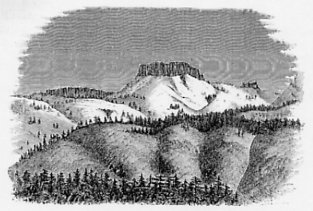

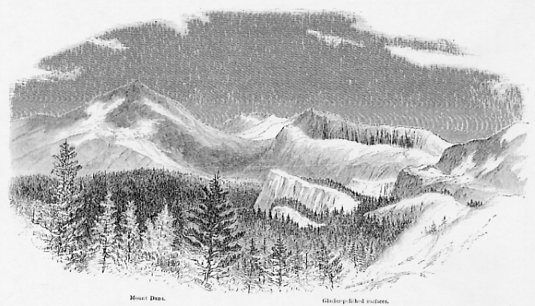

VOLCANIC TABLES ON GRANITE.

[From The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Book > High Sierra >

Next: Chapter 4: The High Sierra (1870) • Index • Previous: Chapter 3: The Yosemite Valley

Having, in the last chapter, given as full a description of the Yosemite Valley as our space will permit, we proceed next to call the reader’s attention to the higher region of the Sierra Nevada, the Alps of California, as the upper portion of this great chain of mountains is sometimes called; this region we designate, for convenience, as the “High Sierra.” It is, however, especially the elevated valleys and mountains which lie above and near the Yosemite that we wish to describe, and to endeavor to bring to the reader’s notice, as this is not only a region central and easy of access, but one extremely picturesque, and offering to the lover of high mountain scenery every possible inducement for a visit. By adding a few more days to the time required for a trip to the Yosemite, the tourist may make himself acquainted with a quite different type of scenery from that of countries usually visited by pleasure travellers, and may enjoy the sight of as lofty snow-covered peaks, and as grand panoramic views of mountain and valley, as he can find in Switzerland itself. This region of the High Sierra in California is hardly yet opened to visitors, as far as the providing for them of public accommodations is concerned, for there is not a hotel, nor a permanently inhabited house, anywhere near the crest of the Sierra, between the Silver Mountain road on the north and Walker’s Pass on the south; but such is the mildness of the summer, and so steady is the clearness of the atmosphere in the Californian high mountains, that, with a very limited amount of preparation, one may make the tour outside of the Yosemite almost without any discomforts, and certainly without any danger. In the Sierra Nevada the entire absence of severe storms during the summer and the almost uninterrupted serenity of the sky particularly invite to pleasure travel. The worrying delays and the serious risks of Alpine travel, caused by long continued rains and storms of wind and hail, with their attendant avalanches of snow and rocks, are unknown in the Californian high mountains, and we have camped by the week together, in the constant enjoyment of the finest weather, at elevations which would seem too great for anything but hardship and discomfort.

A comparison of the Swiss and Californian Alpine scenery is not easy, and yet it seems natural to wish to give some idea of the most striking features of the Sierra by referring for comparison, or contrast, to the mountain scenery of Switzerland, which has become the very focus of pleasure travel for the civilized world.* [*There are probably ten times as many persons in California who have travelled for pleasure in Switzerland, as among these most interesting portions of the Sierra.]

The much smaller quantity of snow and ice in the Sierra, as compared with regions of equal elevation in Switzerland, is the most striking feature of difference between the mountains of the two countries. In the Sierra we see almost exactly what would be presented to view in the Alps, if the larger portion of the ice and snow-fields were melted away. The marks of the old glaciers are there; but the glaciers themselves are gone. The polished surfaces of the rocks, the moraines or long trains of detritus and the striae engraved on the walls of the cañon these speak eloquently of such an icy covering once existing here as now clothes the summits of the Alps.

Another feature of the Sierra, as compared with the Alps, is the absence of the Alpen or those grassy slopes, which occur above the line of forest vegetation, between that and the eternal snow, and which have given their names to the mountains themselves. In the place of these we have in the California mountains the forests extending quite up to the snow-line in many places, and everywhere much higher than in the Alps. The forests of the Sierra, and especially at elevations of 5,000 to 7,000 feet, are magnificent, both in the size and beauty of the trees, and far beyond any in the Alps; they constitute one of the most attractive feature of the scenery, and yet they are somewhat monotonous in their uniformity of type and they give a sombre tone to the landscape, as seen from a distance in their dark shades of green. The grassy valleys, along the streams, are extremely beautiful; but occupy only a small area; and, especially, they do not produce a marked effect in the distant views, since they are mostly concealed behind the ranges, to one looking over the country from a high point.

The predominating features then of the High Sierra are sublimity and grandeur, rather than beauty and variety. The scenery perhaps will produce as much impression, at first, as that of the Alps; but will not invite as frequent visits, or as long a delay among its hidden recesses. Its type is different from that of the Swiss mountains, and should be studied by those who wish to see nature in all her variety of mountain gloom and mountain glory. The many in this country who do not have the opportunity of seeing the Alps should not miss the Sierra if it be in their power to visit it.

For a journey around the Yosemite, or in any portion of the High Sierra, mules or horses may be hired at Bear Valley, Mariposa or Coulterville; and the services of some one who will act as guide can be obtained, usually, at either of these places. But there are, as yet, no regular guides for the high mountains, and travel must increase considerably before any such will be found. A good pedestrian will often prefer to walk, and will pack his baggage on a horse or mule. For convenience and enjoyment, the party should consist of several persons. A good supply of blankets and of provisions, with a few simple cooking utensils, an axe, a light tent, substantial woolen clothes and, above all, or, rather, under all, a pair of boots “made on honor,” with the soles filled with nails—these are the principal requisites. The guide will initiate the unpracticed traveller into the mysterious art of “packing” a mule or horse—an accomplishment which can only be acquired by actual practice; but one on the skillful performance of which much of the traveller’s comfort depends. Those who are familiar with woods-life in California can easily find their way about, with the help of the maps contained in this volume.

It will be the principal object of this chapter to describe the region of the High Sierra adjacent to the Yosemite, and this will first be done; after which, we will add a brief description of some other less known portions of the Sierra, in the hope that travellers may be induced to visit them, and, perhaps, to give to the world some of their experience, for the benefit of future tourists. And, for convenience, we will first describe the trip which is most likely to be made by those visiting the Yosemite, namely an excursion around the Valley, on the outside one, which will reveal much that is of great interest, occupying but few days, and which can be made mostly on beaten trails, without the slightest difficulty or danger. We cannot but believe that the time will soon come when hundreds, if not thousands, will every year visit this region and that it will become as well known as the valleys and peaks of the Oberland.

In making the circuit of the Yosemite, as here proposed, the traveller is supposed to start from the Valley itself, leaving it on the north side and following the Mono trail to Soda Springs, camping there and ascending Mount Dana, then returning by the trail from Mono to Mariposa, passing behind Cloud’s Rest and the Half Dome, through the Little Yosemite, across the Illilouette, by the Sentinel Dome, then to Westfall’s and back into the Valley, or to Clark’s Ranch as may be desired, the whole trip occupying about a week.

Leaving the Valley, the traveller ascends to the plateau by the Coulterville trail; but, instead of keeping on the trail back to that place, turns sharp to the right just after passing the Boundary corner, taking the trail formerly considerably used by mule trains between Big Oak Flat and Aurora. This trail was of some importance at the time that the Esmeralda District was in favor with mining speculators; for, although it rises to the elevation of over 10,700 feet above the sea-level, yet, there being an abundance of feed at the various flats and meadows on the route, which, as they were not claimed or fenced in, were free to all, it offered a more eligible route for large trains of mules than those farther north, where all the grass was taken possession of by settlers and where, consequently, feed must be purchased. In 1863, all the meadows on the Silver Mountain road (the next one north of the Sonora Pass road) were claimed; there were several public houses on the route, and a public conveyance over it; but, at that time, there was not a house or a settler on the Mono trail anywhere between Deer Flat, twenty-two miles below the Yosemite and the eastern base of the Sierra, near Mono Lake; nor is there now, so far as we are informed. The traveller, therefore, will not be able to telegraph, in advance of his arrival, for rooms at the sumptuous hotel at the next station; but he will find grassy meadows in which to pasture his animals, scattered along the route at convenient intervals, will have an abundance of ice-cold water, and, drawing on his saddle-bags for his own rations, with unlimited command of free fuel, he will find both novelty and delight in his entire independence of hotel bills, and in knowing that he is not in danger of being crowded out of his “accommodations.”

The first good camping-ground, after leaving the Valley on the Mono trail, is in the neighborhood of the Virgin’s Tears Creek, and from here the highest of the Three Brothers may be easily reached, in a hour or two. There is no trail blazed as yet; but the shortest and best way can easily be found, in the absence of a guide, by the aid of the map. From this commanding point, almost 4,000 feet above the Valley, the view is extremely fine, the Merced river and green meadows which border it seeming to be directly under the observer’s feet. Probably there is no better place from which to get a bird’s-eye view of the Yosemite Valley itself; and, in respect to the distant views of the Sierra to be had from the summit of the Three Brothers, it can only be said, that, like all the others which can be obtained from commanding positions around the Valley, it seems, while one is enjoying it, to be the finest possible. At the time of our visit to this region in 1866, we climbed a commanding ridge just north of our camp on the Virgin’s Tears Creek, from which a noble panoramic view of the Sierra was had. It was just at sunset, and the effect of color which was produced by some peculiar condition of the atmosphere, and which continued for at least a quarter of an hour, was something entirely unique and indescribably beautiful. The whole landscape, even the foreground and middle ground as well as the distant ranges, beam of a bright Venetian-red color, producing an effect which a painter would vainly attempt to imitate by any color or combination of colors. It was unlike the “Alpine glow,” so often seen in high mountains; for, instead of being confined to the distant and lofty ranges, it tinged even the nearest objects, and not with shades of rose-color and purple but with a uniform tint of brilliant, clear red.

After crossing the Virgin’s Tears, the next creek is that which forms the Yosemite Falls, and which is about two miles farther on. The trail crosses this creek a little above a small meadow, where one can camp, and from which the brink of the fall and the summit of the cliff overhanging it on the east may be visited. A couple of miles farther on is a high meadow called Deer Park, on which there was some snow even in the latter part of June, 1863; for we are here nearly 8,500 feet above the sea-level. Descending a little, we soon reach Porcupine Flat, a small meadow of carices, 8,173 feet above tide-water, and a good camping-ground for those who wish to visit Mount Hoffmann.

This mountain is the culminating point of a group of elevations, very conspicuous from various points about the Yosemite, and especially from the Mariposa trail and from Sentinel Dome, looking directly across the Valley and to the north of it. It is about four miles northwest of Porcupine Flat, and can be reached and ascended without the slightest difficulty. The ridge to which it belongs forms the divide between the head-waters of Tenaya and Yosemite Creeks; the latter heads in several small lakes which lie immediately under the bold mural face of the range, which is turned to the northwest. The summit is 10,872 feet above the sea-level and is a bare granitic mass, with a gently curving slope on the south side, but falling off in a grand precipice to the north, as seen in photograph No. 25, which represents the upper portion of this mountain. This photograph shows also admirably the peculiar concentric structure of the granite of this region of the Sierra, and illustrates some other facts connected with the form and structure of the mountain masses which will be alluded to farther on.

Fig. 9.

VOLCANIC TABLES ON GRANITE. [From The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] |

The view from the summit of Mount Hoffmann is remarkably fine, and those who have not time, or inclination, to visit the higher peaks of the main ridge of the Sierra are strongly advised to ascend this, as the trip from the Yosemite and back need only occupy two or three days; and no one who has not climbed some high point above the Valley can consider himself as having made more than a distant acquaintance with the High Sierra. This is a particularly good point for getting an idea of the almost inaccessible region of volcanic masses lying between the Tuolumne River and the Sonora Pass road. The number of distinct peaks, ridges and tables visible in that direction, crowded together, is too great to be counted. The grand mass of Castle Peak is a prominent and most remarkably picturesque object. This mountain was thus named by Mr. G. H. Goddard, about ten years ago, at which time he ascended, by estimate, to within 1,000 feet of the summit, and calculated it to be 13,000 feet in elevation above the sea-level.* [*Mr. Goddard’s measurement was made with an aneroid barometer, and subsequent examinations along his route, by the Geological Survey, indicate that his figures are about 500 feet too great. Castle Peak is probably between 12,000 and 12,500 feet high. [In the 1871 edition, these numbers were changed to: “... 1,500 feet too great. Castle Peak is probably between 11,000 and 12,000 feet high."]] Messrs. King and Gardner made several attempts to climb Castle Peak; but did not succeed in getting to the top, although Mr. Goddard thinks it can easily be reached from the north. By some unaccountable mistake, the name of Castle Peak was afterwards transferred to a rounded and not at all castellated mass about seven miles north of Mount Dana; but we have returned the name to the peak to which it belongs, and given that of General Warren, the well-known topographer and engineer, to the one on which the entirely unsuitable name of Castle Peak had become fixed. [In the 1871 edition, Whitney refers to Mr. Goddard’s Castle Peak as “Tower Peak” and adds that the name Castle Peak “is now impossible to transfer it back to its rightful ownership. There is also a “Castle Peak” a little north of the Central Pacific Railroad, near Summit Station. In order to avoid confusion and duplication of names, we have given the name of Tower Peak to Goddard’s Castle Peak, and that of Mount Stanford to the Castle Peak in Sierra County.” Today, no peak in the Sierra Nevada is known as “Castle Peak."]

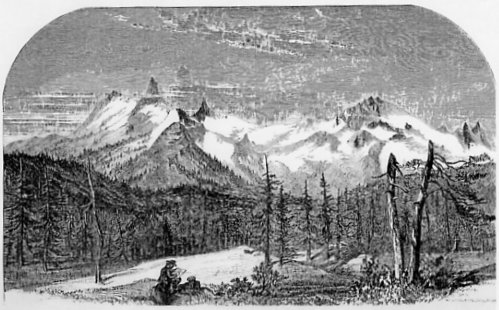

PLATE. IV.

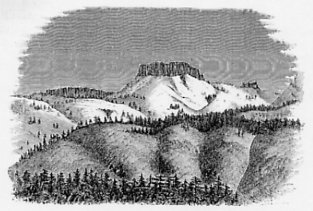

THE OBELISK GROUP—FROM PORCUPINE FLAT. [From The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] |

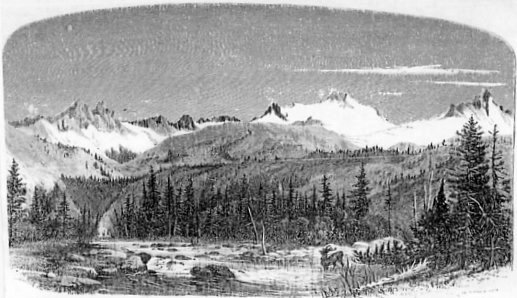

From Porcupine Flat and Mount Hoffmann, we look directly south on to the fine group of mountains lying southeast of the Yosemite and called by us the Obelisk Group, which will be fully described farther on in this chapter. It is a conspicuous feature in the scenery of the region about the Yosemite.

PLATE. V.

UPPER TUOLUMNE VALLEY—FROM SODA SPRINGS, LOOKING SOUTH. [From The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] |

Lake Tenaya, the head of the branch of the Merced of the same name, is the next point of interest on the trail, and is about six miles east-northeast of Porcupine Flat. It is a beautiful sheet of water a mile long and half a mile wide. Photograph No. 26 was taken at the lower end of the Lake, looking northeast towards its head. The trail passes around its east side, and good camping-ground can be found at the upper end in a fine grove of firs and pines. The rocks in the vicinity all exhibit the concentric structure peculiar to the granite of this region, as will be recognized on the photograph. At the head of the Lake is a very conspicuous conical knob of smooth granite, about 800 feet high, entirely bare of vegetation (see photograph), and beautifully scored and polished by former glaciers. The traces of the existence of an immense flow of ice down the valley now occupied by Lake Tenaya begin here to be very conspicuous. The ridges on each side of the trail are worn and polished by glacial action nearly to their summit, so that travelling really becomes difficult for the animals on the pass from the valley of the Tenaya into that of the Tuolumne, so highly polished and slippery are the broad areas of granite over which they have to pick their way. A branch of the great Tuolumne glacier flowed over into the Tenaya Valley through this pass, showing that the thickness of the mass of ice was much more than 500 feet, which is the difference of level between the summit of the pass and the Tuolumne river. As the glacial markings are seen on the rocks around Lake Tenaya at an elevation of fully 500 feet above its level, it is certain that the whole thickness of the ice in the Tuolumne Valley must have been at least 1,000 feet. The summit of the pass is 9,070 feet above the sea-level.

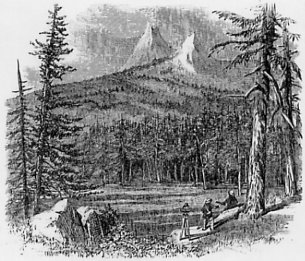

Fig. 10.

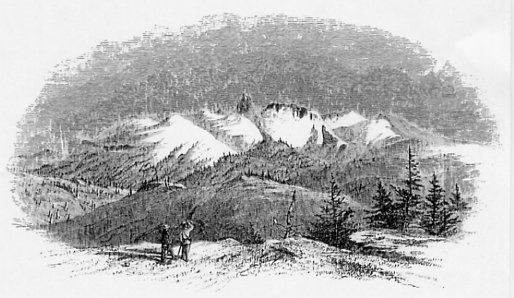

CATHEDRAL PEAK, FROM NEAR LAKE TENAYA. [From The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] |

The trail descends into the valley of the Tuolumne, winding down under the brow of the Cathedral Peak group, a superb mass of rock, which first becomes conspicuously visible to the traveller just before reaching Lake Tenaya. This is one of the grandest land-marks in the whole region, and has been most appropriately named. As seen from the west and southwest, it presents the appearance of a lofty mass of rock, cut squarely down on all sides for more than a thousand feet, and having at its southern end a beautiful cluster of slender pinnacles, which rise several hundred feet above the main body. It requires no effort of the imagination to see the resemblance of the whole to a Gothic cathedral; but the majesty of its form and its vast dimensions are such, that any work of human hands would sink into insignificance beside it. Its summit is at least 2,500 feet above the surrounding plateau, and about 11,000 feet above the sea-level. From the Tuolumne River Valley, on the east, the Cathedral Peak presents a most attractive appearance; but has quite lost the peculiar resemblance which was so conspicuous on the other side. (See photograph No. 27.)

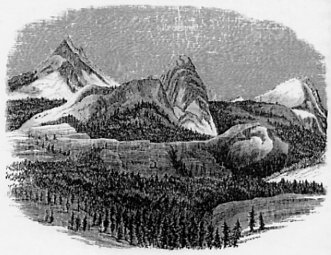

PLATE. VI.

CATHEDRAL PEAK GROUP—UPPER TUOLUMNE VALLEY. [From The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] |

Fig. 11.

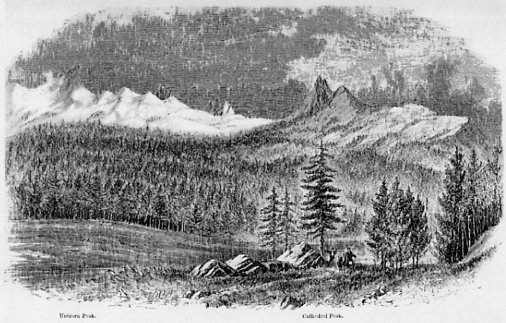

CATHEDRAL PEAK, FROM TUOLUMNE VALLEY. [From The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] |

The valley of the Tuolumne, into which the Mono trail now descends (see map) is one of the most picturesque and delightful in the High Sierra. Situated at an elevation of between 8,000 and 9,000 feet above the sea-level, surrounded by noble ranges and fantastically shaped peaks, rising from 3,000 to 4,000 feet higher, and from which the snow never entirely disappears, traversed by a clear rapid river along which meadows of carices and clumps of pines and firs alternate—the effect of the whole is indeed most superb. The main portion of the valley is about four miles long, and from half to a third of a mile wide. At its upper end it forks, the Mono trail taking the left hand branch, or that which comes down from Mount Dana, while the left hand fork, or that which enters from the southeast, is the one heading on the north side of Mount Lyell (see map), about eight miles above the junction of the two branches. Soda Springs, on the north side of the Tuolumne, near the place where the Mono trail descends into the valley, offers an agreeable camping-ground, and many other pleasant spots can be found between this and the head of the pass. The springs furnish a mild chalybeate water, slightly impregnated with carbonic acid gas, and rather pleasant to the taste. They are elevated thirty or forty feet above the river, and are 8,680 feet above the sea. From this point the view in all directions is a magnificent one. The Cathedral Peak Group (see photograph No. 27), is one of the most conspicuous features in the landscape, the graceful, slender form of the dominating peak being always attractive, from which ever side it is seen. What resembled the spires of a cathedral, in the distant view from the west, near Lake Tenaya, is now seen to be two bare pyramidal peaks rising precipitously from the forest-clothed sides of the ridge to the height of about 2,300 feet above the valley. Farther east the range is continued in a line of jagged peaks and pinnacles, too steep for the snow to remain upon them, and rising above great slopes of bare granite, over which, through the whole summer, large patches of snow are distributed, in sheltered places and on the north side. One of these peaks has a very peculiar horn-shaped outline, and hence was called Unicorn Peak. This range trends off to the southeast and unites with the grand mass of the Mount Lyell group, which forms the dominating portion of the Sierra in this region.

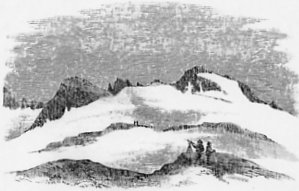

Fig. 12.

GLACIER-POLISHED ROCKS, UPPER TUOLUMNE VALLEY. [From The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] |

The vicinity of Soda Springs and, indeed, the whole region about the head of the Upper Tuolumne is one of the finest in the State for studying the traces of the ancient glacier system of the Sierra Nevada. The valleys of both the Mount Lyell and the Mount Dana forks exhibit abundant evidence of having, at no very remote period, been filled with an immense body of moving ice, which has everywhere rounded and polished the surface of the rocks, up to at least a thousand feet above the level of the river. This polish extends over a vast area, and is so perfect that the surface is often seen from a distance to glitter with the light reflected from it, as from a mirror. Not only have we these evidences of the former existence of glaciers, but all the phenomena of the moraines—lateral, medial and terminal—are here displayed on the grandest scale.

PLATE. VII.

CREST OF THE SIERRA, LOOKING EAST FROM ABOVE SODA SPRINGS. [From The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] |

To the northeast of Soda Springs, a plateau stretches along the southwestern side of the crest of the Sierra, with a gentle inclination towards the river, rising gradually up to a rugged mass of peaks of which Mount Conness is the highest. The plateau lies at an elevation of between 9,000 and 10,000 feet; it has clumps of Pinus contorta scattered over it, and is furrowed by water-courses, which are not very large. The whole surface of this is most beautifully polished and grooved, except where covered with the piles of debris, which stretch across it in long parallel lines, and which are the medial moraines of the several side glaciers, which formerly united with the main one, coming down from the gorges and cañons of the great mass of the Sierra above. About a mile below the Springs are the remains of a terminal moraine, stretching across the valley; it is not very conspicuous, except from the fact that it bears a scattered growth of pines, contrasting beautifully with the grassy and level area above and below. A mile and a half lower down, a belt of granite, a mile or more wide, extends across the valley; over this the river falls in a series of cascades, having a perpendicular descent of above a hundred feet in all. This granite belt is worn into many knobs, some of which are a hundred feet high and over; between these, are great grooves and channels, worn by ice, and their whole surface, to the very summit, is scratched and polished, the markings being parallel with the present course of the river.

Below this is another grassy field, and then the river enters a cañon, which is about twenty miles long, and probably inaccessible through its entire length; at least we have never heard of its being explored, and it certainly cannot be entered from its head. Mr. King followed the cañon down as far as he could, to where the river precipitated itself down in a grand fall, over a mass of rock so rounded on the edge, that it was impossible to approach near enough to look over into the chasm below, the walls on each side being too steep to be climbed. Where the cañon opens out again, twenty miles below, so as to be accessible, a remarkable counterpart of the Yosemite Valley is found, called the Hetch-Hetchy Valley, which will be described farther on. Between this and Soda Springs there is a descent in the river of 4,500 feet, and what grand waterfalls and stupendous scenery there may be here it is not easy to say. Although we have not succeeded in getting into this cañon, it does not follow that it cannot be done. Adventurous climbers, desirous of signalizing themselves by new discoveries, should try to penetrate into this unknown gorge, which may perhaps admit of being entered through some of the side cañons coming in from the north, and which must exhibit stupendous scenery. The region north of this cañon, as far as the Sonora road across the Sierra, is wonderfully wild and difficult of access. Our parties made some attempt to penetrate it, and to reach Castle Peak, but without success, partly owing to the great difficulty of finding feed for the animals.

Just before reaching the head of the great cañon, there is an isolated granite knob in the valley, rising to the height of about 800 feet above the river, and beautifully glacier-polished to its very summit. At this point, the great glacier of the Tuolumne must have been at least a mile and a half wide and over 1,000 feet thick. From this knob the view of the valley and the surrounding mountains is one hardly surpassed in interest and grandeur. In the lower part of the valley are the smooth and glittering surfaces of granite, indicating the former existence of the glacier; above this, on either hand, the steep slopes of the mountains, clad with a sombre growth of pines (Pinus contorta) , and beyond, still higher up, the great snow-fields, above which rise the Unicorn and many nameless pinnacles or peaks, in grand contrast with the dome-shaped masses seen, in the farthest distance, in the direction of Lake Tenaya.

Of all the excursions which can be made from Soda Springs, the one most to be recommended is the ascent of Mount Dana, as being entirely without difficulty or danger, and as offering one of the grandest panoramic views which can be had in the Sierra Nevada; those who wish to try a more difficult feat can climb Mount Lyell or Mount Conness.* [*Mount Dana was named after Professor J. D. Dana, the eminent American geologist; Mount Lyell from Sir Charles Lyell, whose admirable geological works have been well known to students of this branch of science, in this country, for the past thirty years. Mount Conness bears the name of a distinguished citizen of California, now a U. S. Senator, who deserves, more than any other person, the credit of carrying the bill organizing the Geological Survey of California through the Legislature, and who is chiefly to be credited for another great scientific work, the Survey of the 40th Parallel.] Since the visit of the Geological Survey to this region, in 1863, several parties have ascended Mount Dana, riding nearly to the summit on horseback, and there can be no doubt that the ascent will, in time, become well-known, and popular among tourists. As it is rather too hard a day’s work to go from Soda Springs to the summit of Mount Dana and back in a day, it will be convenient to move camp to the base of the mountain, near the head of the Mono Pass. The distance from the springs to the summit of the pass is about ten miles in a straight line, and perhaps twelve in following the trail. A convenient place for camping, and from which to ascend Mount Dana, is at a point about three miles from the summit of the pass, on the left bank of the stream and near the junction of a small branch, coming in from the slopes of Mount Dana to unite with the main river, which heads in the pass itself and along the ridges to the southeast of it. This camp is 9,805 feet above the sea and about a thousand feet below the summit of the pass, which is 10,765 feet in elevation.

An examination of the map will give a better idea than any verbal explanation can do, of the character and position of the subordinate members of the crest of the Sierra in this region. A jagged line of granite pinnacles runs from the head of the San Joaquin river northwest, for about twenty miles, beginning at the Minarets and ending at Cathedral Peak. Mount Ritter, Mount Lyell and Mount Maclure are the only points in this range that we have named;† [†Ritter is the name of the great German geographer—the founder of the science of modern comparative geography. To the pioneer of American geology, William Maclure, one of the dominating peaks of the Sierra Nevada is very properly dedicated.] they are all about 13,000 feet high.

PLATE. VIII.

MOUNT LYELL GROUP, AND THE SOURCE OF THE TUOLUMNE RIVER. [From The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] |

From Mount Lyell starts off a grand spur connecting with the Obelisk Group range, which runs parallel with the Mount Lyell range and about ten miles from it. About the same distance from the latter, in the opposite direction from the Obelisk Group, is another serrated line of peaks of which Mount Conness is the culminating point. Connecting the Mount Lyell and the Mount Conness ranges, and forming the main divide of the Sierra, in this part, is a series of elevations which have rounded summits and rather gently-sloping sides, contrasting in the most marked manner with the pinnacles and obelisks of the other ranges. This portion of the Sierra runs north and south, and has as its dominating mass Mount Dana, which appears to be the highest point anywhere in this region, and which was, for a considerable time, supposed by us to be the highest of the whole Sierra, with the exception of Mount Shasta. Mount Dana and Mount Lyell are so nearly of the same height that the difference falls within the limits of possible instrumental error; but on levelling, with a pocket-level, from one to the other, the former seemed to be a little the higher of the two.

Mount Dana is the second peak north of the pass; the one between that mountain and the pass is called Mount Gibbs. Between the two is a gap somewhat lower than the Mono Pass, but descending too steeply on the eastern side to admit of use without considerable excavation. There is also another pass on the north side of Mount Dana, as represented on the map; this is about 600 feet lower than the Mono Pass, and might probably be made available with a small expenditure. From the summit everywhere to the east, the descent is exceedingly rapid; that through “Bloody Cañon,” as the east slope of the Mono Pass is called, lets the traveller down 4,000 feet in three miles. The total descent from the summit of Mount Dana to Mono Lake is 6,773 feet and the horizontal distance only six miles, or over 1,100 feet fall to the mile.

We ascended Mount Dana twice from the south side without difficulty, sliding down on the snow for a considerable portion of the way, on the return, making a descent of about 1,200 feet in a couple of minutes. We have been told, however, that the approach to the summit from the opposite side is much easier, and that it is even possible to ride a horse nearly to the top from the northwest. The height was determined by us to be 13,227 feet, and it need hardly be added that the view from the summit is sublime. Every tourist who wishes to make himself acquainted with the high mountain scenery of California should climb Mount Dana; those who ascend no higher than the Yosemite, and never penetrate into the heart of the mountains, should never undertake to talk of having seen the Sierra Nevada;—as well claim an intimate acquaintance with the Bernese Oberland, after having spent a day or two in Berne, or with Mont Blanc, after visiting Geneva. The Yosemite is something by itself; it is not the High Sierra; it belongs to an entirely different type of scenery. From Mount Dana, the innumerable peaks and ranges of the Sierra itself, stretching off to the north and south, form, of course, the great feature of the view. To the east, Mono Lake lies spread out, as on a map, at a depth of nearly 7,000 feet below, while beyond it rise, chain above chain, the lofty and, here and there, snow-clad ranges of the Great Basin—a region which may well be called a wilderness of mountains, barren and desolate in the highest degree, but possessing many of the elements of the sublime, especially vast extent and wonderful variety and grouping of mountain forms.

The upper part of Mount Dana is not granite, as are almost all the surrounding peaks. It is made up of slate, very metamorphic near the summit and showing, farther down, especially on the south side, alternating bands of bright green and deep reddish-brown, and producing a very pleasing effect, by the contrast of these brilliant colors, especially when the surface is wet. This belt of metamorphic rock is seen to extend for a great distance to the north, giving a rounded outline to the summits in that direction, of which Mount Warren, about six miles distant and 13,000 feet high, as near as we could estimate, is one of the most prominent.

Along the western and southern slopes of Mount Dana the traces of ancient glaciers are very distinct, up to a height of 12,000 feet. In the gap directly south of the summit a mass of ice must once have existed, having a thickness of at least 800 feet, at as high an elevation as 10,500 feet. From all the gaps and valleys of the west side of the range, tributary glaciers came down, and all united in one grand mass lower in the valley, where the medial moraines which accumulated between them are perfectly distinguishable, and in places as regularly formed as any to be seen in the Alps at the present day. On the eastern side of the pass, also, the traces of former glacial action are very marked, from the summit down to the foot of the cañon; and there are several small lakes which are of the kind known as “moraine lakes,” formed by the damming up of the gorge by the terminal moraines left by the glacier as it melted away and retreated up the cañon.

Of the high peaks adjacent to Mount Dana, Mount Warren was ascended by Mr. Wackenreuder, and Mount Conness by Messrs. King and Gardner. The latter was reached by following a moraine which forms, as Mr. King remarks, a good graded road all the way round from Soda Springs to the very foot of the mountain. The ascent was difficult and somewhat hazardous, the approach to the summit being over a knife-blade ridge, which might be trying to the nerves of the uninitiated in mountain climbing. The summit is 12,692 feet above the sea-level, and is of granite, forming great concentric plates dipping to the west. Of course, the view, like all from the dominant peaks of this region, is extensive, and grand beyond all description.

Fig. 13.

SUMMIT OF MOUNT LYELL. [From The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] |

Our party also ascended the Mount Lyell fork, following up the Valley represented in photograph No. 28, which will give a good idea of this elevated region of the Sierra. The highest point of the group was ascended by Messrs. Brewer and Hoffmann; but they were unable to reach the very summit, which was found to be a sharp and inaccessible pinnacle of granite rising above a field of snow. By observations taken at a station estimated to be 150 feet below the top of this pinnacle, Mount Lyell was found to be 13,217 feet high. The ascent was difficult, on account of the body of snow which had to be traversed and which was softened by the sun, so that climbing in it was very laborious. This trouble might have been obviated, however, by camping nearer the summit and ascending before the sun had been up long enough to soften the snow. The culminating peaks of Mount Lyell have a gradual slope to the northeast; but, to the south and southwest, they break off in precipices a thousand feet or more in height. Between these cliffs, on that side, a vast amphitheatre is included, once the birth-place of a grand glacier, which flowed down into the cañon of the Merced. From this point, the views of the continuation of the chain to the southeast are magnificent. Hundreds of points, in that direction, rise to an elevation of over 12,000 feet, mostly in jagged pinnacles of granite, towering above extensive snow-fields, with small plateaux between them. This continuation of the range to the southeast of Mount Lyell was afterwards visited by another party, and the peak called on the map Mount Ritter was ascended, as will be noticed farther on, after completing the tour around the Yosemite.

If the traveller has ascended Mount Dana, he will probably desire to return down the Tuolumne Valley and continue his journey on the trail leading south of Cloud’s Rest, to the Little Yosemite and Sentinel Dome, and so back to Clark’s Ranch. This trail strikes directly south from the crossing of the Tuolumne, a little below Soda Springs, and passes close under Cathedral Peak, on the west side, then along the back, or east side of Cloud’s Rest, and down into the Little Yosemite Valley as it is called.

This is a flat valley, or mountain meadow, about four miles long and from half a mile to a mile wide. It is enclosed between walls from 2,000 to 3,000 feet high, with numerous projecting buttresses and angles, topped with dome-shaped masses. At the upper end of the Valley it contracts to a V-shaped gorge, through which the Merced rushes with rapid descent, over huge masses of debris. The Little Yosemite Valley is a little over 6,000 feet above the sea-level, or 2,000 above the Yosemite, of which it is a kind of continuation, being on the same stream—namely, the main Merced—and only a short distance above the Nevada Fall, from the summit of which easy access may be had to it, whenever the bridge across the river between the Vernal and Nevada Falls has been rebuilt. This bridge, which was carried away in the winter of 1867-8, obviated the necessity of a very circuitous and difficult climb, to get from the base of the Nevada Fall to its summit, the ascent being quite easy on the north side of the river. On the south side, about midway up the Valley, a cascade comes sliding down in a clear sheet over a rounded mass of granite; it was estimated at 1,200 feet in height. The concentric structure of the granite is beautifully marked in the Little Yosemite; the curious rounded mass, called the Sugar Loaf, is a good instance of this.

The trail, leaving the Little Yosemite, crosses the divide between the Merced and the Illilouette, then the last-named stream, passing to the west of Mount Starr King, another of those remarkable conical knobs of granite, of which there is quite a group in this vicinity. In photograph No. 15, taken looking up the Illilouette Cañon, the summit of Mount Starr King is just visible in the distance, nearly concealed behind another of these domes or cones, of which the outline can hardly be made out in the photograph. Starr King is the steepest cone in the region, with the exception of the Half Dome, and is exceedingly smooth, having hardly a break in it; the summit is quite inaccessible, and we have not been able to measure its height.

There is nothing more of particular interest in this vicinity, nor before reaching Westfall’s meadows, except the Sentinel Dome. This may be visited from Ostrander’s, from which a trail has been blazed, or from the Illilouette Valley direct, on the return route. Horses may be ridden nearly to its summit, which is a great rounded mass of granite, with a few straggling pines on it. The view it commands is indeed sublime.

Photographs Nos. 19, 20 and 21 were taken from the Sentinel Dome, and are numbered in order from the north around to the east. In No. 19 we have, on the extreme left of the picture, the snow-covered mass of Mount Hoffmann, and, nearly under it, the rounded summit of the North Dome, and another similar mass of granite near it. In the centre of the picture, the view extends directly up the Tenaya Cañon, past the stupendous vertical face of the Half Dome, on to the bare regular slope of Cloud’s Rest, while on the opposite side of the cañon we see Mount Watkins, and, in the distance, the serrated crest of the Sierra. The points next to the left of Cloud’s Rest, and directly over the Tenaya Cañon, belong to the Cathedral Peak and Unicorn Peak ranges, which are such prominent features in the view from Soda Springs. The tip of Cathedral Peak is just seen rising above the intervening ranges. Beyond, in the farthest distance, we have the higher range of Mount Conness and the adjacent peaks. The Half Dome is the great feature in this view, and no one can form any conception of its grandeur, who has only seen it from the Valley below. On the Sentinel Dome we are 4,150 feet above the Valley; but still lack 587 feet of being as high as the summit of the Half Dome.

In No. 2 of the views from Sentinel Dome (see photograph No. 20) the eye is directed, in the centre of the picture, to the Nevada Fall, with the Cap of Liberty on the left of it. Just above the latter we look into the Little Yosemite, and see a spot of its level floor, surrounded by bare shelving granite masses. On the extreme left is a small portion of the bare side of the Half Dome, and the farthest point to the right is the Obelisk, or Mount Clark, the most western and dominating point of the Merced Group, its sides streaked with snow. In the extreme distance is the mass of mountains which we have called the Mount Lyell Group.* [*Mount Lyell and Mount Maclure are two dark points visible to the right and the left of a snow-covered peak, rising in the farthest distance between the Nevada Fall and the Cap of Liberty.]

View No. 3 from the Sentinel Dome (photograph No. 21) gives us the whole of the Merced Group, in the distance, the Obelisk on the left, and the three other principal peaks to the right. In the middle ground of the picture is the curious elevation, called Mount Starr King, mentioned before as being a steep, bare, inaccessible cone of granite, surrounded by several others of the same pattern, but of smaller dimensions.

The Sentinel Dome may easily be reached by the traveller to the Yosemite, by stopping over a day, on the way to or from the Valley, at Westfall’s meadow. It makes just a pleasant day’s excursion to ride to the Dome and back, with a few hours to remain on the summit. But if one is in a hurry, it is possible to make the trip and return in time to reach either Clark’s or the Yosemite before night. To visit this region and not ascend Sentinel Dome is a mistake; only those who have had the pleasure of making this excursion can appreciate how much is lost by not going there.

There is one point overhanging the Valley, about half a mile northeast of the Sentinel Dome, and directly in a line with the edge of the Half Dome. This is called Glacier Point, and from it the view in photograph No. 22 was taken. This combines perhaps more elements of beauty and grandeur than any other single view about the Valley. The Nevada and Vernal Falls are both plainly in sight, and directly over them is the Obelisk, with a portion of the range extending off to the right, until concealed behind the conical mass of Mount Starr King. To the left of the Cap of Liberty is the depression in which lies the Little Yosemite, and beyond this, in the farthest distance, the lofty summits of the Mount Lyell Group. The pines fringing the edge of Glacier Point are the Pinus Jeffreyi. The view of the Half Dome from this point is stupendous, as the spectator is very near to that object, and in a position to see it almost exactly edgewise. We regret that we are not above to give a photograph of it from this point of view. Language is powerless to express the effect which this gigantic mass of rock, so utterly unlike anything else in the world, produces on the mind.

We have thus conducted the traveller around the Valley, and given him as many hints as our space will admit, as to the character and locality of the objects to be seen on the route. A week is surely very little to devote to this excursion; and, when we consider how much can be seen and enjoyed during this time, it seems as if every one would be desirous of taking the opportunity of being at the Yosemite to make this addition to his travelling experience. The time will certainly come when this will be fully recognized, and when the rather indistinct trail around the Valley will be as well beaten, as the one which now leads into it.

For those who desire to extend their knowledge of the High Sierra still farther, there are numerous mountains, peaks, passes and valleys to be visited, each one of which has its own peculiar beauties and attractions.

The Merced Group, which is so conspicuous an object in the view from Sentinel Dome and many other points about the Yosemite, offers a fine field for exploration. This group is a side-range, parallel with the main one, and about twelve miles from it. It runs from a point near the Little Yosemite, for about twelve miles, and then meets the transverse range coming from Mount Lyell and forming the divide between the San Joaquin and the Merced. Intersecting this, the Merced Group is continued to the southeast and runs into a high peak, called Black Mountain; it then falls off, and becomes lost in the plateau which borders the San Joaquin.

At the northeast extremity of the group is the grand peak to which we first gave the name of the “Obelisk,” from its peculiar shape, as seen from the region to the north of the Yosemite. It has, since that, been named Mount Clark, while the range to which it belongs is sometimes called the Obelisk Group; but, oftener, the Merced Group, because the branches of that river head around it. This is a noble range of mountains, with four conspicuous summits and many others of less prominence. The dominating peaks all lie at the intersection of spurs with the main range, as will be seen on the map. Mount Clark, or the Obelisk, is the one nearest the Yosemite. All these peaks are nearly of the same height. The one next south of the Obelisk was called the Gray Peak, the next the Red Mountain, and the next Black Mountain, from the various colors which predominate on their upper portions. The last name had, however, been previously given to the highest point of the mass of ridges and peaks at the southern extremity of the range, south of the divide between the San Joaquin and the Merced. All of these points except Gray Peak have been climbed by the Geological Survey, and they are all between 11,500 and 11,700 feet in elevation. Mount Clark was found to be an extremely sharp crest of granite, and was not climbed without considerable risk. Mr. King, who, with Mr. Gardner, made the ascent of the peak, says that its summit is so slender, that when on top of it they seemed to be suspended in the air.

An examination of the photographs and the map will show how the spurs of the Merced Group break off in bold precipices to the north, with a more gradual descent to the south, a peculiarity already mentioned as existing at the summit of Mount Hoffmann. The same is the case with the long crested ridge which forms the divide between the waters of the Merced and the San Joaquin. All these spurs and ridges open to the north with grand amphitheatres, where great glaciers once headed. The space enclosed between the Merced Group, the Mount Lyell Group and the divide of the San Joaquin and Merced forms a grand plateau, about ten miles square, into which project the various spurs, coming down in parallel order, while in the centre there is a deep trough, sunk 2,000 feet below the general level, in which runs the Merced. The views from all the dominating points on the ridges surrounding this plateau are sublime, the region being one of the wildest and most inaccessible in the Sierra.

Our party, in charge of Mr. King, made an attempt to climb Mount Ritter; but, on account of the unfavorable weather, did not succeed in quite reaching the summit. They approached it from the southwest, passing to the south of Buena Vista Peak and Black Mountain. The Merced divide was found to be everywhere impassable for animals. Mr. King evidently considers Mount Ritter the culminating point of this portion of the Sierra; as he says that he climbed to a point about as high as Mount Dana, and had still above him an inaccessible peak some 400 or 500 feet high. To the south of this are some grand pinnacles of granite, very lofty and apparently inaccessible, to which we gave the name of “the Minarets.” Our space is not sufficient to enable us to go into a description of this region; suffice it to say, that there are here numerous peaks, yet unscaled and unnamed, to which the attention of mountain climbers is invited. Any one of them will furnish a panoramic view which will surely repay the lover of Alpine scenery for the expenditure of time and muscle required for its ascent.

There is a very interesting locality on the Tuolumne river, about sixteen miles from the Yosemite in a straight line, and in a direction a little west of the north. It is called the Hetch-Hetchy Valley, an Indian name, the meaning of which we have been unable to ascertain. It is not only interesting on account of the beauty and grandeur of its scenery; but, also because it is, in many respects, almost an exact counterpart of the Yosemite. It is not on quite as grand a scale as that valley; but, if there were no Yosemite, the Hetch-Hetchy would be fairly entitled to a world-wide fame; and, in spite of the superior attractions of the Yosemite, a visit to its counterpart may be recommended, if it be only to see how curiously nature has repeated herself.

The Hetch-Hetchy may be reached easily from Big Oak Flat, by taking the regular Yosemite trail, by Sprague’s ranch and Big Flume, as far as Mr. Hardin’s fence, between the South and Middle Forks of the Tuolumne river. Here, at a distance of about eighteen miles from Big Oak Flat, the trail turns off to the left, going to Wade’s meadows, or Big Meadows as they are also called, the distance being about seven miles. From Wade’s ranch the trail crosses the middle fork of the Tuolumne, and goes to the “Hog ranch,” a distance of five miles, then up the divide between the middle fork and the main river, to another little ranch, called “the Cañon.” From here, it winds down among the rocks, for six miles, to the Hetch-Hetchy, or the Tuolumne Cañon. This trail was made by Mr. Joseph Screech, and is well blazed and has been used for driving sheep and cattle into the Valley. The whole distance from Big Oak Flat is called thirty-eight miles. Mr. Screech first visited this place in 1850, at which time the Indians had possession. The Pah Utes still visit it every year for the purpose of getting the acorns, having driven out the western slope Indians, just as they did from the Yosemite.

The Hetch-Hetchy is between 3,800 and 3,900 feet above the sea-level, or nearly the same as the Yosemite; it is three miles long east and west; but is divided into two parts by a spur of granite, which nearly closes it up in the centre. The portion of the Valley below this spur is a large open meadow, a mile in length and from an eighth to half a mile in width, with excellent grass, timbered only along the edge. The meadow terminates below in an extremely narrow cañon, through which the river has not sufficient room to flow at the time of the spring freshets, so that the Valley is then inundated, giving rise to a fine lake. The upper part of the Valley, east of the spur, is a mile and three quarters long, and from an eighth to a third of a mile wide, well timbered and grassed. The walls of this Valley are not quite as high as those of the Yosemite; but, still, anywhere else than in California, they would be considered as wonderfully grand. On the north side of the Hetch-Hetchy is a perpendicular bluff, the edge of which is 1,800 feet above the Valley, and having a remarkable resemblance to El Capitan. In the spring, when the snows are melting, a large stream is precipitated over this cliff, falling at least 1,000 feet perpendicular. The volume of water is very large, and the whole of the lower part of the Valley is said to be filled with its spray.

A little farther east is the Hetch-Hetchy Fall, the counterpart of the Yosemite. The height is 1,700 feet. It is not quite perpendicular; but it comes down in a series of beautiful cascades, over a steeply inclined face of rock. The volume of water is much larger than that of the Yosemite Fall, and, in the spring, its noise can be heard for miles. The position of this fall in relation to the Valley is exactly like that of the Yosemite Fall, in its Valley, and opposite to it is a rock much resembling the Cathedral Rock, and 2,270 feet high.

At the upper end of the valley the river forks, one branch, nearly as large as the main river, coming in from near Castle Peak. Above this, the cañon, so far as we know, is unexplored; but, in all probability, has concealed in it some grand falls. There is no doubt that the great glacier, which, as already mentioned, originated near Mount Dana and Mount Lyell, found its way down the Tuolumne Cañon, and passed through the Hetch-Hetchy Valley. How far beyond this it reached, we are unable to say, for we have made no explorations in the cañon below. Within the Valley, the rocks are beautifully polished, up to at least 800 feet above the river. Indeed, it is probable that the glacier was much thicker than this, for, along the trail, near the south end of the Hetch-Hetchy, a moraine was observed at the elevation of fully 1,200 feet above the bottom of the Valley. The great size and elevation of the amphitheatre in which the Tuolumne glacier headed caused such an immense mass of ice to be formed, that it descended far below the line of perpetual snow before it melted away. The plateau, or amphitheatre, at the head of the Merced was not high enough to allow a glacier to be formed of sufficient thickness to descend down as far as into the Yosemite Valley; at least, we have obtained no positive evidence that such was the case. The statement to that effect in the “Geology of California,” vol. I., is an error; although it is certain that the masses of ice approached very near to the edge of the Valley, and were very thick in the cañon to the southeast of Cloud’s Rest, and on down into the Little Yosemite.

Next: Chapter 4: The High Sierra (1870) • Index • Previous: Chapter 3: The Yosemite Valley

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/the_yosemite_book/chapter_4.html