| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Indians > Indian Legends >

Next: References • Contents • Previous: Ceremonies & Customs

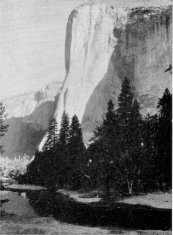

Living close to nature as did the Indians, In constant close relationship with animals, plants, and other natural features, it is easy to understand how their religion, their superstitions, and their legends should center around the great cliffs and spires, the waterfalls, animals, and even the winds which they knew in their daily existence. As is characteristic of primitive peoples without a written alphabet, the legends of the Yosemite Indians were handed down by word of mouth, from generation to generation. It is reasonable to assume that elaborations developed with the passing of time. The three legends which follow tell of the origin of several of the most beautiful features of Yosemite Valley—El Capitan, the massive cliff at the lower end of the valley; the Lost Arrow, a spectacular shaft of rock jutting out from the cliff just to the east of Yosemite Falls; and Half Dome, Royal Arches, Washington Column, and Basket Dome at the upper end of the valley.

|

Long, long ago there lived in the Valley of Ah-wahnee two cub bears. One hot day they slipped away from their mother and went down to the river for a swim. When they came out of the water, they were so tired that they lay down to rest on an immense, flat boulder, and fell fast asleep. While they slumbered, the huge rock began to slowly rise until at length it towered into the blue sky far above the tree-tops, and wooly, white clouds fell over the sleeping cubs like fleecy coverlets.

In vain did the distracted mother bear search for her two cubs, and although she questioned every animal in the valley, not one could give her a clue as to what had happened to them. At last To-tah-kan, the sharp-eyed crane, discovered them still asleep on top of the great rock. Then the mother bear became more anxious than ever lest her cubs should awaken, and feel so frightened upon finding themselves up near the blue sky that they would jump off and be killed.

All the other animals in the valley felt very sorry for the mother bear and promised to help rescue the cubs. Gathering together, each attempted

El Capitan |

to climb the great rock, but it was as slippery as glass, and their feet would not hold. Little field mouse climbed two feet, and became frightened; the rat fell backward and lost hold after three feet; the fox went a bit higher, but it was no use. The larger animals could not do much better, although they tried so hard that to this day one can see the dark scratches of their feet at the base of the rock

When all had given up, along came the tiny measuring worm.

“I believe I can climb up to the top and bring down the cubs,” it courageously announced.

Of course, the other animals all sneered and made sport of this boast from one of the most insignificant of their number, but the measuring worm paid no attention to their insults and immediately began the perilous ascent. “Too-tack, too-tack, To-to-kon-oo-lah,” it chanted, and surely enough its feet clung even to that polished surface. Higher and higher it went, until the animals below began to realize that the measuring worm was not so stupid after all. Midway the great rock flared, and the measuring worm clung at a dizzy height only by its front feet.

Continuing to chant its song, the frightened measuring worm managed to twist its body and to take a zig-zag course, which made the climb a great deal longer, but much safer. Weak and exhausted it at last reached the top of the great rock, and in some miraculous manner awakened the cubs and guided them safely down to their grief-stricken mother. Of course, the whole animal kingdom was delighted and overjoyed with the return of the cubs and the praises of the measuring worm were loudly sung by all. As a token of honor the animals decided to name the great rock “To-to-kon-lah” in honor of the measuring worm.

[Editor’s note: this “legend” “is almost certainly fictitious” according to NPS Ethnologist Craig D. Bates. It was first printed in Hutchings In the Heart of the Sierras (1888) —dea.]

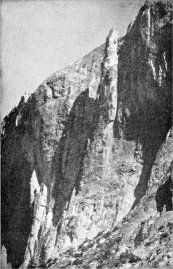

Tee-hee-neh, a beautiful Indian maid, was betrothed to Kos-soo-kah, a young brave, who was fearless and bold with his spear and bow. At dawn on the day before their marriage, Kos-soo-kah made ready with other strong braves to go forth into the mountains to hunt bear, deer, rabbit and grouse for the wedding feast. Before leaving, he slipped away from the other hunters to meet Tee-hee-neh, his bride, who was waiting nearby.

As they parted Kos-soo-kah said, “We go to hunt now, but at the end of the day, I will shoot an arrow from the cliff between Cho-look, the high fall, and Le-hamite, the Canyon of the Arrow-wood, and by the number of feathers you will know what kill has been made.”

Tee-hee-neh happily assisted the Indian women in preparing acorn bread and other food for the marriage celebration until the appointed time when she was to wait at the foot of the high fall for the arrow message from Kos-soo-kah. Hour after hour she waited until gradually the joy she had known was replaced

Lost Arrow |

“Kos-soo-kah,” she called again and again, but the only answer was the faint echoing of her own voice. Breathless, frightened, and her heart heavy with a dreaded fear that Kossoo-kah had met with harm, she at last reached the summit. Seeing footprints in the direction of the cliff, she moved toward the edge in bewildered alarm, not for her own safety, but for what she might behold. As she leaned over and looked down, she gave a piercing cry of despair, for in the starlight she beheld the still form of her loved one lying on a ledge below with the spent bow in his hand. She now remembered that at the hour of sunset while she stood waiting for Kos-soo-kah’s arrow to fall she had heard the distant, thunder-like rumble of a rock slide. Her despair was almost overwhelming as she realized that while her faithful Kos-soo-kah stood on the edge of the cliff to draw his bow, he had been caught in the unexpected slide of earth that had hurled him to his doom.

A faint hope stirred in Tee-hee-neh’s heart. Perhaps Kos-soo-kah was still alive. To summon assistance as quickly as possible, she frantically collected cones and dead limbs to light a signal fire for urgent help. Although numbed with grief, she kept the fire bright and high for several hours before men from the valley and other braves who were returning from the hunt in the high country were able to reach her. Quickly, the braves made a pole from lengths of tamarack and fastened them securely with thongs of hide from the deer that had been killed for the marriage feast. Although exhausted, Tee-hee-neh was the first to descend to the ledge where Kos-soo-kah lay. As she knelt beside him and listened far breath, her own heartbeat almost stopped, for the brave Kos-soo-kah was cold and still. Without a murmur, she motioned for the men above to lift her.

Tee-hee-neh’s wedding day had dawned when the braves were at last successful in raising the body of Kos-soo-kah to the top of the cliff where the others waited. As his lifeless form was placed gently on the ground, Tee-hee-neh knelt beside him, and with tears streaming down her cheeks she repeated his name over and over, as though by doing so she could call him back to her. Suddenly she fell forward on her dear one’s breast, and her spirit too departed to join that of Kos-soo-kah in the land that knows no partings.

With great wailing and mourning the two lovers and all their belongings were placed for cremation on the funeral pyre in accordance with the burial custom. In Kos-soo-kah’s hand was the fatal bow, but the arrow had been lost forever. In its stead the spirits lodged a pointed column of rock in the cliff between Cho-look, the high fall, and Le-ham-ite, the canyon of Arrow-wood in memory of the faithful Kos-soo-kah who met his death in keeping a promise to Tee-hee-neh. Ever since this rock has been known as Hum-moo, the Lost Arrow.

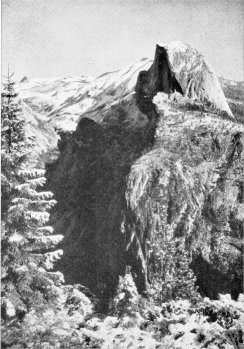

Many, many generations ago, long before the Gods had completed the fashioning of the magnificent cliffs in the Valley of Ahwahnee, there dwelt far off in arid plains an Indian woman by the name of Tis-sa-ack and her husband Nangas. Learning from other Indians of the beautiful and fertile Valley of Ahwahnee, they decided to go there and make it their dwelling place. Their journey led them over rugged terrain, steep canyons and through dense forests. Tis-sa-ack carried on her back a heavy burden basket containing acorns and other articles, as well as a papoose carrier, or hickey. Nangas followed at a short distance carrying his bow, arrow and a rude staff.

After days and days of weary traveling, they at last entered the beautiful Valley of Ahwahnee. Nangas being tired, hungry and very thirsty, lost his temper, and without good reason he struck Tis-sa-ack a sharp blow across the shoulders with his staff. Since it was contrary to custom for an Indian to mistreat his wife, Tis-sa-ack became terrified and ran eastward from her husband.

As she went, the Gods looking down, caused the path she took to become the course of a stream, and the acorns that dropped from her burden basket to spring up into stalwart oaks. At length Tis-sa-ack reached Mirror Lake, and so great was her thirst that she drank every drop of the cool, quiet water.

When Nangas caught up with Tis-sa-ack, and saw that there was no water left to quench his thirst, his anger knew no bounds, and again he struck her with his staff. Tis-sa-ack again ran from him, but he pursued her and continued to beat her. Looking down on them, the Gods were sorely displeased.

“Tis-sa-ack and Nangas have broken the spell of peace,” they said. “Let us transform them into cliffs of granite that face each other, so that they will be forever parted.”

Tis-sa-ack as she fled tossed aside the heavy burden basket to enable her to run faster, and landing upside down it immediately became Basket Dome; next she threw the papoose carrier, or hickey, to the north wall of the canyon, and it became Royal Arches. Nangas was then changed into Washington Column, and Tis-sa-ack into Half Dome. The dark streaks that still mar the face of this stupendous cliff represent the tears that Tis-sa-ack shed as she ran from her angry husband.

Half Dome from Glacier Point |

Next: References • Contents • Previous: Ceremonies & Customs

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_indians/legends.html