Photo by Harwell

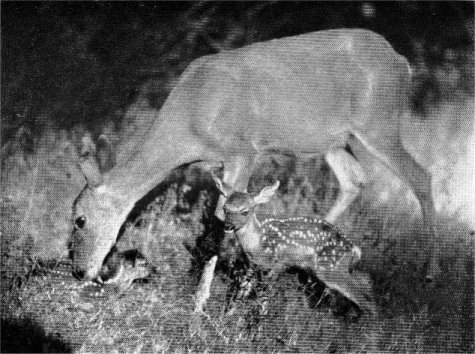

DOE WITH NEWBORN TWIN FAWNS

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Mammals of Yosemite > Hoofed Mammals >

Next: Enjoying Mammals • Contents • Previous: Flesh-eaters

Photo by Harwell DOE WITH NEWBORN TWIN FAWNS |

A delight to the visitor in Yosemite are the “tame” deer. These animals are not domesticated; they are merely unafraid of man.

This concentration of deer in the valley is attributed to “handouts” provided by the increasing number of visitors in the past 35 years. This has probably led the animals to give up the habit of leaving the Valley for the regular wintering grounds each year. Association of humans with food, together with no hunting, accounts for the misleading appearance of tameness.

Until about 1915, deer did not winter in the Valley, but moved out to the western feeding grounds below the park line just as deer from the “wilder” parts of the park now do.

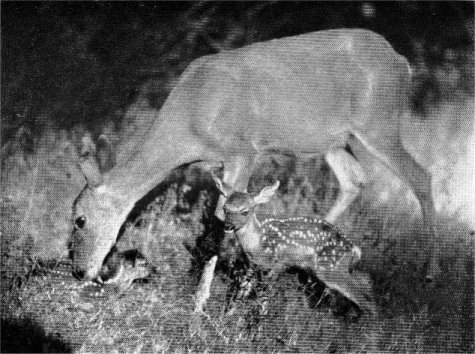

Tails of Yosemite forms of deer. |

Yosemite National Park is a meeting ground for three subspecies—the Rocky Mountain mule, California mule, and Columbian black-tailed deer. It is possible to find animals that display some characteristics of each or mixtures of any two. In sections lying near the normal range of black-tailed and Rocky Mountain mule deer, individuals appear clearly recognizable as to subspecies. For instance, the so-called “granite bucks” of the very high country may usually be identified as of the Rocky Mountain variety. In Yosemite, it is not always possible to rely on field identification of deer.

From Kodachrome by Beatty Buck with growing antlers “in the velvet.” |

Joseph S. Dixon, after over thirty years of observation, felt certain that black-tailed deer always elevate the tail vertically when frightened, while mule deer always hold it below the horizontal under those conditions. He further based identifications on the length of the meta-tarsal gland, which is located on the hind foot above the toes and below the hock or heel. It is at least 5 inches long on mule deer and but slightly over 3 inches on blacktails. This determination can not always be used on certain hybrids.

Because of characteristics which predominate in most of them, we usually refer to the deer of Yosemite Valley as California mule deer, although certain individuals may show some features of the other two forms. Since these are so easily approached, much information about the habits of the California mule deer is available, thanks to patient studies by Dixon, Russell and others. Most of what appears here is drawn from their work.

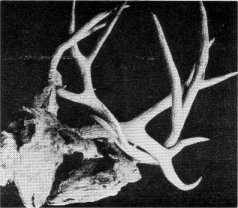

Photo by R. G. Beidleman Buck with one antler shed. Note the scar. |

I have known men to come to the Yosemite Museum and ask us to settle a bet as to whether deer actually shed their antlers! They do shed them, normally once a year.

Deer do not have horns in the true sense of the word. Horns, in most animals that have them, are permanent, not shed seasonally, and are hollow with a bony core. The antlers of deer are solid, bony structures grown anew each year. They should never be referred to as “horns.”

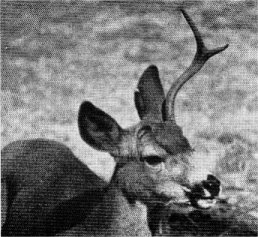

A common misbelief is that the age of bucks (normal does never have antlers) can be told from the number of “points” on one antler. Four points, exclusive of any “eyeguards” is the regular number for a buck in the height of physical development. This is ordinarily attained at the age of four years, but will also continue for several seasons, perhaps until the age of eight. After the years of greatest vigor, the number of points is reduced from year to year until there may be three, two, or one. Thus it is possible for a twelve-year-old buck to carry antlers consisting of only one large spike each!

Hopelessly locked antlers brings lingering death |

As worked out by Dixon, the following sequence of development ordinarily takes place in the antlers of Yosemite deer:

| Yearling | single spike or “forked horn.” |

| Two year old | forked or rarely, three point. |

| Three year old | three pointer, rarely “forked horn.” |

| Four to eight year old | four pointer. |

Females with antlers have been known and certain bucks never lose the velvet from their antlers (called “stags” by hunters), When properly examined, such specimens have proven to be sexually abnormal. It is believed that the male sex hormone governs the production of antlers, but the whole story is not yet known.

“Old Horny” was a buck famous in Yosemite Valley in the 1920’s. He possessed a third short antler growing midway between his eyes and his nostrils. The extra antler was 2 inches high, had a basal diameter of one inch, and developed two, prongs. Later, another “forked horn” buck with a third antler was discovered in Yosemite Valley. He was promptly dubbed “Unicorn Junior”!

The antlers may be shed as early as January and from two to four weeks later, new ones start to grow. The average season for dropping falls in March with new growth started in May.

The new, growing antlers are covered with velvety skin, very rich in nerve and blood supply. Until growth is nearly complete, this “velvet” is quite sensitive. It is not safe to touch it, for the buck might strike out with sharp hoofs, with serious injury to the person taking that liberty.

By July, the first forking of the new antlers has been achieved. Mid-September usually finds the growth completed. The bucks then “horn” brush and small trees to remove the dead velvet, now mainly dead tissue.

In October or November, the rutting, or mating season begins. The necks of the bucks become quite swollen and they are inclined to try out their armament against rivals. Once they have made contact, the fight is usually a “shoving bout,” and when one has been forced to his knees a few times he goes away.

Cases are known where the antlers of the adversaries became permanently interlocked, which ended in death for both. Serious casualties are quite rare, the match seeming merely to determine which buck can drive the other away.

The dominant buck will follow a doe for several days, much of the time with his head thrust stiffly out before him. This behavior culminates in the actual mating, whereupon he selects another doe and repeats the “running” process. Mating season lasts well into January and may extend into February.

From cast by M. V. Hood Deer tracks. Left, fawn; center, very soft mud; |

Rutting season over, the bigger bucks lose their antagonism toward each other. Among younger bucks, antagonism may be displayed at any season.

In Yosemite, most fawns are born in July, but they may arrive as early as June or as late as August. About a quarter of them are twins; very rarely triplets, or even quadruplets, may be born.

For the first week of life, the fawn lies hidden in the tall grass where its spotted pattern blends well, and the mother returns to it for nursing.

The young will not follow its mother in daytime during the first month, but evidence from tracks shows that it may accompany her to water at night after it is six days old.

These habits work for protection. When a lone fawn is found curled up, this does not mean that it has been orphaned; the mother is merely away feeding. Please help us to pass this information on. Each summer, several fawns are brought in to the rangers and the naturalists by misguided visitors who believe they have found an orphan.

The thing to do is to return the animal to where it was found so the doe can reclaim it. Unfortunately, the finders can seldom identify the spot, and we are then faced with a problem. Rearing a baby deer requires two cases of canned milk a month, for which the National Park Service has no funds. The responsibility then devolves upon the employee and constitutes a real financial burden, unfairly imposed. No one who has seen an innocent looking little fawn can bring himself to let it starve.

Even though the fawn may be reared there is another problem. We then have a half-domesticated animal scarcely suitable in a wilderness area such as a national park. Furthermore, when it reaches maturity, especially if a male, it becomes dangerous to little children, often charging them.

Young fawn hidden in meadow. |

If a fawn is found in its resting place, it should be left strictly alone. During the first week it apparently has no odor, which means that the predators are unlikely to discover and destroy it. If a human touches the fawn, of course it is no longer scentless. Even the trail left by persons walking too close to the spot might also lead a curious coyote, mountain lion, wildcat, or bear to the fawn. Some does are very zealous in the protection of their young and have inflicted severe injuries upon people by charging them unexpectedly.

The spotted coat of fawns begins to disappear in August. By the end of September, they are clothed in gray, similar to the color of the adults, which are predominantly blue-gray in winter and reddish in summer.

The Yosemite Valley herd of listless, unafraid deer which do not leave in the winter represent probably less than one per cent of those in the entire park (1189 square miles).

In the autumn, migration of deer from higher to lower country begins. The first big snow storm may initiate this movement, or it may anticipate bad weather. If there is a considerable moderation in weather, some of the deer move back into the park until forced to leave because of the deep snow covering food and making defense against predators difficult or impossible.

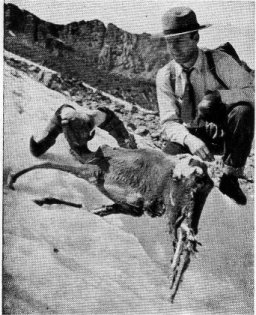

Photo by Harwell Mummified bighorn on the Mt. Lyell Glacier. |

The chief enemy of deer is the mountain lion. A lion is said to average a kill of 50 deer a year. Since we probably have not more than a dozen lions, the annual loss from this source would not be more than 600 deer out of the thousands that are in the park. The animals taken are usually those most susceptible to attack, the old, the crippled, and the less alert. The predators thus help keep the deer herds “thrifty,” except in Yosemite Valley where lions seldom come.

Coyotes, wildcats, and bears also prey on deer, though we have little evidence to prove that they are serious enemies. Coyotes and wildcats will do the most damage when there is extremely heavy or crusted snow, making escape difficult for the deer. Bears may kill a weak or sickly deer, but, as noted above, a spotted fawn is the largest native animal they normally kill for food. All three will clean up the remains of a deer killed by other predators when they can find such a “banquet.”

Golden eagles attack spotted fawns when they can find them away from cover. If the doe is present, she may succeed in protecting her young by standing directly over them. At the close approach of the bird, the mother may attempt to strike at it with the forefeet.

According to Russell, in 1924 and 1925, some 22,000 deer were slaughtered because of the foot and mouth disease epidemic which had affected certain Sierran deer. Those thus removed normally had resorted to the northern part of the park in summer, so for some years afterward deer were scarce in that region. For several seasons a certain number of surplus animals in the valley were captured and released in the sparsely populated area. Whether due to this experiment or to natural influx, the northern deer herd is now considered to contain normal numbers.

Ordinarily, California mule deer eat parts of woody plants, such as leaves, twigs and fruits. However, at certain seasons green grass may form 90 per cent of the food. More than 200 kinds of food have been taken by the different races of mule deer in California. They range in variety from pine needles to acorns.

Nowhere in the natural diet of deer is anything akin to the food offered to them by park visitors. Feeding deer bread, candy and other human foods causes stomach disease which makes the animals sick and may cause their death.

Pampering deer which are regularly fed by hand is dangerous. Several people, including children, have been seriously hurt in national parks by the sharp hooves of does or the antlers of bucks. It is dangerous and unlawful to feed the deer.

Sierra bighorns once lived in the higher parts of what is now Yosemite National Park. However, the park was created too late (1890) to save enough of the “mountain sheep” from the larders of the hunter, sheepherder and miner. They are now all gone.

Grinnell and Storer give the 1870’s as the latest period when bighorns were here, except for stragglers. A few scattered records exist as late as the turn of the century.

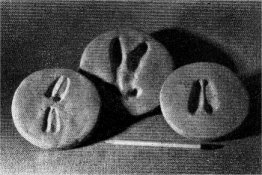

Mountaineers still find horn cases and skulls on the ridges and peaks of the crest. Such locality records are carefully kept at the Yosemite Museum, for they will help to reconstruct the former range of the bighorn. Accordingly, persons finding skull or horns in the park are requested to bring them to the Yosemite Museum. Careful note should be made as to the exact location. Mark it on a topographic map if possible. Even without the specimen, an accurate record of the locality will be of service. [Editor’s note: this statement is out-of-date. Please do not collect skulls, horns, or other artifacts in the park. It is illegal—DEA.]

The Yosemite Museum has on display the mummified body of a bighorn found on the surface of the east lobe of the Mt. Lyell glacier in 1933. Evidence indicates that it fell into the bergschrund at the head of the glacier and was carried in the ice for several centuries until it melted out, 1,936 feet away.

Bighorns still live in the high country of Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks. It is to be hoped that protection there will continue to be successful so that they will always be a living part of the Sierran fauna.

Next: Enjoying Mammals • Contents • Previous: Flesh-eaters

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/mammals_of_yosemite/hoofed_mammals.html