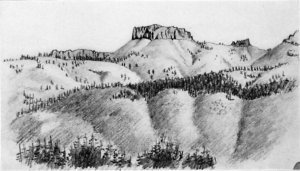

VOLCANIC RIDGES NEAR SILVER MOUNTAIN

From a sketch by J. D. Whitney

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Up & Down Calif. > 1863 Chapter 5 >

| Next: Chapter 6 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 4 |

News from Yale College—Off on Another Journey—Silver Valley—Silver Mountain—A New Mining Town—Mining Fever—Volcanic Lava Caps—Hermit Valley—Winter in the Sierra—Volcano—Tragedy Springs—Silver Lake—Carson Pass—Hope Valley—The Placerville Road—Slippery Ford—Pyramid Peak—Lake Valley—Lake Tahoe—Trout—Mushroom Towns—Dealing in “Feet”—American River Trails.

Volcano, California.

August 13, 1863.

I was to start on a new trip Tuesday, July 27, but Hoffmann was again taken sick—too sick to travel—which gave me much anxiety. I got supplies, then rode up to the Big Trees, fifteen miles, where Professor Whitney was stopping, to consult him. As I have before said, there is an excellent, quiet hotel at Big Trees, and Mrs. Whitney and child are boarding there this summer. The house was full, with a pleasant company. The next day Professor Whitney and I repaired our barometers in preparation for a new trip. He decided upon plans, and I returned to Murphy’s and sent Hoffmann to San Francisco to recruit.

That night I received letters from Professors Brush and Johnson, of Yale College, that took me all aback—an unofficial notice that in all probability next year I shall be invited to a professorship in Yale College—a position I would of all others prize. The college has recently been designated as the recipient of the Morrill Land Fund, donated by Congress to schools for the advancement of agriculture and the useful arts. If the country does not go to pieces Yale will receive some five or six thousand dollars per year from this and new professors will be required to fill the quota. If the place is offered me I shall surely accept it, gladly, and next year will turn my back to the Pacific and my face eastward and homeward once more. It is not yet a certain thing, however, but within the range of possibility.

July 29 I was up at half-past three and in the saddle by four, rode out of town in the early dawn, a lovely quiet morning, and arrived at Big Trees in time for breakfast.

Nora, Professor Whitney’s child, was unwell, so he resolved to stop another day. I, however, went on and camped some fifteen or twenty miles east, killing a tremendous rattlesnake on the way. They grow huge here in the foothills of the Sierra. I took John and our pack mules along. A Doctor Hillebrand goes with us this trip as visitor. He is a resident of Honolulu, Sandwich Islands, where he has lived fourteen years. He is a man of much ability and importance there—a doctor, has charge of botanical and horticultural gardens there, a good botanist.1 He and his family are spending a few months in this state and will return in a few weeks to the Islands. He carried a package of papers with him and collected plants on the trip. We remained there over the next day, and in the meantime Professor Whitney joined us, Nora being better.

July 31 we came on a few miles to Silver Valley, where we stopped—a pretty, grassy, mountain valley. We are already up to a considerable altitude. We examined and climbed a steep volcanic hill lying on the granite near, where volcanic explosions have been reported. We found no traces of such, but had a fine view, commanding a wide extent of country—the snowy Sierra lying along east of us, a wild, rocky, and desolate landscape. The family who live in Silver Valley leave in the fall.

Here let me anticipate. Recent reputed discoveries of silver ore at Silver Mountain, just east of the crest, on the head-waters of the Carson River, near Ebbetts Pass on your maps, has caused much excitement. An old emigrant road over the mountains, via the Big Trees, runs within ten or twelve miles of it, and now, suddenly, travel is pouring over this route. A stage runs part of the way, until the road becomes very rough; then a “saddle train,” with a few pack animals, takes the passengers and their luggage to the promised land. So horses in these mountain valleys all at once become important, and at Silver Valley the stages stop and saddle trains start.

August 1 we came on to near the summit—first over a high ridge, then down a long, rough, and rocky hill to Hermit Valley, on the Mokelumne River, then up again to near the summit, camping at an altitude of over eight thousand feet, where we found grass, water, and wood. We had some fine views on the way and our camp was surrounded by rocky, volcanic pinnacles, picturesque and grand. We had a late supper and good sleep again in the cool air, for the frost settled heavily on our blankets.

August 2 we climbed one of the volcanic pinnacles near camp, over nine thousand feet high, from which we had a grand and very extensive view. We spent the afternoon in camp, and had a bright camp fire in the evening. The night was clear and there was no frost, although the temperature sank to 25° F. August 3 we came on a few miles, crossed the summit, and camped in a canyon about three miles from Silver Mountain. John rode into town, and again we luxuriated in fresh meat. August 4 we went into the town. Professor Whitney examined the mines. I took observations for altitude.

Silver Mountain (town) is a good illustration of a new mining town. We arrive by trail, for the wagon road is left many miles back. As we descend the canyon from the summit, suddenly a bright new town bursts into view. There are perhaps forty houses, all new (but a few weeks old) and as bright as new, fresh lumber, which but a month or two ago was in the trees, can make them. This log shanty has a sign up, “Variety Store”; the next, a board shanty the size of a hogpen, is “Wholesale & Retail Grocery”; that shanty without a window, with a canvas door, has a large sign of “Law Office”; and so on to the end. The best hotel has not yet got up its sign, and the “Restaurant and Lodgings” are without a roof as yet, but shingles are fast being made.

On the south of the town rises the bold, rugged Silver Mountain, over eleven thousand feet altitude; on the north a rugged mountain over ten thousand feet. Over three hundred claims are being “prospected.” “Tunnels” and “drifts” are being run, shafts being sunk, and every few minutes the booming sound of a blast comes on the ear like a distant leisurely bombardment.

Perhaps half a dozen women and children complete that article of population, but there are hundreds of men, all active, busy, scampering like a nest of disturbed ants, as if they must get rich today for tomorrow they might die. One hears nothing but “feet,” “lode,” “indications,” “rich rock,” and similar mining terms. Nearly everyone is, in his belief, in the incipient stages of immense wealth. One excited man says to me, “If we strike it as in Washoe, what a town you soon will see here!” “Yes—if,” I reply. He looks at me in disgust. “Don’t you think it will be?” he asks, as if it were already a sure thing. He is already the proprietor of many “town lots,” now worth nothing except to speculate on, but when the town shall rival San Francisco or Virginia City, will then be unusually valuable. There are town lots and streets, although as yet no wagons. I may say here that it is probably all a “bubble”—but little silver ore has been found at all—in nine-tenths of the “mines” not a particle has been seen—people are digging, hoping to “strike it.” One or two mines may pay, the remaining three hundred will only lose.

It was a relief to meet Mr. Bridges, an old rambler and botanical collector, well known to all botanists.2 For twenty years he rambled in South America and explored the Andes for plants for the gardens and herbariums of Europe. He first sent seeds of the great Amazon water lily to Europe. He spent three months on the island of Juan Fernandez, came to California, and has been supplying the gardens of England and Scotland with seeds, and the herbariums with plants, from this coast, for the last few years. It was a relief to meet him and talk botany; yet, even he is affected—he has dropped botany and is here speculating in mines.

“Mining fever” is a terrible epidemic; when it is really in a community, lucky is the man who is not affected by it. Yet a few become immensely rich.

While visiting the region we kept our camp up the canyon some three miles from town. August 5 Professor Whitney and I climbed the Silver Mountain, a long walk of twelve or fifteen miles, and a very rugged climb. It is over eleven thousand feet high, the highest in the region, and commands a very extensive view. In the north we look into the Carson Valley and even see the mountains of Washoe; in the west is the summit of the Sierra Nevada, the volcanic crests here worn into fantastic outlines; on the southeast are the mountains near Mono Lake and about Aurora; and in the east chain after chain, extending far beyond the state line into the territories. I collected some fine alpine plants and, curious enough, among the stones on the top are myriads of red bugs—beetles—red and brilliant—a pint could easily be collected. We have seen them on many of the peaks, even on Mount Dana, at over thirteen thousand feet.

We got back to camp tired enough, but a hearty supper and sound sleep brought us out all straight again. August 6 we returned again to town and further examined the mines. From Scandinavian Canyon we had some views of the peak of Silver Mountain that are truly grand.

We had spent all the time we had to spare, so August 7 we came up and camped at a little lake at the summit, to examine the pass. It is a most picturesque spot—a small lake of clear water, with green grass and trees around it, and snow banks lying here and there, while on the north of us are a series of volcanic ridges, rough and jagged in outline. Near camp was a most picturesque volcanic cone, its sides made up of strata of basalt, curved and inclined—the whole most beautifully columnar. There are several little lakes in depressions near the summit, all very picturesque, but the feature of the region is the volcanic cap to the mountains—those pinnacles in lava. Were I to see them truly represented on canvas or paper in views of any other country, I should have pronounced the views unnatural and grossly exaggerated. We examined two or three gaps along the summit—a matter of much importance here, for they are building a wagon road through—then finished our work and prepared to return.

August 8 we were off early and started on our return. In about six miles we struck the old emigrant wagon road, where I left the party and went up on the summit to measure the height of that pass, the rest going on. I got back to Hermit Valley that night, and stopped at a house there. The house is a mere cabin, although now a “hotel.” Twelve men slept in the little garret, where there were ten bunks, called “beds.” Two men have wintered here, and in the winter have killed several rare animals—two gluttons, stone martens, silver-gray foxes (so rare that their skins are worth fifty dollars each), large gray wolf, etc.

In winter the climate is truly arctic. A smooth pole in front of the house is marked with black rings and numbers to indicate the depth of snow. The deepest last winter was eighteen feet, but it falls much deeper at a greater elevation in the vicinity. And herein consists the marvel of this alpine region—the immense depth of snow in the winter (on the Placerville Pass the winter of 1861-62 the aggregate depth of snow was fifty feet at an altitude of seven thousand feet) and the little rain in summer, so the snow melts under the clear sky even where fifty or sixty feet fall nearly every winter. Stranger still, trees flourish, of several species, all of large size—there are at least five species of cone-bearing trees that grow where the snow lies abundantly for seven or eight months each year and it freezes nearly every night of the summer; and four of these species grow to trees four feet or more in diameter even under these conditions.

In winter the only way of getting about is on snowshoes, not the great broad Canadian ones that we see sometimes at home, but the Norwegian ones—a strip of light elastic wood, three or four inches wide and seven to ten feet long, slightly turned up at the front end, with an arrangement near the center to fasten it to the foot. With these they go everywhere, no matter how deep the snow is, and down hill they go with frightful velocity. At a race on snowshoes at an upper town last winter the papers announced that the time made by the winner was half a mile in thirty-seven seconds! And many men tell of going a mile in less than two minutes.3

The next day I rode on to Big Trees, a long ride, and overtook the rest of the party there. We remained there one day, then Professor Whitney went to San Francisco on business and sent John and me to go over the Amador road to Lake Bigler. We are on our way there now. My watch needed repairs so I have been detained here at Volcano over today. We had a hot, dusty ride through several mining towns. Why the place is called Volcano I do not know. Bayard Taylor, in his travels, speaks of several craters near, but no one else has ever seen them—they probably exist only in the poet’s imagination.4

There was a terrible accident here yesterday afternoon. The premature explosion of a blast horribly burned two workmen; one died this morning, the other will perhaps follow. The poor fellows were brought into town last night and are horrible objects to look at.

We leave in the morning, cross to Hope Valley and to Lake Bigler; then I don’t know where—perhaps to Plumas and Sierra counties. We shall skim the cream off from the geology of the state this summer, and, as a consequence, of the sight seeing—so I will have less reluctance about leaving it should I come home next summer, as I have intimated a possibility of doing.

Lake Tahoe (or Lake Bigler).

August 23.

August 14 we left Volcano and came on up a new road just built, or rather building, across the mountains near the route of the old emigrant road. Soon after leaving Volcano we struck a table mountain of lava and followed it for two days, up a very gentle grade. Deep valleys lay on both sides, and from many points we had wide views of the foothills and the great valley, all bathed in a blue haze of smoke and dust, like our Indian summer intensified, in which all objects faded in the distance and those on the horizon were shut out entirely.

The next day, still following up the table, we got partially above the sea of dust and haze and at times we could even see the coast ranges. At Tragedy Springs we were up over seven thousand feet. This place took its name from a fearful tragedy. Four men were killed here by the Indians and their bodies burned. Their names are carved on a large tree by the spring, their only monument.5 Here we descended into the valley of Silver Lake, a lovely little sheet of water, very deep and blue, resting in a basin of granite, high, picturesque peaks of volcanic rocks rising on the east. We camped at the foot of the lake, where a large house is going up. Log hotels are going up all along this road, in anticipation of custom when the road shall be finished. We are now up to where we have cold nights—the thermometer sank to 28°.

August 16 we came on nine or ten miles to where we found a little feed. My funds were running so low that I dared not stop over Sunday where we had to buy hay, as we had been obliged to thus far, the cheapest price being four cents per pound.

We rose from Silver Lake and crossed the Carson Spur, a high ridge of stratified volcanic ashes and breccia, capped by hard lava. The South Fork of the American has worn a very deep canyon through this cap down into the granite below. The road winds around the side of this canyon, and here we had the most picturesque scenery of the route. Below us, a thousand feet, dashed the river over granite rocks, the cliffs worn into very fantastic shapes—old castles, towers, pillars, pinnacles—all were there; while above, rugged rocky peaks, volcanic, of fantastic shapes, rose a thousand feet more, fearfully steep, the snow lying in patches here and there. We crossed this spur, behind which lies a pretty lake, called Summit Lake, but “Clear Lake” on your maps. Near this we camped, at an altitude of near eight thousand feet, the snow lying just above us and about us—of course a cool night, temperature down to 26°.

August 17 I climbed alone a high peak south, over 10,500 feet high—a steep, heavy climb. I had to carry barometer, bag with lunch, thermometer, levels, hammer, etc., a canteen, and my botanical box. We have had high winds for several days, and in the morning clouds enveloped the summit of the peak, but they fled before I reached it. The last eight hundred or a thousand feet rise in a steep volcanic mass, so steep as to be only accessible in one place, around cliffs and up steep slopes on the rocks, but there was no serious difficulty or danger. A cold, raw, and fierce wind swept over the summit, but the day was very clear and the view sublime. The peak is just south of Carson Pass, and some twenty to twenty-five miles south of Lake Tahoe (Bigler). The lake was in full view its whole extent—my first sight of it—its waters intensely blue, high, bold mountains rising from its shores. I am higher than the great crest of the Sierra here and hundreds of snowy peaks are in sight. Hope Valley6 lies beneath, green and lovely—high mountains, eleven thousand feet high rising beyond it. Besides Lake Tahoe, there are ten smaller lakes in sight, from two miles long down to mere ponds (which were not counted)—all blue, of clear snow water. It was, indeed, a grand view.

I descended by getting on a steep slope of snow, down which I came a thousand feet in a few minutes where it had taken two hours’ hard labor to get up. I had some time so I returned via the summit of Carson Pass, which was but two miles from camp. The pass is about 8,800 feet high. I got back to camp tired enough, and, of course, slept well after the fatigue of the day, although it froze in the night.

August 18 we crossed the pass and descended into Hope Valley, at the head of Carson Canyon—a beautiful basin, surrounded by high mountains on all sides—itself high, over seven thousand feet. We were hungry enough, and as we were getting dinner some Indians came to camp—two squaws, who had been out digging nuts. The younger, perhaps seventeen or eighteen years old, had a papoose on her back, tied to a willow frame, flat, with a willow flap above to keep the sun off. An old Indian, husband of the elder squaw, soon came up with his boy. He had his bows and arrows and a few squirrels he had shot. They were better looking and much better formed than the Diggers west of the mountains—better features, noses not so flat, mouths not so large, skin lighter—the younger squaw even had well-formed legs and small ankles, both very rare among the Indians west of the mountains. Just before we finished our dinner the old Indian sent the squaws away and gallantly ate up the remains of our dinner, while the squaws looked wistfully back.

We were nearly out of money, but I figured that we could get to Lake Tahoe, with tight calculation, the next afternoon; so I rode up the valley about four miles to visit a copper mine, and, to my great astonishment, found an old acquaintance there, who had been buying into the mine with another partner. He was anxious to get my advice in regard to it, and after I had seen all and given the advice he was only too glad to lend me twenty dollars, which relieved my anxiety immensely.

Now I resolved not to go directly to Lake Tahoe, but to cross the summit and climb Pyramid Peak, which had been in plain view for a long time—a very high and conspicuous point, which had never been measured. So we packed off, crossed a hill, sank into Lake Valley and out of it again, crossed the summit and struck the Placerville road, the grand artery of travel to Washoe. Over it pass the Overland telegraph and the Overland mail. It is stated that five thousand teams are steadily employed in the Washoe trade and other commerce east of the Sierra—not little teams of two horses, but generally of six horses or mules, often as many as eight or ten, carrying loads of three to eight tons, on huge cumbrous wagons. We descended about eight miles and camped at Slippery Ford.

This great road deserves some notice. It cost an immense sum, perhaps near half a million, possibly more. A history of this road would make a good Californian story. First an Indian trail, then an old emigrant road crossed the mountains; when, seeing its importance, the state and two counties, by acts of legislature and appropriations, at a cost of over $100,000 (I think), made a free road over on this general line. But the engineers, honest men, had neither the time nor means given them to do their part of the work well—as a consequence, it was not laid out in the best way. The mines of Washoe were discovered, and an immense tide of travel turned over the road. Men got franchises to “improve” portions of the road and collect tolls for their remuneration. Grades were made easier, bridges built, the road widened at the expense of private companies, who thus got control of the whole route. In other words, the state built a road that these private companies could transport their materials free over to build their toll road. Now, the tolls on a six-mule team and loaded wagon over the road amount to thirty-two dollars, or thirty-six dollars, I am not certain which sum, and it has paid immensely. In some places the profits during a single year would twice pay the expense of building, repairs, and collection of tolls! With such strong inducements men could afford to “lobby” in the legislature and get the franchises. A portion of the road, which is assessed as worth $14,000, last year collected over $75,000 in tolls! It takes a legislature elected for political services to grant such franchises.

The trade to Washoe, being so enormous, other roads are being built across the mountains. The Amador road, described in the first part of this letter, will be to some extent a rival road, but their pass is higher and all the passes south are higher. This pass is less than eight thousand feet.

Clouds of dust arose, filling the air, as we met long trains of ponderous wagons, loaded with merchandise, hay, grain—in fact everything that man or beast uses. We stopped at the Slippery Ford House. Twenty wagons stopped there, driving over a hundred horses or mules—heavy wagons, enormous loads, scarcely any less than three tons. The harness is heavy, often with a steel bow over the hames, in the form of an arch over each horse, and supporting four or five bells, whose chime can be heard at all hours of the day. The wagons drew up on a small level place, the animals were chained to the tongue of the wagon, neighing or braying for their grain. They are well fed, although hay costs four to five cents per pound, and barley accordingly—no oats are raised in this state, barley is fed instead.

We are at an altitude of over six thousand feet, the nights are cold, and the dirty, dusty teamsters sit about the fire in the barroom and tell tales—of how this man carried so many hundredweight with so many horses, a story which the rest disbelieve—tell stories of marvelous mules, and bad roads, and dull drivers, of fights at this bad place, where someone would not turn out, etc.—until nine o’clock, when they crawl under

VOLCANIC RIDGES NEAR SILVER MOUNTAIN From a sketch by J. D. Whitney |

SUMMITS CAPPED WITH LAVA, NEAR THE SONORA ROAD From a sketch by Charles F. Hoffmann |

Pyramid Peak lies about four or five miles north of this point. No one was inclined to accompany me on the climb, all dreading the labor. So the next morning, August 20, I started for the ascent alone. It was very early and cool, frost lying on the grass by the river, but not on the hillside. I climbed a steep hill; in fact, it was all climb, but not so hard as I had expected, for in four hours I was on the summit with barometer, bag with thermometer, hammer, lunch, and botanical box. The day was fine, not a cloud in sight, the air very clear, though of course hazy in the distance. I remained on the top over three hours.

The view is the grandest in this part of the Sierra. On the east, four thousand feet beneath, lies Lake Tahoe, intensely blue; nearer are about a dozen little alpine lakes, of very blue, clear, snow water. Far in the east are the desolate mountains of Nevada Territory, fading into indistinctness in the blue distance. South are the rugged mountains along the crest of the Sierra, far south of Sonora Pass—a hundred peaks spotted with snow. All along the west is the western slope of the Sierra, bathed in blue haze and smoke; and beyond lies the great plain, which for 200 miles of its extent looks like an ill-defined sea of smoke, above which rise the dim outlines of the coast ranges for 150 miles along the horizon, some of them over 150 miles distant. It is one of those views to make a vivid and lasting impression on the mind.

I was back at the house by sunset. All were surprised to find me no more tired, but the fact is, I have never felt in more vigorous health and my weight is reduced to good walking condition. I am now less than 140 pounds.

August 21 we came on up the road, crossed the pass, sank into Lake Valley, and are camped now at the south side of the lake. From the summit there is a fine view of the lake and of Lake Valley, which stretches south from the head. We camped here over yesterday and today, to get barometrical observations and let our animals rest in the good pasture they find here. We are camped in a pretty grove near the Lake House and a few rods from the lake. It is a quiet Sunday, the first we have observed for four weeks.

The lake is the feature of the place. A large log hotel is here, and many pleasure seekers are here, both from California and from Nevada. I was amused at a remark of a teamster who stopped here for a drink—the conversation was between two teamsters who looked at things in a practical light, one a stranger here, the other acquainted:

No. 1. “A good many people here!”

No. 2. “Yes.”

No. 1. “What they all doing?”

No. 2. “Nothing.”

No. 1. “Nothing at all?”

No. 2. “Why, yes—in the city we would call it bumming (California word for loafing), but here they call it pleasure.”

Both take a drink and depart for their more practical and useful avocations.

Lake Tahoe, once called Lake Bigler and as such is on your maps, is the largest sheet of fresh water in the state.7 Recent measurements in connection with the boundary survey make it twenty-three miles long and ten wide, but it has always before passed for much more. It has been recently sounded; its greatest depth is 1,523 feet, and most of it is over 1,000 feet deep. It lies at an altitude of over six thousand feet, while around it rise mountains four thousand feet higher. Its Indian name, Tahoe, was dropped and it was called after Governor Bigler, a Democratic politician. He was once of some notoriety here, but since he has turned “Secesh” all the Union papers have raised the cry to have his name dropped, and the old Indian name has been revived and will probably prevail.

The purity of its waters, its great depth, its altitude, and the clear sky all combine to give the lake a bright but intensely blue color; it is bluer even than the Mediterranean, and nearly as picturesque as Lake Geneva in Switzerland. Its beautiful waters and the rugged mountains rising around it, spotted with snow which has perhaps lain for centuries, form an enchanting picture. It lacks many of the elements of beauty of the Swiss lakes; it lacks the grassy, green, sloping hills, the white-walled towns, the castles with their stories and histories, the chalets of the herders—in fact, it lacks all the elements that give their peculiar charm to the Swiss scenery—its beauty is its own, is truly Californian.

The lake abounds in the largest trout in the world, a species of speckled trout that often weighs over twenty pounds and sometimes as much as thirty pounds! Smaller trout are abundant in the streams. An Indian brought some into camp. I gave him fifty cents for two, and they made us two good meals and were excellent fish. He had speared them in a stream near. We were eating when he came; when we finished he wanted the remains, which I gave him. Rising satisfied, patting both hands on his stomach, he exclaimed, “Belly goot—coot-bye.” Many of these Indians, like the Chinese, cannot pronounce the letter R, substituting an L.

Camp 142, on the Truckee River.

August 27.

On Monday morning, August 24, we started on. I got funds from Professor Whitney and felt all right again. We kept east three miles, to the southeast corner of the lake, then struck north along the shore, now in Nevada Territory. We kept near the shore all day, often crossing ridges where rocky points jut out into the water. We camped at a pretty spot on the shore, the lake in front, and high granite ridges rising behind us—had a cold night.

August 25 we came on, turning around the northeast corner of the lake and striking over ridges to the northwest. Beautiful as Lake Tahoe is from the south, it is yet more so from the north—from having a finer background of high, rugged, black mountains, some of them eleven thousand feet high, or near it, their dark sides spotted and streaked with snow. This end will eventually become the most desirable spot for persons in pursuit of pleasure.

We struck over a ridge, came to the lake again at its north end, then left it entirely, crossing a high volcanic ridge and sinking into a new mining district which is just starting—a new excitement, and people are pouring in. As we went down a canyon we passed numerous prospecting holes, where more or less search has been made for silver ore. Since the immense wealth of the Washoe mines has been demostrated, people are crazy on the subject of silver.

We passed through the town of Centerville, its streets all staked off among the trees, notices of claims of town lots on trees and stumps and stakes, but as yet the town is not built. One cabin—hut, I should say—with a brush roof, is the sole representative of the mansions that are to be. Three miles below is Elizabethtown, a town of equal pretentions and more actual houses, boasting of two or three. We stopped at the main store, a shanty twelve feet square, made by driving stakes into the ground, siding two sides with split boards, and then covering with brush. Bacon, salt, pepper, tobacco, flour, and more than all, poor whiskey, are kept. The miners have camps—generally some brush to keep off the sun and dew; but as often nothing. Some blankets lying beside the brook, a tin kettle, a tin cup, and a bag of provisions, tell of the home of some adventurous wandering man. We passed the town and camped two miles beyond, in Tim-i-lick Valley. The day had been warm, but the night was cold enough to make it up, the temperature sank to 20° F., twelve degrees below the freezing point.

August 26 our animals eloped in the early morning and it took us until ten o’clock to find them and pack up. In the meantime we were joined by a boy thirteen or fifteen years old, who was coming this way and is with us now. Only such a country as this can produce such boys. He was from Ohio—came here in ‘53—went back alone in ‘58—had his pocket picked twice, but was keen enough to have his money in his boot—came back alone last year—now, with his horse, takes a trip over a hundred miles from home among these mountains.

Well, we struck over the mountains for the Truckee River, to this place, where new mines have “broken out”—at least, a new excitement. We crossed a high volcanic ridge, very rough trail, all the way through an open forest of pines and firs, as one finds everywhere here, and camped on the river about Knoxville. Here I have been examining the “indications” today. Six weeks ago, I hear, there were but two miners here; now there are six hundred in this district. A town is laid off, the place boasts of one or two “hotels,” several saloons, a butcher shop, a bakery, clothing stores, hardware and mining tools, etc.—all in about four weeks.

I would give twenty-five dollars for a good photograph of that “street.” A trail runs through it, for as yet a wagon has not visited these parts. The buildings spoken of are not four story brick or granite edifices—not one has a floor, not one has a chair or table, except such as could be made on the spot. This shanty, in the shade of a tree, with roof of brush, has a sign out, “Union Clothing Store.” I dined today at the “Union Hotel”—a part of the roof was covered with canvas, but most of it with bushes—and so on to the end of the chapter. The crowd—only men (neither women nor children are here yet)—are all working or speculating in “feet.”

Let me explain the term “feet” as used here. Suppose a hill has a vein of metal in it; this is called a “lead.” A company “takes up” a claim, of a definite number of “feet” along this vein, and the land 150 to 200 feet each side. The length varies in different districts—the miners decide that themselves—sometimes 1,000 feet, sometimes 1,500, at others 2,000 feet are allowed. In a mine that claims 1,000 feet, a foot sold or bought does not mean any particular foot of that mine, but one one-thousandth of the whole. Thus, the Ophir Mine has 1,500 feet, now worth over $4,000 per foot. One never sees shares quoted in the market, but feet; and feet may be bought at all prices, from a few cents in some to over $5,000 in the Gould & Curry Mine in Washoe. A man speculating in mines is said to be speculating in feet.

There is great excitement here—many think it a second Washoe. Some money will be sunk here before it can be known what the value will be. I have but little faith in it myself. I surely would not invest money in any mine I have seen today, and I have visited eight or nine of the best.

Forest Hill.

Sunday, August 30.

Where I last wrote our camp was on the side of the Truckee River, about six miles below the lake. We had a very comfortable camp. Many small squirrels, a very small species of chipmunk, swarmed about camp—most beautiful little animals. Our boy—his name is Mehafey—rigged up a trap made of our dishpan set on a T-bait, and caught seven of them. By the time we got ready to start they had all got away but one; that one John has brought along—a beautiful little animal, tame already, it rides in his pocket or on his shoulder. I will try and get him to the city if I can. They live only in the high mountains.

August 28 we were up and off early. It rained a little the evening before, but not much. We struck up Squaw Valley, a pretty little grassy valley, then rose the steep ridge to the pass, which is between eight thousand and nine thousand feet. We stopped and lunched there, while I took observations for the altitude of the place. We had a grand view of the mountains south, spotted with snow, and the dim ones east, far in Nevada Territory, and of the western slope fading into blue haze.

We crossed the summit and sank into the canyon of the Middle Fork of the American River, then rose a high hill. We had heard that there was abundant grass on the road, but we found it only partly true. For the rest of the day we followed a volcanic lava ridge—in places only a sharp ridge, with a canyon a thousand feet deep on each side. It was grand, but a very rough trail, in fact, “awful bad,” and, what was worse, no water. We traveled until camp time, then three hours later—for water to camp by. The sun set and the full moon rose long before we struck water. At last, however, we found it—it was nearly nine o’clock before we got our supper. Of course it tasted good after our fatigue and fast. We stopped hungry, thirsty, fatigued, and, as a result, in bad humor; after supper and a big beefsteak we were in fine humor again. The moon was peculiarly bright, the night warm and balmy, just right to sleep well.

August 29 we were off early, but were directed on the wrong trail and it cost us much labor. We followed on down the volcanic table, with a deep canyon on the south, the air very hazy and thick, the foothills becoming lost in the haze in a few miles. We were rapidly getting into a warmer climate. At noon we struck a mining town, Last Chance—hot, dusty in the extreme. Here we found we were on the wrong trail and had to cross three deep canyons. A trail is cut down the steep sides. We descended some 1,500 feet, then rose another volcanic table as high as the first—the top of this canyon, from table to table, is not over three-quarters of a mile to a mile, its depth about 1,500 feet. We crossed this table, passed the little place called Deadwood, and then we had the El Dorado Canyon to cross—still worse—nearly or quite two thousand feet deep, its sides still steeper. Here is a toll trail, very narrow—often a misstep on the narrow way would send the horse and rider, or mule and pack, down hundreds of feet, to swift and certain destruction. It was fearful, yet we had to pay $1.50 for the privilege of passing it. There is a cluster of mining cabins in the canyon. A nugget has just been taken out that weighs seventy-eight ounces (over eight pounds)8 and worth some $1,500.

Well, we came out of that and stopped last night at Michigan Bluffs, a mining town. The town is supported by claims in “washed gravels” that form bluffs nearly two thousand feet above the bottom of the canyon, yet stratified by water. Our horses cost us two dollars each for keep over night. I was anxious to get on, so came to Forest Hill this morning, six miles, once more in a wagon road, but hot and dusty—temperature over 90°.

Since writing the above I have received a letter from Professor Whitney calling me to San Francisco immediately. I will start in the morning at three o’clock and mail this there.

Some of you ask about when I am coming home, and if I have the same old trouble about getting money. First question—I don’t know, probably next year. Second question—the same old trouble. The state now owes Professor Whitney (including our unpaid salaries) about $25,000, and in his letter received this afternoon he says he doesn’t know what he is to do unless he gets money within a month; he has borrowed until he cannot raise any more. My salary is now back to the amount of $2,800, or for one year and two months, and I have to borrow for my personal expenses. I am tired of it. We may possibly get some money in September, but most probably not until December.

It is infamous—political hacks get their money more regularly. We must wait, as our bills have less “political significance,” as the comptroller calls it.

NOTES

1. William Hillebrand was born at Nieheim, Westphalia, 1821. After studying at Göttingen, Heidelberg, and Berlin, he practiced medicine for a time. On account of his health he sought other climates, visiting Australia, the Philippines, and California before settling in the Hawaiian Islands. During a residence of twenty years in Honolulu he made exhaustive studies and collections of Hawaiian flora. He was the private physician of King Kamehameha V and a member of the Privy Council. In 1871 he left Hawaii and resided in Germany, Switzerland, Madeira, and Teneriffe. He died about 1888 (Preface to Hillebrand, Flora of the Hawaiian Islands [1888]).

2. “Thomas Bridges came to California in 1856, and for the next nine years collected on the coast, much of the time in this State, his collections going mostly to Europe. After his death, in 1865, his wife presented the California collections then on hand to the National Herbarium at Washington. They were distributed by Dr. Torrey” (”Geological Survey of California,” Botany, II [1880], 558). A handsome flower, Pentstemon bridgesii, named for him, is found in the Yosemite region. A variety of lupine, also, bears his name.

3. In Overland Monthly (October, 1886), Dan De Quille tells the story of “Snowshoe Thompson,” who for many years carried the mail across the Sierra on Norwegian snowshoes (skis).

4. Bayard Taylor, Eldorado, or Adventures in the Path of Empire (1850), chap. xxiii.

5. The story of Tragedy Springs is told in Serg. Daniel Tyler, A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War, 1846-1847 (1881), p. 337. A party of the Mormon Battalion, returning from southern California to Utah by way of the San Joaquin Valley in the summer of 1848, sent scouts ahead to find a way across the Sierra. About the middle of July the main party, about thirty-seven in number, advanced into the mountains. Because of the rarity of the book, the incident is here quoted in full:

“Some four or five miles took them to what they named Tragedy Springs. After turning out their stock and gathering around the spring to quench their thirst, some one picked up a blood-stained arrow, and after a little search other bloody arrows were also found, and near the spring the remains of a camp fire, and a place where two men had slept together and one alone. Blood on rocks was also discovered, and a leather purse with gold dust in it was picked up and recognized as having belonged to Brother Daniel Allen. The worst fears of the company: that the three missing pioneers had been murdered, were soon confirmed. A short distance from the spring was found a place about eight feet square, where the earth had lately been removed, and upon digging therein they found the dead bodies of their beloved brothers, Browett, Allen and Cox, who left them twenty days previously. These brethren had been surprised and killed by Indians. Their bodies were stripped naked, terribly mutilated and all buried in one shallow grave.

“The company buried them again, and built over their grave a large pile of rock, in a square form, as a monument to mark their last resting place, and shield them from the wolves. They also cut upon a large pine tree near by their names, ages, manner of death, etc. Hence the name of the springs.”

6. Hope Valley was named by the Mormon party after crossing the Sierra from Tragedy Springs, “the spirits of the explorers who first discovered it reviving when they arrived in sight of it” (ibid., p. 239). Frémont had passed this way in February, 1844.

7. Lake Tahoe was discovered in 1844 by Frémont, who called it first Mountain Lake, later Lake Bonpland. In the early fifties it was given the name Lake Bigler, for John Bigler, Governor of California (1852-58). In 1862 the name Tahoe, said to mean “big water” or “water in a high place,” was proposed and soon became generally adopted. An attempt to revive “Bigler” was made in 1870, when the California State Legislature passed “An act to legalize the name of Lake Bigler” (California Statutes 1869-70, chap. lviii, p. 64). This act has never been repealed.

8. This should be six pounds, six ounces (troy weight).

| Next: Chapter 6 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 4 |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/up_and_down_california/4-5.html