[click to enlarge]

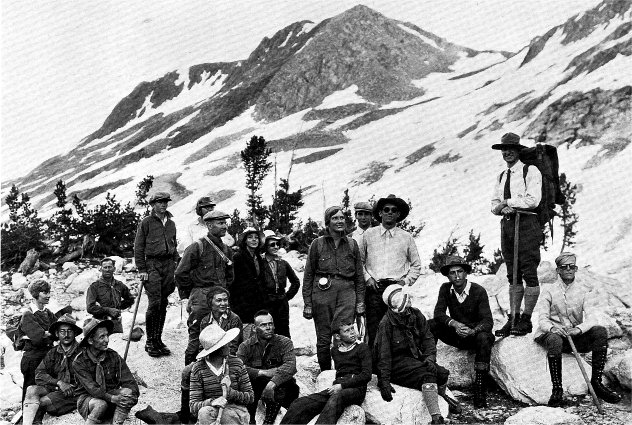

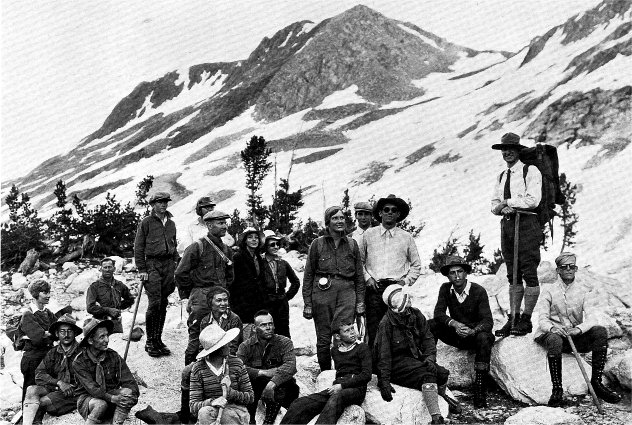

Dr. Carl W. Sharsmith (upper right) with a group on the Conness Glacier in July, 1932.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > YNN > YNN 46(2) > Dr. Carl W. ‘Zeke’ Sharsmith >

Contents • Previous: Impromptu Interpretive Walks

[click to enlarge] Dr. Carl W. Sharsmith (upper right) with a group on the Conness Glacier in July, 1932. |

Will Neely, February 22, 1977

“Go tell the District Ranger

Go tell the District Ranger

Go tell the District Ranger

That Carl and Will are dead.

They died on the glacier

They died on the glacier

They died on the glacier

The campers done ’em in”

[Spontaneous song by the Tuolumne hikers after a trip to the Lyell Glacier, 1954 to the tune of “The Old Gray Goose is Dead”.]

What follows is neither a tribute nor eulogy to Dr. Carl Sharsmith. He is very much alive; he is near-legendary in Yosemite, and there are many who want to write things about him, much of it true.

What I write is true, too, but he is such a long way from being legendary, completely, that I may beat him to the finish line: that will force him to say something nice about me, and I’ve seen what agonies he suffers when he has to write something.

He can talk all day long, smoke 67 pipefulls of Union Leader tobacco, sing old ballads until everyone has gone to sleep, talk at campfires about metamorphic rocks of the Sierra until only the first devoted row is still attendant, the rest having slipped off into the freezing darkness and their beds.

But writing is an agony.

He can lead seminars in Alpine Botany at 12,000 feet and get complaints from burly hikers and lissome school teachers . . . “we just can’t keep up with him!” That is not close to being legendary.

He hates to write; it is easier for him to digest beans than digest thoughts to go on paper. We were asked to contribute each summer an article for Yosemite Nature Notes; it was publish or perish. Carl would pace up and down, forward and back, filling the air with Union Leader smoke . . . swearing and cussing.

Writing comes easier to me, perhaps because I don’t live on beans.

It was our first summer together, my new wife and I. 1949. We came skipping down from the summit of Mt. Lyell, sliding on the glacial ice, sliding because we wore moccasins. At the top we had picked a bunch of pretty blue flowers. Below, on the glacier, we could see a long string of hikers coming up, Dr. Sharsmith in the lead, ice axe in hand. It was the Yosemite Field School of Natural History.

What could he say to these two, glissading down the ice in moccasins and proudly showing him the pretty blue flowers? The Field School gasped. Carl told us they were Polemoniums, Sky Pilots, that they we rare and should not be picked.

A week later I saw him at his cabin at Tuolumne. He was fixing a tire for his 1935 Ford Roadster (more about this car later).

“Dr. Sharsmith, I am interested in Alpine Ecology”.

“Hmmph!”

“And I would like to know how to become a ranger here.”

“Do you know they charge a whole dollar to fix a tire?”

“I realize now what it was to pick Polemoniums up there on Mt. Lyell.” I was not interested in the price of fixing tires.

He pointed his finger at my chest. “A whole dollar!”

At that time, Carl was the only naturalist at Tuolumne Meadows. I knew little about his Swiss frugality, or that he had jars of turkey fat stored away in the cabin loft . . . turkey fat from Thanksgiving dinners gone by . . . to be used some day, even if the fat became petroleum. I tried to talk about becoming a ranger. At times Carl cannot be derailed; the finger tapped my chest, “a whole dollar, just to fix a tire, why, back in 1930 . . .”

I was assigned to Tuolumne Meadows in 1952 because I proved myself incapable of standing behind the information desk all day long. I was supposed to give the geology talk at the Valley Museum twice a day, all of us grouped around the plaster relief models of the Valley. I took the group out to see the real thing instead of the plaster. Chief Park Naturalist Donald McHenry caught me returning with my 75 visitors and called me into his office. “Will”, he said, “it looks like you are an incorrigible field man.” The next summer I was sent to Tuolumne.

I learned more about Carl that summer. We had to cut our own firewood for the campfire programs. A huge lodgepole pine had fallen near our tents. We took a two-man, 7 foot saw and started. I could not see Carl on the other side of the log, but I began to think that sawing is mighty strenuous work until I saw a little wisp of tobacco smoke coming up from the other side. Carl was laughing. “I’ve been getting a free ride on this saw for the last half hour” he said, “you don’t need to push back, let me do that!” He told me an old logger’s saying, “I don’t mind you riding the saw, but don’t drag your feet.” He had one finger curled around the saw handle. I was doing the work. That has been our history ever since: I do the work and Carl gets the credit.

Carl is well-known for his Swiss frugality. It was an unusual event when he invited me for dinner. I admit I sat in his tent determined, until he had to invite me out of courtesy. Afterward, we quietly smoked our pipes and looked at the alpen glow on Mt. Dana; then I went back to my tent to eat enough more to keep me alive.

Carl is not frowsy. He is neat and clean; his tent is a model of sparse, Swiss orderliness. He comes up to Tuolumne each summer in his 1935 Ford V8 Roadster. It used to be a sort of grey-green color and by the end of the summer it became covered with the fine driftings of Yosemite dust . . . “ground-up scenery”, he calls it, and a layer of pine pollen. We named it the “Talus Boulder”. Then, some time in the last couple of decades, he had it painted forest green, and to protect the finish until the next Ice Age, he covers it with canvas, firing it up about three times a summer, the first time on August 1st, a Swiss national holiday.

Inside his tent is his old Coleman stove, the brass tank gleaming. Next to it his cutlery, his “eatin’ irons,” and guests, if they like salt pork, onions and beans, must bring their own tools. A frying pan hangs near the stove, its lid looks like a battered shield from the Trojan Wars, a sauce pan that probably was dredged up from a 49’er gold camp, spatula, a good French knife, and a shelf with a few cans of beets, chili sauce, and old Union Leader tobacco cans full of staples like sugar, flour, fat, tobacco.

We had a competition to determine which of us could live on the least . . . the least money on food per day . . . Carl won, at 33¢. I had soared to 55¢ because I had indulged in an occasional hamburger. I found out later that he was frequently invited out. He has a way of putting down three helpings of food when others are on firsts.

No, he is not frowsy; he neatly patches his pants, sews his boots together, mends his shirts and looks presentable, in his own peculiar way. Some people always look neat no matter what they wear, others look frowsy and I am one of those. When I first wore my spanking brand-new uniform, McHenry took me aside and said in a fatherly way, “Will, you ought to spruce up a bit, you look shabby.” But when Carl was presented the Secretary of Interior’s award for Meritorious Service, Doug Hubbard, then Park Naturalist, had to lend him his belt because Carl’s, although regulation, dated to the thirties and looked like something off the harness of a pack mule. But he somehow never looks shabby.

Carl can be inflating or deflating. Some inconspicuous lichen becomes magic under his hand-lens, or the excitement of a rare plant, such as his precious Saxifraga debilis found underneath an overhanging rock on Mt. Dana . . . one of the most miserable and weak-minded, scrawny-limbed alpine plants I’ve ever seen, yet after a half-hour in the cold wind looking at it, hearing about it, we would be near-ready to give our lives for its preservation.

Crepis nana grows unhappily on the debris of the terminal moraine of the Dana Glacier where few other plants care to live. Carl talked about its rarity with wonderment and we came away inspired. A few weeks later I found it on the nearby tailings of the May Lundy mine and eagerly brought a carefully pressed specimen to his tent; he looked up from the stove and said, “Yes, I suspected it might be growing there” and went on frying onions as though Crepis nana were as common as Tuolumne mosquitoes. Deflated, yes, but when I show Crepis to the public on a Dana Glacier hike, the old magic comes back.

When I found, between Dana and Gibbs, a peculiar white flower, I brought it back; Dr. Carl pointed his spatula at me. “This is cerastium Beeringianum, and if you were a botanist (I cringed because I thought I was) you would call this a red-letter day of discovery!” I was inflated. You never know how he will be on a hike or walk. Much of his mood depends upon what he has been reading. For two weeks, he had on an Irish brogue because he had been remembering his logging camp days. Then he becomes the “Old Timer” and you can’t get any serious information out of him, just remembrances and he scratches the back of his neck, pushes up his hat and says “well, back in ’04 . . .” and one hears about mules and old Zeke.

I know when he has been reading about Indians; come up with a question and he solemnly points a finger at you, taps your chest, “You pale face don’t know nothin’. What dat grass you say? What dat grass. Don’t you know? De Indian woman, she takum dat grass, it strong and she makum basket wid it. You see dem fibers? You try to break ‘um. Indian know . . .”

After his trip to Switzerland, Carl came back infected with that throat disease that is called the Swiss language. No question in his tent was answered until we had to listen to some obscure passage from a Swiss story book. Towards the end of summer of 1976, we learned to be wary, not get trapped with that infernal book; we pussy-footed around his Swiss recitations, got away by excuses such as “my food is burning”, “I have to go on duty now”, or “there is a pressing forest fire, I must attend”, or “excuse me, the mountain is falling down”. The recitation went on and on.

At last, the summer over, and we were packing to go home, Carl placed his chair in the triangle of three tents and read his Swiss book out loud to himself. His voice carries.

When I came home, I studied Swiss and was also infected with that same throat disease. Such is his magic.

Yet he can be patient hour after hour at the information desk, answering the eternal questions of the public, each of the visitors coming away with the inspiration that they have somehow asked the right thing to turn him on. They feel elated with his personal attention when they bring a piece of rock and ask what it is. Carl looks at it professionally with his hand lens as if they had brought a gold nugget. It is really a simple feldspar crystal. He quotes Matthes and says, “Ah, if that rock could talk!” The feldspar soon becomes the whole history of the Sierra.

Only once did he lose his patience . . . It was after the 657th time that day some visitor, after a whole stream of them, had asked “Say, ranger, where can I catch a fish?” The Old-Timer ’04 voice came on, drawlingly, tobacco spittingly, “Wal, if’n I wuz yew . . .”

“Yes?”

“Wal, yew know whar the store is, don’t you?”

“Yes, but . . .”

“Yew jes’ go up to thet store, walk inside to the far wall and yew’ll see all them rows of canned sardines. Catch ’em thar!”

Inspiration, deflation, quiet academic veracity, long-winded mendacity . . . our Dr. Carl.

After a campfire talk where I thought I was pretty good, he said “Will, you’ll never be a scientist. You are the eternal rebel against the tyranny of facts”.

Inspiration? Deflation? Dear Carl, gull-dang his hide.

Contents • Previous: Impromptu Interpretive Walks

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_nature_notes/46/2/carl_sharsmith.html