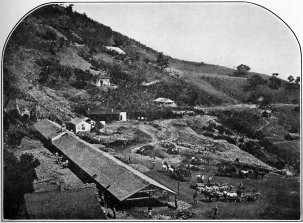

THE PLANILLA

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Up & Down Calif. > 1861 Chapter 1 >

| Next: Chapter 2 • Contents • Previous: Book 1 |

BOOK II

1861

San Juan—A Call to San Francisco—Union Sentiment—Personnel Problems—Hot Weather—Doctor Cooper—San Juan Mission—Monterey Again—Sea Life.

San Francisco.

Sunday, June 23, 1861.

I sent my last a few days ago from San Juan, to go by the steamer of yesterday.1 You are surprised, no doubt, to see my letter dated at San Francisco. But, although I sent Averill up on Monday last, yet Tuesday I received a letter from the Professor asking me to come up here immediately to confer with him on some important business relating to present and future plans of operations. The next morning found me on the stage, and Wednesday night found me here. But I will continue my journal in the order of time. I closed my last letter Sunday or Monday.

On Monday, June 17, I explored alone some high sandstone hills southwest of San Juan—hills covered with wild oats, with here and there bold outcroppings of coarse red sandstone, often worn into fantastic and grotesque forms by the weather. Ledges would be perforated with numerous holes and caverns from the smallest size up to those capable of holding a hundred men. Thousands of swallows had built their nests in them, as they build in barns at home. I sat down in one of these caves, the largest I saw, opening out to the valley and commanding a lovely view. A steep ravine lay below me, brilliant and fragrant with flowers, around which swarms of humming birds were flitting, like large bees. Various species of humming birds are common, but I have nowhere seen so many as at that place. They often came in the cave, hovering in the air near me; several times they would stand in the air so close to me that I could touch them with my hand easily, then they would dart away again.

The aspect of the scenery around San Juan is peculiar—a level valley, enclosed in large fields, hills rising beyond; all covered with oats, now ripe. The hills have a dry, soft, straw-colored look, which, in the twilight, or by moonlight, is peculiarly rich.

On Tuesday I rode a few miles to visit an asphaltum spring, or rather, several. The principal ones are on a ranch of a Mr. Sargent. He has his ranch enclosed with good fence in two fields, one of two thousand acres; the other, through which we rode, of seven thousand acres. It is hill land, and most of it is covered with a heavy growth of wild oats, in places as heavy as a good field of oats at home—a grand field of feed, that!

The mail arrives at San Juan near ten o’clock in the night, but I walked into town and waited for it that night, and with it came a letter from Professor Whitney calling me to San Francisco for consultation. I returned to camp, hastily made my preparations, left my orders, and returned to town, for the stage started at six in the morning, too early to get in from camp. Six o’clock the next morning found me in the stage for San Francisco, where I arrived at seven in the evening. The region passed through, especially about fifty miles of the Santa Clara Valley, is the garden of California—a most lovely valley, settled by Americans, with fertile fields and heavy crops, beautiful gardens and thriving villages.

There were the usual accompaniments of a stage ride—various passengers, bristling landlords running out at the stations, dust, dirt, politics, and local news. Professor Whitney had invited me to stay at his house, where I went after taking a bath and buying and putting on clean clothes—a “biled shirt” was a luxury not enjoyed for a long time before.

Thursday, Friday, and Saturday I spent in running around, talking over plans, seeing men on business, working up geological notes, posting the Professor up on progress, etc. Every minute was occupied. How busy, bustling, hurrying, high-wrought, and excited this city seems, in contrast with the quiet life of camp!

There is much improvement going on here, even more building than usual. Business is brisk, but rates of exchange with the East are enormous—more than twice as high as they were before the War, or even three times. When I sent money home in the fall, it cost three per cent, now six to ten per cent; and so it will remain until the fear of privateers ceases.

It has been most lovely weather, but the afternoons are windy, and the air often filled with dust. No hot weather—this city is always cool—never hot, never cold.

Professor Whitney has a house several hundred feet above the city, on a hill, with a most lovely view of the city, the bay, and the hills beyond. These lovely moonlight nights the scene is surpassingly beautiful. The city below, basking in the soft light, the myriad gas lights, the bay glittering in the moonbeams, the ships, the opposite shores in the dim light, all form a picture that must be seen to be appreciated. This is indeed a lovely climate—children and women look as fresh and rosy as in England.

I meet many friends and acquaintances here; all say, “How fat you have grown,” “How camp has improved you,” “How stout and healthy you look,” and similar assurances. Every friend I have met speaks of it.

There is a very strong Union sentiment prevailing here, although the governor is Secession, and there are thousands of desperadoes who would rejoice to do anything for a general row, out of which they could pocket spoils; yet the state is overwhelmingly Union. Flags stream from nearly every church steeple in the city—the streets, stores, and private houses are gay with them—but all are the Stars and Stripes—a Palmetto would not live an hour in the breeze.

On Saturday night at ten o’clock a flag was raised on T. Starr King’s church. He is very strong for the Union, and this was for a surprise for him on his return from up country. A crowd was in the streets as he returned from the steamer. He mounted the steps, made a most brilliant impromptu speech, and then ran up the flag with his own hand to a staff fifty feet above the building. It was a beautiful flag, and as it floated out on the breeze that wafted in from the Pacific, in the clear moonlight, the hurrahs rent the air—it was a beautiful and patriotic scene.

Sunday I went to hear him preach. He is a most brilliant orator, his language strong and beautiful. He is almost worshiped here, and is exerting a greater intellectual influence in the state than any other two men.

Today I have been ordering a new wagon made, buying supplies, writing, etc., and must go soon to a meeting of the Academy of Natural Sciences which meets tonight (Monday). Professor Whitney has a grand scheme for erecting a great building for the state collections here; we are ventilating the matter here now. Today I saw my cousin, Henry Du Bois. He is working at his trade in this city.

Friday Evening, June 28.

I had expected to leave San Francisco on Tuesday morning, but Tuesday I had to meet some men to talk over matters relating to our cabinet building, so was delayed until Wednesday. We left at eight o’clock, on the top of the stage, which seat we kept all the way through, having a fine chance to see the country.

San Jose and Santa Clara are large and thriving towns, but the whole country looks dry now. The fields are all dry and yellow, the herbage on the waste lands eaten down to the very roots, the fields of grain ripe for the harvest. Many reaping machines were at work and prosperity and abundance appeared to smile on the lovely region. But how dry it looked! Hundreds

THE PLANILLA |

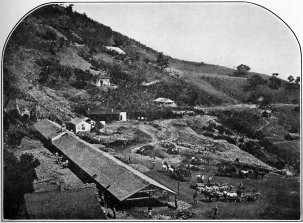

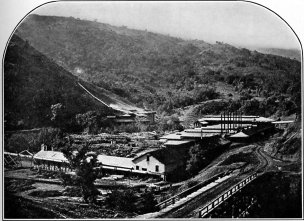

THE HACIENDA NEW ALMADEN QUICKSILVER MINE

From photographs by C. E. Watkins reproduced by heliotype

|

Much as can be said about this lovely climate, yet give me our home climate, variable as it is. This is healthy, very healthy, lovely, but it is monotonous—four more months, long months of dry air and clear sky. The budding freshness of spring, with its resurrection of life; the summer with its flowers, its showers, its rich green; autumn with its fruits, its fall of leaves, its gorgeous forests; winter, with its dead outer world, but its life at the fireside—all are unknown here. A slowly dawning spring, tardily coming, is followed by a slower, dry, arid summer. This is the climate for a lazy man, that for labor, this for dolce far niente, that for action.

We got back a little after ten in the evening, and before eleven were in camp again. It seemed like home. The soft, luxurious bed of the city had given me quite a severe cold, which my better sleep on my blankets is improving. Ah! camp is the place to sleep—sweet sleep—refreshing sleep. There is no canopy like the tent, or the canopy of Heaven, no bed so sweet as the bosom of Mother Earth.

I have not had everything to my mind in camp. Men who came into it with enthusiasm, now that the novelty has worn off, abate their zeal. I had a long talk on the matter with Professor Whitney and I was thinking of either discharging Mike, or making him “toe the mark” closer. I determined to try the latter first. He has been surly under reproof and slack in his work for some time. His work was very light and his wages high (forty-five dollars per month). But yesterday I was saved all the trouble by his coming to me and asking to quit. I discharged him without further words and he went to San Francisco this morning. He has lost a good place, but I am glad to be rid of him. He, however, thought much of me, shook me cordially by the hand on parting, and said, “Mr. Brewer, I have always got along well with you. I have never worked under a man I liked better. You are a gentleman”—very emphatic. He then took his leave without saying a word or bidding good-bye to either Averill or Guirado, with whom he had not got along so smoothly. Ere this he is in “Frisco,” as the metropolis is called.

We have changed plans. We keep in the field as late in the fall as we can, then disband and do our office work in the winter. This seems advisable. We have at least three men on the Survey who do not well sustain themselves. Two of these were employed because of influential political friends in this state, whom it was desirable to appease. It is not a pleasant matter to dismiss them, but by “disbanding” for the winter, stopping field work, we can throw them out. I feel sorry for the individuals, but believe it to be for the interests of the Survey. From the confidence with which I am consulted on these important matters, I feel that I am sustaining my place even better than I dared hope for, yet it is by no means impossible that policy may remove me too—but I hope not.

San Juan.

July 2.

My last letter was sent three days ago, but I fear for its safety; while the secession troubles last in Missouri the Overland may be troubled. I shall send the next by Wells & Fargo’s Express. Way mails in this state are so uncertain that all important letters are carried by a private express in government envelopes. The company sends three-cent letters for ten cents, and to the states, ten-cent letters for twenty cents. Here in this state it is used very largely, the Wells & Fargo mail being often larger than the government mail. We avail ourselves of it, even on so short a distance as from here to San Francisco, if the letter has any special importance or needs to go with certainty of dispatch. I have had letters two weeks in getting where they ought to go in two days with a daily mail. I very strongly suspect that some of the letters between here and home that were so long delayed were delayed on this side. One letter was from the first to the eighteenth of June coming from San Francisco to this place, one day’s ride.

War news becomes more and more exciting; the “Pony” brings all the general news far in advance of the mails. I do not dare to think where it will all end; but I trust that in this, as in other matters, an All-ruling Providence will bring all things to work together for good in the end. The Stripes and Stars wave from the peak of our tent, the ornament of the camp.

Yesterday I climbed a high steep peak about eight miles distant, a hot, toilsome day’s trip. We rode up a valley about three miles, then struck up a narrow, deep side canyon about one or two miles farther, beside a small stream. A cattle trail led up the stream, often steep and slanting, but our trusty mules managed it. Arriving at the end of this trail, we unsaddled and tied our mules beneath some trees, and mounted the ridge. It was very steep, of a rotten granite that was decomposed into a sand that slid beneath the feet and reflected the intense heat of the sun with fearful effect. It seemed as if it would broil us, and the perspiration flowed in streams. Often not a breath of wind stirred the parched, scorching air. A wet hankerchief was worn in the crown of the hat, as we do now all the time when in the sun, to save from a possible sunstroke.

A ridge was gained, which ran transverse to the main ridge we wished to reach. Three miles more along this ridge, sometimes down, sometimes up, now over sand, then over rocks and bushes, sometimes in a scorching heat, at others fanned by a breeze—at last we planted our compass on the highest crest of the Gabilan, a very sharp, steep, bold peak, some 2,500 to 3,000 feet high, probably nearer the latter. We had a most magnificent and extensive view of the dry landscape—the Salinas plain, Monterey and the Santa Lucia, the sea, the hills north of Santa Cruz, San Juan and its valley, the valley of Santa Clara beyond, an immense stretch of landscape beside.

Our canteens were exhausted and our lunch dispatched before we had arrived at the top, but the descent was easier, although the last slope before reaching our mules was intensely hot. A fine, clear, cold stream flowed in the canyon—and how sweet it tasted!—but it sinks before entering the valley of San Juan. A ride back to camp, a sumptuous dinner prepared by Peter, then a lounge under the large oak that stands by our camp, in the delicious breeze, then the comet in the west at night, made us forget the toils of the day.

There is a very curious meteorological fact connected with these hills. It is cooler in the large valleys, and hotter on the hills. A delicious cool breeze draws up the larger valleys from the sea, sometimes far too violent for comfort, but always cooling. It often does not reach the hills, so that rising a thousand feet ofen brings us into a hotter instead of cooler air. The hot weather is now upon us, much hotter than in the immediate vicinity of the sea. One does not so notice it if still or in the shade. Today it is by no means oppressive in the shade for there is a delicious breeze. It has not been above 90° F. under the tree where I write this during the day, but out in the sun or in exercise it is hot, very hot.

This morning at ten, when the thermometer was 80°, I laid it out in the sun and in fifty minutes it ran up fifty degrees, or to 130°. There the graduation stopped, so I could not measure the actual heat; it was probably about 140°, although it sometimes rises to 165° or 170° F. in some of the valleys of this state! Surely the state is rightly named from calor, heat, and fornax, furnace—a heated furnace, literally2

I have not been so active today; it is too hot to enjoy work. Iron articles get so hot that they cannot be held in the hand; water for drinking is at blood heat; the fat of our meats runs away in spontaneous gravy, and bread dries as if in a kiln. You can have no idea of the dryness of the air. When I wash my handkerchief I don’t “hang it out” to dry, I merely hold it in my hand, stretched out, and in two or three minutes it is dry enough to put in my pocket.

July 4.

The “Glorious Fourth” is at hand, but I am quiet in camp, and alone. All have gone into town to celebrate. Yesterday, while hammering a very hard rock, to get out a fossil, a splinter of the stone struck me in the eye and hurt it some. It is by no means serious, but somewhat painful, and I, therefore, will keep quiet in camp today to prevent any inflammation or bad turn. With a handkerchief bound over it, it feels quite comfortable, and I apprehend nothing serious. I have one eye left for writing.

Yesterday I rode five or six miles to visit a range of hills north of the town, across the San Benito River. They were gentle, grass-covered hills, or rather oat-covered hills, enclosed in enormous fields and rich in pasturage. The oats were in places as heavy and thick as in a cultivated field, but generally not so heavy. They are ripe and dry now. There was some stock in, but the land here is not nearly so heavily stocked as it is farther south. There were trails up the sides, which in places were quite steep, but we rode to the summit, eight hundred or a thousand feet above the plains, an isolated ridge between the plains of San Juan and the stream on the north. That stream, tributary to the Pajaro, is in a wide valley, but the stream is a small one. The San Benito, which at times is a wide and rapid river, is now a small stream, scarcely ankle deep, filtering over its sandy bed, except where it passes through rocky hills, where it is quite a river. The view from our elevation was quite extensive and beautiful. We were back at camp before night.

Peter acts the part of cook now until we can get another suitable person. Would that he could be induced to keep the office. He is as neat and skilful as if he had served an apprenticeship in a French restaurant. We had a sumptuous dinner, but with few courses. With his revolver he had shot a large hare, which was served up in splendid style.

On our arrival in the state last fall we met a Doctor Cooper, who was very anxious to get the place as zo÷logist to our Survey or as an assistant in that department.3 He was a young man, scarcely my age, but had been over most of the United States, had crossed the plains several times, had seen much of California, and all of Washington and Oregon. He had written a large book (with Doctor Sulkley) on the Natural Productions of Washington Territory, was well posted in his department, was a man of more than ordinary intellect and zeal in science, but I fear not a very companionable fellow in camp. He was employed during the winter as surgeon at Fort Mohave, on the desert on the southeastern border, and Professor Whitney employed him to collect plants and make observations for us there. He was just returning to San Francisco by stage, when he stopped over night here, and we most unexpectedly met him last night. I think Professor Whitney will employ him, at least for a time. I have got many items for him, and he has collected some four or five hundred species of plants from the deserts for me.

This place is very dull for the day; everybody has gone to Watsonville, fourteen miles distant, where there is a celebration. Peter burnished his harness, harnessed the mules, and with flags on their heads, has gone to town in patriotic style. But it is hot here; the daily breeze has not yet sprung up, the flag droops lazily from our tent, and the thermometer is 85° to 90° in the tent. About noon the breeze will begin and it will be cooler.

Sunday, July 7.

Yesterday I rode eight or ten miles, visiting some tar springs and oil works, where oil for burning is made from asphaltum.

We received a letter a day or two ago from Professor Whitney that he would be down either Saturday or Monday, for certain, so I suppose he will surely be here tomorrow, after our long suspense in waiting for him. He writes, and other letters and the papers confirm it, that several shocks of earthquakes took place last week in San Francisco, and reports come in from other parts of the state. I think that I have before told you that nearly or quite the whole of this state is subject to earthquakes. There will never be a high steeple built in the state, and in San Francisco the loftiest houses are but three stories high, the majority only two. There are two hotels four stories, but all old residenters will not stop at them for fear of having them shaken down over their heads. The shocks last week (six principal shocks) were quite severe, much more so than usual, and caused much alarm. Our office is in the Montgomery Block, a high three-story stone building, full of offices, but a building many are afraid of. Professor Whitney says he thinks that all of the occupants ran out into the street except him, and says that the building rocked and swayed finely. The city was in terror, the streets filled in an instant, everyone excited. No business was urgent enough to keep a man at it; men rushed into the streets from barber shops with their faces lathered and towels about their necks; men even rushed naked from baths, but were stopped before reaching the city in that primitive costume. We have perceived no shocks, but they were reported in the vicinity two weeks ago.

I went to Mass this morning in the Mission Church.4 It is a fine old church, with thick adobe walls, some two hundred feet long and forty feet wide, quite plain inside, and whitewashed. The light is admitted through a few small windows in the thick walls near the ceiling, windows so small that they seem mere portholes on the outside, but entirely sufficient in this intensely light climate, where the desire is to exclude heat as much as to admit light—so the air was cool within, and the eyes relieved of the fierce glare that during the day reigns without.

The usual number of old and dingy paintings hung on the walls, the priest performed the usual ceremonies, while violins, wind instruments, and voices in the choir at times filled the venerable interior with soft music. I never wonder that the Catholic church has such power over the feelings of the masses, especially when I compare its ceremonies with such as I saw in a Protestant church here. A congregation of perhaps 150 or 200 knelt, sat, or stood on its brick floor—a mixed and motley throng, but devout—Mexican (Spanish descent), Indian, mixed breeds, Irish, French, German. There was a preponderance of Indians. Some of the Spanish se˝oritas with their gaily-colored shawls on their heads, were pretty, indeed. It is only in a Roman church that one sees such a picturesque mingling of races, so typical of Christian brotherhood.

With scarcely enough Protestants here to support one church well, there are three churches, wasting on petty jealousies the energies that should be exerted in advancing true religion and rolling back the tide of vice swelling in the land.

Tuesday, July 9.

Last night Professor Whitney arrived, bringing with him a topographer,5 so today our company is quite lively again. I have returned from a trip on the Gabilan hills—quite a ride. Tomorrow the Professor and I will go to Monterey to be gone three or four days.

San Juan.

July 14.

It is a quiet Sunday, and, although the wind blows, it is too hot to write in the tent, so I write in the shade of a fine oak by our camp. My last was sent the first of last week, by express.

Well, Professor Whitney arrived on Monday night. Tuesday was spent in arranging some small matters, and Wednesday, July 10, we started for Monterey—Professor Whitney, Averill, and I. We were up at dawn, had our breakfast, and by half past five were in our saddles. I took one of the team mules to ride, being stronger than my little one. The early morn was clear, but soon the fog rolled in from the sea, enveloping the hills.

It was thirty-nine miles to Monterey, but a mountain trail shortened the distance some five miles, so we took that, although neither of us had ever traveled it. First up a canyon, then across the ridge about a thousand feet high, by a steep winding trail, then down on the other side. Our trail was often obscure, mingling with cattle paths, and the dense fog obscured all landmarks, but in about seven miles we emerged on the Salinas plain, where we took the stage road and crossed the plain. There was some wind, and it was cool, but the fog did not entirely obscure the hills. We stopped at Salinas, and fed both ourselves and our mules, then rode on. On striking the valley that leads up to Monterey for about sixteen miles we had hotter air, but not much dust. We arrived before night, and found the town (city, I should say—a city of six hundred or eight hundred population!) in much excitement over a recent discovery of silver mines in the vicinity, but which I don’t think will ever prove of any value.

The next morning we went on to Pescadero Ranch, found no one at home, so climbed in by the window, opened the back door, and “took possession.” This was the place where we had encamped so long, you recollect. I had found the geology too much for me, and I wanted Professor Whitney to see it; hence our visit to Monterey, for it was a matter of some importance to settle. Mr. Tompkins, the owner of the ranch, had tendered us its hospitalities, but his buccaro, Charley, was gone—all the dishes dirty on the table, and no provisions to be found, no candles, no wood cut. We spent the day looking up the objects we had come to see. Averill went into town, four miles, and got supplies, we washed up the dishes, got our dinner and supper, and made ourselves comfortable. Professor Whitney was as much interested as I had been, both in the geology and in the abundant life in the sea.

I wish I could describe the coast there, the rocks jutting into the sea, teeming with life to an extent you, who have only seen other coasts, cannot appreciate. Shellfish of innumerable forms, from the great and brilliant abalone to the smallest limpet—every rock matted with them, stuck into crevices, clinging to stones—millions of them. Crustaceans (crabs, etc.) of strange forms and brilliant colors, scampered into every nook at our approach. Zo÷phytes of brilliant hue, whole rocks covered closely with sea anemones so closely that the rock could not be seen—each with its hundred arms extended to catch the passing prey. Some forms of these “sea flowers,” as they are called because of their shape, were as large as a dinner plate, or from six to twelve inches in diameter! Every pool of water left in the rugged rocks by the receding tide was the most populous aquarium to be imagined. More species could be collected in one mile of that coast than in a hundred miles of the Atlantic coast.

Birds scream in the air—gulls, pelicans, birds large and birds small, in flocks like clouds. Seals and sea lions bask on the rocky islands close to the shore; their voices can be heard night and day. Buzzards strive for offal on the beach, crows and ravens “caw” from the trees, while hawks, eagles, owls, vultures, etc., abound. These last are enormous birds, like a condor, and nearly as large. We have seen some that would probably weigh fifty or sixty pounds, and I have frequently picked up their quills over two feet long—one thirty inches—and I have seen them thirty-two inches long. They are called condors by the Americans. A whale was stranded on the beach, and tracks of grizzlies were thick about it.

The air was cool, and at times fog rolled in from the Pacific, as it often does there. We found beds and blankets, and after breakfast the next day rode to Point Lobos, then over some high hills back of Carmelo Mission, but the fog obscured the fine views I wanted Professor Whitney to see.

We descended into the valley, and called at Judge Haight’s, where we had visited before. Professor Whitney soon returned to Pescadero, but the young ladies pressed us so cordially to stay to tea that Averill and I did, and had a most pleasant visit. It is a very intelligent and pleasant family indeed. Our tea, and a walk we took with the ladies, detained us so that we had to ride home after dark. This would be a light matter at home, but not so here, where for three or four miles the trail led through a woods or dense chaparral as high as our heads or higher, where grizzlies sometimes dispute the right of way, and across a dark gulch with almost perpendicular sides, where none of you would trust yourselves to ride by broad daylight.

Saturday morning we had intended to start back, but were detained on our way, in Monterey, until noon, so we only reached Salinas, twenty miles from Pescadero.

An excitement in the dull monotony of the little town was occasioned by the arrival of an English brig, of only 180 tons, six months out from London. She had not seen land during all that time. She was in a terrible condition, and had put in in distress. Provisions and water very scant and bad all the way, now exhausted, men sick of the scurvy, captain dead of the same disease, second mate and boatswain lost in a storm, sailors decidedly used up—their story was a pitiful one.

As I said, we stopped last night at Salinas. This morning we were up early, and were off, crossing the plain, then over the mountain trail again, and by ten o’clock were at camp, where we found all well. We had our blankets washed during our absence. We are resting quietly this lovely afternoon after our long ride.

NOTES

1. This letter was lost. Professor Brewer’s notebooks, however, show that camp was at Pescadero and Monterey June 1 to 12, at Natividad (near Salinas) June 12 and 13, and from June 14 at San Juan.

2. The origin of the name “California” has been the subject of much discussion. In 1862, Rev. Edward Everett Hale called attention to the fact that the name appeared intact in an old Spanish romance, Las Sergas de Esplandißn, and was almost certainly familiar to Cortez and his contemporaries who first placed it on Pacific shores. That in some way the name came from this source is now the prevailing opinion. Prior to this explanation, however, there were many ingenious speculations, most of them taking the form of compounds from Latin and Greek roots; some seeking an Indian origin. The subject is discussed in Charles E. Chapman, A History of California: The Spanish Period (1921), chap. vi; in Ruth Putnam, California: The Name, “University of California Publications in History,” Vol. IV, No. 4 (December 19, 1917); and in the California Historical Society Quarterly, 1922), 46-56; Vol. VI, No. 2 (1927), 167-168.

3. James Graham Cooper (1830-1902) was the son of William Cooper (ornithologist, friend of Audubon, Nuttall, Torrey, and Lucien Bonaparte, and one of the founders of the Lyceum of Natural History of New York). He was graduated in 1851 from the college of Physicians and Surgeons, New York; in 1853 he contracted with Governor Isaac I. Stevens, of Washington Territory, as physician of the northwestern division of the Pacific Railroad Survey. In addition to his medical duties he made botanical and zo÷logical collections and meteorological observations. He continued to engage in similar work up to the time of his connection with the California Survey. The results of his work under Whitney are preserved in a publication of the Survey issued in 1870, Ornithology, Vol. I, “Land Birds,” edited by F. S. Baird from Dr. Cooper’s manuscript and notes. In his own North American Land Birds, Professor Baird remarks: “By far the most valuable contribution to the biography of American birds that has appeared since the time of Audubon, is that written by Dr. J. G. Cooper in the Geological Survey of California.” Dr. Cooper was commissioned by Governor Lowe, in 1864, Assistant Surgeon, 2d Cavalry, California Volunteers. In 1866 he married Rosa M. Wells, of Oakland. He lived in Ventura County from 1871 until 1875, when he took up his residence in Hayward, where he lived for the remainder of his life. The Cooper Ornithological Club, named in his honor, was organized in 1893. (References: “Dr. James G. Cooper. A Sketch,” by W. O. Emerson, in Bulletin of the Cooper Ornithological Club, Vol. I, No. 1, Santa Clara, January-February, 1899; “In Memoriam,” by W. O. Emerson, and “The Ornithological Writings of Dr. J. G. Cooper,” by Joseph Grinnell, both in The Condor, Vol. IV, No. 5, Santa Clara, September-October, 1902.)

4. La Misiˇn San Juan Bautista was founded 1797.

5. Charles Frederick Hoffmann was born at Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, 1838, and was educated in engineering before coming to America. In 1857 he was topographer for Lander’s Fort Kearney, South Pass, and Honey Lake wagon-road survey. He came to California in 1858. Next to Whitney himself, he had the longest connection with the California State Geological Survey, remaining through all vieissitudes until its discontinuance in 1874. During a hiatus in the Survey, 1871-72, he served as Professor of Topographical Engineering at Harvard. In 1870 he married Lucy Mayotta Browne, daughter of J. Ross Browne. For many years he was associated with his brother-in-law, Ross E. Browne, in the practice of mining engineering, for a time at Virginia City, Nevada, later at San Francisco. He also managed mines in Mexico, and at Forest Hill Divide, California, and investigated mines in Siberia and in Argentina. During the latter part of his life he lived in Oakland, where he died in 1913. The importance of his work on the California Survey and its influence upon the development of topography in the United States have been mentioned in the introduction to this volume.

| Next: Chapter 2 • Contents • Previous: Book 1 |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Up & Down Calif. > top2 >

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/up_and_down_california/2-1.html