[click to enlarge]

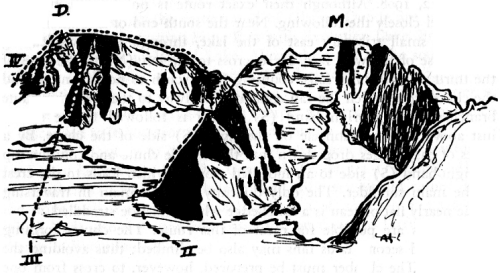

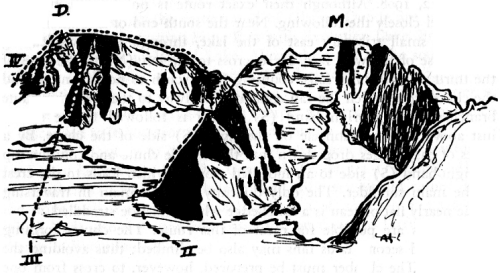

Sketch 15. Mounts Darwin and Mendel from the north. From left to right: Mount Darwin, Routes 4, 3, and 2; Mount Mendel.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Climber’s Guide to the High Sierra > The Evolution Region and the Black Divide >

Next: Palisades • Contents • Previous: LeConte Divide

WELL BACK in the central High Sierra is the Evolution region, where there are concentrated examples of almost every essential part of the High Sierra scene—cathedral-like Mount Huxley as an example of fine peak sculpture, the Enchanted Gorge for the majesty of exotic cliffs, Mount Goddard for superb views, and the Devil’s Crags to provide the challenge of jagged summits. This area has remained the most remote section of the entire crest, having no one-day route into its heart for pack animals and being hardly more accessible to knapsackers.

The Evolution region lies sixty miles southeast of Yosemite Park and twenty miles southwest of the town of Bishop. Almost all of the area is within the Kings Canyon National Park. The peaks are here divided geographically into four sections: (I) peaks of the crest, (2) peaks west of the crest, from north to south through the Goddard Divide, (3) peaks west of the crest and south of the Goddard Divide, and (4) peaks east of the crest. This, the natural grouping of the peaks, is used in describing them. The Mount Goddard quadrangle of the United States Geological Survey (either the 1937 or the 1951 editions) or the map accompanying Starr’s Guide should be referred to for cartographic detail.

Had sheepherders spent their hours keeping notes instead of sheep, more might be known with respect to who, in this as in many other parts of the Sierra, may have been the first white—or nearly white—mountaineer. The first known record of exploration is that of the California Geological Survey party, led by William H. Brewer, who approached the region from the north in August of 1864. Four members of this party attempted to climb Mount Goddard from a camp about twenty miles distant, and of these, two, including Richard Cotter, companion of Clarence King on that same year’s first ascent of Mount Tyndall, all but made it. In thirty-two hours, twenty-six without food, Cotter covered the forty-mile round trip, missing the summit by just 300 feet, according to Brewer’s journal.* Next of record is John Muir, who in about 1873, according to Francis P. Farquhar*, climbed the highest mountain at the head of the San Joaquin, probably Mount Darwin.

* Farquhar, Francis P. (ed.). Up and Down California in 1860-1864, the Journal of William H. Brewer. New Haven, 1930.

In 1879 Lil A. Winchell’s explorations took him to Mount Goddard, which he climbed with L. W. Davis; he returned to repeat the ascent in 1892. But the region remained virtually unknown and incompletely explored until July of 1895. Then, hoping to find a high mountain route between the Kings River Canyon and Yosemite Valley, Theodore S. Solomons and Ernest C. Bonner, left Florence Lake on a memorable expedition into the region.† Following sheep trials, they knapsacked up the south fork of the San Joaquin River and continued on into the Evolution Creek valley. At the head of what is now called Colby Meadow, a prominent mountain shaped like a sugarloaf suggested to Solomons a name, The Hermit, which he promptly bestowed. From here, also, he named the flat-topped Mount Darwin, Evolution Creek, Evolution Lake, and, to complete the homogeneity of the place names and to honor the respective philosophers, Mounts Huxley, Fiske, Spencer, Haeckel, and Wallace. Retracing their steps to the junction of Evolution Creek and the Goddard Canyon, the two men turned south and followed the canyon to its source, southwest of Mount Goddard, and made the third ascent of this peak. Dropping down the southeast side of the Goddard Divide, Solomons and Bonner entered the deep Enchanted Gorge, passing through a gateway formed by two black metamorphic peaks, which became Scylla and Charybdis, and descended Disappearing Creek, then Goddard Creek, and finally the Middle Fork of the Kings to Tehipite Valley. Thus they succeeded in finding a route from Yosemite to the Kings. The complete route has seldom been used since, but the place names Solomons left behind—and almost all in the region are his—are some of the most pleasing in the Sierra.

† Solomons, Theodore S. “Mount Goddard and Its Vicinity.” Appalachia, 8:41-57, 1896-1898.

The rest of the story follows a familiar pattern. Explorers had done their work. Then came the decades of scrambling, with the last of the important summits going down before the onslaught of members of high-mountain outings. As yet, relatively little roped climbing has been done in the region, except among the Devil’s Crags. A glance at the rugged terrain, however, is enough to convince a rock climber that there are still many excellent and difficult routes to be pioneered.

In the Evolution Region, as in nearly all parts of the High Sierra, there is an easy way to climb almost every peak. In general, the peaks on the crest are most easily climbed from the southwest, while the northeast sides present higher, more vertical faces for the rock-climber. The small glaciers of the region provide interesting routes for climbs of several peaks, such as Darwin, Goddard, and Mendel.

For the most part, the peaks of the crest are of granite. A substantial part of the region is composed of dark metamorphic rock, resembling the highly metamorphosed ancient lava of the Ritter Range. The Black Divide, Scylla, Charybdis, the Enchanted Gorge, Mounts McGee, Goddard, and the Black Giant are all, as many of the names imply, of dark rock, much of it beautifully sculptured. The beauty is not so apparent, however, to the rock-climber, who will find much of the metamorphic rock unsound and easily fractured. Chutes in the Devil’s Crags are particularly unsound and should be avoided during storms.

From the east. Bishop Pass, 11,989 (11,972n). At an elevation of 9,750 (9,755n) feet, leave the end of the road which follows the South Fork of Bishop Creek. From here a horse trail continues from South Lake over Bishop Pass into Dusy Basin, then down into LeConte Canyon. Excellent campsites are found in Dusy Basin and at Grouse and Little Pete meadows in LeConte Canyon.

From the east. Piute Pass 11,409 (11,423n). From the roadhead at North Lake the Piute Pass trail leads past Mount Humphreys and descends through Humphreys Basin and Hutchinson Meadow, following Piute Creek to its junction with the South Fork of the San Joaquin River. Here the Muir Trail may be followed southward into the Evolution Region. Campsites are both good and plentiful anywhere along Piute Creek or the upper reaches of the South Fork, particularly on Evolution Creek.

From the east. Lamarck Col, 13,000 (12,920+n). Lying 1/4 mile southeast of Mount Lamarck on the main Sierra crest, this high pass provides the most direct route for knapsackers into the Evolution Region. Because of the difficulties encountered by many climbers who did not follow the exact route, it will be described in detail. At the end of the road above North Lake leave the Piute Pass trail and follow a fork to the south (left) toward Grass Lake. Shortly after reaching the level of the first bench, on the northwest side of Grass Lake, the trail again divides. Here, follow the west (right) branch to Lower Lamarck Lake, skirting its southeastern end and continuing on westward toward Upper Lamarck Lake. Shortly before arriving at this latter lake, the trail forks into a western branch, which continues on to the lake, and a southern branch, which leads toward the spur forming the southern boundary of this upper lake basin. Follow the southern branch over this spur via a series of switch-backs, which ascend a north slope in a southerly direction reaching the first of several sand flats. (When crossing from west to east it is highly advisable to follow the side of the spur rather than to drop directly down to Upper Lamarck Lake.) Proceed in a southwesterly direction to the second sand flat, at which point the crest comes into view. Continue toward what appears to be a low gap to the southwest. On the north (right) side of this and somewhat beyond the low wall in which the gap is situated is a prominent butte with a large monolith. Continue up and through the gap, beyond which is a third sand flat which leads into the final cirque basin, after curving around the southern side of the butte with the monolith. At the head of this cirque valley is a tiny lake, to the south of which can be seen a jagged spire somewhat higher than its neighbors. To the east (left) of this spire is a low‘ notch, which leads to Bottleneck Lake. To the northwest (right) is a series of three or four notches in the arête leading up to Mount Lamarck. The first notch to the northwest (right) of the jagged spire is Lamarck Col, and it is best reached by passing to the south (left) of the lake, climbing between it and the tall spire, and then ascending directly to the col itself.

When the summit has been reached, the “trail,” now no more than a route, drops down toward the upper lakes of Darwin Canyon. After a descent of several hundred feet, it ends altogether save for an occasional duck. It is not imperative to follow the ducks, for any route may be followed over the talus and down the north side of Darwin Canyon. From the lower end of the canyon a ducked trail contours south to the Muir Trail at Evolution Lake. Fair campsites for small groups may be found around the lowest lake in Darwin Canyon. Excellent campsites are available on Darwin Bench halfway between the mouth of Darwin Canyon and Evolution Lake.

From the west. At Florence Lake, where the road from Fresno ends, a pack trail follows the South Fork of the San Joaquin River, joining the Muir Trail in Blaney Meadows; the Muir Trail ascends the South Fork into Goddard Canyon, and leads up Goddard Canyon to the Evolution Creek junction. The Muir Trail, following Evolution Creek, winds up a steep canyon, passes Evolution, McClure, and Colby meadows and continues on past Evolution Lake and over Muir Pass. With its vast supply of pasturage, wood, water, and scenery, Colby Meadow is one of the finest camping spots in the Sierra.

On the south shore of the large peninsula which enters Evolution Lake from the east and about one hundred yards from the trail there is a fairly well sheltered campsite for a small group, with feed for a few animals, firewood, and an excellent view of the southern half of the lake.

From the West. Hell-for-Sure Pass, 11,280+n. One of the first routes of access to the Evolution country, but now seldom used, is the trail from Dinkey, on the North Fork of the Kings, over Hell-for-Sure Pass, and down to Goddard Canyon. Knapsackers may easily travel directly up Goddard Canyon, taking the east branch for the Evolution Peaks or Muir Pass, or taking the main branch on south to Mount Goddard. Martha Lake, at the head of Goddard Canyon, is above timberline.

From Blackcap Basin it is readily possible to cross the saddle (11,850; 11,800+n) just north of Mount Reinstein. There is good camping at Lake 10,237 (10,212n), near the head of Goddard Creek.

From the South. Mather Pass (12,050). The John Muir Trail descends Palisade Creek to its junction with the Middle Fork of the Kings River. Just north of this junction is Grouse Meadow, a perfect little alpine valley. For climbs among the nearby Devil’s Crags there is an excellent site high up on the south fork of Rambaud Creek at about 10,200 feet.

The Goddard Divide. Muir Pass. The only trail that crosses the Goddard Divide is that over Muir Pass, 12,059 (11,955n). At the summit of the pass is the John Muir Memorial Shelter. Through the generosity of George Frederick Schwarz, the Sierra Club was able to build this stone hut in 1930. Since it is high above timberline, its fuel supply is strictly limited. Signs along the trail at the bottom of the pass advise the traveler of the last place to get wood before beginning to climb to the hut. Every extra branch that he can carry to the pass is just so much added insurance that the weary hiker, caught in a sudden summer storm, will find warmth in the hut.

Knapsackers may cross the Goddard Divide at the gap southwest of Wanda Lake. It is also practicable to go from Davis Lake to Martha Lake by a route west of Mount Goddard. A pass north of Davis Lake may be crossed to upper McGee Lake.

The Black Divide. Black Giant Pass, 12,200+ (12,200+n). Although not a pass of the Black Divide, Black Giant Pass offers the best approach to the Enchanted Gorge from Muir Pass. It is an easy, broad, knapsack pass, located about 1/2 mile due west of the Black Giant and about 1/4 mile north of a large lake at the headwaters of Disappearing Creek.

The Black Divide. Rambaud Pass, 11,500+ (11,553n). There is an old trail which ascends Rambaud Creek and crosses the Black Divide, dropping down its western slopes to Goddard Creek.

Glacier Divide. At the eastern end of Glacier Divide are two rocky knapsack passes connecting Piute Pass with Evolution Lake. From Piute Pass go southwest to Muriel Lake. Above the head of the southeastern tributary to this lake is a low notch, The Keyhole, 12,550 (12,560+n), so named because the climber may pass through it rather than over it. On the western side the slope drops sharply to a small lake basin, which is descended to its junction with Darwin Canyon. (See Sketch 14.)

Another tributary to Muriel Lake, which enters from the southwest, leads to a large basin filled by Goethe Lake, 11,511 (11,528n). Above the southeastern end of this lake a small tributary stream comes down the ridge wall from a small notch, Alpine Col, 12,200+ (12,320+n), which leads into the same lake basin and on down to Darwin Canyon, thence to Evolution Lake.

Peak 13,162 (13,160+n; 1.5 S of Piute Pass)

Class 2. First recorded ascent July 3, 1939, by James R. Harkins, Fred L. Toby, and Herbert L. Malcolm on a traverse of the crest from north to south; class 3 by this route, but estimated as class 2 from the head of the north fork of Lamarck Creek.

Mount Lamarck (13,450+; 13,417n)

Class 1. First ascent in the summer of 1925 by Norman Clyde, who found it an easy scramble from the south.

Peak 13,252 (13,248n; 1 NE of Mt. Darwin)

Class 2. First recorded ascent by Norman Clyde in the summer of 1925; however, he found a cairn.

Mount Darwin (13,841; 13,830n)

The broad, sandy, nivated summit table of Mount Darwin is a fascinating indication of what the ancient Sierra was like, before the great uplifts and the extensive glaciation. It is particularly odd that an unsteady-looking pinnacle, well detached from this summit plateau and southeast of it, is actually the highest point.

The first ascent on record was made by E. C. Andrews, Geological Survey of New South Wales, and Willard D. Johnson, of the United States Geological Survey.

Route 1. West wall. Class 3. First ascent by Andrews and Johnson, August 12, 1908. Although their exact route is not known, it seems to parallel closely the following. Near the south end of Evolution Lake ascend a small tributary east of the lake, through meadows leading to the base of the west face. Here, cross to the left (N) to the base of the third of three talus fans, counting from south to north, and ascend the chute from which the fan emanates. Midway to the crest this chute branches, and the right-hand (S) branch is followed to the saddle just above the first pinnacle on the right (S) side of the chute. By a series of easy ledges drop down into the middle chute and continue up its right-hand (S) side to an indented trough, which leads to the crest of the main shoulder. The only difficulty yet to remain in traversing to the nearly flat plateau is a knife-edge which must be straddled.

Variations are possible for most of this route. The chutes forming the first and second talus fans may also be climbed; thus avoiding the knife-edge. The climber must be prepared, however, to cross from one chute to another frequently. No one has yet determined which combination of chutes and traverses is best.

Route 2. Via glacier and west ridge. Class 3. First ascent by Robert M. Price and Peter Frandsen, August 21, 1921 (SCB, 1922, 284). Between Mounts Mendel and Darwin there is on the ridge a large notch with a smaller one about one hundred yards farther to the east. In an approach from the north via Darwin Canyon the glacier presents a problem. If weather is favorable and adequate equipment is available, the quickest route is directly up the glacier to the bergschrund, over it if possible, and on up to the smaller, eastern notch. The easier but longer route is to skirt the right (west) side of the glacier and then traverse above it from west to east to any of several routes to the small notch. The route then proceeds along the ridge to the summit plateau and thence to the higher, southeastern end.

Route 3. North face. Class 3 to 4. First ascent by David R. Brower and Hervey Voge, July 5, 1934. Two ribs or arêtes run down the north face, partly dividing the glacier. The east (left) side of the east rib, which lies one-quarter of a mile west of the northeast ridge, is ascended a short distance over talus and snow. The route then goes up onto the rib itself and ascends, via easy ledges, up to the point where the rib merges with the face. Here a moderate pitch is passed by a crack to the left (east), and the final climb to the summit may be made via a small chimney having an overhanging south wall and containing several large, loose blocks. (See Sketch 15.)

[click to enlarge] Sketch 15. Mounts Darwin and Mendel from the north. From left to right: Mount Darwin, Routes 4, 3, and 2; Mount Mendel. |

Route 4. Northeast ridge. Class 4. First ascent in 1945 by Austin, Pabst and Wilts who climbed some 500 feet of difficult class 4 terrain to the summit. (See Sketch 15.)

Route 5. East face. Class 3. Climbed from Blue Heaven Lake (above Midnight Lake) by members of the 1950 Base Camp. Above the glacier on the east side a snow tongue and rock rib were climbed to the summit plateau.

Summit Pinnacle. Class 4. The detached summit pinnacle was first climbed by E. C. Andrews on August 12, 1908; he descended into the chimney east of the arête between the summit and the pinnacle, thence reaching the top by means of a “monstrous icicle,” referring doubtlessly to the snow tongue which lies in the chimney well into the summer. Ascent of this chimney fortunately does not depend upon the existence of the icicle. It is a rock scramble permitting several variations, exposed just enough to warrant a belay for the unsteady.

Peak 13,332 (13,280+n; 3/4 SE of Mt. Darwin)

Class 3. Climbed on July 19, 1933, by Glen Dawson, Neil Ruge, and Bala Ballantine. There was no evidence of previous ascent.

Mount Haeckel (13,422; 13,435n)

Route 1. West shoulder. Class 2. On July 14, 1920, a party of nine climbers, led by Walter L. Huber, left Evolution Lake, going around the west shoulder of Mount Spencer, and climbed into a small basin between Mounts Spencer and Huxley (SCB, 1921, 144). From this point they crossed along the left of the basin and then ascended a chute to the top of a ridge which joined the crest just south of the summit. The only serious obstacle remaining, a vertical face of 30-40 feet, was surmounted with the help of a number of excellent hand-holds.

Route 2. South ridge. Class 2. First ascent by Edward O. Allen, Francis E. Crofts, and Olcott Haskell, also on July 14, 1920. From the small basin between Mounts Spencer and Huxley, proceed directly across this amphitheater, climb to the saddle between Mounts Haeckel and Wallace, and traverse the many sawteeth to the summit. Allen, Crofts, and Haskell were quite surprised to find that they had been beaten to the summit by a matter of minutes. Yet, still greater was their surprise on learning that they had not, as they had intended, climbed Mount Darwin.Route 3. North face. Class 3. The first ascent was made on July 20, 1933, by Jack Riegelhuth, who climbed up the northwest chimney and then the north face to the top.

Route 4. Northeast ridge. Class 2. On August 8, 1935, Merton Brown, O. H. Taylor, and Angus E. Taylor reached the larger of two arêtes on the northeast side of the summit. Here Brown climbed the slabs to the lower and then the higher summit. The Taylors ascended the arête, traversing to the crest at about the point where the west shoulder joins it.

Mount Wallace (13,328; 13,377n)

On an early edition of the Mount Goddard quadrangle, Mount Wallace was erroneously placed upon the 13,701 (Mount Mendel, 13,691n) foot peak northwest of Mount Darwin. On the 1937 edition it is still, according to Solomons who named it, incorrectly marked as the peak at the junction of the Goddard Divide and the crest. The true Mount Wallace is peak 13,328 (13,377n), on the crest about one-half mile north of the junction of the Goddard Divide and the crest.

Class 2. First ascent by Theodore S. Solomons, July 16, 1895. From the amphitheater west of the summit, climb up a rock-filled chute that leads to a splintered wall whose highest point is the summit. A class 3 route leads up the north ridge from the east.

Clyde Spires (13,300+; 13,267n)

Between Mounts Wallace and Powell on the main crest are two small granite spires. The north spire (13,267n) was first climbed on July 22, 1933, by Norman Clyde, Jules Eichorn, Theodore Waller, Helen LeConte, Julie Mortimer, Dorothy Baird, and John D. Forbes. The south spire was ascended the same day by Clyde, Eichorn and Waller and proved to be a difficult slab climb. The spires were named after the party’s leader.

Mount Powell (13,361; 13,360+n)

Route 1. South plateau. Class 2. First ascent August 1, 1925, by Walter L. Huber and James Rennie. From Helen Lake climb an intervening ridge of about 12,200 feet, and drop down several hundred feet into a small cirque. Then climb the ridge just south of the summit and follow the long, barren plateau to the top. The final peak is a huge summit block where “a careless step might result in a drop to the glacial ice far below, under the north face.”

Route 2. Northwest chute. Class 3. First ascent by Norman Clyde on June 29, 1931, who described it as “an interesting climb from the northwest.” Members of the 1950 Sierra Club Base Camp proceeded past Moonlight Lake and ascended snow patches between the Powell ridge and the eastern lateral moraine. They crossed the snow below the flat turret which marks the northeast end of Mount Powell and climbed up the southernmost of two large, parallel cracks in the west wall for twenty feet, after which they climbed the face of the wall itself toward the south.

Route 3. East ridge. Class 3. First ascent by Norman Clyde (date unknown) who climbed from Blue Lake on the middle fork of Bishop Creek via the col between Mounts Powell and Thompson.

Mount Thompson (13,494; 13,480+n)

The first ascent of this peak, which marks the junction of Thompson Ridge with the main crest, was made by Clarence H. Rhudy and H. F. Katzenbach in 1909. Their route is unrecorded. Several routes have since been used.

Route 1. Northwest face. Class 3. First ascent, June 30, 1931, by Norman Clyde.

Route 2. Southwest face. Class 2. First ascent by Jack Sturgeon on August 14, 1939. Ascend via some steep slopes and a narrow chute on the face itself.

Mount Gilbert (13,232; 13,103n

Although correctly marked on the 1937 edition, Mount Gilbert has been incorrectly labeled on the 1951 edition of the Goddard quadrangle; it is actually Peak 13,103n which is 3/8 mile west of the incorrectly labeled summit.

Class 2. First ascent by Norman Clyde on September 15, 1928. Clyde desk ribed it as an “easy ascent except for a chute which may at times be icy; no cairn.” On August 14, 1939, Jack Sturgeon followed the crest and climbed it via the southeast slopes, reporting a cairn but no record.

Mount Johnson (12,850; 12,868n)

Class 2. Jack Sturgeon, who ascended the peak on August 14, 1939, by way of the western arête, reported that it had previously been climbed twice by Norman Clyde.

Mount Goode (13,068; 13,092n)

Class 1. The first recorded ascent, via the southeast face, was made by Chester Versteeg, July 16, 1939; a cairn was found but no record. An ascent of the south ridge was made by Jack Sturgeon on August 12, 1939, while traversing the crest from Bishop Pass to Mount Thompson.

Peak 12,903 (12,916n; 1/2 S of Mount Goode)

Class 1. On July 12, 1939, Chester Versteeg made the first recorded ascent of the higher summit. Norman Clyde, in 1936, climbed the lower but more difficult summit, which Versteeg considered to be class 3.

Peak 12,026 (12,045n; 1.5 SW of Hutchinson Meadow)

Class 2. The first ascent of this northernmost peak of the Glacier Divide was made on July 4, 1939, by Marion Abbott and Scott Smith.

Peak 12,592 (12,582n; 2.2 S of Hutchinson Meadow)

Class 2. First ascent on July 14, 1933, by Hans Helmut Leschke, Dr. Hans Leschke, and Helen LeConte from the north.

Peak 12,251 (12,241n; 1.5 NE of Evolution Meadow)

Class 2. Weldon Heald and Alden Smith made the first ascent on July 5, 1939.

Peak 12,486 (12,498n; 1 S of Golden Trout Lake)

Class 3. First ascent by Glen Dawson and Neil Ruge on July 11, 1933.

Peak 12,961 (12,971n; 1.8 S of Golden Trout Lake)

Class 2. Northwest of the Goethe Glacier and lying on the crest of the Glacier Divide, this peak was first climbed by R. S. Fink on July 25, 1942. The second ascent was on August 29, 1942, by August Frugé, Neal Harlow, and William A. Sherrill, who climbed from McClure Meadow to the saddle between Peak 12,961 (12,971n) and Peak 13,250+ (13,240+n) to the southeast and thence directly to the summit.

Muriel Peak (12,951; 12,942n)

Class 2. First ascent on July 8, 1933, by Hervey Voge, who described it as “an easy rock-climb from the west.”

Mount Goethe (13,277; 13,240+n)

Class 1. First recorded ascent by David R. Brower and George Rockwood on July 6, 1933. This, the highest point on the Glacier Divide, is an easy ascent from the east.

Peak 12,741 (12,720+n; 1 W of Mt. Lamarck)

Class 2. First ascent July 5, 1934, by David R. Brower, who climbed the south side and descended the west ridge. There is some scrambling among the large blocks of the summit ridge. Brower could not determine which end of the ridge was higher.

Ridge 11,922 (12,355n; 1.5 NE of Colby Meadow)

First ascent July 29, 1941, by members of the Sierra Club knapsack trip.

Mount Mendel (13,701; 13,691n)

For many years this peak was erroneously labeled Mount Wallace on the topographic map. On the 1937 edition it bore only the elevation and soon acquired among climbers the rather inelegant title of “Ex-Wallace.” On the 1951 edition it has at last been named correctly and thus assumes its rightful place among the great Sierra summits.

Class 3. The first recorded ascent was by Jules Eichorn, Glen Dawson, and John Olmstead on July 18, 1930; they found a cairn. The chimney by which they ascended was considered more difficult than the climbing on Darwin. It is quite possible that the first ascent was made in error by climbers, seeking the summit of Darwin, who started climbing, as has so often been done, too far north along the shores of Evolution Lake.

The easiest route up Mount Mendel is readily apparent from The Hermit. About 400 yards along the Muir Trail south of the peninsula jutting into the lower end of Evolution Lake, a massive buttress of glaciated granite descends from the peak, in contrast to the extensive accumulation of talus bordering the lower half of the east shore. Ascend this buttress for 1,500 feet, diagonally up and southward, until the glaciated granite gives way to the broken rock of the summit mass. Then continue upward by crossing right (SE) to a talus fan, the first fan southeast of the buttress, and ascend this fan into the chute from which it emanates, keeping in the north branch of the chute, to the notch at its head. Thence, traverse north along the broken and serrated ridge to the summit.

Two of the most spectacular snow couloirs in the Sierra descend the north face of Mount Mendel. So far as known, these have not been attempted. Climbers who would explore them are urged to investigate i hem cautiously from Mount Lamarck to the north or from Darwin Canyon at the base.

The Hermit (12,352; 12,360n)

The cleanly sculptured granite of The Hermit culminates in an inviting summit that dominates the view from Colby Meadow. It was first ascended by George R. Bunn on July 28, 1924, but his route is unrecorded.

The final summit monolith was ascended in 1925 by James Rennie and Norman Clyde. Bunn had declared that the “20-foot summit slab” was unclimbable. However, it was climbed by sixty-five persons in three days in July, 1939. Because of the exposure, a rope is recommended for the final pitch. A shoulder stand is usually used and dexterity is required.

Route 1. From Evolution Lake. Class 2. The easiest and most often used route is to cross just below Evolution Lake, contour to the base of the peak, and climb the eastern talus chute to the notch just south of the summit, traversing from there to the summit. From the base of the peak on the east side it is also fairly simple to work out on the more exposed face and thence directly to the summit.

Route 2. From McGee Canyon. Class 2. Ascend McGee Canyon to about 10,400 feet and proceed east up the first tributary to the small lake that feeds it; thence, ascend over talus and scree to the top of the chute heading in the notch south of the summit, from which point proceed as in Route 1. Special care must be taken to avoid loosening the rocks in the chute.

Route 3. North ridge. Class 3. First ascent on July 9, 1936, by Richard G. Johnson and Peter Grubb. From Colby Meadow ascend through forest and over easy, open granite to a shelf on the north shoulder, usually sheltering a snow bank, just beneath the high-angle granite slabs of the final 1,000 feet of the summit. From here traverse to the left (E) under the cliffs and proceed diagonally up and westward over granite slabs, now more broken and at a lower angle, to the final summit pitch which must be reached by traversing to the south of the peak, 25 feet below the summit.

Route 4. Northwest face. Class 3. First ascent July 9, 1939, by Harriet Parsons, Madi Bacon, and Maxine Cushing. Follow Route 3 to the snow-bearing shelf. Here a broad ledge extends up and around the west face to a chute leading back to the shoulder, but above the cliffs that shelter the snow. Continue over the steep but broken ridge to the summit, as in Route 3.

Peak 12,341 (12,35012; 1/2 SE of The Hermit)

This peak erroneously bore the name of The Hermit on an earlier edition of the map. It was first climbed by Dr. Grove Karl Gilbert and Mr. Kanawyer, the packer, in July, 1904. It is a class 1 climb by either the southeast ridge or from the saddle on the northwest ridge.

Mount Spencer (12,428; 12440+n)

Class 1. First climbed by Robert M. Price, George J. Young, H. W. Hill, and Peter Frandsen on August 20, 1921. About one-half mile above Evolution Lake ascend one and a half miles east along a tributary creek, reaching lake 11,592n. Climb over broken granite and talus to the east saddle of the peak, thence westward and up to the summit. The saddle is just as easily reached from the lake basin east of Sapphire Lake.

Mount Fiske (13,560; 13,524n)

Named in 1895 by Theodore S. Solomons for John Fiske, historian and philosopher, this peak was first climbed by Charles Norman Fiske, John N. Fiske, Stephen B. Fiske, and Frederick Kellet on August so, 1922 (SCB, 1923, 417).

Route 1. Southeast ridge. Class 1. First ascent by the above party on August 10, 1922. From Muir Pass contour at about 12,000 feet around the southeast side of Peak 13,223 (13,231n), and then drop down about 200 feet to the small lake to the northwest of Helen Lake. A steady climb then leads to the southeast peak, whence the ridge may be followed to the summit.

Route 2. Southwest ridge. Class 2. First ascent on August 18, 1939, by jack Sturgeon, who traversed from Peak 13,233 (13,231n) and the basin to the south, ascending by way of the southwest arête. The southwest saddle is easily accessible from the group of lakes, nestled between Mounts Fiske and Huxley, which drain into Sapphire Lake. The nivated slope east of this ridge provides a class 1 route.

Mount Huxley (13,124; 13,117n)

Class 2. First ascent by Norman Clyde on July 15, 1920. From the trail on the first bench above Sapphire Lake, ascend the southern side of the western shoulder until the angle steepens appreciably; then continue up the shallow chute, which empties almost on the shoulder itself, to the slabs and large blocks of the sharp summit arête. Descent of the southwest chute and face may require the use of rope.

Peak 13,223 (13,231n; 1 N of Muir Pass)

Class 1. First ascent in 1926 by Nathaniel Goodrich and Marjory Hurd. This is an easy traverse from either Muir Pass or Mount Huxley. The best opportunities for rock-climbing are found on the east face and in the small cirque to the north of the summit, between Mounts Huxley and Fiske, but no climbing has yet been reported there.

Peak 12,800+ (12,800+n; 3/4 W of Muir Pass)

First ascent by Jack W. Sturgeon in 1939. Route and class unknown.

Peak 13,012 (13,016n; 1/2 SW of Muir Pass)

Class 2. The first ascent was made by M. H. Pramme and T. F. Harms on August 12, 1929. It is an easy climb directly from Muir Pass via the northeast shoulder or by the snow chute which heads in very loose rock just under the flat summit. By way of the southwest ridge it is a class 1 climb, but the ridge itself is remote. The summit affords a striking view of Scylla, Charybdis, and the Ionian Basin.

Peak 13,070 (13,081n; 1 S of Wanda Lake)

Class 1. First ascent by Jack Sturgeon on August 16, 1939. Held to be an easy climb by the northeast ridge or almost anywhere on the southern or western slopes.

Mount Goddard (13,555; 13,568n)

The early history of the Evolution Region is, in many respects, the early history of Mount Goddard. Many were the explorers who were enamoured of its summit, and for good reason: it was not only one of the highest summits in the range, but also it was well isolated, distinctly set off to the west of the crest, and could promise a unique view and admirable triangulation station for topographic mapping. Members of the Whitney Survey viewed the peak from far to the south in 1864, named it in honor of civil-engineer George Henry Goddard, attempted to climb it twice, and estimated the height to be 14,000 feet. It was not climbed, however, until fifteen years later, when, on September 23, 1879, Lil A. Winchell and Louis W. Davis made the first ascent.

Routes. There are class 1 routes up the talus of the southwest ridge from Martha Lake, and up the east slopes rising from the head of the northernmost tributary to Goddard Creek. Neither of these routes is readily accessible, however, from the most frequented trails. Walter Starr, Jr., has given a detailed description of the class 2 approach from the Muir Trail, which is essentially as follows:

At the lower end of Wanda Lake, ford the outlet, cross the saddle to the southwest at its lowest point, and descend into the rocky basin beyond. Continue almost due south across the basin, fording several small streams some distance above Davis Lake, and proceed toward the very steep spur which ascends from the floor of the basin southward to the crest of the Goddard Divide. Rock-climbers may proceed straight up the very steep top of the ridge from the floor of the basin. Those who prefer snow climbing may work their way onto the buttress higher up from the snow on the right. A short distance below the crest, where the buttress becomes almost perpendicular, a ledge leads around the left side, above the long snowfield, and comes out on the crest to the left of the point at the top of the buttress. From here a long talus slope leads up the crest to the summit. There is a double summit, the farther peak being higher.

Peak 12,908 (12,913n; 1 N of Mt. Goddard)

First ascent by R. S. Fink on July 27, 1941, by an unrecorded route. Second ascent on September 2, 1942, by August Frugé, William A. Sherrill, and Neal Harlow whose route was as follows:

Class 3 to 4. After leaving the Muir Trail at the outlet of Wanda Lake, proceed over the low saddle to the southwest and thence across the large basin toward the ridge connecting Peak 12,908 (12,913n) with the crest of the Goddard Divide. Ascend this ridge via the steep, blunt buttress to the southeast of the summit. Then follow the ridge, passing to the right (E) of a large pinnacle and then out onto the left (W) side of the ridge, traversing onto the steep south face of the summit mass itself. A narrow chimney then leads up to several chutes which may be followed to the summit.

Peak 12,279 (12,290n; 1 NW of Wanda Lake)

Class 1. First ascent by Kenneth Adam, 1933. This peak may be easily climbed from the north or east.

Mount McGee (12,966; 12,969n)

Mount McGee dominates the westerly panorama from Muir Pass. Sharply sculptured, dark with metamorphic rock, it is situated just far enough from the Muir Trail to have discouraged most climbers who might have liked to reach the summit. It may be approached from Goddard Canyon, Colby Meadow, or from Wanda and Davis lakes. It was first climbed July It, 1923, by Roger N. Burnham, Robert E. Brownlee, Ralph H. Brandt, and Leonard Keeler; their route is unrecorded.

Route 1. North chute. Class 4. First ascent by Glen Dawson, Charles Dodge, Jules M. Eichorn, and John Olmstead on July 16, 1930. From Colby Meadow proceed up McGee Canyon directly toward the summit, turning southwest when past timberline to climb over moraine and talus toward a spur at the base of the west peak, which resembles a massive inverted shield. Ascend the ridge that circles west of the residual glacier and which deflects westward the drainage from the mouth of the steep snow-chute cleft in the north face of the peak, but well to the west of its center. It is usually possible to ascend this chute along the edge, where the snow has melted back from the rock wall. The last 800 feet of the chute is exposed enough to merit use of a rope for safety. From the notch at the top of the chute, proceed east along the well-broken ridge to the summit.

Route 2. West face. Class 2. First ascent by Glen Dawson, Neil Ruge, and Bala Ballantine on July 17, 1933. From Goddard Canyon ascend the east fork of North Goddard Creek to about 11,000 feet. Proceed northwest to the base of the west face and ascend the talus to the summit of the west peak, traversing from there into the notch at the head of Route 1.

Route 3. South chute. Class 1. (Probably the route of the first ascent.) From the lower end of Davis Lake ascend the broad fan of scree and talus to the prominent chute ending in the notch between the west and east summits. Ascend the scree in this chute to the notch and proceed east to the summit. The sliding nature of the scree makes this route a bit disagreeable as a means of ascent.

Peter Peak (12,514; 12,543n)

Class 2. First ascent on July 11, 1936, by Peter Grubb and Richard G. Johnson. Ascend to the northeast notch from the head of McGee Canyon, and climb the ridge to the summit. Grubb and Johnson also climbed the eastern buttress of the peak when making the first ascent. The metamorphic rock of the peak, and particularly of the chute leading to the notch, is quite unsound. One must “hold the mountain together with one hand while he climbs it with the other.”

Peak 12,200 (12,258n; 1/4 NE of Peter Peak)

First ascent July 11, 1936, by Peter Grubb and Richard G. Johnson.

Peak 12,407 (12400+n; 3/4 SE of Emerald Peak)

First ascent July 9, 1939, by Alden Smith and Grace Nelson.

Emerald Peak (12,517; 12,546n)

Class 2. First ascent made by Norman Clyde, Julie Mortimer, and Eleanor Bartlett, August 8, 1925. From Evolution Meadow ascend the steep south wall of the canyon and continue over the gradual slope above to the north base of Peak 11,764. It is perfectly feasible to climb this peak first, traversing the northwest ridge of Emerald Peak to its summit. It is much easier, however, to contour a mile at 11,000 feet (timberline) until almost due west of the peak, thence climbing over talus and nivated slope to the top.

Peak 11,764 (11,767n; 1 NW of Emerald Peak)

First ascent in 1925 by Norman Clyde; see Emerald Peak above.

South of the Goddard Divide, between LeConte Canyon and the White Divide, is the wildest part of the High Sierra. Perhaps no more than a dozen parties have been through the Enchanted Gorge since its discovery. Of the Ragged Spur peaks, only Scylla is known to have been climbed and that but once. Place names are rather far between. From the old map it is apparent that the Geological Survey parties were not too familiar with the topography. Lack of trails, rugged terrain, high altitude and low timberline, remoteness, and the lack of any great number of mountaineers who would prefer to cope with these conditions—all this has contributed to ‘the final result: a knapsacker’s wilderness, as black, ragged, and enchanting as its place names.

Peak 12,700+ (12,760+n; 3/4 SW of Mt. Gilbert)

First ascent by Jack W. Sturgeon in 1939. Route and class of climb unreported.

Peak 12,100 (12,148n; 1/2 SW of Mt. Johnson)

First ascent made in 1939 by Jack W. Sturgeon via unreported route.

Peak 12,700+ (12,760+n; 3/4 S of Muir Pass)

First ascent by Jack W. Sturgeon in 1939. Class and route unknown.

Scylla (12,943; 12,939n)

Class 1. First ascent by David R. Brower and Hervey Voge on July 2, 1934. From Muir Pass, cross Black Giant Pass and contour at an elevation of about 12,000 feet along the north slope of the Ionian Basin, past Lake 12,002 (11,824n) to the lake just north of Scylla. From here the route to the summit is an easy scramble, the best rock-climbing near the peak being found on the sharp crags to the east.

Charybdis (13,077; 13,091n)

Class 2. First ascent on July 7, 1931, by Anna and John R. Dempster. Cross Black Giant Pass to the large lake at the head of the east fork of Disappearing Creek and follow up the northeast ridge, going somewhat to the south of the ridge at times. There are several chutes on the north face, any of which may be used.

Peak 12,818 (12,800+n; 1 E of Muir Pass)

Class 1. First ascent by Kenneth Davis and John U. White on August 3, 1938, from Muir Pass via the west slope.

Black Giant (13,312; 13,330n)

Class 1. First ascent by George R. Davis in 1905. Along the western side the climb is little more than a rock scramble. On the eastern approaches, however, the whole ridge is sharply broken off. Any ascent from this side would be considerably more difficult.

Peak 13,046n (1.5 E of Charybdis)

No records are available. The name Mt. Locker has been suggested for this peak to commemorate Charles Bays Locker who was killed while descending with three companions from a first ascent of a small peak one-half mile east, Peak 12,360+n.

Peak 13,260 (13,271n; 2 SE of Charybdis)

Route 1. North ridge. Class 3. First ascent by Charles Bays Locker, Karl Hufbauer and Alfred Elkin on July 23, 1951. From the northwest, climb to the saddle between peaks 13,260 (13,271n) and 13,000+ (13,046n) to the north, and thence along the ridge to the south, keeping 50-100 feet below the top of the crest. The final summit climb is up the north side of the 150-foot snow chute which lies just below the summit on the west face.

Route 2. Southeast ridge. Class unreported. First ascent by Charles Bays Locker, Don Albright, Gary Hufbauer, and Karl Hufbauer on July 15, 1952. From the small lake 3/4 mile to the southeast of the summit, proceed up the west (left) side of the southeast ridge, following it to the summit.

Peak 12,114 (12,1250; i W of Langille Peak)

Class 2. First ascent by George R. Davis and George W. Hoop on August 19, 1907. This is a class 2 climb by either the southwest ridge or on a traverse from Langille Peak.

Langille Peak (11,981; 11,991n)

Class 3. The first ascent of this magnificent example of finely sculptured, gleaming granite was accomplished in August 1926 by Nathaniel L. Goodrich, Marjory Hurd, and Dean Peabody, Jr. The route of their ascent is unrecorded, possibly via the west ridge. They descended by way of the south face, a vast glaciated granite apron of polished smoothness (class 3). The first ascent by this latter route was made by Glen Warner and Suzanne Burgess on August 5, 1941. From LeConte Canyon ascend the tributary opposite the Dusy Branch and climb the cirque wall just north of the prominent waterfall above 11,000 feet. Traverse to the north onto the west ridge, and follow this to the summit.

Peak 12,699 (12,652n; 1.3 S of Mt. Goode)

Class 1. First recorded ascent by Chester Versteeg on July 14, 1939. An easy climb either by the southeast ridge or from Dusy Basin on the south.

Peak 12,566 (12,520+n; 2.2 E of Charybdis)

Class 2. First ascent August 5, 1941, by Glen Warner and Suzanne Burgess. From LeConte Canyon ascend the tributary opposite Dusy Branch to 10,500 feet, climb the chute leading to the notch just south of the summit. A narrow snow chute provides a class 3 route up the north face.

Peak 12,400+ (12,483n; 1.5 N of Ladder Lake)

Class 2. First ascent July 13, 1952, by Charles Bays Locker, Karl Hufbauer, and Don Albright. A difficult class 2 climb from Ladder Lake via the south arête.

Peak 12,935 (12,920+n; 1 SE of Charybdis)

No records are available.

The Citadel (11,700+; 15,744n; 1.5 NW of Grouse Meadows)

Route 1. West ridge. Class 2. First ascent on June 24, 1951, by Richard Searle and William Wirt. Proceed from Ladder Lake directly up the west ridge to the summit.

Route 2. Northeast face. Class 4. First ascent by Donald Goodrich and Robert Means on June 24, 1951, arriving on top several hours after the party of the first route. Ascend the northeast face via several gullies and chutes to the summit ridge, climbing southwest along this ridge over the subsidiary East Peak and traversing along the ridge to the higher West Peak.

Route 3. North wall. Class 4. First ascent by Charles Bays Locker, R. J. McKenna, S. Hall, D. E. Albright, and Karl G. Hufbauer. Ascend to the base of the northwest buttress from the eastern end of Ladder Lake. Climb up the first chute on the northwest side of the peak. From the top of the chute proceed along the ridge to the left (E) directly to the summit.

Peak 12,015 (12,009n; 1.5 W of Grouse Meadow)

Route 1. Southeast arête. Class 2. First ascent on August 9, 1934, by H. B. Blanks and B. S. Kaiser who climbed from the Rambaud Lake Basin via the southeast arête. This party made a complete traverse of the ridge from east to west.

Route 2. North ridge. Class 2. First ascent by this route by Charles Bays Locker, Donald Albright, Gary Hufbauer, and Karl Hufbauer. Climb from Laddei Lake in a southeasterly direction to the north ridge and follow it to the summit; no particular obstacles are encountered.

The western summit of this peak (approx. 12,000) was also climbed by both parties and is a class 1 traverse from the eastern summit.

Peak 12,400+ (12,425n; 1 SW of Ladder Lake)

Class 3. First ascent on August 9, 1934, by H. B. Blanks and B. S. Kaiser who traversed the ridge from the east.

Peak 12,767 (12,760+n; 1 NW of Wheel Mtn.)

First ascent by Charles Bays Locker, Donald Albright, and Gary and Karl Hufbauer, July 15, 1952. Class 3 from the crest of the Black Divide,

Peak 12,400+ (12400+n; 1/4 SW of Peak 12,425n)

Class 2. First ascent on August 9, 1934, by H. B. Blanks and B. S. Kaiser on a traverse from the ridge to the east.

Wheel Mountain (12,778; 12,781n)

Class 2. First ascent on July 26, 1933, by Marjory Bridge, John Cahill, Lewis F. Clark, and John Poindexter. Climb from the lakes at the Bead of Rambaud Creek to the basin south of the peak. Traverse the ridge and plateau on the south and west. Ascend the ridge on the northwest to the summit. Descent is possible by means of two steep gullies on the south face.

Rambaud Peak (11,023; 11,040+n)

Class 2. First ascent in 1925 by Albert Tachet and Ruth Prager. This is a scramble from Rambaud Creek campsites to the north, and is an excellent point from which to study the Devil’s Crags.

Devil’s Crags (12,612—11,000; 12,600+n—11,240+)

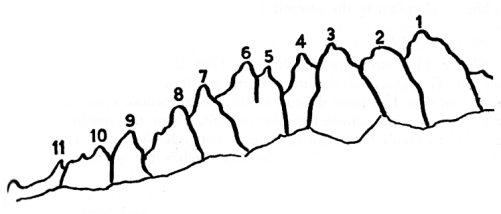

The Devil’s Crags are about two miles southwest of Grouse Meadow and form the southern end of the Black Divide. They are slightly over mile in length, have a northwest-southeast trend, and the highest crag is at the northern end. Although several systems of numbering have been employed, the system here used numbers only those crags which rise 150 feet or more above their notches (see Sketch 16). Since this

[click to enlarge] Sketch 16. The Devil’s Crags from Rambaud Peak. |

Highest (12,612; 12,600+n)

Route 1. Southwest face. Class 3. First ascent made by Charles Michael on July 21, 1913. Two chutes on the southwest face cross each other forming an “X.” Climb the left (northwest) chute to the junction, where the most direct route is to continue on straight across, following the upper right-hand chute nearly to the summit and then swinging to the left to the arête and following it to the top. An alternate and less difficult route is to take the upper left-hand chute at the intersection, following it to the arête, and climbing along the arête to the summit.

Route 2. Northwest arête. Class 3. First ascent by Jules Eichorn, Helen LeConte, and Alfred Weiler on July 25, 1933. Follow the crest of the northwest arête to the summit.

Route 3. Northeast face. Class 4. First ascent by Raffi Bedayan, Kenneth Davis, and Jack Riegelhuth on August 5, 1938. From the upper end of the lake at 10,450 feet on Rambaud Creek, proceed southeast half a mile to the notch just under and northeast of the face; this is the roping-up point. Traverse to the right (northwest) and up over somewhat loose rocks of a delicate pitch to the chute marking the middle of the face, planning the traverse so as to end well above the overhanging lower portion of the chute. Ascend this chute toward the summit over rock that is fairly sound. Belay positions are good for the most part. When 35 feet below the summit, cross to the north wall of the chute, ascend a high-angle pitch to the summit ridge, and scramble to the top.

Crag 2 (12,350)

Class 4. First ascent by Jules Eichorn, Glen Dawson, and Ted Waller on July 26, 1933. Climb the first chimney south of the main peak on the northeast side. It is most difficult in the lower portion. From the notch the ridge is easily climbed to the summit. From the southwest it is possible to climb the chute that heads between Crag 2 and the subsidiary crag to the north. From the notch follow the arête.

Crag 3 (12,350)

First ascent by David R. Brower, Hervey Voge, and Norman Clyde on June 24, 1934.

Route 1. From the northeast. Class 4. Climb the northeast chute between Crags 2 and 3, remaining on the floor of the chute and passing under the huge chockstone. From the notch climb the first pitch by the left side of the broken face. Contour out and up on the broad, sloping ledge on the north face to the north arête. Climb the left side of this to the northwest arête, and thence to the summit. With little more difficulty the northwest arête may be followed from the notch.

Route 2. Traverse. Class 4. The southeast arête may be descended 250 feet without too much difficulty. Descend a sloping, broken ledge heading on the east side of the peak. Follow this down and to the south, traversing easterly to a very broad shelf when the angle becomes too severe. Climb down an additional 60 feet just west of the southeast arête. Ensuing overhangs will suggest roping down into the notch between Crags 3 and 4. Descend via the southwest chute. If this route is used for an ascent, pitons are necessary for spfety while climbing the largest overhang, 100 feet above the notch.

Route 3. From the southwest. Class 3. Climb the southwest chute between Crags 2 and 3 to the 2-3 notch, following Route 1 from the notch.

Crag 4 (12,250)

Class 3. First ascent by David R. Brower, Hervey Voge, and Norman Clyde on June 24, 1934. From the southwest reach the 3-4 notch and follow the much-broken westerly side of the northwest arête to the summit. Descend the same route. A traverse would involve an 800-foot descent on a steep, ledgeless face.

Crag 5 (12,250)

Class 3. First ascent by David R. Brower, Hervey Voge, and Norman Clyde on June 25, 1934. From the northeast climb the floor of the northeast chute between Crags 4 and 5, keeping to the left branch at the extreme top. From the notch contour into the shallow western chute, up which there are several variations in route to the arête above. Follow the arête to within about 25 feet of the summit monolith, contour around the western side, and walk up the south debris to the summit. There are several routes of descent on the southeast arête.

Crag 6 (12,250)

Class 3. First ascent by David R. Brower, Hervey Voge, and Norman Clyde on June 25, 1934. From the northeast follow the arête from Crag 5 to the 5-6 notch, and ascend the west side of the northwest arête.

Crag 7 (12,250)

Class 3. First ascent by David R. Brower, Hervey Voge, and Norman Clyde on June 25, 1934. From the northeast walk up the northwest arête from the 6-7 notch, which has been reached by the traverse of Crags 5 and 6. Descend the southwest chute, roping down in the lower portion.

Crag 8 (12,250)

Class 2. First ascent by David R. Brower, Hervey Voge, and Norman Clyde on June 25, 1934. From the southwest climb the southwest chute between Crags 7 and 8, and follow the northwest slope to the summit.

Crag 9 (11,950)

First ascent by Glen Dawson and Jules Eichorn on August 1, 1933.

Route 1. From the northeast or the southwest. Class 4. Climb to the notch between Crags 8 and 9 by either the northeast or southwest chutes. From the notch climb up and slightly to the west onto the arête, which is followed just below and to the north of its crest to the summit.

Route 2. Traverse. Class 4. A traverse involves a little climbing and two rope-downs into the 9-10 notch, from which one may descend by traversing Crag 10.

Crag 10 (11,950)

First ascent by David R. Brower, Hervey Voge, and Norman Clyde on June 23, 1934.

Route 1. From the northwest. Class 4. Traverse Crag 9 to the 9-10 notch and follow the west side of the northwest arête to the summit.

Route 2. From the southeast. Class 2. Climb the northeast chute between Crags so and 11 to the 10-11 notch. Traverse to the northwest, over a subsidiary crag and along the arête to the summit.

Crag 11 (11,950)

Class 4. First ascent by David R. Brower, Hervey Voge, and Norman Clyde on June 23, 1934. Climb the northeast chute between Crags to and 11 to the 10-11 notch. From the notch climb up toward the summit over rather exposed pitches on somewhat broken rock.

Mount Woodworth (12,214; 12,219n)

Class 2. First ascent by Professor Bolton Coit Brown on August 1, 1895, who climbed straight up the southwest spur, and above this followed along the base of the jagged spires bounding the southern face. Descent was along the easterly edge of the south face.

Peak 12,317 (12,320+; 3/4 SE of Piute Pass)

Class unreported. First ascent on July 3, 1939, by Jim Harkins, Fred Toby, and Bert Malcolm. Contour from Piute Pass to the north shoulder and then follow this to the summit.

Peak 12,702 (12,707n; 1.5 SE of Piute Pass)

Class 2. First ascent by John Cahill and Neil Ruge on July 9, 1933, from the north fork of Lamarck Creek.

Peak 11,257 (11,215n; 1 SE of Lake Sabrina)

Class 1. First ascent by Chester Versteeg on July 21, 1939. An easy climb from Lake Sabrina southeast and up to the summit monolith, where a shoulder stand is required.

Table Mountain (11,707; 11,696n)

Class 1. First ascent October 24, 1931, by Norman Clyde. The easiest route is along the trail between George and Tyee Lakes until beneath the summit rock pile.

Peak 13,202 (13,198n; 1 SE of Mount Lamarck)

First recorded ascent of this peak was made by Norman Clyde in 1925, but the route and class are not recorded.

Peak 11,827 (11,800+n; 2 S of Lake Sabrina)

Class 2. First ascent by Angus E. Taylor on July 29, 1936. This peak is an easy climb from the west and south except near the summit.

Peak 11,943 (11,936n; 1/2 W of South Lake)

First ascent 1918 by Walter L. Huber.

Peak 12,993 (12,993n; 1.5 N of Mount Thompson)

First ascent by Norman Clyde on November 7, 1931. A class 1 climb along the east arête and a class 2 climb from the southeast face.

Peak 13,100+ (13,120+n; 3/4 E of Mount Haeckel)

The first ascent of this peak was on June 27, 1931, by Norman Clyde.

Peak 13,029 (13,000+n; 1 NE of Mount Thompson)

First ascent by Chester Versteeg on July 24, 1939. He did not climb the summit block.

Peak 13,350 (13,323n; 3/8 NE of Mount Thompson)

Norman Clyde made the first ascent of this peak on September 6, 1931.

Peak 13,000+ (13,300+n; 1/2 N of Mount Powell)

First ascent of this peak was accomplished by Walter L. Huber and James Rennie on August 1, 1925.

Hurd Peak (12,224; 12,219n)

Class 2. First ascent by H. C. Hurd in 1906, route unknown. It is a class 2 climb from Treasure Lakes via either the east or west face.

References

Various authors. Sierra Club Bulletin: 1895, 221-37; 1896, 287-8; 296-337; 1899, 259; 1901, 255; 1905, 233, 235, 237; 1913, 52-3; 1921, 117, 140, 144-6; 1922, 251, 275-89; 1923, 417-20; 1924, 87-90; 1926, 220-2, 250-1, 306-7; 1927, 379-80; 1928, 81; 1929, 87; 1931, 104-5; 1932, 19-20; 1934, 19-23, 93-5, 97; 1936, 102; 1938, 14; 1939, 127-8; 1942, 128.

Photographs: (References are to annual magazine numbers of Sierra Club Bulletin)

Black Giant: 1931; 11. Charybdis: 1924, 12, 20. Darwin: 1905, 232; 1922, 286; 1934, pl. XVII (summit pinnacle); 1952, 28-29. Devil’s Crags: 1904, 2; 1914, 162, 163, 188, 189; 1931, 15; 1934, 20, pl. X. Fiske: 1923, 418, 419; 1934, pl. IV. Haeckel: 1921, 145; 1922, 279; 1923, 418. Hermit: 1931, 7; 1934, pl. II. Hurd Pk.: 1915, 306; 1938, 14. Huxley: 1921, frontis., 117; 1934, pl. IV; 1952, 28-29. Langille: 1934, pl. VI. Powell: 1922, 275; 1926, 248. Scylla: 1924, 12, 17. Spencer: 1921, 144; 1934, pl. IV. Thompson: 1922, 275. Wallace: 1905, 235; 1934, pl. IV.

Next: Palisades • Contents • Previous: LeConte Divide

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/climbers_guide/evolution_black_divide.html