| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > 100 Years in Yosemite > Explorers >

Next: Hotels • Contents • Previous: Stagecoach Days

|

|

|

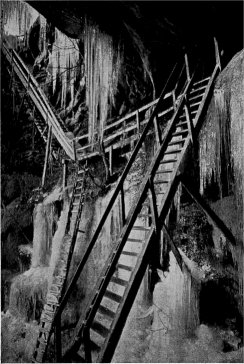

| Woodcut from the first edition (1931) |

The influx of travelers even in the days of horse trails and the stagecoach brought a demand to know more of the valley and the region as a whole. Maps were needed, and the desires of travelers for dependable information brought survey parties into the park. The first of these, the Geological Survey of California, was in Yosemite in the years 1863-1867. Josiah Dwight Whitney was director of the survey, and William H. Brewer, his principal assistant. A guidebook based upon their investigations was published in 1868. Most of the mapping was done by Clarence King, Charles F. Hoffmann, and James T. Gardiner. King was later to become the first director of the United States Geological Survey and to write a dramatized account of his adventures in Yosemite and the Sierra as one of the important contributions to the literature of the range, Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada. Later mountaineers have not always been able to find terrain hazards he described but they have enjoyed his story, admittedly written for an armchair audience, and have made due allowance for an aspect of greater severity that existed in the Sierra of his day.

A party of the Wheeler Survey, under George Montague Wheeler, in general charge of the Geographical Surveys west of the 100th Meridian, was in Yosemite in the late ’seventies and early ’eighties and in 1883 produced a large-scale topographic map of Yosemite Valley and vicinity. Lieut. M. M. Macomb was responsible for the Yosemite work.

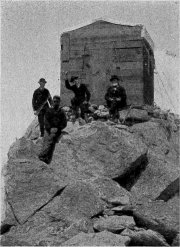

During July and August, of 1890, Professor George Davidson of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, together with his assistants, occupied the summit of Mount Conness for the purpose of closing a link in the main triangulation which connected with the transcontinental surveys.

Large instruments and much equipment had to be transported to the summit of the mountain by pack animals and upon the shoulders of men.

Astronomical observations were made at night, and during the daylight hours horizontal angles were measured on distant peaks in the Coast Ranges from which heliotropes were constantly showing toward Mount Conness. A small square wooden observatory, 8 by 8 feet, housed the 20-inch theodolite mounted upon a concrete pier. Sixteen twisted-wire cables fastened the observatory to the granite mountain top and kept it from being blown away.

The officers of the Coast and Geodetic Survey party under Professor Davidson were J. J. Gilbert, Isaac Winston, Fremont Morse, and Frank W. Edmonds.

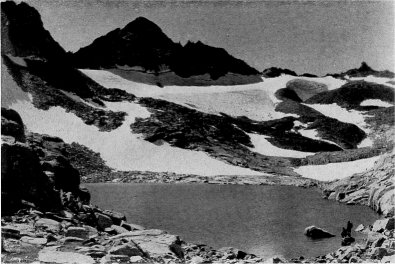

As a result of his own travels and surveys in the region, J. N. LeConte prepared a map of the Sierra adjacent to Yosemite and Hetch Hetchy valleys, which was published by the Sierra Club in 1893, and army officers in charge of park administration did much important map making in the 1890’s. The United States Geological Survey began its mapping of the region embraced within the present park in 1891 and completed the surveys in 1909. R. B. Marshall and H. E. L. Feusier surveyed the Yosemite, Dardanelles, and Mount Lyell sheets; A. H. Sylvester and George R. Davis, the Bridgeport Quadrangle. Operating as they did with limited funds, their efforts spread over a vast territory, and confronted with a short season, they inevitably made some errors on their maps. In correct editions of these maps some ridges, lakes, and canyons have been moved, but today’s travelers may still find lakes and glaciers which are not on the map, and may find a few of these features on the map but not on the ground. It is not the errors of Sierra mapmakers, however, but the measure of success they achieved, which is remarkable. In the higher reaches of the Sierra today it is extremely difficult to discover, after a particularly heavy winter, which snow field conceals a lake and which covers merely a meadow or an expanse of ice. Nor is the Sierra itself utterly static. At least two small lakes which formed behind dams of glacial moraine have disappeared recently when the dams were undermined.

Perhaps the ultimate in Yosemite mapping, from the geomorphologist’s point of view, is the Yosemite Valley Sheet, prepared by the United States Geological Survey in cooperation with the State of California. The map is of large scale, and the topography, the work of Franšois E. Matthes, is extremely accurate, giving it something of the quality of a relief map on a plane surface. Even the overhangs of the cliffs are depicted. The 1946 edition of this sheet falls short in that detail has been lost through the overprinting of topographical shading.

Considered for their practical guidance to the user of Yosemite trails, the U. S. Geological Survey maps of the back country are most important. The 700-odd miles of maintained trails which make much of the park accessible to the hiker and rider appear upon these topographical maps in true relationship to the physical features through which they pass. A useful guidebook covering the routes in and around Yosemite Valley, as well as many of the park trails south of the Tuolumne River, is the Illustrated Guide to Yosemite Valley, by Virginia and Ansel Adams. In this volume road and trail diagrams are stylized to impart, simply and directly, information on distances, altitudes, and relative positions. Walter A. Starr, Jr.’s Guide to the John Muir Trail and the High Sierra Region includes a section (Part I) on the trails of the Yosemite National Park region, and the map which accompanies it relates the high country trails to the road systems of both the east and west slopes. This guide, published by the Sierra Club, is kept up-to-date through the production of frequent editions.

Before the story of trail building within the national park is presented, it is worthwhile to review briefly the history of the approach routes outside the present limits of the park—the trails followed by the Indian fighters and miners.

Most of the early routes of the white man across the Yosemite Sierra and out of the valley itself followed Indian trails. The discovery of arrow points and knife blades on the slopes of some of the higher Yosemite peaks indicates that the Miwok Indians entered the high, rough country in pursuit of game. Their regularly established trade with the Monos also is a matter of record. Indian Canyon and the Vernal and Nevada falls gorge of the Merced provided two much used routes out of the valley to the east, and the Old Inspiration Point-Wawona -Fresno Flats-Coarse Gold route gave access to the foothill country to the west. There were other ancient routes on the valley walls accessible to an able-bodied Indian; however, except in emergency they probably found little use.

Walker, west-bound in 1833, followed the Miwok-Mono trail on the divide between the Merced and Tuolumne watersheds, having reached this divide, in all likelihood, via the maze of canyons formed by the tributaries of the East Walker River and the feeder streams of the Tuolumne River. White men in pursuit of eastward-fleeing Indians in 1851 penetrated to the Tenaya Lake basin, and one party in 1852 crossed to the east side via Bloody Canyon, as already described. This party returned to the San Joaquin on a branch of the Mono Trail which crossed Cathedral Pass, thence into Little Yosemite Valley, Mono Meadows, Peregoy Meadows, and Wawona. In all these travels definite trails of the aborigines could be followed even though many parts of the routes were buried in snow.

In the foothill region west of the park ancient Indian paths enabled gold seekers to reach much of the terrain in which they were interested. Barrett and Gifford (1933, p. 128) report that a Mr. Woods discovered gold on Woods Creek near the present Jamestown, Tuolumne County, in June, 1848, several months before the general rush of miners into the territory of the Southern Miwok. In this locality Indian trails connected the several rancherias near the present town, Sonora, with similar Indian villages on the Merced. In the Tuolumne country, also, a primitive transmountain route gave access via Sonora Pass to the favored locality now known as Bridgeport Valley. The wagon road which was opened here very early in the gold-rush period followed closely the route of the Indians. That there were prehistoric lanes of travel in the high mountains which connected the Sonora Pass and Mono (Bloody Canyon) routes seems likely but no record of such north-south trails of the Indians has been handed down, other than the statements made by Walker and Leonard regarding their route from the Walker River country to the Tuolumne-Merced divide.

The country south of the Merced drainage system was popular, both with the Miwok and the Chukchansi, a group of the Yokuts Indians. Kroeber (1925, pp. 446, 481-482, 526) has recorded the distribution of ancient Miwok villages on the South Fork of the Merced, on Mariposa Creek, and on the Chowchilla and Fresno rivers. The primitive trails which connected these villages provided a network of lanes through the hills well known to J. D. Savage and his contemporary forty-niners who frequented the hills and stream courses north of the San Joaquin River. These Indian trails became the first routes followed by the miner and his pack outfits. A few were “improved” by their first white users to become fairly good horse trails and later some of them were transformed into wagon roads. Today the old routes are not easily distinguished from the more recent logging roads which lace back and forth everywhere through the pine country south of the park, but the investigative motorist who will check against the maps made prior to the period of logging at the turn of the century may identify the old routes and follow them in exploring the country surrounding Wawona, Mariposa, Miami, Nipinnawasee, Hites Cove, Fish Camp, Bear Valley, Hornitos, and several other historic and prehistoric sites in the Mariposa region.

The Chukchansi, northernmost of the Yokuts, occupied the country south of the Fresno River and at times crossed that stream and overlapped upon the lands of the Miwok. Prior to the Yosemite Indian War with the whites, 1850-1852, they seem to have been on friendly terms with the Miwok. Chukchansi villages close to the border of Miwok territory existed at Fresno Flats (near the present Oakhurst, Madera County), Coarse Gold, Magnet, and on the San Joaquin near Hutchins. As was true of the Miwok villages, primitive trails connected these rancherias and extended into the country of the Chukaimina on the south and into the Mono territory to the east. In this part of the Sierra, the Monos claimed a goodly part of the west slope, including the present Bass Lake region and the higher country drained by the San Joaquin and Kings rivers. At the time of the Yosemite Indian War, these west-slope Piutes (Monos) were allied with the Chowchillas and Chukchansi. The intricate trail system of the densely populated belts, characterized by the Digger pine (Upper Sonoran Zone) and the oaks and ponderosa pine (Transition Zone), fed westward into major routes to the great San Joaquin Valley and eastward to high passes on the crest of the Sierra. Of these last-mentioned routes, those across Sonora Pass, Bond Pass, Buckeye Pass, Bloody Canyon, Agnew Pass, Mammoth Pass, Mono Pass (headwaters of the South Fork of the San Joaquin River), Pine Creek Pass, and Piute Pass were especially important to the Indians of the Yosemite region. At least some of these passes were traversed by horses before the advent of the white man.

By George Fiske On the First Trail to the Top of Vernal Fall |

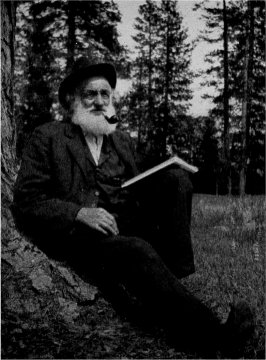

By Mode Wineman John Conway, a Pioneer Trail Builder |

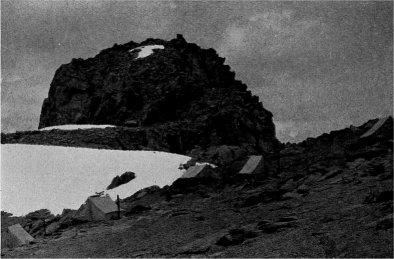

Mount Conness and the Observatory Camp |

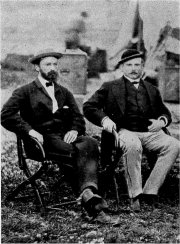

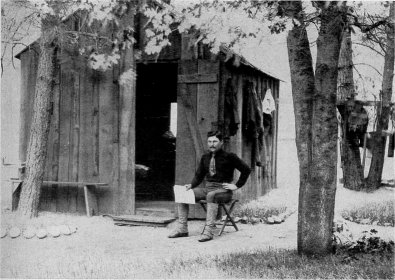

James T. Gardiner and Clarence King,

|

Professor Davidson (right) and

|

More than a few of the Indians of the Yosemite region had, prior to the gold rush, lived in the Spanish mission towns along the coast. Adam Johnston, Indian agent at the time of the Yosemite Indian War, stated of the Chowchilla and Chukchansi, “The most of them are wild, though they have among them many who have been educated at the missions, and who have fled from their real or supposed oppressors to the mountains. These speak the Spanish language as well as their native tongue.” (Russell, 1931, p. 172.) As might be expected, the mountain tribes maintained their long-established contact with the Indian population of the lower valleys, and numerous routes led from the ra[n]cherias of the hill tribes out upon the San Joaquin Valley and to the coast.

As we have seen, the first penetration of the Yosemite Valley by white men was the result of miners’ activities in the Mariposa hills. In reaching the hills and in entering the valley, the white prospectors of the gold-rush period followed well-defined trails long used by Indians. Within a few years after the close of hostilities with the Sierra tribes, the events described in the chapter on early mining excitements east of Yosemite took place. Here, also, the primitive paths of the Indian opened the way. The sheepherder, contemporary with the miner of the high country, also followed the trails of the Indian, and his flocks, together with the cattleman’s herds, did their part in “grading” the routes and making them conspicuous.

When Yosemite National Park was created in 1890, the U. S. Army took over the administration of the federal area which almost surrounded the state reservation. To aid patrolling in the park, a full program of exploration and mapping was launched. Capt. Alexander Rodgers, Col. Harry C. Benson, Major W. W. Forsyth, and Lts. N. F. McClure and Milton F. Davis made particularly important contribution to the work.

The existing fine system of trails so important to protection and enjoyment of Yosemite National Park had its inception in the plan of the U. S. Army. Almost at once after assuming responsibility for the care of the park, commanding officers initiated construction of trails, and at this juncture the location of primitive Indian trails was no longer a prime consideration in defining routes. The story of trail building by the U. S. Army will be told in a later part of this chapter.

It was inevitable that in the exploration for trails and passes, certain peaks should be climbed. The first recorded ascents of Yosemite’s peaks are attributed to members of the various survey parties. Perhaps the first was the ascent of Mount Hoffmann in 1863 by Whitney, Brewer, and Hoffmann. King climbed it in 1864 and with Gardiner climbed Mount Conness that same year, following with an ascent of Mount Clark, not without adventure, in 1866. Muir climbed Mounts Dana and Hoffmann, and far more difficult Cathedral Peak, three years later. Probably the first Yosemite ascent for the challenge of it by a casual tourist was that of Mount Lyell, highest peak in the park, in 1871. According to Hutchings:

Members of the State Geological Survey Corps having considered it impossible to reach the summit of this lofty peak, the writer was astonished to learn from Mr. A. T. Tileston [John Boies Tileston] of Boston, after his return to the Valley from a jaunt of health and pleasure in the High Sierra, that he had personally proven it to be possible by making the ascent. Incredible as it seemed at the time, three of us found Mr. Tileston’s card upon it some ten days afterward.

Mr. Tileston, writing to his wife from Clark and Moore’s after the climb on Mount Lyell, explained that he ascended nearly to the snow line on August 28, 1871, and next morning “climbed the mountain and reached the top of the highest pinnacle (‘inaccessible, according to the State Geological Survey’) before eight.” (Tileston, 1922, pp. 89-90.)

John Muir reached the summit of Mount Lyell later that year. Muir undoubtedly climbed in part as a response to the challenge of summits but could hardly be considered a casual tourist.

Four years later another summit, of which Whitney had said, it “never has been, and never will be trodden by human foot,” was ascended by a man climbing merely for the fun of it. In 1875, George G. Anderson, continuing where John Conway, a valley resident, had been stopped by difficulty and danger, tackled the climb of Half Dome with ideas of his own. According to Muir:

Anderson began with Conway’s old rope, which had been left in place, and resolutely drilled his way to the top, inserting eye-bolts five or six feet apart, and making his rope fast to each in succession, resting his feet on the last bolt while he drilled a hole for the next above. Occasionally some irregularity in the curve, or slight foothold, would enable him to climb a few feet without the rope, which he would pass and begin drilling again, and thus the whole work was accomplished in less than a week.

Anderson’s climb was the beginning of a search for routes to prominent heights in Yosemite that continues today. The fame of Yosemite’s wonders was spreading through the world, and the advent of stage roads brought a multitude of visitors who preferred to see the region without having to drill to do so. It was imperative that officials in charge of the state reservation improve and multiply the faint Indian trails in order that eager visitors might reach the valley rim and the High Sierra beyond.

Because appropriations made by the state legislature for the use of the Yosemite Valley Commission were too small to enable that executive body to undertake a program of trail building, toll privileges were granted to certain responsible individuals in return for the construction of some of the much-needed trails. Albert Snow, John Conway, James McCauley, Washburn and McCready, and James Hutchings were prominent in this contractual arrangement with the Yosemite commissioners.

Two trails antedate the regime of the Yosemite Valley Com[mis]sioners—the trail to Mirror Lake and the Vernal Fall Trail. No record exists identifying the builders of these pioneer trails. Albert Snow, 1870, built a horse trail from “Register Rock” on the Vernal Fall Trail, via Clark Point, to his “La Casa Nevada” on the flat between Vernal and Nevada falls. In 1871, John Conway, working for McCauley, started construction of the Four Mile Trail from the base of Sentinel Rock to Glacier Point. The project was completed in 1872. The old Mono Trail of the Indians between Little Yosemite and Glacier Point was followed by Washburn and McCready when they constructed their toll route here in 1872. In 1874, James Hutchings met the cost of a horse trail up Indian Canyon, which by 1877 already had fallen into such disrepair as to make it accessible only to hikers. The disintegration progressed rapidly, and the “improved” aboriginal route to the north rim found use during a comparatively few years of Yosemite tourist travel. Geographically and topographically it has much to commend it; in the current master plan of Yosemite National Park it is carried as the trail proposal calculated “to provide the best all-year access to the upper country on the north side of the valley.” Early action is expected which will place it on the map again. The Yosemite Falls Trail, started by John Conway in 1873 and completed to the north rim in 1877, was carried by its builder and owner still higher to the summit of Eagle Peak, highest of the Three Brothers. John Conway’s homemade surveying instruments used in trail building are preserved in the Yosemite Museum.

By 1882 the State Legislature initiated a program of purchasing and maintaining the Yosemite trails which had been privately built and operated on a toll basis. The Four Mile Trail

By Ralph Anderson, NPS Present-day Trail Work—Oiling the Eleven-Mile Trail |

Gabriel Sovulewski in 1897 |

By Ralph Anderson, NPS Mount Maclure and Its Glacier |

By Ralph Anderson, NPS Measuring the Mount Lyell Glacier |

At the time Yosemite National Park was established a great part of the northern section of the reservation was quite unknown except to cattlemen, sheepmen, and a few prospectors and trappers. As previously mentioned, the U. S. Army officers responsible for the administration of the national park at this time opened a new era in High Sierra trail development. From 1891 to 1914 a succession of officers, with a number of troops of cavalry, worked with diligence and with great ingenuity in locating trails, in contracting for their construction, and in counteracting the forces of exploiters who looked upon this great mountain domain as their own. At that time the back country trails were limited to the Tioga Road, which had deteriorated to the status of a horse trail; a trail along the southern boundary from Wawona to Crescent and Johnson lakes and Chiquito Pass, thence to Devils Postpile; the old Indian route from Wawona to Tuolumne Meadows via Cathedral Pass; two trails to Hetch Hetchy and Lake Eleanor from Hog Ranch, near the present Mather Ranger Station; and a trail from Tuolumne Meadows to Mount Conness. This dearth of marked routes was corrected quickly. Regular patrol routes for protective purposes were established, and the soldiers located, marked, and supervised the construction of the trails needed in policing the area. The large “T” blazed on the trees along the routes of the cavalrymen remain as evidences of the Army’s activities and are still familiar signs in much of the Yosemite back country.

By the time of the return of the Yosemite Grant and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to Federal administration in 1906, the Army had worked wonders in providing a system of trails. C. Frank Brockman (1943, p. 96) summarizes the story as follows:

The original trail system of 1891 had been extended to include a trail up Little Yosemite Valley to Merced Lake, Vogelsang Pass and thence down Rafferty Creek to Tuolumne Meadows, a route that is familiar to all High Sierra hikers of the present day. The Isberg Pass trail to the east boundary of the park had been marked and Fernandez Pass, farther to the south, had also been rendered accessible by a trail that branched from the original trail along the southern boundary. The present trail from Tuolumne Meadows up the Lyell Fork of the Tuolumne to Donohue Pass also dates from this period. From Tuolumne Meadows a trail also reached out into the remote northern portion of the park to the vicinity of Glen Aulin, thence up Alkali Creek to Cold, Virginia, and Matterhorn canyons. From the latter point this route continued westward to Smedberg Lake, down Rogers Canyon, eventually passing through Pleasant Valley and over Rancheria Mountain to Hetch Hetchy Valley. The Ten Lakes area was accessible by means of a trail originating on the Tioga Road near White Wolf, and from Hetch Hetchy Valley trails radiated to Tiltill Mountain, Miguel Meadow, Lake Eleanor, Vernon Lake, and up Moraine Ridge to a point near what is today known as the “Golden Stairs,” overlooking the lower portion of Jack Main Canyon. A route approximating the present Forsythe trail from Little Yosemite around the southern shoulder of Clouds Rest to Tenaya Lake had been established, and from Tenaya Lake the point now known as Glen Aulin could be reached by the McGee Lake trail. The routes taken by these early trails were essentially the same as those of the present day and points mentioned will be familiar to all who enjoy roaming about the Yosemite back country.

When the National Park Service came into existence in 1916, the broad design of the trail system was essentially as it is at present. The more important trails constructed during the last years of Army administration and in the first years of the National Park Service regime include the Tenaya zigzags built in 1911; the Glen Aulin-Pate Valley route, 1917-1925; the Babcock Lake Trail; the Yosemite Creek-Ten Lakes Trail; the Ledge Trail to Glacier Point, 1918; the Harden Lake-Pate Valley Trail, 1919; Pate Valley-Pleasant Valley Trail, 1920; and the Ottoway Lakes-Washburn Lake Trail in 1941.

Gabriel Sovulewski, who for more than thirty years supervised the construction of Yosemite trails, once outlined for me the amazing story of the evolution of the trail system from Indian routes and sheep trails (Sovulewski, 1928, pp. 25-28). Mr. Sovulewski stated, “Most of these improvements were made on my suggestion, and sometimes at my insistence, yet it is necessary to bear in mind that the credit is not all due to me, even though I did work hard. I share the credit with all superintendents under whom I have served. They gave me freedom to do the work which I have enjoyed immensely.”

Col. H. C. Benson, one of the superintendents referred to by Mr. Sovulewski, wrote in 1924:

The successful working out of the trails and the continuation of developing them is due largely to the loyalty and hard work of Mr. Gabriel Sovulewski. Too much credit can not be given to this man for the development of Yosemite National Park. (Brockman, 1943, p. 102.)

A fitting climax to the High Sierra trails in Yosemite National Park is found in that portion of the trail system which has been designated the John Muir Trail. Beginning at the LeConte Lodge in Yosemite Valley, this route follows the Merced River Trail to Little Yosemite, thence along the ancient Indian route over Cathedral Pass to Tuolumne Meadows, up the Lyell Fork of the Tuolumne to Donohue Pass (where the trail leaves the national park), along the east slope to Island Pass, then back to the headwaters of westward-flowing streams to Devils Postpile and Reds Meadow on the San Joaquin, south to Mono Creek and other tributaries of the South Fork of the San Joaquin, into Kings Canyon National Park at Evolution Valley, over Muir Pass to the headwaters of the Middle Fork of the Kings, over Mather Pass in the South Fork of the Kings, over Pinchot Pass, Glen Pass, and into Sequoia National Park at Foresters Pass, thence south to Mount Whitney. At Whitney Pass the route descends the east slope until it connects with a spur of the El Camino Sierra at Whitney Portal above the town of Lone Pine. Along the route are 148 peaks more than 13,000 feet in height. The Sierra crest, itself, is more than 13,000 feet above the sea for eight and one-half miles adjacent to Mount Whitney. The trail traverses one of the most extensive areas yet remaining practically free from automobile roads.

In Sequoia National Park, the High Sierra Trail from Giant Forest to Mount Whitney enters the John Muir Trail on Wallace Creek, a tributary of the Kern. Thus does the John Muir Trail connect the national parks of the Sierra, traversing in some 260 miles most of the grandest regions of the High Sierra.

The National Park Service, the Forest Service, and the State of California have co÷perated in making the John Muir Trail a reality. The phenomenal route had its inception during the 1914 Sierra Club Outing, when it was suggested to officers of the club that the State of California might well appropriate funds with which to develop trails in the High Sierra. Upon the death of John Muir, president of the club, appropriation bills were introduced for the purpose of creating a memorial trail. The first appropriation of $10,000 enabled the state engineer, Wilbur F. McClure, to explore a practical route along the crest of the Sierra from Yosemite to Mount Whitney. McClure made two trips into the Sierra and then conferred with the Sierra Club and officers of the U. S. Forest Service before designating the route. During the next twenty years several state appropriations were forthcoming, and the federal agencies most concerned, the Forest Service and the National Park Service, entered into the program of locating and building the trail. The earlier explorations of Muir, Solomons, LeConte, and numerous state and federal survey parties contributed to the success of the undertaking. The maps of the Geological Survey greatly facilitated the work.

While Stephen T. Mather was still Assistant Secretary of the Interior and before the National Park Service was created, the “Mather Mountain Party of 1916” assembled in Yosemite Valley preparatory to an inspection of the John Muir Trail. This expedition received the support of the Geological Survey. Frank B. Ewing, at that time an employee of the Geological Survey, was chief guide and general manager. As an employee of the National Park Service, he has remained in Yosemite National Park ever since that early march along the John Muir Trail and has been a principal party to the National Park Service trail developments previously described. The section of the John Muir Trail in Yosemite National Park was born and has matured under Ewing’s personal supervision. Mr. Mather’s expedition of 1916 helped to crystallize ideas regarding the Muir Trail and established it in the official minds and master plans of the new National Park Service and the U. S. Forest Service. Robert Sterling Yard, a member of the Mather party and later editor for the new bureau, wrote a sparkling account of the expedition (Yard, 1918). The route at that time was the same within Yosemite National Park as it is today, but the physical condition of the trail has improved mightily. The Mather party traveled the John Muir Trail to Evolution Valley, beyond which the trail was described as impassable to horses. From there the party moved westward to the North Fork of the Kings, then south to the Tehipite Valley, Kanawyers on the South Fork, and yet further southward to the Giant Forest. Today the Giant Forest is more accessible from the John Muir Trail via the High Sierra Trail.

In promoting the development of the John Muir Trail and in fostering the use of High Sierra trails, generally, the Sierra Club has ever been preŰminent among the advocates of mountaineering. Among its members are many individuals who have contributed to the shaping of National Park Service policies. This club, which was organized about the same time that Yosemite National Park was created, defined its purposes: “To explore, enjoy, and render accessible the mountain regions of the Pacific Coast; to publish authentic information concerning them; to enlist the support and cooperation of the people and the Government in preserving the forests and other natural features of the Sierra Nevada.” For nearly half a century the Sierra Club has centered its attention upon the security and well-being of the natural attributes of Yosemite and has worked to make those attributes known and appreciated. The national parks, national forests, and state parks, generally, have benefited greatly by the continuous interest of the club, and the trail and road systems of Yosemite National Park, especially, have received its study.

With the completion of an all-year highway into Yosemite Valley and the realignment of portions of the Big Oak Flat and Tioga roads, the accessibility of Yosemite National Park to the motorist reached its peak, and since that time serious thought has been given to modification of the road system. The Commonwealth Club, in a comprehensive report entitled, “Should We Stop Building New Roads into California’s High Mountains?” concluded that accessibility had already reached, if it had not passed, a desirable maximum, on the basis of a stand for the preservation of mountain wilderness values made by many sportsmen’s organizations and the Sierra Club. The National Park Service gave consideration, in its Yosemite Master Plan, to the abandonment and obliteration of certain roads which were either superseded by highways or which could be relocated to reduce any detrimental effects upon the mountain landscape. Col. C. G. Thomson led in establishing this trend.

Studies were made by the park administration, the concessionaire, and various organizations outside of the park of means by which present-day visitors, who were now arriving by automobile in hurried throngs numbering as many as 30,000 persons on a single holiday week end, might enjoy the park to some degree at least in the manner that the pioneers had enjoyed it. Improvement of the trails, of outlying facilities, education in the means of trail travel, and the development of an all-season program that would help to spread the peak of travel into a plateau, were steps taken and which are being taken in the attempt to halt the tendency of the public to make of Yosemite Valley an urban “resort.”

High Sierra camps were developed, as described elsewhere in this book. They were visited by travelers afoot or in the saddle, and “foot-burners” and pack outfits visited the remote regions of the park, where no improvements upon nature are permitted other than those which a man can carry in—and carry back out again when he leaves. The numbers of people who are attracted to the back country have increased mightily, but the congestion of crowds in Yosemite Valley is still great. This fact in itself constitutes a reason for increasing the effort to introduce visitors to the wonders of the wild high country.

David R. Brower, an officer of the Sierra Club and an ardent proponent of rock-climbing as a sport, and an accomplished skier, has reviewed the development of these forms of recreation in Yosemite. He has kindly agreed to my use of the following portion of an enlightening account, most of which has not previously appeared in print:

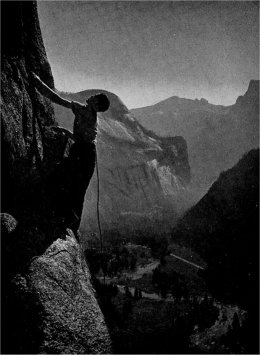

“To a few people—fortunately, perhaps, a very few—even a trail detracts a little from the feeling of ‘roughing it.’ Too clearly, the foot of man, or of mule, has trod there before them. Consequently, those who would get especially close to nature have become skilled in woodcraft so as to take care of themselves and have then struck off not only from the highways and roads, but also from the horse trails and footpaths. Muir and Anderson were pioneers in this form of recreation. A few have carried on where they left off. Routes were found through trailless Tenaya Canyon to the high country above; Muir Gorge, in the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne, presented an obstacle where the waters of that river were confined in a narrow, vertical-walled box canyon, but it has proved not to be an obstacle to good swimmers in periods of low water. Muir discovered Fern Ledge and crossed it along the tremendous face of the Yosemite Falls cliff, until he was under the upper fall itself. Charles Michael, years later, and William Kat, to this day, followed Muir’s footsteps and made new ones of their own on other Yosemite byways, such as the Gunsight to the top of Bridalveil Fall, Mount Starr King, the Lower Brother. For the most part these men, and others of similar bent, climbed alone. Michael was almost to regret it when, on an ascent of Piute Point, he fell a few feet, broke his leg, and was just able to drag himself back to the valley—to climb again when the break had knitted.

“These pioneers of the byways were limited, not by lack of enterprise, but by lack of modern equipment and the technique for its use; both of these required assets came to Yosemite in 1933. A year before that a Rock-Climbing Section was formed in the Sierra Club, and its members brought Alpine technique, which they had practiced and improved in local metropolitan rock parks, to Yosemite. Skillfully using rope and piton technique, and developing their balance climbing to a point where they are able to ascend Half Dome without recourse to any artificial aids, much less cableways, members of this and similar sections, men and women alike, have pioneered many new routes on the valley walls, some extremely difficult. The present total of routes to the rim, exclusive of the trails, is forty-five. Spires and pinnacles not accessible by other means were especially challenging. The higher and lower

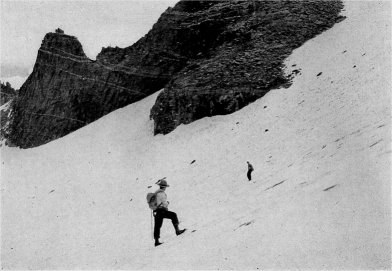

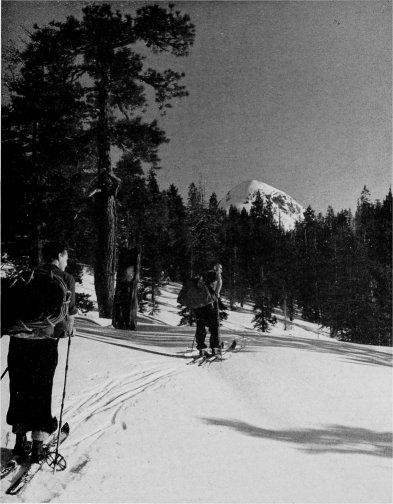

By D. R. Brower Ski Mountaineering Party near Mount Starr King |

By D. R. Brower Climbing on the Three Brothers |

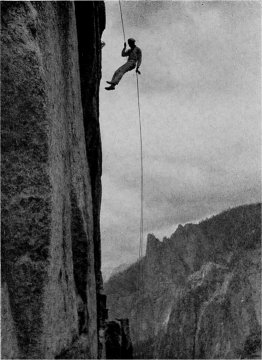

By R. M. Leonard Descending Lower Cathedral Spire |

“Construed at present as the ultimate in technical rock-climbing was the ascent, September 2, 1946, of the Lost Arrow by the party of Jack Arnold, Robin Hansen, Fritz Lippmann, and Anton Nelson. The party used more than a thousand feet of rope and many pounds of mountaineer’s hardware. They first managed to throw a light line over the summit. Two men remained in support at the rim. The other two went down a rope to the notch separating the pinnacle from the valley wall, and with expert technique were able to climb 100 feet of the rock’s outer face, nearly 3,000 sheer feet above the valley floor, until they could reach the lower end of the line. With this they pulled rope over the summit. Another 100 feet of climbing on that rope, with help from the men on the rim, brought them to the top on the evening of the third day. On the crowded, rounded summit they drilled small holes for two expansion bolts, anchored ropes to them, and in the moonlight worked across the gap to the rim on the airy, swinging ropes.

“Needless to say, such climbs as this should not be undertaken without the necessary background of experience. Foolhardy attempts by the overoptimistic to take short cuts or cross-country routes into unknown hazards all too often result in arduous and dangerous rescue operations by park rangers. The National Park Service requires, in Yosemite and in other ‘mountaineering’ parks, that persons desiring to climb off the trail register first at park headquarters, where, as a matter of the visitor’s own protection, he can be advised whether he has the adequate equipment or skill for his proposed undertaking, and where he announces his destination so that rangers will know where to look for him in case of trouble.

“If trails or cross-country routes have afforded the summer visitor a fuller knowledge of Yosemite National Park and its hidden wild places, certainly the improvement of access to various park areas in winter has also increased the enjoyment of the superlative scenery for which Yosemite was set aside as a national park in the first place.

“In the first days of winter sports in Yosemite, snowballing, tobogganing, skating, and sliding down small hills on toe-strapped skis was enough for the winter visitor. Snow, to Californians at least, was novelty enough in itself. But the surge of interest in skiing as a sport of skill that arrived after World War I, the resulting vast improvement in ski equipment and apparel, and the winter accessibility brought about by use of snow-removal equipment, inevitably stimulated skiers to demand greatly improved facilities for skiing. The National Park Service, required by law to be custodians of outstanding scenic resources for all the people, in all seasons, for present and future enjoyment, very properly ‘made haste slowly.’ Other areas, administered by agencies whose obligations were less exacting, developed facilities far more rapidly, and the pressure on the National Park Service, in Yosemite and elsewhere, was greatly increased.

“Ski development in Yosemite involved serious scenic, economic, and geographic considerations. The development should not damage the scenic values for which the park was created. It should, nevertheless, be so situated that the skier could enjoy that scenery without going far beyond the areas in which utilities were available; otherwise, the facilities would be used primarily by persons who wanted only to ski and not to enjoy the Yosemite scene. Such persons could be better accommodated elsewhere. The area developed for skiing should not be so close to the valley rim as to be dangerous. From the concessionaire’s standpoint, the development should make use of, and not duplicate, hotel facilities already available; otherwise, it would not be worth the financial risk. Where the Park Service was concerned, economically, it should be close enough to the valley not to require excessive road maintenance and snow removal and should not be too difficult to administer, for the Park Service, after all, could only spend what Congress appropriated in the annual budget. As for the man who skied in Yosemite for the sake of skiing, his wants were simple. In the aggregate, he wanted high and low cost accommodations built at an elevation where the best snow lay the longest and the slopes were most open; he wanted satisfactory uphill transportation to enable him to spend most of his time and energy sliding down; he wanted cleared runs and marked trails, outlying huts for touring, and excellent ski instruction patterned after the best European ski schools. He wanted ski competition scheduled, and long courses on which to race. He, moreover, wanted all this in a quantity that would take care of four thousand or more skiers on a week end, without overcrowding the facilities or overburdening his purse.

“What could the National Park Service do? The development at Badger Pass was the result. The ski house, upski, rope tows, Constam lift, the runs of various types, the ski school, the cleared roads and parking area, the ranger ski patrol, the marked touring trails, and the touring hut at Ostrander Lake are all part of a development that is compatible with the national park concept. Improvements will inevitably follow. In the development so far, full enjoyment has been provided for the tens of thousands of skiers who, although they like improvements, would still prefer that the administrators of the national parks continue to make haste slowly in any attempt to improve upon the natural scene.”

Next: Hotels • Contents • Previous: Stagecoach Days

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/one_hundred_years_in_yosemite/explorers.html