[click to enlarge]

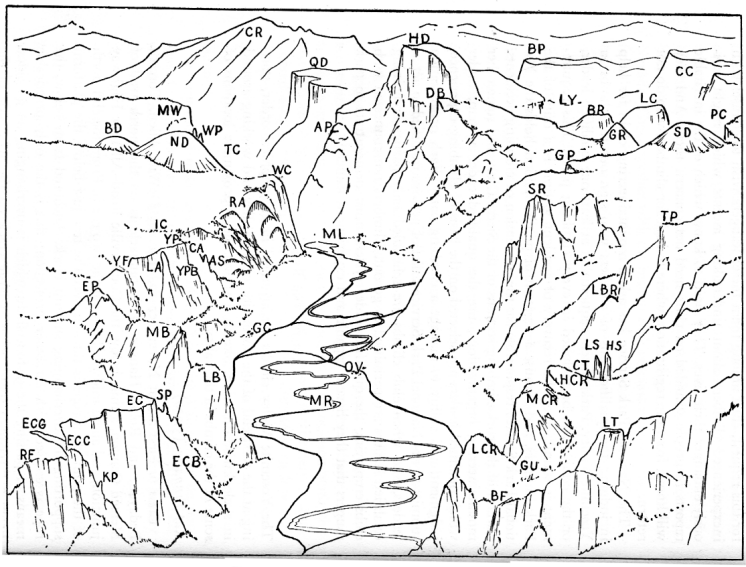

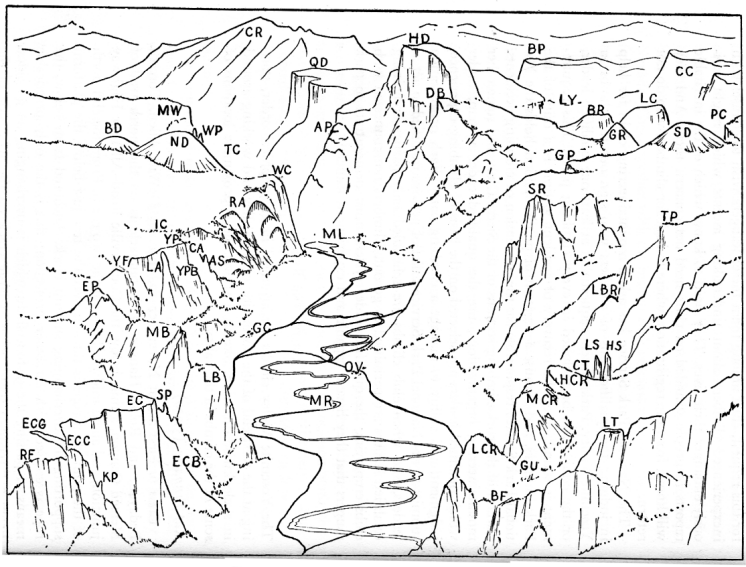

[Sketch 4. Yosemite Valley Climbs.]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Climber’s Guide to the High Sierra > Yosemite Valley >

Next: Cathedral Range • Contents • Previous: Tioga Pass to Mammoth Pass

YOSEMITE VALLEY offers one of the finest localities in America for a sport that has made the Kaisergebirge and the Dolomites internationally famous—concentrated rock climbing. Long enjoyed throughout the world as complete in and of itself, this sport does not require attainment of high summits, but tends to emphasize route finding, whether on summits, walls, or arêtes. For that reason Yosemite has been a mecca for pure rock climbing for many years, more perhaps than any other region in the country.

Even in those prehistoric days before the discovery of the incomparable valley, there were legendary rock-climbing exploits. Such was the first descent to the base of the Lost Arrow. The Indian maiden, Tee-hee-neh, rappelled on lodgepole saplings joined with deer thongs to recover the lifeless body of her lover, Kos-soo-kah. By means of thongs and the strong arms of other members of the tribe, they were brought back to the rim of the valley, where Tee-hee-neh perished in grief. This legend is reported in many different sources; Hutchings, in 1886, stated the height of the rappel to be 203 feet, a truly remarkable rock-climbing achievement.

It was not until 1833 that the white man is known to have seen Yosemite Valley. From reports published long before the later and widely publicized discovery of the valley, we learn that Joseph Reddeford Walker and party came from the vicinity of Bridgeport, perhaps over Virginia Pass and along the divide between the Tuolumne and the Merced rivers, to the valley rim. There they marveled at waterfalls over “lofty precipices . . . more than a mile high.” The first rock-climbing attempt by white men was soon stopped by difficulty, for “on making several attempts we found it utterly impossible for a man to descend.”

In 1851, however, Yosemite Valley was really made known to the world, when the Mariposa Battalion, organized by harassed settlers of the foothills, trailed Indians to their stronghold in Ahwahnee—“deep grassy valley.”

[Editor’s note: Ahwahnee does not mean “deep, grassy valley.” Ahwahnee means “mouth” because the valley walls resemble a gaping bear’s mouth. For details see the article “Origin of the Word Yosemite.” —dea]

Yosemite soon became a source of attraction for tourists from all over the world. One of the earliest to arrive was James M. Hutchings, who first came to the valley in 1855. Throughout the early history of the valley he was interested in attempting to climb every point around the valley.

John Muir first came to the Sierra in 1868. Through him more than any other man has the beauty of the region been made known to the entire world. His climbs in Yosemite Valley and the High Sierra, many of them the earliest of which we have knowledge, place him among the pioneers of California mountaineering. His Sunnyside Bench, east of the lip of Lower Yosemite Fall, is still one of the untrammeled beauty spots of the valley. His early exploration of the Tenaya Canyon led to route finding in the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne. He made the first ascents of Cathedral Peak and Mount Ritter, and was first to traverse under the Lost Arrow along Fern Ledge, beneath the crashing power of the Upper Yosemite Fall.

In early October of 1864 Clarence King, assisted by Richard Cotter, fresh from a victory over Mount Tyndall, made the first serious topographical and geological reconnaissance of the Yosemite Valley. On this survey they climbed practically every summit on a circuit of the rim of the valley. This circuit included only the easier points, such as El Capitan, Eagle Peak, Yosemite Point, North Dome, Basket Dome, Mount Watkins, Sentinel Dome and the Cathedral Rocks. Any summits which were much beyond this standard of difficulty seemed to them completely beyond the range of human ability. In 1865 the California Geological Survey wrote concerning Mount Starr King and Mount Broderick, “Their summits are absolutely inaccessible”; and of Half Dome, “it is a crest of granite rising to the height of 4,737 feet above the valley, perfectly inaccessible, being probably the only one of all the prominent points about the Yosemite, which never has been, and never will be trodden by human foot.”

Spurred by this challenge James M. Hutchings and two others made the first recorded attempt on Half Dome in 1869, but were stopped at a saddle east of the Dome. After at least two intervening attempts the Scotch carpenter and trail builder, George G. Anderson, finally engineered his way to the top on October 12, 1875.

Inspired by the success on Half Dome, adventurous climbers turned their attention to Mount Starr King, the “extremely steep, bare, inaccessible cone of granite” referred to by Whitney in the Yosemite Guide Book. George B. Bayley and E. S. Schuyler made the ascent in August, 1876, somewhat to the dismay of Anderson, Hutchings, and J. B. Lembert, who, using a different route, a year later found the summit monuments built by the first party. Bayley was one of the most remarkable climbers of the time. In 1876 Muir recorded that “Mounts Shasta, Whitney, Lyell, Dana, and the Obelisk (Mount Clark) already have felt his foot; and years ago he made desperate efforts to ascend the South Dome (Half Dome), eager for the first honors.” Later he was distinguished by an early ascent of Cathedral Peak, and an ascent of Mount Rainier during which he was seriously injured by a fall into a crevasse, recovering only to be killed in a city elevator.

After the great ascents of the “inaccessible” summits of Yosemite, there was a period of quiet in the climbing history, for everything seemed to have been done. Hutchings had claimed the ascent of all Yosemite points, except Grizzly Peak and the Cathedral Spires, and a climber of another generation came forward in 1885 to make the ascent of Grizzly Peak. He was Charles A. Bailey, who later became an enthusiastic member of the Sierra Club, locating, climbing, and naming Sierra Point for the club.

Since it now appeared that all major summits in the Yosemite region had been climbed, there was a long gap in the climbing history, broken only by the exploratory routes of a few outstanding climbers of the period. Those whose climbs are best known are S. L. Foster, Joseph N. LeConte, Charles and Enid Michael, William Kat, and Ralph S. Griswold. Foster was best known for his canyoneering in the Merced and Tenaya canyons beginning in 1909. LeConte has been remembered through the description of his ascent of the gully on Grizzly Peak, which permits a route to the Diving Board on Half Dome. He also wrote of several other interesting “scrambles about Yosemite” of nearly three decades ago. It has been said of the Michaels that they climbed everything that did not require pitons. The same description might apply to Kat and Griswold. All have been so modest that it is possible we may never know the true history of the interesting routes which they have pioneered. For, wherever a young rock climber attempts a “new route,” he is quite likely to find a cairn or other indication that someone has been there many years before him.

Again it seemed that nothing more could be done. However, in the early thirties, a new phase of rock climbing was growing, based on development of modern technique in Europe. In the summer of 1931, Robert L. M. Underhill, the leading American exponent of the use and management of the rope in rock work, interested Californians in this phase of climbing. It has been mentioned that some very remarkable climbing was done without the knowledge of this safety technique; but the early climbers who have discussed the matter agree that their climbing frequently involved unjustifiable hazard. Moreover, it was clear to all of them that they could not attempt routes of very high angle and small holds. Thus the introduction of a new type of climbing, combined with the protection of pitoncraft, again opened a new field.

It was not until September 2, 1933, that the first rock climbing section of the Sierra Club felt competent to make organized attempts upon the spectacular unclimbed faces and spires of Yosemite. Although as long ago as 1886 Hutchings, in reporting the relatively easy ascent of Grizzly Peak, claimed that the last “unclimbed summit” of Yosemite had been ascended, nevertheless the Cathedral Spires, the Church Tower, the Arrowhead, Split Pinnacle, Pulpit Rock, Watkins Pinnacles, and the Lost Arrow still stood forth without even an attempt ever having been recorded against them. In addition to these summits there was a field, practically unexplored, of route finding on faces, arêtes, gullies, and chimneys. Among these may be mentioned Washington Column, Royal Arches, Panorama Cliff, Glacier Point, Yosemite Point Couloir, Cathedral Chimney, and the arête of the Lower Brother. Ropes, pitons, and trained experience in their use were the keys to these ascents, which were later to become so popular. Climbers, profiting by the achievements of their predecessors, added still more ascents to the growing list of Yosemite routes.

But there was a further challenge. The higher cliffs and arêtes, hitherto neglected, beckoned to the new generations of climbers. These long and severe climbs were not easily judged, but it was obvious that they would demand the utmost in skill and aggressiveness. And so, during the middle forties, as in the Dolomites a decade previously,* a tradition of direct-aid climbing began in which many pitons were used, together with expansion bolts when no suitable cracks were to be found. With this new tradition came the direct ascent of the Lost Arrow in 1947, a success born of dogged determination and great physical endurance, and requiring five consecutive days on the rocks. Still other difficult ascents followed, such as the four-day climb of the north wall of Sentinel Rock, and the three-day climb of the El Capitan Buttress. These severe climbs stand in a class of their own, and the traffic on them is likely to remain light. There are still many routes of apparent moderate difficulty that have not been tried. Also, the climbs first done twenty years ago are popular today and will doubtless remain so in the future.

* Worthy of mention is the first direct ascent of the north face of the Cima Grande (Grosse Zinne), which was accomplished in August, 1933, by three Italian guides using 200 meters of rope, 150 meters of slings, 90 pitons, and 40 carabiners.

Yosemite Valley is now just a few hours from San Francisco and Los Angeles. Campsites are excellently provided for by the National Park Service and need no further details. Accommodations of all types are provided by the concessionaire.

The geology of Yosemite has been under consideration, ever since its discovery, by eminent scientists throughout the world. Of the early conflicting theories, those of John Muir have best stood the test of time and study. These were amplified in detailed studies by François E. Matthes (see References and Maps). Yosemite Valley seems to have had a greater variety of granitic intrusions than most of the Sierra Nevada. This, together with the prominence of master joints, has amplified the effect of erosion. Upon long-continued and alternate sculpture by running water and glacial action, the valley was deepened to essentially its present form. This geomorphological history has produced smooth faces of high angle with holds widely spaced but exceptionally firm. While loose hand or footholds must be expected occasionally, rock as sound for climbing is seldom found. The scarcity of talus piles under the high cliffs is clear evidence of this. On the other hand the infrequency of large holds tends to emphasize precise balance climbing, frequently requiring long leads on minute holds. For this reason plenty of rope should be available; at least 120 feet between climbers, plus 200 feet of rappel rope with ample material for slings. As will be indicated hereafter, pitons are definitely advisable on most climbs, and are essential on many. Most climbers will prefer, wherever possible, to avoid using pitons as direct aid. No party, however, should hesitate to use pitons for safety as frequently as desired even though not specifically recommended by this Guide. The best footgear is rubber. There seems to be no necessity for nails, at least in summer. In common with the rest of The Range of Light, the weather in summer need rarely be considered as a factor in climbing. In general, the altitude is so low and camp so close that no protection against weather need be arranged. Nevertheless, since friction holds play such an important part in climbing on these smooth walls, retreat in case of rain must be adequately planned.

A very useful topographic map of the Yosemite Valley may be purchased at the Government Center or at certain stores in large cities. This is the Yosemite Valley sheet, published by the U.S. Geological Survey in 1938, with a scale of 1:24,000.

The Park Officers request that all parties register with the National Park Service at the Office of the Chief Ranger at Park Headquarters in Yosemite Valley before attempting any climbs, and that they check in at the same place after completing a climb. There are many reasons for this request, chief among them these: Rangers wish to counsel with inexperienced climbers about undertaking ascents which might seriously endanger their lives. They need to know which of the inevitable reports of people stranded on cliffs need not concern them. And they will know, from the registration, where to look for climbers who do not return.

The National Park Service has asked mountaineering clubs for help in judging the qualifications of climbers who sign out for climbs in Yosemite Valley. Park officers request that at least one qualified leader, or the equivalent, be included in every climbing party. This requirement is sound, since the recovery of accident victims is a duty of the Park Rangers, and because a segment of public opinion holds the National Park Service responsible for the prevention of climbing accidents. Several of the rock-climbing sections of the Sierra Club, and some other mountaineering organizations, use the qualified-leader system, under which qualified leaders are selected on the basis of climbing experience, judgment, and ability to manage a climbing party. Each organization submits to the National Park Service a list of persons qualified to act as leaders, and when club climbs are scheduled only parties containing qualified leaders are permitted to go out. Climbers not connected with clubs employing the qualified-leader system must demonstrate to park rangers that they have a capable and experienced leader.

The Yosemite Valley climbs are arranged in geographical order, starting at the west end of the north side of the valley and working around in a clockwise direction. Sketch 4 shows the approximate locations of some of the climbs in the valley.

Kat Pinnacle (3,950)

Class 6. First ascent November to, 1940, by DeWitt Allen, Torcom Bedayan, and Robin Hansen. This pinnacle is on the north wall of Merced Canyon, a mile below the Coulterville Road-All-Year Highway junction, and about midway between the two roads. From the cliff north of the pinnacle a rope is thrown over the tree just below the platform supporting the overhanging summit block. Anchored from below, the rope is crossed with carabiner protection; this is the only practicable means of passing the 90-foot shaft, which is overhanging on all sides. From a three-man stand below a large crack on the west side of the

[click to enlarge] [Sketch 4. Yosemite Valley Climbs.] |

Key to Sketch 4.

(Listed in clockwise order around the valley)

| RF | Ribbon Fall | RA | Royal Arches | PC | Panorama Cliff |

| KP | K.P. Pinnacle | WC | Washington Column | GR | Grizzly Peak |

| ECG | El Capitan Gully | ML | Mirror Lake | GP | Glacier Point |

| ECC | El Capitan Chimney | TC | Tenaya Canyon | SD | Sentinel Dome |

| EC | El Capitan | ND | North Dome | SR | Sentinel Rock |

| ECB | El Capitan Buttress | BD | Basket Dome | TP | Taft Point |

| SP | Split Pinnacle | WP | Watkins Pinnacles | LBR | Lost Brother |

| LB | Lower Brother | MW | Mount Watkins | LS | Lower Cathedral Spire |

| MB | Middle Brother | CR | Clouds Rest | HS | Higher Cathedral Spire |

| EP | Eagle Peak | QD | Quarter Domes | CT | Church Tower |

| LA | Lost Arrow | AP | Ahwiyah Point | HCR | Higher Cathedral Rock |

| YF | Yosemite Falls | HD | Half Dome | MCR | Middle Cathedral Rock |

| YP | Yosemite Point | DB | Diving Board | LCR | Lower Cathedral Rock |

| YPB | Yosemite Point Buttress | BP | Bunnell Point | GU | Gunsight |

| IC | Indian Canyon | LY | Little Yosemite | BF | Bridalveil Fall |

| CA | Castle Cliffs | BR | Mount Broderick | LT | Leaning Tower |

| AS | Arrowhead Spire | LC | Liberty Cap | MR | Merced Riyer |

| GC | Government Center | CC | Cascade Cliffs | OV | Old Village |

An alternate route (Dick Irvin and Dave Hammack) traverses left (E) from the Tyrolean tree along the north side, and then back (W) on a higher ledge. From the northwest corner of the upper ledge pitons are placed for direct aid under and across an overhang. Then a class 5 gully leads to the top.

El Capitan Gully (7,500) Class 3. First recorded ascent June 5, 1905, by J. C. Staats, who continued the climb to the rim to get help after Charles A. Bailey had fallen 400 feet to his death. This, the western of the two gullies between El Capitan and Ribbon Fall, does not involve any real climbing problems until the steep upper 500 feet.

K-P Pinnacle (6,200)

Class 6. First ascent May 30, 1941, by Ted Knoll and Jack Pionteki. This is the second highest pinnacle west of El Capitan between El Capitan Gully and Chimney. The route involves a two-hour bushwack and some class 4 climbing to reach the base of an open chimney, which is surmounted by direct aid. Cross an exposed 4-foot cleft and climb to the 2- by 4-foot summit.

El Capitan (6,750)

West chimney. Class 6. First ascent October 9, 10, 1937, by Ethel Mae Hill, Gordon Patten, and Owen Williams. From the toe of El Capitan follow up along the base of the cliffs (W) to the chimney clearly shown on the map. Chockstones are responsible for seven overhangs which present the principal difficulty. From the notch (6,600) a rappel brings one to the class 4 climbing of the main gully leading to the summit plateau. The initial climb took two days and 18 pitons; a third of the pitons were used for direct aid.

Tree traverse. Class 6. First ascent March 1952 by William Dunmire, Will Siri, Allen Steck, and Robert Swift. From the valley floor this extraordinary pine appears to grow out of the granite wall one-quarter mile east of the main El Capitan abutment and 350 feet above the talus. The overhanging route begins below and to the east of the tree via a ladder of expansion bolts and pitons which have been left by previous parties. After the first 110-foot pitch (average angle 110°), class 4 and 5 pitches lead west to the tree. With an early start the climb can be made in one day. (SCB, 1952, 93-94.)

East buttress. Class 6. First ascent June 1, 1953, in three days by Will Siri, Bill Long, Bill Unsoeld, and Allen Steck. The buttress forms the eastern edge of the unbroken southern wall of El Capitan. The approach is the same as for the Tree Traverse, only upon reaching the foot of the wall traverse right (E) to the foot of the arête and ascend a class 6 chimney 110 feet to a scrub oak. Climb up (class 4) to the foot of a 60-foot wall which can be climbed on its steep left (W) side by use of sound holds and one piton for protection. Traverse slightly left and upward over easy ground to base of open chimney leading to the nose directly on the arête. Ascend directly to nose (class 4-5). From this platform two class 6 leads, on perhaps the steepest portion of the buttress, and a short class 5 pitch lead to some small ledges (site of second bivouac). The wall to the right of these ledges was ascended (class 6) in two leads to a large ledge. Traverse right a few feet and climb a short 5-foot chimney to the final 70-foot lead up a steep broken wall (class 5-6). Several attempts were made here, the chimney farthest to the right (E) offering the best route. The two final days of the ascent were during rainy weather; other ascents could be made in two days, or possibly one day.

Split Pinnacle (5,100)

Class 6. First ascent May 28, 1938, by Raffi Bedayan, Muir Dawson, Richard M. Leonard, and Jack Riegelhuth. Follow the west fork of Eagle Creek to the 5,000-foot contour and circle back to the southwest corner of the West Pinnacle. An easy upward traverse on the valley side of the West Pinnacle, past its class 3 summit, brings one to an ample ledge beneath the 25-foot, 117° summit pitch. A shoulder-stand and three well-placed pitons with slings enable the leader to grasp excellent hidden holds on the edge of a ledge on the extreme left. Use minute transient footholds and pull up onto the ledge, from which the summit is easily reached. This pinnacle is one of the most popular short climbs in the valley.

Lower Brother (5,900)

Michael’s Ledge. Class 4. First recorded ascent in the twenties or earlier by Charles W. Michael. From the south base a broad tree and brush-covered ledge spirals high up the east face, and may be easily followed to a point swept by recent rock avalanches from the Middle Brother. From here the ascent over scree-covered ledges and slabs to the arête which forms the summit is exposed enough to require consecutive roped climbing.

West face—north corner. Class 5. First ascent October 21, 1934, by H. B. Blanks, Boynton Kaiser, and Elliot Sawyer. Although the average angle is not high, the rounded character of the holds, polished by winter avalanches, and the ten-foot overhanging steps make this a good climb. The route follows closely the angle formed by the intersection of the Lower and Middle Brothers, and the problem is mainly one of friction. Bypass difficult sections of the corner on the right (S).

West face—middle. Class 5. First ascent April 22, 1952, by Donald Goodrich and Gary Lundberg. Follow the first ledge leading from the angle between the Middle and Lower Brothers to the right past a tree to its far end; here a delicate pitch leads around and up a corner onto a large slanting slab. Continue south on ledges for about 100 feet and work up toward the vertical wall that divides the face. Surmount this wall and climb up several pitches more to the summit.

Southwest arête. Class 5. First ascent July 15, 1937, by David R. Brower and Morgan Harris. Ascend Eagle Creek until 300 feet below the prominent black chimney in an angle of the west face. Traverse (SE) on a broad tree-covered ledge, where a moderately difficult crack leads up the west face about 30 feet. From here a delicate friction traverse leads to the left (N) where a shelf, a short chimney, and easy pitches continue straight up over smooth mossy cracks in unsound rock; then traverse right (E) across a smooth gully to a broad ledge. Ascent of a 50-foot friction pitch, slanting upward (E) brings one to the base of an open, almost holdless, chimney at an angle of about 70°. From the top of the chimney a short traverse (W) leads to the broken south edge of the upper west face. From here easy climbing leads to the summit.

Another class 5 route on the south arête starts from about 300 feet up Michael’s Ledge. Here a much smaller ledge leading diagonally upward and to the left (W) should be followed out on to the south face. An ascent directly upward from the tree where the upper end of the ledge terminates brings the climber to an alcove. From here a narrow 50° chimney opening higher up leads eastward. At the end of this chimney another open chimney leads directly upward. Several pitches in this chimney bring the climber to the upper granite slabs where climbing may be done continuously to the summit. There are several variations of this route.

The several routes on the Lower Brother are among the most popular one-day ascents in the valley.

Middle Brother (6,850)

West face. Class 4. First ascent either by Charles W. Michael in the twenties or by Ralph S. Griswold and William Kat in the early thirties. Follow Eagle Creek to about 5,850, then climb out to the right and up steep slabs to the arête. The lower point overlooking the Lower Brother should probably be considered the summit of this sloping ridge.

From Michael’s Ledge. Class 4. First ascent June 2, 1951, by Ronald Hahn, David Hammack, Anton Nelson, and John Salathé. Follow Michael’s Ledge (see Lower Brother for description) clear on around (NE) past the Lower Brother and through dense brush to a point where the angle of the headwall is quite low. There are many tree-covered ledges that lead toward the summit of the Middle Brother. The climb is minimum class 4.

Southwest arête. Class 5. First ascent May 30, 1941, by David R. Brower, Morgan Harris. See Lower Brother climbs for the routes to the notch between Middle and Lower Brother. From just west of the notch traverse diagonally upward and to the right on class 4 rocks for about 50 feet, then climb straight up for another pitch. Since the face rises sharply in holdless cracks, a traverse horizontally to the left (W) a few feet around a little nose is advisable; then ascend about 15 feet over smooth holds to a small ledge. On the first ascent a shoulder-stand enabled the climbets to overcome the bulging overhang above. Beyond lies a little alcove under a big block overhang which looks impossible from below. However, just under the overhang, holds permit a traverse to the right (E) around the block to the ridge. Exposed scrambling leads to the indefinite summit of the Middle Brother.

Southwest arête—variation. Class 6. First ascent May 1950, by Nick Clinch, David Harrah, Sherman Lehman, and John Mowat. From the crest of Lower Brother traverse left (W) for two rope lengths. Climb up a short overhanging chimney and a steep slab to a pine seen from the Lower Brother. Continue up slabs, past a small platform, to an alcove. Work right to a flat ledge, around a corner, and up an easy crack to a broad, sloping ledge. Walk down and to the left on the ledge to where a smooth overhang intervenes. So far, all parties have used a direct-aid piton or two to cross the overhang. On the far side work up and around the corner of the south face to the west face. Climb up the arête for several hundred feet. then proceed tin a scree gully and cross onto the south face. A thin horizontal ledge leads to where the west face may be regained. Work across flat ledges in the face to an easy gully leading to the summit.

At least one ascent of the Middle Brother has been made via the southwest arêtes of the Lower and Middle Brothers. This combination of routes requires efficient teamwork if it is to be accomplished in a day.

Eagle Peak (7,773)

From Camp 4. Class 6. First ascent early June, 1952, by Ron Hayes and Jon Lindbergh. From the top of the talus directly above Camp 4, walk (W) toward the large clump of trees on the prominent ledge. The climb, a long chimney, begins just to the east of the trees. It presents the only ascending route in the area which appears climbable without extreme difficulties. Climb up through a tree and into the chimney. The route continues up a series of increasingly difficult secondary chimneys to a final overhanging mossy chimney which requires many direct-aid pitons. Above, one more pitch and a long bushwhack lead to Eagle Peak and the trail.

Rixon’s Pinnacle (4,600)

Class 6. First ascent August. 1948 by Charles and Ellen Wilts. This is the 400-foot remnant of an exfoliation slab against the vertical south face of the Middle Brother. The first pitch is 150-feet long (two ropes were used on the first ascent) and leads to a prominent tree. Above, a short, difficult Mummery crack is climbed to a small ledge, and an open chimney continues farther. An easier class 6 pitch ends at the second tree, from which point several varied pitches lead to the summit. The original ascent took two days and required about 60 pitons (SCB, 1949, 148-149).

Lower Yosemite Fall (4,420)

West side. Class 4. First ascent September 13, 1942, by Alan M. Hedden and L. Bruce Meyer. From the bridle-path bridge follow the creek and talus up the left (W) side of the fall as far as possible. At the head of the talus a crack leads over flakelike rocks up to a ledge 40 feet above the talus. At this point ascend a small crack leading to the right to some bushes, then continue upward to a large fir tree. Proceed left around an overhanging rock and then vertically to a ledge. Climb to the right and continue right on another ledge a few feet lower. The route then leads upward to a tree clump, right around a nose, and up a grass-covered ledge leading to the top of the fall. The rock on this climb is generally insecure, so care should be taken not to dislodge rocks onto tourists who might climb to the talus below.

Gorge traverse (between upper and lower falls). Class 5. Low water only. First ascent by Dave Hammack and George Larimore, 1950. From the top of Lower Yosemite Fall an easy walk on the west side of the creek for several hundred feet follows. The first major cascade is passed to the left (W) until progress is blocked; then traverse right to the brink of this fall. The route then follows a steep granite slope to the left of the creek to a point about 75 feet above it where progress is blocked by a 15-foot overhang, which may be climbed beside a tree on the somewhat broken face. From here it is easy going to the base of the Upper Fall.

Sunnyside Bench (4,420)

Waterfall route. Class 4. First ascent July 22, 1935, by David R. Brower and William W. Van Voorhis. On the right (E) side of the stream a short distance above the Lower Yosemite Fall bridge easy cracks and ledges lead to the right (E) to a small platform about 40 feet above the stream. From here the route ascends vertically through a shallow chimney and up a difficult friction slab to the tree-covered ledge.

South face route. Class 4. First ascent unknown. About 50 yards east of the Lower Yosemite Fall horse trail bridge, just above the Lost Arrow Loop Trail, a deep chimney leads upward and to the east. The route follows this chimney to a large ledge leading to the right (S) of the chimney. From the’ ledge work out onto the south face and up a 70° crack on the otherwise smooth granite. The crack ends at Sunnyside Bench. The top of Lower Yosemite Fall may be reached by traversing on the ledge around the corner to the left (W). The south face may be superior to the waterfall route during high water.

Although Sunnyside Bench may be climbed by a brushy class 3 route starting from behind Government Center and traversing west (first ascent unknown), the two more direct routes are preferred by climbers and are among the most popular short day ascents in the valley. In late summer the basin above the fall provides a remarkable swimming pool.

Lost Arrow (6,875)

First Error (6,050). Class 6. First ascent May 29, 1937, by David R. Brower and Richard M. Leonard. Since the Lost Arrow, just west of the benchmark at Yosemite Point was facetiously named the “Last Error,” its two ledges and its notch are appropriately called First, Second, and Third errors, respectively, The route to the first ledge leads between a 70° buttress and the 85° face on small holds, highly polished and rounded by water and avalanches. Ascent in the main couloir to a point level with the First Error can be made without direct aid, and a rope traverse to the ledge is possible.

Second Error (6,450). Class 6. First ascent by Anton Nelson and John Salathé, July 4, 1947. A 400-foot, 80° chimney leads from the First Error to this ledge. Many direct-aid pitons are necessary. Time from base is about two days.

Third Error (6,750). Class 6. Reached by John Salathé in August 1946 by a descent from the rim of the valley (SCB, 1947, 2, 3).

Last Error (6,875). Class 6. First ascent September 2, 1946, by Jack Arnold and Anton Nelson, who prusiked up a rope thrown over the summit, and Fritz Lippmann, who came via the Tyrolean traverse which was set up (SCB, 1947, 1-10). First direct ascent from the base, by Anton Nelson and John Salathé, September 3, 1947. The route follows the long chimney via the first and second errors. The ascent was accomplished in five days and required much preparation (SCB, 1948, 103-108).

Yosemite Point Buttress (6,935)

Class 6. First ascent July 1952 by Allen Steck and Robert Swift. The granite buttress forming the southeast wall of Yosemite Point can be divided into two’ parts: the pedestal and the steep face immediately above it. Climb the Yosemite Point Couloir until in line with the broken ledges and chimneys which form the right-hand side and, partly, the face of the pedestal; then aim for the large pine tree visible several hundred feet above. From the tree work upward via class 6 cracks and chimneys to the top of the pedestal, which affords an ample bivouac spot if the climb cannot be completed in one day. Above, an obvious class 6 route continues upward and to the left, then right to a sandy ledge. Several more pitches of varying difficulty lead finally to the summit. Several one-day ascents of the pedestal have been made, but the only complete ascent of the buttress thus far required two days. (SCB, 1952, 91-93.)

Yosemite Point Couloir (7,250)

Class 6. First ascent June 8, 1938, by Torcom Bedayan, David Brower, and Morgan Harris. This is the prominent gully between Yosemite Point and Castle Cliffs. Its full length may be ascended from the valley floor, at the incinerator behind Government Center, or the lower half may be by-passed with the Arrowhead approach route. Difficulties begin shortly above the halfway mark with a 30-foot, 55° slab of polished granite which may be ascended directly or may be passed on a more exposed route to the right. The next problem, a large chockstone, is overcome by starting some 50 feet below on the east wall and climbing to a narrow, scree-covered ledge, from whose upper end it is possible either to rope-traverse to the top of the chockstone or climb upward. Farther up the couloir a second chockstone may be climbed directly, and a third may be passed by a four-sided chimney behind it. Here the couloir floor rapidly steepens and narrows. From the top of the narrow chimney ascend the 45° polished granite to an overhang above, which may be climbed class 5. From this point the couloir opens out, and it is but a scramble to the valley rim. The couloir is a long day climb. (SCB, 1939, 63-68.)

Castle Cliffs (6,750)

Class 5. First ascent May 29, 1940, by David R. Brower and Morgan Harris. Follow the usual route toward the Arrowhead (which see). From the main gully below and west of the Arrowhead traverse gradually upward (W) through brush and class 2 scrambling to the last arête before Yosemite Point Couloir. The route leads up this arête some 300 feet, ending after a long bushwhack near the head of the Yosemite Point Couloir. Time for the first ascent was six hours.

West Arrowhead Chimney (6,800)

Class 6. First ascent December 7, 1941, by Torcom Bedayan and Fritz Lippmann. The large gully immediately west of the Arrowhead terminates in a dark, massive chimney blocked by room-sized chockstones. From an alcove above the first chockstone work up a class 6 crack formed by the huge chockstone and the left (W) wall of the chimney. Higher up the fourth and very difficult chockstone is climbed around its right side. Where the chimney opens up about 300 feet below the last chockstone, climb up onto the left wall of the cleft and traverse upward and to the right on friction holds to the top of the chockstone (direct aid will be required). From this point the remainder of the climb is over easy terrain to the rim of the valley. This difficult climb requires a full day. (SCB, 1942, 134-136.)

Arrowhead (5,800)

South arête. Class 5. First ascent September 5, 1937, by David R. Brower and Richard M. Leonard. This is a spire in Castle Cliffs prominent from Yosemite Lodge. Follow the old Indian Canyon Trail (starts behind the incinerator on the stub road just east of the postoffice) for about 1,200 vertical feet to a point where the trail is about to pass northeast of the Arrowhead. Leave the trail and traverse diagonally upward to the left (NW) over class 2 and 3 forested ledges around the south buttress of the Arrowhead to the deep cleft just west of the pinnacle; this is the West Arrowhead Chimney. Traverse a horizontal ledge back to the right (SE) to a tall Douglas fir at the base of the sharp arête which is followed to the summit. Most of the route is at a high angle but on enjoyably deep holds. Rappel via the route of ascent or into the gully below West Arrowhead Chimney, making the first rappel to the notch. The greatest difficulty on this climb seems to be finding where to start the rope work.

East face. Class 5. First ascent December 1946 by Fritz Lippmann and Anton Nelson. Proceed up the gully at the foot of the deep East Arrowhead Chimney to a horizontal tree-covered ledge on the left (W) side of the chimney. The first pitch, and the most difficult, leads directly up from the ledge in a high-angle open chimney on the east-facing wall; this open chimney narrows down to a closed chimney which leads to the south arête, where the usual route (one pitch) is followed to the summit. Either Arrowhead route is an all-day ascent and provides some of the most enjoyable climbing in the valley.

Royal Arches (5,400)

Class 6. First ascent October 9, 1936, by Kenneth Adam, W. Kenneth Davis, and Morgan Harris. Plan for an all-day ascent. This is one of the most enjoyable routes in the valley, providing all varieties and difficulties of climbing technique. Proceed along the trail a little beyond the base of the Royal Arch Cascade, head up toward the wall, and climb a moderate class a crack. Traverse diagonally upward to the right (E) along the steps of a broad ledge, then up a steep, open chimney, very smooth and difficult. From a broad sandy ledge a short friction lead brings one to easier pitches, where small ledges may be ascended until they give out on a smooth face. Here, a rope traverse to the left (W) leads to a narrow ledge, which widens out during an 80-foot traverse to the west. A jutting rib interrupts the ledge and is passed by another rope-traverse from a small tree above. This brings one to the Rotten Log, bridging a wide chasm. From the top of the log climb directly upward, keeping generally to the left. A few hundred feet of moderate climbing brings one to the final friction traverse, which leads over (left) to the Jungle, or source of the Royal Arch Cascade. Descent to the valley floor can be made by rappel if one is careful to follow the route used for the ascent, or by traversing along the rim of the valley (E) to North Dome gully (see Washington Column). It is possible to avoid use of the Rotten Log by a class 6 lead upward and to the left of the trunk.

Washington Column (5,912)

Lunch Ledge (5,000). Class 4. First ascent September 2, 1933, by Jules M. Eichorn, Richard M. Leonard, Bestor Robinson, and Hervey Voge. From the base of the chimney separating the Column from the Arches, traverse right around the corner onto the 65° face. Follow a series of ledges and cracks of difficult class 4 climbing diagonally upward to the right (NE) to a drop-off, where a cairn will be found. This point is about 800 feet above the talus and 400 feet to the right (E) of the starting point. From here climb directly up 75° cracks and chimneys, interrupted by oak-grown ledges, for a distance of about 200 feet. The final vertical crack, known as Riegelhuth Chimney, leads to a rather inconspicuous three-foot ledge without vegetation which traverses the face horizontally about 50 feet to the left (W). This is the Lunch Ledge and is at the end of the class 4 climbing. The routes split here and are class 5 above. Many climbers enjoy the excellent climbing to this point with almost unexcelled rappelling as a climax; the Lunch Ledge and the routes above are undoubtedly the most popular roped climbs in the valley.

Piton traverse. Class 5. First ascent May 31, 1935, by Morgan Harris, Richard M. Leonard, and jack Riegelhuth. At the west end of the Lunch Ledge traverse diagonally upward to the left (W) on an avalanche-polished 65° face with very small and rounded holds. Pitons should be placed for protection but are not needed for direct aid. At the top of this 75-foot pitch climb upward and somewhat to the right to a small chimney. From its top enter the main gully west of the column and continue via the gully to the brush covered sand slopes leading to the summit. The only impediment in the gully is a short waterfall which may cause considerable difficulty in the wet season. This is the easiest of the routes leading upward from the Lunch Ledge.

Fat Man Chimney. Class 5. First ascent May 26, 1934, by Virginia Greever, Randolph May, and Bestor Robinson. Directly from the Lunch Ledge ascend the chimney which leads diagonally upward and to the right. The chimney is on a 70° face and the upper portion is only 15 inches wide and of a crumbling nature. From the top continue diagonally to the right into a specious alcove. From this traverse horizontally back to the left (W) for 200 to 300 feet and continue on into the main gully.

Direct route. Class 5. First ascent August 17, 1940, by DeWitt Allen, John Dyer, and Robin Hansen. From the alcove above Fat Man Chimney traverse right (E) around the corner and up a friction pitch to the base of a small scree slope. This leads to a spectacular chimney, prominent from the valley floor, which is 200 feet high and divided in two sections. From deep within the chimney proceed directly up and either behind various chockstones or out toward the front to the second half which is relatively open and which steepens near the top. From here work left (W) and then ascend a small chimney to a large platform. Continue left around the corner, then ascend another chimney into a cave and out its window. Continue up on the scree to the base of the final cliff. From the base work onto a sloping alcove by using a large embedded flake. After gaining a second ledge, cross an open chimney and traverse upward (E) to a tree-covered platform. Climb up a short cleft, then halfway up a right-angle chimney. At this point traverse (W) across a smooth face to the summit slope of the Column. This route is considerably longer than the other two routes above the Lunch Ledge.

The descent from Washington Column is best made by contouring from the summit (E) into the gully across from the Column and following down the gully to easy ledges and scree slopes which lead toward Tenaya Creek. The final cliffs may be by-passed by going to the right (W).

Dinner Ledge (5,250). Class 6. First ascent April 30, 1952, by Dave Dows and Don Goodrich. From Indian Caves climb talus until just under the vertical upper face of the Column and just east of the region of great overhangs. Work to the left (W) along a grassy bench as far as possible and up loose rock ledges to the left. A foot-wide, eight-foot high crack leads toward a large flat ledge with small trees, about 100 feet higher, and a class 6 pitch proceeds up the left side of three cracks to a large pine. From here varied climbing continues to the Dinner Ledge, which is the top of a buttress, and the highest ledge of the south face of the Column.

Watkins Gully (6,750)

Class 6. First ascent September 1946 by Robin Hansen, Fritz Lippmann, and Rolf Pundt. Approach the deep gully immediately west of Mount Watkins from the east up a prominent ramp directly below the Watkins Pinnacles, pass through a unique tunnel, and attain the gully proper via a delicate pitch. From here there is not much chance of getting off route as the gully walls are nearly unbroken and vertical. The main obstacles are overhanging chockstones, one of which requires direct aid. Water in the gully will increase difficulties considerably. This is an all-day climb.

Watkins Pinnacles

Middle Pinnacle. Class 6. First ascent December 1946 by Alfred Baxter and Rupert Gates.

Upper Pinnacle. Class 6. First ascent May 1947 by Alfred Baxter, Rupert Gates, and Ulf Ramm-Ericson.

These pinnacles jut out from the southwest shoulder of Mount Watkins, and are best seen from the Snow Creek trail just below the falls. After climbing to the summit of Mount Watkins descend the southwest shoulder until fixed ropes become advisable. A 300-foot rappel from a tree brings one to another tree on the edge of the south face overlooking the notch which separates the pinnacles from the wall. Rappel from this point into the notch. Enough rope should be carried so that these last two rappels may be left as fixed ropes. One short pitch from the notch leads to the saddle between the pinnacles from which point ascents of the Upper and Middle Pinnacles can be easily made. Pitons are necessary on the Upper Pinnacle. Thus far the lowest pinnacle, about 150 feet below the notch, has repeatedly turned back attempts to reach its summit. Its walls are overhanging and quite smooth. One or two expansion bolts have already been placed.

Tenaya Canyon (4,000—8,000)

Class 3. First recorded traverse 1866, by Joseph Farrel, Alfred Jessup, and Mr. Stegman. Although a traverse of the canyon involves no difficult climbing, the problem of route finding arises often. Ropes should be carried, but are not always needed.

High water routes. At Inner Gorge (opposite Quarter Domes) ascend either side of the canyon until about 250 feet above the stream. From his point work eastward and traverse diagonally down into Lost Valley, at the upper end of the gorge. Routes involving talus, smooth granite, and brush may be discerned alongside Pyweack Fall, at the head of Lost Valley. These lead to Waterwheel Valley, and no further difficulty is encountered on the way to Tenaya Lake. The south side of the canyon has perhaps more brush than the north throughout the climb.

Low water. The low water traverse of Tenaya Canyon, which can be made in late August or September, should appeal more to rock climbers since there is more rock-climbing and less bushwhacking. From the lower end of the Inner Gorge, the course of the stream may be followed to the first waterfall where the stream divides around a chockstone. Below this a detour to the left (N) is made, and a scree-covered ledge some 50 feet above the stream is followed until well past the fall. Returning once again to a point on the stream marked by a split rock through which lies the only easy route, climb approximately 150 feet above on brush-covered slopes until it is possible to continue eastward into lower Lost Valley over a series of narrow, exposed ledges, including Initial Ledge, which bears the dates of the annual trips made by S. L. Foster, from 1909 to 1937.

Clouds Rest (9,929)

North face. Class 5. First Ascent August 16, 1952, by Jack Davis and Dick Long. From Mirror Lake follow Tenaya Creek for about a mile. Gradually work upward and eastward toward the north face making use of a series of gullies and ledges and arriving at a point about three quarters of a mile west of the summit and several hundred feet below the south rim. Some bushwhacking and one or two class 4 pitches will be encountered. Here is a junction of routes: one leading (SW) to the Quarter Domes, the other continuing left (E) a considerable distance to the north face via a large class 2 ledge until the route is blocked by a great couloir. A series of ledges of varying difficulty circumvents the couloir and terminates at the top of a large sloping face. From here there seem to be several easy routes leading to the rim slightly west of the summit. This is definitely an all-day climb.

Quarter Domes (8,276)

From Tenaya Canyon. West of the Domes. Class 2. First ascent June 11, 1939, by R. S. Griswold, C. A. Harwell, and Julian Howard. From 500 feet above the mouth of the Tenaya Creek Inner Gorge (see Tenaya Canyon) a broad ledge ascends 1,200 feet to the southwest, terminating in a gully heading just west of the Domes. When free of snow, the route is a moderate climb, complicated principally by dense brush. The first ascent began within the Gorge.

From Tenaya Canyon. East of the Domes. Class 4. First ascent August 16, 1952, by Norman Goldstein and George Mandatory. From Mirror Lake follow the Clouds Rest-North Face route to the route junction. From here a prominent class 2 ledge with a 20° slope leads right (SW) directly to the rim, emerging about a half mile from the trail to Clouds Rest via flat country. The Domes are passed on the right.

Ahwiyah Point (6,925)

From the west. Class 3. First ascent obscure, probably by Charles W. Michael. First recorded ascent, September 3, 1933, Richard G. Johnson, Jack Riegelhuth, and Hervey Voge, who climbed from Mirror Lake. It is most easily climbed from above.

Northeast gully. Class 3. First recorded ascent, August 5, 1937, David R. Brower and Morgan Harris. Correct route finding is essential. Ascend avalanche debris below the gully to easy slabs leading to a 30-foot waterfall. Pass this over easy ledges to the left (E) and enter the gully proper, from which point it is impossible to leave the route. The ascent is greatly complicated by water in the early season.

Diving Board (7,500)

From Little Yosemite. Class 2. First ascent unknown but probably early. From Lost Lake proceed through brush toward the 7,000-foot mark on the map at the base (SW) of Half Dome. An easy route can be worked out near the right (E) end of an intricate maze of ledges separated by 45° massive granite slopes. If the lucky ledge is found, a horizontal traverse (W) will bring one to easy sand slopes. Follow these, as directly as convenient, to the base of the Dome and skirt the cliffs to avoid brush. This route is usually too intricate to find when going toward Little Yosemite. Unless the party is equipped with a rappel rope, it is safer to plow through heavy brush and skirt the cliffs on the west.

From Mirror Lake. Class 3. First ascent by Charles W. Michael prior to 1927. Follow the Mirror Lake-Half Dome route as far as the great face of Half Dome. Until July in a normal year an ice axe is advisable in ascending the 400-foot, 40° snow couloir below the west end of the overhang. At the head of the couloir traverse upward on a 6-foot, sloping, scree-covered ledge overhanging 1,000 feet of space.

West Buttress. Class 4. First ascent May 29, 1938, by Kenneth D. Adam and W. Kenneth Davis. Starting from Mirror Lake ascend a brush-covered gully for 2,500 feet. Above, climb the broken face of the West Buttress to the Diving Board. There are probably several possible routes here.

Half Dome (8,852)

From Mirror Lake. Class 3. First ascent unknown. The initial barrier is a 200-foot cliff stretching along the entire base. This can be passed by an easy gully at the west end. After reaching the ledge on top of the cliff, traverse east to polished, massive granite at an angle of 35° to 40° rising west of the water course. The principal problem is to avoid brush without getting onto rock of too high an angle. At the base of the great face there is an easy route eastward to the Clouds Rest saddle. There is water at the base of this face in all seasons. After reaching the saddle the Dome may be climbed by means of the trail and cable.

By trail and cable. Class 2. First ascent October 12, 1875, by George G. Anderson. From Nevada Fall a trail leads up to the east side of Half Dome, where parallel cables at waist height are placed in the summer season and greatly facilitate the ascent of the east slope of the dome. The history of this route is interesting. After three attempts by other parties, Anderson was able to make the ascent by drilling holes for iron spikes. A detailed account of a somewhat later climb has been given (SCB, 1946, 1-9). The present one-inch steel cables, with wooden foot-rests placed at ten-foot intervals on the 46° slope, make the 450-foot climb up the dome entirely safe for those not troubled by height. Rubber soles are essential.

Without the cable. Class 4. First ascent in 1931 by Judd Boynton, Warren Loose, and Eldon Dryer. This is purely a problem of adequate friction on the 46°, moderately rough granite. Ascents have been made on both sides of the cable.

Southwest face. Class 6. First ascent October 13-14, 1946, by Anton Nelson and John Salathé. The route starts at the base of the converging vertical breaks in the west face just to the right of the two conspicuous pines about 100 feet up. Three hundred feet up one encounters a crack running straight up 300 more feet, without feasible alternatives, almost to the great overhang which circumscribes the climb on the left (N). From the top of this crack rope-traverse 25 feet to the right and climb up another crack that contains a deep diagonal overhang which is passed on the right. Above, friction work on easier slabs brings one to the summit. Descend either by the cable or rappel somewhat north of the climbing route. The first ascent took 20 hours and used 150 pitons (SCB, 1946, 120-121).

LeConte Gully (5,925)

Class 4. This is the gully just north of Grizzly Peak. It was probably climbed by Hutchings as early as 1869 in an attempt on Half Dome. It is class 2 all the way except for one 25-foot pitch. Follow the Sierra Point trail until it definitely leaves the gully and turns south. Follow up the broad gully on easy scree for about 750 vertical feet above the trail. Here a 100-foot, 45° pitch can be passed on a rock-garden ledge on the right (S). This leads to a pocket out of which one climbs the short class 4 pitch at the upper left (N) corner to easy climbing above.

Grizzly Peak (6,219)

From Little Yosemite. Class 2. First ascent 1885, by Charles A. Bailey. From Little Yosemite proceed to the notch at the head of LeConte Gully (see route to Diving Board). Follow the south side of the ridge to the summit.

South arête. Class 3. Two gullies ascend the south wall of Grizzly Peak. The easternmost and most precipitously walled of these is class 5. The west side of the arête between them, partly covered with brush, may more easily be ascended to the first notch east of Grizzly Peak. To approach this route, leave the Vernal Fall trail below its junction with the abandoned Anderson trail.

Southwest arête. Class 4. First ascent unknown. Take the trail to Sierra Point. From there ascend a minor gully, a short rock pitch, and ledges to the arête. Follow the arête, turning right or left where it becomes difficult, to the summit.

West face. Class 5. First ascent June 1942, by Dick Houston and Ralph McColm. Follow the Sierra Point trail until level with Sierra Point and then proceed left (NE) over brushy ledges until a point is reached where further traversing would involve difficult climbing. From this point easy climbing up several open chimneys and through thick brush brings one to the crux of the climb, a large open chimney 150 feet long and requiring pitons for protection. Easy climbing then leads to the summit. Several routes are possible on this broken face and they provide good climbing in the sun for cold days.

South gully. Class 5. First ascent June 7, 1938, by David R. Brower and Morgan Harris. The abandoned Anderson Trail to Vernal Fall may be followed high into the talus below the south gully, the easternmost of the two gullies ascending the south wall. Ascend 250 feet, zigzagging over oblique, intersecting ledge planes. Just west of the gully where the ledges run out, rope-traverse down and east to a narrow ledge which continues its narrowing course to the northeast, returning at an angle of 40° to the gully. The lead becomes increasingly exposed as one nears the gully. The gully may be ascended without difficulty to a cave, which is passed on a smooth, high-angle face to the right. The upper gully rapidly opens out into easier climbing at a diminishing angle, but parties should remain roped until well past the apparent exposure. A moderate scramble brings one to the second notch east of Grizzly Peak, where the usual ducked route west of the summit ridge may be followed to the top. Any of the Grizzly Peak routes can be completed in half a day.

Mount Broderick (6,705)

Class 3. First ascent obscure, but probably by James M. Hutchings before 1869. A friction climb up the smooth granite on the northeast ridge. A rope is sometimes needed on one pitch.

Mount Starr King (9,081)

Northeast side. Class 4. First ascent August 1876 by George B. Bayley and E. S. Schuyler. From the top of 30° slabs at the northeast base of the dome traverse diagonally upward to the right (W) on 43° rough granite for 40 feet to a stance on a small ledge. Climb directly up, following a grass-filled two-inch crack, and proceed along and over the edges of two-foot exfoliation shells to the summit.

Southeast saddle. Class 4 (minimum). First ascent August 23, 1877, by George G. Anderson, James M. Hutchings, and J. B. Lembert. An easier route than from the northeast, but still requiring care in friction climbing along and over exfoliation shells. In climbing trend gradually to the left (W).

Panorama Cliff (6,250)

Class 5. First ascent October 12, 1936, by David R. Brower and Morgan Harris. From the Nevada Fall trail at the base of Grizzly Peak an immense diagonal trout-shaped scar may be discerned as the source of one of the largest recent Panorama Cliff rockslides. The route follows, with slight variation, a line drawn from the highest talus of the north face of the cliff, passing immediately above the scar, and continuing upward and to the right (SW) into the broken and forested upper face. The first pitch leads to the shelf with a large Douglas fir. From here continue upward and to the right. One should be on the lookout for large loose blocks when climbing above the scar. From here it is possible that a number of routes may be followed. Although the brush and scree slopes may not seem to require consecutive climbing, the considerable exposure justifies it. This is one of the longest one-day climbs in the valley.

Illilouette Fall (5,816)

West side. Class 4. First ascent probably by Charles W. Michael in the twenties. First recorded ascent September 3, 1933, by Marjory Bridge, Lewis F. Clark, and William Horsfall. There is probably more than one feasible route up the broken face west of the fall.

Glacier Point (6,750)

East face. Class 5. First ascent May 28, 1939, by Raffi Bedayan, David R. Brower, and Richard M. Leonard. This route follows close to the first watercourse south of Glacier Point, directly opposite Sierra Point. From the Fish Hatchery follow the pipe line road to the settling basin. Turn right and follow a small stream to the cliffs. A chimney just to the left (S) of the stream constitutes the route all the way. Once the first high-angle diagonal chimney is passed, the route abounds in bomb-proof belay positions and well-watered rock gardens (in season).

Glacier Point Terrace (5,500)

Class 5. First ascent June 24, 1937, by David R. Brower and Morgan Harris. From an elevation of about 4,800 feet on the Ledge Trail traverse diagonally (E) along a broken connecting ledge under the great overhang toward the terrace that forms the ultimate base of the Firefall. The east end of the traverse is quite exposed and should be well protected. A small tree serves as a splendid belay for a final delicate traverse ending in an open chimney that leads to the terrace. It is interesting here to observe the variety of debris that has come over the cliff through the ages. Several attempts to leave the terrace by an upper route have so far been blocked by difficulty and have been subject to the gratuitous hazard of falling miscellany dropped by tourists on Glacier Point—golf balls, fountain pens, beer cans, and rocks. The rocks can be heard but not seen as they pass by.

Potato Masher (5,750)

Class 5. Rappel rope necessary. First ascent July 28, 1951, by J. George Maring, Don Currey, Don Sorensen, and John Marten. From the switchbacks of the Glacier Point Four Mile Trail between the 5,500- and 6,000-foot contours, an easy traverse eastward brings one to a notch above a short arête (contour circle 5,750) lying nearly due north of Union Point. This arête culminates to the north in the Masher, separated by its col from two other pinnacles forming the crest. The first pinnacle is passed on the left (W) in easy climbing which brings one to a lofty amphitheater south of and below the second pinnacle, which is passed to the east. From the north side of its summit rappel 40 feet to a chock-stone platform at the base of the col leaving the rappel in place for the return. A class 5 route lies up the southeast corner of the Masher; all other sides overhang. On the return the second pinnacle is easily regained via the fixed rope. Time for the original ascent was three hours.

Sentinel Rock (7,000)

South notch. Class 3. First ascent obscure, but it was a popular tourist ascent by 1870. Approach on the Four Mile Trail and ascend the gully heading in the notch just south of the summit.

Circular Staircase. Class 5. First ascent May 1940 by David Brower and Morgan Harris. Traverse over from the Four Mile Trail on easy scree-covered ledges to the Tree Ledge directly under the north face. Descend an exposed route 70 feet to the broad, sloping ledge crossing the west face of the massif. Follow the ledge to within 50 yards of its terminus in a watercourse and ascend 150 feet. There follows a 120-foot lead requiring pitons up a shallow chimney to the next broad ledge. A traverse back to the watercourse connects with an open gully leading to the notch behind the summit. Ascend through brush to the top.

Northeast bowl. Class 6. First ascent June 12, 1948, by Anton Nelson and John Salathé. From tree ledges below the north wall traverse (E) around and down into the bowl. The route consists of vertical cracks and open chimneys, starting near the middle of the bowl and working toward the left (E) side. One emerges on top of the ridge through a needle’s-eye at the top of an overhanging chimney, followed by a very rotten chimney and a second needle’s-eye. Relative to Yosemite standards, rock on this climb is rotten in the extreme; therefore, the route is advisable only for the cautious, experienced climber. It would be a poor place to be benighted.

North face. Class 6. First ascent June 30 through July 4, 1950, by John Salathé and Allen Steck. (SCB, 1951, I-5.) The wall can be divided into parts of somewhat equal distance: Tree Ledge to the top of the prominent buttress, and from the latter to the summit. Route of first ascent leads up right (W) side of the buttress to the tree-studded ledges of its top (two days). Continue up the headwall with aid of expansion bolts for a full rope length and traverse left (E) into steep cracks beneath the Great Chimney (one day). Follow this chimney for the remaining distance (about 500 feet) to the summit (one and one-half days). Other ascents should require less time as the expansion bolts were left in place.

Lost Brother (6,625)

Class 5. First ascent July 27, 1941, by David R. Brower and L. Bruce Meyer. The semi-isolated buttress across the valley from the Three Brothers and well up Taft Arête is known as the Lost Brother. The best approach is to ascend the avalanche gully heading between Taft Arête and Taft Point to a point in line with the Lower Cathedral Rock and the massive white-scarred overhang on the north face of the Lost Brother, and thence contour east to the base of the broad, sloping, brush-and-tree-covered ledge under the white overhang; ascend this ledge to the highest point readily accessible at its eastern end. Here the first pitch involves a shoulder stand and leads up a narrow crack to the top of a 30-foot block. Two fine chimneys and some intervening cracks bring the climber to the Douglas fir ledge 600 feet below the top. From its southern end a higher alcove may be reached, and finally the notch in Taft Arête, by climbing an exposed face, an open chimney, and an easy ledge. The summit is attained by proceeding directly from the notch.

Phantom Pinnacle (5,900)

Class 6. First ascent September 9-10, 1950, by William W. Dunmire and Robert L. Swift. This 400-foot shaft lies on the south side of the Cathedral Spires Buttress and is therefore hidden from most view spots in the valley. The climb from the base is made on the upper side and ascends the vertical cracks formed where the pinnacle makes a right angle with the cliff; the route is obvious to the notch. From the notch cross above the chockstone and ascend to the summit on the northeast side of the spire. The first ascent took two days of climbing.

Harris’s Hangover (6,250)

Class 6. This is the northeast chimney of the Spires Buttress. First ascent August 13-14, 1949, by Oscar A. Cook, William W. Dunmire, and Robert L. Swift. A prominent chimney divides the sheer buttress immediately southeast of Cathedral Spires. The ascent is made entirely within this chimney and involves a series of overhanging chockstones. The largest of these, several hundred feet up the chimney and clearly visible from the valley floor, requires direct-aid pitons and should be climbed on the right-hand (W) wall, from a start deep inside the chimney. Beyond this chockstone the difficulties lessen considerably. The first ascent took 12 hours. This is an excellent climb for hot weather; the entire route is in shade.

Church Tower (5,500)

From the southwest notch. Class 5. First ascent May 30, 1941, by Bill Horsfall, Dick Houston, Ed Koskinen, and Newton McCready. Ascend the broad talus chute east of the Church Tower to the base of the notch between it and the Lower Cathedral Spire. Climb the broken face to the right (E) of the notch to a short chimney and traverse farther right (E) to a large tree. Attain the east arête via a short, deep chimney and continue along the arête, crossing a deep notch to the small summit tower, which may be climbed from the north over a smooth 50° face or by circling farther right north around the tower to the back (W) side. This is the shorter and easier of the two very popular class 5 routes on the Church Tower.

East arête. Class 5. First ascent October 12, 1935, by Kenneth Adam, Olive Dyer, and Morgan Harris. Several hundred feet below and to the right (NE) of the notch (see above) an easy tree-covered ledge leads right to the northeast corner. From here ascend a 60-foot open chimney, the most difficult pitch on the climb. Walk along a “rue de bicyclette” on the southeast side of the steep arête just below the crest to a large tree where the southwest-notch route is joined. Descend from the summit by rappelling to the notch.

North wall. Class 6. First ascent June 1, 1946, by Dewitt Allen, Fritz Lippmann, Anton Nelson and John Salathé. Start at the highest talus just under the north side of the overhanging summit block and work up to the left (E) toward the northeast ridge. Proceed upward on the east side of the north face by means of a piton ladder or a long and exposed open chimney. Above, the climbing is mainly class 4 and 5 until a junction is made with the original route to the summit along the east arête.

Lower Cathedral Spire (5,903)

Main Ledge. Class 4. First ascent November 4, 1933, by Jules M. Eichorn, Richard M. Leonard, and Bestor Robinson. Ascend talus chutes east of the Spire to a point about 150 feet down from the notch between the Spires. Starting here, at a large tree, climb through brush and trees onto a small ledge which leads to a shallow chimney dropping sharply to the right (S). Climb straight up the left (W) buttress of the chimney about 40 feet and traverse to the left (W) past an airy step. From here a 200-foot open chimney leads up to the main ledge. There are at least two other variations in the lower part of this climb. One starts higher and closer to the notch on a difficult 75° face, while the other starts lower down from the notch in an open chimney. Above the Main Ledge difficulty increases considerably, but the climb that far is enjoyable and instructive for its own sake.

Right-hand Traverse. Maximum class 5. First ascent May 30, 1948, by Raffi Bedayn, Paul Estes, Jerry Ganopole, and Roy Gorin. This variation may be used as an alternative to a direct ascent of the Flake. It minimizes the amount of direct aid necessary, substituting difficult class 5 climbing. From the east end of the Main Ledge at the base of the Flake Pitch traverse down and right, using a sling in a piton for support until the rock itself again provides adequate holds. The traverse ends at a small shelf twenty feet east of the starting point. From here the exposed route leads directly up on small holds, but is fortunately provided with cracks for protection by pitons. Two long pitches above its inception, this variation joins the following route on the wide ledge above the Flake.

Descent from the Spire involves an overhanging toy-foot rappel over the Flake, so a check of rope length is important. Average time of ascent for either route is about 6 hours.

Flake Pitch. Class 6. First ascent August 25, 1934, by Jules M. Eichorn, Richard M. Leonard, and Bestor Robinson. (SCB, 1935, 107.) From the right-hand (E) end of the Main Ledge a huge granite flake can be discerned directly above. From a shoulder-stand ascend the 83° face to just under and to the left (W) of the Flake. The usual technique is to lasso the horn of the Flake with sling rope, anchor the sling rope to carabiners, and mount the Flake using the fixed rope. Care should he taken in placement of pitons to avoid rope drag, and for this reason double-rope technique is preferable. Above, traverse the wide ledge around the corner to the right (E) into a chimney which leads upward. Continue to the summit via easy pitches. The Flake has been ascended at least once without lassoing the horn.

Higher Cathedral Spire (6,114)

Southwest face. Maximum class 5. First ascent April 15, 1934, by Jules M. Eichorn. Richard M. Leonard, and Bestor Robinson. (SCB, 1934, 34-37.) The flood channel near the Cathedral Rocks will be found an easier approach than the forest. Starting from upper scree slopes south of the Spire, climb a short crack to the wide ledge known as First Base. There a difficult overhang 20 feet above the belayer must be surmounted in an open chimney, and a delicate traverse left (W) is required around the corner to the Bathtubs, remarkable solution pockets on a 77° face. A further traverse of about 15 feet to the left (N) brings one to an expansion bolt to protect a difficult step into a high-angle crack on the west face. Follow this crack diagonally upward to an alcove known as Second Base. Above this rope-traverse around the corner to the left (N), and then climb up another chimney on excellent holds. From 20 feet higher another traverse to the left onto the north face brings one to Third Base. Follow this prominent ledge (right) south around the west and south (or north and east) faces to an easy chimney up the summit block on the southeast corner. Although direct aid has been used with two of the pitches on most ascents, the Higher Spire has been climbed several times entirely class 5. Average time of ascent is most of a day.

South face. Class 6. First ascent August 18, 1948, by Fletcher Hoyt, William Hoyt, and Allen Steck. From First Base the route leads to the right in a delicate traverse and then upward in a broken chimney and over a bulging chockstone. Around farther to the right is a thin ledge which provides an easy route to a welcome platform 25 feet above. From the platform a class 6 crack leads upward to the left, ending below a flake, directly over and 150 feet above the First Base ledge. Ascent of the easy chimney between the flake and the wall brings one to the ledge leading to the base of the Rotten Chimney (Second Base). The south face route, however, follows a vertical crack 15 feet to the right (E) of the base of the talus notch. At the top of this difficult 80-foot crack a traverse on tension enables the leader to reach a break in the vertical face which ends in a sloping shelf. From here a short closed chimney leads to another ledge and a 45° trough ends at the base of the summit block. The first and only ascent to date took a full day and used 41 pitons, 34 for direct aid.

Cathedral Chimney (6,300)

Class 5. First ascent October 11, 1936, by David R. Brower and Morgan Harris. Moderate continuous climbing leads up the floor of the spectacular broad chimney between the two highest Cathedral Rocks to the base of a 150-foot, 70° pitch in the upper portion of the gully. This may be climbed by ascending the face a few feet to the right (N) then traversing left to easier rocks. Continue for several hundred feet to an overhanging chockstone, which, when dry, may be climbed with the aid of a small tree growing near the top. A more difficult variation, over smooth slabs to the right (N) of the chockstone, has been used in the early season, when the chockstone becomes a miniature waterfall. The rest of the gully is easy.

Penny Pinnacle (5,000)

Class 5. First ascent April 1946 by Torcom Bedayan and Fritz Lippmann. Approach the pinnacle attached to the lower east face of Middle Cathedral Rock via the talus gully to the south. Two pitches are required to reach the notch, and a shoulder stand is helpful to get onto the ledge leading to the summit pitch.

Middle Cathedral Rock (6,551)

Kat Walk. Class 4. First ascent September 1929 by Ralph S. Griswold. Moderate continuous climbing leads up the great chimney between the two higher Rocks to a 70-foot cliff. From the base of this cliff follow a brush-covered ledge out on the face to the right (NE) for several hundred feet, thence up steep ledges and pitches to the summit. Descent via this route or, more easily, by the Gunsight. To reach the Gunsight descend (W) to Bridalveil Creek, keeping to the left (S) of the smooth slabs, until an easy traverse right (N) can be made to the Gunsight notch.

Northwest buttress. Class 5. First ascent April 18, 1953, by Jack Davis, Marjorie Dunmire, William Dunmire, Richard Houston, Richard Long, and Dale Webster. From the top of the Gunsight (see below) a notch may be discerned on the Middle Cathedral Rock skyline below and to the right (W) of the summit. The route generally follows a line of several trees up the broken face to this notch. Above and about 100 yards southeast of the Gunsight notch a brushy crack leads to a large Douglas fir. From here continue directly upward several hundred feet until along-side of a vertical open chimney on the right. Lack of holds may require the use of a direct-aid piton in one place below the chimney. Traverse right (S) into the chimney, ascend it, and continue upward to easy scrambling leading to the summit. The ascent can be made in part of a day.

Gunsight (5,200)

Class 4. First ascent obscure and probably early. This gully lies between the Middle and Lower Cathedral Rocks. The large chockstone near the top is best passed to the left (S) on sound, angular holds; a rope is desirable here. The Gunsight gully offers an interesting short rock scramble to attractive lunch spots on Bridalveil Creek above the fall and to climbs on Middle Cathedral Rock or the Leaning Tower.

Lower Cathedral Rock (5,610)

Northwest face—Overhang bypass. Class 5. First ascent June 1, 1952, by William Dunmire, Richard Long, William Long, and Edward Robbins. Two overhanging blocks within 100 feet of each other may be discerned part way up on the northwest face. For both routes, roped climbing starts from below the easternmost of the two overhangs. From the highway on the east side of Bridalveil Creek work up forested class 2 ledges to a gully heading diagonally upward and to the left (E). This gully may be ascended to just below the 160° overhang extending 8 feet from the face. A short, touchy traverse left of the overhang leads to a 45° chimney veering eastward. At the top of the chimney climb upward from a bushy ledge and then right (W) on a new ledge. Where the ledge terminates, ascend the partly broken but very exposed face. Above, traverse left again into an open gully which overhangs above. Friction climbing in the gully leads to an alcove on the right side. This alcove can also be attained by ascending a short open chimney just before reaching the gully, but this variation seems to require a direct-aid piton. From above the alcove continue via an easy pitch or two to the tree-covered slopes above.

Northwest face—Overhang route. Class 6. First ascent September 7, 1935, by Doris F. Leonard, Richard M. Leonard, and Bestor Robinson. Follow the route described above to below the 160° overhang. From a half-inch ledge on a 70° face immediately under the overhang a shoulder-stand (with pitons supporting the second man) enables the leader to ascend a vertical chimney to the right of the overhang to a cave beneath a second overhang 15 feet above the second man. Traverse to the right (W) on almost inadequate holds and reach a large platform above the upper overhang. Enjoyable climbing at 85° on remarkably fine holds then brings one to an easy walk to the summit. Either of the two northwest face routes can be accomplished in part of a day. Descend via the Gunsight.

Leaning Tower (5,863)

Class 4. First ascent probably by Charles W. Michael, date unknown. Approaching Bridalveil Creek by the Gunsight (or any of the more difficult routes leading to the top of the fall), traverse over moderate friction climbing to the notch south of the Leaning Tower. From here friction climbing continues over varied routes to the summit, with the higher angle of the slope indicating use of the rope in consecutive climbing.

Leaning Chimney (5,675)