[click to enlarge]

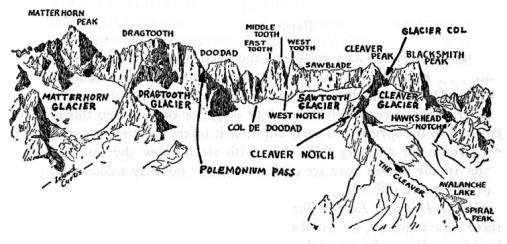

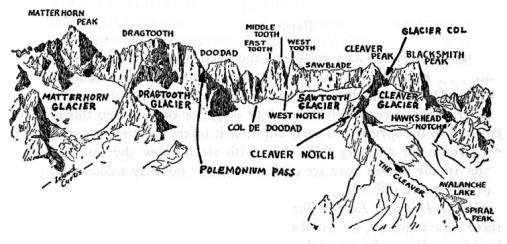

Sketch 3. The Sawtooth Ridge from the northeast.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Climber’s Guide to the High Sierra > The Sawtooth Ridge >

Next: Bond to Tioga—Other Peaks • Contents • Previous: Bond Pass to Tioga Pass

THE SLENDER PINNACLES and narrow arętes of the Sawtooth Ridge form a portion of the northeast boundary of Yosemite National Park. The main peaks are shown on the U.S. Geological Survey map (Bridgeport Quadrangle) and on the map of the Yosemite National Park, but the accompanying Sketch 3 must be consulted for more complete detail and for names not shown on the official maps. Although the peaks are only from 11,400 to 12,281 feet in elevation, nevertheless they constitute one of the most interesting and difficult climbing regions

[click to enlarge] Sketch 3. The Sawtooth Ridge from the northeast. |

The region may be reached from the south by good trail from Tuolumne Meadows to campsites below Whorl Mountain, in Matterhorn Canyon at 9,600 feet, and north of the Finger Peaks, in Slide Canyon, at 10,000 feet elevation. However, the peaks are more accessible from the north, via Bridgeport and Twin Lakes. By a climb from the road of only 3,000 feet in three miles, without trail, a fine campsite can be reached at an altitude of 10,000 feet near a glacial lakelet on the east branch of Blacksmith Creek. Good camping is available on the west branch of the same creek. Campsites are also to be found on the headwaters of Horse Creek at somewhat higher elevations, and these sites are closer to the Three Teeth and the peaks to the southeast.

Although Matterhorn Peak was climbed in 1899, most other points seemed too difficult until modern methods of rock climbing were introduced in the summer of 1931. With the application of a new technique all major points have now been ascended. There are, however, several minor summits yet unclimbed, and many fine new routes still to be made.

Polemonium Pass. Class 3. This is the deep notch between the Doodad and the Dragtooth. The southwest side is class 2, and presents no difficulties. On the northeast a very broad, steep chute descends to the glacier. For 500 vertical feet the slope is 45° or over. When this is snow-covered in the spring and early summer it offers an attractive mountaineer’s route for crossing the ridge, with steep snow the only problem. Later in the season bare ice and a bergschrund may make this northeast side more difficult.

Col de Doodad. East chimney, south to north. Class 4; 200-foot reserve rope required, ice axe useful. This pass was first used July 2, 1933, by Henry Beers, Bestor Robinson, and Richard M. Leonard. It is the most convenient route from Slide Canyon to the northeast face of the central portion of the ridge. The approach from Slide Canyon is up easy scree to the lowest and most prominent gap between the Three Teeth and the Doodad. The 45° couloir on the north is usually snow-filled in the upper half and is bare disintegrating granite in the lower parts. From the col, rappel down the snow coo feet to a ledge. Traverse 10 feet horizontally left (NW) to the head of a dry disintegrating chimney. From there rappel 90 feet to a steel spike driven into a crack in the right (NE) wall at the head of a steep 60-foot drop to the glacier. A third rappel brings one to the head of the glacier.

Col de Doodad. West chimney, north to south. Class 3. From the northeast ascend a moderate 35° gully close against the East Tooth. Follow this gully left (SE) under an overhanging block to the crest of the ridge. Thence, drop to the right (SW) 30 feet over moderately hard climbing to a platform, then to the left (SE) to a chockstone at the head of a short steep chimney. Climb down this chimney to the scree gully on the south side of the Col de Doodad. This route is much easier from north to south than the East Chimney and is somewhat easier from south to north, but should be attempted in the latter direction only by those experienced in route finding as it is poorly defined from the Slide Canyon side.

Glacier Col. Class 2; ice axe advisable. The ascent of this pass between Cleaver Peak and Blacksmith Peak is over moderate scree and benches from Slide Canyon and 40° snow and glacier on the north. It is probably the least difficult pass across the Sawtooth Ridge.

Cleaver Notch. Class 2. First used July 2, 1933, on the first ascent of the Three Teeth. It is the most practical route across the exceedingly sharp aręte of the Cleaver. The notch is crossed at its southern edge, only 30 feet above the glacial benches on either side.

Hawk’s Head Notch. This notch is on the aręte about 100 yards north of Blacksmith Peak just short of the sharp minor pinnacle with the overhanging summit known as the Hawk’s Head. The eastern approach is moderate, but on the west very difficult crack climbing may be required; details are not available.

Twin Peaks (12,314)

Early records are not available. The saddle between the two peaks stay be reached from the north or the south, and both peaks may be readily climbed from this saddle. Class 2 to 3.

Matterhorn Peak (12,281)

Route 1. South face. Class 2. First ascent 1899 by M. R. Dempster, J. S. Hutchinson, Lincoln Hutchinson, Charles A. Noble. This peak, the highest point of the Sawtooth Ridge, offers the most extensive view in the region. There is an easy route from near Burro Pass up the broad scree gully on the center of the southwest face.

Route 2. Northwest face. Class 3. First ascent July 20, 1931, by Walter Brem, Glen Dawson, and Jules Eichorn. Proceed from Matterhorn canyon to the notch between the Dragtooth and the Matterhorn Peak, and climb up a gully, or the face, to the summit.

The Dragtooth (12,150)

Route 1. South face. Class 2. First ascent July 20, 1931, by Walter Brem, Glen Dawson, and Jules Eichorn. Nearly any portion of the south face will be found practicable.

Route 2. North face. Class 4. First ascent July 16, 1941, by J. C. Southard and Hervey Voge. From the Dragtooth Glacier ascend the steep snow slope below the north face to a point about 100 feet to the left (E) of the main chute that comes down the north face. This chute is just east of the massive northwest buttress. Leave the snow by ledges leading up to the left, and follow these ledges to a less prominent chute that lies about 200 feet east of the main chute. Climb this chute for about 200 feet and then cross over to the right to the main chute. Climb up the left (E) side of the main chute to within 100 feet of the summit ridge, and then ascend a 75-foot chimney which leads to the ridge about 50 feet northwest of the summit.

Route 3. Northeast buttress. Class 4. Ascended 1952 by Joe Firey, Norm Goldstein, Chuck Wharton, and John Orrenschall. From the Dragtooth Glacier proceed to the base of the buttress, and ascend it largely on the eastern flank. Higher up stay directly on the crest, which ends in a short chimney below the summit.

The Doodad (11,700)

Class 4. First ascent July 7, 1934, by Kenneth May, Howard Twining. Several routes varying from difficult to very difficult, are possible up the south face to the 25-foot granite cube which forms the summit and which overhangs on all sides. The final climb is up a crack on the southeast corner. On September 7, 1936, Carl Jensen made a traverse by descending the more difficult crack on the northwest corner. There is another route on the southwest corner.

The Three Teeth (11,750)

Route 1. Traverse northwest to southeast. Class 4; rappel rope required. First ascent July 2, 1933, by Henry Beers, Bestor Robinson, and Richard M. Leonard. (See “Three Teeth of Sawtooth Ridge,” SCB, 1934, 31-33.) The route is up a series of ledges in a broad depression on the center of the northeast face of the West Tooth. Several variations are possible at the start. About one-third of the way up, traverse diagonally upward to the right (SW) to less difficult ledges leading upward to the sawblade. Follow the aręte back to the left (SE) to the tunnel beneath the summit block. Climb to the northwest out of the tunnel, and then up the northwest face of the block to the summit of the West Tooth.

From a point at the southeast end of the tunnel rappel 75 feet toward the Middle Tooth to a 3-foot ledge. Climb downward toward Slide Canyon 100 feet along steeply sloping ledges and cracks. Traverse back northeast to the West Notch. Ascend a chimney rising from the notch toward the summit of the Middle Tooth. Follow this chimney about Zoo feet until easier face climbing appears on the left (NE). Traverse this face diagonally right (SE), cross the chimney about 50 feet below the summit, and then by good holds on the face to the right of the chimney climb to the summit of the Middle Tooth.

The route down to the East Notch follows a short chimney near the northeast end of the summit, then steep cracks to the head of the large chimney a short distance below the notch on the Slide Canyon side. Traverse southeast 75 feet along ledges on the Slide Canyon face of the East Tooth to a narrow steep chimney up the face. Climb the chimney to a chockstone, then traverse to the right (SE) a few feet on small holds out of the chimney to a parallel crack. Follow this crack to the summit of the East Tooth.

From the summit follow the Slide Canyon side of the southeast aręte down over steep, exposed and very difficult climbing. About half-way down this aręte a pinnacle about 20 feet high will be encountered. This can be passed by direct attack and a rappel down a steep chimney on the opposite (SE),,side to less difficult climbing leading to the Col de Doodad. A better route is to turn right at the Pinnacle and descend the southwest face over progressively easier climbing to the Slide Canyon base of the Middle Tooth.

Route 2. Traverse southeast to northwest. Class 5. First ascent July 25, 1934, by Glen Dawson and Jack Riegelhuth. From a short distance below the Col de Doodad, on the Slide Canyon side, ascend the short chimney with the overhanging chockstone leading to the aręte and the west chimney of the Col de Doodad. Follow the aręte to the base of the tall pinnacle. Pass this on the left by crawling through a remarkable tunnel on the southwest, to more difficult climbing leading back to the southeast aręte. Thence by Route 1 to the summit of the East Tooth. A more obvious route is from the Slide Canyon base of the Middle Tooth to the tall pinnacle on the southeast aręte of the East Tooth and thence to the summit.

Traverse the Middle Tooth by Route 1, thence to the base of the rappel on the West Tooth. The angle of the next 75 feet is about 80°, highly exposed. The holds are rather unsound. Protected by pitons, the ascent is made up thin cracks and narrow ledges to the tunnel, thence by Route 1 to the summit of the West Tooth. Route i may then be followed to the base on the northeast, or various routes hereinafter described may be used for rappelling the Slide Canyon face.

Route 3. The Middle Tooth from the north. Class 4; ice axe required. First ascent July 2, 1933, by Lewis F. Clark, Richard G. Johnson, Oliver Kehrlein, and Randolph May. From the northeast, ascend the steep snow couloir leading toward the West Notch. One hundred feet above a chockstone leave the snow and traverse diagonally back northeast on a ledge on the left (SE) wall. When snow is low some difficulty may be experienced in getting on the ledge. After traversing the ledge fairly well onto the face, ascend a prominent chimney and ledges upward to the right (SW) to a point on Route 1 in the chimney rising from the West Notch. Follow Route 1 to the summit.

Route 4. The West Tooth from the southwest. Class 5. First ascent July 23, 1941, by David R. Brower, L. Bruce Meyer, and Art Argiewicz. From the scree slope at the base of the West Notch, on the Slide Canyon side, begin climbing up the left (W) shoulder, working diagonally toward a ledge at the top of the lowest and first chimney. From this point a delicate fingertip traverse is necessary to cross the top of the chimney to another scree chute directly above the lower chimney. After ascending the chimney to about 30 feet below its mouth one must work back (SW) and to the left (W) over an easy ledge. After working over this ledge a short distance, ascend the chimney above by swinging around a flake to the left (W) and above the ledge and then using cross pressure in the chimney. At the top of this chimney work to the left (W) and then up the southwest face to the prominent vertical face of the West Tooth. From here the summit is reached as in the last part of Route 2.

Route 5. West Notch from the glacier. Class 4 to 5. In 1949 Oscar Cook, Joe Firey, Larry Taylor, and Jack Hansen ascended the couloir or chimney leading to the West Notch from the northeast. From the notch traverse directly out to the right on a hand ledge ending in a chimney which leads straight up to the end of the tunnel.

Rappel Routes. Class 5 to 6; 200-foot rappel rope required. By the use of many pitons nearly any route is probably possible. It is well, however, to mention certain routes that have actually been used. Slide Canyon can be reached from the northwest aręte of the West Tooth near the junction with the Sawblade by a series of four rappels involving the use of one piton. It is also possible to rappel from the West Tooth toward the Middle Tooth by Route 1 and thence by three more rappels along the southeast buttress to Slide Canyon. The last rappel, from a piton on a ledge, is 105 feet, most of it overhanging. From the West Notch it is practicable to rappel the north chimney to the glacier, though the last rappel is about 125 feet. A successful rappel route from the Middle Tooth to Slide Canyon by the great southeast chimney from the East Notch has been followed. Another route down from the Middle Tooth, to the north base, proceeds from the lower end of the chimney on the northwest face, the upper part of which forms a portion of Route 3. About half of the last rappel is overhanging. A severe route, not recommended, goes down the north face of the East Tooth from the East Notch; it involves the use of pitons, and slings to sit in as one of the intermediate stances.

The Sawblade (11,600)

Traverse south to north. Class 4; rappel rope useful. First ascent July 25, 1934, by David R. Brower, Hervey Voge. From Slide Canyon the route proceeds up steep climbing to the notch just west of the tall pinnacle on the northwest aręte of the West Tooth. An attempt to faverse this portion of the Sawblade to the West Tooth was blocked by the pinnacle which could not be turned. Descent was made to the northeast.

Cleaver Peak (11,850)

Route 1. Southwest face. Class 3. First ascent July 3, 1933, by Henry Beers and Oliver Kehrlein. From Glacier Col climb on to the southwest face and traverse diagonally upward to the left (N) to a broad depression on the northwest face. Follow this to the summit.

Route 2. Northeast face. Class 3. First ascent July 27, 1934, by Glen Dawson and Jack Riegelhuth. Go up a series of ledges and blocks on the northeast face to the aręte of The Cleaver 50 feet north of the summit. Traverse the aręte to the summit.

Route 3. South face. Class 5. Ascended August 6, 1950, by M. L. Wade and F. Chrisholm. Ascend a chute (easy class 4) facing Burro Pass until within about 150 feet of the notch separating Cleaver Peak from the Sawblade. Here a large block leans against Cleaver Peak. (By climbing under this block one reaches the notch southeast of Cleaver Peak.) Turn left at the lower side of the block and ascend the south side of Cleaver Peak. Several interesting fifth class pitches.

Blacksmith Peak (11,850)

Route 1. Southwest face. Class 3. First ascent July 3, 1933, by Bestor Robinson and Richard M. Leonard. Go up a prominent gully on the southwest face to its head among the four summit pinnacles. The highest is on the northwest end. The register is on the flat-topped pinnacle third from the highest.

Route 2. The north gully. Class 5; pitons required. First ascent September 8, 1936, by Bestor Robinson and Carl Jensen. From the base of the north aręte ascend a steeply sloping ledge on the Cleaver Glacier side diagonally upward toward the south. About 200 feet above the talus the ledge ends against a vertical face. Traverse to the right (W) and protected by several pitons climb about 20 feet of face on small holds to the large north gully. Ascend this gully to its head among the summit pinnacles. On the first ascent (1933) the peak was traversed from south to north by rappelling from the lower end of the north gully.

Eocene Peak (11,555; 1 NW of Blacksmith Peak)

Class 3. First ascent July 16, 1932, by Herbert B. Blanks and Richard M. Leonard. A ropeless ascent may be made of the southwest slopes of this fragment of the ancient Eocene landscape. The final pinnacle rising 50 feet above the plateau may require ropes for inexperienced climbers.

Other peaks and ridges

There are many minor pinnacles and sharp ridges in the Sawtooth area that offer enjoyable climbing. These are not listed in detail. Many have been climbed, while others have yet to be visited. Worthy of mention are The Cleaver, including Spiral peak at the lower end, the ridge running north of Blacksmith Peak, the ridge north of Eocene Peak, and the northeast side of the ridge between Twin Peaks and Matterhorn Peak.

References

Text: SCB, 1934, 31, 98; 1935, 46, 105; 1942, 126.

Photographs: SCB, 1900, pl. 23; 1934, 46-47 (Dragtooth, Three Teeth from the north); 1935, 110-111 (Blacksmith Peak; Three Teeth from the south).

Next: Bond to Tioga—Other Peaks • Contents • Previous: Bond Pass to Tioga Pass

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/climbers_guide/sawtooth_ridge.html