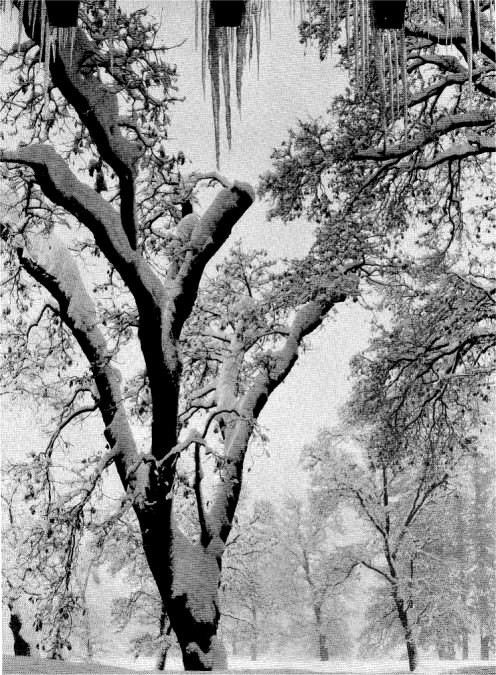

[click to enlarge]

in Yosemite Valley

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Tales & Trails > The Indians of Ahwahnee and the Medicine Man’s Prophecy >

Next: Discovery of Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Yosemite Story

THE STORY of Yosemite begins back generations ago when a large and prosperous race of Indians known as the Ahwaneechees lived in the “deep, grassy Valley” they called Ahwahnee. In this Indian Paradise acorns grew in abundance. Sweet clover and tender grasses covered the floor of the valley. Fish were plentiful in the streams and the forests were alive with game. It was Yosemite’s heydey.

Every fall the Ahwaneechees held a great hunting festival in the Valley, to which they invited their neighbors, the Monos and the Paiutes, from across the Skye Mountains. Down from the crests of the Sierras they came, three and four hundred strong, to exchange their flints and salt and larvae paste for the acorns of Yosemite, and reeds for weaving baskets. For weeks at a time the braves hunted while the women gathered acorns and ground them into meal. Between hunts they played games of chance and skill, and at night, about the council fires, they told stories about the spirits which inhabited the rocks and the waterfalls, and the great chiefs swore undying fidelity to each other with an oratory which made the very walls ring.

Then came a mysterious illness, or “black sickness,” which spread through Ahwahnee and all but exterminated the tribe. Those who survived fled from the Valley, fearing the wrath of the gods they must have offended. And for years Yosemite was avoided. No human being went near it, and it was the golden era for the grizzly bears and the black-tailed deer.

Among those who escaped the epidemic was the great chief of the Ahwaneechees, who took refuge with the Mono Indians and was adopted into their tribe. His son, Tenaya, was born of a Mono woman and lived when a boy among his mother’s people.

When he reached manhood he was persuaded by the Medicine Man of his father’s tribe to return to the valley of his ancestors, taking with him the few descendants of the Ahwaneechees and outcasts from other tribes, and establish

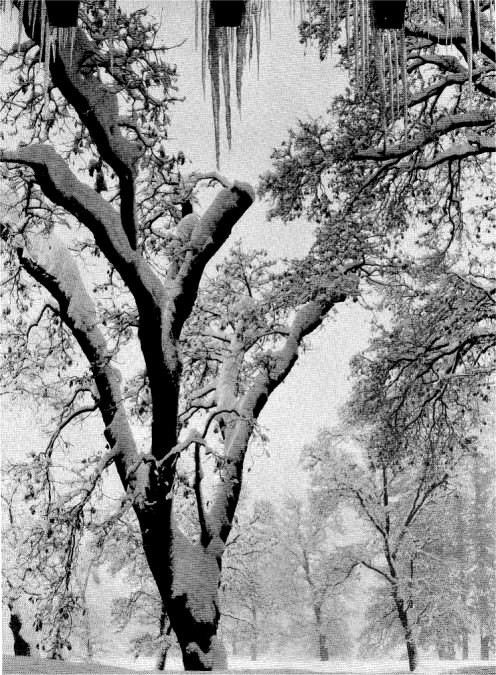

[click to enlarge] |

|

Winter makes magic

in Yosemite Valley |

Returning to Ahwahnee with Tenaya, the old Medicine Man prophesied that as long as the young Chief retained possession of the Valley his tribe would flourish and increase. That if he befriended those who sought his protection no other tribe would come to make war upon him or attempt to drive him from his stronghold. That if he obeyed the patriarch’s counsel he would put a spell upon Ahwahnee which would hold it sacred to him and to his people alone, so that none would dare to intrude there. But he solemnly warned Tenaya against the horsemen of the lowlands, and declared that should they ever enter his valley his tribe would soon be scattered and destroyed, his people taken captive, and he, himself, would be the last chieftain in Ahwahnee.

Arrogant though he was, this warning of the Medicine Man disturbed Tenaya, and the dread of its fulfillment obsessed him, leading, ironically enough, to his downfall—and to the discovery of Yosemite!

For with the discovery of gold in California and the arrival of the gold-diggers in the foothills of the Sierras, trouble with the Indians began. The white men, they claimed, with their hogs and cattle were destroying their acorn crops. They were plowing under fields of grass and clover to plant their own seeds. They fished out the streams and frightened off the wild game.

To retaliate, the natives stole horses and cattle from the miners. They plundered and burned their trading posts. Incited and aroused by the anxious Tenaya, whom they feared, Indians from other tribes joined the Yosemites in plaguing their common enemy, the white man, in an open effort to drive him from the country.

Among the early settlers in that region was one James D. Savage, who had befriended the Indians. It was the burning of his trading post on the Fresno River and the cold-blooded murder of his three assistants there which led to the organization of the Mariposa Battalion to punish and prevent such outrages.

Commissioners were sent out from Washington to try to treat with the Indians,

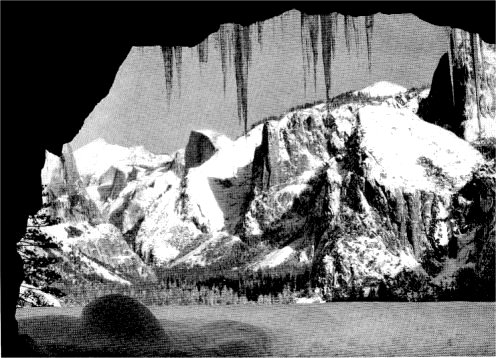

[click to enlarge] |

|

Clouds’ Rest and Half Dome as

they burst upon you, in winter, from the new tunnel road into Yosemite |

But the prophecy of the Medicine Man weighed heavily on Tenaya’s mind. When his runners brought word that the attack upon Savage was leading to reprisals, and that the Mariposa Battalion was then on its way into Yosemite to bring him and his people into the Commissioner’s camp, the wily Chief made one last desperate effort to keep the white man out of his valley. He shrewdly decided to conciliate the Americans by taking his tribe into the White Father’s camp to make peace, intending, always, to return to the mountains as soon as the excitement from the recent outbreaks had subsided.

A few days earlier and he might have succeeded in this strategem. But he delayed too long. Major Savage and his troops were already encamped where Wawona stands today, and there Tenaya encountered them. The old Chief said he had come to give himself up, and that his people were on their way in, but had been delayed by a snow-storm, which had made travel difficult.

For three days Major Savage waited for the Yosemites to appear, then becoming impatient and suspicious he decided to go on. Tenaya did all he could to restrain him, explaining that if the Indians could not get out of the Valley, the horsemen could never get through the drifts to get in. But Savage turned a deaf ear and gave the order to march on, with Tenaya as their guide.

Half-way between their camp and the Valley they met a little band of Indians, men, women, and children, plodding wearily through the deep drifts, silent and disheartened. They were Tenaya’s people. Savage counted seventy-two as they filed past.

“Where are the rest of them?” he asked their chief.

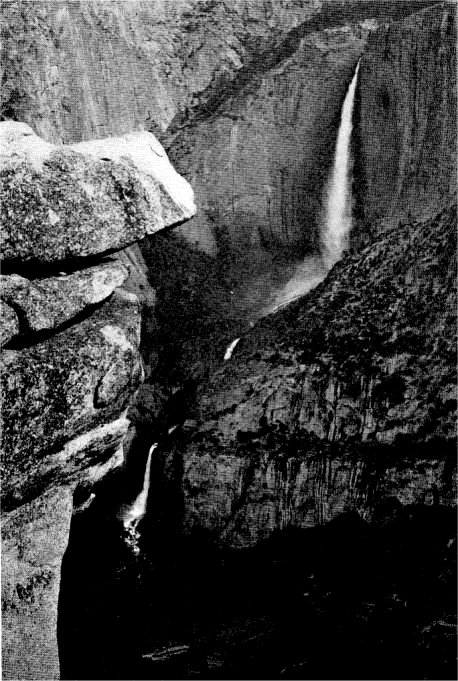

[click to enlarge] |

|

From Glacier Point the flash of

Yosemite Falls and the sound of its thunder dominate the entire Valley |

Tenaya shook his head, indicating that was all that was left of his tribe. The rest, he said, had scattered and gone back to their own people. But Major Savage had learned something of the ways of the Yosemites. Observing that there were no young braves among the band, he gave the order to proceed, sending a grim and disgruntled Tenaya back into camp with the guards and their captives.

Next: Discovery of Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Yosemite Story

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_tales_and_trails/ahwahnee_indians.html