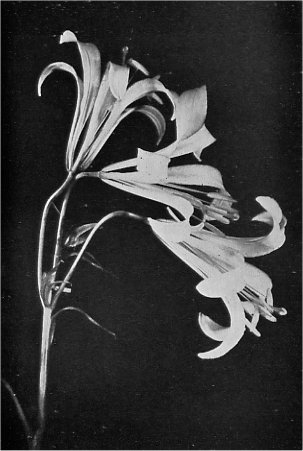

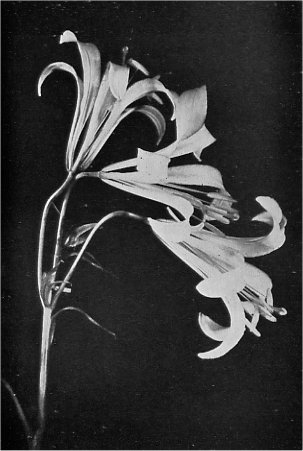

PLATE XXIV

Washington Lily (Lilium Washingtonianum)

A fine species which fills the Yellow Pine forest with a

delightful fragrance

Photo by A. C. Pillsbury

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Handbook > Flowers >

Next: Camping and Mountaineering in Yosemite • Contents • Previous: The Giant Sequoia

By Willis Linn Jepson

Professor of Botany, University of California

1Based upon the botany series of the LeConte Memorial Lectures

delivered by Dr. Jepson in Yosemite, June, 1918.

Pages 253, 258,

259, and 260

were, under Dr. Jepson’s direction,

either written or expanded by me. This paper was also used by

me for reference in preparing my article in the

Sierra Club Bulletin

for January, 1921, but credit for the portions on the Snow

Plant and one or two other species was inadvertently omitted.

Elizabeth Van E. Ferguson,

Research Assistant.

Yosemite National Park offers a remarkably rich field for the botanist. The same factors which determine the great diversity of animal life influence to a much greater degree the species and forms of plant life. Some plants have become highly specialized to endure the many months of drought in the semi-arid foothills, while others have developed a hardiness which enables them to exist in the bleak reaches above timberline. Even in the middle regions where optimum conditions attain, the exhuberant abundance of wild blossoms changes in character with each change of site; each species seems to have its own niche, whether it be in swamp, on fertile hillside, or on desiccated granite barrens. Indeed, so great is the range of natural conditions to be encountered in the park between the foothills and the mountain glaciers that there are no less than twelve hundred species and varieties of flowering plants and ferns native to this area. While most of these are typical of the entire Sierra Nevada, many are exceedingly rare, and a few species are only known from small areas within the park.

By whichever route the traveler enters Yosemite, he will pass through the shrub formation known by the Spanish name chaparral. So densely does this society, clothe its area in the Upper Sonoran or Foothill Zone that it is often impossible to force one’s way through it. The various shrubs which go to form this close cover are of much the same stature and aspect, and form a remarkably uniform population on exceedingly dry and well-drained slopes. The excessive drought, the high summer temperature, and the rocky or gravelly nature of the soil are the chief factors which have caused these various chaparral shrubs to develop many characteristics in common; of these the most striking are their dwarf habit, reduced leaf surface, small flowers, hard close-grained wood, and rigid thorny branchlets. It is only superficially, however, that these shrubs are alike. They are derived not from one family, nor two, nor three, but represent the pioneer spirit in many different stocks which have successfully met the conditions imposed by Nature in the chaparral area.

One of the most important and abundant of these shrubs is Buck Brush (Ceanothus cuneatus), a gray bush five to eight feet high with tough thorny branchlets, opposite leaves, and hard close-grained wood. It is everywhere abundant, and its short blunt spurs make it a terror of the cattlemen riding the range. The small white flowers are in themselves insignificant but a profuse production of small honey-scented clusters

PLATE XXIV Washington Lily (Lilium Washingtonianum) A fine species which fills the Yellow Pine forest with a delightful fragrance Photo by A. C. Pillsbury |

In approaching the Valley from El Portal, if early enough in the year, one will be rewarded with the sight of that unusual glory, the Redbud (Cercis occidentalis). Before the foliage even hints at showing its tender green leaves the tree is shrouded in a cloud of red blossoms. It belongs to the Pea Family and in summer its branches are heavily hung with purplish pods. Along the streams at the same altitudes is the Wine Bush or Sweet Shrub (Calycanthus occidentalis), a bush with large opposite leaves, aromatic flowers, and red-brown sepals and petals which are borne on a cuplike base. Farther up the canyon of the Merced one of the most pleasing sights in early summer is the Philadelphus (P. lewisii var. californicus) which is similar to the Syringa of Eastern gardens. It forms fragrant thickets along the stream banks and because of its somewhat orange-like flowers is often called Mock Orange. It is perhaps rivaled by its associate, the Bladdernut (Staphylea Bolanderi) which grows in the canyons of the foothills, especially above El Portal near Pulpit Rock. The Bladdernut has its leaflets in threes and covers itself with white drooping flower clusters which later develop into curious bladder-like three-horned seed pods. It was first collected in 1874 by Dr. Henry N. Bolander, one of the early botanical explorers of the Yosemite region.

Everywhere the shrubs lend interest and charm to the Mountain sides and the open forest floors or valley levels. Foremost among these stands the Deer Brush (Ceanothus integerrimus) with its tall slender stems, scattered foliage, thin leaves, and abundant masses of delicate white blossoms. The foliage of this bush is eaten by the deer and it is also an important browse for cattle. Chemical analysis indicates that its leaves have a higher nutritive value than those of any other native shrub. It is when the Deer Brush is in bloom, however, that it most attracts the eye of the traveler. The thickets with their dainty plumelike flower-clusters borne aloft on slender branchlets form a billowy mass of white over considerable forest areas. A less common species is a close relative, the Sweet Birch (Ceanothus parvifolius), which is found in the Mariposa Grove, about Chinquapin, in the vicinity of Grouse Creek, and at similar altitudes. It inhabits open spots in the forest where its stems spread out and form the root crown in a somewhat wheel-like fashion. Its diminutive shiny leaves and small clusters of flowers in delicate shades of blue make it an attractive asset of the forest floor.

As the traveler enters the Valley his views of the Merced River will often be enhanced by the abundant bloom of the Western Azalea (Rhododendron occidentale) as it contests for a place among the willow thickets. In June or July its sweet fragrance charms one to follow the stream and see its beauties. often the great flower-clusters nod to the stream and almost dip their delicate orange and white petals into the swiftly running water.

But it is the Valley floor with its riotous wealth, of color which in favorable seasons shows best the variety of the native vegetation. In late spring or early summer the meadows are carpeted with great masses of bright flowering annuals and taller brilliant perennials. The delicate Canchalangua (Erythraea venusta) with its showy clusters of bright pink flowers; the taller Collomia (Gilia grandiflora) with its dense heads of dainty funnelform flowers, cream to almost salmon in colour; many patches of golden Mimulus or Monkey Flower; countless blue flowers, such as the light blue Pentstemon (P. confertus) with its flowers in whorls on tall stems; tall blue "Forget-me-nots" (Lappula velutina); tiny dark blue Collinsia (C. parviflora) and the larger almost white Collinsia, tinctoria; the red Indian Paint Brush (Castilleia miniata); the brilliant scarlet Pentstemon (P. bridgesii) with lance-shaped leaves and funnelform corolla about one inch long; and quantities of golden Buttercups (Ranunculus occidentalis var. eisenii), all go to form the brilliant mosaic of large sheets and pools of color on the Valley levels.

At altitudes of 3600 to 5000 feet, after the shallow springtime pools have evaporated, these areas become midsummer beauty spots with a thick growth of Downingia montana. This is a little Lobelia with delicate jewel-like blossoms, the upper lip very small with two minute lavender lobes, the lower lip of three broad-spreading lobes, white at the throat, and with a bright blue border. A mass of these dainty blue flowers is the loveliest sight imaginable and may be seen in Hetch Hetchy Valley and on the Hog Ranch Road to Crocker’s Station.

One of the plants found in Yosemite Valley and at similar altitudes which receives especial attention from the traveler is the Bleeding Heart (Dicentra, formosa) Its leaves are finely cut and its flowers are pendulous in clusters from the summit of the stem. The flower itself is flattened, of a rose-purple color, and about three fourths of an inch long.

Another striking plant of moist or swampy places is the Scarlet Monkey Flower (Mimulus cardinalis). The rich green foliage, soft with hairs, makes a beautiful setting for the large brilliant flowers. These gorgeous plants may be seen in several places in the Valley, usually by streams or near the bases of the waterfalls.

One of the remarkable sights of the upper reaches of the Valley in midsummer are the fields of tall yellow Evening Primroses (Oenothera biennis). They have very handsome large golden flowers which open at twilight and close again in the middle of the following day. In favorable seasons the dry open fields about Yosemite are often yellow with these stately plants. Many of the finest groups, however, are now a thing of the past, due to the mowing of the meadows for wild hay.

In the edges of brushy thickets one finds the Wild Ginger (Asarum Hartwegi) with its broad mottled leaves and its curious purple flowers close against the ground. It is one of the most singular plant inhabitants of the Valley floor and is always worth searching for in May and June.

In dry spots near the Yosemite Black Oaks, the Sierra Milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) develops its bunches of highly specialized pink or reddish-purple flowers above its white hoary leaves and is a most interesting plant on account of its habit of catching and imprisoning flies.

Along the roads one may see in May or June the White Mariposa Lily (Calochortus venustus). This is one of the handsomest of all Mariposas and is remarkable for its range of color. Along the Wawona Road one form has deep wine-red petals which are darker toward the middle and are crossed below by a broad yellow band; still other plants, the more usual form, are nearly white with a dark brown eye surrounded by yellowish shadings.

The Lily Family is well represented by many other interesting species. The Tiger or Leopard Lily (Lilium pardalinum) occurs in such places as Bridalveil Meadows where as many as twenty-eight flowers have been counted on a single plant. The Little Tiger Lily (Lilium parvum) has flowers about half as large and grows in moist meadows at higher elevations.

On the walls of the Valley are several rarities, one of them being the Cliff Buttercup (Ranunculus hystriculus). Its sepals are white and petal-like and the petals, which are small and inconspicuous, are developed as spoon-shaped nectaries. The whole flower looks more like an anemone than a buttercup and has a great historical interest as it is in reality one of the most ancient of flowering plants. It grows on cliffs and ledges where it is reached by the spray from Yosemite Falls, Vernal Falls, Nevada Falls, and other cataracts about the Valley. It is as delicately beautiful as it is rare.

Leaving the Valley and passing into the main pine belt (Transition Zone) one finds many interesting plants. Here the Deer Brush and Manzanitas cover great areas. A very abundant plant is the Mountain Misery (Chambaetia foliolosa). There is no mistaking it. The strawberry-like flowers (which it comes by honestly since it is a member of the Rose Family) and the fernlike foliage mark it distinctively. The woody stems grow six inches to two feet high and colonize, almost to the exclusion of other herbs, miles and miles of the open slopes and flats beneath the Pines in the Yellow Pine belt. It is sometimes called Bear Clover or Tar Brush, but the true folk name, Mountain Misery, is a better term, for it comes right from the soil and is born of the daily work and experience of the mountain rancher. He cannot trail his animals through it, for they leave little or no track in this growth; the foliage has a tarry secretion which gums up his clothing; and the herbage is offensive to his cattle and so it is useless as a fodder plant. To the mountain rancher, then, this herb is the last word in expression of the day’s discontent and inadequacy. To many a mountain-lover, however, its spicy odor suggests the many drowsy sunny days spent beneath the pines.

Beneath the Yellow Pines on the road from Yosemite to Wawona the Tuolumne and Merced Big Tree Groves the ground is often covered with the green carpet of the Mahala Mats, a species of Ceanothus. It has small clusters of blue flowers, leaves spiny at the tips, and distinct horns on the seed pods. The mats are closely grown and, while irregular in shape, often become five to fifteen feet broad.

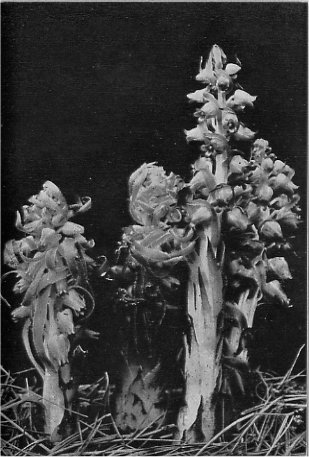

Of all rarities in the park no other plant excites so much popular interest, perhaps, as the Snow Plant (Sarcodes sanguinea). It is a very Mephistopheles amongst plants, and its dazzling red color has exercised a strange and almost weird fascination upon the popular mind. The whole plant—flowers, bracts, and stems alike—is of a bloody red hue. It springs up from the leafy mold of the forest floor, and (as the police judge would say) is without obvious means of support, since it has no chlorophyll, no green leaves, to manufacture its own food as most other plants must

PLATE XXV

Photos by A. C. Pillsbury |

One of the great rarities of this region is a species of Lewisia (Lewisia yosemitiana) which grows in the granite sand on top of the domes about Yosemite and nowhere else in the world. The white flowers rise from underground roots and open out on the sand like stars set in the very crowns of the domes. These plants are very delicate as well as very rare and should never be disturbed, since they will fall to pieces in one’s hand if dug up from the place where they grow, as if in resentment at man’s interference with them. They, however, are well worth seeking for field study by lovers of rare plant life.

In dry open swales of the great Yellow Pine Forest one comes upon the tall stalks (four to six feet high) of a great white lily bearing sometimes ten or fifteen flowers, which now is called the Washington Lily (Lilium Washingtonianum) although that pioneer botanist, Dr. Kellogg, distinctly named it the Lady Washington Lily, after Martha Washington, the first lady of the land, as he said.

On sandy pine barrens great areas may be crimsoned with little Mimulus (M. torreyi and M. bolanderi). Here also Pussy’s Paws (Calyptridium umbellatum) often add to the pink or red carpet of the forest floor. The stems radiate from a central rosette of leaves which lie flat on the ground and bear at the ends an involved soft mass of flowers, forming a cluster which whitens with age and suggests the common name by which the plant is known. In sunny spots the tall scarlet Gilia (G. aggregata) form brilliant patches which greatly attract the humming-birds in their search for hidden sweets. Its corollas are tubular and about an inch and a half long, the exserted stamens inserted in the notches between the lanceolate lobes. Still other areas are blue with other Gilias such as G. leptalea, the flowers of Which are about one half inch long.

On granite sand spaces one may find many acres covered with Golden Stars (Brodiaea aurea), a species of Brodiaea which is related to the blue Grass Nuts of the foothills. In the forest one meets the Nuttall Mariposa Lily (Calochortus Nuttallii), its almost white, flowers bearing an inky spot about the gland at the base of the petals. At slightly higher altitudes may be found the tiny Sierra Pussy’s Ears (Calochortus nudus) with its small white hairy petals.

Sandy areas will often be clouded by the delicate little white flowered Eriogonum (E. spergulinum). It is a dainty little annual with small white flowers borne on hairlike stalks which give it a very airy and fragile appearance. It has somewhat the appearance of the Baby’s Breath of our gardens and is in places so abundant that it forms a great Milky Way through the forest which is as beautiful by moonlight as by day. Another delicate white flowering herb with a diffusely branching flower cluster is the Silver Tails (Potentilla santolinoides). This may be easily recognized by its peculiar caterpillar-like leaves which form a silvery rosette at the base.

Rocky or gravelly slopes are often resplendent with lovely hanging gardens of Pride of the Mountains (Pentstemon menziesii). This brave plant grows in the most unhospitable places but developes into a tall and bushy plant with ovate finely toothed leaves and beautiful trumpet-shaped flowers which are reddish in color. Wherever this Pentstemon appears it is indeed the Pride of the Mountains, blooming profusely as it does in the midst of rocky barrens.

The high mountain meadows above Yosemite are frequently wonderful wild gardens. In one of those meadows it was once the author’s good fortune to see fully twenty thousand plants of the Jeffrey Shooting Stars (Dodecatheon Jeffreyi) in full bloom. This is a Plant which resembles the Cyclamen of our gardens. Among the Shooting Stars one often finds the feathery White flowers of Polygonum (P. bistortoides); the slender stems are very erect and bear at the summit a close Mass of small white flowers which at a distance look like neat white flags. A meadow full of Shooting Stars and this white Polygonum has the appearance of a fresh and orderly mountain garden. The stream which usually meanders through these rich meadows is often lined with clumps of the Labrador Tea (Ledum glandulosum). This is an evergreen shrub with shiny oval leaves which, due to the resin which they contain, are peculiarly fragrant when crushed. The white flowers are grouped at the ends of the branches in flat-topped clusters. By the stream bed one may often find lovely robust plants of the large Pink Monkey Flower (Mimulus Lewisii) which replaces the scarlet species of the Yosemite and lower valleys. The flowers are showy light pink, and plainly two-lipped but the two lips are similar. In these swamps grow the quaint Elephant Heads (Pedicularis attollens) with its slender rose-pink spikes. The name Elephant Heads arises from the peculiar corolla with its hooded upper lip prolonged into a curved beak or proboscis. Associated with the foregoing one finds the blue Pentstemon (P. confertus) which is not so tall nor so many flowered as that at lower altitudes. Often a marshy stretch may be covered with the pale creamy cups of the Marsh Matigold (Caltha biflora).

The different meadows often vary greatly in their plant composition. On the one hand one may see meadows filled with flowers which grow higher than the waist and so thickly that it is impossible to step without-treading down many plants. There are Rein Orchis (Habenaria unalaschensis) with long tresses of small white flowers; many species of Lupins, the largest and most attractive of which bears great masses of showy blue spikes (Lupinus longipes); the great yellow Cone flower (Rudbeckia californica) standing shoulder high and ending in a single conical head; the purple Fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium) which raises its long wands to the breeze; and the curious

PLATE XXVI The Snow Plant (Sarcodes sanguines) This remarkable plant, which is entirely fire-red, is one of the most curious species in the Park Photo by A. C. Pillsbury |

A common shrub at altitudes of five thousand to eight thousand feet is the Green Manzanita (Arctostaphylus patula). The stems of this manzanita are three to six feet high and much branched so as to make a spreading shrub. The leaves are very green and fresh looking and the bell-shaped flowers deep pink and in compact terminal clusters. More or less associated with it at the higher altitudes one finds the Bitter Cherry (Prunus emarginata), its crimson cherries most attractive to the eye in August but shocking to the taste. It forms dense thickets on moist slopes and is often quite abundant.

Throughout the Yosemite region one is impressed with the number of species of Eriogonum. One of these which is not uncommon between five thousand arid seven thousand feet is the Sulphur Flower (Eriogonum umbellatum), noticeable for the spots of yellow which it lays upon many a stony slope or rocky crag. 0n Lambert’s Dome one will find another kind, Lobb’s Eriogonum (E. Lobbii) whose white flowers are Much larger and, since the stem reclines upon the granite rock upon which the plant grows, it seems as if they weighed down the stalk which bears them. At the high altitudes, generally from 7500 to 9000 feet, there appears the Snow Brush (Ceanothus cordulatus). This is a low flat-topped shrub which forms circular mounds five to ten or fifteen feet broad and commonly one to three feet high with olive or grayish branches and rigid or often spinelike twigs. Its low compact growth is the result of the heavy burden of snow that it must carry for several months of the year. In the summer it also carries a white burden, but this time it is light and fragrant instead of heavy and cold. Whether it is the abundance of white bloom in the summer or the snow of the winter which causes this species to be called Snow Brush is disputed, but its distinct habit and abundant occurrence at higher altitudes always focuses the attention of the mountaineer.

The swampy, alpine meadows of the Hudsonian Zone (at about 9000 to 10,000 feet) often possess an interesting inhabitant of the Heath Family. The little Kalmia (K. Polifolia var. microphylla) with its curious pink bloom carrying the anthers in pockets of the corolla, is always a quest with the climbers who know rare plants. If one watch these meadows carefully he will see the tiny pink or white bells of the Dwarf Bilberry (Vaccinium caesspitosum) close against the ground. On gentle slopes moist with seepage water from the snow banks above, one finds the Snow Fairies (Lewisia Pygmaea), tiny plants with a few white star flowers. Two other diminutive shrubs of the Heath Family also grow at these high altitudes. The Red Heather (Bryanthus Breweri) has stems densely clothed with linear leaves and ending in a cluster of red flowers with conspicuous darker red stamens; it has the greater altitudinal range of the two heathers and is often quite abundant. The White Heather Bell (Cassiope Mertensiana) is usually found with the Red Heather at the higher altitudes; it grows in heavy masses along the Lyell Fork of the Tuolumne and picturesquely decorates the margins of most high mountain lakes.

As the traveler climbs the high ridges and peaks and passes upward beyond the limit of trees he is conscious that he is approaching the limits of life for both plants and animals. In consequence, his interest is intensified in those plants which occupy the frontiers of the earth’s vegetation and typify the Boreal Zone. Due to the high actinic quality of the light, most of these plants possess intensely pure or delicate colors and tell the climber that he has reached a world different from that at lower altitudes. In their reproductive season these flowers appear very fragile and seem in strange contrast to their harsh and wild surroundings. If closely examined, however, it will be found that the permanent portion of the plant body is extremely condensed at or below the surface of the ground and is well fitted for the long arctic winter and the daily changes in temperature from freezing to summer mildness which occur even in July and August at 9500 to 13,000 feet.

Those alpine plants which are extremely condensed and developed laterally are technically characterized as "Cushion plants." In this form of plant body the stems branch and rebranch, forming with the leaves a closely interlaced cushion-like vegetative body resting on the ground. From this surface the flower stalks arise. The Alpine Eriogonum (E. incanum) illustrates this high montane vegetative habit as does also the little golden Draba (D. Lemmoni), its leaves forming close rosettes at the base and its bright yellow flowers with the petals in fours. One of the most handsome of these plants is the Alpine Phlox (P. Douglasii), its cushion covered with white flowers, long to be remembered as a thing of beauty. Two alpine Erigerons, dwarfs with daisy-like flowers, inhabit the highest peaks. E. compositus has leaves toothed or lobed at the apex, while those of E. ursinus are entire.

The second type of alpine plant is frequently much dwarfed but does not develop the body laterally into a distinct smooth cushion. Like the cushion plants they often have, however, most delicate or showy flowers. One of the most glorious of these high mountain species is the Yellow Columbine (Aquilegia pubescens), a lovely graceful plant to which the wild grandeur of its rocky surroundings is an almost dramatic foil. It grows on high ridges at about eight thousand to ten thousand feet and has large and handsome flowers which run through a considerable gamut of colors from yellow, white, or cream to pink or lavender. It is a very aristocrat among the Columbines, quite different from the modest red-flowered sort which grows in the Valley. This latter is the same as the common Columbine (Aquilegia truncata) of the Coast Ranges.

Between eleven thousand and thirteen thousand feet one finds the Alpine Buttercup (Ranunculus oxynotus) which, in a modified form, extends northward through Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia to Alaska and as far as the Bering Sea where it is found almost at sea-level. It is a characteristic Buttercup with deep golden yellow corolla, the only one of its genus in the alpine Sierra. Another true

PLATE XXVII

Photos by A. C. Pillsbury |

Much sought by mountaineers is the Sierra Primrose (Primula suffrutescens), a handsome but small red-flowered plant with very shiny, toothed leaves which grows on the rockiest and highest peaks. Equaling it in interest are the sky-blue Polemoniums (P. eximium) which are sometimes called Sky Pilots, their petioles crowded with tiny leaf segments and the stems ending in dense clusters of lovely blue flowers which defy the barrenness of their surroundings. Little Alpine Willow trees an inch high (Salix tenera) further testify to the arctic character of the highest Sierran peaks. On these same peaks grows the Alpine Sorrel (Oxyria digyna), an interesting little plant of rock crevices with pinkish insignificant flowers and roundish cordate leaves.

The Steer’s Head (Dicentra uniflora) is another reward to the alpine climber to such high places as Mount Dana, Macomb Ridge, and Tower Peak. Its delicate blossoms borne on slender naked stems two or three inches high, come up at the edge of snow banks and sometimes in crevasses of snow near the margins of bowlders. The flowers are of very singular construction, the lateral sepals spread out in such a way as to answer to the horns of a steer; the two inner Petals are so constructed as to form the snout, and the inner sepals or forelocks point to the eyes, which are furnished by the shoulders of the petals. These flowers hang on their stems in such a manner as to suggest drowsy cattle, their heads cocked a bit as if half disturbed by an intruder and mildly surprised. Its singular appearance and its rarity give this plant a unique interest, to which may be added the observation that perhaps no other species of our alpine flora is so typically a relic of preglacial times.

The flora of the Sierra Nevada comprises one of most marked and distinct units of vegetation of the earth’s surface. The Yosemite area is thoroughly typical of it, and not elsewhere on the Sierra chain can a transection of it be studied to better advantage than here. All the flowering formations are remarkable, and each in its best seasons has its own peculiar interests. This fact is singularly true because primitive conditions prevail over most of the area, and even in the foothills undisturbed plant societies may still be found by the explorer; while within the park limits the native plant life still reflects the old-time glory of the natural gardens of the Sierras.

Armstrong, Margaret, 1915. Western Wild Flowers (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, N. Y.) pp. i-xx + 596, 500 illus., 48 col. pls.

Congdon, J. W., 1891. Mariposa County as a Botanical District. Zoe, 2: 234; 3: 25, 125, 314.

Hall, H. M., and Hall, C. C., 1912. A Yosemite Flora. (Paul Elder & Co., S. F.) pp. i-vii + 1-282, 11 pls., 171 figs.

Hutchings, J. M., 1888. In the Heart of the Sierras. (Pacific Press, Oakland) pp. 496, pls., illus. "The Shrubbery and Flowers of Yosemite" on pp. 361-362, "The Snow Plant" on pp. 465-466.

Jepson, W. L., 1911.

Flora of Middle Western California. (Associated

Students Store, Berkeley.) Edition 2, pp. 1-515.

1909-1914. Flora of California. (Associated Students

Store, Berkeley.) pp. 1-528, figs. 1-105.

1912. "The Steer’s Head Flower." Sierra Club Bulletin,

8: 266-269, fig.

Parsons, M. E., and Buck, M. W., 1909. The Wild Flowers of California. (Cunningham, Curtis & Welch, S. F.) pp. i-cvi + 1-417. (Descriptions and illustrations of the most conspicuous species.)

Next: Camping and Mountaineering in Yosemite • Contents • Previous: The Giant Sequoia

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/handbook_of_yosemite_national_park/flowers.html