| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Geologic Story of Yosemite > Yosemite country >

Next: Mount Hoffmann • Contents • Previous: Illustrations

For its towering cliffs, spectacular waterfalls, granite

domes and spires, glacially polished rock, and groves of

Big Trees, Yosemite is world famous. Nowhere else are

all these exceptional features so well displayed and so

easily accessible. Artists, writers, tourists, and

geologists have flocked to Yosemite—and marveled.

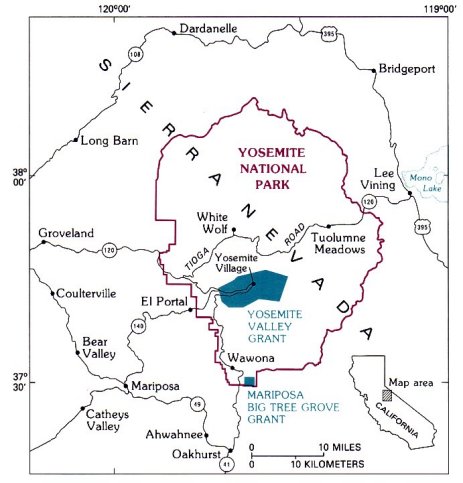

[click to enlarge] |

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK and the original grants to the State of California. (Fig. 1) |

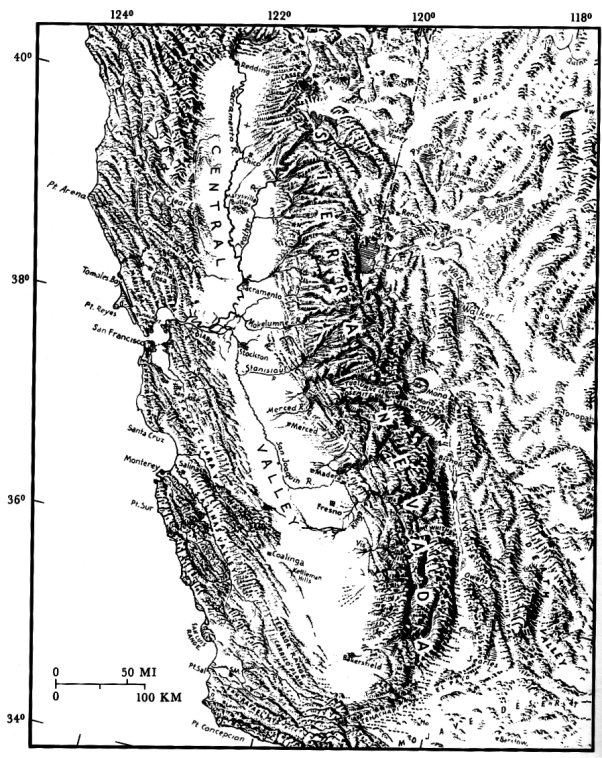

From the earliest days, the Sierra Nevada (Spanish

for “snowy mountain range") was a formidable barrier

to westward exploration

(fig. 2).

Running half the

length of California, it is the longest, the highest, and

the grandest continuous mountain range in the United

| THE SIERRA NEVADA, a strongly asymmetric mountain range with a deep east escarpment and a gentle westward slope toward the broad Central Valley of California. Physiography from landform map by Erwin Raisz: used with permission. (Fig. 2) |

[click to enlarge] |

The Walker party’s journal, recorded by Zenas Leonard, refers to “many small streams which would shoot out from under these high snow-banks, and after pinning a short distance in deep chasms which they have through ages cut in the rocks, precipitate themselves from one lofty precipice to another, until they are exhausted in rain below. Some of these precipices appear to be more than a mile high. * * * we found utterly impossible to descend, to say nothing of the horses. [Continuing westward] * * * we have found some trees of the redwood species, incredibly large— some of which would measure from 16 to 18 fathoms [96 to 108 ft] around the trunk at the height of a man’s head from the ground.” The trees Leonard described could he those either of the Tuolumne Grove or of the Merced Grove, possibly both. The journal was printed in Pennsylvania in 1839, but only a few copies survived a printshop fire, and so this account went unread to many years. [Editor’s note: today historians generally believe the Walker party looked down The Cascades, which are just west of Yosemite Valley, instead of Yosemite Valley itself.—dea]

[click to enlarge] |

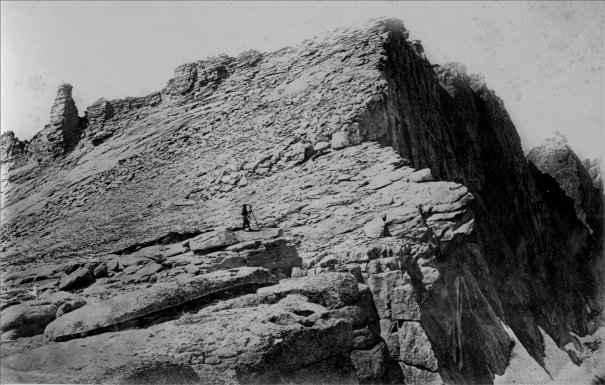

SUMMIT OF MOUNT HOFFMANN. Charles F. Hoffmann, cartographer with the Geological Survey of California, at the transit. Photograph by W. Harris, 1867, first published in J. D. Whitney’s “The Yosemite Book” in 1868. (Fig. 3) |

Yosemite Valley and the giant sequoias remained unknown to the world at large for nearly another 20 years after the Walker party’s discovery, until Maj. James Savage and the Mariposa Battalion of militia entered the valley in pursuit of Indians in 1851. Overwhelmed by the majesty of the valley, one member of the battalion, Dr. Lafayette Bunnell, remarked that it needed an appropriate name. He suggested Yo-sem-i-ty, the name of the Indian tribe that inhabited it, and also the Indian word for grizzly bear. [Editor’s note: For the correct origin of the word Yosemite see “Origin of the Word Yosemite.”—dea.] A year later, giant sequoias were discovered anew in the Mariposa Grove and in the Calaveras Grove north of Yosemite.

The history of further exploration of the Yosemite area, and of the creation of the park itself, were well described by Carl P. Russell (1957). Of particular geologic interest was the excursion of the Geological Survey of California to Yosemite in 1863. After visiting Yosemite Valley, Josiah Whitney, the Director of the Survey, accompanied by William Brewer and Charles Hoffmann, explored the headwaters of the Tuolumne River and named Mounts Dana, Lyell, and Maclure for famous geologists and Mount Hoffmann for one of their own party. In 1867, another party from the Geological Survey of California again ascended Mount Hoffmann, accompanied by photographer W. Harris, who documented the scene with Hoffmann himself at the transit (fig. 3). Observations from these excursions, and additional topographic mapping by Geological Survey of California colleagues Clarence King and James Gardiner, provided the first description of Yosemite Valley and the High Sierra that not only contained reasonably accurate topographic information but also was relatively tree from the romantic exaggeration characteristic of the times. The term “High Sierra,” coined by Whitney to include the higher region of the Sierra Nevada, much of it above timberline, has been used by writers and hikers ever since. Whitney and his party recognized abundant evidence for past glaciation in the High Sierra but failed to recognize the degree to which glaciers had modified the topography, and Whitney ascribed the origin of Yosemite Valley to a “grand cataclysm” in which the bottom simply dropped down.

Indeed, most geologic processes were poorly understood in Whitney’s day, and so numerous conflicting interpretations soon developed regarding the origin of many of Yosemite’s scenic features. The controversy that arose between Josiah Whitney and John Muir regarding the origin of Yosemite Valley reflects this situation. Muir’s observations in the Yosemite Sierra led him to propose that Yosemite Valley was entirely carved by a glacier. However, he overestimated both the work of glaciers and the extent of glaciation, because he believed that ice once completely covered the Sierra to the Central Valley and beyond. Thus, Whitney and Muir held opposing views that were both too extreme, although Muir’s ultimately proved more durable. Finally, partly in response to this controversy, a study of the geology of the Yosemite area was initiated in 1913 by the U.S. Geological Survey, with François E. Matthes studying the geomorphology and glacial geology and Frank C. Calkins the bedrock geology. Matthes’ conclusions, particularly with respect to the relative roles of rivers and glaciers in sculpting the landscape, have held up well, and his lucid descriptions and interpretations have enlightened many a park visitor. In the 50-odd years since Matthes and Calkins completed their studies, we have gained considerably more geologic knowledge of the Sierra Nevada; we have abandoned some of their ideas, but we still build on their pioneering efforts.

Next: Mount Hoffmann • Contents • Previous: Illustrations

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/geologic_story_of_yosemite/yosemite_country.html