |

| From Coulterville to Bower Cave. | 4 25 | . . | 12 |

| Rest at the Cave. | . . | 3 00 | . . |

| From the Cave to Black’s Inn. | 2 00 | . . | 5 |

| Rest at Black’s. | . . | 0 40 | . . |

| From Black’s to Deer Flat. | 1 45 | . . | 6 |

| Camp for the night at Deer Flat, from 9 P. M., til 7 A. M. | . . | 11 50 | . . |

| From Deer Flat to Hazel Green. | 2 00 | . . | 6 |

| Rest at Hazel Green. | . . | 0 25 | . . |

| From Hazel Green to Crane Flat. | 1 30 | . . | 6 |

| Rest and lunch at Crane Flat. | . . | 2 00 | . . |

| From Crane Flat to “Stand-Point of Silence”. | 2 10 | . . | 9 |

| Stop at “Stand-Point of Silence”. | . . | 0 45 | . . |

| From “Stand-Point of Silence,” to Second Cascade Bridge. | . . | . . | 2 |

| From Second Cascade to foot of trail into valley. | . . | . . | 5 |

| From foot of trail to Upper Hotel. | . . | . . | 6 |

| From “Stand-Point of Silence,” to Upper Hotel. | 5 15 | . . | . . |

| _____ | _____ | _____ | |

| Total time of travel. | 19 5 | 17 5 | . . |

| Total time of resting and camping. | 17 5 | ||

| Total time from Coulterville to hotel in valley. | 36 10 | ||

| Total distance. | 57 |

About a third of a mile above the ferry, we arrive at Cunningham’s store and boarding-house—where its obliging owner will do all in his power to make us feel at home; who is as well, if not better informed concerning the name and history of every point in this valley than my other man in the country, and to whom we are indebted for much valuable information. Here we get a full and excellent view of Sentinel Rock, on our right, and the Cho-looke, or Yo-Semite Fall, on our left the highest in the valley; but, as by this time it may be getting late, if we wish to go to the Upper or Yo Semite Hotel, half a mile higher up, we must reserve further description for another occasion.

After the fatigue and excitement of the ride, and the novel circumstances and broken slumbers of the past nights, it is natural to suppose that when we reach the valley, and quietly encamp, our rest will be both deep and refreshing; but experience will prove that this supposition is altogether too favorable—for, owing to the musquitos having recently given a series of very successful concerts in the valley, as reported by other travellers, we find that they are now in high spirits, and have a playful habit of alighting on and piercing our noses and foreheads, to keep as awake, that we may not lose a single note of their nocturnal serenade.

Then, weary as we are, it seems such a luxury to lie awake and listen to the splashing, washing, roaring, surging, hissing, seething sound of the great Yo-Semite Falls, just opposite; or to pass quietly out of a sheltering place, and look up between the lofty pines and spreading oaks, to the granite cliffs, that tower up, with such majesty of form and boldness of outline, against the vast etherial vault of heaven; or watch, in the moonlight, the ever-changing shapes and shadows of the water, as it leaps the cloud-draped summit of the mountain, and falls in gusty torrents on the unyielding granite, to be dashed to an infinity of atoms. Then to return to our fern-leaf couch, and dream of some tutelary genius, of immense proportions, extending over us his protecting arms— of his admonishing the water-fall to modulate the music of its voice into some gently soothing lullaby, that we may sleep and be refreshed.

Some time before the sun can get a good, honest look at us, deep down as we am in this awful chasm, we see him painting his rosy smiles upon the ridges, and etching lights and shadows in the furrows of the mountain’s brow, as though he took a pride showing up to the best advantage, the wrinkles time had made upon it; but all of its feel too fatigued fully to enjoy the thrilling grandeur and beauty that surround us.

Here it will not be out of place to remark that ladies or gentlemen —especially the former—who visit this valley to look upon appreciate its wonders, and make it a trip of pleasurable enjoyment, should not attempt its accomplishment in less than three days from Mariposa, Coulterville, or Big-Oak Flat. If this is remembered, the enjoyment of the visit will be more than doubled.

After a substantial breakfast, made palatable by that most excellent of sauces, a good appetite, our guide announces that the horses are ready, and the saddle-bags well stored with such good things as will commend themselves acceptably, to our attention, about noon; and that the first place to visit is the Yo-Semite Fall.

Crossing a rude bridge over file main stream, which is here almost sixty feet in width, and nine in depth, we keep down the northern bank of the river for a short distance, to avoid a large portion of the valley in front of the hotel, that is probably overflowed with water. On either side of our trail, in several places, such is the luxuriant growth of the ferns, that they are above our shoulders as we ride through them.

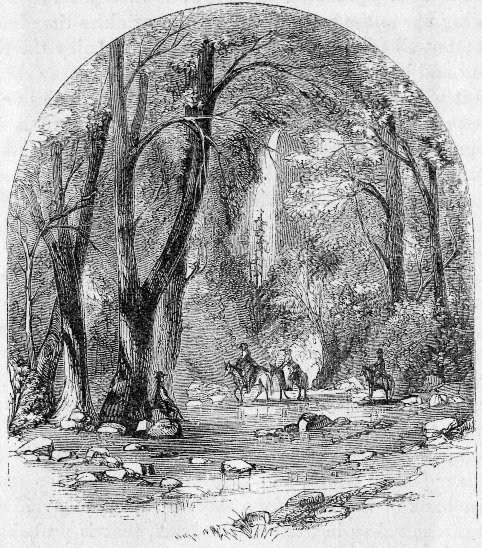

Presently we reach one of the most beautifully picturesque scenes that eye ever saw. It is the ford. The oak, dogwood, maple, cottonwood, and other trees, form an arcade of great beauty over the sparkling, rippling, pebbly stream, and, in the back-ground, the lower fall of the Yo-Semite is dropping its sheet of snowy sheen behind a dark middle distance of pines and hemlocks.

As the snow rapidly melts beneath the fiery strength of a hot summer sun, a large body of water, most probably, is rushing past, forming several. small streams—which, being comparatively shallow, are easily forded. When within about a hundred and fifty yards of the fall, as numerous large boulders begin to intercept

THE FORD OF THE YO-SEMITE. From a Photograph by C. L. Weed. |

Now a change of temperature soon becomes perceptible, as we advance; and the almost oppressive beat of the centre of the valley is gradually changing to that of chilliness. But up, up, we climb, over this rock, and past that: tree, until we reach the foot, or as near as we can advance to it, of the great Yo-Semite Falls when a cold draught of air rushes down upon us from above. about equal in strength to an eight knot freeze; bringing with it a heavy shower of finely comminuted spray, that falls with sufficient force to saturate our clothing in a few Immolate. From

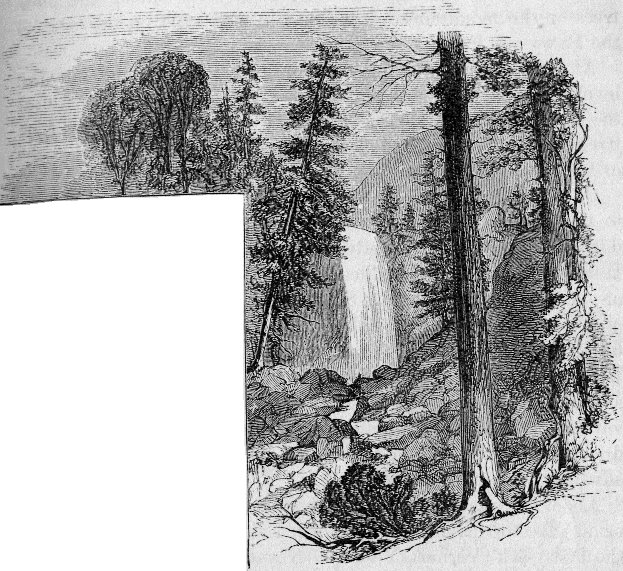

NEAR VIEW OF THE YO-SEMITE FALLS.—2,550 FEET IN HEIGHT. From a Photograph by C. L. Weed. |

Those who have never visited this spot, must not suppose that the cloud-like spray that descends upon us is the main fall itself, broken into infinitesimal particles, and becoming nothing but a sheet of cloud. By no means; for, although this stream shoots over the margin of the mountain, nearly seven hundred feet above, it falls almost in a solid body—not in a continuous stream exactly, but having a close resemblance to an avalanche of snowy rockets that appear to be perpetually trying to overtake each other in their descent, and mingle the one into the other; the whole composing a torrent of indescribable power and beauty.

Huge boulders, and large masses of sharp, angular rocks, are scattered here and there, forming the uneven sides of so immense, and apparently ever-boiling cauldron; around, and in the interstices of which, numerous dwarf ferns, weeds, grasses, and flowers, are ever growing, when not actually washed by the falling stream.

It is beyond the power of language to describe the awe-inspiring majesty of the darkly-frowning and overhanging mountain walls of solid granite that here hem us in on every side, as though they would threaten us with instantaneous destruction, if not total annihilation, did we attempt for a moment to deny their power. If man ever feels his utter insignificance at any time, it is when looking upon such a scene of appalling grandeur as the one here presented.

The point from whence the photograph was taken from which our engraving is made—being almost underneath the fall—might lead to the supposition that the lower section, which embraces more than two-thirds of the picture, was the highest of the two seen; when, in fact, the lower one, according to the measurements of Mr. Denman, superintendent of Public Schools in San Francisco; of Mr. Petersen, the engineer of the Mariposa and Yo-Semite Water Company; and of Mr. Long, county surveyor, is about seven hundred feet above the level of the valley, while the upper fall is about one thousand four hundred and forty-eight feet, and between the two, measuring about four hundred feet, is a series of rapids rather than a fall, giving the total height of the entire series fall at two thousand five hundred and forty-eight feet.

After lingering here for several hours, with inexpressible feelings of suppressed astonishment and delight, qualified and intensified by veneration, we may take a long and reluctant last upward gaze, convinced that we shall “never look upon its like again,” until we pay it another visit at some future time; and, making the best of our way to where our horses are tied, proceed to endorse the truthfulness of the prognostications of our guide in the morning before starting, concerning appetites and lunch. This being despatched, it will be well for us to continue our ride, and pay a

Leaving the Yo-Semite Falls, we recross the ford, and thread our way through the far-stretching vistas of luxuriant green that open before us; the bright sunlight and sombre shadows ever winking and winkling upon the sparkling and gurgling stream and dimly-defined trail; until we emerge on a grassy and flowered covered plateau on the north side of the valley, near the base of the great North Dome, called by the Indians “To-coy-ae.” This mountain of naked granite, with scarcely a tree or shrub growing from a single crevice, towers above you to the height of three thousand seven hundred and twenty-five feet. Its sides are nearly perpendicular for more than two thousand feet, and in which a colossal arch is formed, doubtless from the falling of several sections of the rock, This has been designated the “Royal Arch of To-coy-ae.” This, we believe, has never been measured; but we should judge its altitude, from the valley to the crown of the arch, to be about one thousand seven hundred feet, and its span about two thousand feet; its depth in, from the face of the rock, is about eighty or ninety feet. Them is one additional feature here that should not be overlooked, and that is the small streams of water that leap down over it, like falling strings of pearls and diamonds. These add much, in early spring, to the attractiveness of the scene.

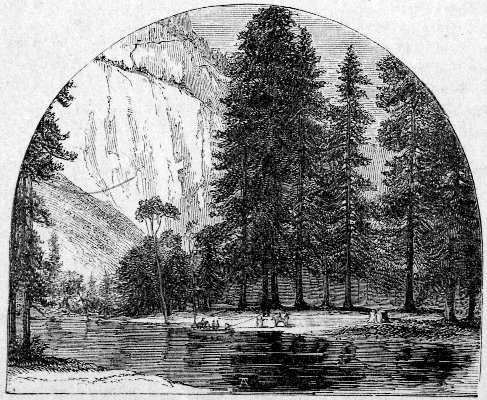

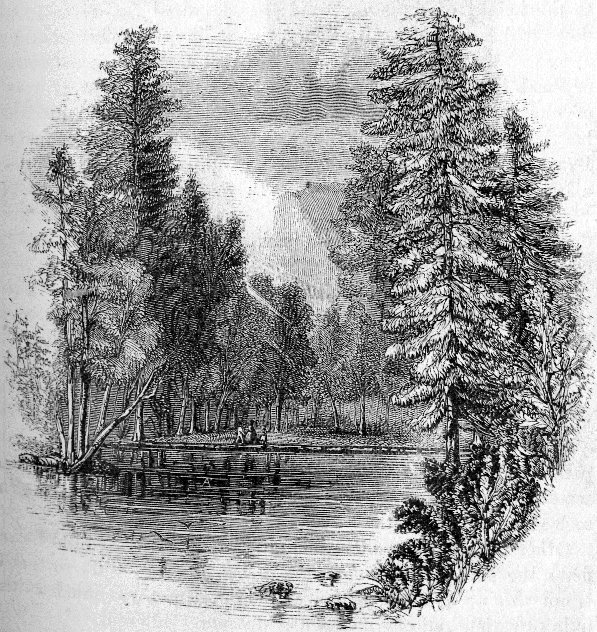

Having crossed the plateau, we ride over some rocky hillocks, and among a park-like array of oak trees, until we arrive at Lake Ah-wi-yah, so named and known by the Indians, but which has

LAKE AH-WI-YAH. |

This lake, although a charming little sheet of crystal water of almost a couple of acres in extent, in which numerous schools of speckled trout may be seen gaily disporting themselves, would be unworthy of a notice, but for the picturesque grandeur of its surroundings. On the north and west lie immense rocks that have become detached from the tops of the mountain above; among these grow a large variety of trees and shrubs, many of which stand on and overhang the margin of the lake, and are reflected on its mirror-like bosom. To the north-east opens a vast gorge or cañ, down which impetuously rush the waters of the fork of the Merced, which debouches into and supplies the lake.

On the south-east stands the majestic Mount Tis-sa-ack, or “South Dome,” four thousand five hundred and ninety-three feet in altitude above the valley. Almost one-half of this immense mass, either from some convulsion of nature, or

“Time’s effacing fingers,”

has fallen over, by which, most probably, the dam for this lake was first formed. Yet proudly, aye, defiantly erect, it still holds its noble head, and is not only the highest of all those around, but is the greatest attraction of the valley. Moreover, in this are centred many agreeable associations to the Indian mind; as here was once the traditionary home of the guardian spirit of the valley, the angel-like and beautiful Ti-sa-ack, after whom her devoted Indian worshippers named this gloriously majestic mountain. While we sit in the shade of these fine old trees, and look upon all the objects around its, mirrored on the unruffled bosom of the lake, let its relate the following interesting legend of Tu-toch-ah-nu-lah, after whom the vast perpendicular and massive projecting rock at the lower end of the valley was named, and with which is interwoven this history of Tis-sa-ack.

This legend was told in an eastern journal, by a gentleman residing here, who signs himself “Iota,” and who received it from the lips of an old Indian; the relation of which, although several of interest are omitted, will, nevertheless, prove very entertaining:

[Editor’s note: this “legend” “was almost certainly fabricated” according to NPS Ethnologist Craig D. Bates. —dea.]

“It was in the unremembered past that the children of the sun first dwelt in Yo-Semite. Then all was happiness; for Tu-toch-ah-nu-lah sat on high in his rocky home, and cared for the people whom he loved. Leaping over the upper plains, he herded the wild deer, that the people might choose the fattest for the feast, He roused the bear from his cavern in the mountain, that the brave might hunt. From his lofty rock he prayed to the Great Spirit, and brought the soft rain upon the corn in the valley. The smoke of his pipe curled into the air, and the golden sun breathed warmly through its blue haze, and ripened the crops, that the women might gather them in. When he laughed, the face of the winding river was rippled with smiles; when he sighed, the wind swept sadly through the singing pines; if he spoke, the sound was like the deep voice of the cataract; and when he smote the far-striding bear, his whoop of triumph rang from crag to gorge—echoed from mountain to mountain. His form was straight like the arrow, and elastic like the bow. His foot was swifter than the red deer, and his eye was strong and bright like the rising sun.

“But one morning, as be roamed, a bright vision came before him, and, then the soft colors of the West were in his lustrous eye. A maiden sat upon the southern granite dome that raises its gray head among the highest peaks. She was not like the dark maidens of the tribe below, for the yellow hair rolled over her dazzling form, as golden waters over silver rocks; her brow beamed with the pale beauty of the moonlight, and her blue eyes were as; the far-off hills before the sun goes down. Her little feet shone like the snow-tufts on the wintry pines, and its arch was like the spring of a bow. Two cloud-like wings wavered upon her dimpled shoulders, and her voice was as the sweet, sad tone of the night-bird of the woods.

“‘Tu-toch-ah-nu-lah,’ she softly whispered; then gliding up the rocky dome, she vanished over its rounded top. Keen was the eye, quick was the ear, swift was the foot of the noble youth as he sped up the rugged path in pursuit; but the soft down from her snowy wings was wafted into his eyes, and he saw her no more.

“Every morning now did the enamored Tu-toch-ah-nu-lah leap the stony barriers, and wander over the mountains, to meet the lovely Tis-sa-ack. Each day he laid sweet acorns and wild flowers upon her dome. His ear caught her footstep, though it was light as the falling leaf; his eye gazed upon her beautiful form, and into her gentle eyes; but never did he speak before her, and never again did her sweet-toned voice fall upon his ear. Thus did he love the fair maid, and so strong was his thought of her that he forgot the crops of Yo-Semite, and they, without rain, wanting his tender care, quickly drooped their heads, and shrunk. The wind whistled mournfully through the wild corn, the wild bee stored no more honey in the hollow tree, for the flowers had lost their freshness, and the green leaves became brown. Tu-toch-ah-nu-lah saw none of this, for his eyes were dazzled by the shining wings of the maiden. But Tis-sa-ack looked with sorrowing eyes over the neglected valley, when early in the morning she stood upon the gray dome of the mountain; so, kneeling on the smooth, hard rock, the maiden besought the Great Spirit to bring again the bright flowers and delicate grasses, green trees, and nodding acorns.

“Then, with an awful sound, the dome of granite opened beneath her feet, and the mountain was riven asunder, while the melting snows from the Nevada gushed through the wonderful gorge. Quickly they formed a lake between the perpendicular walls of the cleft mountain, and sent a sweet murmuring river through the valley. All then was changed. The birds dashed their little bodies into the pretty pools among the grasses, and fluttering out again, sang for delight; the moisture crept silently through the parched soil; the flowers sent up a fragrant incense of thanks; the corn gracefully raised its drooping head; and the sap, with velvet footfall, ran up into the trees, giving life and energy to all. But the maid, for whom the valley had suffered, and through whom it had been again clothed with beauty, had disappeared as strangely as she came. Yet, that all might hold, her memory in their hearts, she left the quiet lake, the winding river, and yonder half-dome, which still bears her name, ‘Tis-sa-ack.’ It is said to be four thousand five hundred feet high, and every evening it catches the last rosy rays that am reflected from the snowy peaks above. As she flew away, small downy feathers were wafted front her wings, and where they fell—on the margin of the lake—you will now see thousands of little white violets.

“When Tu-toch-ah-nu-lah knew that she was gone, he left his rocky castle and wandered away in search of his lost love. But that the Yo-Semites might never forget him, with the hunting-knife in his bold hand, he carved the outlines of his noble head upon the face of the rock that bears his name. And there, they still remain, three thousand feet in the air, guarding the entrance to the beautiful valley which had received his loving care.”

By this time the rapidly declining sun, and an admonishing voice from our organs of digestion, are both persuasive influences to recommend an early departure for the hotel and dinner, and which, we need not add, will be promptly responded to.

As we sit in the stillness and twilight of evening, thinking over and conversing about the wondrous scenes our eyes have looked upon this day; or listen, in silence, to the deep music of the distant waterfalls, our hearts seem full to overflowing with a sense of the grandeur, wildness, beauty, and profoundness to be felt and enjoyed when communing with the glorious works of nature, which call to mind those expressive lines of Moore:

|

“The earth shall be my fragrant shrine;

My temple, Lord! that arch of thine; My censer’s breath, the mountain airs; And silent thoughts, my only prayers.” |

Visitors generally prefer paying a visit to the Pohono Fall, before undertaking those of greater difficulty at the upper end of the valley, that they may become somewhat better rested from the fatigue of the journey. Let us, therefore, not be out of the fashion, but take a quiet ride down the south side of the valley at once; and the first point of striking interest we shall notice on our left will be Sentinel Rock, a lofty and solitary peak, upon which the watch-fires of the Indians have often been lighted to

SENTINEL ROCK, 3,270 FEET HIGH. |

Further on, we see a singular group of peaks, that will resemble almost any thing we can conjure up, according to the time of day we may be passing, as every change in the position of the sun will give a new set of shadows; but that which it most resembles, is the dilapidated front of some grand old cathedral, with towers and buttresses; and, in one place, a circle that a strong imagination can make into a clock, which will indicate the time of day to a moment!

This passed, we come in front of the Pohono Fall. After threading our way among trees and bushes, over rocks and water-courses, it becomes necessary that we should dismount, and tie our animals, as the remaining distance is over a rough ascent of rocks, which will have to be accomplished on foot. As this is short, we shall thread our way among bushes and boulders, without much difficulty, until the heavy spray from the fall saturates our clothing, and the velvety softness of the moist grasses growing upon the little ridge we have climbed, reminds us that the goal of our desire is reached.