| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Cabin Homes >

Next: Chapter 12 • Index • Previous: Chapter 10

|

You must come home with me and be my guest;

You wilt give joy to me, and I will do All that is in my power to honor you.

—Shelley’s

Hymn to Mercury.

|

|

No little room so warm and bright,

Wherein to read, wherein to write.

—Tennyson.

|

|

The glorious Angel, who was keeping

The gates of light, beheld her weeping; And, as he nearer drew and listen’d To her sad song, a tear-drop glisten’d Within his eyelids, like the spray From Eden’s fountain, where it lies On the blue flow’r, which—Bramins say— Blooms nowhere but in Paradise.

—Moore’s Lalla Rookh—Paradise and the Peri.

|

There are probably not many persons, even when philosophically predisposed, who can fully comprehend the possibility of comfort and contentment in such an isolated locality as Yo Semite, for a home in winter as well as in summer, unless in unison with the sentiments of Euripides, that,

“Not mine

This saying, but the sentence of the sage

‘Nothing is stronger than necessity.’”

But if to this be added a suggestive stanza from Mary Howitt:

“In the poor man’s garden grow,

Far more than herbs and flowers,

Kind thoughts, contentment, peace of mind,

And joy for weary hours,”

There may be disclosed the soothing sedative of resignation to tolerate and endure it. Still, to the many, every moment of such a life would bring its burden of irksomeness, and perhaps of

|

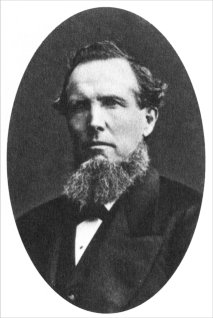

| JAMES C. LAMON. |

After satisfactory demonstration that a residence at Yo Semite in winter was possible, as narrated in a After the experiences narrated in the preceding chapter, Mr. Jas. C. Lamon, who formed one of our setting-out party on that occasion, was the first to try the experiment, and spent the winters of 1862-63 and 1863-64 there entirely alone. As Mr. Lamon was long and favorably known by visitors, not only for his uniform kindness and many manly virtues, but as one of the early settlers in Yo Semite, I feel that this work would be incomplete without his portrait and a brief biographical outline.

Mr. James C. Lamon was born in the State of Virginia in 1817. In 1835 he emigrated to Illinois; and from there to Texas, in 1839. In 1851 he arrived in California, and located in Mariposa County, where, in connection with David Clark, he engaged in the saw-mill and lumber business, until 1858. In June, 1859, he arrived in Yo Semite, and assisted in building the upper hotel, since known as the Hutchings House. In the fall of that year he located a pre-emption claim at the upper end of the valley; cultivated it for garden purposes, planted a fine orchard, and built

|

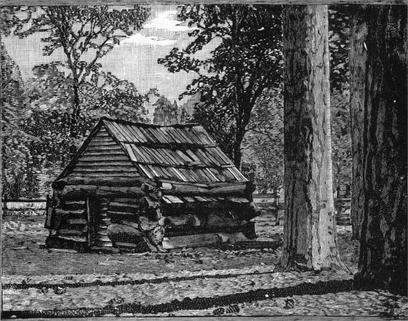

| THE LAMON CABIN. |

By his indomitable will, assisted by his general intelligence and unflagging industry, to which were united habits of temperance and frugality, and the denial to himself of many com forts, he caused the spot known as Lamon’s Garden, once a wilderness, “to blossom as the rose,” and “Lamon’s Berry Patch” and orchard, to become synonymous with enjoyment; the memory of a visit to which was pleasurably treasured by tourists, throughout the civilized world.

As the lofty mountains surrounding his cabin and garden threw long and chilling shadow-frowns upon him during winter, he erected a small house on the sunny side of the valley; and, as a precaution against Indian treachery, lived in its basement. This, however, being flooded during a heavy and continuous rain, he afterwards built a commodious log-cabin, that, upon emergency, might be to him both a fortress and a home. The land around it he fenced and cultivated; and it now—under the vigilant care of Mr. A. Harris—presents a picture of pastoral loveliness which is in striking contrast to that outside of it.

Notwithstanding these valuable and attractive additions to the enjoyments of the valley, the Board of Yo Semite Commissioners declined in every way to recognize his rights as a bona fide settler, and he—with the writer—was notified that he must take a lease of all his premises from them, on or before a given time, or leave. As neither of us would accept either of these alternatives, there ensued the conflict briefly outlined in the succeeding chapter, which resulted, finally, in the State’s recognizing at least the equities of our claims, and the payment to Mr. Lamon, in 1874, of $12,000 as compensation therefor.

This modest sum, the fruits of fifteen years’ laborious toil, although so much calculated to smooth the pathway of his declining years, by lifting him above financial care, was, in its enjoyment, of very brief duration; for, just as he had begun to realize the full fruition of its blessedness, death came with

“That golden key

That opes the palace of eternity,”

May 22, 1875, at the age of 58 years. His remains are interred in the Yo Semite Cemetery, near Yo Semite Falls, amid the scenes of grandeur he loved so well; and here a monolith of Yo Semite granite marks the spot where he rests.

Incidental mention is above made of Mr. Lamon’s residence in the Yo Semite Valley two winters alone, without a neighbor, or even a friendly dog, to keep him company.* [* He was never married.] Supplemental to this there is a sequel that deserves a kindly record: While thus passing his lonely existence there, an Indian had been seen in the settlements with a fine gold watch, that, it was surmised, belonged to Mr. Lamon. Fearing that its supposed owner had been murdered, as well as robbed, three friends left Mariposa—one of whom was Mr. Galen Clark, for many years the guardian of the valley, and still a much respected resident there—for the purpose of ascertaining the facts of the case. Upon arrival, to their great joy, they found the man, presumably murdered, busily engaged in preparing his evening meal. Both Mr. Lamon and his watch were proven to be safe. It can readily be conjectured that their congratulations and rejoicings must have been mutual, although viewed from widely different standpoints.

“Of all the homes that I have seen, in all my travels, this is the most delectable.”

—Canon Kingsley.

As the sun did not rise upon the hotel until half past one in the afternoon, and set again, there, at half past three; so small a modicum of sunlight caused us to look out from the depressing and frosty shadows of our mountainous surroundings, to the brightness of the opposite side; and created within us a longing for the sunlight that was there bathing every tree and mountain with cheerfulness and joy. “Ah!” we would all spontaneously ejaculate, “that is the place to live, in winter.” Even the poultry, that huddled together in a corner shiveringly, would look at us with seeming remonstrance, as though they would admonish us to remove them over there.

| |

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| Hutchings’ Old Log Cabin. Yo Semite. | |

“Besides,” the ladies would exclaim, “how beautifully picturesque a log-cabin would look over yonder in the sunlight, with a dark rich setting of oaks around it; to say nothing of the pleasure of listening to the grandest of perpetual anthems from the Yo Semite Fall, just at its back; or of the homelike comfort there would be within and around it.”

A site possessing the qualities deemed most desirable was accordingly selected, and a “log-cabin,” in all its symmetrical proportions and artistical surroundings, began to stand out upon the landscape. How cheerily anxious did the gentler sex watch the placing of each and every log, and sometimes assisted in putting them in position. By degrees, and with the assistance of our neighbor, Mr. Lamon, and his cattle, it was finished. One rock formed the mantel, and another the hearth-stone, of our broad and cheery open fire-place. Our greatest trouble was with the chimney—it would smoke. Everybody, “including his wife,” is familiar with the adage that “a smoking chimney, and scolding ——, etc. [we had not the latter], are among the greatest trials of life.” Finally, by means of books (for we had no practical knowledge) we learned that “a chimney, to draw well, should never be less than twice the size of the throat, from the latter to the top, which should always be above the house.” This principle, when applied to ours, made it an eminent success. And this item is here introduced for the benefit of those having that dire infliction—a smoky chimney.

The cabin, therefore, with all its comfort-aiding appointments, became a delightful reality, and soon sheltered a happy and contented family, though entirely isolated from the great throbbing heart of the world outside. On bright days we enjoyed the blessed sunshine from nine in the morning until half-past three in the afternoon—a gratifying contrast to the other side—and, when the storm swooped down upon us, we listened thank fully to the music of the rain upon the roof, and to the wind among the tree-tops, or the rushing avalanches down the mountain-sides; or watched the crystal forms of the fast-falling snow upon, or from, our windows; or our busy little snow-bird guests eating their daily meal of crumbs from off the window-sill.

It must not, however, be supposed that our daily life here was like that pictured by some dreamy Christians of the life hereafter—” sitting, placidly, on a cloud, and blowing a silver trumpet.” Far from it. Every day brought its duties, in fair weather or in foul. Here, too, we learned a secret, and one worth revealing, as it is one in which the daily happiness of all largely consists—it is that of having constant and pleasant occupation, for both body and mind. This will count better in results, and go farther, than any number of gilded theories, for this life or the next. There are always to be found some kindly services to be rendered, or duties to be performed, not only in the family circle, but in the teeming world around us, if we do not allow ourselves to shirk them. And, believe me, the noble and conscientious performance of a generous act, brings with it a full and generous reward, without waiting for that expected in the hereafter. To those who have both leisure and means—and they must be poor indeed who have not some—I would say, “Know you not some poor child, or woman, or man, to whom you can carry some blessing, if only that of help and sympathy?” By so doing, you not only assist to make up their heaven, and an earthly one for yourselves, but, in my judgment, much better please the loving God, whom you profess to serve. If there should ever come a new religion, it will be founded upon humanity, as being more nearly akin to the beneficent and ennobling plan of the Infinite One. Think of this.

Returning from this diversion, if you could have taken a glimpse on the inside of our cabin on a winter’s night, you would have seen not only a bright log fire, and clean hearth-stone, but a little circle of bright faces; almost aglow with watching the phantom forms that might come and go among the scintillations of the blazing heat; or, with busy thoughts were weaving gossamer plans of future happiness; while nimble fingers were plying the needle, or knitting yarn that had been carded and spun from Yo Semite-grown wool, with their own hands.

We professed to take turns at reading, aloud, from some mutually interesting book; but the writer discovered that the recurrence came most frequently to the occupant of the large home-made manzanita chair. Remonstrance even only brought back the rejoinder that, as he had no sewing or knitting to do, and was such an excel—etc., etc., reader, it would seem most eminently proper that he should favor the company with another chapter! Sometimes a song, at others a game of whist, or euchre, would add a pleasing variety to the entertainment. Saturday evenings were especially devoted to cards and song, as then our only neighbor, Mr. Lamon, would come out from his hermit-like solitude and grace the circle with his presence, and cheer it with his converse; occasionally dining with us on Sunday afternoons. It may appear almost incredible to confess that, notwithstanding this constant round of seeming sameness and isolation, there was an utter absence of the feeling of loneliness. Many times the query has been put, questioningly, “Do you not feel such entire seclusion from the world oppressive?” and the response was promptly and conscientiously returned, “No. We should, perhaps, if we had time to think about it!”

Thus our long winter evenings and stormy days, while putting us into enjoyable social communion with each other, supplied also the opportunity of conversing with great authors, through their works, of which, fortunately, we had nearly eight hundred volumes, collected, mainly, while publishing the old-time California Magazine. Our summers were made delightful by pleasant converse with the kindliest and most intelligent people upon earth, many of whom were eminent in letters, in science, and in art. Who, then, with this elevating companionship, and its many advantages, united with such sublime surroundings, could help loving the Yo Semite Valley, and being contented with it as a home, even though isolated from the great world outside?

In after years, as residents in the valley became more numerous—and some winters since then we have had over forty, including children—the circle of neighbors proportionately extended, and our divertissements would include parties, sleigh-rides, and snow-shoe excursions.

The spring succeeding the completion of the cabin, called for the cultivation and fencing of a garden-ground, and the planting of an orchard. Many of the trees for the latter were grown from seeds of choice apples that had been sent us, the plants from which were afterwards budded or grafted. In this way a thrifty orchard, of about one hundred and fifty trees, came into being, and now bears many tons, annually, of assorted fruit.

To this, in due time, was added a large strawberry patch, that afterwards became famous from its productiveness and the quality of its fruit. Here perhaps may be given a single illustration of the difficulties to be overcome in such a far-off corner of the earth. The pomological works of the day were full to overflowing with praises of a certain variety of this valuable berry. Specimens were sent for, the price asked accompanying the order. When the plants arrived, owing to the mails of that day coming by Panama, and the necessary delays attending their delivery in the Valley, they were all dried up and dead. Others were ordered, which, upon arrival, were falling to pieces from excessive moisture. The mail-bag containing the next parcel, owing to its too close contact with the steamship’s funnel, was nearly burnt up, and with it the new invoice of strawberry plants. As it is never wise to become discouraged, or to give up until you win, in some form, or prove such a feat to be impossible, still others were sent for; and this time with success, as thirteen living plants rewarded our perseverance. These thirteen small rootlets cost us exactly $45.00. Still, what was that sum in comparison with their future value? With careful culture, these increased to thousands; and many of the largest bunches produced nearly two hundred berries each! In after-times, delicious strawberries could be gathered ad libitum; what, then, was $45.00 for such a luxury? especially when to this is added that of success.

To connect the high ground near the hotel on the south side of the valley with that at the cabin on the north side, and at the same time make the Yo Semite Fall and other attractions accessible to visitors, a causeway was thrown up across the intervening meadow, and an avenue of elms planted on either side, that were grown from seed sent us by the Rev. Joseph Worcester of Waltham, Massachusetts. But few of these now survive, as, during my absence in the mountains on one occasion, some thoughtless young men cut them down for walking-canes, and carried them off. I hope when they see this, they will feel their cheeks warm with shame; but I would not go so far as Young, in his “Night Thoughts,” and say,

“Shame bum thy cheeks to cinders,”

As that would be rather too severe and heavy a penalty.

Owing to the current of events briefly chronicled in the ensuing chapter, necessity, not choice, impelled my absence from the valley for a season; inasmuch as the Board of Commissioners, of that time, became so much angered at my unfaltering persistency in resenting their claims, that they would not even lease to me the old premises, after all other matters had been adjusted, and the title to both land and improvements had legally passed into their hands. They evidently overlooked the fact that I was contending for a home for my family and self, and to which we believed ourselves honorably entitled under a United States general law—a home made sacred, too, by many memories, and where each of our three children were born—and my convictions then, as now, were that any man who would not defend his hearth-stone and his home, to the last drop of his life-blood, when he felt that right was on his side—even when against “forty millions of people,”* [* See chapter XII.] and a half dozen Boards of Commissioners thrown in—belittled his manhood, and proved himself unworthy of the respect accorded to his race. Those very Commissioners, if standing in my place, would (I hope) have acted as I did. It is much to be regretted, however, that some of those men still live, demonstratively, for no other purpose than to perpetuate their old antagonisms. I am their superior in one thing—I have learned to forgive. Life is too short, and too uncertain, to fritter it away in unprofitable and ignoble frictions, and has a holier mission.

By an Act of the State Legislature, at its session of 1880, and a subsequent decision of the Supreme Court, the old Board of Commissioners was retired, and a new one appointed by the Executive in its place, April 19, 1880. The Board elected the writer “Guardian of the Valley;” and, upon my return, Mr. John K. Barnard, the lessee of my old premises, with considerate and large-hearted kindness, again placed the dear old cabin indefinitely at my disposal; and through his continued courtesy, it has been my fondly cherished residence ever since.

But it is not to be supposed that so rare and supernal a flower as unalloyed happiness could ever germinate and bloom in earthly dwellings. This would be to convert terrestrial habitations into celestial. Hence the angel of sorrow, and, alas! of death, with drooping or baneful wings, is frequently, though uninvitedly, permitted to enter human homes and hearts. It was thus with us. Our gifted daughter Florence—given to us during the eventful first year of our residence here, and whose birth was noteworthy from the fact that she was the first white child born at Yo Semite—was called away from us in her eighteenth year, just as she was blooming into womanhood and great prospective usefulness. With agonized hearts, and, seemingly, helpless hands,

“We watched her breathing through the night,

Her breathing soft and low,

As in her breast the wave of life

Kept heaving to and fro

“Our very hopes belied our fears,

Our fears our hopes belied;

We thought her dying when she slept,

And sleeping when she died.”

Nor was ours the only Yo Semite home thus visited at this season; as Effie, the beautiful step-daughter of Mr. J. K. Barnard,

“Passed through glory’s morning gate,

And walked in Paradise.”

Only about thirty days before. The portrayal of this dual loss and affliction, so feelingly presented by my late beloved and gifted wife, Augusta L., is gratefully transcribed from the San Francisco Evening Post, for which she was special correspondent:—

Big Tree Room, Barnard’s Hotel,

Yo Semite Valley, Sept. 28, 1881.

It has seemed that the Angel of Death had overlooked this “gorge in the mountains,” but at length he has learned how sweet were the flowers that bloom in our beautiful valley. First, he came for our lily—sweet, gentle, spiritual Effie, beloved daughter of this house. For a long time he stood afar off, and sent only withering glances and baleful breath, under which she slowly drooped and faded from our sight, till her life passed away with the summer, for on its last day she left us for a home among the angels. Gifted with rare esthetic tastes and talents, which these grand scenes were developing and cultivating, she would doubtless have been prominent among those who shall interpret and perpetuate by their sketches, the poetic beauties of Yosemite. We chose her a final resting place in a grove of noble oaks, where Tissaac, goddess of the valley, keeps constant watch; and the sun’s last rays, reflected from her brow, give each evening their parting benison upon her slumbers, while the singing waters of Cholock* [* The Yo Semite Fall.] murmur an eternal lullaby.

As we were around her grave, rendering the last services, prominent over all, in a band of young friends singing “Safe in the Arms of Jesus,” stood the glorious rose of this wild nature—Florence (“our Floy”), eldest daughter of Mr. Hutchings, guardian of the valley. Full of exuberant, gushing life, she has shed far and wide its fragrance. The child of the valley, for she was the first white child born within these inclosing walls, and the greater part of her life spent here, her whole being was per meated with its influences. Nothing daunted her, nothing gave her so much pleasure as the occasion to help others. Generous, unselfish, her deeds of kindly courtesy will long be remembered by a vast number of visitors, who have enjoyed their benefit and been interested in her blight, original thoughts; for her mind, though unsystematic in its training, was well stocked with good material, and she was rapidly developing into a grand woman.

But again the dread angel looked down, and without waiting to give warning to those who held her close to their hearts, with one fell swoop caught her to his breast, and bore her away; that the Lily and Rose might bloom side by side, in a garden where no frost can blight, no tempest uproot, and the ever-outgoing perfume of their blossoms shall enter our lives to pui* and bless them. So we have laid her, who, only a week before she was called away, was climbing heights and scrambling through ravines where only eagles might be looked for, under the same oaks with Effie; and the dearly loved friends in life, who there seemed to us to be so quietly resting together, are doubtlessly wandering hand in hand through fairer scenes than even these they loved and enjoyed so much.

Oh! the questionings that come up as to the why and the wherefore. As an Indian woman, with a puny, sickly infant, bound in its basket, that has been wailing and whining all its little life of two years, unable even to sit or crawl, came to take a last look at the plucked Rose, I could not but ask myself why such an apparently useless and burdensome existence was allowed to go on, while the helpful, earnest, energetic life had been quenched. But “God knows.”

Mr. Robinson, the artist, from San Francisco, who, in the absence of a clergyman, read the solemn burial service of the Episcopal Church, as Mr. Hutchings had done upon the former sad occasion, read also the following beautiful

Florence Hutchings, born August 23, 1864. Died, September 26, 1881. Of a bold, fearless disposition, warm and generous temperament, far advanced and original in thought beyond her years, with a kind word and pleasant greeting for every one. Always ready to do a self-denying action, or an act of kindness; such was she who now lies cold and pallid before us. She was the first white child ever born in the Yosemite Valley, and the same giant walls that witnessed her birth shall keep watch and ward over her grave through all time. The music of the great Cholock that sang in cheerfulness through her infancy and childhood, shall chant an eternal requiem over her early grave. Here, in her grand and lonely home, where almost every rock, tree, and blade of grass were known to her, and were her playthings and playfellows in childhood, and the objects of her con templation and veneration in youth, shall she lay down to her calm and peaceful rest. Eternal music shall be hers—the winds sighing through the tall pine trees, the murmur of the great water-falls, and the twilight calls of the turtle doves to each other from their far-off homes, the heights Tocoyae* [ * North, and South Domes. ] and Law-oo-Too. All nature unites to lull to rest and peace and quiet the gentle dead. So, friends, temper your griefs to calmness, with the consolation that if the loss is yours, the gain is God’s.

Ahwahnee,* [* The great Indian chief of antiquity.] who could protect its first born in youth and life, will guard her with a loving mother’s embrace in death. Let us leave her in resignation and cheerfulness, knowing that it is but a span between the hour that has called her from us, and the one which is to summon us also to the unknown, whence no one returns. And as she calmly lies, with all nature whispering love and protection over her last resting-place, let us in reverence depart, and leave her soul in joy and peace, safe in the arms of the good and great God who gave it, for so brief a season, to gladden her parents’ hearts, and bloom within the world.

Mr. B. F. Taylor, in his charmingly sunny book, “Between the Gates,” page 238, makes the following suggestion: “Let us give the girl, for her own and her father’s sake, some graceful mountain height, and, let it be called ‘Mt. Florence!’” This complimentary suggestion, through the kindness of friends, has been carried out; as one of the formerly unnamed peaks of the High Sierra now bears the name of “Mt. Florence.” This is best seen and recognized from Glacier Point, and Sentinel Dome.

In less than six brief weeks after our daughter Florence had passed through the Beautiful Gate, the unwelcome angel again visited the old cabin, and this time carried away the devoted and beloved companion of my life, my beloved and devoted wife, after an illness of only a few hours. Without lingering too long upon these chastening experiences, let me add that her endearing qualities may be summed up in one expressive line:—

“Think what a wife should be, and she was that.”

The beautiful gems of art that still adorn our cabin within are nearly all the work of her own hands and skill; and, with many other souvenirs, the creations of her own genius, are ever cherished as sacred memories, memoriā in aeternā.

When the mystic ligature of love joins human hearts, and the vacant chair tells, silently, of the enforced absence of its once loving occupant, bringing back reminders of happy greetings ere You crossed the threshold, as of life’s long summer’s day of joy, to be yours with them no more—it is then, ah! then, that real loneliness strikes home to the heart.

Much of this, however, has been alleviated in past years by the many kindnesses of visitors who have honored and brightened the old cabin with their cheering and refining presence; and to its occupant have given unalloyed pleasure by their refreshing converse. It has been his acceptable pastime for many years to gather any fragmentary curios that were representative of mountain life and circumstances; such, for instance, as the cones and seeds of the different kinds of pine and fir, and other forest trees—including those of the Big Tree with its foliage and wood; specimens of our beautiful ferns, and flowers; Indian relics, with samples of their food; pieces of glacier-polished granite; snow-shoes (of home manufacture), for both valley use and mountain climbing; and those used upon horses for sleigh-riding and hauling over the mountains, and about which more will be said hereafter. In grateful return for the honor of a visit, he has tried to explain these, and given the why and the wherefore concerning them; and, moreover, still cherishes the hope of its indulgence for many years to come.

At the west end of the cabin is a small workshop (a necessary appendage to an isolated life and residence), which also answers for a wood-shed in winter. At the back is another lean-to, which comprises a kitchen, pantry, and store-rooms, and at the eastern end a bedroom. The attic, or roof-room, is sometimes also used as a sleeping apartment—and once, during a heavy flood (to be talked over by and by) as a place of refuge for ourselves and household wares, when the waters were at their highest.

A little west of north from this spot, apparently but a short distance off, while in reality it is nearly three-quarters of a mile away, the Yo Semite Fall makes a leap of over two thousand five hundred feet over the edge of the cliff, and in one bound clears fifteen hundred feet. The surging roll of the music from this fall is a constant and refreshing lullaby to slumber, and never wearies. With so many enduring charms, then, is it a wonder that one clings with admiring fondness to such a home?

Next: Chapter 12 • Index • Previous: Chapter 10

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/11.html