K STREET

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Up & Down Calif. > 1862 Chapter 1 >

| Next: Chapter 2 • Contents • Previous: Book 2 |

BOOK III

1862

Floods—Sacramento under Water—The Money Question—A Muddy Journey to San Jose—Results of the Floods—The Chinese.

San Francisco.

Sunday, January 19, 1862.

The rains continue, and since I last wrote the floods have been far worse than before. Sacramento and many other towns and cities have again been overflowed, and after the waters had abated somewhat they are again up. That doomed city is in all probability again under water today.

The amount of rain that has fallen is unprecedented in the history of the state. In this city accurate observations have been kept since July, 1853. For the years since, ending with July 1 each year, the amount of rain is known. In New York state—central New York—the average amount is under thirty-eight inches, often not over thirty-three inches, sometimes as low as twenty-eight inches. This includes the melted snow. In this city it has been for the eight years closing last July, 21 3/4 inches, the lowest amount 19 3/4 inches, the highest 23 3/4. Yet this year, since November 6, when the first shower came, to January 18, it is thirty-two and three-quarters inches and it is still raining! But this is not all. Generally twice, sometimes three times, as much falls in the mining districts on the slopes of the Sierra. This year at Sonora, in Tuolumne County, between November 11, 1861, and January 14, 1862, seventy-two inches (six feet) of water has fallen, and in numbers of places over five feet! And that in a period of two months. As much rain as falls in Ithaca in two years has fallen in some places in this state in two months.1

The great central valley of the state is under water—the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys—a region 250 to 300 miles long and an average of at least twenty miles wide, a district of five thousand or six thousand square miles, or probably three to three and a half millions of acres! Although much of it is not cultivated, yet a part of it is the garden of the state. Thousands of farms are entirely under water—cattle starving and drowning.

Benevolent societies are active, boats have been sent up, and thousands are fleeing to this city. There have been some of the most stupendous charities I have ever seen. An example will suffice. A week ago today news came down by steamer of a worse condition at Sacramento than was anticipated. The news came at nine o’clock at night. Men went to work, and before daylight tons of provisions were ready—eleven thousand pounds of ham alone were cooked. Before night two steamers, with over thirty tons of cooked and prepared provisions, twenty-two tons of clothing, several thousand dollars in money, and boats with crews, etc., were under way for the devastated city.

You can imagine the effect it must have on the finances and prosperity of the state. The end is not yet. Many men must fail, times must be hard, state finances disordered. I shall not be surprised to see our Survey cut off entirely, although I hardly expect it. It will be cut down, doubtless, and some of the party dismissed. I see no help, and on whom the blow will fall remains to be seen. I think my chance is good, if the thing goes on at all, but I feel blue at times.

I finished my geological report on Tuesday, it is 250 pages on large foolscap, besides maps, sketches, etc. I have my botanical and agricultural work yet to do.

San Francisco.

Friday, January 31.

We have had very bad weather since the above was written, but it has cleared up. In this city 37 inches of water has fallen, and at Sonora, in Tuolumne, 102 inches, or 8 1/2 feet, at the last dates. These last floods have extended over this whole coast. At Los Angeles it rained incessantly for twenty-eight days—immense damage was done—one whole village destroyed. It is supposed that over one-fourth of all the taxable property of the state has been destroyed. The legislature has left the capital and has come here, that city being under water. This will give us a better chance for our appropriation, but still the prospect looks blue. There is no probability that we will get enough to carry on work with our full corps.

Wednesday, January 29, was the Chinese New Year, and such a time as they have had! I will bet that over ten tons of firecrackers have been burned. Their festivities last three days, closing tonight. This is their great day of the year. They claim that their great dynasty began 17,500 and some odd years ago Wednesday—a pedigree that beats even that of the “first families of Virginia.”

All the roads in the middle of the state are impassable, so all mails are cut off. We have had no “Overland” for some weeks, so I can report no new arrivals. The telegraph also does not work clear through, but news has been coming for the last two days. In the Sacramento Valley for some distance the tops of the poles are under water!

San Francisco.

February 9.

I wrote you by the last steamer and also sent a paper. I have sent a paper by each steamer for some time and will send another by this. A mail now occasionally gets in, but many letters and papers must have been lost. For papers and printed matter the “Overland” is a total failure.

Since I last wrote the weather has been good and the waters in the great valleys have been receding, but there is much water still. I have heard many additional items of the flood. Judge Field, of Sacramento City, said a few days ago that his house was on the highest land in the city and that the mud was two feet deep in his parlors after the water went down. Imagine the discomforts arising from such a condition of things.

An old acquaintance, a buccaro, came down from a ranch that was overflowed. The floor of their one-story house was six weeks under water before the house went to pieces. The “Lake” was at that point sixty miles wide, from the mountains on one side to the hills on the other. This was in the Sacramento Valley. Steamers ran back over the ranches fourteen miles from the river, carrying stock, etc., to the hills.

Nearly every house and farm over this immense region is gone. There was such a body of water—250 to 300 miles long and 20 to 60 miles wide, the water ice cold and muddy—that the winds made high waves which beat the farm homes in pieces. America has never before seen such desolation by flood as this has been, and seldom has the Old World seen the like. But the spirits of the people are rising, and it will make them more careful in the future. The experience was needed. Had this flood been delayed for ten years the disaster would have been more than doubled.

The telegraph is now in working order, and we had news this morning—up to 5 P.M. last night from St. Louis—surely quick work. But the roads will long be impassable over large portions of the state.

San Francisco.

Monday, February 10.

An assistant in the zo÷logical department was stung by a stingaree so badly in his foot that he has been very lame the last six weeks and came to the city a short time ago. As he will be nearly helpless for some time yet he is going East by this steamer and I will send this by him to be mailed in New York.

We can get no information as to whether our money will be on hand the first of March, as has been promised, or not.

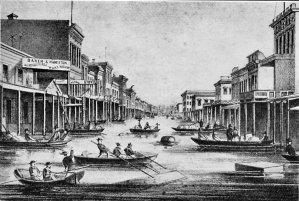

K STREET |

J STREET THE CITY OF SACRAMENTO IN THE FLOOD OF 1862 From contemporary newspaper cuts |

Rates have risen here to three per cent a month lately, which shows how hard the money market is. It has been but one and a half per cent up to the last month.

San Francisco.

March 9.

As the “money question” just now engrosses more of my thoughts than any other subject, I may be pardoned if I tell you something about it, for “out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaketh.”

The act which created the Survey appropriated $20,000 to begin it, and the next legislature added $15,000 to continue it. That would have carried us on until about May of this year. The treasury was then in good condition, and all looked well. Ten thousand dollars was handed over at the start, and $10,000 more came on during the first year of our work. But scoundrels interfered with the treasury. A transfer of $250,000 from one fund to another deranged state finances so that we could realize none of our last appropriation, but as it was necessary to carry on the work and the money was promised in the fall, Professor Whitney borrowed money to go on with the work. Fall came, but none of the promised funds. We must wait until March, then till May. None of the state officers had received their salaries during the latter part of the last year, but before they left office, the Comptroller and the Treasurer hit on a plan to relieve their own cases and that of their fellows. Taxes are paid in twice a year, spring and fall. They called in, in advance, over $250,000 in the fall, not due until spring, and thus paid off all their back salaries and the claims of certain friends. A part of this money belonged to the Interest Fund, supposed to be kept inviolate for payment of the interest on the state debts; about $110,000 or $115,000 of this was used, and of this, $86,000 is still out, to be paid out of the first moneys due the treasury.

The new set of officers came in, but couldn’t be paid. The Assembly seized on $60,000 of a select fund, the Swamp Land Fund, and are now trying for $100,000 more, and will doubtless take it. If they do, the Lord only knows when we will be paid. With this new move, I went to Sacramento three days ago and had a long and confidential talk with the Treasurer, who is an old friend of mine here, and found out all this and much more, the upshot of which is, that we will probably have to wait until next December for our pay! The state now owes me $1,400, a thousand of which was solemnly and surely promised before this time. Professor Whitney is still worse off, for he has borrowed several thousand dollars to carry on the work. You need not wonder that I fell blue—disgusted, indignant, and mad. I had hoped for better things, that the rule of scoundrelism in the state was over—it is not over—but “still lives.” I have no fears of not getting it at some time, it is provided for by special appropriation, and, of the last $15,000, $10,000 are audited and stand first on the list of claims from the General Fund. There is no talk of repudiation—only, we can’t get our money when it is due.

Meanwhile, the most influential state officers are all favorably disposed toward our work, and see its immense importance to the material interests of the state, but this doesn’t pay us for past labors. Yet I have hopes that something will be done to relieve the state, and with its relief, I hope for our relief.

The floods have still more deranged finances and make some action imperative. The actual loss of taxable property will amount to probably ten or fifteen millions, some believe twice that, but I think not even the latter sum. The Treasurer says that the next tax list will cut down the taxable property about one-third of the whole amount, or probably about fifty million dollars, as each man will get as much taken off on his property as is possible. I suppose the actual loss in all kinds of property, personal and real, will rank anywhere between fifty and a hundred million dollars—surely a calamity of no common magnitude!

On Saturday, March 1, Ashburner left for the East on business of the Survey, to do some chemical work there. He wanted to visit the New Almaden Mines before he sailed, so Saturday, February 22, I started with him to make the proposed visit. It was a rainy, wet, dull day, but the city was gay with flags, for it was Washington’s Birthday. The shipping in the harbor was even gayer than the city itself.

We took steamer to Alviso, at the head of the Bay of San Francisco, then stage for seven miles to San Jose. The roads were awful. We loaded up, six stages full, in the rain, and had gone scarcely a hundred rods when the wheels sank to their axles and the horses nearly to their bellies in the mud, when we unloaded. Then the usual strife on such an occasion. Horses get down, driver swears, passengers get in the mud, put shoulders to the wheels and extricate the vehicle. We walk a ways, then get in, ride two miles, then get out and walk two more in the deepest, stickiest, worst mud you ever saw, the rain pouring. I hardly knew which grew the heaviest, my muddy boots or my wet overcoat. Then we ride again, then walk again, and finally ride into town, having made the seven miles in four hours’ hard work. The pretty village was muddy, cheerless, and dull beyond telling, but I called on Mr. and Mrs. Hamilton and had a pleasant time.

We intended to take stage to New Almaden the next day, but finding the roads so muddy, and the rain continuing, we feared being shut up there, so resolved to come back on Monday. Sunday I heard Hamilton preach, called on a friend and lunched, then took dinner and spent the evening with Mr. Hamilton.

The next day we started back and had the usual amount of walking in the mud, but it did not rain. We got within two and a half miles of the boat, where we found a stream had broken over its banks and had made a new bed and had cut up the road so that it was impossible to get across with the stages. After much delay a part of the passengers got across on the backs of horses, some getting down, and all thoroughly wet. Ashburner went on, I went back with our carpetbags. We had gone back a mile or two in the mud, when a man overtook us on horseback saying a boat had come up to take the ladies and baggage across. So the stages turned back. But on arriving at the break we found the boat gone, and after another delay, we again started for town, where we arrived in due time, having consumed over seven hours in that muddy operation. Hamilton chanced to meet me at the stage office, and insisted on my going to his house, which I did, and spent two days there. I came back on Wednesday, when the water had fallen so that stages could cross.

San Jose has not suffered with floods, but much by too wet weather. Roads are impassable, and nearly a million pounds of quicksilver has accumulated on hand, the roads being too muddy to get it to Alviso. It was still very wet. Apricot trees were in blossom, and the hills began to look green. The foothills had suffered with drought the last few years and the artesian wells in the valley had begun to fail. They will work well enough now, I think, for a few years at least.

Ashburner got off on Saturday and much we miss him, I assure you. He was a jolly good fellow, good at a joke, goodnatured, philosophical, and with a great fund of humor and of anecdote.

Last week we got word of a worse condition of the treasury than we had anticipated, so I started immediately for Sacramento to see the Treasurer. Some of the results I have given in the first part of this letter, but of the trip some items may be of interest.

I left here at 4 P.M. on Thursday, March 6, by steamer. Night came on before we reached the mouth of the Sacramento River, but it was a glorious afternoon and the views of the mountains were lovely before sunset. I went to my berth early, but some gamblers were playing within a few feet of me until near morning, and it was but poor sleep that I got. Early in the morning I went to a hotel in Sacramento and got my breakfast and brushed up for business. That dispatched, I had some time to look at the city. Such a desolate scene I hope never to see again. Most of the city is still under water, and has been for three months. A part is out of the water, that is, the streets are above water, but every low place is full—cellars and yards are full, houses and walls wet, everything uncomfortable. Over much of the city boats are still the only means of getting about. No description that I can write will give you any adequate conception of the discomfort and wretchedness this must give rise to. I took a boat and two boys, and we rowed about for an hour or two. Houses, stores, stables, everything, were surrounded by water. Yards were ponds enclosed by dilapidated, muddy, slimy fences; household furniture, chairs, tables, sofas, the fragments of houses, were floating in the muddy waters or lodged in nooks and corners—I saw three sofas floating in different yards. The basements of the better class of houses were half full of water, and through the windows one could see chairs, tables, bedsteads, etc., afloat. Through the windows of a schoolhouse I saw the benches and desks afloat.

It is with the poorer classes that this is the worst. Many of the one-story houses are entirely uninhabitable; others, where the floors are above the water are, at best, most wretched places in which to live. The new Capitol is far out in the water—the Governor’s house stands as in a lake—churches, public buildings, private buildings, everything, are wet or in the water. Not a road leading from the city is passable, business is at a dead standstill, everything looks forlorn and wretched. Many houses have partially toppled over; some have been carried from their foundations, several streets (now avenues of water) are blocked up with houses that have floated in them, dead animals lie about here and there—a dreadful picture. I don’t think the city will ever rise from the shock, I don’t see how it can. Yet it has a brighter side. No people can so stand calamity as this people. They are used to it. Everyone is familiar with the history of fortunes quickly made and as quickly lost. It seems here more than elsewhere the natural order of things. I might say, indeed, that the recklessness of the state blunts the keener feelings and takes the edge from this calamity.

It was rainy, dull day. I left the city at 2 P.M. Friday, and as I came down the river saw the wide plain still overflowed, over farms and ranches—houses here and there in the waste of waters or perched on some little knoll now an island.

San Francisco.

March 16.

We have had severe storms in the mountains, and for near two weeks the telegraph was stopped, but on Thursday news again began to come, and on Friday the word was that Manassas was occupied by Federal troops. The city was wilder with excitement thatn I have seen it before over war news. The legislature adjourned. The streets were filled. From the top of our building a hundred flags could be counted floating in the stiff breeze. Hurrahs were heard in the streets, and as night came on a hundred guns were fired on the plaza, the bands in the theaters played patriotic tunes, the streets were crowded with people—out in front of every bulletin board were black masses of men straining their necks and eyes to see if anything new was posted. Saturday brought confirmations of the news and the excitement did not go down, flags were flying, boys and Chinese exploded firecrackers, and columns in the papers teemed with telegraphic news that had accumulated along the way during the break. I trust that the way is opened now for a speedy close of this unfortunate war.

We have had more heavy rains since I last wrote, and when we can get out again, if we get out at all, I don’t know. It is time for the rains to cease, but they don’t.

I have long deferred writing about the Chinese in California, and will now devote a few words to them, as it may be a matter of some interest. What the “Nigger Question” is at home, the “Mongolian Question” is here.

As you all know there is a great Chinese immigration to this state. But they come not as other immigrants, to settle; they come as other Californians come, to make money and return. Every Chinaman expects to return, and even if he dies here, his body is returned for burial in the “Celestial” land. Dead Chinamen form an important item of freight on every ship leaving this port for China. It is estimated that there are at least fifty thousand Chinese in the state, and many authorities rate the number still higher; this would make about one-sixteenth to one-eighteenth of the whole population. They all land here, and from three to five thousand live in this city. Whole streets are devoted to them. But most of them are at work over the country—most of the placer mining in the state is in their hands. They come here a “peculiar people,” and stay so: they very seldom learn the language, and they adopt none of the customs of the country. They come with all the faults and vices of a heathen people, and these are retained here.

I wish you could walk with me through the Chinese part of the city. All the trades and professions go on as at home; they have their aristocracy and their masses, their big men and their poor ones, their fine stores and their poor groceries, but all is in true Chinese style. Although the houses are American, they are fitted up Chinese and furnished Chinese. Signs hang out in Chinese, and the cragged Chinese characters are written on everything. In the better class of shop they have also an English sign. These are some I copied: Sam Loe, Ning Lung Co., Wau Kee, Wing Yung, Yang Wo Poo, Tsun Kee, Kip Sing, Hee Sun, Wau Hup, Hang Kip & Co., Hong Yun, Chung Shung & Co., Hing Soong & Co., Lun Wo, Tong Yue, Tin Hop. In this evening’s paper I read that a murder was committed this morning in the city—Ah Choe killed Ah On. There is, at times, a Chinese theater, and there has been, and may possibly be yet, a temple for their worship.

They keep up their old customs and dress here, as well as their language. Men wear their long hair braided into a “tail,” which is either done up around the head or hangs down to the heels behind. These are held in the greatest veneration; a man losing his “tail” falls into disgrace upon returning to his own country, and it is made a crime now under the laws of this state for anyone to cut off a Chinaman’s “tail.”

The morals of this class are anything but pure. All the vices of heathendom are practiced. The women are nearly all the lowest prostitutes, and there seems no way of improving them. They are outside of all the ordinary means. There is a mission station, with a chapel, but it fails to reach the masses. I was there a few Sundays ago, but understood but little. There were about forty or fifty Chinamen, the missionary, and his wife. The service was entirely in Chinese, all the audience, except myself, Chinese. In front of me sat a rich Chinese merchant, his finger nails over an inch long, looking like the huge talons of some bird of prey; but, with him, emblems that he did no hard work. For the Chinese wear long finger nails, as Americans wear certain styles of dress, to show that they are above work.

NOTES

1. A table of the monthly rainfall in San Francisco for the five years, 1860 to 1864, will be useful for reference here and throughout Professor Brewer’s Journal. The figures are from Alexander McAdie’s The Clouds and Fogs of San Francisco (1912). Rainfall variesy between different parts of the state, but the San Francisco figures may be taken as a general index of conditions throughout central California at least.

| Month | 1860 | 1861 | 1862 | 1863 | 1864 |

| January | 1.64 | 2.47 | 24.36 | 3.63 | 1.83 |

| February | 1.60 | 3.72 | 7.53 | 3.19 | 0.00 |

| March | 3.99 | 4.08 | 2.20 | 2.06 | 1.52 |

| April | 3.14 | 0.51 | 0.73 | 1.61 | 1.57 |

| May | 2.86 | 1.00 | 0.74 | 0.23 | 0.78 |

| June | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | |

| 6 Months | 13.32 | 11.86 | 35.61 | 10.72 | 5.70 |

| July | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| August | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.21 |

| September | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| October | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| November | 0.58 | 4.10 | 0.15 | 2.55 | 6.68 |

| December | 6.16 | 9.54 | 2.35 | 1.80 | 8.91 |

| —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | |

| 6 Months | 7.86 | 13.66 | 3.02 | 4.38 | 15.94 |

| Annual | 21.18 | 25.52 | 38.63 | 15.10 | 21.64 |

| Seasonal | 22.27 | 19.72 | 49.27 | 13.74 | 10.08 |

Annual rainfall is from January to December; seasonal rainfall is from July to June. The seasonal rainfall for the twelve months ending June 30, 1862, is the heaviest on record; the lightest is 7.42 in 1850-51. The average seasonal rainfall over a period of many years is approximately 22 inches.

| Next: Chapter 2 • Contents • Previous: Book 2 |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/up_and_down_california/3-1.html