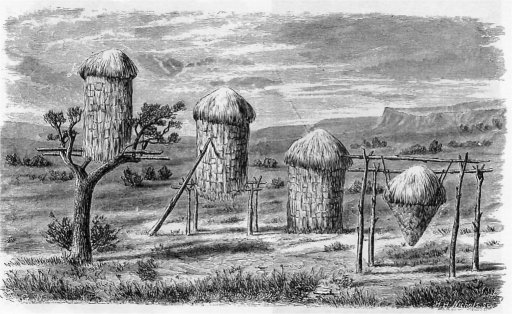

Figure 32. Acorn granaries.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Tribes of Calif. > Mi'-wok >

| Next: Chapter 24 Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Introductory |

By much the largest nation in California, both in population and in extent of territory, is the Miwok, whose ancient dominion extended from the snow-line of the Sierra Nevada to the San Joaquin River, and from the Cosumnes to the Fresno. When we reflect that the mountain valleys were thickly peopled as far east as Yosemite (in summer, still further up), and consider the great extent and fertility of the San Joaquin plains, which to-day produce a thousand bushels of wheat for every white inhabitant, old and young, in certain districts; then add to this the long and fish-full streams, the Mokelumne, the Stanislaus, the Tuolumne, the Merced, the Chowchilla, and the San Joaquin encircling all, along whose banks the Indians anciently dwelt in multitudes, we shall see what a capacity there was to support a dense population. Even the islands of the San Joaquin were made to sustain their quota, for on Feather Island there are said to be the remains of a populous village. The rich alluvial lands along the lower Stanislaus, Tuolumne, and Merced contained the heart of the nation, and were probably the seat of the densest population of ancient California.

And yet, broadly extended as it was, and feeble or wholly lacking as was the feeling of national unity, this people possess a language more homogeneous than many others not half so widely ramified. An Indian may start from the upper end of Yosemite and travel with the sun 150 miles, a great distance to go in California without encountering a new tongue, and on the San Joaquin make himself understood with little difficulty. Another may journey from the Cosumnes southward to the Fresno, crossing, three rivers which the timid race bad no means of ferrying over but casual logs, and still hear the familiar numerals with scarcely the change of a syllable, and lie can sit down with a new-found acquaintance and impart to him hour-long communications with only about the usual supplement and bridging of gesture (which is great at best). To one who has been traveling months in regions where a new language has to be looked to every ten miles sometimes, this state of affairs is a great relief.

There are, as always, many and abrupt dialectic departures, but the root remains, and is quickly caught tip by the Indian of a different dialect. There are not so often whole cohorts of words swinging loose from the language. A ride, through the Nishinam land is like the march of a, regiment through a hostile country; every half-day’s journey there is a clean breach of a whole company of words, which is replaced by another.

For instance, north of the Stanislaus they call themselves mi'-wok (“men” or “people”); south of it to the Merced, mi'-wa; south of that to the Fresno, mi'-wi. On the Upper Merced the word “river” is wa-kal'-la; on the Upper Tuolumne, wa-kal'-u-mi; on the Stanislaus and Mokelumne, wa-kal'-u-mi-toh. This is undoubtedly the origin of the word “Mokelumne”, which is locally pronounced mo-kal'-u-my. So also kos'-sūm, kos'-sūm-mi (salmon) is probably the origin of the word “Cosumnes”, which is pronounced koz'-u-my. For the word “grizzly bear” there exist in different dialects the following different forms: u-zu'-mai-ti, os-o'-mai-ti, uh-zu'-mai-ti, uh-zu'-mai-tuh.

Their language is not lacking in words and phrases of greeting, which are full of character. When one meets a stranger he generally salutes him, wu'-meh? “[Whence] do you come"? After which follows, whi-i'-neh? “What are you at"? Sometimes it is wi'-oh u-kūh'? about equivalent to “How do you do?” How like the savage! Instead of inquiring kindly as to the new comer’s health and welfare, with the inquisitiveness and suspicion of his race he desires to know from what quarter he hails, whither he is going, what for, etc. After the third or fourth question has been asked him, the stranger frequently remarks he'-kang-wa, “I am hungry”, which never fails to procure a substantial response, or as substantial as the larder will permit. Perhaps lie will acknowledge it by ku'-ui, “Thank you”; more probably not. When the guest is ready to take his departure, he never fails to say wūk'-si-mus-si, “I am going”. To which the host replies ko-to-el-le', “You go ahead”, an expression which arises from their custom of walking single file. These rudely-inquisitive greetings are heard only when two Indians meet abroad. At home the stranger is received in silence.

Some of the idioms are curiously characteristic of that point-no-point way of talking which savages have in common with children. Thus, hai'-em is “near”, and hai'-et-kem is also “near”, but not quite so near; and kotun is a “long way off”, though that may be only on the opposite bank of the river. Chu'-to is “good”; chu-to-si-ke' is “very good”, the only comparative expression there is.

While this is undoubtedly the largest, it is also probably the lowest nation in California, and it presents one of the most hopeless and saddening spectacles of heathen races. According to their own confession, in primitive times both sexes and all ages went absolutely naked. All of them north of the Stani[s]laus, and probably many south also, not only married cousins, but herded together so promiscuously in their wigwams that not a few white men believe and assert to this day the monstrous proposition that sisters were often taken for wives. But this is unqualifiedly false. The Indians all deny it emphatically, and not one of their accusers could produce an instance, having been deceived into the belief by the general circumstance above mentioned.

They eat all creatures that swim in the waters, all that fly through the air, and all that creep, crawl, or walk upon the earth, with a dozen or so exceptions. They have the most degraded and superstitious beliefs in wood-spirits, who produce those disastrous conflagrations to which California is subject; in water-spirits, who inhabit the rivers, consume the fish; and in fetichistic spirits, who assume the forms of owls and other birds, to render their lives a terror by night and by day.

In occasional specimens of noble physical stature they were not lacking, especially in Yosemite and the other mountain valleys; but the utter weakness, puerility, and imbecility of their conceptions, and the unspeakable obscenity of some of their legends, almost surpass belief.

But the saddest and gloomiest thing connected with the Miwok is the fact that many of them, probably a majority of all who have any well-defined ideas whatever on the subject, believe in the annihilation of the soul after death. When an Indian’s friend departs the earth, be mourns him with that great and poignant sorrow of one who is without hope. He will live no more forever. All that lie possessed is burned with him upon the funeral pyre, in order that nothing may remain to remind them afterward of one who is gone to black oblivion. So awful to them is the thought of one who is gone down to eternal nothingness that his name is never afterward even whispered. If one of his friends is so unfortunate as to possess the same name, he changes it for another, and if at any time they are compelled to mention the departed, with bated breath they murmur simply it'-teh, “him”. Himself, his identity, is gone; his name is lost; he is blotted out; itteh represents merely the memory of a being that once was. Like all other tribes in California, they are gay and jovial in their lives; but while most of the others have a mitigation of the final terrors in the assured belief of an immortality in the Happy Western Land, the Miwok go down with a grim and stolid sullenness to the death of a dog that will live no more. It is necessary to say, however, that not all entertain this belief. It seems to prevail more especially south. of the Merced, and among the most grave and thoughtful of these. Throughout the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys one will occasionally meet ail Indian who holds to annihilation; but the creed is no where so prevalent as here.

The Miwok north of the Stani[s]laus designate tribes principally by the points of the compass. These are tu'-mun, chu'-much, he'-zu-it, ol'-o-wit (north, south, east, west), from which are formed tribal names as follows: Tu'-mun, Tu'-mi-dok, Ta-mo-le'-ka; Chu'-much, Chūm'-wit, Chu'-mi-dok or Chim'-i-dok, Chūm-te'-ya; Ol'-o-wit, Ol-o'-wi-dok, Ol-o-wi'-ya, etc. Ol-o'-wi-dok is the general name applied by the mountaineers to all the tribes on the plains as far west as Stockton and the San Joaquin.

But there are several names employed absolutely. On the south bank of the Middle Cosumnes are the KÔ'-ni; on Sutter Creek, the Yu-lo'-ni; in Yosemite, the A-wa'-ni; on the South Fork of the Merced, the Nūt'-chu; on the Stanislaus and Tuolumne, the extensive tribe of the Wal'-li; on the Middle Merced, the Ch-ūm-te'-ya; on the Upper Chowchilla River, the Heth-to'-ya; on the Middle Chowchilla, the Chau-clil'-la; on the north bank of the Fresno, the Po'-ho-ni-chi. There were probably others besides on the plains, but they have been so long extinct that their names are forgotten. Dr. Bunnell mentions the “Potoencies”, but no Indian had ever heard of such a tribe; also, the “Honachees”, which is probably a mistake for the Mo-na'-chi, a name applied by some Indians to the Paiuti.

How extremely limited were their journeyings of old may be judged by the fact that all of them, no matter what two rivers they live between, always employ the same phrases: wa-kal'-u-mi tu'-mun (north river), and wa-kal'-u-mi chu'-much (south river). The only fixed name I was ever able to learn was O-tūl'-wi-uh, which is the Tuolumne.

The name “Walli” has been the subject of a great deal of discussion among white men, as to its meaning and derivation. Some assert that it is a word applied by the pioneers to the Indians, without any signification; others, that it is an aboriginal word, denoting “friends”. Probably the latter theory is due to the fact that the Indians, in meeting, frequently cry out “Walli! Walli!” As a matter of fact, it is derived from the word wal'-lim, which means simply “down below”; and it appears to have been originated by the Yosemite Indians and others living high up in the mountains, and applied to the lower tribes with a slight feeling of contempt. The Indians on the Stanislaus and Tuolumne use the term freely in conversing among themselves, but on the Merced it is never beard except when spoken by the whites.

For houses, the Miwok construct very rude affairs of poles and brushwood, which they cover with earth in the winter; in summer, as the general custom is, they move into mere brushwood shelters. Higher up in the mountains they make a summer lodge of puncheons, in the shape of a sharp cone, with one side open, and a bivouac-fire in front of it.

Perhaps the only special points to be noted in their physiognomy are the smallness of many heads, and the flatness on the sinciput, caused by their lying on the hard baby-basket when infants. I felt the heads of a rancheria near Chinese Camp, and was surprised at the diminutive balls which lurked within the masses of hair. The chief, Captain John, was at least seventy years old, yet his head was still perceptibly flattened on the back, and I could almost encircle it with my hands.

Figure 32. Acorn granaries. |

It is generally asserted of these Indians that they will eat anything. But there is one exception, and that is the clean, sweet flesh of the skunk. Old hunters assert that it is such, but the aborigines detest it beyond measure. So uncompromising is their horror of this animal that they have never examined one; consequently they have an erroneous impression of its anatomy. They believe that the effluvium is produced, not by any peculiar secretion, but by the emission of wind! An old hunter related all amusing method of capturing this animal which he bad seen among the Nishinam. One man attracted its attention in front while another ran up quickly behind, seized it by the tail, and by a blow with his hand on the back of the neck broke that organ before the beast could become offensive. The Miwok utilize it in one way at least; they sometimes hang the carcasses on trees along a trail difficult to follow, so that they car be guided by one sense if not by another. I have seen this myself.

They are very fond of hare, and make comfortable robes of their skins. They cut them into narrow slits, dry them in the sun, then lay them close together, and make a rude warp of them by tying or sewing strings across at intervals of a few inches.

Soap-root is used in the manufacture of a kind of glue, and the squaws make brushes of the fibrous matter encasing the bulb, wherewith they occasionally sweep out their wigwams and the earth for a small space around. Although there were millions of tall, straight pines in the mountains, the Miwok had no means of crossing rivers, except logs or clumsy rafts. All the dwellers on the plains, and as far up as the cedar-line, bought all their bows and many of their arrows from the upper mountaineers. An Indian is ten days in making a bow, and it is valued at $3, $4, and $5, according to the workmanship; an arrow at 121 cents. Three kinds of money were employed in this traffic. White shell-buttons, pierced in the center and strung together, rate at $5 a yard (this money was less valuable than among, the Nisbinam, probably because these lived nearer the source of supply); “periwinkles” (olivella?) at $1 a yard; fancy marine shells at various prices, from $3 to $10 or $15 a yard, according to their beauty.

Their chieftainship, such as it is, is hereditary when there is a son or brother of commanding influence, which is very seldom; otherwise be is thrust aside for another. He is simply a master of ceremonies, except when a man of great ability appears, in which case he sometimes succeeds in uniting two or three of the little, discordant tribelets around him, and spends his life in a vain effort to harmonize others, and so goes down to his grave at the last broken-hearted. It is of no use; the greatest savage intellect that ever existed could not have banded permanently together fifty villages of the California Indians.

When be decides to hold a dance in his village, he dispatches messengers to the neighboring rancherias, each bearing a string wherein is tied a number of knots. Every morning thereafter the invited chief unties one of the knots, and when the last one is reached they joyfully set forth for the dance—men, women, and children.

Occasionally there arises a great orator or prophet, who wields a wide influence, and exerts it to introduce reforms which seem to him desirable. Old Sam, of Jackson, Calaveras County, was such a one. Sometimes he would set out on a speaking tour, traveling many miles in all directions, and discoursing with much fervor and eloquence nearly all night, according to accounts. Shortly before I passed he had introduced two reforms, at which the reader will probably smile, but which were certainly salutary so far as they went. One was that the widows no longer tarred their heads in mourning, but painted their faces, which would be less lasting in its loathsome effects. The other was that instead of holding all annual “cry” in memory of the dead, they should dance and chant dirges.

In one of his speeches to his people he is reported to have counseled them to live at peace with the whites, to treat them kindly, and avoid quarrels whenever possible, as it was worse than useless to contend against their conquerors. He then diverged into remarks on economy in the household: “Do not waste cooked victuals. You never have too much, anyhow. The Americans do not waste their food. They work hard for it, and take care of it. They keep it in their houses out of the rain. You let the squirrels get into your acorns. When you eat a piece of pie, you eat it up as far as the apple goes, then throw the crust into the fire. When you have a pancake left You throw it to the dogs. Every family should keep only one dog. It is wasteful.”

Tai-pok'-si, chief of the Chimteya, was a notable Indian in his generation, holding undisputed sovereignty in the valley of the Merced, from the South Fork to the plains. Early every morning, as soon as the families had had time decently to prepare breakfast, be would step out before his wigwam and lift up his sonorous voice like a Stentor, summoning the whole village to work. in the gold-diggings, and himself went forth to share the labor of the humblest. Men, women, and children went out together, taking their dinners along, and the village was totally deserted until about three o’clock Every one worked hard, inspired by the example of their eat chieftain, the men making dives in the Merced of a minute or more, and bringing up the rich gravel, while the women and children washed it on shore. They got plenty of gold and lived in civilized luxury so long as Taipoksi was alive. He was described by one who knew him well as a magnificent specimen of a savage, standing fully six feet high, straight and sinewy, shiny-black as an Ethiopian, with eyes like an eagle’s, a lofty forehead, nostrils high and strongly chiseled, each of them showing a clean, bold ellipse. He died in 1857, and was buried in Rum Hollow with unparalleled pomp and splendor. Over 1,200 Indians were present at his funeral. After this grand old barbarian was gone his tribe speedily went to the bad; their industry lagged; their gold was gambled away; their fine clothing followed hard after it; dissension, disease, and death scattered them to the four winds.

Among the Miwok a bride is sometimes carried to the lodge of her husband on the back of a stalwart Indian, amid a joyous throng, singing songs, dancing, leaping, and whooping. In return for the presents given by the groom, his father-in-law gives the young couple various substantial articles, such as are needful in the scullery, to set them up in housekeeping. In fact, here, as generally throughout the State, it is a pretty well established usage that the parents are to do everything for their children, and the latter nothing until they marry. The father often continues these presents of meat and acorns for several years after the marriage. And what is his reward? Making himself a slave, he is treated substantially as such, and when he has become old, and ought to be tenderly nurtured, he frequently has to shift for himself.

Mention is made of a woman named Ha-u-chi-ah', living near Murphy’s, who, in 1858, gave birth to twins and destroyed one of them, in accordance with the universal custom.

Some of their shamans are men and some women. Scarification and prolonged suction with the mouth are their staple methods. In case colds and rheumatism they apply California balm of Gilead (Picea grandis) externally and internally. Stomachic affections and severe travail treated with a plaster of hot ashes and moist earth. They think that their male shamans or sorcerers can sit on a mountain top, fifty miles distant from a man whom they wish to destroy, and accomplish that result by filliping poison toward him from their finger-ends. The shaman’s prerogative is that be must be paid in advance; hence a man seeking his services brings his offering with him, a fresh-slain deer, or so many yards of shell-money, or something, and flings it down on the ground before him without a word, thereby intimating that he desires the equivalent of that in medicine and treatment. The patient’s prerogative is that if he dies his friends may kill the physician.

In the acorn dance the whole company join hands and dance in a circle, men and women together—a position of equality not often accorded to the weaker sex. They generally have to dance by themselves in an outside circle, each woman behind her lord. Besides this fixed anniversary there are many occasional fandangoes, for feasting and amusement. They resemble a civilized ball somewhat, inasmuch as the young men of the village giving the entertainment contribute a sum of money wherewith to procure a great quantity of hare, wild-fowl, acorns, sweet roots, and other delicacies (nowadays generally a bullock, sheep, flour, fruit, etc.). Then they select a sunny glade, far within some sequestered forest where they will not be disturbed by intruders, and plant green branches in the ground, forming large circle. Grass and pine-straw are scattered within to form at once divan and a dancing-floor. Here the invited villagers collect and spend frequently a week; gambling, feasting, and sleeping in the breezy shade by day, and by night dancing to lively tunes, with execrable and most industrious music, and wild, dithyrambic crooning of chants, and indescribable dances, now sweeping around in a ring beneath the overhanging pine-boughs, and now stationary, with plumes nodding and beadery jingling. It is wonderful what a world of riotous enjoyment the California Indians will compress into the space of a week.

They observe no puberty dance, neither does any other tribe south of Chico.

There is no observance of the dance for the dead, but an annual mourning (nūt'-yu) instead; and occasionally, in the case of a high personage, a special mourning, set by appointment a few months after his death. One or more villages assemble together in the evening, seat themselves on the ground in a circle, and engage in loud and demonstrative wailing, beating themselves and tearing their hair. The squaws wander off into the forest wringing their arms piteously, beating the air, with eyes upturned, and adjuring the departed one, whom they tenderly call “dear child”, or “dear cousin” (whether a relative or not), to return. Sometimes, during a kind of trance or frenzy of sorrow, a squaw will dance three or four hours in the same place without cessation, crooning all the while, until she falls in a dead faint. Others, with arms interlocked, pace to and fro in a beaten path for hours, chanting weird death-songs with eldritch and inarticulate wailings—sad voicings of savage, hopeless sorrow.

On the Merced the widow does not apply pitch over the whole face, but only in a small blotch under the ears, while the younger squaws singe off their hair short. When some relative chances to be absent at the time of the funeral some article belonging to the deceased (frequently a hat nowadays) is preserved from the general sacrifice of his effects and retained until the absent member returns, that the sight of it may kindle his sorrow and awaken in his bosom fresh and piercing recollections of that being whom he will never more behold.

On the Lower Tuolumne, after dancing the frightful death-dance around the fresh-made grave into which the body has just been lowered, they go out of mourning by removing the pitch until the annual mourning comes round, when they renew it. On the latter occasion they make out of clothing and blankets manikins to represent the deceased, which they carry around the graves with shrieks of sorrow.

As soon as the annual mourning is over in autumn all the relatives of the departed are at full liberty to engage in their ordinary pursuits, to attend dances, etc., which before that were interdicted. That solemn occasion itself too frequently winds up with a gross debauch of sensuality. The oldest brother is entitled to his brother’s widow, and lie may even convey her home to his lodge on the return from the funeral, if he is so disposed, though that would be accounted a very scandalous proceeding.

Although cremation very generally prevailed among the Miwok there never was a time when it was universal. Captain John states that long before they had ever seen any Europeans, the Indians high up in the mountains buried their dead, though his people about Chinese Camp always burned. As low down on the Stanislaus as Robinson’s Ferry long ranks of skeletons have been revealed by the action of the river, three or four feet beneath the surface, doubled up and covered with stones, of which none of the bones showed any charring.

In respect to legends, they relate one which is somewhat remarkable. First it is necessary to state that there is a lake-like expansion of the Upper Tuolumne some four miles long and from a half mile to a mile wide, directly north of Hatchatchie Valley (erroneously spelled Hetch Hetchy). It appears to have no name among Americans, but the Indians call it O-wai'-a-nuh, which is manifestly a dialectic variation of a-wai'-a, the generic word for “lake”. Nat. Screech, a veteran mountaineer and hunter, states that he visited this region in 1850, and at that time there was a valley along the river having the same dimensions that this lake now has. Again, in 1855, lie happened to pass that way and discovered that the lake bad been formed as it now exists. He was at a loss to account for its origin; but subsequently he acquired the Miwok language as spoken at Little Gap, and while listening to the Indians one day lie overheard them casually refer to the formation of this lake in an extraordinary manner. On being questioned they stated that there had been a tremendous cataclysm in that valley, the bottom of it having fallen out apparently, whereby the entire valley was submerged in the waters of the river. As nearly as he could ascertain from their imperfect methods of reckoning time this occurred in 1851; and in that year, while in the town of Sonora, Screech and many others remembered to have heard a huge explosion in that direction which they then supposed was caused by a local earthquake.

On Drew’s Ranch, Middle Fork of the Tuolumne, lives an aged squaw called Dish-i, who was in the valley when this remarkable event occurred. According to her account the earth dropped in beneath their feet and the waters of the river leaped up and came rushing upon them in a vast, roaring flood, almost perpendicular like a wall of rock. At first the Indians were stricken dumb and motionless with terror, but when they saw the waters coming they escaped for life, though thirty or forty were overtaken and drowned. Another squaw named Isabel says that the stubs of trees, which are still plainly visible deep down in the pellucid waters, are considered by the old superstitious Indians to be evil spirits, the demons of the place, reaching up their arms, and that they fear them greatly. This account, if authentic, is valuable as throwing some light on the origin of Yosemite and other great canons of the high Sierra.

An Indian of Garrote narrated to me a myth of the creation of man and woman by the coyote, which contained a very large amount of aboriginal dirt. When the legends of the California Indians are pure, which they generally are, they are often quite pretty; but when they diverge into impurity they contain the most gratuitous and abominable obscenity ever conceived by the mind of man.

The following is a fable told at Little Gap:

After the coyote had finished all the work of the world and the inferior creatures lie called a council of them to deliberate on the creation of man. They sat down in an open space in the forest, all in a circle, with the lion at the head. On his right sat the grizzly bear, next the cinnamon bear, and so on around according to the rank, ending with the little mouse, which sat at the lion’s left.

The lion was the first to speak, and he declared he should like to see man created with a mighty voice like himself, wherewith he could frighten all animals. For the rest he would have him well covered with hair, terrible fangs in his claws, strong talons, etc.

The grizzly bear said it was ridiculous to have such a voice as his neighbor, for he was always roaring with it and seared away the very prey lie wished to capture. He said the man ought to have prodigious strength, and move about silently but very swiftly if necessary, and be able to grip his prey without making a noise.

The buck said the man would look very foolish, in his way of thinking, unless be had a magnificent pair of antlers on his head to fight with. He also thought it was very absurd to roar so loudly, and he would pay less attention to the man’s throat than be would to his ears and his eyes, for he would have the first like a spider’s web and the second like fire.

The mountain sheep protested be never could see what sense there was in such antlers, branching every way, only to get caught in the thickets. If the man had horns mostly rolled up, they would be like a stone on each side of his bead, giving it weight, and enabling him to butt a great deal harder.

When it came the coyote’s turn to speak, he declared all these were the stupidest speeches he ever heard, and that be could hardly keep awake while listening to such a pack of noodles and nincompoops. Every one of them wanted to make the man like himself They might just as well take one of their own cubs and call it a man. As for himself he knew he was not the best animal that could be made, and he could make one better than himself or any other. Of course, the man would have to be like himself in having four legs, five fingers, etc. It was well enough to have a voice like the lion, only the man need not roar all the while with it. The grizzly bear also had some good points, one of which was the shape of his feet, which enabled him easily to stand erect; and he was in favor, therefore, of making the man’s feet nearly like the grizzly’s. The grizzly was also happy in having no tail, for he had learned from his own experience that, that organ was only a harbor for fleas. The buck’s eyes and ears were pretty good, perhaps better than his own. Then there was the fish, which was naked, and which he envied, because hair was a burden most of the year; and lie, therefore, favored a man without hair. His claws ought to be as long as the eagle’s, so that he could hold things in them. But after all, with all their separate gifts, they must acknowledge that there was no animal besides himself that had wit enough to supply the man; and he should be obliged, therefore, to make him like himself in that respect also—cunning and crafty.

After the coyote had made an end, the beaver said he never heard such twaddle and nonsense in his life. No tail, indeed! He would make a man with a broad, flat tail, so he could baul mud and sand on it.

The owl said all the animals seemed to have lost their senses; none of them wanted to give the man wings. For himself, he could not see of what use anything on earth could be to himself without wings.

The mole said it was perfect folly to talk about wings, for with them the man would be certain to bump his head against the sky. Besides that, if he had eyes and wings both, he would get his eyes burnt out by flying too near the sun; but without eyes he could burrow in the cool, soft earth, and be happy.

Last of all, the little mouse squeaked out that he would make a man with eyes, of course, so he could see what he was eating; and as for burrowing in the ground, that was absurd.

So the animals disagreed among themselves, and the council broke up in a row. The coyote flew at the beaver, and nipped a piece out of his cheek; the owl jumped on top of the coyote’s head, and commenced lifting his scalp, and there was a high time. Every animal set to work to make a man according to his own ideas; and, taking a lump of earth, each one commenced molding it like himself; but the coyote began to make one like that be had described in the council. It was so late before they fell to work that nightfall came on before any one had finished his model, and they all lay down and fell asleep. But the Cunning coyote staid awake and worked hard on his model all night. When all the other animals were sound asleep, lie went around and discharged water on their models, and so spoiled them. In the morning early he finished his model and gave it life long before the others could make new models; and thus it was that man was made by the coyote.

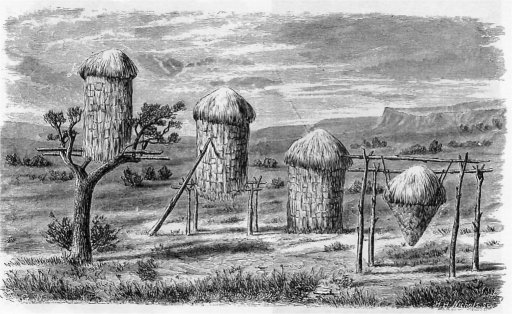

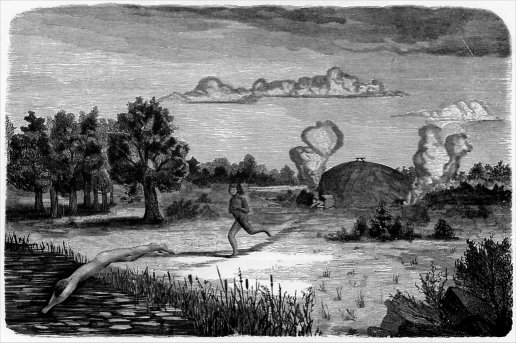

Figure 34. A sweat and cold plunge |

Following are the Miwok numerals, as spoken in Yosemite. There are slight variations everywhere, but the only one of importance is found on Calaveras River, where lu'-teh is substituted for keng'-a.

|

One. Two. Three. Four. Five. |

keng'-a. o-ti'-ko. to-lok'-o. o-i'-sa. ma-cho'-ka. |

Six. Seven. Eight. Nine. Ten. |

ti-mok'-a. tit-oi'-a. kÔ-win'-ta. el-le'-wa. na-a'-cha. |

| Next: Chapter 24 Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Introductory |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/powers/23.html