| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > 100 Years in Yosemite > Hotels and Their Keepers >

Next: East-side Mining • Contents • Previous: Explorers

|

|

|

| Woodcut from the first edition (1931) |

The early public interest manifested in the scenic beauties of Yosemite prompted a few far-sighted local men of the mountains to prepare for the influx of travelers that they felt was bound to occur. J. M. Hutchings had no more than related his experiences of his first visit in 1855 before Milton and Huston Mann undertook the improvement of the old Mariposa Indian trail leading to the valley. The next year Bunnell developed a trail from the north side of the gorge. The first visitors were from the camps of the Southern Mines, chiefly, but there were a few from San Francisco and interior towns, as well. During those first years of travel the few visitors expected to “rough it”; they were men and women accustomed to the wilds, and comforts were hardly required. Yet those pioneer hotelkeepers who had provided crude shelters found that their establishments were patronized. Hotelkeeping takes a place very near the beginning of the Yosemite story.

The valley was then public domain. Although unsurveyed, it was generally conceded that homesteads within it might be claimed by whosoever persevered in establishing rights. The prospect of great activity in developing Fremont’s “Mariposa Estate” caused certain citizens of Mariposa to turn their attention to Yosemite Valley as the source of a much-needed water supply. Bunnell reveals that commercial interests had designs upon the valley as early as 1855. A survey of the valley and the canyon below was made in that year by L. H. Bunnell and George K. Peterson with the idea of making a reservoir.

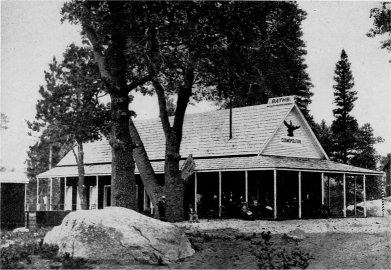

The Cosmopolitan, 1870-1932 |

The Lower Hotel, 1856-1869 |

The first house to be constructed there was built in 1856 by the company interested in this water project. Bunnell states: “It was of white cedar ‘puncheons,’ plank split out of logs. The builders of it supposed that a claim in the valley would doubly secure the water privileges. We made this building our headquarters, covering the roof with our tents.”

The first permanent hotel structure was also started that year. It became known as the “Lower Hotel.” During the next decade it and the Upper Hotel found no competitors. At the close of the ’sixties, however, the hotel business of Yosemite Valley flashed rather prominently in the commerce of the state.

A volume might be written on the efforts of honest proprietors to serve the early tourist; on the scheming of less scrupulous claimants to capitalize on their Yosemite holdings; on the humorous reaction of unsuspecting visitors within the early hostelries; and, finally, on the story of later-day developments which now care for the throng that, annually, partakes of Yosemite offerings. The full history of Yosemite hotels is eminently worth the telling, but the present work will be content in pointing to interesting recorded incidents in the story.

Messrs. Walworth and Hite were the first to venture in serving the Yosemite public. Hite was a member of that family whose fortune was made from the golden treasure of a mine at Hite’s Cove. Walworth seems to have left no record of his affairs or connections. The partners selected a site opposite Yosemite Falls, very near the area that had been occupied by Captain Boling’s camp in 1851, and set up their hotel of planks split from pine logs. The building, started in 1856, was not completeted until the next year, and in the meantime a second establishment was started near the present Sentinel Bridge, so the first became, quite naturally, the “Lower Hotel.” Cunningham and Beardsley, the same Beardsley who packed Weed’s camera in 1859, elected to finish construction of the Lower Hotel, and they employed Mr. and Mrs. John H. Neal to run it for them. J. C. Holbrook, the first to preach a sermon in Yosemite, writes of his stop with Mrs. Neal in 1859: “I secured a bed, such as it was, for my wife, in a rough board shanty occupied by a family that had arrived a few days before to keep a sort of tavern, the woman being the only one within fifty or sixty miles of the place. For myself, a bed of shavings and a blanket under the branches of some trees formed my resting place.”

A London parson in his To San Francisco and Back, of the late ’sixties, offers the following description of his visit to this earliest of Yosemite hotels:

There are in it [the valley] two hotels, as they call themselves, but the accommodation is very rough. When G——— and I were shown to our bedroom the first night we found that it consisted of a quarter of a shed screened off by split planks, which rose about eight or ten feet from the ground, and enabled us to hear everything that went on in the other “rooms.” which were simply stalls in the same shed. Ours had no window, but we could see the stars through the roof. The door, opening out into the forest, was fastened with cow-hinges of skin with the hair on, and a little leather strap which hooked on to a nail. We boasted a rough, gaping floor, but several of the other bedrooms were only strewed with branches of arbor vitae. As a grizzly bear had lately been seen wandering about a few hundred yards from our “hotel,” we took the precaution of putting our revolvers under our pillows. I dare say this was needless as the bears have mostly retired to the upper part of the valley, a few miles off, but it gave a finish to our toilet which had the charm of novelty. Next morning, however, seeing the keeper of the ranch with his six-shooter in his hand, and noticing that it was heavily loaded, I asked him why he used so much powder. “Oh,” said he, “I’ve loaded it for bears.”

At first G——— and I were the only visitors at this house, but several were at the other one about half a mile off, and more were soon expected.

Cunningham, A. G. Black, P. Longhurst, and G. F. Leidig all took their turn at operating the crude establishment. It was under the management of Black when Clarence King arrived on his pioneer trip with the Geological Survey of California, and one Longhurst apparently even then anticipated future proprietorship by engaging in guiding its guests about the valley. King describes Longhurst as “a weather-beaten round-the-worlder, whose function in the party was to tell yarns, sing songs, and feed the inner man.” His account, in Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada, continues:

We had chosen, as the head-quarters of the survey, two little cabins under the pine-trees near Black’s Hotel. [Black was then owner of the Lower Hotel.] They were central; they offered us a shelter; and from their doors, which opened almost upon the Merced itself, we obtained a most delightful sunrise view of the Yosemite.

Next morning, in spite of early outcries from Longhurst, and a warning solo of his performed with spoon and fry-pan, we lay in our comfortable blankets pretending to enjoy the effect of sunrise light upon the Yosemite cliff and fall, all of us unwilling to own that we were tired out and needed rest. Breakfast had waited an hour or more when we got a little weary of beds and yielded to the temptation of appetite.

A family of Indians, consisting of two huge girls and their parents, sat silently waiting for us to commence, and, after we had begun, watched every mouthful from the moment we got it successfully impaled upon the camp forks, a cloud darkening their faces as it disappeared forever down our throats.

But we quite lost our spectators when Longhurst came upon the boards as a flapjack-frier, a rÔle to which he bent his whole intelligence, and with entire success. Scorning such vulgar accomplishment as turning the cake over in mid-air, he slung it boldly up, turning it three times, ostentatiously greasing the pan with a fine centrifugal movement, and catching the flapjack as it fluttered down, and spanked it upon the hot coals with a touch at once graceful and masterly.

I failed to enjoy these products, feeling as if I were breakfasting in sacrilege upon works of art. Not so our Indian friends, who wrestled affectionately for frequent unfortunate cakes which would dodge Longhurst and fall into the ashes.

In 1869 A. G. Black tore down the Lower Hotel and on its site constructed the rambling building which became known as “Black’s.”

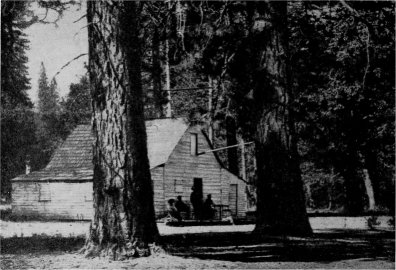

Prior to their interest in the Lower Hotel, S. M. Cunningham and Buck Beardsley had essayed to start a store and tent shelter on the later site of the Cedar Cottage. Cunningham, of later Big Tree fame, dropped this venture; so Beardsley united with G. Hite and in the fall of 1857 began the preparation of the timbers which made the frame of the Cedar Cottage. Mechanical sawmills had not yet been brought so far into the wilderness, and the partners whipsawed and hewed every plank, rafter, and joist in the building. It was ready for occupancy in May, 1859.

The proprietors of the Upper Hotel fared none too well in the returns forthcoming from guests. Ownership changed hands a number of times, and business dwindled to a point of absolute suspension. In 1864 it was possible for J. M. Hutchings to purchase the building and the land claim adjoining for a very nominal price. At this time the proposed state park was being widely talked of, and, as a matter of fact, Hutchings stepped into the ownership of the Upper Hotel property but a few months before the Yosemite Valley was removed from the public domain and granted to the state to be “inalienable for all time.” Mr. Hutchings was, and is to this day, sharply criticized by some citizens for his presumption in purchasing public lands that had not been officially surveyed. Whatever may have been his legal claim, it must be admitted that his was the moral right to expect compensation for the expenditure of thousands of dollars for physical improvements made upon his Yosemite property.

Hutchings brought his family to the Upper Hotel in 1864 and assumed a proprietorship that awakened lengthy comments

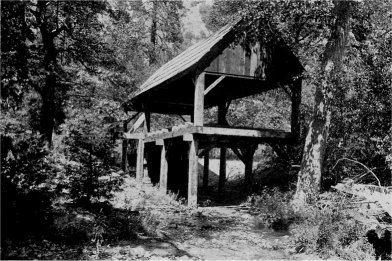

By George Fiske Mill Built by John Muir in 1869 |

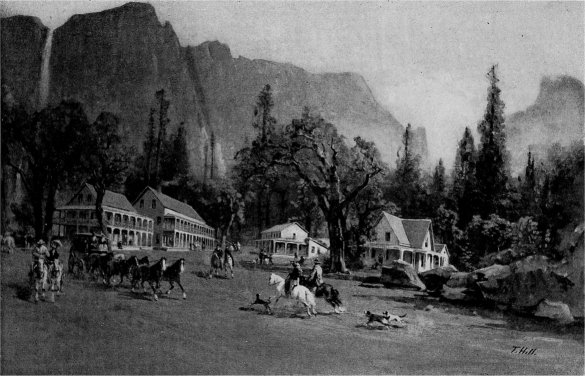

By Thomas Hill Sentinel Hotel (left background), 1876 to 1938 |

By Thomas Hill Sentinel Hotel (left background), 1876 to 1938 |

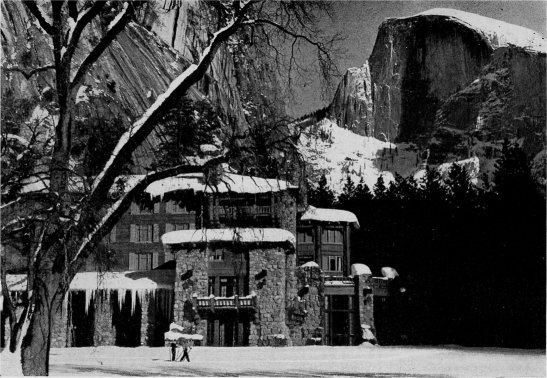

By D. R. Brower The Ahwahnee Hotel, 1927 to date |

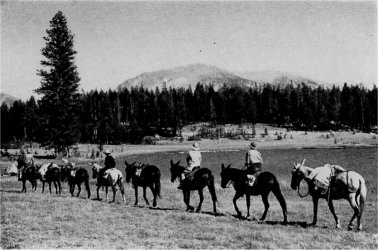

By Ansel Adams Saddle Trip on a High Sierra Trail |

By Ansel Adams Merced Lake High Sierra Camp, 1916 to date |

Charles Loring Brace visited Yosemite a few years after Hutchings became a local character there. He stopped at the Hutchings House and later wrote about his experience:

One of the jokes current in the Valley is to carefully warn the traveler, before coming to this hotel, “not to leave his bed-room door unlocked, as there are thieves about!” On retiring to his room for the night, he discovers to his amazement, that his door is a sheet, and his partition from the adjoining sleeping-chamber also a cotton cloth. The curtain-lectures and bed-room conversations conducted under these circumstances, it may be judged, are discreet. The house, however, is clean, and the table excellent; and Hutchings himself, enough of a character alone to make up for innumerable deficiencies. He is one of the original pioneers of the Valley, and at the same time is a man of considerable literary abilities, and a poet. He has written a very creditable guidebook on the Canyon. No one could have a finer appreciation of the points of beauty, and the most characteristic scenes of the Valley. He is a “Guide” in the highest sense, and loves the wonderful region which he shows yearly to strangers from every quarter of the world. But, unfortunately, he is also hotel-keeper, waiter, and cook—employments requiring a good deal of close, practical attention, as earthly life is arranged. Thus we come down, very hungry, to a delicious breakfast of fresh trout, venison, and great pans of garden strawberries; but, unfortunately, there are no knives and forks. A romantic young lady asks, in an unlucky moment, about the best point of view for the Yosemite Fall. “Madam, there is but one; you must get close to the Upper Fall, just above the mist of the lower, and there you will see a horizontal rainbow beneath your feet, and the most exquisite—”

Here a strong-minded lady, whose politeness is at an end, “But here, Hutchings, we have no knives and forks!” “Oh, beg a thousand pardons, madam!” and he rushes off; but meeting his wife on the way, she gives him coffee for the English party, and he forgets us entirely, and we get up good-naturedly and search out the implements ourselves. Again, from an amiable lady, “Please, Mr. Hutchings, another cup of coffee!” “Certainly, Madam!” When the English lady from Calcutta asks him about some wild flowers, he goes off in a botanical and poetical disquisition, and in his abstraction brings the other lady, with great eagerness, a glass of water. Sometimes sugar is handed you instead of salt for the trout, or cold water is poured into your coffee; but none of the ladies mind, for our landlord is as handsome as he is obliging, and really full of information.

Maria Teresa Longworth, known as Therese Yelverton, Viscountess Avonmore, visited Yosemite in 1870, where she wrote Zanita: A Tale of the Yosemite, published in 1872. She made the Hutchings’ entourage a part of her melodrama, and Florence, eldest daughter of the Hutchingses, was the heroine, “Zanita.” John Muir, of whom in real life the Viscountess was enamored, was the hero, “Kenmuir.” A good analysis of Yelverton’s relationships, actual and fictional, with the Hutchings family and the other pioneer residents of the valley is contained in Linnie Marsh Wolfe’s great book, Son of the Wilderness.

Not all of the Hutchings House features were within its walls. J. D. Caton, who availed himself of the Hutchings hospitality in 1870, “walked over to the foot of the Yosemite Falls and lingered by the way to pick a market basket full of enormous strawberries in Hutchings’ garden.” One of the first acts of the homesteaders was to plant an orchard and cultivate the above-mentioned strawberry patch. The strawberries long ago disappeared, but many of the one hundred and fifty apple trees still thrive and provide fruit for permanent Yosemite residents.

During his regime of ownership, Hutchings added Rock Cottage, Oak Cottage, and River Cottage to his caravansary. In 1844 the state legislature appropriated $60,000 to extinguish all private claims in Yosemite Valley, and the Hutchings interests were adjudged to be entitled to $24,000.

Coulter and Murphy then became the proprietors of the old Hutchings group and in 1876 they built the Sentinel Hotel. Their period of management was brief, and the entire property passed to J. K. Barnard in 1877, who for seventeen years maintained it as the Yosemite Falls Hotel.1 [ 1See Fannie Crippen Jones, “The Barnards in Yosemite,” MS in Yosemite Museum. ] This unit among the pioneer hostelries was torn down in 1938-1940.

Galen Clark accompanied one of the 1855 Yosemite-bound parties that had been inspired by Hutchings, when that pioneer related his experiences in Mariposa. Upon his first trip to the valley over the old Indian trail from Mariposa, he recognized in the meadows on the South Fork of the Merced a most promising place of abode. His health had been impaired in the gold camps; he had, in fact, been told by a physician that he could live but a short time. The lovely vale of the Nuchu Indians offered solace, and in April of 1857 he settled there on the site of the camp occupied by the Mariposa Battalion in 1851. Nowhere in his writings does Clark intimate that he expected to be overtaken by early death at the time of his homesteading. Rather we may believe that it was with foresight and careful plan that he erected his cabin beside the new trail of the sight-seer and prepared to accommodate those saddle-weary pilgrims who mounted horses at Mariposa and made their first stop with him en route to the new mecca.

His first cabin was crude. A rough pine table surrounded by three-legged stools facilitated his homely service. As the number of visitors increased, Clark enlarged his ranch house. When ten years of his pioneer hotel keeping had passed, Charles Loring Brace was among his visitors. Brace writes:

After fourteen miles—an easy ride—we all reached Clark’s Ranch at a late hour, ready for supper and bed.

This ranch is a long, rambling, low house, built under enormous sugar-pines, where travelers find excellent quarters and rest in their journey to the Valley. Clark himself is evidently a character; one of those men one frequently meets in California—the modern anchorite—a hater of civilization and a lover of the forest—handsome, thoughtful, interesting, and slovenly. In his cabin were some of the choicest modern books and scientific surveys; the walls were lined with beautiful photographs of the Yosemite; he knew more than any of his guests of the fauna, flora, and geology of the State; he conversed well on any subject, and was at once philosopher, savant, chambermaid, cook, and landlord.

From the scores of books written by early Yosemite visitors, one might extract a great compendium of remarks on Clark and his ranch. The proprietor, like the Grizzly Giant, was impressive. He was invariably remembered by his guests. They wrote of his generous hospitality, his simplicity, kindness, honesty, wit, wisdom, and unselfish devotion to the mountains he loved. Had they known, they might have written that he gave too freely of all his mental and physical assets and that as a businessman he was not a success. The season of 1870 found the ownership of his ranch divided with Edwin Moore.

Moore assumed general management, and Clark’s became known as “Clark and Moore’s.” The ladies of Moore’s family introduced a new element in the hospitality of the place, and for a few years it assumed an aspect of new ambition. Extensive improvements, however, resulted in foreclosure of mortgages, and the firm of Washburn, Coffman, and Chapman secured ownership in 1875 and changed the name to “Wawona.”

A. P. Vivian stopped at Wawona in January, 1878, and wrote:

Although still called a “ranche,” this establishment has long ceased to be mainly concerned with agriculture. Clark himself exists no longer, at any rate in this locality; that individual sold his interests some years ago to Messrs. Washburn, who “’run the stage,” and are now the “bosses of the route” between this and Merced. The ranche is now a small but comfortable and roomy inn, and during the tourists’ season is filled to overflowing.

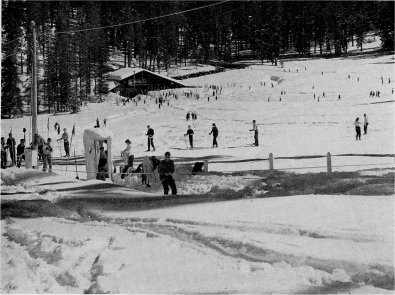

By Ralph Anderson, NPS Badger Pass Ski House |

By Ralph Anderson, NPS Ski Patrol at Work |

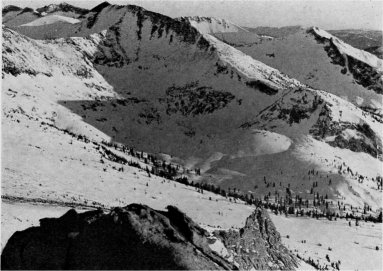

By D. R. Brower Winter in the Yosemite High Sierra: Clark Range |

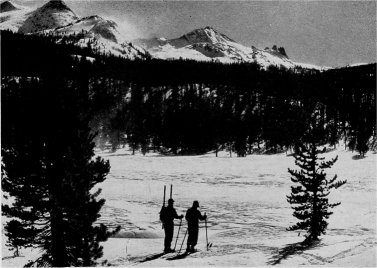

By Ralph Anderson, NPS Snow Gaugers Entering Tuolumne Meadows |

Besides having constructed the twenty-five miles of capital road hence into the Yosemite Valley, Messrs. Washburn are again showing their enterprise by making a road direct to Merced, the object of which is to save thirty miles over the present Mariposa route.

The Yosemite Park and Curry Company now owns and operates Wawona. It has become one of the largest and most favorably known family resorts in the Sierra Nevada and retains some of the flavor of its earlier years.

A. G. Black was a pioneer of the Coulterville region. In the late ’fifties, he resided at Bull Creek on the Coulterville trail. Visitors who entered the valley from the north during the first years of tourist, travel have left a few records of stops made at the “Black’s” of that place. The “Black’s” of Yosemite Valley did not come into existence until the advent of the ’sixties, when Mrs. Black is reported to have purchased the old Lower Hotel. In 1869 this first structure was torn down, and an elongated shedlike structure built on its site, near the foot of the present Four-Mile Trail to Glacier Point. This was the “Black’s” that for nineteen years served a goodly number of Yosemite tourists. In 1888, after the opening of the Stoneman House, there was among the commissioners “a unanimity of feeling that the old shanties and other architectural bric-a-brac, that had long done service for hotels and stables, and the like, should be torn down.” Black’s Hotel was accordingly removed in the fall of 1888, and the lumber from its sagging walls went into the construction of the “Kenneyville” property, which stood on the present site of the Ahwahnee Hotel.

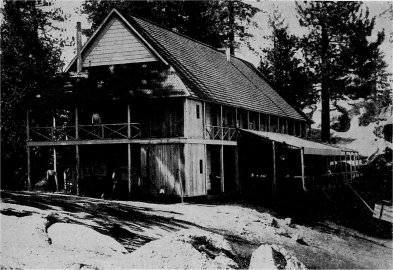

The family of George F. Leidig arrived in Yosemite Valley in 1866. For a time the old Lower Hotel was in their charge, but, when its owner, A. G. Black, assumed its management personally, the Leidigs secured rights to build for themselves. They selected a site just west of the old establishment and constructed a two-story building to become known as Leidig’s. This was in 1869. Charles T. Leidig, the first white boy to be born in the valley, was born in the spring of that year.

Mrs. Leidig’s ability as a cook was quickly noted by visitors, and, no doubt, the popularity of her table did much to draw patrons. Many are the printed comments in the contemporary publications of her guests. Here is an example:

Leidig’s is the best place in the line of hotels. Mrs. L—— attends to the cooking in person; the results are that the food is well cooked and intelligently served. There is not the variety to be obtained here as in places more accessible to market. After traveling a few months in California, a person is liable to think less of variety and more of quality. At this place the beds are cleanly and wholesome, although consisting of pulu mattresses placed upon slat bedsteads. This house stands in the shadow of Sentinel Rock, and faces the great Yosemite Fall; is surrounded with porches, making a pleasant place to sit and contemplate the magnificence of the commanding scenery. (From Caroline M. Churchill, 1876.)

When A. P. Vivian continued on to Yosemite in January of 1878, he found the Leidig family in the valley and commented as follows on his winter reception:

Our host was glad enough to see us, for tourists are very scarce commodities at this time of the year, and he determined to celebrate our arrival by exploding a dynamite cartridge, that we might at the same time enjoy the grand echoes. These were doubtless extraordinary, but I am free to confess I would rather have gone away without hearing them than have experienced the anxiety of mind, and real risk to body, which preceded the pleasure.

Leidig’s, with Black’s, was torn down after the Stoneman House provided more fitting accommodations. The little chapel which had been built near these old hotels in 1879 was moved to its present site in the Old Village. In 1928 the picturesque old well platform and crane, which had marked the Leidig site, was destroyed. Only a group of locust trees now indicates where this center of pioneer activity existed.

But the wonder—among the buildings of Yosemite—is the “Cosmopolitan,” containing saloon, billiard hall, bathing rooms, and barber-shop, established and kept by Mr. C. E. Smith. Everything in it was transported twenty miles on mules; mirrors full-length, pyramids of elaborate glassware, costly service, the finest of cues and tables, reading-room handsomely furnished and supplied with the latest from Eastern cities, and baths with unexceptionable surroundings, attest the nerve and energy of the projector. It is a perfect gem. The end of the wagon-road was twenty miles away when the enterprise began, and yet such skill was used in mule-packing that not an article was broken. I have not seen a finer place of resort, for its size. The arrangements for living are such that one could spend the summer there delightfully, and we found several tourists who remained for weeks.

The foregoing from J. H. Beadle is but one of scores of enthusiastic outbursts from amazed tourists who wrote of their Yosemite experiences. To say that C. E. Smith figured in early Yosemite affairs is hardly expressive. His baths, his drinks, and the various unexpected comforts provided by his Cosmopolitan left lasting impressions that vied with El Capitan when it came to securing space in books written by visitors. The ladies exclaimed over the cleanliness of the bathtubs; a profusion of towels, fine and coarse; delicate toilet soaps, bay rum, Florida water, arnica, court plaster; needles, thread, and buttons; and late copies of the Alta and the Bulletin for fresh “bustles.” The men found joy in “a running accompaniment of ‘brandy-cocktails,’ ‘gin-slings,’ ‘barber’s poles,’ ‘eye-openers,’ ‘mint-julep,’ ‘Samson with the hair on,’ ‘corpse-revivers,’ ‘rattlesnakes,’ and other potent combinations.”

The Cosmopolitan boasted of a certain Grand Register, a foot in thickness, morocco-bound, and mounted with silver. Within it were the autographs and comments of thousands of visitors both great and lowly. The relic is now a part of the Yosemite Museum collection.2 [ 1 See Harwell, C. A., Yosemite Nature Notes, 1933, Vol. XII, No. 1. ]

Tommy Hall, the pioneer barber of Yosemite, found sumptuous quarters in the Cosmopolitan. The old building continued to house a barber shop until it was destroyed by fire on December 8, 1932.

For fifteen years after the coming of visitors, the wonders of the Merced Canyon above Happy Isles were accessible only to those hardy mountaineers who could scramble through the boulder-strewn gorge without the advantage of a true trail. In 1869-70 one Albert Snow completed a horse trail front Yosemite Valley to the flat between Vernal and Nevada falls, and there opened a mountain chalet, which was to be known as “La Casa Nevada.” The popularity of the saddle trip to the two great falls of the Merced was immediate, and the pioneer trail builder, John Conway, extended the trail from Snow’s to Little Yosemite Valley the next year. It then was usual for all tourists to ascend the Merced Canyon to La Casa Nevada and Little Yosemite. Some hikers undertook the trip from Little Yosemite to Glacier Point, but another fifteen years were to elapse before Glacier Point was made accessible by a truly good horse trail from Nevada Fall.

Snow’s was opened on April 28, 1870. One of the prized possessions of the Yosemite Museum is a register from this hostelry, which dates from the opening to 1875. Upon its foxed pages appear thousands of registrations and numerous comments of more than passing interest. Among these is a very interesting two-page manuscript by John Muir, describing an 1874 trip to Snow’s via Glacier Point and the Illilouette. P. A. H. Laurence [Editor’s note: James Henry Laurence—dea], once editor of the Mariposa Gazette, contributed to its value by inscribing within it an account of his visit to Yosemite Valley in 1855, years before the chalet was built.

A party with N. H. Davis, United States Inspector General, commented upon their destination and added: “This party defers further remarks until some further examinations are made.” Under the date of the original entry is a significant second autograph by a member of the General’s party: “A preliminary examination develops an abundance of mountain dew.”

A great pile of broken containers, which had once held the “mountain dew,” is about the only remnant of La Casa Nevada which may be viewed by present-day visitors, for the chalet was destroyed by fire in the early ’nineties.

Another pioneer hotel is represented in the Yosemite Museum collections by a register.3 [ 3 See Taylor, Mrs. H. J., Yosemite Nature Notes (1929). ] It was known as the Mountain View House and occupied a strategic spot on the old horse trail from Clark’s to Yosemite Valley. Its site is known to present-day visitors as Peregoy Meadows, and the remains of the log building now repose quite as they fell many years ago. The hospitality of its keepers, Mr. and Mrs. Charles E. Peregoy, was utilized by those travelers who, coming from Clark’s, took lunch there, or by those who departed from the valley via Glacier Point and made it an overnight stopping place.

The Mountain View House register indicates that guests were entertained as early as the fall of 1869. It was not, however, until the spring of 1870 that the little resort made a bid for patronage. Its capacity for overnight accommodation was sixteen; so it is not surprising that a number of writers of the ’seventies were forced to record, in their published Yosemite memoirs, that they arrived late and sat around the kitchen stove all night. In June of 1872, fifty-six tourists were overtaken by a snowstorm in the neighborhood of Peregoy’s. It is to be surmised that on that night even the little kitchen did not accommodate the overflow.

The construction of the Wawona road in 1875 revised the route of all Yosemite travel south of the Merced. Peregoy’s was left far from the line of travel and no longer functioned in the scheme of Yosemite resorts.

By 1878, the demand for recognition of private camping parties introduced the idea of public camp grounds in Yosemite. Large numbers of visitors were bringing their own conveyances and camping equipment so as to be independent of the hostelries. The commissioners set aside a part of the old Lamon property in the vicinity of the present Ahwahnee Hotel as the grounds upon which to accommodate the new class of visitors. Mr. A. Harris was granted the right to administer to the wants of the campers. He grew fodder for their animals, offered stable facilities, sold provisions, and rented equipment. The Harris Camp Ground was the forerunner of the present-day housekeeping camps and public auto camps, which accommodate, by far, the greater number of Yosemite visitors.

An exceedingly interesting register, kept for the comments of campers of that day, was recently presented to the Yosemite Museum by the descendants of Harris. For ten years Yosemite campers recorded their ideas of Yosemite, its management, and particularly the kindness of Harris, upon its pages. The following is representative:

Yosemite Valley,

Tuesday, July 10th, 1880

We have tented in the Valley and been contented too.

So would like to add a chapter to this bible for review

Of campers who come hither for study or for fun

In this Valley—of God’s building the grandest ’neath the sun.

When you come into the Valley—for information go

To the owner of this Record, and directly he will show

You where to go, and how to go, and what to see when there

And will sell you all things needful, at prices that are fair.

Like Moses in the wilderness, he’ll furnish food and drink

For all the tribes that come to him—cheaper than you’d think.

His bread is not from Heaven—but San Francisco Bay

And that is next thing to it—so San Franciscans say.

The water that he gives you—running through granite rock

Is the same as that which Moses gave his wonder-stricken flock.

If you ask him where to angle—he’ll tell you—on the sly

Down in the Indian Camp—with silver hook and fly.

In a word this Mr. Harris is a proper kind of man,

And as a friend to campers in the Valley—leads the van.

Wm. B. Lake

Fred W. Lake}

} San FranciscoE. D. Lake

Nat Webb}

} SacramentoIf the reader thinks this poetry—don’t judge me by the style,

For ’t is the kind that rhymsters make to peddle by the mile.W B L

It may be said that from the Harris service grew the idea of camp rental, which was first practiced by the commissioners in 1898 and is now a recognized business of the housekeeping-camps department of the present operators in the park.

After the construction of Snow’s trail to Little Yosemite in 1871, some good mountaineers made the Glacier Point trip via Little Yosemite and the Illilouette basin. Prior to this time, J. M. Hutchings had been guiding parties of hikers to the famous Point over a most hazardous trail, which he had blazed up the Ledge and through the Chimney. Occasional references to a shack at Glacier Point indicate that Peregoy had made some attempt to locate there about the same time that his Mountain View House of Peregoy Meadows was opened for business. However, the real claim for Glacier Point patronage came from one James McCauley, who in 1870-1871 met the expense of building a horse trail from Black’s and Leidig’s over a four-mile route up the 3,200-foot cliff to the famous vantage point. This new route was at first a toll trail. For sixty years it has been climbed and descended by countless thousands of riders and hikers. It has been known as the Four-Mile Trail for more than half a century, and it was not until 1929 that its grades, surveyed and built by John Conway, were changed by more skilled engineers.

It is likely that McCauley, owner of the Four-Mile Trail, made use of the insufficient little building on Glacier Point while his trail was in the making. Few records regarding the “shack” or his later Mountain House are to be found, but Lady C. F. Gordon-Cumming wrote on the tenth of May, 1878: “The snow on the upper trail [Four-Mile] had been cleared by men who are building a rest-house on the summit.” After arriving at Glacier Point, she records: “The cold breeze was so biting that we were thankful to take refuge, with our luncheon-basket, in the newly built wooden house.” Later, “On our way down through the snow-cuttings, we had rather an awkward meeting with a long file of mules heavily laden with furniture— or rather, portions of furniture—for the new house.”

It is believed that the first firefall from Glacier Point was the work of James McCauley in 1871 or 1872. He sold his trail to the state. His Mountain House was operated on a lease basis from the commissioners. One of his visitors of the early ’eighties was Derrick Dodd, who concocted something of a classic in the way of Glacier Point stories. It is too good to pass into oblivion.

As a part of the usual programme, we experimented as to the time taken by different objects in reaching the bottom of the cliff. An ordinary stone tossed over remained in sight an incredibly long time, but finally vanished somewhere about the middle distance. A handkerchief with a stone tied in the corner, was visible perhaps a thousand feet deeper; but even an empty box, watched by a field-glass, could not be traced to its concussion with the Valley floor. Finally, the landlord appeared on the scene, carrying an antique hen under his arm. This, in spite of the terrified ejaculations and entreaties of the ladies, he deliberately threw over the cliff’s edge. A rooster might have gone thus to his doom in stoic silence, but the sex of this unfortunate bird asserted itself the moment it started on its awful journey into space. With an ear-piercing cackle that gradually grew fainter as it fell, the poor creature shot downward; now beating the air with ineffectual wings, and now frantically clawing at the very wind, that slanted her first this way and then that: thus the hapless fowl shot down, down, until it became a mere fluff of feathers no larger than a quail. Then it dwindled to a wren’s size, disappeared, then again dotted the sight a moment as a pin’s point, and then—it was gone!

After drawing a long breath all round, the women folks pitched into the hen’s owner with redoubled zest. But the genial McCauley shook his head knowingly, and replied:

“Don’t be alarmed about that chicken, ladies. She’s used to it. She goes over that cliff every day during the season.”

And, sure enough, on our road back we met the old hen about half up the trail, calmly picking her way home!

In 1882, the Glacier Point road was built. Traffic to the Mountain House was, of course, doubled by the coming of those who would not walk or ride a horse up steep trails. Glacier Point trails did not fall into disuse, however. On the contrary, attempts were made to make them more attractive. Anderson’s Trail from Happy Isles to Vernal Fall was constructed at great loss to its builder in 1882. The present Eleven-Mile Trail from Nevada Fall to Glacier Point was built in 1885. In spite of the variety of routes offered, it was planned as early as 1887 to provide a passenger lift to the famous vantage-point. The plan progressed as far as the making of a preliminary survey. Accommodations at the point remained unchanged until 1917, when the Glacier Point Hotel was built by the Desmond Park Service Company adjacent to the Mountain House. The two structures function as a unit of the Yosemite Park and Curry Company operation.

The Degnan concession in the “Old Village” is not and never was a hotel or lodge. However, it has catered to Yosemite tourists since 1884 and is the oldest business in the park. John Degnan, an Irishman, built his first Yosemite cabin on the site of the present Degnan store. Soon thereafter, on the occasion of a spring meeting of the Yosemite Valley Commissioners, of which the governor of the state was a member, Mr. Degnan appeared before the managing body to obtain the privilege of building a suitable home. The board listened to his plea, and the Governor observed, “He seems to be the kind of man we want as an all-year resident—one who will take care of the place when it needs care.” Mr. Degnan, in an interview with a National Park Service official in 1941, stated, “After that meeting the Commissioners came over to my cabin, and the Governor then assigned to me the land which I now occupy, extending from the road to the cliff.”

Mrs. Degnan, who was a party to all of Mr. Degnan’s pioneering in Yosemite Valley, met the tourists’ demand for bread. Gradually, her bakery expanded until her ovens could turn out one hundred loaves at a baking. The business and the home grew as did the Degnan family. Mary Ellen Degnan, one of the several children born to Mr. and Mrs. Degnan, now manages the modern store and restaurant which evolved from the pioneer venture.

The record of John Degnan’s activities in Yosemite National Park stands as ample testimony to the accuracy of the governor’s appraisal, “He seems to be the kind of man we want.” He was a respected party to much of the early physical improvement in and about the valley and to the general growth and development of facilities and services.

Mrs. Degnan died Dec. 17, 1940, and Mr. Degnan’s death occurred on Feb. 27, 1943.

The demand for more pretentious accommodations than those afforded by the pioneer hotels of Yosemite was met in 1887, when the state built a four-story structure that would accommodate about 150 guests. The legislature in 1885 appropriated $40,000 to be expended on this building. Another $5,000 was secured for water supply and furniture. A site near the present Camp Curry garage was selected, and the building contract let to Carle, Croly, and Abernethy. Upon its completion J. J. Cook, who had been managing Black’s Hotel, was placed in charge.

The bulky structure was not beautiful architecturally, and the first few years of its existence demonstrated that its design was faulty. In 1896 the Stoneman House burned to the ground.

Mr. and Mrs. D. A. Curry originated an idea in tourist service which rather revolutionized the scheme of hostelry operation in Yosemite and other national parks. The Currys came to Yosemite in 1899. They were teachers who had turned their summer vacations into profitable management of Western camping tours in such localities as Yellowstone National Park. Their first venture in Yosemite involved use of seven tents and employment of one paid woman cook. The services of several college students were secured in return for summer expenses. The site chosen for that first camp is the area occupied by Camp Curry.

Success of the hotel-camp plan was immediately apparent. The first year 292 people registered at the resort. However, success was not attained without striving. The camp was dependent upon freight-wagon service requiring two weeks to make the round trip to Merced. Sometimes even this service failed.

Informal hospitality has always characterized Camp Curry. Popular campfire entertainments have been a feature from me beginning. In one of the first summers in Yosemite, D. A. Curry revived the firefall,4 [ 4 Beatty, M. E. “History of the Firefall” Yosemite Nature Notes (1934), pp. 41-43; and Yosemite Park and Curry Co., 1940, The Firefall, Explanation and History, Yosemite National Park, pp. 1-5.] which it is presumed originated with James McCauley, of the Mountain House. Employees from Camp Curry were occasionally sent to Glacier Point to build a fire and push it off for a special party. This was done more and more frequently, until it became a nightly occurrence. Mr. Curry’s “Hello,” his “All’s well,” and “Farewell,” delivered with remarkable volume, won for him the appellation, “The Stentor of Yosemite.”

The coming of the Yosemite Valley Railroad in 1907 gave a powerful new impetus to the growth of Camp Curry. Automobile travel, of course, provided the climax. In 1915 the camp provided accommodations for one thousand visitors. Today, it maintains nearly 500 tents and 200 bungalow and cabin rooms.

The successful operations of the Curry business induced would-be competition. Camp Yosemite, later known as Camp Lost Arrow, was started in 1901 near the foot of Yosemite Falls. It continued to function until 1915. Camp Ahwahnee, at the foot of the Four-Mile Trail, was established in 1908 and continued for seven years. The Desmond Park Service Company secured a twenty-year concession to operate camps, stores, and transportation service in 1915. This company purchased the assets of the Sentinel Hotel, Camp Lost Arrow, and Camp Ahwahnee. The two camps were discontinued, and a new venture made in the present Yosemite Lodge. The Desmond Company prevailed until 1920, when reorganization took place, and it became the Yosemite National Park Company.

The Curry Camping Company maintained its substantial position through all of the years of varying fortunes of its less substantial contemporaries. In 1925, the Yosemite Park and Curry Company was formed by the consolidation of the Curry Company and the Yosemite National Park Company. The new organization has contracted with the government to perform all services demanded by the public in the park. Some 1,250 people are employed during the summer months, and the investment in tourist facilities totals $5,500,000.

David A. Curry did not live to witness the realization of all his plans. However, prior to his death in 1917, the march of progress had so advanced as to make evident the place of leadership the Curry operation was to maintain. “Mother” Curry, as “Manager Emeritus,” still devotes personal attention to the business of the pioneer hotel-camp but the active management is in the hands of persons trained by her and her daughter, Mary Curry Tresidder. Her son-in-law, Dr. Donald B. Tresidder, until 1943 actively managed the operations and still retains the presidency of the extensive Yosemite Park and Curry Company, which has grown from the modest start made in 1899.

The Yosemite National Park Company in 1920 established a tent camp in the upper section of the Mariposa Grove, which consisted of a rustic central building constructed around the base of the tree, Montana, and a group of cabins and tents. The camp persisted in this form until 1932, when it was razed by the Yosemite Park and Curry Company, and a new lodge was built near Sunset Point in the Grove. In its design the new building reflects the charm of pioneer structures of the Sierra Nevada.

In 1923, Superintendent Lewis advocated the creation of a service that would enable the hiker to enjoy the wonders of the Yosemite high country and yet be free from the irksome load of blankets and food necessary to the success of a trip away from the established centers of the park. T. E. Farrow, of the Yosemite Park Company, projected tentative plans for a series of “hikers’ camps,” and in the fall of 1923 I was dispatched on a journey of reconnaissance for the purpose of locating camp sites in the rugged country drained by the headwaters of the Merced and Tuolumne. The sites advocated were Little Yosemite, Merced Lake,* Boothe Lake, the Lyell Fork (Mount Lyell), Tuolumne Meadows,* Glen Aulin, and Tenaya Lake.* In 1924, these sites, with the exception of Lyell Fork and Glen Aulin, were occupied by simple camps, consisting of a mess and cook tent, a dormitory tent for women, and a dormitory tent for men. Attendants and cooks were employed for each establishment. With two exceptions, the camps were removed from roads, and equipment and supplies were of necessity packed in on mules. Yet it was possible to offer the facilities of these high mountain resorts at a very low price, and it became apparent that saddle parties, as well as hikers, would take advantage of them. Consequently they have become known as High Sierra Camps.

*Camps at these spots first were established in the days of the Desmond Park Service Company, 1916-1918.

The camp beside the White Cascade at Glen Aulin was established in 1927 and has been very popular. In 1938, the Tenaya Lake Camp was moved to a beautiful location in a grove of hemlocks on May Lake, just east of Mount Hoffmann. New trails were built to make this spot more readily accessible from the Snow Creek Trail and from Glen Aulin. The Boothe Lake Camp, after a few years of operation, was abandoned in favor of a new camp near the junction of the Vogelsang, Rafferty Creek, and Lyell Fork trails. In 1940, this camp was rebuilt on the banks of Fletcher Creek. The Tuolumne Meadows Lodge is now the only one of these camps situated on a road. Each camp has a setting of a distinctive mountain character on lake or stream. All the camps represent a joint effort on the part of the National Park Service and the concessionaire to encourage and assist travel beyond the roads, where the visitor may appreciate the wild values of the park which he can hardly observe from the highways.

The Yosemite Park and Curry Company opened the Ahwahnee in 1927. Its interior has received quite as much study as has its exterior architectural values.

California Indian patterns have been used throughout the hotel in many ways. In the lobby, six great figures, set in multiple borders, rendered in mosaic, give color and interest to the floor. In the downstairs corridor and the dining room, other borders and simpler Indian motifs are rendered in acid-etched cement. Painted Indian ornaments play a number of different roles in the building.

In the main lounge the great beams have been related to the contents of the room with borders, spots, and panels of Indian motifs in the colors that appear in the rugs and furniture coverings, while the entire mantel end of the room serves as a bond between the ceiling and the floor with a composite of Indian figures built into one great architectural structure. At the top of each of the ten high windows is a panel of stained glass, each one different, the series forming a rhythmical frieze that bands the room. They are all composed of Indian patterns.

The arts of the whole world have been called together to give the Ahwahnee character and color. There are Colonial furniture, pottery, and textiles; furniture, cottons and linen, lights, and a clock from England; cottons from Norway; and irons from Flanders; more iron and furniture and fabrics from France; embroideries from Italy; rugs from Spain; designs from Greece and designs from Turkey; rugs, jars, and tiles, silks and cottons from Persia; more rugs from the Caucasus and tent strips from Turkestan; porcelains and paintings from China; the sturdy Temmoku ware from Japan; fabrics from Guatemala; terra cotta from Mexico, and so back to California, whence comes the basic motif of the whole, the Indian design.

On June 23,1943, the Ahwahnee Hotel was taken over by the United States Navy and operated as a hospital. It functioned as the Naval Special Hospital until its formal decommissioning on December 15, 1945, and 6,752 patients were treated, the greatest number at one time being 853. A large and varied naval staff was assigned to duty at the Ahwahnee, including officers, nurses, Waves, and enlisted men. Representatives of the American Red Cross, Veterans’ Administration, and the United States Employment Service also participated in the hospital program. The Ahwahnee as a hospital became an adequately equipped and functioning rehabilitation center, capable of handling full programs of physical training, occupational therapy, and educational work. The department of occupational therapy, especially, was recognized as outstanding among service hospitals. The program of rehabilitation extended to the out-of-doors, both summer and winter.

|

Next: East-side Mining • Contents • Previous: Explorers

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/one_hundred_years_in_yosemite/hotels.html