| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > 100 Years in Yosemite > Tourists in the Saddle >

Next: Stagecoach Days • Contents • Previous: Pioneers

|

|

|

| Woodcut from the first edition (1931) |

Hutchings and his first sight-seers “spent five glorious days in luxurious scenic banqueting” in the newly discovered valley and then followed their Indian guides over the return trail to Mariposa. Upon their arrival in that mountain city, they were besieged with eager questioners, among whom was L. A. Holmes, the editor of the Mariposa Gazette, which had recently been established. Mr. Holmes begged that his paper be given opportunity to publish the first account from the pen of Mr. Hutchings. His request was complied with, and in the Gazette of July 12, 1855, appears the first printed description of Yosemite Valley, prepared by one uninfluenced by Indian troubles or gold fever.

Journalists the country over copied the description, and so started the Hutchings Yosemite publicity, which was to continue through a period of forty-seven years. Parties from Mariposa and other mining camps, and from San Francisco, interested by Hutchings’ oral and printed accounts, organized, secured the same Indian guides, and inaugurated tourist travel to the Yosemite wonder spot.

Milton and Houston Mann, who had accompanied one of these sight-seeing expeditions, were so imbued with the possibilities of serving the hordes of visitors soon to come that they set to work immediately to construct a horse toll trail from the South Fork of the Merced to the Yosemite Valley. Galen Clark, who also had been a member of one of the 1855 parties, was prompted to establish a camp on the South Fork where travelers could be accommodated. This camp was situated on the Mann Brothers’ Trail and later became known as Clark’s Station. It is known as Wawona now. The Mann brothers finished their trail in 1856.

Old Indian trails were followed by much of the Mariposa-Yosemite Valley route. The toll was collected at White and Hatch’s, approximately twelve miles from Mariposa. At Clark’s Station (Wawona), the trail detached itself from the Indian route and ascended Alder Creek to its headwaters. Here it crossed to the Bridalveil Creek drainage and passed through several fine meadows, gradually ascending to the highest point on the route above Old Inspiration Point on the south rim of Yosemite Valley. From this point it dropped sharply to the floor of the valley near the foot of Bridalveil Fall. The present-day Alder Creek and Pohono trails traverse much of the old route.

Several years after the pioneer trail was built, sheep camps were established on two of the lush meadows through which it passed. They were known as Westfall’s and Ostrander’s. The rough shelters existing here were frequently used by tired travelers who preferred to make an overnight stop on the trail rather than exhaust themselves in completing the saddle trip to the valley in one day. Usually, however, Westfall’s or Ostrander’s were convenient lunch stops for the saddle parties.

In 1869, Charles Peregoy built a hotel, “The Mountain View House,” at what had been known as Westfall Meadow and with the help of his wife operated a much-praised hospice every summer until 1875, when the coming of the stage road between Wawona and Yosemite Valley did away with the greater part of the travel on the trail.

The Mann Brothers’ Trail, which was some fifty miles in length, was purchased by Mariposa County and made available to public use without charge before construction of the stage road from Mariposa had been completed.

In 1856, the year that witnessed the completion of the Mariposa-Yosemite Valley Trail, L. H. Bunnell, George W. Coulter, and others united in the construction of the “Coulterville Free Trail.” Very little, if any, of this route followed existing Indian trails. The Coulterville Trail started at Bull Creek, to which point a wagon road already had been constructed, and passed through Deer Flat, Hazel Green, Crane Flat, and Tamarack Flat to the point now known as Gentry, and thence to the valley. Its total length was forty-eight miles, of which seventeen miles could be traveled in a carriage.

A second pioneer horse trail on the north side of the Merced began at the village of Big Oak Flat, six miles north of Coulterville, and followed a route north of the Coulterville Free Trail through Garrote to Harden’s Ranch on the South Fork of the Tuolumne River, thence to its junction with the Coulterville Trail between Crane Flat and Tamarack Flat.

Sections of all of these early routes passed over high terrain where deep snow persisted well into the spring. Early fall snow storms in these vicinities sometimes contributed to the hazards of travel. The trails found use during a relatively short season. The Merced Canyon offered opportunity to establish a route at lower elevation, but the difficulties of construction in the narrow gorge deterred all would-be builders until a short time prior to the wagon-road era. The Hite’s Cove route, which came into use in the early ’seventies, partly answered the need for a snow-free canyon trail. Hite’s Cove, where the John Hite Mine was located in 1861, is on the South Fork of the Merced some distance above its confluence with the Merced River. A wagon road eighteen miles in length made it accessible from Mariposa. Tourists using this route stopped overnight in Hite’s Cove and then traveled twenty miles in the saddle up the Merced Canyon to the valley.

Another means of reaching the valley on horseback via the Merced Canyon was developed soon after wagon roads had been built. Some Yosemite visitors, perhaps because of the poor condition of the roads at certain seasons, elected to leave the Coulterville stage route at Dudley’s, from where they went to Jenkins Hill on the rim of the steep walls of the Merced gorge. Here a horse trail enabled them to descend to the bottom of the canyon, thence up the Merced to the valley. This thirty-mile saddle trip involved an overnight stop at Hennesey’s, situated a short distance below the present El Portal.

Travel in the saddle, of course, was regarded by the California pioneer with few qualms. Likewise, the conveyance of freight on the backs of mules was looked upon as commonplace, and the success attained by those early packers is, in this day and age, wonderful to contemplate. In Hutchings’ California Magazine for December, 1859, appears a most interesting essay on the business of packing as then practiced among the mountaineers of the gold camps.

Pack animals and packers have not yet passed from the Yosemite scene, for much of the back country is, and always will be, we hope, accessible by trail only. Government trail gangs are dependent for weeks at a time upon the supplies brought to them upon the backs of mules. Likewise, those who avail themselves of High Sierra Camp facilities are served by pack trains. Present-day packing differs in no essential way from the mode of the ’fifties, except that it is often done by Indians instead of the old-time Mexican mulatero.

What one visitor of the pre-wagon days thought of the saddle trip into Yosemite Valley may be gathered from J. H. Beadle in his Undeveloped West. Beadle visited the Sierra in 1871 and approached the valley from the north.

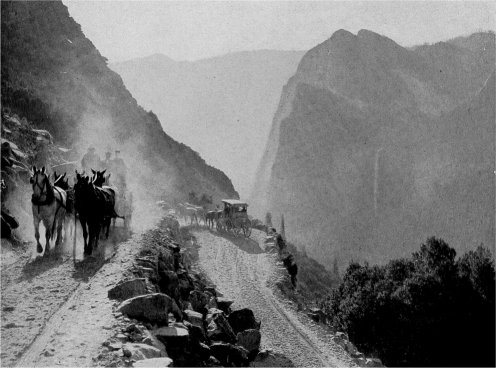

Thirty-seven miles from Garrote bring us to Tamarack Flat, the highest point on the road, the end of staging, and no wonder. The remaining five miles down into the valley must be made on horseback.

While transferring baggage—very little is allowed—to pack mules, the guide and driver amuse us with accounts of former tourists, particularly of Anna Dickinson, who rode astride into the valley, and thereby demonstrated her right to vote, drink “cocktails,” bear arms, and work the roads, without regard to age, sex, or previous condition of servitude. They tell us with great glee of Olive Logan, who, when told she must ride thus into the valley, tried practising on the back of the coach seats, and when laughed at for her pains, took her revenge by savagely abusing everything on the road. When Mrs. Cady Stanton was here a few weeks since, she found it impossible to fit herself to the saddle, averring she had not been in one for thirty years. Our accomplished guide, Mr. F. A. Brightman, saddled seven different mules for her (she admits the fact in her report), and still she would not risk it, and “while the guides laughed behind their horses, and even the mules winked knowingly and shook their long ears comically, still she stood a spectacle for men and donkeys.” In vain the skillful Brightman assured her he had piloted five thousand persons down that fearful incline, and not an accident. She would not be persuaded, and walked the entire distance, equal to twenty miles on level ground. And shall this much-enduring woman still be denied a voice in the government of the country? Perish the thought. With all these anecdotes I began to feel nervous myself, for I am but an indifferent rider, and when I observed the careful strapping and saw that my horse was enveloped in a perfect network of girths, cruppers and circingles, I inquired diffidently, “Is there no danger that this horse will turn a somerset with me over some steep point?” “Oh, no, sir,” rejoined the cheerful Brightman, “he is bitterly opposed to it.”

We turn again to the left into a sort of stairway in the mountain side, and cautiously tread the stony defile downward; at places over loose boulders, at others around or over the points of shelving rock, where one false step would send horse and rider a mangled mass two thousand feet below, and more rarely over ground covered with bushes and grade moderate enough to afford a brief rest. It is impossible to repress fear. Every nerve is tense; the muscles involuntarily make ready for a spring, and even the bravest lean timorously toward the mountain side and away from the cliff, with foot loose in stirrup and eye alert, ready for a spring in case of peril. The thought is vain; should the horse go, the rider would infallibly go with him. And the poor brutes seem to fully realize their danger and ours, as with wary steps and tremulous ears, emitting almost human signs, with more than brute caution they deliberately place one foot before the other, calculating seemingly at each step the desperate chances and intensely conscious of our mutual peril. Mutual danger creates mutual sympathy—everything animal, everything that can feel pain, is naturally cowardly—and while we feel a strange animal kinship with our horses, they seem to express a half-human earnestness to assure us that their interest is our interest, and their self-preservative instinct in full accord with our intellectual dread. We learn with wonder that of all the five thousand who have made this perilous passage not one has been injured—if injured be the word, for the only injury here would be certain death. One false step and we are gone bounding over rocks, ricocheting from cliffs, till all semblance of humanity is lost upon the flat rock below. Such a route would be impossible to any but those mountain-trained mustangs, to whom a broken stone staircase seems as safe as an ordinary macadamized road.

At length we reach a point where the most hardy generally dismount and walk—two hundred feet descent in five hundred feet progress. Indeed half the route will average the descent of an ordinary staircase. Then comes a passage of only moderate descent and terror, then another and more terrible stairway—a descent of four hundred feet in a thousand. I will not walk before and lead my horse, as does our guide, but trail my long rope halter and keep him before, always careful to keep on the upper side of him, springing from rock to rock, and hugging the cliff with all the ardor of a young lover. For now I am scared. All pretense of pride is gone, and just the last thing I intend to risk is for that horse to stumble, and in falling strike me over that fearful cliff. At last comes a gentler slope, then a crystal spring, dense grove and grass-covered plat, and we are down into the valley. Gladly we take the stage, and are whirled along in the gathering twilight.

The vehicle that whirled Beadle over the flat of the valley floor was brought to Yosemite before roads were constructed and is now exhibited at the Yosemite Museum as “the first wagon in Yosemite Valley.”

The arrival of visitors prompted the building of shelters. The first habitation to be constructed by white men in Yosemite was a rough shack put up in 1855 by a party of surveyors, of which Bunnell was a member. A company had been organized to bring water from the foot of the valley into the dry diggings of the Mariposa estate. It was supposed that a claim in the valley would doubly secure the water privileges.

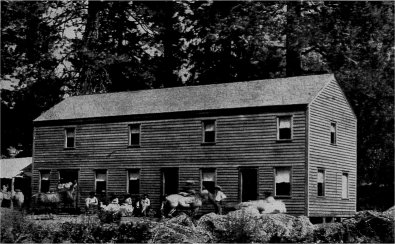

The first permanent structure was built in 1856 by Walworth and Hite. It was constructed of pine boards that were rived out by hand, and occupied the site of the 1851 camp of Boling’s party (near the foot of the present Four-Mile Trail to Glacier Point). It was known as the Lower Hotel until 1869, when it was pulled down, and Black’s Hotel was constructed on the spot.

In the spring of 1857, Beardsley and Hite put up a canvas-covered house in the old village. The next year this was replaced by a wooden structure, the planks for which had been whipsawed by hand. J. M. Hutchings was again in the valley in 1859, and his California Magazine for December of that year tells of the first photographs to be made in Yosemite. C. L. Weed, a pioneer photographer apparently working for R. H. Vance, packed a great instrument and its bulky equipment through the mountains to the Yosemite scenes. Photography was just then taking its place in American life. Mr. Weed’s first Yosemite subject was this Upper Hotel of Beardsley and Hite. [Editor’s note: Charles Leander Weed’s first photograph, taken June 18, 1859 was of Yosemite Falls, not Hite’s Hotel, which was photographed 3 days later—dea.] Hutchings and Weed decided on this occasion that they must visit the fall now called Illilouette, and Hutchings wrote:

The reader would have laughed could he have seen us ready for the start. Mr. Beardsley, who had volunteered to carry the camera, had it inverted and strapped at his back, when it looked more like an Italian “hurdy gurdy” than a photographic instrument, and he like the “grinder.” Another carried the stereoscopic instrument and the lunch; another, the plate-holders and gun, etcetera; and as the bushes had previously somewhat damaged our broadcloth unmentionables, we presented a very queer and picturesque appearance truly.

Hutchings published a woodcut made from the first photograph of the Yosemite hostelry in November of 1859; his book, In the Heart of the Sierras, again alludes to his presence in the valley when this first photograph was taken. [Editor’s note: Charles Leander Weed’s first photograph, taken June 18, 1859 was of Yosemite Falls, not the “Yosemite hostelry,” which was photographed 3 days later—dea.] Naturally, students of California history have been interested in learning more about the work of Weed, but in spite of serious attempts to procure more information on this photographer of 1859, nothing was brought to light. It was then something of a thrill to me to find myself in possession of an original print from the earliest Yosemite negative. That the print is genuine seems to be a fact, and the incidents relative to its discovery are worth the telling here.

Its donor, Arthur Rosenblatt, resided as a small boy within a few blocks of the Hutchings San Francisco home on Pine Street. Mr. Rosenblatt and his brothers played with the Hutchings children. In 1880 the Hutchings home was destroyed by fire. The small boys of the neighborhood searched the debris for objects worth saving, and Irving and Wallace Rosenblatt salvaged a pack of large water-stained photographs. Arthur Rosenblatt with forethought mounted these pictures in an old scrapbook. He has cherished them through the years that have passed. In June, 1929, he visited the Yosemite Museum and was interested in the historical exhibits. In his study of the displayed materials, he came upon a photographic copy of the old drawing of the “Hutchings House;” which has been taken from In the Heart of the Sierras. He recognized its subject as identical with one of the old photographs which he had preserved since 1880. He made his find known to the park naturalist, and immediately phoned to his San Francisco home and requested that the scrapbook be mailed at once to the Yosemite Museum. Upon its receipt, the old hotel photograph was segregated from the others, and comparisons were made with the drawing in the old Hutchings book and with the building itself. The print is obviously from the original Weed negative.

Hutchings’ visit of 1859 apparently convinced him of the desirability of residing in Yosemite Valley. During the next few years he spared no effort in making its wonders known to the world through his California Magazine. The spirited etchings of Yosemite wonders that were reproduced in the magazine from Weed’s photos and from Ayres’s drawings did much to convince travelers of the magnificence of Yosemite scenery. The stream of tourists who entered the valley grew apace in spite of the hardships to be endured on the long journey in the saddle. Horace Greeley was one of those who braved the discomforts in 1859 and gave his description of the place to hundreds of thousands in the East. Greel[e]y, foolishly, determined to make the 57-mile saddle trip via the Mariposa route in one day. He arrived at the Upper Hotel in Yosemite Valley at 1:00 A.M., more dead than alive, yet shortly afterward he wrote, “I know no single wonder of Nature on earth which can claim a superiority over the Yosemite.” His visit was made at a season when Yosemite Falls contained but little water, and he dubbed them a “humbug,” but his hearty praise of the general wonders played a significant part in turning the interest of Easterners upon the new mecca of scenic beauty.

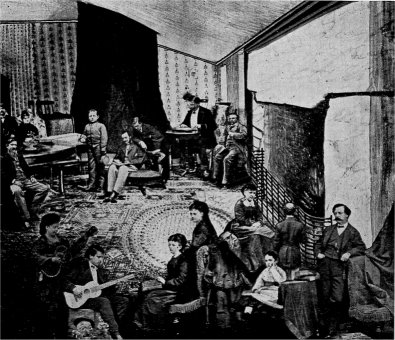

In 1864 J. M. Hutchings came to the Upper Hotel (Cedar Cottage) in the role of proprietor. The mirth and discomfiture engendered among Hutchings’ guests by the cheesecloth partitions between bedrooms prompted him to build a sawmill near the foot of Yosemite Falls in order to produce sufficient lumber to “hard finish” his hostelry. It was in this mill that John Muir found employment for a time. The hotel was embellished with lean-tos and porches, and an addition was constructed at the rear in which was completely enclosed the trunk of a large growing cedar tree. Hutchings built a great fireplace in this sitting room and proceeded to make the novel gathering place famous as the “Big Tree Room.”

A winter spent in the frigid shade of the south wall of Yosemite Valley convinced the Hutchings family that their “Big Tree Room” was not a pleasant winter habitation. They built anew and moved into the warm sunshine of the north side of the valley. With their own hands members of the family constructed a snug cabin among giant black oaks near the foot of Yosemite Falls and there spent the remainder of their Yosemite days.

Papers, letters, and photographs relating to the Yosemite experiences of the Hutchings family have been preserved by J. M. Hutchings’ daughter, Mrs. Gertrude Hutchings Mills, and by the family of his wife, the Walkingtons of England. Materials generously donated from these sources take important places in the collections of the Yosemite Museum and have greatly aided in the preparation of this volume.

J. M. Hutchings invested heavily in the construction of the Sentinel group of buildings and continued to be identified with the Yosemite as publicity agent, hotel proprietor, resident, official guardian, and unofficial champion until 1902. In that year, he met his death on the zigzags of the Big Oak Flat Road. In the 1902 register of the hotel, which was once the Hutchings House, is the following entry made by Mrs. Hutchings, the second wife of J. M. Hutchings:

November 8, 1902

Today leaving Yo Semite and all I love best.

Emily A. Hutchings

Thinking that some who come here may wish to know a little about the sad tragedy of Mr. J. Hutchings death, I would like to write a few words.

Because I had never seen Yo Semite in the autumn, my dear husband brought me here for a short holiday, on our way to San Francisco. We started from the Calaveras Big Trees and came via Parrots Ferry, and its beautiful gorge—the wonderful old mining center of Columbia, and its hitherto only surface-skimmed Gold Fields—Sonora and its good approaches, in its oiled and well graded roads—and thence to Chaffee and Chamberlains and to Crockers and their hearty hospitality. It has been a very pleasant experience, to see many friends on the way—most of them honored “Old Timers,” who have been the thews and sinews of the State, and who still hold their own in the rugged strength, which has brought them through to 1902.

From Crockers, we started on the last day of our journey [Oct. 31, 1902], continuing through the glorious Forests of the Sierras, the autumnal tints of which this year, have been of unusual grandeur— these beauties all being intensified in Yo Semite.

Coming down the Grade we were impressed beyond expression, and, when we reached the point where El Capitan first presents itself, my Husband said, “It is like Heaven.”

There was no apparent danger near but one of the horses took fright (probably a wild animal was at hand) and dashed away. When the Angel of Death reached Mr. Hutchings a few moments later—under the massive towering heights of that sun-illumined Cliff—“He” found him in the full vigour of life and high energetic purpose—but his grief-stricken wife prayed in vain that the ebbing tide would stay.

From the moment the sad accident was known, the greatest sympathy and kindness were shown, loving hands gave reverent aid— and on Sunday, Nov. 2, 1902, my dear husband was borne from the Big Tree Room and its time honored memories. The residents of the Valley and many of the Indians, who had long known him, followed. We laid him to rest, surrounded by nature in Her most glorious garb, and under the peaks and domes he had loved so well and had explored so fearlessly.

Emily A. Hutchings

Nov. 8, 1902

In 1941 and for several years thereafter, Yosemite Valley was visited by Cosie Hutchings Mills, daughter of J. M. Hutchings, born October 5, 1867, the second white child born in the valley. Elizabeth H. Godfrey, of the Yosemite Museum, obtained from Mrs. Mills both written and oral statements regarding the pioneer experiences of the Hutchings family in Yosemite. The interviews with Mrs. Mills were recorded by Mrs. Godfrey. Her manuscript, “Chronicles of Cosie Hutchings Mills,” and Mrs. Mills’ written reminiscences are preserved in the Yosemite Museum.

By C. L. Weed, 1859 First Yosemite Photograph—“Upper Hotel” |

The Big Tree Room |

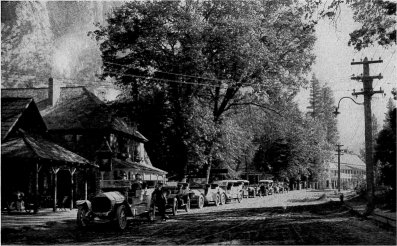

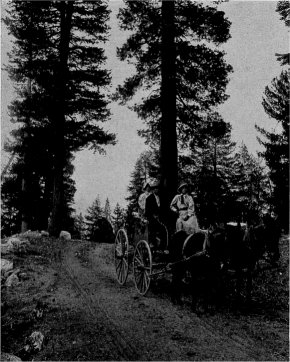

By J. T. Boysen The Big Oak Flat Route |

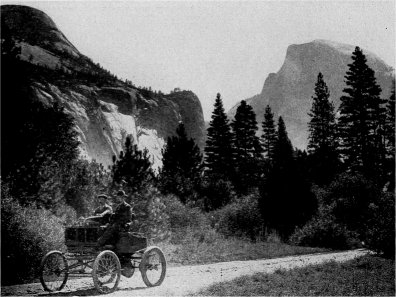

By J. T. Boysen The First Automobile—July, 1900 |

Early Yosemite Buses |

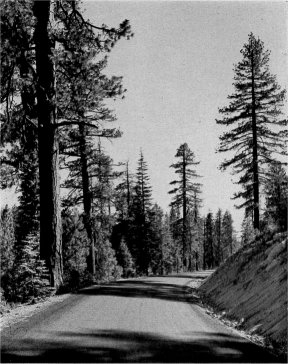

Old Tioga Road |

New Tioga Road |

Next: Stagecoach Days • Contents • Previous: Pioneers

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/one_hundred_years_in_yosemite/tourists.html