| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Geologic Story of Yosemite > A view from the top—Mount Hoffmann >

Next: Geologic overview • Contents • Previous: Yosemite country

VIEWS FROM MOUNT HOFFMANN. A, Westerly view down wooded slopes toward California’s Central Valley. B, Northerly view including snow-patched Sawtooth Ridge and Matterhorn Peak on Skyline at north edge of the park. Photograph by Tau Rho Alpha. C, Easterly view, with May Lake in foreground and Tenaya Lake to right in middle distance. Tuolumne Meadows is in wooded area to left, and Mount Dana is highest summit on skyline beyond. D, Southerly view toward Clouds Rest in late spring, with Mount Clark on left skyline. Half Dome at far right center displays its northeast shoulder, in contrast to its oft-pictured profile from Yosemite Valley’s floor. Photograph from National Park Service collection. (Fig. 4)

|

||

| A | [click to enlarge] | |

| ||

|

||

| B | [click to enlarge] | |

| ||

|

||

| C | [click to enlarge] | |

| ||

|

||

| D | [click to enlarge] | |

Of Mount Hoffmann, William Brewer noted in his journal under the date June 24, 1863, that “It commanded a sublime view and the scene is one to be remembered for a lifetime.” In his turn, Josiah Whitney stated that “The view from the summit of Mount Hoffmann is remarkably fine.”

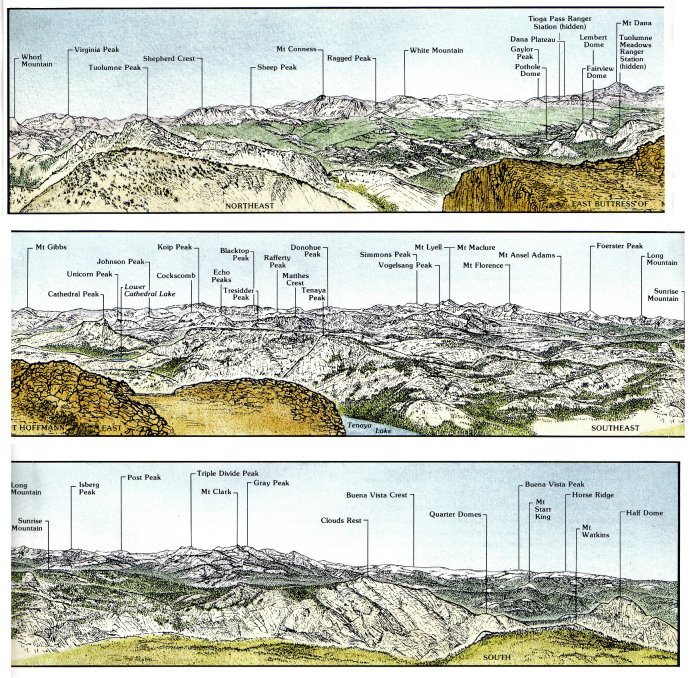

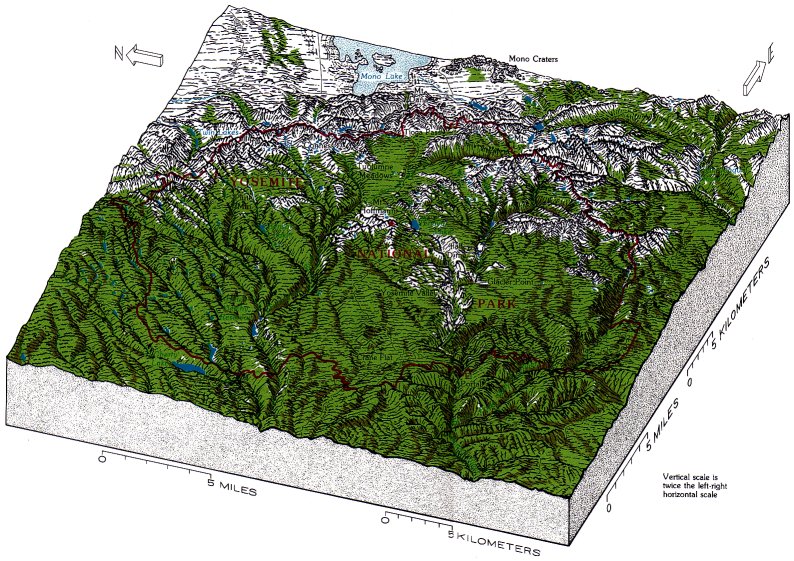

The view from Mount Hoffmann is, indeed, remarkably fine. This peak is in almost the exact center of Yosemite Park (fig. 4), and from its 10,850-ft summit we can see much of the perimeter of the park, for much of that perimeter consists of high ridges.

Looking westward from Mount Hoffmann, we see timbered foothills disappearing into the haze of the Central Valley of California. As we shift our view northward, we see the smooth contours of the foothills give way along the skyline to pointed and jagged peaks of bare rock in shades of white, red, and gray. A lake-strewn cirque, which fed the Hoffmann Glacier that moved down Yosemite Creek, forms the precipitous north face of Mount Hoffmann itself.

To the east, May Lake—named for Hoffmann’s

wife—is directly below and Tenaya Lake is in the

middle distance, surrounded by sheeted granite walls,

|

The scenic panorama from Mount Hoffmann is a grand introduction to much of the geology of Yosemite. The landforms of Yosemite, like landforms everywhere, reflect the type, structure, and erosional history of the underlying rocks. The different colors—white, red, shades of gray—reflect different rock types. The different topographic shapes—spires, domes, cliffs— reflect different rock structures and erosional histories, especially erosion caused by glaciers. In discussing “how best to spend one’s Yosemite time,” John Muir suggested “go straight to Mount Hoffmann. From the summit nearly all the Yosemite Park is displayed like a map.” For those who wish to take his advice, the summit is about 3 mi from the trailhead south of May Lake, and the elevation gain is about 2,000 ft.

The landscape we see today is largely the result of geologic processes operating in the past few tens of millions of years on the parent rock. But to gain a full understanding of the present landscape, we must go back many tens of millions of years more—to the creation of the rocks themselves. Fragments of geologic history going back hundreds of millions of years can be read from the rocks of the park, and with additional data from elsewhere in the Sierra Nevada and beyond, we can reconstruct much of the geologic story of Yosemite. After more than a hundred years of study, the story is still incomplete. But then, geologic stories are seldom complete, and what we do know whets our curiosity about the missing pieces and allows a deeper appreciation for one of our most spectacular national parks. This volume is an attempt to describe the geology of Yosemite and to explain how this splendid landscape, centered on Mount Hoffmann, came into being.

[click to enlarge] |

|

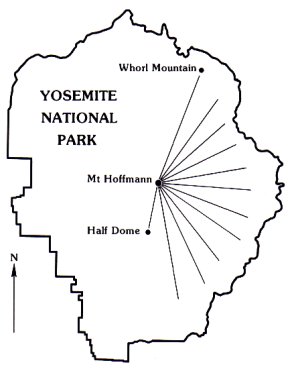

Direction of view from Mount Hoffmann

for panorama. (Fig. 5) |

PANORAMA FROM MOUNT HOFFMANN, encompassing an easterly-facing arc between Whorl Mountain on left and Half Dome on right. (Fig. 5)

[click to enlarge] |

| PHYSIOGRAPHIC DIAGRAM of Yosemite National Park and vicinity. Red dot, centrally located Mount Hoffmann. (Fig. 6) |

[click to enlarge] |

Next: Geologic overview • Contents • Previous: Yosemite country

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/geologic_story_of_yosemite/mount_hoffmann.html