[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > YNN > YNN 46(2) > Reflections in Tuolumne Meadow >

Next: Rights for Natural Objects • Contents • Previous: Yosemite as a Process

[click to enlarge] |

by Jim Sano

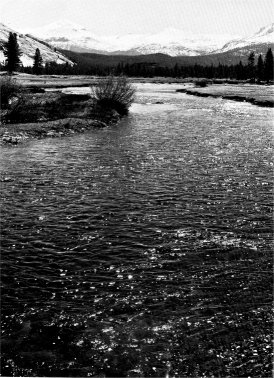

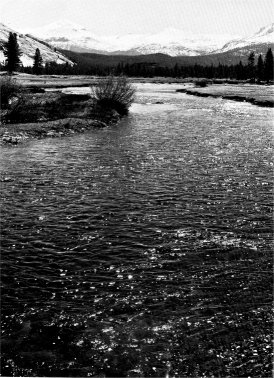

On many mornings in the late summer, before sunrise, the river meandering through Tuolumne Meadows is a monochrome of deep green, flowing endlessly onward. Frequently the air is calm and the water surface in some stretches serenely smooth. A feeding trout breaks the surface, leaving ripples that spread and intersect, creating evolving geometric patterns.

Toward sunrise, birds awaken and a slight breeze ruffles the surface of the river. Then the sun ascends over the eastern crest and bursts upon the towering peaks that rim the meadow, eventually penetrating the lodgepoles with shafts of light which move across the surface of the river like slow, sweeping searchlights.

The deep green water is changed first to blue-green, then, as the light becomes stronger, to an intense aquamarine. The colors change into a kaleidoscope of patterns — earthy browns, pale blues, misty greens, gleaming silver, colors of emerald and colors of cobalt.

The summer spectacle in Tuolumne Meadows is no quickly devised production but a sequence of intense, intricate forces working over long periods of time. It is the result of the long geologic processes that formed the meadows — the shallow seas that once covered the Sierra during the Paleozoic, the upthrust of the Sierra Nevada range during the Cenozoic, and the sculpturing of the granite by the great ice fields of the Pleistocene.

The summer spectacle is produced more immediately by the fragile and interrelated life forms, of which each species exists in its own unique niche - the seasonal storms of the winter months, which drop a blanket of snow on the landscape - the warming temperatures of spring which release the snow from the tight grasp of winter to send it forth in a different form, to nibble and nourish the land - the heat of the sunbaked Central Valley, rising up the Sierra Nevada crest to produce the welcome afternoon thundershowers.

As the focal point where the moisture laden air of the Pacific and the Central Valley meet the cool air of the mountains, this meadow is a summer-long interface where the forces of the sky and the land struggle for supremacy - producing the daily spectacle of life, color, and light in this colossal amphitheater.

There are as many meanings to this spectacle as there are visitors to the park. My first extended experience with the meadows was as a cook at the Tuolumne Lodge. I could look out each morning from my cabin at the changing waters of the Dana Fork. Indulging in the romantic speculations of youth, I wondered whether this superlative environment produced superlative people. Did it fire their imaginations to keener insights and mightier achievements? Or would they feel and think and act the same if the meadows did not exist? The meadows have a strong effect on my own daily disposition. On cloudy, overcast days when the mountain peaks are surrounded by a shroud of thick mist, my psyche is different than at times when the air is clear and crisp and the changing surface of the river gleams like a diadem reflecting a spectrum. The sight gives me special zest, an extra spring to my walk, and an indefinable sense of invincibility.

How much physical environment affects individual character has been argued for centuries, but there can be little doubt that the American character has been powerfully conditioned by the experience of nature on this continent. Frederick Jackson Turner, in his celebrated frontier thesis, argued that the American character did not spring full blown from the Mayflower or from the European roots: “It came out of the American Forest, and it gained strength each time it touched a new frontier”. It may be equally true that the character of the visitor to the meadows gains strength from the special quality of the region’s environment. It is quite enough to experience the constantly changing beauty of the meadows for sheer enjoyment - such as the pleasure that comes from a stimulating conversation or a good song. But there are deeper experiences and they are available daily, as if the meadows were each time a new frontier, a new wilderness, offering strength as well as a sense of participation in the festivals of nature. In the words of one visitor to the meadows: “Who would ever guess that so rough a wilderness should yet be so fine, so full of good things.”

“One seems to be in a majestic domed pavilion in which a grand play is being acted with scenery and music and incense . . . Keep close to Nature’s heart, yourself; and break clean away, once in a while, and climb a mountain or spend a week in the woods. Wash your spirits clean.”

John Muir 1869

[Editor’s note:

the first sentence (only) is from

John Muir My First Summer in the Sierra, chapter 2

—dea.]

Next: Rights for Natural Objects • Contents • Previous: Yosemite as a Process

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_nature_notes/46/2/tuolumne_meadow.html