Sherman Day

Gov. John G. Downey

Rev. Laurentine Hamilton

Rev. Thomas Starr King

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Up & Down Calif. > 1861 Chapter 3 >

| Next: Chapter 4 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 2 |

Pacheco Peak—Santa Cruz—Mountain Charlie’s—Governor Downey—New Almaden Mine—A Visit to San Jose—Social Life at New Almaden—Climbing Mount Bache—Enriquita and Guadalupe Mines.

Santa Cruz.

August 4, 1861.

We had intended to leave for Santa Cruz on Tuesday, July 30, so on Monday made our preparations, but that afternoon Professor Whitney telegraphed to me to wait until Thursday for letters and orders. This gave us three days on our hands. I resolved to visit Pacheco Peak, about twenty-eight miles northeast of San Juan, so Hoffmann and I started on our mules. Averill in the meanwhile went to Monterey for a horse he had bought.

I will describe our trip. First a ride of eighteen miles across the dead-level plain, tedious and monotonous. The Gabilan Range on the south, the Monte Diablo Range on the north, to which Pacheco, Santa Ana, and other peaks belong. To one who has never tried riding on a level plain, no description is adequate to cause a full realization of its tediousness.

The distance seems near, very near, to begin with. Pacheco Peak rises in such full view from our camp, its rocks and ravines every one so distinct that any of you would estimate its distance, without California experience, as five or six miles at most, instead of the near thirty we must ride to reach it—twenty, at least, in a straight line. The road is crooked, several miles are lost by its windings; the air is hot as we plod across it; league after league is passed without the aspect of the scene changing; the Pacheco seems no more near, nor the Gabilan no more distant, than it did an hour before. But at last a belt of scattered oaks is entered. Then we strike up a canyon, on the Pacheco Pass, through which the Overland made the crossing of this chain. Eight miles up this canyon, by a good road, brought us to Hollenbeck’s tavern, in the heart of the chain at the foot of Pacheco Peak and at some elevation above the plain.

We had ridden the twenty-four miles from camp, but were not too tired to climb the peak, and as time was valuable and as it was still only two o’clock, our mules were put out, our dinner was got, and we started. There is a good and easy trail most of the way up, three or four miles, made by cattle and sheep. The wind had been high during the middle of the day and still shrieked through the canyons; it had annoyed us much on coming up the pass by the dust it raised.

Up, up, we toiled. The peak rises like a very sharp cone, forty to forty-six degrees’ slope on each side, about six hundred feet above the mass of mountains around—a sharp, steep, conical peak, towering far above everything near. It has generally been put down as a volcano (extinct) and the rock on top as lava, hence it was important to visit it. All wrong, however. The rock was the same as the rest of the chain, metamorphic, only a little more altered by heat. The ascent of the last cone was steep and laborious, but it was accomplished, and we stood on the highest rock of the summit—about 2,600 or 2,700 feet above the sea, and 2,500 feet above the plain on either side.

Strange, that the strong current of wind that sweeps through all the valleys scarcely reaches us here, only a gentle breeze plays over the summit. Below, to the south lies the great San Juan plain, its division into two parts, one running to Gilroy, the other to San Juan. It is four or five hundred square miles in extent, but it seems not one-fourth of that. A cloud of dust rises from it, raised by the high wind like a gauze veil two to three thousand feet high, but the Gabilan Mountains, the Salinas plain more obscure through the gaps, and the Santa Cruz Mountains to the west, are all visible.

The chain we are on is about thirteen or fifteen miles through the base, rising in an innumerable number of ridges to the height of about two thousand feet, furrowed into countless canyons, the whole elevated mass running northwest and southeast. To the east is the great Tulare, or San Joaquin, Valley, but a dense cloud of dust rises from it and forms an opaque white veil that shuts out the view of the Sierra Nevada beyond. We have a view of eighty or a hundred miles of the chain we are on, with the higher peaks to the east of us, some of which rise about three thousand feet, but are without names.

When you go off in rhapsodies over the grandeur of Mount Tom or Mount Holyoke, around which cluster so many poetical associations, think that the former is less than 900 and the latter but 1,200 feet high, with all their poetry! Here, peak after peak raises its grand head against the sky, and the addition of either of the Massachusetts heroes to the height of any one of them would scarcely be noticed; yet these peaks are not only unknown to fame, but are even without names. I was about to say, “Born to blush unseen, and waste their grandeur on the desert air.”

The mountains are covered with oats, now dry, giving them a soft straw color. We lingered on the peak until the sun was nearly set, the shadows long and dark on the plain, the canyons dark and gloomy, the sunny slopes bathed in the softest golden light. We returned to our tavern, ate supper, talked in the barroom on Secession at home, then retired—Hoffmann to fight fleas all night, I to congratulate myself that they do not bite me but only crawl over me in active troops. I wished for my blankets that I might go out and sleep.

Wednesday we returned to camp—a terribly windy day—and found Peter back. He had run out of money and left Sleepy thirty miles back. Michael, also, was back; he had left us, you recollect, some weeks ago, but came back so penitent that I concluded to try him once more.

August 1, Hoffmann and I again climbed Gabilan Peak, about seven miles from camp, for the sake of measuring it and getting fresh bearing from its summit. It was 2,932 feet above camp and I suppose about 3,100 feet above the sea—quite a peak. I dispatched Guirado, meanwhile, after Sleepy, and to our surprise he got him into camp the next forenoon, having traveled all night in the cool. The mule was much better, but we had to leave him at San Juan.

Friday, August 2, we intended starting early. We were up and had our breakfast at five o’clock, but Averill did not arrive. We packed up and waited all the day, or at least until 1 P.M., then started on without him. We came on about eighteen miles, first over the hills, then across the most lovely Pajaro Valley, a little bottom five or six miles wide and eight or ten long—a perfect level—an old lake filled in as is shown by its position and by the terraces around its sides. On the river is Watsonville, a neat, thriving, bustling, American-looking little town. The country around is in the very highest cultivation, divided into farms, covered with the heaviest of grain, or a still heavier crop of weeds. Several threshing machines were seen at work in the fields, and the hum of industry in the little town sounded American-like.

I ought to mention a little item. The squirrels were very thick around our San Juan camp—they came out of their holes to eat the barley near our mules. Guirado killed seven at one shot with the shotgun, and Peter, one morning, shot twenty-one in four shots. The morning we left, while we were waiting for Averill, as I sat making some calculations, I kept my revolver by my side to shoot at the squirrels when they came out. I killed five in thirteen shots, so you see I am getting to be quite expert with the “instrument.”

We camped about three miles from Watsonville and came on here to Santa Cruz yesterday, Saturday. Santa Cruz is a pretty little place. We camped at a farmhouse about a mile from town, near the seashore. The church bells on Sunday morning reminded me of home, and as I had been in a Protestant church but twice since last November, I resolved to go.

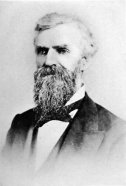

Sherman Day |

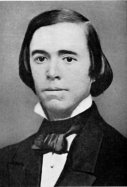

Gov. John G. Downey |

|

| ||

Rev. Laurentine Hamilton |

Rev. Thomas Starr King |

|

Monday, August 5, I visited some limestone quarries and lime kilns near town. Lime is burned for the San Francisco market. All the arrangements are very fine and complete, and about five thousand barrels per month are burned. The proprietor, Mr. Jordan, was very kind and showed me around. These people own a large ranch, raise their own cattle, keep their own teams, cut their own wood, etc. They have schooners for shipping the lime, and the wagons they use in drawing it to the wharf are enormous. These wagons draw from 90 to 150 barrels to a load, each barrel weighing 200 to 250 pounds—surely quite a load.

The mountains back of Santa Cruz are partially covered with magnificent forests of redwood, pine, and fir—tall, straight, beautiful.1 Many of the redwoods are from ten to twelve feet in diameter; one is nineteen or twenty feet in diameter. You cannot appreciate how tall and straight these Californian evergreen trees are. Mr. Jordan cut a fir for a “liberty pole” that was 14 inches in diameter at the butt, and 2 1/2 inches where it broke off at the top, perfectly straight, and 171 feet long. In falling it broke in the middle and was spliced. I saw some magnificent sticks cut from these fir trees. The redwood is by far the most valuable timber of California. It grows only on the mountains near the coast. It is between a pine and a cedar—the wood is as coarse grained as pine, but of the color and durability of red cedar. The trees grow of enormous size, very large and tall, with a habit something like our hemlock, only the trees swell out more at the base. The “giant trees” of the Sierra Nevada are of the same genus, and much like it in all respects, only larger.2 The wood splits well and all the cabins in the mountains are built of it—fencing, timber, everything. Northward they grow still larger. Chester (Averill) tells of seeing in Humboldt County a house and barn—roof, timber, boards—all—and several acres fenced—with one tree. Such is the redwood.

Tuesday, we went to see some noted rocks called “The Ruins,” six or seven miles back in the mountains. We found them a humbug—nothing near what we expected—some were small outcrops of sandstone, which had weathered in curious forms, some were in tubes like chimneys two or three feet high. These had been regarded as artificial works—“chimneys of furnaces”—and at one time a company was actually formed to dig for treasures that might be buried there. So inflamed is the public mind here on hidden treasures!

The town stands on a terrace about sixty feet above the sea, a table that runs back a mile, where another terrace rises—an old sea beach about 180 feet higher, which may be traced for miles. Wednesday we spent in examining these terraces and measuring their heights. The town is prettily situated on a clear stream, the San Lorenzo River. The place looks quite American—neat homes, trees in the yards, gardens, flowers, and American farms around. Even the old adobe mission church is nearly torn down and a neat wooden church stands by its side, the old adobe walls and ruins telling of another race of builders. There are some Spanish people and Indians left yet, but the town is American.

Thursday, August 8, we left for the New Almaden Mines, striking north through the mountains, where a fine road runs to San Jose and Santa Clara. It is the most picturesque road we have yet traveled. We struck back into the mountains directly behind the town, wound up valleys, through and across canyons, over ridges, and along steep hillsides. Sometimes the way lay along a bare hillside, giving a fine view, but oftener in dark forests, where enormous trees shot up on every side; sometimes singly, their giant trunks like huge columns supporting the thick canopy of foliage above; at others groups of trunks started from a great rooted base, half a dozen or more trees together, their spreading tops forming only one head of immense size. Laurels, or bay trees, with their fragrant foliage, firs, pines, oaks, mingled in that picturesque scene, which continually changed with every turn of our ever winding road.

We at last struck a ridge and followed it some miles, and at 2 P.M. camped on the summit at “Mountain Charlie’s,” about two thousand feet above the sea. Evergreen oaks grew around, a lovely place to camp, and a little pond overgrown with sedge and rushes lay beside the house. After dinner we went on a hill near camp, a few hundred feet above it, for bearings and observations. The view was both extensive and lovely, one of the prettiest I have yet seen. Around us was the sea of mountains, every billow a mountain; deep dark canyons thread them, the form and topography very complicated, the geological structure very broken. Redwood forests darken the canyons on the west toward the sea, chaparral covers the ridges on the east. Some of the peaks about us are very high—Mount Bache3 rises in grandeur nearly four thousand feet, Mount Choual and others over three thousand feet. To the south lie the whole Bay of Monterey and a vast expanse of ocean.

The beautiful curved line of the bay seems like an immense semicircle, thirty-five miles across, but every part of the arc distinct. Monterey is obscured by fog, but the mountains rise above it in the clear air. Fog forms at the head of the bay and rolls up the great Salinas Valley as far as we can see, but we are far above it and looking on the top of it—it seems like a great arm of the sea, or a mighty river, stretching away to the distant horizon. The mountains beyond Monterey also rise above it, in the clear air. Each ridge is distinct—the range of Point Pinos, the Palo Scrito hills, while in the blue dim distance rise the high peaks of the center of the chain, ninety or a hundred miles distant from us. Southeast, over the lower ridges, rises the Gabilan, thirty-five or forty miles distant; nearer, the high ridges of our own chain.

The “chain” is here a series of ridges and we are near the middle. Through a break we can see the lovely Santa Clara Valley in the north, and the towns of Santa Clara and San Jose, eighteen or twenty miles distant, are in full view—the separate houses can be distinguished with our glasses.

Some plants were collected, barometrical observations made, supper eaten, and in the twilight we sang songs beneath the branches of the trees until we turned in and watched the stars twinkling throught the leaves in the clear, blue mountain air.

Friday found us astir early, and we came on. The valleys and canyons and the distant bay were all covered with dense fog, but we were above it, looking down on its top. As the sun came up this fog seemed a sea of the purest white, the mountains rising through it as islands and the tall trees often rising above its surface. It was now tossed into huge billows by the morning breeze, and as the sun rose higher it curled up. The scenes gradually shifted as the curtain rolled away, and the mountain landscape was itself again.

We came on, first down a gradual slope for about nine or ten miles, then down a canyon that breaks through the outer ridge, until we emerged into the Santa Clara Valley. We passed over the tableland at the base or among the foothills, about twelve miles, and camped near the mines of New Almaden.

New Almaden Mines

August 17.

On the way to the New Almaden Mines we met Governor Downey4 and his wife and sister in a carriage with driver. Guirado was ahead, and as I came up he introduced me. I was decidedly in a “rig” for introduction to such society—buckskin pants, leggins, dirty gray shirt, without coat, vest, cravat, or suspenders, begrimed with the dust of our very dusty road—yet it was all the same. We stopped and talked a short time, then passed on.

He is a wealthy man, Irish, has a ranch worth $300,000, has risen from the ranks, has a Spanish wife, is a zealous Catholic—so has the elements of political popularity here. President Lincoln has made a requisition on this state for mounted volunteers to protect the Overland mail route, and the Governor has offered Guirado a first lieutenant’s commission, decidedly a fine opening, so he left the party yesterday morning.

Well, we arrived. A most lovely little town has sprung up by the furnace—neat houses on a long street, with a row of fine young shade trees, green yards, pleasant gardens, etc. The superintendent, Mr. Young,5 is absent. He lives in most magnificent style, like a prince, has a wife half Spanish-Californian, half Scotch, who has a lot of single sisters, the Misses Walkinshaw, lovely girls, of whom more anon.

Mr. and Mrs. Whitney were at the house of Mr. Day, the mining engineer, and head man in Mr. Young’s absence. We were introduced to the ladies in the same unpresentable costume, which excited much mirth. It was the first time I had seen Mrs. Whitney since taking the field. She scarcely knew me in my bronzed, burnt skin, robust looks, and un-Parisian costume, and she failed entirely to recognize Averill, so has he changed by exposure and the growth of a tremendous beard. We were soon camped below the town, by a stream, in a pretty spot. Another rig donned (colored shirts, of course, but clean), and I returned to talk about affairs with Professor Whitney. He had to go to a party, so I went up late in the evening to talk with him after his return.

Saturday, August 10, we visited the principal mine of New Almaden, with Mr. Day to guide and conduct us. It is probably the richest quicksilver mine in the world, and is worth one or two million dollars. The pure red cinnabar (sulphuret of mercury) is taken out by the thousands of tons, and the less rich by the hundreds of thousands of tons. The mine is perfectly managed and conducted. The main drift is as large as a railroad tunnel, with a fine heavy railroad track running in. Six hundred feet in and three hundred feet below the surface of the hill is a large engine room, with a fine steam engine at work pumping water and raising ore from beneath. The workings extend 250 feet lower down. We went down. The extent of the mine is enormous—miles (not in a straight line) have been worked underground in the many short workings, and immense quantities of metal have been raised. We were underground nearly half a day, then came out and had a sumptuous dinner at a French restaurant near, then climbed the hill over the mine.

A ridge runs parallel with the main chain of mountains, about 1,700 feet high, in which are three mines, of which this is the principal one. The view from “Mine Hill” is perfectly magnificent—over the region east and north, with the bold, high peaks back of it.

Mrs. Whitney went to San Francisco that day. Professor Whitney returned on Sunday, August 11, when I rode down twelve miles to San Jose with him.

San Jose (always pronounced as if one word, San-ho-zay´) is a pretty town in the Santa Clara Valley, on a level plain. Orchards, gardens, pretty houses, fruit, fertile fields are the features—a bustling, thriving town, of probably six or seven thousand inhabitants. The roads at this season are dusty beyond description and the town looks accordingly.

I bade good-bye to Professor Whitney and then went to church—Mr. Hamilton’s church (of Ovid).6 He was absent, but Mrs. Hamilton (formerly Miss Mead, you remember, of Gorham and Ovid) was there, and on my going up to her after service she was as much surprised as if I had really dropped from the clouds, as she asked me if I had—although no clouds had been seen here for months. I went to the parsonage, a neat house next the church, where they are living very neatly and comfortably indeed. She has become thoroughly Californian, is delighted with the country, climate, people, etc. A pretty little boy with light hair and fine gray eyes was running around, the pride of his mother’s heart. Mr. Hamilton had been absent six weeks in Oregon, but was daily expected back. I need not say that we had a pleasant chat until it was time for me to return.

We were down with the wagon. I ran around town but very little, for the climbing up and down so many hundred feet of ladders the previous day in the mine had told fearfully on my lame knee, and I began to be anxious. I bought some medicine for it, and we returned to camp at nightfall. Monday I was so lame that I resolved to stay in camp quietly and recruit my knee before it grew worse, as I had some mountain climbing to do during the week.

In the evening I rode up to Mr. Day’s.7 He has two daughters now home. A young lady was visiting, and half a dozen came in, and a lively time we had of it. We were invited to a horseback ride the next afternoon with some of the ladies. Mr. Day is a son of President Day of Yale College, is a fine man with a very fine family, has been here twelve years, and many a chat we have had about New Haven and old Yale. The room I occupied in college was his old room at home.

Tuesday, August 13, I went to the mines and collected specimens. The mines are about two miles from the furnaces, on the hill. We collected two or three boxes of specimens, then returned. The furnaces are complete, and about three thousand flasks (seventy-five pounds each) of quicksilver are made each month. More might be made if desired, but that is enough for the market. An old furnace has been taken down, and the soil beneath for twenty-five feet down (no one knows how much deeper) is so saturated with the metallic quicksilver in the minutest state of division, that they are now digging it up and sluicing the dirt, and much quicksilver is obtained in that way. Thousands of pounds have already been taken out, and they are still at work.

No wonder that there has been such legal knavery to get this mine, when we consider its value. Every rich mine is claimed by some ranch owner. These old Spanish grants were in the valleys; and, when a mine is discovered, an attempt is made to float the claim to the hills. Two separate ranches, miles apart and miles from the mine, have claimed it, and immense sums expended to get possession. The company has probably spent nearly a million dollars in defending its claim—over half a million has been spent in lawyers’ fees alone, I hear.8 The same at New Idria—it was claimed by a ranch, the nearest edge of which is fifteen miles off!

And this is only a sample of the way such things go here. Were I with you I could relate schemes of deeply laid fraud, villainy, rascality, perjury, and wickedness in land titles that would entirely stagger your belief, yet strictly true. The uncertainty of land titles and the Spanish-grant system are doing more than all other causes combined to retard the healthy growth of this state.

But to our horseback ride. Mrs. Young’s Scotch father, Robert Walkinshaw, having died, the children now live here. There are several girls left, all beautiful. Professor Whitney thinks one the most lovely lady he has seen in the state. I hardly go to that length. They ride every afternoon and invited us to ride with them. Three of them, with Miss Day, a Miss Clark of Folsom, a young Englishman, Averill, and I, made up the party. It was the pleasantest time I have had in the state. We started at five o’clock and rode five or six miles east to the top of a hill that commands a lovely view of the Santa Clara Valley and the opposite mountain chain.

I wish you could see those Mexican ladies ride; you would say you never saw riding before. Our American girls along could not shine at all. There seems to be a peculiar talent in the Spanish race for horsemanship; all ride gracefully, but I never saw ladies in the East who could approach the poorest of the Spanish ladies whom I have yet seen ride. I cannot well convey an adequate conception of the way they went galloping over the fields—squirrel holes, ditches, and logs are no cause of stopping—jumping a fence or a gulch if one was in the way. The roads are too dusty to ride in, so we rode over the hills and through fields, sometimes on a trail, sometimes not. We took tea at Mrs. Day’s, then were invited to Mr. Young’s, where we spent a pleasant evening. My lame knee was better, but still bad enough as an excuse for not dancing.

Wednesday I went to the Enriquita Mine, about six miles distant. It is a poor mine, but yields some quicksilver. It is twelve miles or more distant by the road, but not half that distance by the trail we took across the hills. My knee was much better, but I refrained from using it much.

It was desirable to ascend the mountains about five miles back, in a direct line, from the mines. Professor Whitney was anxious to have them examined. They form a long ridge, covered with chaparral, rugged, forbidding, but not so steep as some we have seen. The highest point, Mount Bache, is the highest point of this chain, and as it was a Coast Survey signal station its height had been carefully ascertained. Because of its known height, we wanted to test our aneroid barometer.

A good trail had once been cut to the top, and the view was so grand that several ladies wished to make the ascent with us; Mr. Day and several other gentlemen also wanted to go. A man was sent the day before to reconnoiter part way. He declared it to be impossible for ladies, so they were left behind. Five were to go, and five o’clock named as the hour of starting. I suggested a later hour, as previous experience had taught me the uncertainty of getting the outside party out so early, although we could start at any time; but five was the hour set.

Thursday, August 15, we were up before four, ate our breakfast by the light of the stars, and at five were on hand at the rendezvous, punctual, as we always are. Our aneroid had not arrived the previous evening by express, as was expected, but we found the expressman—he had it—returned to camp, unpacked it, got our other barometer, got back—the rest not ready. Two long hours were consumed before we got the party off, eight persons instead of five—Averill, Hoffmann, and I, of our party, Mr. Day, Wilson (a young Englishman who had never climbed a mountain), a Doctor Cobb, a Mr. Reed, and our guide. Mrs. Day insisted on putting up our lunch, so we could not well carry along any other. We were to ride to the foot of the chaparral, about 1,500 feet above camp, leave our horses by a spring—then, two hours’ climb to the summit, 2,000 feet above. A single gallon canteen was to be amply sufficient for the ascent—since there was such a fine spring on the summit! To be sure, none of the party had ever been there, but we had the minutest directions.

Well, we reached the water, unsaddled, found good water but very scanty; it took an hour to get enough for our horses and mules. I hung up my barometer for observations, when we found the aneroid smashed—a total wreck. I had not examined it in the morning; Averill had carried it, and it must have been broken in the express on the way from San Francisco.

It was ten o’clock when we started from there, the time we were to have been at the summit, at the very latest. Our visitors “pitched in” vigorously on the start. I remonstrated, told them they never could stand it. It was hot, the hill steep. Mr. Day had once or twice said he “knew more about mountain traveling than any of us.” Five hundred feet were gained, some began to lag, the perspiration streamed, our green climbers pitched into the water, scarce as it was, rested, pushed on, some fell behind, and before we had ascended a thousand feet the intense heat, dense chaparral, and hard climbing told so fearfully that two gave out, drank up part of the water, rested, then went back. Averill went back with them, foreseeing a hard time, and fearing he would give out. The rest of us pushed on exultingly—hotter, more chaparral, greenies hotter, so they drank up the water.

At last the summit of Mount Choual, 3,400 feet, is reached. All are terribly thirsty, it is most intensely hot, all pant, all are dry. Here we lunch, for it is noon, in the heat, in the sun, of 136°, and no shade, no air, no water—and our lunch such as was fitting for a picnic. The butter had melted and streamed over everything—of course, we stood the best chance, being used to all kinds of fare.

Here two more gave out, as the hardest of the work was still ahead. Mr. Day’s “knowledge of mountain climbing” was hardly sufficient; he lay panting under the bushes and I feared for his safety. Four of us pushed on, intensely thirsty, but water lay ahead at the summit. We descended a few hundred feet through bad chaparral, then over a knob four or five hundred feet high, then descended again as much more. Here we got into a terrible chaparral. We toiled, tugged, worked, and lucky were those without instruments. We got so tired that, finding a shady spot under the dense brush, we lay down and rested or slept half an hour—quite refreshing. Strange, all dreamed of water. Our guide was hardy—he stood it well. Poor Wilson vowed that a “pleasure trip” would never get him on a mountain again. Our last ascent was a toilsome one, but soon after three o’clock we stood on the summit, 3,800 feet high, as nearly used up a set of men as you ever saw.

Water would have readily brought five dollars a quart, and sherry cobblers would have been above price—but there was no spring, no water. We must return; some feared they never could get back. I have not suffered so before with thirst—it was terrific. It was half past three when we got the instruments set; no one admired the landscape. One who gave out behind, pushed on and gained the summit; but, finding no water, all started back except Hoffmann and I, who stayed until after four o’clock taking our observations. Hoffmann’s eyes looked as sunken, his visage as haggard, as if he had been on hard fare for two weeks. I suspect I looked worse, for I had carried the barometer, level, etc. He carried the compass, tripod, and sketch book—but the fine view was left unsketched—only the topographical bearings and barometrical observations were taken. As before remarked, the rest started back, and straggled to the spring, one by one, haggard, used up, faint—some staggering, so faint—disgusted in general with mountain climbing.

Hoffmann and I took it back more slowly, often lying down to rest, and it was after sunset when we got back to the spring. Averill came up a few hundred feet and met us with a canteen of water. We soon drained the gallon between us, and were quite fresh when we reached the others. We soon saddled up, rode back by the bright light of the moon, and at half past nine were in camp. Supper, drink—two bottles of wine—and we sat and sang until eleven o’clock in the clear light of the moon, for it was Averill’s last night with us. I sent him to Monterey today to join Doctor Cooper, our naturalist.

Thus ended our trip. Had we the management of it all the suffering would have been avoided; as it was, it was a day of intense suffering. Today I am in camp, writing, packing specimens, etc.

New Almaden.

August 17.

It is a lovely Sunday—above 90° in the tent where I write, but less outside in the cool breeze, beneath the trees—there the air is delicious. Our camp seems small and quiet, but although my party is small, it is effective.

Yesterday (Saturday) we were up in good season, and Hoffmann and I rode to visit the other quicksilver mines of this vicinity. There are three mines within a region of six miles, all in the same ridge, which is about 1,700 feet high, lying parallel with the high chain of mountains behind, and separated from the Santa Clara Valley by a still lower chain of foothills.

We rode to the Enriquita Mine,9 about six miles from camp, by a trail over the hills. It is the poorest of the three, and lies about midway between the other two, the three being in a direct line. We introduced ourselves to the superintendent and engineer, Mr. Janin, who showed us every attention, going into the mine with us. It is much like New Almaden in character, but vastly poorer. Its owners are one set of disputants for the title of New Almaden also, so of course there is much feeling between the two mines. Four sets of claimants are lawing for New Almaden, and two more wait behind, to claim of these claimants should the latter be successful—a pretty “kettle of fish,” to be sure.

The mine of Enriquita has been going about two years, has its great works, deep cuts, long tunnels, furnaces, steam engine to work machinery, etc. Mr. Janin is a very young man, New Orleans birth, but has spent several years in Europe at mining schools, mostly at Freiburg in Saxony.10 He knew many of my friends, and we had a capital time.

The third mine, the Guadalupe, is two or three miles farther to the northwest. As he had never been in that, Mr. Janin offered to go with us, which he did, and introduced us to Doctor Mayhew. The mine is more rich, extensive, and profitable than the Enriquita, but vastly poorer than the New Almaden. It is mostly in a valley between the “mine ridge” and the main chain, and its workings extend down about 450 feet below the bottom of the valley. As it is so much lower it is much more wet and dirty than the other mines here. There are also workings in the hill, all of which we visited, spending some hours in climbing ladders, crawling through passages, threading tunnels, examining the character of the rock and ore everywhere.

We came out dirty, but were taken to Doctor Mayhew’s house, introduced to a lovely little wife, with two fine babies four months old. Doctor Mayhew is a rough Baltimore man, probably forty or forty-five, his wife a lovely girl of perhaps sixteen or seventeen. His story was brief but comprehensive: “Well, I wandered many years, concluded a year ago last spring that I ought to marry and settle, went home from Salt Lake, married, returned, and in nine months and two days was astonished with a pair of daughters. And here I have, in about a year and a half, traveled, stopped, married, settled, and have a smart and growing family—California is a prosperous state!”

His wife laughed heartily at her mistake, for seeing three men in red woolen shirts, belts, Spanish hats, saddles, spurs, etc., she had exclaimed, “There come some fine looking Mexicans!”

I loaded my saddlebags with specimens, returned to Enriquita, spent an hour or so more with Janin, then returned here at evening. We are having lovely moonlight nights now—cool, clear, bright. I am soory that I must so soon leave this place and the acquaintances I have made. We spent the evening at Mr. Day’s. It was pay day yesterday, and last night the town rang with the sound of violins, guitars, dancing, fandangos, singing, and mirth.

NOTES

1. The redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) is found as far south as the Santa Lucia Mountains, in Monterey County, and extends north barely beyond the Oregon boundary. In its natural state it is found nowhere else. The pine referred to here is the yellow pine (Pinus ponderosa); the fir is not a true fir, but the Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga taxifolia).

2. The big tree (Sequoia gigantea) is found in its natural state only in the Sierra Nevada.

3. This name, given in honor of Alexander Dallas Bache, Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey from 1843 to 1867, is no longer in use; the mountain is now called Loma Prieta.

4. Governor John G. Downey, born in Ireland, 1827, came to America in 1842 and to California in 1849. He was elected Lieutenant-Governor in 1859 and succeeded Governor Milton S. Latham when the latter resigned to become United States Senator in January, 1860. Downey was succeeded by Leland Stanford in January, 1862. His first wife, daughter of Don Rafael Guirado, was killed in a railroad accident in 1883. His sister, Eleanor, married Walter H. Harvey in 1858 (d. 1861) and Edward Martin in 1869; she died in San Francisco in 1928 at the age of 102 years. Another sister, Annie, married Peter Donahue in 1869; she died in 1896.

5. John Young, a native of Scotland, came to California in 1844 or 1845. He was a trader and master of vessels on the coast for a time. He died at San Francisco in 1864. He married a daughter of Robert Walkinshaw, a Scot who had been a resident of Mexico before coming to California in 1847. He managed the New Almaden mines prior to his return to Scotland in 1858.

6. Laurentine Hamilton, born at Seneca, N.Y., 1827, was educated at Hamilton College and at Auburn Theological Seminary, N.Y. He married Miss Isabella Mead, of Gorham, Me., and Ovid, N.Y. In 1855 he came to California as a missionary and went to the mining town of Columbia, where he built the Presbyterian Church that still stands. Later he became pastor of a church in San Jose until called in 1865 to the First Presbyterian Church in Oakland. He was an advanced liberal and was charged with heresy. Resigning, he established the Independent Presbyterian Church, which later was the Independent Church. On Easter Sunday, April 9, 1882, he dropped dead in his pulpit. His sermons and addresses were published in a volume entitled A Reasonable Christianity. Mount Hamilton, now famous as the site of Lick Observatory, bears his name. The little boy mentioned by Brewer was Edward H. Hamilton, a well-known journalist now (1930) living in San Francisco.

7. Sherman Day was graduated from Yale, A.B., 1826, and received also the degree of A.M. His father, Jeremiah Day (1773-1867), was president of Yale from 1817 to 1846. Sherman Day was born in New Haven, Connecticut, 1806; he died in Berkeley, California, 1884. After his graduation from Yale he lived in New York and Philadelphia for a time as a merchant. For several years he was in Ohio and Indiana as an engineer. In 1843 he published Historical Collections of the State of Pennsylvania. He came to California in 1849 and engaged in civil and mining engineering at San Jose, New Almaden, Folsom, and Oakland. In 1855 he made for the state a survey of wagon-road routes across the Sierra; he served in the State Senate, 1855-56; was United States Surveyor General for California, 1868-71; was one of the original trustees of the University of California, and for a time was Professor of Mine Construction and Surveying. He married Elizabeth Ann King, of Westfield, Mass., in 1832. The two daughters at New Almaden in 1861 were Harriet (Mrs. Charles Theodore Hart Palmer) and Jane Olivia (later Mrs. Henry Austin Palmer). The Miss Clark, of Folsom, was either Mary or Annie Clark; a sister, Harriet, had recently married Roger Sherman Day, son of Sherman Day. (Information from members of the Day family.)

8. The contest for title to the mines is summarized in Bancroft’s History of California, VI, 551.

9. This mine was opened in 1859. J. M. Hutchings, in Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California (1860), pp. 168-172, quotes an account of the dedication, which describes the naming of the mine for the little daughter of the manager, Mr. Laurencel, Henrietta (Spanish, Henriquita or Enriquita).

10. Louis Janin (1836-1914) was a native of New Orleans, where his father was a prominent member of the bar. After completing his sophomore year at Yale, in 1856, he went to Europe and studied mining engineering at Freiberg, Saxony, for three years. He also studied at the école des Mines, at Paris, before returning to America in 1861. His engagement as superintendent of the Enriquita Mine was a brief one. He was succeeded there by his younger brother, Henry, whose career up to this time closely paralleled his own. Louis Janin went to the Comstock mines in Nevada, where he advanced rapidly as a metallurgist, becoming superintendent of the Gould and Curry Company in 1864. After a period as manager of mines in Mexico he was employed for a year by the Japanese Government and then entered upon a long and distinguished practice as consulting engineer and mining expert with offices in San Francisco. During the last twenty years of his life he resided at Gaviota, California. (Biographical notice by R. W. Raymond in Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers for 1914, XLIX, 831.) It was through Louis Janin that Herbert Hoover received his start in the profession of mining engineering.

| Next: Chapter 4 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 2 |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/up_and_down_california/2-3.html