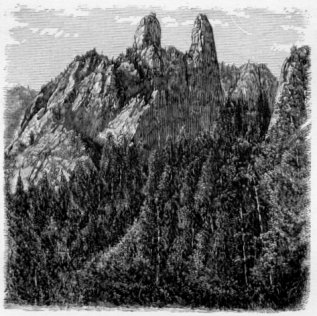

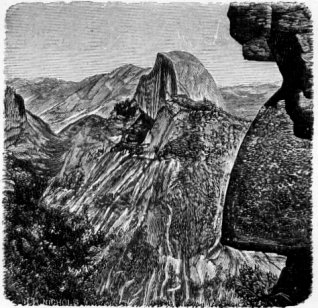

Figure 35. Pu-sí-na-chuk-ha.

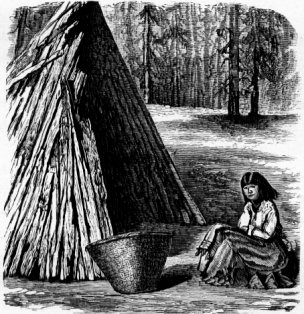

(Squirrel and acorn granary).

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Tribes of Calif. > Yosemite >

| Next: Pai-u'-ti • Contents • Previous: Chapter 23 The Mi'-wok |

There is no doubt the Indians would be much amused if they could know what a piece of work we have made of some of their names. As stated in the Introduction, all California Indian names that have any significance at all must"be interpreted on the plainest and most prosaic principles; whereas the great, grim walls of Yosemite have been made by the white man to blossom with aboriginal poetry like a page of “Lalla Rookh”. From the “Great Chief of the Valley” and the “Goddess of the Valley” down to the “Virgin Tears” and the “Cataract of Diamonds”, the sumptuous imaginations of various discoverers have trailed through that wonderful gorge blazons of mythological and barbarian heraldry of an Oriental gorgeousness. It would be a pity, truly, if the Indians had not succeeded in interpreting more poetically the meanings of the place than our countrymen have done in such bald appellations as “Vernal Fall”, “Pigeon Creek”, and the like; but whether they did or not, they did not perpetrate tbe melodramatic and dime-novel shams that have been fathered upon them.

In the first place the aborigines never knew of any such locality as Yosemite Valley. Second, there is not now and there has not been anything in the valley which they call Yosemite. Third, they never called “Old Ephraim” himself Yosemite, nor is there any such a word in the Miwok language.

The valley has always been known to them, and is to this day, when speaking among themselves, as A-wa'-ni. This, it is true, is only the name of one of the ancient. villages which it contained; but by prominence it gave its name to the valley, and, in accordance with Indian usage almost everywhere, to the inhabitants of the same. The word “Yosemite” is simply a very beautiful and sonorous corruption of the word for “grizzly bear”. On the Stanislaus and north of it the word is u-zú-mai-ti; at Little Gap, o-so'-mai-ti; in Yosemite itself, u-zú-mai-ti; on the South Fork of the Merced, uh-zú-mai-tuh.

Mr. J. M. Hutchings, in his “Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California", states that the pronunciation on the South Fork is “Yohamite”. Now, there is occasionally a kind of cockney in the tribe, who cannot get the letter “h” right. Different Indians will pronounce the word for “wood” su- sú-eh, sú-suh, hu-hú-eh; also, the word for “eye”, hun'-ta, hun'-tum, shun'-ta. It may have been an Indian of this sort who pronounced the word that way; I never beard it so spoken.

In other portions of California the Indian names have effected such slight lodgment in our atlases that it is seldom worth while to go much out of the way to set them right; but there are so many of them preserved in Yosemite that it is different. Professor Whitney and Mr. Hutchings, in their respective guide-books, state that they derived their catalogues of Indian names from white men. The Indians certainly have a right to be heard in this department at least; and when they differ from the interpreters every right-thinking man will accept the statement of an intelligent aborigine as against a score of Americans. The Indian can very seldom give a connected, philosophical account of his customs and ideas, for which one must depend on men who have observed them; but if he does not know the simple words of his own language, pray who does?

Acting on this belief, I employed Choko (a dog), generally known as Old Jim, and accounted the wisest aboriginal head in Yosemite, to go with me around the valley and point out in detail all the places. He is one of the very few original Awani now living; for a California Indian, he is exceptionally frank and communicative, and he is generally considered by Americans as truthful as he is shiftless, a kind of aboriginal Sam Lawson. His statements and pronunciations I compared with those of other Indians, that the chances of error might be as much reduced as possible. In the following list the signification of the name is given whenever there is any known to the Indians.

Wa-kal'-la (the river). Merced River.

Kai-al'-a-wa, Kai-al-au'-wa, the mountains just west of El Capitan.

Pūt'-pūt-on, the little stream first crossed on entering the valley on the north side.

Lung-u-tu-ku'-ya, Ribbon Fall.

Po'-ho-no, Po-ho'-no, (though the first is probably the more correct), Bridal-Veil Fall. In Hutchings’s Guide-Book, it is stated that the Indians believe this stream and the lake from which it flows to be bewitched, and that they never pass it without a feeling of distress and terror. Probably the Americans have laughed them out of this superstition, as it certainly is not now perceptible. This word is said to signify “evil wind”. The only “evil wind” that an Indian knows of is a whirlwind, which is poi-i'-cka or kan'-u-ma.

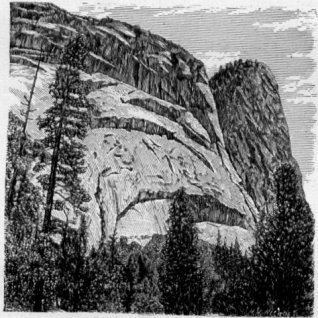

Tu-tok-a-nu'-la, El Capitan. This name is a permutative substantive formed from the verb tūl-tak'-a-na, to creep or advance by degrees, like a measuring-worm. This may, therefore, be called the “Measuring-worm Stone”, of which the origin will be explained in the legend given below.

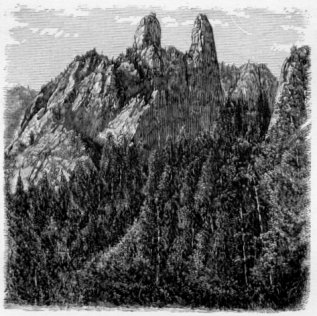

Ko-su'-ko, Cathedral Rock.

Figure 35. Pu-sí-na-chuk-ha. (Squirrel and acorn granary). |

Kom-pom-pe'-sa, a low rock next west of Three Brothers. This is erroneously spelled “Pompompasus”, applied to Three Brothers, and interpreted “mountains playing leap-frog”. The Indians know neither the word nor the game.

Loi'-a, Sentinel Rock.

Sak'-ka-du-eh, Sentinel Dome.

Cho'-lok (the fall), Yosemite Fall. This is the generic word for “fall”.

Ūm'-mo-so (generally contracted by the Indians to Ūm'-moas or Ūm'-mo), the bold, towering cliff east of Yosemite Fall. According to Choko, there was formerly a hunting-station near this point, back in the mountains, where the Indians secreted themselves to kill deer when driven past by others. If we may credit him, they missed more than they hit. In his jargon of English, Spanish, and Indian, supplemented with copious and expressive pantomime, he described how they hid themselves in the booth, and how the deer came scurrying past; then lie quickly caught up his bow and shot, shot, shot; then peered out of the bushes, looked blank, laughed, and cried out, “All run away; no shoot um deer!”

Ma'-ta (the cañon), Indian Cañon. A generic word, in explaining which the Indians hold up both hands to denote perpendicular walls.

Ham'-mo-ko (usuall'y contracted to Ham'-moak), a generic word, used several times in the valley to denote the broken débris lying at the foot of the walls.

U-zu'-mai-ti Lâ'-wa-tuh (grizzly-bear skin), Glacier Rock. The Indians give it this name from the grayish, grizzled appearance of the wall and a fancied resemblance to a bear-skin stretched out on one of its faces.

Tu-tu'-lu-wi-sak, Tu-tūl'-wi-ak, the southern wall of South Cañon.

Figure 36. Cho-ko-nip-o-deh. (baby-basket). |

Tol'-leh, the soil or surface of the valley wherever not occupied by a village; the commons. It also denotes the bank of a river.

Pai-wai'-ak (white water?), Vernal Fall. The common word for “water” is kik'-kuh, but a-wai'-a means “a lake” or body of water. I have detected a conjectural root, pai, pi, denoting “white”, in two languages.

Yo-wai'-yi, Nevada Fall. In this word also we detect the root of awaia.

Tis-se'-yak, South Dome. This is the name of a woman who figures in a legend related below. The Indian woman cuts her hair straight across the forehead, and allows the sides to drop along her cheeks, presenting a square face, which the Indians account the acme of female beauty; and they think they discover this square face in the vast front of South Dome.

To-ko'-ye, North Dome. This rock represents Tisseyak’s husband. On one side of him is a huge, conical rock, which the Indians call the acorn-basket that his wife threw at him in anger.

Shun'-ta, Hun'-ta (the eye), the Watching Eye.

A-wai'-a (a lake), Mirror Lake.

Sa-wah' (a gap), a name occurring frequently.

Wa-ha'-ka, a village which stood at the base of Three Brothers; also, that rock itself. This was the westernmost village in the valley, and the next one above was

Sak'-ka-ya, on the south bank of the river, a little west of Sentinel

Hok-ok'-wi-dok, which stood very nearly where Hutchings’s Hotel now stands, opposite Yosemite Fall.

Ku-mai'-ni, a village which was situated at the lower end of the great meadow, about a quarter of a mile from Yosemite Fall.

A-wa'-ni, a large village standing directly at the foot of Yosemite Fall. This was the ruling town, the metropolis of this little mountain democracy, and the giver of its name, and it is said to have been the residence of the celebrated chief Ten-ai'-ya.

Ma-che'-to, the next village east, at the foot of Indian Cañon.

No-to-mid'-u-la, a village about four hundred yards east of Macheto.

Le-sam'-ai-ti, a village standing about a fifth of a mile above the last-mentioned.

Wis-kul'-la, the village which stood at the foot of the Royal Arches, and the uppermost one in the valley.

Figure 37. Yosemite Lodge |

This is not only a true Indian story, but it has a pretty meaning, being a kind of parallel to the fable of the bare and the tortoise that ran a race. What all the great animals of the forest could not do the despised measuring-worm accomplished simply by patience and perseverance. It also has its value as showing the Indian idea of the formation of Yosemite, and that they must have arrived in the valley after it bad assumed its present form. It should be remarked that the word tultakana means both the measuring-worm and its way of creeping.

We turn now to the legend of Tis-se'-yak. As it stands in Hutchings’s Guide-Book it was written by S. M. Cunningham, one of the earliest settlers in the valley, who first printed it in an eastern newspaper. It is a thousand pities to back and slash in such a miserable way this somewhat tropical legend, but fidelity to aboriginal truth compels me to do it. In its present shape it is a production quite too embellished to have originated in a California Indian’s imagination, hence it is not representative, not illustrative. Tisseyak, instead of being a “goddess of the valley”, was a very prosaic and commonplace woman, who was beaten by her husband because she drank the water before him; and the picture of Indian life revealed in that action, however rude and brutal it may be, is wholly concealed in the story as Mr. Cunningham wrote it.

Figure 38. Tis-se'-yak. |

South Dome is the woman and North Dome is her husband, while beside the latter is a lower dome which represents the basket. The acme of female beauty is reached in the fashion of cutting off the hair straight across the top of the forehead, and allowing the side-locks to droop beside the ears; and the Indians fancy they discover this square-cut appearance on the face of the South Dome. Probably the only significance of this little story is a reference to some severe drought that once prevailed in the valley.

There are other legends in Yosemite, including one of a Mono maiden who loved an Awani brave and was imprisoned by her cruel father in a cave until she perished; also one of the inevitable lover’s leap. But neither Choko nor any other Indian could give me any information touching them, and Choko dismissed them all with the contemptuous remark, “White man too much lie.”

| Next: Pai-u'-ti • Contents • Previous: Chapter 23 The Mi'-wok |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/powers/24.html