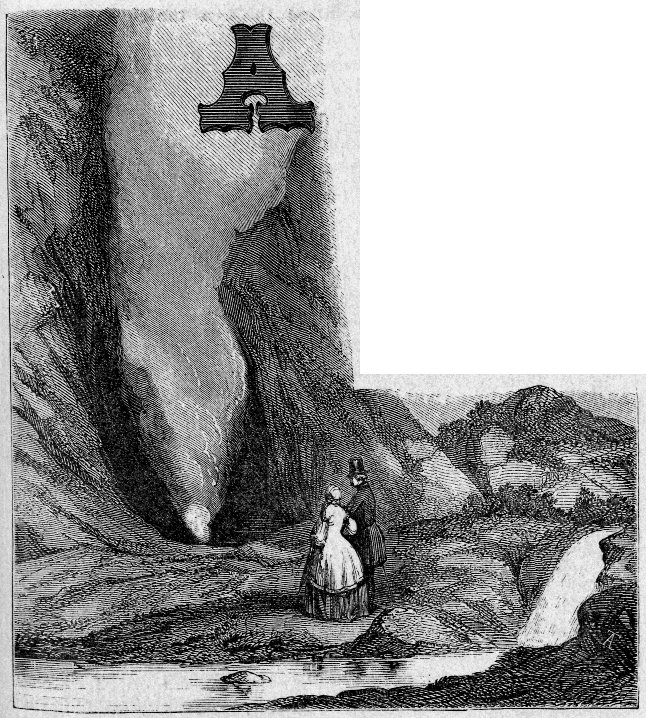

THE WITCHES’ CAULDRON

Sketched from nature by George Tirrell.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Scenes of Wonder & Curiosity > The California Geysers >

Next: Riffle-Box Waterfall • Contents • Previous: San Francisco

THE WITCHES’ CAULDRON Sketched from nature by George Tirrell. |

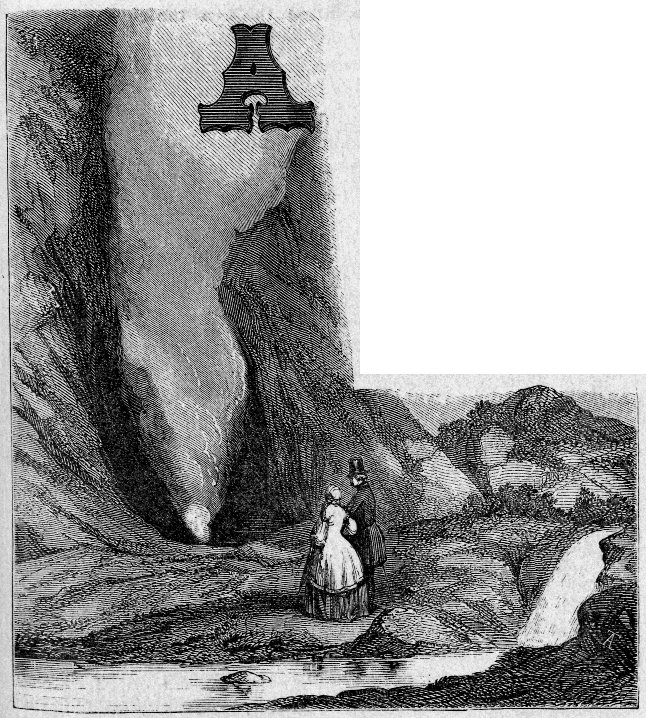

As the fine little steamer “Rambler” was sounding her last whistle, we received a parting injunction—writes an esteemed acquaintance* [* Mr. George Tirrell, designer and painter of the Panorama of California. ] — from friends on the Broadway street wharf, San Francisco, “to keep well aft,” and stepped on board.

It was one of the chilliest, dreariest, most disagreeable of San Francisco’s summer mornings. A dense fog, fresh from the great factory out on the Pacific, was rolling in over the hills at the back of the city, and hurrying across the bay before a stiff north-west wind. The waves, as they rolled along the sides of the shipping, or splashed among the piles, seemed to be playing a most melancholy march, to which the great army of fog-clouds moved across the cheerless water, and their commanding officer—the wind—seemed to be continually saying “forward,” as it whistled through the rigging of the ships.

The individual who is always just too late, made his appearance, as usual, as the steamer’s fasts were cast off, and her wheels commenced their lively though monotonous ditty in the water.

Two or three Whitehall boatmen, who were lying off the wharf, evidently expecting such a “fare,” gave their lazily playing skulls a vigorous pull, which sent their beautiful little craft darting into the wharf. The boy with the basket of oranges hastened to offer the would-be-traveller “three for two bits,” by way of consolation, and as he slowly proceeded up the dock again, the other boy with the papers and magazines called his attention to the last “Harper’s,” or “Hutchings’ California Magazine.”

The ten thousand voices of the city became blended into a continuous roar, as we glided out into the stream; the long drawn “go-o-o ahead,” or “hi-i-gh,” of the stevedores at their work, discharging the stately clippers, being about the only intelligible sounds to be distinguished above the mass.

Soon the outermost ship, on board of which a disconsolate looking “jolly tar” was riding down one of the head stays, giving it a “lick” of tar as he went, was passed, and we struck the strong current of wind which was blowing in at the Golden Gate (carelessly left open, as usual). The young giant of a city had become swallowed up in the gloom of the fog, and its thousands of busy people ceased to exist, except in our imaginations. After passing Angel Island, the fog began to lift; we were approaching the edge of the bank; and soon the sun appeared, hard at work at his apparently hopeless task of devouring the intruding fog, which had dared to interpose its cold billows between him and the bay, upon which be loves to shire.

The course of the boat was along the western side of Pablo Bay, close enough to the shore to give the passengers a fine view of it, as well as of the inland country, and the more distant mountains of the coast range. Large masses of misty clouds, which had become detached from the main fog bank, still partially obscured the sunlight, casting enormous shadows along the hill sides and across the plains, heightening, by contrast, the golden tinge of the wild oats, and giving additional beauty to the varied tints of the cultivated fields. Beyond, Tamal Pais, and other and lesser peaks of the Coast Range, piled their wealth of purple light and misty shadows, against the brightness of the western sky.

I wonder that our artists, in their search for the picturesque, have overlooked the splendid scene which Tamal Pais and the adjacent mountains present from the vicinity of Red Rock, or from the eastern shore of the straits. It is certainly one of the most picturesque scenes anywhere in the vicinity of San Francisco, especially toward sunset, when the long streaks of sunlight come streaming down the ravines, piercing with their golden light the hazy mystery which envelops the mountains, and brilliantly illuminating the intervening plains and hill-sides. From the familiarity of the view, a good picture would, without doubt, be much sought after.

The seamanship of the pilot was much exercised while navigating the “Rambler” up Petaluma Creek. The creek is merely a long, narrow, ditch-like indentation, which makes up into the flat tule plains at the northern side of Pablo Bay, and into which the tide ebbs and flows. Its course very much resembles the track of a man who has spent half an hour boating for a lost pocket-book in a field. If, after gazing awhile at the creek, the eye should be suddenly turned to a ram’s horn or a manzanita stick, the latter would appear perfectly straight, by comparison. First we go toward the north star awhile, then we come to a short bend where an immense amount of backing, and stopping, and going ahead occurs, which all results in running the boat hard and fast ashore. Then the pilot, perspiring freely from his violent exertions at the wheat, thrusts his head out of the window, and, after taking a survey of the state of affairs, sets himself to ringing the signal bells again. Then the crew get out a long pole, and planting one end in the bank, apply their united strength to the other. No movement! Then the captain heroically rushes ashore in the mud and tules, and calls for volunteers to help him push. Human

[“Rambler,” navigating Petaluma Creek.] |

Before reaching Petaluma, we met a little steamer coming down with a load of wood. She resembled me immense pile of wood with a smoke-stack in the centre, floating down the stream, and appeared to take up the whole width of the creek, when our passengers began to wonder how we were to get by. It was a tight fit. There was not room enough left between the two boats to insert this sheet of paper. The “Rambler” puffed, and from the depths of the wood pile was heard a sort of wheezing, as if half a dozen people with bad colds were down there somewhere, all trying to cough at once, and couldn’t. The captain gave utterance to a few more expletives, as the rough ends of the wood defaced the new paint on our boat; but the skipper of the wood-pile only laughed; yet, as the “Rambler,” in passing, scraped off two or three cords of his cargo, it then became our turn to laugh.

Petaluma was reached at last, and the passengers for Healdsburg found a stage in waiting. Jumping in, we were soon whizzing across the plains behind a couple of fine colts. The road lay directly up the Petaluma and Russian River Valleys. Past the ranches—along the sides of interminable fields of corn and grain—through the splendid park like groves—sometimes across the open plain, at others winding around the base of the hills, which make up from the eastern side of the valley.

Santa Rosa was reached by sunset. Our arrival was hailed by the ringing of a great number and variety of bells. How singular it is that the arrival of a stage-coach in a country town always sets the dinner-bells to ringing, especially if the occurrence happens about meal time.

By the time supper was despatched, and a pair of sober old stagers put to in the place of our frisky young colts, the moon had risen over the mountains, and was flooding the valley with her glorious sheen, tipping the fine old oaks with a silvery fringe of light, and laying their solemn shadows along the grass and across the road. A pleasant ride of two hours carried us to the end of our first day’s journey, Healdsburg.

On the following morning, we were recommended to apply at the stable opposite the hotel for horses. Having selected one warranted not to kick up nor stand on his hind legs, nor jump stiff-legged, nor play any other pranks, he was saddled and bridled at once. Our portfolio (which, for want of a better covering, was carried in an old barley sack) was slung on one side, and our wardrobe depended at the other. A whip was added to complete the outfit, accompanied by the observation that as “Old Pete” was apt to “soger,” “we might find it useful.”

Then the stable man attempted to describe the road to Ray’s Ranche. First, we should come to a bridge; a mile beyond that, see a house, to which we were to pay no attention, but look out for a haystack. Having found the haystack, we were to turn to the left, and would soon come to a long lane, that would lead us to another house, where we were either to turn to the right, or keep straight ahead, be had forgotten which. At this point of the description, a bystander interposed, saying that we must turn to the left; upon this, an argument sprung up between the two, which nearly led to a fight.

Finding that there was not much information to be elicited from those witnesses, “Old Pete” received a touch and started, with our head buzzing with right and left hand roads, while a regiment of ranches, lanes, and haystacks, seemed to be a “bobbing round” just ahead of the horse’s nose. We found the bridge, and saw the house, to which we were to pay no attention; there was no need of looking out for a haystack, for a dozen were in sight; so, selecting the biggest one, we turned to the left, according to the chart.

We rode along about a mile, and came to a fence which barred any further progress in that direction; then kept along the fence until we came to a lane which took us to a pair of bars. Let down the obstruction, traversed another lane, and at the end of it found ourselves in somebody’s dooryard. It was evident that we had taken the wrong road.

We now obtained fresh directions at the farm-house, but as three or four attempted at the same time to tell us the way—all talking at once, and each insisting upon his favorite route so that we speedily became mixed up again with another labyrinth of fences, lanes, and haystacks—we began to doubt the existence of such a place as “Ray’s Ranche.” It seemed forever retreating as we advanced, like the mythical crock of gold, buried at the foot of a rainbow, which we remembered starting in search of once, when a youngster.

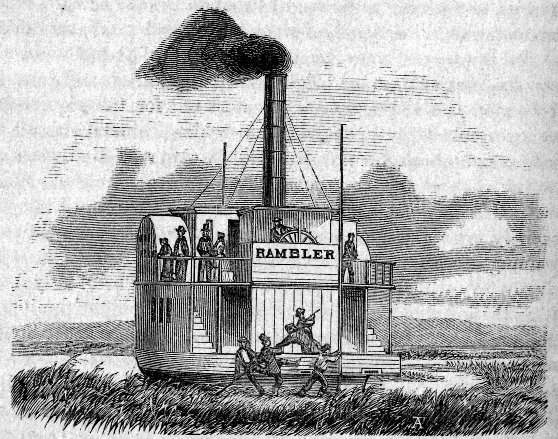

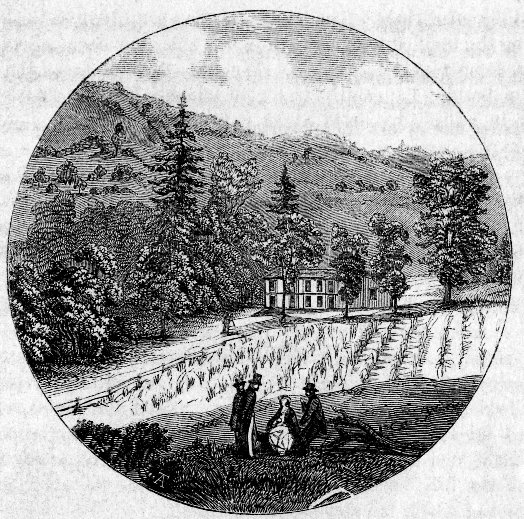

But the ranche was found at last, and a very fine one it is, too. The house is situated a little way up in the foot-hills, and commands a splendid view of Russian River Valley, the Coast Range, Mount St. Helens, etc. The ranche itself, garden, orchards, and fields of wheat and corn, is situated in a valley, just below the house, which makes up between the steep mountain sides. A

RAY’ RANCHE AND RUSSIAN RIVER VALLEY. |

We had the good luck here to fall in with Mr. G——, one of the proprietors of the Geysers, who was also on the way up. From the accounts which have been published, we expected to find the road from here a tough one. But it is nothing of the sort. It is a very good mountain trail, wide enough for a wagon to pass along its whole length. Buggies have been clear through, and could go again, were a few days’ work to be expended upon the trail. It is quite steep, in many places, as a matter of course; but from the fact that Mr. G—— (who was mounted upon a young colt, that had never before been ridden, and had simply a piece of rope by way of bridle) trotted down most of the declivities, it may be inferred that the grade is not so very steep.

The first three or four miles beyond Ray’s, to the summit of first ridge, is all up hill; nearly 1,700 feet in altitude being gained in that distance, or 2,268 feet above the level of the sea, Ray’s being 617.

There are few places in all California where a more magnificent view can be obtained, than the one seen from this ridge. The whole valley of Russian River lies like a map at your feet, extending from the south-east and south, where it joins Petaluma Valley, clear round to the north-west. The course of the river can be traced for miles, far away, alternately sweeping its great curves of rippling silver out into the opening plain, or disappearing behind the dark masses of timber. From one end of the valley to the other, the golden yellow of the plain is diversified by the darker tints of the noble oaks. In some places they stand in great crowds; then an open space will occur, with perhaps a few scattered trees, which serve to conduct the eye to where a long line of them appears, like an army drawn up for review, with a few single trees in front by way of officers; and in the rear a confused crowd of stragglers to represent the baggage train and camp followers. Here and there, among the oaks, the vivid given foliage and bright red stems of the graceful madrone, and on the banks of the river can be seen the silvery willows and the dusky sycamores.

The beauty of the plain is still more enhanced by the numerous ranches, with their widely extending fields of ripe grain and verdant corn.

Beyond the valley is the long extending line of the Coast Mountains. The slanting rays of the declining sea were overspreading the mysterious blue and purple of their shadowy sides with a glorious golden haze, through whose gauzy splendor could be traced the summits only of the different ranges—towering one above the other, each succeeding fainter than the last, until the indescribably fine outline of the highest peaks, but one remove, in color, from the sky itself, bounded the prospect.

Toward the south-east, we could see Mount St. Helen’s, and the upper part of Napa Valley. St. Helen’s is certainly the most beautiful mountain in California. It is far from being as lofty as its more pretentious brethren of the Sierra Nevada, and by the side of the great Shasta Butte it would be dwarfed to a mole-hill; but its chaste and graceful outline is the very ideal of mountain form. There is said to be a copper plate, bearing an inscription, on the summit of this mountain, placed there by the Russians many years ago.

Away off, toward the south, we could discern that same old fog, still resting, like a huge incubus, upon San Francisco bay. Its fleecy billows were constantly in motion—now obscuring, now revealing the summits of different peaks, which rose like islands out of the sea of clouds. Above, and far beyond the fog, the view terminated with the long, level line of the blue Pacific, sixty or seventy miles distant.

From the point where we have stopped to take this extended view (too much extended, on paper, perhaps the reader will think), the horses climbed slowly up the steep ascent, leading to a plateau, on the northern side of a mountain, which has received no less than three different names. As it is a difficult matter, among so many titles, to fix upon the proper one, we will enumerate them all, laid the reader can take his choice. The mountain wag first called “Godwin’s Peak,” in honor of—there, G——, the cat’s out of the bag! your name has got into print, in spite of our endeavors to keep it out. With characteristic modesty, Mr. G—— declined the honor which the name conferred upon him, and it was changed by somebody or other to “Geyser Peak;” but, for some unknown reason, this name also failed to stick, and somebody else came along and called it “Sulphur Peak.” Both the latter names are inappropriate, for there are no Geysers nor no sulphur within five miles of the mountain. G., we are afraid you will have to endure your honors, and stand godfather to it.

The “Peak” rises to the height of three thousand four hundred and seventy-one feet above the level of the sea, and its sides are covered, clear to the summit, with a thick growth of tangled chaparal. From here, the trail runs along the narrow ridge of the mountains, forming the divide between “Sulphur Creek” (an odious name for a beautiful trout stream) and Pluton River. The ridge is called the “Hog’s Back”—still another name, as inappropriate as it is homely. The ridge much more resembles the back of a horse which has just crossed the plains, or has dieted for some time on shavings, than that of a plump porker. From the end of this ridge the trail is quite level, as far as the top of the bill, which pitches sharply down to the river, and at the foot of which the Geysers are situated.

When about two-thirds of the way down the hill, the rushing noise of the escaping steam of the Great Geyser can be heard; but, unless the stranger’s attention was called to it, he would mistake the sound for the roaring of the river. About this time, too, is recognized the sulphurous smell with which the air is impregnated.

Just as the traveller begins seriously to think that the hill has no bottom, the white gable end of the hotel, looking strangely out of place among its wild surroundings, comes unexpectedly into sight.

Upon awakening, on the following morning, it was a difficult matter to convince ourselves that we had not been transported, while asleep, to the close vicinity of some of the wharves in San Francisco, there was such a powerful smell of what seemed to be

GEYSER SPRINGS HOTEL. |

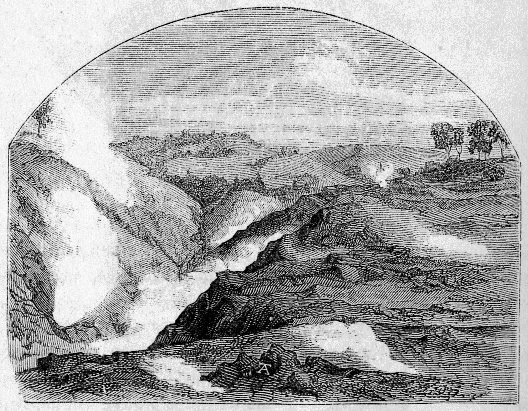

The view of the Geysers, from the hotel, is a very striking one, more especially in the morning, when the steam can be plainly seen, issuing from the earth in a hundred different places; the numerous columns uniting at some distance above the earth, and forming an immense cloud, which overhangs the whole cañon.

As the sun advances above the hills, this cloud is speedily “eaten up,” and the different columns of steam, with the exception of those from the Steamboat Geyser, the Witches’ Cauldron, and a few others, become invisible, being evaporated as fast as they issue from the ground.

Breakfast disposed of, Mr. G. kindly offered to conduct us to the different springs. The trail descends abruptly from the house, among the tangled undergrowth of the steep mountain side, to the river, some ninety feet below. We passed on the way the long row of bathing-houses, the water for which is conveyed across the river in a lead pipe, from a hot sulphur spring on the opposite side.

The unearthly-looking cañon, in which most of the springs are situated, makes up into the mountains directly from the river. A small stream of water, which rises at the head of the cañon, flows through its whole length. The stream is pure and cold at its source, but gradually becomes heated, and its purity sadly sullied, as it receives the waters of the numerous springs along its banks.

GEYSER CANON. |

Hot springs and cold springs; white, red, and black sulphur springs; iron, soda, and boiling alum springs; and the deuce only knows what other kind of springs, all pour their medicated waters into the little stream, until its once pure and limpid water—like a human patient made sick by over-doctoring—becomes pale, and has a wheyish, sickly, unnatural look, as it feverishly tosses and tumbles over its rocky bed.

A short distance up the cañon there is a deep, shady pool, which receives the united waters of all the springs above it. By the time the stream reaches here, its medicated waters become cooled to the temperature of a warm summer day, and the basin forms, perhaps, the most luxurious bath to be found in the world.

A few feet from this, there is a warm alum and iron spring, whose water is more thoroughly impregnated than any of the others.

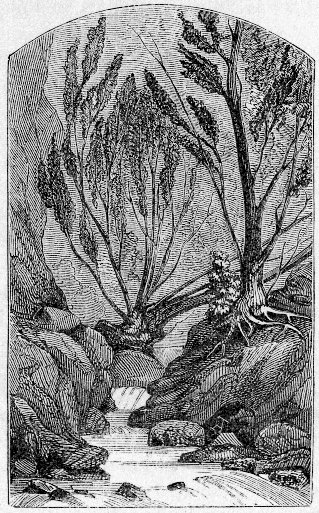

PROSERPINE’S GROTTO. |

A little way further up is “Proserpine’s Grotto,” an enchanting retreat among the wild rocks, completely surrounded and enclosed by the fantastic roots and twisted branches of the bay trees, and roofed over by their wide-spreading foliage. Glimpses of the narrow gorge above, with its numerous cascades, can be obtained through the openings of the trees; the whole forming one of the finest “little bits,” as an artist would call it, to be found in the country.

As we proceeded up the cañon the springs became more numerous. They were bubbling and boiling in every direction. We hardly dared to move for few of putting one feet into a spring of boiling alum, or red sulphur, or some other infernal concoction. The water of the stream, too, was now scalding hot, and the rocks, all the crumbling, porous earth, were nearly as hot as the water. We took good care to literally “follow in the footsteps of our illustrious predecessor,” as he hopped about from boulder to boulder, or rambled along in (as we thought) dangerous proximity to the boiling waters. Every moment he would pick up a handful of magnesia, or alum, or sulphur, or tartaric acid, or Epsom salts, or some other nasty stuff, plenty of which encrusted all the rocks all earth in the vicinity, and invite us to taste them. From frequent nibblings at the different deposits, our mouths became so puckered up, that all taste was lost for any thing else.

In addition to these strange and unnatural sights, the ear was saluted by a great variety of startling sounds. Every spring had a voice. Some hissed and sputtered like water poured upon red hot iron; others reminded one of the singing of a tea-kettle, or the purring of a cat; and others seethed all bubbled like so many cauldrons of boiling oil. One sounded precisely like the machinery of a grist mill in motion (it is called “The Devil’s Grist Mill”), and another like the propeller of a steamer.

High above all these sounds was the loud roaring of the great “Steamboat Geyser.”* [*This Geyser is shown in the view of “Geyser Cañon.” It is the upper large column of steam on the left side of the cañon; the one below it, and nearer the spectator, is the “Witches’ Cauldron.” The foreground of the view is occupied by the “Mountain of Fire,” from which the steam issues by a hundred different apertures. ] The steam of this Geyser issues with great force from a hole about two feet in diameter, and it is so heated as to be invisible until it has risen to some height from the ground. It is highly dangerous to approach very close to it unless there is sufficient wind to blow the steam aside.

But the most startling of all the various sounds was a continuous subterranean roar, similar to that which precedes an earthquake.

We must confess, that when in the midst of all those horrible sights all sounds, we felt very much like suggesting to G—— the propriety of returning, but a fresh handful of Epsom salts and alum, mixed, stopped our mouths, and by the time we had ceased sputtering over the puckerish compound, the “Witches’ Cauldron” was reached. (See vignette.) This is a horrible place. “Mind how you step here,” said G——, as we approached it; and, with the utmost caution, we placed our tens in his tracks, that is, as much of them as we could get in.

The cauldron is a hole, sunk like a well in the precipitous side of the mountain, and is of unknown depth. It is filled to the brim with something that looks very much like burnt cork and water (we believe the principal ingredient is black sulphur). This liquid blackness is in constant motion, bubbling and surging from side to side, and throwing up its boiling spray to the height of three or four feet. Its vapor deposits a black sediment on all the rocks in its vicinity.

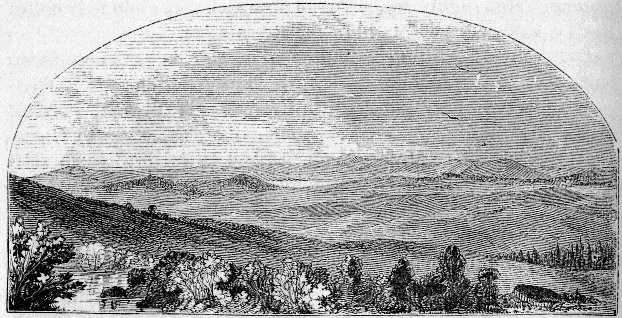

There are a great many other springs—some two hundred in number—of every gradation of temperature, from boiling hot to icy cold, and impregnated with all sorts of mineral and chemical compounds; frequently the two extremes of heat and cold are found within a few inches of each other. But as all the other springs present nearly the same characteristics as most of those already referred to, it would be but a tedious repetition to attempt to describe more. They are all wonderful. The ordinary observer can only look at them, and wonder that such things exist; but to the scientific man, one capable of divining the mysterious cause of their action, the study of them must be an exquisite delight. It is worth the traveller’s while to climb the mountains on the north side of the Pluton, for the fine view which their summits afford on every hand; toward the north, a part of Clear Lake can be seen, some fifteen miles distant. But, perhaps, the scene which

CLEAR LAKE, FROM THE RIDGE NEAR THE GEYSERS. |

Some people have said that California scenery is monotonous, that her mountains are all alike, and that her skies repeat each other from day to day. Believe them not, ye distant readers, to whom, as yet, our glorious California is an unknown land. The monotony is in their own narrow, unappreciative souls, not in our grand mountains, towering, ridge upon ridge, until the long line of the furthest peaks becomes blended with the dreamy haze that loves to linger round their summits. And the gorgeous glow of one sunrises, or the still more gorgeous green and orange, and gold and crimson, of our sunsets, reflect their heavenly hues upon dull eyes, indeed when they can see no beauty in them.

Next: Riffle-Box Waterfall • Contents • Previous: San Francisco

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/scenes_of_wonder_and_curiosity/california_geysers.html