[click to enlarge]

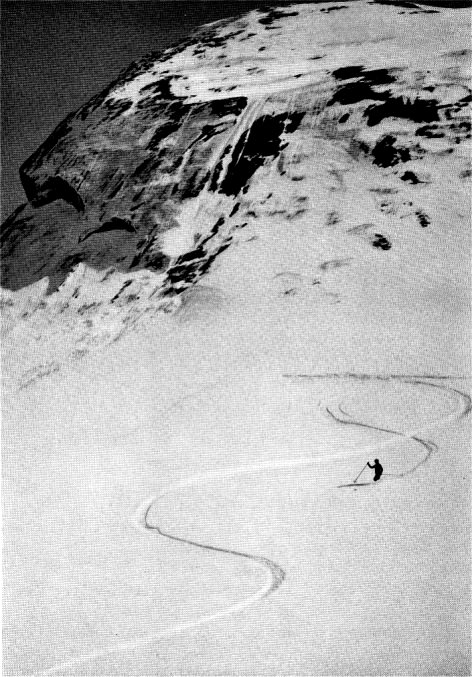

anyone can blaze his own trail

through a landscape of virgin snow

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Tales & Trails > Stage-Coaches and Bandits >

Next: Pioneers • Contents • Previous: Tourist

Not so long ago a cry was heard in the wilderness, “What Yosemite needs is one good carriage road the entire length of the Valley!” and immediately the answer came hack, “Impossible! That would spoil Yosemite! Make it too civilized!”

Nevertheless, this dream was realized, and by 1875 there was not only one good carriage road extending the length of the Valley, but there were three roads into the Valley over which stage-coaches might travel. Lurching, swaying, creaking, dust-enveloped or rain-soaked, Concord Coaches or “Mud-Wagons,” those were the days of real sport, the days of the Cannonball Express, and the days of bandits!

Travel on wheels was really de luxe and one writer tells enthusiastically of improved transportation facilities which enabled one to reach Yosemite in three days from San Francisco, the round trip costing only sixty dollars! And those

[click to enlarge] |

|

Up in the Yosemite ski country

anyone can blaze his own trail through a landscape of virgin snow |

Until the Horseshoe Route was established the trip took two days from Stockton, cutting down the saddle days by one. But with the coming of the Cannonball Express, via the Horseshoe Route, this time was reduced to one day, though a long and strenuous one. Horses were changed at ten-mile intervals along the entire route, which is followed today by the Horseshoe Auto Stages. Hurtling down mountain sides, over perilous roads, fording rivers with the water hub-deep, thumping and bumping a chained log behind down the steepest grades where brakes alone would not hold, flashing around hairpin turns to encounter a freight wagon on a narrow road, those are some of the thrills tourists to Yosemite are spared today.

Though the hold-ups on those stages were not frequent, they occurred often enough to spice the trip with real adventure. And their conversational value, for ever after, was well worth the cost of the experience. The Bad Men of the West in that day had something of an operatic charm about them which often compensated for the inconvenience of being robbed. For example, a bandit holding up one Yosemite stage remarked, generously, before taking up his collection:

“Boys, if any of you haven’t got more than fifteen dollars you can keep it, for I’ve got that much myself!”

A story is told of one highwayman who, alone, held up a string of five Yosemite stages. After he had thoroughly fleeced his victims he presented each with his card, on which was printed “The Black Kid.”

“Thanks!” remarked one of the passengers wryly, “always nice to know where to get hold of a professional.”

“Black Bart,” one of the most famous bandits of the early eighties, made his last hold-up in the Yosemite region. He always worked alone, but one of his favorite stunts was to prop the muzzles of empty guns over the top of surrounding rocks, and talk occasionally to these supposed confederates as he robbed the stages. His last hold-up occurred three miles out of Copperopolis. He robbed a stage of a Wells Fargo treasure-box containing $5,000. But in his escape he dropped his handkerchief, which contained a laundry mark. This led to his identification. With a record of twenty-eight hold-ups to his credit he had never taken a single life, and usually operated with a sawed-off shotgun which was unloaded.

Before the novelty and comparative comfort of stage-coaches had worn off, a railroad had been built into Yosemite, and soon after automobiles began rolling in. Not rolling, perhaps, but chugging. For those earliest automobiles were little short of the wonders they had come to see.

In 1907 the Yosemite Valley Railroad was completed and an end had come to the stage-coach era, but it was another six years before the Government allowed automobiles to drive into the Valley. In 1900 one intrepid motorist had entered Yosemite, but no others were allowed until 1913. Even after pressure had been brought to bear and the Government had removed the ban against them, they were admitted very grudgingly and regarded with frank disfavor. Immediately they appeared in the Valley they were pounced upon and chained to a log for the duration of their stay.

The Commandments regarding automobiles were very strict. Five minutes were allowed for the loading and unloading of passengers and baggage, after which the car was rushed, like an infectious case, to the garage, or out of the Park.

No person could smoke while driving an automobile in the Park.

Speed limit was six miles an hour, except on straight stretches, where, if no approaching team was visible, ten miles was tolerated.

On the El Portal road the speed limit was five miles an hour inbound and six outbound!

Pioneers of the Covered-Wagon Days were no braver than the drivers of the first automobiles into Yosemite. Our worst mountain roads today are probably better than the best then. The small light cars of those days could neither straddle nor ride in the wagon ruts. Roads were so narrow that I know of one instance, at least, where two motorists met and before they could pass each had to unscrew his license plate. Another motorist tells of reaching the Valley on her last gallon of gasoline and having to wait in Yosemite for three weeks before anyone would risk bringing more in on a freight wagon, fearing it would explode. Others tell of pouring sardine oil into the carburetors and White Rock water into the radiator to finish that long last mile into camp.

One by one the difficulties governing travel into Yosemite have been overcome until today, with the choice of a train, luxurious motor buses, a paved All-Year Highway over which you can drive your own car any day of the year, a landing field at Wawona for airplanes, and the shortened and improved road to the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees, registration of visitors to the Park has mounted from that original tourist party of five to half a million annually—and the number is always increasing.

The whole Yosemite story is told in its transportation system. For every moving thing across the Sierras has left its trail. First the rivers, which carved the valleys. Next the glaciers, slow-moving ice packs which left behind them the shining pavements of the High Sierras. After them came the wild-game trails, faintest traces through the forests. In time these were widened by Indian feet, and later, pounded deeper by horses’ hoofs. Next came the wagon ruts, then iron rails, and finally the smooth paved highways for automobiles; and at the end these pavements peter out again into horse trails, horse trails to footpaths, footpaths to game trails, back to the shining glacial pavements where travel all began.

The Yosemite cycle is complete.

Though the early tourists to Yosemite may have had to put up with such discomforts as muslin curtains between the bedrooms instead of walls, their lot was not such a hard one. There were compensations in royal breakfasts of brook trout, venison, and bowls of wild strawberries, which the Indians used to gather, and in the ten dollars a week one used to pay for room and board at Hutchings House.

In the Valley then there was that friendliness and informality which you still find around the High Sierra Camps. For the camaraderie of shipboard is equaled only by that found out upon the open trail, or fostered around a crackling campfire.

[click to enlarge] |

|

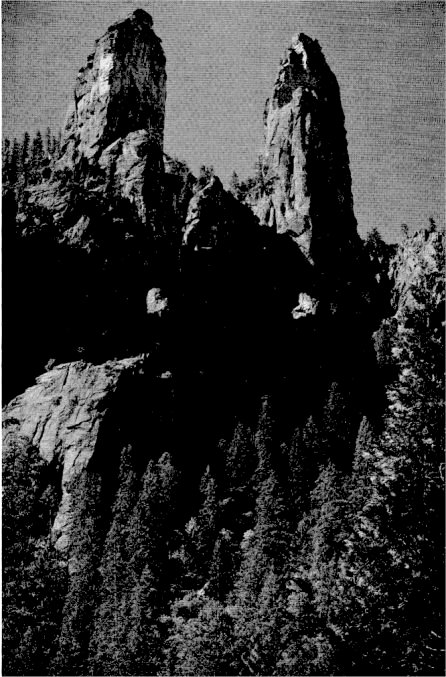

Cathedral Spires suggest the ruins

of some mighty temple of the gods |

A glance at the Grand Register of the old Cosmopolitan Hotel, loaned to the Yosemite Museum, will prove what a magnet the Park was for all kinds and conditions of people. This register is one of the great relics of Yosemite’s Past. A foot in thickness, morocco-bound and silver-mounted, it was made to order for the proprietor of the Cosmopolitan Hotel by H. S. Crocker Company of San Francisco in 1873. In it are the names of four United States Presidents, U. S. Grant, R. B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, and Theodore Roosevelt. Under the signatures of Isabelle Jones or Tommy Black are those of distinguished generals, foreign lords, counts and dukes, including Duke Alex of Russia, and Lily Langtry, London’s darling. Yosemite attracted them all, even as it does now, and there was no telling what kind of adventure might be sitting to the right or left of you in those days of rude shelter and general baths. And after all the other glories of Yosemite had been admired, there wasn’t anything more appreciated than those bathtubs and full-length mirrors of the Cosmopolitan Hotel which had all been carried in on mule-back over fifty miles of mountain trails.

In the winter of 1932 a fire destroyed this famous old hotel, which for years had been used as company general offices in the “Old Village.” Along with Black’s and Leidig’s, Barnard’s and Stoneman House, Casa Nevada and the old Hutchings House, it is now only a memory. Yet in its day the Cosmopolitan Hotel was the Ahwahnee of Yosemite Valley, and who knows what will succeed the present Ahwahnee Hotel fifty years from now!

Next: Pioneers • Contents • Previous: Tourist

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_tales_and_trails/stagecoaches.html