Red Fir Cone

Slightly More Than 1/2 Natural Size

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Trees > Red Fir >

Next: Giant Sequoia • Contents • Previous: White Fir

[Pine Family]

Abler magnifica Murr.

Red Fir Cone Slightly More Than 1/2 Natural Size |

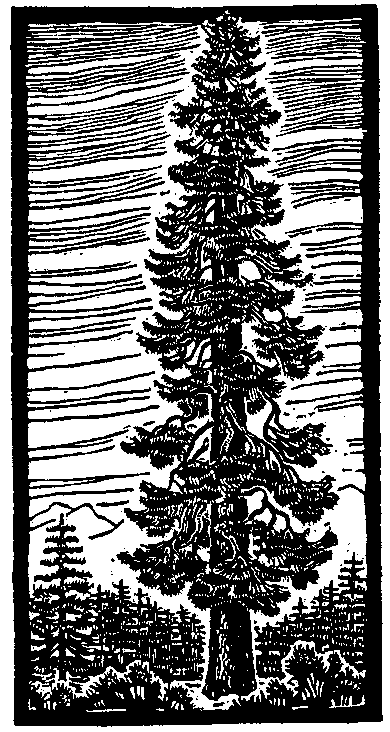

Red Fir Tree |

The Red Fir takes its common name from the bark of the mature tree, which is almost of a chocolate color, with a decided reddish tinge in the sunshine. Its Latin name is descriptive of the impression it makes upon the beholder. The rich coloring of the bark, the architectural effect of the shaft, and the heavy sprays of foliage make it truly one of the most magnificent of all our trees.

Its blue-green needles range from three-quarters of an inch to an inch in length, growing all around the branch, but seeming to curve from opposite sides, after the manner of the firs. The needles are sessile; that is, they are attached directly to the twig without a leaf-stem. They are curved, often in a sickle shape, especially so upon the upper branches, and are slightly thickened, so that they are four-sided instead of flat. The cones are from four to eight inches in length, slightly larger than those of the White Fir, but similar in shape; like them, they break up on the tree, leaving the woody axis. When ripe they are brown with a purplish bloom.

The Red Fir is a dweller upon the mountainsides of the Canadian Zone, where it reaches a height of one hundred and seventy-five feet, with a massive, column-like trunk two to five feet in diameter. In a dense forest, the shaft is clear of branches for fifty or seventy-five feet, and the crown is gradually rounded off; most of the lower branches are horizontal or slightly inclined, with their fan-like layers of needles; but as they become shorter, forming this conical crown, they tend to turn upward.

On a sunshiny March day they are especially striking, with their heavy sprays laden with snow, icicles hanging from them, while under the branches the reddish-purple of the staminate flowers stands out against the glistening white.

There are a few young Red Firs on the floor of the Valley; several are grouped around the giant Ponderosa Pine, and there are others on the Lost Arrow Trail, near the Yosemite Creek footbridge. They are rather scrubby specimens, but below Gin Flat, on the Big Oak Flat Road, is a stand of the fresh young saplings, beautiful as the morning. Bordering the Glacier Point Road just above Mono Meadows is a forest of splendid mature trees, readily accessible; on the ridge which runs from Mount Watkins to the Tioga Road at Snow Flat is another.

A brief review of differences between the Red Fir and the White Fir may be of service. The bark gives a primary distinction but it is one that applies only to mature trees. In both species it is then rough and deeply furrowed, but in the Red Fir it has a dark red or even purplish cast and the surface is more narrowly broken by rounded ridges, divided irregularly by diagonal fissures, while in the White Fir the color is ashen to dark gray, with brown in the clefts and shadows. In cross section the inner wood of the former is red, that of the latter pale, and more subject to decay. Red Fir bark is good bonfire wood; it is the wood which is burned down to glowing coals nightly for the firefall from Glacier Point.

Young trees of both kinds have a whitish or silvery bark, the Red Fir particularly so. When they are under close comparison, young branchlets of the White Fir seem more yellowish-green and are smooth and bald, whereas those of the Red Fir are often minutely hairy with a rather rusty effect.

The needles of the Red Fir are shorter, on the average; the difference in length is perhaps more pronounced on the lower branches. In color they are darker and definitely more bluish-green. By a twist in the short leaf-stem or petiole the White Fir needles appear to grow straight out on both sides of the twig, while the needle of the Red Fir is sessile; that is, it is directly attached to the twig on a foot that is thickened ever so slightly, contracted—again, ever so slightly— above, and the needle. itself tends to curve upward. The needle of the White Fir is flat, with a midrib below, while that of the Red Fir, though smaller, is sufficiently thickened to seem four-sided.

When both are ripe the cones of the Red Fir are larger than those of the White Fir; their brown has a purplish cast rare in the White Fir, usually a brown tinged with olive or chrome.

As the Red Fir mingles with the White along its lower borders, so it does with the Mountain Hemlock at the upper edge of the Red Fir’s territory. On the Forsyth Pass Trail between Lake Tenaya and Little Yosemite, for example, the slope toward Tenaya Lake has an abundance of Mountain Hemlock. It is a northerly exposure where the snow lies long, at an altitude ranging from 8,200 to 10,000 feet. Across the ridge, where the exposure is to the south and the sun, the Red Fir is the dominant tree, with some admixture of Western White Pine.

The bark of the Red Fir is much more deeply furrowed than that of the Mountain Hemlock, although the coloring is not dissimilar—a little more red in the fir, perhaps. The trunk of the hemlock is somewhat smaller, and while the Red Fir branches carry the great flat sprays of foliage so often noted, those of the Mountain Hemlock are plumy and drooping, even to the leader at its narrow spire of a top. Both have bluish-green needles, but those of the former are sessile; those of the latter grow all around the branch on short leaf-stems and are much blunter.

Next: Giant Sequoia • Contents • Previous: White Fir

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/trees_of_yosemite/red_fir.html