From Kodachrome by G. Gallison

Young mountain coyote near Badger Pass.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Mammals of Yosemite > Flesh-eaters >

Next: Hoofed Mammals • Contents • Previous: Rodents

From Kodachrome by G. Gallison Young mountain coyote near Badger Pass. |

Large, for a coyote, and “tame,” the first impression given by a mountain coyote is that a German shepherd dog is at large in the park. The grizzled, grayish buff color also suggests a timber wolf. True wolves are much larger, of more powerful build, and have not been recorded in our area.

Coyotes are common here, ranging up to the very high country. In winter, they are more numerous in Yosemite Valley, presumably because deep snow reduces the availability of food up high. However, some are at Tuolumne Meadows all winter. It is interesting to see coyotes hunting mice in the snow covered meadows of the valley. They seem to follow the mice by listening to them as they travel under the snow, then pouncing on them in cat-like fashion.

In heavy snow years, coyotes take toll of the fawns or yearling deer, which cannot escape readily in the heavy going. Ordinarily, a healthy, adult deer is a match for a coyote, and has been seen successfully to ward off an attack from two or more, given open ground and good footing. The deer population maintains itself successfully, notwithstanding the fact that the National Park Service gives equal protection to all predators. The usual food of the coyote consists of lesser game, such as rodents, various fruits, and carrion.

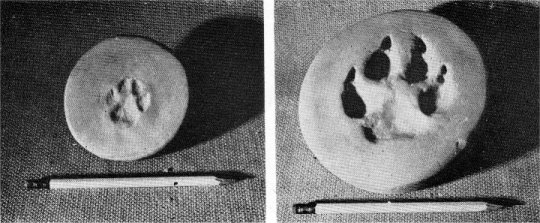

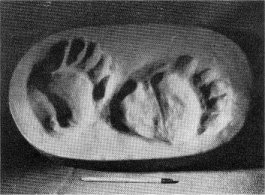

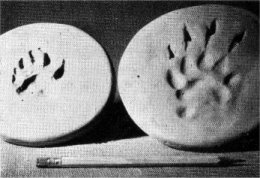

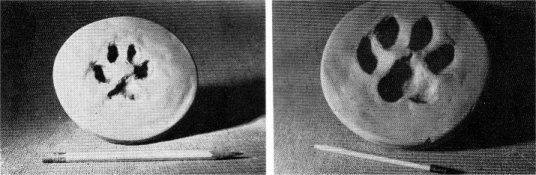

From casts by M. V. Hood Tracks of gray fox, left, and coyote, right. Six-inch pencils. |

The Sierra red fox is a rarity in the park, and few records come to our attention. One was seen at Tuolumne Meadows early in 1952. The gray fox is often mistaken for this species because of certain reddish portions of the coat. The upperparts of the red fox are a yellowish red and it has a large, bushy tail with a white tip.

This species produces the “cross,” “silver” and “black” phases associated with red foxes elsewhere. It is a denizen of the higher elevations and is found more commonly east of the crest, outside the park. It is more numerous in Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks.

Sequoia Natl. Park Photo Gray fox. Note black-tipped tail. |

In the middle and lower elevations of the park, the Townsend gray fox is quite likely to be seen. At night, the car headlights will often pick one up as it scurries away. The first impression may be that it is a cat, for the gray fox is slender and quick.

Sequoia Natl. Park Photo Gray fox pup. |

Visitors seem prone to mistake the gray for a red fox, doubtlessly misled by the reddish color along the sides and base of the neck, together with the reddish flanks. In reality, the larger part of the animal is iron gray, thereby justifying the name. The black stripe along the top of the tail, ending in a black tip, gives conclusive identification for the gray fox. At times, the hoarse, single bark will be clearly heard coming from a rocky hillside. It sounds like a sharp “rawk,” and if one is not close enough to detect the hoarse quality, it may be mistakenly attributed to a “frog” or “night bird.” Often, a fox will emit one bark, then move a short distance and give another. Like other grays, our form has been known to climb trees, especially if the trunk is sloping. They are not animals of the deep forest, however, preferring areas with shrubbery, where they hunt for the small rodents and vegetable matter, particularly berries, which comprise their food. Garbage will not be spurned by them when available.

All the bears now in Yosemite are the Sierra black bear, a subspecies of the American black bear. Several color phases are found, ranging from coal black to light brown or cinnamon. Black phase females often produce brown cubs, or one black and one brown cub, and brown females do likewise.

Population estimates for the 1,189 square miles embracing Yosemite National Park vary between 300 and 400 bears. In summer, there are from 4 to 12 bears living on the valley floor. Under primitive conditions, the area would not be large enough to support over three or four individuals. The higher concentration now present is probably due to the presence of thousands of people, who furnish considerable food through garbage and the larders of unwary campers.

Little is known about the length of life of black bears in the wild. In captivity, bears often live 25 years or more. According to old-time rangers, individual bears in Yosemite are known to have appeared for 15 consecutive years. Most females have their first young when three or four years old. Full growth is not attained, however, until the sixth or seventh year.

Photo by Dixon SIERRA BLACK BEAR |

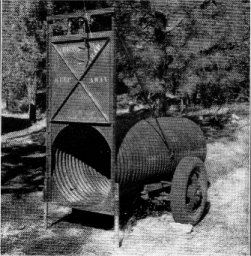

Live trapping of park bears is sometimes practiced in areas where bears are prone to raid food supplies. This is accomplished in a humane manner through the use of a large, iron cylinder, mounted on trailer wheels. There is a trap door in one end, and the bear is enticed into the trap by bait. The trailer can then be coupled to a car and transported to a more remote spot in the park where the bear is released.* [* The material on bears is largely an abridgement of “Bears of Yosemite” by M. E. Beatty, Yosemite Nature Notes 22 (1), January 1943. Mr. Beatty is now (June 1952) Chief Naturalist in Glacier National Park.]

In 1938, a very large male bear was captured in the above manner. This “garbage fed” bear was found to weigh 680 pounds, which, according to all available data, is a record for California.

In late summer and fall bears eat unusually heavily in order to build up heavy layers of fat necessary to carry them through their winter “sleep.” With the first heavy storm of winter most bears go into hibernation. The den is usually a sheltered cave among the rocks, or a hollow tree. They remain until late March or early April, depending on the severity of the winter. They hibernate alone, except where cubs of the year occupy the den with the mother.

As a rule, bears do not eat or drink during the hibernation period. The breaking down of the fatty tissues built up during the previous fall sustains life. However, they have been observed outside their dens during mild winters. Several observations recorded by Yosemite naturalists have indicated that, at this latitude, bears sleep rather lightly during hibernation.

Photo by Anderson The bear trap. |

It has been generally supposed that hibernation was to enable the bears to escape the cold weather of the winter months. Observations in Yosemite indicate, however, that the availability of food during this period is the chief controlling factor.

It is believed that late June is the time when most Yosemite bears mate. Cubs are, for the most part, born around the latter part of January, or early February, while the mother is in hibernation. Cubs are generally born in pairs, although triplets or even solitary cubs are not uncommon. Rarely there are quadruplets.

At birth, they are extremely tiny, weighing less than a pound. Their growth and development are at first very slow. In one case, it was 39 days before the cub opened its eyes. The nursing period lasts for about six months, but the cubs will be with the mother their first year, usually hibernating in the same den with her, or in a den nearby.

In Yosemite, new-born cubs seldom emerge with their mothers until late April, and are rarely observed on the Valley floor before May or June. They are then about 14 inches long, a foot high, and weigh 10 or 12 pounds. They soon supplement their milk diet with other food and put on weight rapidly.

The mother bear is usually quite solicitous of her cubs, fondling and playing with them, and protecting them when in danger. They soon learn to scramble up a tree at the first warning sound from the mother. A mother has been observed cuffing her cubs because they did not go up a tree quickly enough after she had given them a warning of danger.

Despite maternal care, however, as the cubs grow in size, they usually dwindle in number. Sickness and accidents take their toll. The male bear may try to kill or injure any cub that might come within his reach, including his own offspring.

The adult female normally produces young every other year. Cubs hibernating with the mother the winter after their birth will generally be put “on their own” during the second summer when the mother again prepares to mate.

January 28, 1950, a small cub was discovered by the rangers in the area behind Government Center in Yosemite Valley (see back cover). About 17 inches in length and 11 inches high at the shoulder, weighing between 8 and 10 pounds, it could not possibly have been born in the current winter. Yet the presence of small, sharp “milk teeth” characteristic of an animal less than a year old, precludes the idea that it was born in January 1949, the time of the previous cub crop. The logical conclusion based on these facts is that it was born not earlier than August 1949, though the writer (H. C. P.) is unable to find any records of late births for the species in the literature.

Although classed as carnivores (flesh-eaters),

From cast by M. V. Hood Sierra black bear tracks. Front foot, left, hind |

Several cases are known in Yosemite of bears stumbling onto fawns hidden in the tall grass of our meadows, which then, due to their inability to run, fall ready victims. Such instances are rare. New-born fawns are the largest animals killed and eaten by bears in Yosemite. Although essentially nocturnal by nature, some of the bears in Yosemite are active throughout the day. During the warmer parts of the day, the majority will bed down in some secluded spot from which they can quietly slip away if disurbed.

They are good tree climbers, and climb both large and small trees apparently with equal ease, the main requirement being a tree of sufficient size to support the bear’s weight, even though it “teeters.”

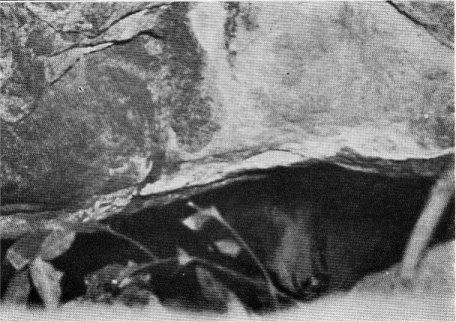

Photo by Cole Bear in den, Indian Canyon |

Bears habitually follow a given route, stepping each time in the footsteps previously made. Trails have been found in Yosemite where they have stepped in the same tracks as their predecessors, until a series of alternating depressions nearly six inches in depth have developed.

Other signs left by bears, besides footprints, consist of bear wallows, rotten logs and stumps ripped apart in the search for insects, turned-over rocks, droppings, and bear trees.

These bear trees are of interest, particularly when the trees happen to be quaking aspen, for they permanently record the marks left by bears. Arriving at such a tree, the bear usually stops, and, standing erect on its hind legs, reaches up as high as possible, biting and scratching the tree. The reason for this action is not definitely known, although writers have suggested that it my be some type of “social register.”

The black bear, being the largest mammal in the park, has practically no natural enemies. The largest bear is generally the boss of his domain until a still larger one comes along to displace him. A female with cubs will sometimes stand against a larger bear, but, as a rule, the smaller bear gives ground without engaging in any serious battle.

Bears have the greatest respect for skunks. On many occasions, our naturalists have observed skunks repeatedly refuse to be outbluffed by a bear. Generally, the bear gives way after a few halfhearted attempts to frighten away the skunk, and allows it to take over the remains of its unfinished meal.

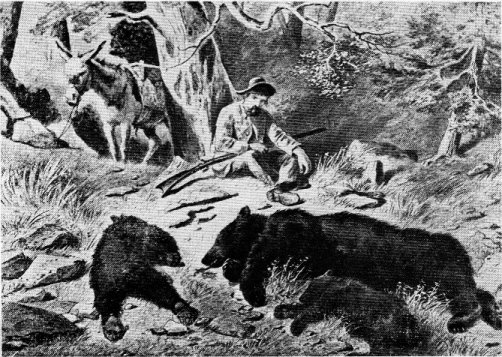

Indiscriminate hunting exterminated the grizzly in California. |

The name “Yosemite” was derived from the Miwok Indian word for grizzly bear. [Editor’s note: For the correct origin of the word Yosemite see “Origin of the Word Yosemite.”—DEA.] One of the earliest accounts of grizzlies in Yosemite is by “Grizzly Adams,” who captured and trained grizzly cubs for his traveling animal show. Adams visited here in the spring of 1854, and, according to his diary, discovered a grizzly bear on the “headwaters of the Merced Rivet.”

The last grizzly known to have been killed in Yosemite was shot “about 1895” at Crescent Lake. The skin of this bear is now in the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California. The last authentic record of the killing of a grizzly in the State of California was in August 1922, in Tulare County.

The grizzly differs f[r]om the black bear both in structure and habits. In general, grizzlies are larger than black bears. It is believed that the Yosemite subspecies, henshawi, was one of the smaller of the California grizzlies.

The external outlines of the mature grizzly differ from the adult black bear in being higher in the shoulder region, giving the appearance of a hump behind the neck. The most reliable field distinguishing character of the grizzly, however, is the length of the front claws, averaging three or more inches, as compared with two inches for a large black bear. The claws of the grizzly are less curved, making it difficult for the adult to climb trees.

It is unfortunate that they are no longer a part of our living wildlife. For them conservation came too late.

THE PRESENT BEAR POLICY AND ITS PROBLEMS

Some thirty years ago visitors to Yosemite Valley considered themselves fortunate to get even a fleeting glimpse of a bear. With the gradual increase in human visitors came a corresponding increase in the number of bears, attracted by the campers’ foodstuffs and by enlarged garbage pits. Soon bears started raiding camps for food, and, after many visitor complaints, the National Park Service began a bear feeding program, the food consisting mainly of garbage scraps.

The result was that the bears would remain throughout the day in the vicinity of the feeding pits which, due to the geography of the valley area, could not be located any great distance away from the main highways. The bears soon turned into beggars, stopping cars, and lining the roadside in hopes of receiving some tid-bits.

To the visitor, the situation seemed ideal. Here was a chance to see bears and to feed them. Few appreciated that these were actually wild animals, with the ability to inflict serious damage to those coming too close to them. Accidents became more frequent until more than sixty hospital cases were recorded during one season.

The service, in an attempt to reduce the number of accidents and to restore normal conditions, then issued a new regulation prohibiting the visitor from feeding, teasing, or molesting the bears. Even this failed to solve entirely the problem.

Nature was badly out of balance. The bears were no longer accustomed to shifting for themselves. The valley was far too small to supply sufficient natural food for such a large population, and so the animals continued to raid camps and garbage cans and to hold up cars. Accidents from bear injuries were still too high.

The policy under which our parks operate in respect to wildlife is to keep conditions as nearly natural as possible. The artificial feeding of bears was therefore not the solution to the problem.

“Bear show” feeding in Yosemite Valley was discontinued in September 1940. A total of 45 bears were trapped during the fall, and moved to outlying areas above the valley rim. This still left too many bears for an area that would hardly supply normal food for more than three or four individuals. Since then, additional bears have been moved; particularly, those individuals that insisted on begging food along highways or were confirmed raiders of camps. No bears were released outside the park boundaries.

Results in general are most encouraging, and accidents from bears have dropped to only a few cases a season. It is hoped that, through this policy, the bear situation will continue to show a steady improvement.

Visitors commonly ask, “Where are the bears? And where can we go to see them?” It is difficult to answer, as bears seldom remain at one fixed spot for any great length of time.

They are often encountered along the roads and trails, in the old apple orchards, or in the campgrounds. Bears on trails faithfully follow every zig and zag, and the hiker had best step off the trail, giving up the right-of-way.

Campers usually have no difficulty seeing bears, particularly, if they have such odorous foods as ham or bacon in their larders. Foodstuffs should be protected by caching in a box or sack and suspending with a rope between two trees, or from a horizontal limb. Make sure the food supply is high enough above the ground so that a bear will be unable to reach it, and far enough away from the tree trunk that the bear can’t reach it by climbing. Bears may break into cars in search of food they can smell there.

Raiding bears can usually be frightened away by loud noises and flashlight beams. It should be remembered, however, that a bear can both outrun and outclimb a human, and that loss of food is preferable to risking serious injuries through too persistent defense of property.

At times, it is possible for the rangers and naturalists to advise visitors as to locations where bears have been recently observed. It is believed that the visitor will get a far greater thrill out of seeing a bear in natural surroundings than in seeing dozens of bears feeding on garbage.

It is dangerous and unlawful to feed, tease, or molest bears in a national park.

[Editor’s note: For current bear safety tips and regulations see http://www.nps.gov/yose/planyourvisit/bears/—DEA.]

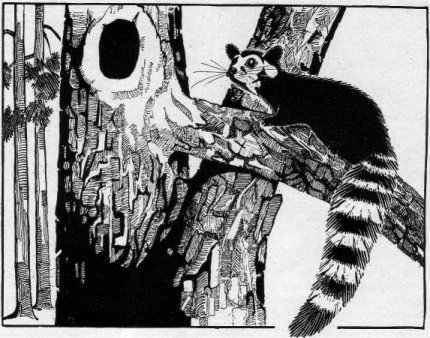

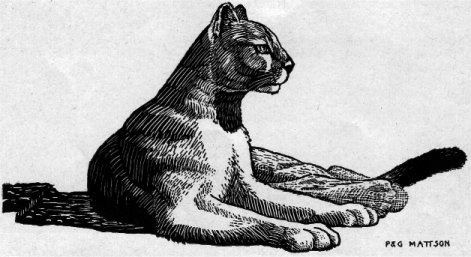

Drawing by C. P. Russell California ring-tailed cat |

Small wonder that the naturalists are often asked to identify the California ring-tailed cat. Seen at night in the headlight beam, the long, bushy, ringed tail and the short legs preclude its being a cat; the squirrel-sized body rules out the raccoon; the head is fox-like. In the dark, the body seems gray, but it is really a light brown. Despite the name, it is not closely related to a cat. It is commonly found at the lower elevations.

Ringtails are entirely nocturnal, seeking their food, rats and mice, at night. They enter buildings, including the attics of Yosemite homes, in this search. Nuts, fruits, and other sweets are also acceptable to these lovely creatures, according to hotel guests who sometimes feed them.

From cast by M. V. Hood Tracks of ring-tailed cat. Six-inch pencil. |

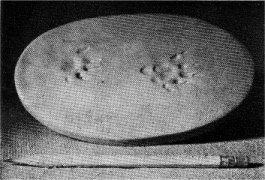

From cast by M. V. Hood Tracks of coon. Front foot, left, hind foot, right. |

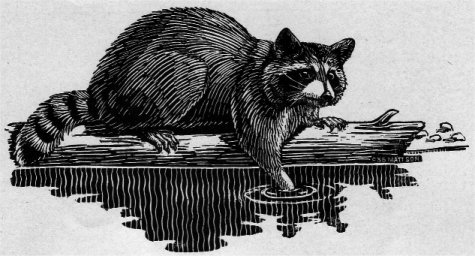

Though uncommon, save in the lower country, the California coon (or “raccoon,” to be affected) is occasionally observed in Yosemite Valley. It is seen more frequently at Wawona and South Entrance (5,130 ft.).

Nocturnal, like the ring-tailed cat, coons are often confused with them. The tail of the coon is much shorter, proportionately, round rather than flattened, and the rings go entirely around it. The ringtail lacks the black mask, and is a much smaller animal.

From “Mammals of Lake Tahoe” by Robert T. Orr, California Academy of Sciences. CALIFORNIA COON |

Contrary to a popular idea, it is not necessary for coons to wash their food before they eat it. While never without some water near by, it is surprising how seeps, or even dribbles, are sufficient for them during the summer drouth. Favorite foods are fish, birds, small mammals, carrion, insects, vegetables, fruits, and acorns. In fact, they will eat “almost anything.”

Drawing by L. M. Smith Mountain weasel. |

The Sierra least weasel is but 8 or 9 inches in length, including the short tail. It can go down a mouse burrow, and undoubtedly does, for mice are one of the chief foods.

Related to the ermine of the Old World, in Yosemite, its upperparts change from brown in summer to white in winter. The range is from the red fir forest above the rim of the Valley on up to the rock slides at timberline.

Chickaree-sized, the mountain weasel has a tail that comprises about half the total length of the animal. In summer, the upper parts are brown, the underparts yellowish or orange. In Yosemite, the winter coat is white overall except for the blackish tip of the tail. Tough, lithe and wiry, weasels can get around into all sorts of places.

Found throughout the middle elevations of the park, mountain weasels are active the year around, day or night. They have been seen between the Yosemite Museum and the Administration Building a Lumber of times. The meadows near Swinging Bridge and Sentinel Bridge are also well-known localities.

The double-distilled essence of courage, mountain weasels will kill anything that they can overcome. Their predominant food is small mammals.

From “Mammals of Lake Tahoe” by Robert T. Orr, California Academy of Sciences. MINK |

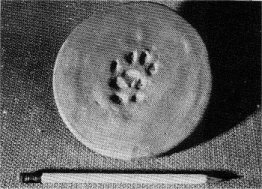

From cast by M. V. Hood Tracks of mink, superimposed. Six-inch pencil. |

The Pacific mink is considered a rare furbearer in Yosemite. It is sometimes found, in suitable territory, at the lower elevations. It is a very dark brown, weasel-like animal, but larger than our weasels and lacking the light underparts displayed by the latter in summer. In winter, our weasels are white. The marten, often mistaken for a mink, has a fox-like face, prominent ears, and an orangy or yellowish throat.

Minks are generally found in or near water. They are good swimmers, so it is not surprising that they feed on fish and frogs. Mice, rabbits and birds are also taken.

Photo by Anderson SIERRA PINE MARTEN |

The Sierra pine marten ranges from the red fir belt up to timberline. The light brown body is about the size of that of a half-grown cat. The fox-like face and the throat patch will separate it from others of the weasel family.

Martens are active day or night, summer and winter. Though forest animals, they are found in Yosemite around high country rockslides and rocky meadows in summer. They eat small rodents and such birds as they can catch.

In winter, when small rodents are under deep snow, martens revert to the forests. There they can travel through the trees with squirrel-like facility. Other tree-dwellers, such as the chickaree, are then caught and eaten.

Like others of the weasel family, martens have scent glands, though the odor is more musky. Only skunks can throw theirs. I believe that the introduction of such scents around the premises of man causes the mouse population to decline noticeably.

From “Mammals of Lake Tahoe” by Robert T. Orr, Courtesy of publisher, California Academy of Sciences. FISHER |

Nowhere common, the fisher is rare in Yosemite. About 3 to 3 feet long, it is a blackish brown with a grizzled effect on the back of the head, shoulders, and along the sides. Often, there is an irregular white spot on the chest. It ranges from the red fir belt on up to the higher country.

Active day or night, summer and winter, the fisher is well adapted for getting prey in trees. It catches squirrels and even pine martens. It successfully kills porcupines. Other rodents, and, probably, some birds are also taken for food, along with occasional vegetable matter.

There are few sight records of the southern wolverine, but, occasionally, tracks are reported in the Yosemite high country. It is terrier-sized, dark brown, with a light band across the forehead, along the sides and across the rump. The back is notably arched, the tail short and the feet well-clawed. It can emit a vile stench.

The footprint is about 5 1/2 inches long, often showing all five toes. The hind portion is divided, rather than a single triangle, unlike any other Yosemite carnivore track that size.

The wolverine has been known to drive away the mountain lion, coyote and bear from their kills. Their food includes carrion, rodents and larger prey. Limited now to a few spots in the Rockies and the Sierra, it is hoped that this interesting member of the native fauna will survive with the protection afforded by the national parks.

Sequoia Natl. Park Photo California badger |

From cast by M. V. Hood Badger tracks. Front foot, left, hind, right. |

Watch for the California badger in the open country of the higher elevations. There it finds a supply of ground squirrels and other rodents available for food, where the digging is easy. This grizzled tan animal is admirably adapted for going underground, with very strong claws and powerful muscles. When waddling along, it looks more like a turtle, but the white streak along the center of the head and neck are quite striking. The scent emitted by a badger is not especially virulent.

A badger digging out a ground squirrel’s nest is interesting to watch. It is not advisable to take liberties with one, for they can inflict severe wounds with their powerful jaws.

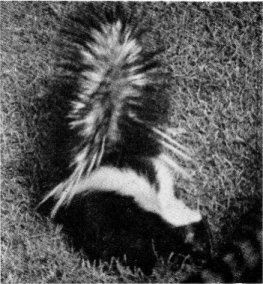

Sequoia Natl. Park Photo California striped skunk. |

Skunks are commoner in lower country, but do live in the park. Despite the fame of their “chemical warfare,” there is no need for fear if you encounter one. The musk is not thrown unless the animal has been startled, or after great provocation. Let him go his way and he’ll do you no harm.

Warning of defense usually comes in this sequence: First, elevation of the tail; next, stamping the front feet on the ground; followed by standing up on the “hands” (in the case of the spotted skunk). The scent can be thrown accurately for about a dozen feet.

From “Mammals of Lake Tahoe” by Robert T. Orr, Courtesy of publisher, California Academy of Sciences. SPOTTED SKUNK |

Two sorts are in Yosemite, the northern California striped skunk and the California spotted skunk (see illustrations). The former is about the size of a cat, the latter half that or less.

The spotted skunk is also known as “civet cat,” but, like “polecat,” that name belongs to an Old World mammal. There is no special tendency toward hydrophobia in this species.

Both species are mainly nocturnal and eat “anything.” Insects, mammals, carrion and fruit are largely the diet. It is doubtful that they go into profound hibernation in this climate.

Despite their chemical defense, skunks are caught and eaten by some predators. Fishers and Pacific horned owls, among others, often take them.

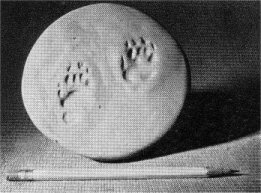

From cast by M. V. Hood Tracks of California spotted skunk. |

From cast by M. V. Hood Tracks of striped skunk. Hind foot on left, |

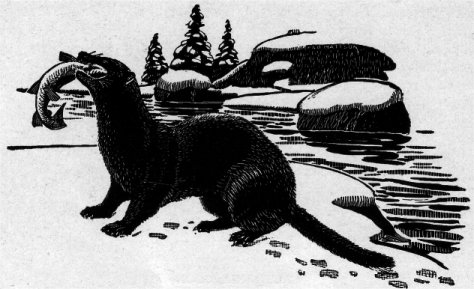

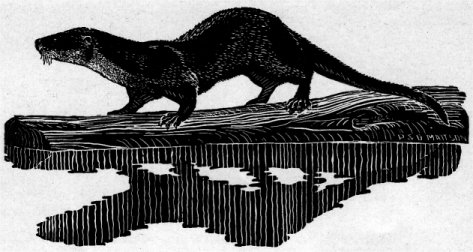

The California river otter is dark brown in color and runs from to 4 feet in length. Otters are well suited to life in the water, with all four feet webbed and the body streamlined. They swim well enough to catch fish and frogs for food. On land, they have a “loping” gait, arching the body greatly.

Uncommon, otters may appear at lakes in the northwest part of the park. They are usually quite shy. They often make slides in mud or snow, leading to the water, and seem to enjoy themselves thoroughly on these “chutes.”

From “Mammals of Lake Tahoe” by Robert T. Orr, Courtesy of publisher, California Academy of Sciences. CALIFORNIA RIVER OTTER |

There are possibly 12 California mountain lions in Yosemite National Park. This need give little alarm to the visitor. Never in park history has one molested a human. Only by good fortune are you likely to see one, because they habitually avoid people. They have been seen along the Wawona Road, in Yosemite Valley, and near Mather. Sometimes tracks are found near Mirror Lake.

A mountain lion is 6 to 8 feet long, tawny, or grayish brown, with a long, rope-like tail. Kittens are spotted and may retain some evidence of this until six months old. The tail is longer than that of young wildcats.

The range in the park is mainly that of the deer. Since deer drop into the country outside the park in winter, lions are often killed there. Therefore, the number in the park is not likely to increase. Besides deer, mountain lions feed on lesser animals.

From “Mammals of Lake Tahoe” by Robert T. Orr, Courtesy of publisher, California Academy of Sciences. CALIFORNIA MOUNTAIN LION |

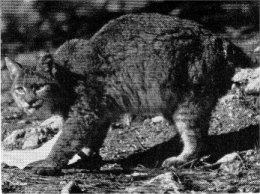

From Kodachrome by Anderson California wildcat kitten |

From Kodachrome by Anderson California wildcat |

California wildcats are far from uncommon in Yosemite. They are from 2 1/2 to 3 feet in total length, including the very short tail which gives rise to another name, “bobcat.” In summer, the general color is tannish brown, but in winter it is much more grayish.

They can easily climb trees, but rocky situations seem to be preferred for dens. However, wildcats have been seen in the open meadows of Yosemite Valley hunting rodents. They often hunt in the daytime, relatively unafraid of man.

The chief food seems to be medium-sized to small mammals and birds, but they also have been known to attack deer, especially when the snow is deep. On at least one occasion, a deer put to flight an attacking wildcat in Yosemite Valley. Fawns are taken very readily, when found.

From casts by M. V. Hood Tracks of California wildcat, left, and California mountain lion, right. Six-inch pencils. |

|

|

Next: Hoofed Mammals • Contents • Previous: Rodents

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/mammals_of_yosemite/flesh_eaters.html