CROSSING THE SIERRA NEVADA BY THE PLACERVILLE—CARSON ROUTE

From a drawing by Edward Vischer

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Up & Down Calif. > 1864 Chapter 5 >

| Next: Itinerary • Contents • Previous: Chapter 4 |

Steamboat Springs—The Patio Process—Election Day at Virginia City—Truckee River and Donner Pass—A Moonlight Ride—Goodbye to San Francisco—Voyage to Central America—Volcano Pecaya—Nicaragua—The Lake—San Juan River—Steamer Golden Rule—New York—Home

Enfield Center, New York.

December 22, 1864.

I left my journal incomplete. The last number was written in Virginia City, Nevada, and I intended to write more on the steamer on the way home, but neglected it. Now, although home, I will finish my Californian journal that you may know the rest of the story and to make the journal more complete.

In my last letter I told something about the mines at and near Virginia City. One day I rode out to see the Steamboat Springs with Professor Silliman and Baron von Richthofen. These are very extensive hot springs about ten miles northwest of Virginia City. They lie in a valley about two thousand feet below the city and extend along for about a mile and a quarter. Near the Steamboat Meadow there is a wide valley, and at the foot of one side hill are the springs. Many are of water, of course, but the majority are merely steam jets. Nature’s chemistry has been going on here on a grand scale. The hot water contains silica dissolved, which is precipitated as the water cools. This has made a hill over a mile long, and in places two or three hundred feet high. Steam issues from thousands of vents, hissing, puffing, spouting—it can be seen for miles. Some of the springs are intermittent in their activity. One I timed and found that the water would sink in the basin and then rise and overflow again at intervals of about five minutes. They are very extensive, and there are signs that many others have existed in the region at some former times. Much of the country is volcanic.

Monday, November 7, I went home with a Mr. Hill, who lives near Dayton, on the Carson River about ten miles from Virginia City. He works tailings from the mills by the patio process. Many of these tailings are very rich in silver still, for the mills fail to get it all out. Often over a hundred dollars per ton is left. The patio process is Mexican, and this is probably the only place in the United States where it is used. Great wooden floors are laid on the ground, tight, with a rim around, like a dish or tub, forty-five feet in diameter and fifteen inches deep. Into this are put the tailings—a mixture of sand and sticky mud—to the depth of ten or twelve inches. Some salt, sulphate of copper, and quicksilver are sprinkled in, and after the mass is moistened it is tramped with horses. Every day for a short time horses are driven round and round in this mud, for a month or more, when the process is finished. More of the chemicals are added from time to time as the process goes on. When finished, the mass is washed in sluices, the mud carried away by water and the amalgam left. This process, which looks so rude, extracts the silver cleaner than any of the so-called refined and perfected processes. This man is getting rich working over tailings, which he must buy at the mills. The horses are poor old “plugs,” picked up wherever he can get them cheapest. They get very poor and look comical enough, stained by the sulphate of copper—white horses, with green legs and tails, and blue and yellow spots over them, streaked and speckled and miserably poor.

The next day we returned to Virginia City, arriving about noon. It was election day. I had no vote, of course. One should see the elective franchise exercised in such a new place to have a realizing sense of the free and enlightened voters exercising their rights. Men argued but little, but opinions were freely

CROSSING THE SIERRA NEVADA BY THE PLACERVILLE—CARSON ROUTE From a drawing by Edward Vischer |

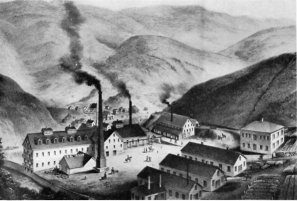

GOULD & CURRY SILVER MINING COMPANY’S MILL VIRGINIA CITY, NEVADA From a lithograph published in 1864 |

I intended to leave the next day, but found the stages filled, so I had to wait over. I took a stroll over the hills a few miles, looking at the rocks and geology of the country.

On November 10 I bade goodbye to my friends at Virginia City and got upon the stage at noon for California again. I rode on the box with the driver, so I had a good chance to see the country. We crossed the Truckee River and then ascended the grand Sierra. We went by the Truckee Pass, where the Pacific Railroad is to cross, according to present hopes. We passed by Donner Lake, a beautiful sheet of water three miles long, the scene of the fearful tragedy that overtook the Donner party at “Starvation Camp” a few years ago. Here we took supper; then again on the stage and over the pass.

It is the grandest of the wagon road passes that I have yet seen. The moon was at its full, and as a little snow lay around and as the naked granite rocks are so very light colored, we could see almost as well as by day. The road winds up the rocky height through a scene of unmitigated rocky desolation—great bare crags, with here and there a tree or bush struggling for existence in the corners and crevices—all else naked rock and snow. How a railroad is to be got through and over this pass is not easy to see. It will take much money.

The night was cold as well as clear. After crossing the summit we were soon in the grand forests of the western slope. We had a jolly set on the stage, that is on the top, and we awoke the echoes of the mountains with our songs. I slept but very little that night. We passed through Dutch Flat, now so familiar to every Californian because of its name in connection with the railroad, and finally reached the railroad soon after daylight, near Auburn, and were in Sacramento in time for breakfast. I stopped there until the afternoon and then went to San Francisco. During my stop I called on the comptroller and got the cheering news that we would probably be paid up in January next.

It was a mild lovely afternoon as we sailed down the muddy Sacramento. The hazy air shut out all views of the Sierra. Nothing but the level banks of the river was in sight, yet at times even these were picturesque, with their festoons of vines and the gray willows hanging over the lazy water.

The next two days I was busy enough. I finished packing up and called on friends to bid them goodbye. I had made many warm friends in that city, and I parted with many, probably never more to see them in life. I spent the last evening, Sunday, at my boarding house, where I felt almost at home.

Monday morning, November 14, I was up early and off for the steamer. I bade goodbye to dear Hoffmann. He was out of bed, but could not walk yet. He wept like a child when I left, and I felt like parting from a brother. For over three years we had been together almost all the time—in winter in the office, and during summer in the field.

Several of my friends came down to see me off. We were off at half-past ten. It was a dull, foggy morning, and the hills of Oakland were dim. We stopped out in the stream while the passengers were marshaled and a boatload sent ashore—those who had forgotten to provide themselves with tickets. It was “opposition day” and we were on the opposition steamer, America. The steerage was full—over 100 had been turned away, and 650 were crowded in there. The second cabin was crowded, but the first cabin was not full. I had a stateroom to myself, on deck, one of the pleasantest on the boat, thanks to the agent at San Francisco, whom I had once met in Yosemite Valley and who had thus kindly remembered our meeting.

We soon settled down to the monotony of ocean life. We got acquainted with genial or congenial friends, we gazed off on the ocean, we ate, we read, we smoked, we slept. Occasional glimpses of the rugged coast of California, a school of porpoises, a whale, or the miseries of some seasick passenger as he hung over the gunwale of the ship and contemplated the mighty deep, were our only excitements. We were not yet acquainted and did not feel at home.

As we ran down along the coast a change came over the spirit of the scene. We left fogs behind and entered the sunny climate and balmy air of the Mexican coast. Bright skies and blue sea came on, the days waxed longer and the nights shorter. We passed Cape San Lucas on the nineteenth, scarcely half a mile from the forbidding shore, and the next day crossed the Gulf of California. We had an unusually cool passage—the captain says the coolest he has ever made on this route. On the twenty-first we passed a steamer of the French blockading fleet off Acapulco, which some thought a pirate of the Rebel persuasion until we were fairly up to her.

Along the coast of Central America the grand volcanic cones rose against the sky, some in sharp outline, others with clouds curling over them, but all very grand. One morning a fellow passenger awoke me before five o’clock to see a grand sight, the volcano of Pecaya in eruption. It was forty or fifty miles distant, but the night was clear. A pillar of clear, white smoke or steam curled up into the blue sky from the sharp cone, and a great stream of lava ran down, forming a broad, glowing belt down the side of the mountain. At times great volumes of steam and smoke would roll up, while along the line of the lava stream steam curled up here and there, perhaps where the hot lava found moist ground or water. It was less distinct after day broke, but for nearly a hundred miles we could see the smoke rising from it. This volcano is in the southern part of Guatemala.

Sunday, November 27, we ran down close to the land all the morning and before noon anchored in the little harbor of San Juan del Sur, where we landed in launches.

The transit company was on hand with wagons, horses, and mules to transport the passengers to Virgin Bay, on Lake Nicaragua, twelve miles distant. Our little group of six or eight, called by envious passengers “The Committee,” had taken means to get good animals, ordered for half-past one. Captain Merry of the America was to go with us. For five tedious hours we waited in the heat for those animals. We could not go out for fear they would come, for they were often promised in a few minutes. Well, the animals did not come until night, and we found out that we could leave the next morning and reach the lake steamer in time, so we went back on board the America and spent the night.

First, however, we looked around the village. Houses were scattered here and there among the trees, without any order, and of very primitive construction. The furniture is very scanty, and the people live very simply. They are vastly superior to the natives of the Isthmus of Panama in looks, and have much less negro blood. They appear to be the genuine descendants of the aboriginal natives, with but little foreign blood intermingled. The women appear finer than the men, and many of them struck me as decidedly beautiful—too dark for brunettes, yet not black—complexions rich and soft, lips well set, magnificent teeth, large and liquid black or hazel eyes—hair long and flowing, fine as silk and gently wavy or straight, which they had put up in the neatest manner—fine forms, which their very thin dresses showed off to good advantage. The climate is such that dress is worn merely as a matter of taste and decency rather than for warmth. That of the men consists of pants and shirt, that of the women consists of a very thin skirt extending to the ankles, and a jacket or sack which hangs over the skirt. They go bareheaded, or with a gay, light shawl thrown over the head. Such are the natives of Nicaragua as I saw them in three towns—San Juan del Sur, Virgin City, and Castillo Viejo.

We slept on the ship that night and were off at dawn for Virgin City. Our party was about a dozen—all the rest had crossed the day before or in the night. We presented an imposing appearance. Ahead was your humble servant on a poor mule, who went better than he looked, his nose (the mule’s not the writer’s) begirt with a hackamore which answered as a bridle, and with curious native saddle in which it was hard to see which predominated, wood, rawhide, or straw—a small American flag fastened on his umbrella floated to the morning breeze. Next came Higby, M. C. from California, a capital fellow; next Captain Roberts, a millionaire from California, also a capital fellow; then Captain Merry of the America. Not the least of the party was Ossian E. Dodge, the concert singer, on a poor horse, a great linen coat fluttering, and a bunch of bananas hung to his saddle, which every few rods left one of their number along the road, so he had scarcely any when he got through.

As we crossed the summit Lake Nicaragua came in view, with its deep, blue waters, its rich shores, and its sharp volcanic cones. We arrived at Virgin City in due time. All the passengers were there, and soon the whole of the baggage had arrived. Baggage is hauled over on carts of the most primitive character—the wheels cut from some big trees, no iron used in their construction, only wood and rawhide—four or six oxen hitched to each by yokes that are strapped before the horns.

At noon we were on the lake steamer City of Leon and the minute the last baggage was on board the boat left the wharf, leaving behind thirteen passengers who had been tardy without excuse—the brutal captain would not even send a boat for them. They shouted wildly on the wharf, scarcely thirty feet from us, but all in vain—they were left at that miserable hole for a whole month, all because of the bullheaded stubbornness of Captain Hart of that steamer. The passengers will have no redress, of course, as it was owing mostly to their own carelessness that they were left. Nearly a thousand of us were crowded on that boat, with bad food and but little of it, and berths for about one hundred.

The lake is about a hundred miles long by twenty or twenty-five wide. In the middle, on an island, are two volcanic cones rising from the water to 4,200 and 5,100 feet, respectively—perfectly sharp and regular. We ran down the lake about fifty miles before we entered the River San Juan. Toward the foot of the lake are many small rocky islands, all covered with rich vegetation. We continued down the river some miles after dark until we got to where the water was too shallow for our boat, when we came to a little river steamer. The boats remained here until morning, and the passengers distributed themselves over the two boats and thus diminished the crowd. There were no berths. Luckily I had bought a hammock of a virgin at Virgin City, and more luckily Captain Merry had had a nice lunch put up for us. We opened it at midnight after a fast of twenty-one hours.

At daylight the rest of the passengers were transferred and we went down the river two miles to some rapids. Here we got off and walked around the rapids, some two or three hundred yards—a railroad with rude horse cars carries the baggage. This is at Castillo and Castillo Viejo, two little towns, with a curious mud fort on the hill just above. This was Tuesday, November 29. The rainy season had not finished, and it rained part of the day—hot, steamy showers. The shallow river, the rich and varied shades of green in the forests, the strange forms and species, the gorgeous colors of flowers, the great masses of rich foliage and festoons of vines, screaming parrots and paroquets and other birds of brilliant plumage, monkeys jumping about on the trees and chattering at the steamer as it passed, lazy alligators lying alongshore and tumbling into the water at shots from pistols, scaly iguanas almost as brilliantly colored as the flowers themselves—all these sights and sounds, not to mention the smells, told us we were in another clime from that of our homes. It brought back all the old stories I had ever read of tropical countries, of Spanish adventure, and the romance of Central America.

We got into the harbor at Greytown, or San Juan del Norte, after dark. Some of the passengers went ashore, but I stayed on board. I bought some bananas and bread for supper and got a good night’s rest in my hammock. The bar has filled up so of late that the steamer cannot get into the harbor—it must anchor outside. We were transferred to a tug the next morning and were carried out. The tug rolled heavily, so did the steamship, and it began to rain hard. It was found impossible to transfer passengers and baggage directly to the ship, so we anchored and were put aboard with small boats.

We were now on the steamer Golden Rule, Captain Babcock—a fine steamer and fine captain. We lay there two days, then started. We were getting on in very good season, when the engine broke—something about the eccentric—so the engine had to be worked by hand. This delayed us. Then the last three days we had heavy gales from the north—very heavy the last day, Saturday, December 10. The ship rolled terribly—the wheelhouses would go under on both sides. We got up to Sandy Hook after dark, and failing to get a pilot, ran in without one. The moon was bright and the hills on all sides were white with snow. Three days before thin shirts and linen coats were in demand, now overcoats and furs.

Some of the passengers went ashore that night, others the next morning—I among the rest. Monday I ran about the city, delivered some packages, saw some men on business, and left for home that night, arriving at Ithaca the next morning at eight o’clock. I footed it home and arrived at 11 A.M. on Tuesday, December 13, 1864.

All looks familiar—some few changes, but Providence has been kind. We are all together again, all in good health. It seems as if I had not been away as we gather about the fire of a cold, wintry evening. All of us look a little older in the face, but hearts and affections are as young as when I left to ramble so far from home. We have snow and cold weather, a winter’s landscape and a winter fireside, where we mutually have many things to tell.

And here let my long letters cease. It is by no means probable that I shall write so long a series again, or at least under such exciting circumstance or amid such interesting scenery. I trust you have had as much pleasure in reading as I have in writing them.

| Next: Itinerary • Contents • Previous: Chapter 4 |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/up_and_down_california/5-5.html