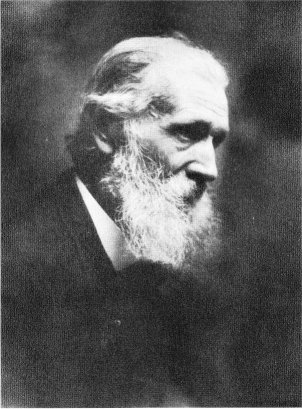

Photograph by W. E. Dassonville

JOHN MUIR

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Indians & Other Sketches > John Muir >

Next: Coulterville Road • Contents • Previous: Galen Clark

JOHN MUIR

Photograph by W. E. Dassonville JOHN MUIR |

tudents

and enthusiasts in one or even several

fields of nature have been many. But one alone has

had a passionate love for nature in every form and

mood and clime. John Muir stands apart as one

who saw beauty everywhere and felt a kinship and

reverence for all creation. With the magic touch of his pen, and in

words that can never die, he has interpreted nature with feeling

and understanding as no one else has done. Muir is unique, his observations

are scientifically accurate, his style is ever simple and

magnetic, and from his philosophy of life there radiates a contagious

atmosphere.

tudents

and enthusiasts in one or even several

fields of nature have been many. But one alone has

had a passionate love for nature in every form and

mood and clime. John Muir stands apart as one

who saw beauty everywhere and felt a kinship and

reverence for all creation. With the magic touch of his pen, and in

words that can never die, he has interpreted nature with feeling

and understanding as no one else has done. Muir is unique, his observations

are scientifically accurate, his style is ever simple and

magnetic, and from his philosophy of life there radiates a contagious

atmosphere.

The family emigrated from Scotland in 1849, when Muir was eleven years old, and settled in Wisconsin, northeast of Lake Mendota. Pioneer life was rigid, full of hardship and hard work. Comforts were few, money was scarce, and schooling was limited. Muir lived this pioneer life but his Scotch ancestry bequeathed to him values greater and more lasting than money. His was the priceless inheritance of integrity, patience, courage, and perseverance. His steadfastness of purpose overcame all obstacles. In his first twelve years in America he had but two months of schooling. His father’s stern, Scottish discipline sent every member of the family to bed immediately after prayers, which was about eight o’clock. Even though John was a young man of sixteen the rule could not be changed. He usually managed to steal a few minutes to read by candlelight in the kitchen, and this happened so often that his father, in exasperation, called to him to go straight to bed and get up in the morning if he must read. Nothing could have pleased him more. Five o’clock was the hour when everyone must get up and go to work. Henceforth he got up at one o’clock and thus gained four precious hours for reading and for work on his inventions. Nothing could dim his vision of the future. His aim was the State University at Madison, a town beautifully situated on the banks of Lake Mendota. The campus was on a well-rounded hill facing the State Capitol one and a half miles east. No landscape architect could add to the natural beauty of these grounds. Muir was charmed by them, and set forth from his home determined to attend the university. He rehearsed his background and limited schooling to the acting president, who received him with kindly welcome and understanding, and after a few weeks in the preparatory department, was enrolled as a freshman in the University of Wisconsin. Here he spent four years preparing himself for the university that has no buildings and the campus of which is the world. Muir had no degree from the University of Wisconsin; he had selected only the work that would further his study of nature. When in 1869 he left Wisconsin to enter the University of Life, it was with deep feeling and tearful eyes that he bade farewell to his alma mater.

The Sierra Mountains had long lured him and he set out for the Pacific Coast. When he arrived at San Francisco, he immediately asked the way to Yosemite. A walk of a hundred and fifty miles or more offered no obstacle. He shouldered his pack and set forth. In an open space near the foot of Yosemite Falls he built his cabin. It was a picturesque spot amid the pines and cedar and cottonwood trees. Tall growing brakes and great clumps of azaleas surrounded the cabin, and the Yosemite Falls poured its waters at his door. Muir says in a letter to one of his friends: “This cabin, I think, was the handsomest building in the Valley and the most useful and convenient for a mountaineer. From Yosemite Creek, where it first gathers its beaten waters at the foot of the falls, I dug a small ditch and brought a stream into the cabin, entering at one end and flowing out the other with just enough current to allow it to sing and warble in low, sweet tones, delightful at night while I lay in bed. The floor was made of rough slabs nicely joined and embedded in the ground. In the spring, the common pteris ferns pushed up between the joints of the slabs, two of which, growing slender like climbing ferns on account of the subdued light, I trained on threads up the sides and over my window in front of my writing desk in an ornamental arch. Dainty little tree frogs occasionally climbed the ferns and made fine music in the night, and common frogs came in with the stream and helped to sing with the Hylas and the warbling, tinkling water. My bed was suspended from the rafters and lined with libocedrus plumes, altogether forming a delightful home in the glorious valley at a cost of only $3 or $4 and I was loth to leave it.” For eleven years this cabin was Muir’s home. Here he enjoyed the aloneness that such surroundings make possible and the solitude that brings wealth of life to him who knows how to use it. From this cabin he went forth for days or weeks or months at a time to explore the Sierra. His needs were few; his small pack held notebook, tea, and biscuits, but rarely a blanket. Nature provided in season, fruits, edible roots, and nuts.

Muir’s first contact with Yosemite Valley and the High Sierra completely fascinated him. Their solitude brought joy and gladness. He writes (My First Summer in Sierra, 1869, p. 61): “Oh, these vast, calm, measureless mountain days, inciting at once to work and to rest. Days in whose light everything seems equally divine, opening a thousand windows to show us God. Nevermore, however weary, should one faint by the way who gains the blessing of one mountain day.” These mountains lured him increasingly throughout his life. He traveled widely but the Sierra was his home. During his first summer in this region he herded sheep for a rancher. The money he received was no doubt acceptable but his observations on sheep grazing gave him first-hand knowledge of the destruction of plants and shrubs and mountain meadows. When later his articles on this subject appeared in papers and magazines, the nation was aroused to value and guard its Yosemite, for here was one who spoke with authority. The people as well as the government were made aware of the exploitation of their parks.

The need of money recalled Muir to his Yosemite cabin long before the snows of winter threatened. Here he replenished his purse by working at the saw mill for J. M. Hutchings. It was here that Le Conte, the elder, met Muir in August, 1870. Le Conte tells of the meeting thus: “Today to Yosemite Falls—stopped a moment at the foot of the falls, at a saw mill to make inquiries. Here found a man in rough miller’s garb, whose intelligent face and earnest, clear blue eyes excited my interest. After some conversation, discovered that it was Mr. Muir, a gentleman of whom I had heard much from Mrs. Prof Carr and others. He had also received a letter from Mrs. Carr, concerning our party, and was looking for us. . . . I urged him to go with us to Mono . . . [we] learned from Mr. Muir that he would certainly go to Mono with us. We were much delighted to hear this. Mr. Muir is a gentleman of rare intelligence. . . . A man of such intelligence tending a saw mill! —not for himself but for Mr. Hutchings. This is California!”

No place could have been more fitting for these two lovers of nature to meet than Yosemite. It was Le Conte’s first summer in the Sierra and Muir led him and his party over the trail that he had blazed the year before. That tourist guiding was neither interesting nor remunerative to Muir is easily understood; few could comprehend their guide. Muir was not a recluse, however, but responded quickly to understanding people and enjoyed their friendship. Such men as Asa Gray, Professor J. D. Butler, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Louis Agassiz, valued the rare opportunity of his leadership and companionship. He describes his meeting with Emerson* [*Bale’s Life and Letters of John Muir, vol. I, pp. 235-255.] thus: “Emerson, Agassiz, Gray—these men influenced me more than any others. Yes, the most of my years were spent on the wild side of the continent, invisible, in the forests and mountains. These men were the first to find me and hail me as a brother. First of all, and greatest of all, came Emerson. I was then [May, 1871] living in Yosemite Valley as a convenient and grand vestibule of the Sierra from which I could make excursions into the adjacent mountains. I had not much money and was then running a saw mill that I had built to saw falling timber for cottages.

“When he came into the valley I heard the hotel people say with solemn emphasis, ‘Emerson is here.’ I was excited as I had never been excited before, and my heart throbbed as if an angel direct from heaven had alighted on the Sierran rocks. But so great was my awe and reverence, I did not dare to go to him or speak to him. . . . I wrote him a note and carried it to his hotel [Leidig’s] telling him that El Capitan and Tissiack demanded him to stay longer.

“The next day he inquired for the writer and was directed to the little saw mill. He came to the mill on horseback . . . and inquired for me. I stepped out and said, ‘I am Mr. Muir.’ . . . Then he dismounted and came into the mill. I had a study attached to the gable of the mill, overhanging the stream, into which I invited him, but it was not easy of access, being reached only by a series of sloping planks roughened by slats like a hen ladder; but he bravely climbed up and I showed him my collection of plants and sketches drawn from the surrounding mountains, which seemed to interest him greatly, and he asked many questions, pumping unconsciously.

“He came again and again, and I saw him every day while he remained in the valley, and on leaving I was invited to accompany him as far as Mariposa Grove of Big Trees. I said, ‘I’ll go, Mr. Emerson, if you will promise to camp with me in the grove. I’ll build a glorious camp fire, and the great brown boles of the giant Sequoias will be most impressively lighted up, and the night will be glorious.’ At this he became enthusiastic like a boy, his sweet perennial smile became still deeper and sweeter, and he said, ‘Yes, yes, we will camp out, camp out.’ And so next day we left Yosemite and rode twenty-five miles through the Sierra forests, the noblest on the face of the earth. . . . The colossal firs, Douglas spruce, Libocedrus and sugar pine, the kings and priests of the conifers of the earth, filled him with awe and delight.”

But Emerson did not camp out with Muir. He was in the keeping of his friends and they were afraid of the “night air” and insisted he go to his hotel in the Valley. As they mounted and rode away Emerson lingered in the rear. On the crest of the hill he stopped and turned his horse. Then took off his hat and waved a last good-bye to Muir standing alone at the edge of the grove. It was the last time that Muir saw Emerson. Muir confesses to a feeling of loneliness as Emerson disappeared from view—not the loneliness for someone to talk with, but the longing to share a joy that can find no expression in words. Emerson, he had thought, would love the mountains even as he did himself; he would be eager to spend a night amidst Sequoias lit up by a glorious camp-fire; he would be charmed by the music of the wind playing in the trees; he would enjoy nature wholly and fully as did Muir himself It was this disappointment that for the moment made him lonely.

Even if he had not been past his prime, Emerson could not have entered into the joys of nature as had Muir. Those who explore beyond the reach of others are beacons that inspire many to enter new adventures. Aloneness is the price that great men pay to stand upon the heights.

Muir’s wanderings in the Sierra were over uncharted regions, but many have followed the trail of his footsteps. His path from Yosemite to Mount Whitney, America’s highest mountain peak, has become a well-worn trail. Shortly after his death it was marked by a boulder bearing the inscription—“John Muir Trail—1917.” In the summer of’ 1933 the Sierra Club, of which John Muir was president from its organization in 1892 until his death in 1914, dedicated to his memory the recently completed shelter-hut on Muir Pass, 12,000 feet in elevation, built for the protection and safety of mountain travelers. It is constructed of flat stones and is shaped like a beehive and consists of one large room with an ample fireplace. Fifty members of the Sierra Club stood in this room at the dedication in July, 1933. A bronze plaque set into the structure of the hut bears the inscription: “To John Muir, lover of the Range of Light, this shelter was erected through the generosity of George Frederick Schwartz, 1931, Sierra Club, U. S. Forest Service.” Muir was once asked if there would be continued need of the Sierra Club. His answer seems fitting for the walls of the shelter hut. “So long as greed and wrong exist in the mountains, so long must the fight against these evils be carried on by the Sierra Club.”

Muir knew the Sierra, its glaciers and gorges, its forests, lakes, and mountain meadows. He explored the head waters of the Tuolumne and in Hetch Hetchy Valley he saw a second Yosemite not less beautiful than the first. He was quick to see the ruin that followed the grazing sheep, “hoofed locusts,” herded through the mountain meadows even to the glacier’s edge. Not only did they crop close but they uprooted plants and shrubs, changing flowering meadows into barren wastes. In denuding the mountainside the lumberman was destroying not only the trees, but was ruining in a day landscapes that nature through long ages had sculptured. Muir lived in the mountains and understood them. His cry and battle for conservation came from clear seeing and deep feeling.

His fight for the creation of a Yosemite National Park was accomplished mainly through his articles published in the Century Magazine. In 1864 the Federal Government ceded Yosemite Valley, together with a tract running a mile back from the rim, and also the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees, to the State of California. The State appropriation for the care and maintenance of the park was so limited that commissioners and guardian were underpaid—and often not paid at all. Herding, Lumbering, and Mining were carried on until the waterfalls of the Valley were threatened. The headwaters of the streams feeding the falls were not included in the State Park grant. It became a growing burden on Muir’s mind and heart that these headwaters and other mountain tracts must be set aside in a National Park if Yosemite Valley was to be preserved. In 1889, Robert Underwood Johnson, associate editor of the Century Magazine, met John Muir in San Francisco and accompanied him to Yosemite and into the Sierra. At their Soda Spring campfire, Johnson remarked that he had not seen any of the mountain meadow gardens so vividly described by Muir in the articles that had been published in the Century. Muir told him that the “hoofed locusts” not only ate everything in sight but also pulled up the roots of plants and shrubs, leaving the meadows barren. The melting snow, with no underbrush to hold it, runs in torrents in the springtime and leaves the falls dry in summer. It was obvious that if Yosemite Valley was to be preserved the State Park must be greatly enlarged and made a National Park.

Johnson* [*Remembered Yesterdays, R. U. Johnson, p. 288.] says: “I told him [Muir] if he would write for the Century two articles, the first on Treasures of Yosemite, to attract general attention, and the second on Proposed Yosemite National Park, . . . the boundaries of which he should outline . . . that I would go to Congress . . . and advocate its establishment . . . and that in my judgment it would go through. Muir . . . wrote the articles. . . . The next summer [1890], I appeared before the House Committee, a bill was drafted on the lines of Muir’s boundaries. . . . October 1, 1890, the Yosemite National Park became a fact. “It was put under military control and sheep grazing was no longer permitted within the park boundaries.

Regarding Yosemite Valley Johnson says: “The neglect of the Valley under State control had for years been a public scandal. . . . Portions of the beautiful wild undergrowth of the Valley had been turned into hay fields, so that there might be fodder for the horses that are employed in taking visitors up the trails. . . . In order that one of the little inns should have as good a vista as the State hotel, the Stoneman House, a lane had been cut to the Yosemite Falls, and the great trees thus slaughtered had been left lying where they fell.” Yosemite State Park was surrounded by Yosemite National Park; the former was under State control, the latter under Federal. Naturally, the management of these two areas was a complicated matter and the results were more and more unsatisfactory.

With other interested persons, Muir again led the fight. Johnson continues: “This fight for the better management of Yosemite went on for many years, always under the uncompromising leadership of Muir. It soon took the form of a movement for the retrocession of the Valley to the National Government. . . . Muir led the fight in California, and when the time came, went to Sacramento . . . and showed himself the most practical of politicians. . . . The bill was finally passed. . . . Writing July 16, Muir says: ‘Yes, my dear Johnson, sound the loud timbrel and let every Yosemite tree and stream rejoice! You may be sure I knew when the big bill passed. . . . You don’t know what an accomplished lobyist I’ve become under your guidance. The fight you planned by that Tuolumne campfire seventeen years ago is at last fairly, gloriously won, every enemy down derry doon’.” August 1, 1906, Headquarters for Yosemite National Park was moved from Wawona to Yosemite Valley, located on the present site of Yosemite Lodge, and was called Fort Yosemite.

Muir also led the fight to restrain San Francisco from getting its water supply from Yosemite National Park by damming the Tuolumne river at Hetch Hetchy, the “Tuolumne Yosemite,” as Muir called this valley. The bill granting water rights to San Francisco was introduced by Representative Raker and passed the House in September, 1913. Hope was centered on the Senate, and even if the Senate should pass it, great assurance was felt that the President would veto the bill. The Senate did pass the bill in December, 1913, and President Wilson signed it. Muir was downcast but he was also relieved. Writing to a friend, he said: “I’m glad the fight for the Tuolumne Yosemite is finished. It has lasted twelve years. Some compensating good must surely come from so great a loss.”

No one more zealously and untiringly championed conservation in all its aspects than did Muir, yet it is not as a conservationist that he is best known. The charming little bell-like Cassiope is known as John Muir’s White Heather. His love for mountain leas, flowering hillsides, and bloom-covered deserts made him acquainted with plants and flowers, yet we do not think of him as a botanist. Neither was he a zoologist nor ornithologist, though he knew animals and birds. His description of the saucy, daring, sprightly Douglas squirrel thrills to the core. It is at once a contribution to literature and a rare study of nature. He knew birds from early childhood and increased his acquaintance wherever he met them. His description of the water ouzel is a classic and has made this drab little bird widely known and admired. Besides, Muir was a geologist and geographer.

His observations on glaciers and erosion are valuable contributions to these fields. (Address by C. R. Van Hise, President of the University of Wisconsin, December, 1916, at the unveiling of a bust of John Muir.) President Van Hise says: “His explorations there [in Alaska] represent the most important part of his geographic work; they added much to the knowledge of the Alaskan coast. A number of important inlets were mapped, the chiefest of which is Glacier Bay. In the latter was discovered the majestic glacier which bears Muir’s name, a mighty stream, of ice, in its broadest part twenty-five miles wide and having two hundred glacial tributaries. As compared with this, the greatest Alpine glacier is a pigmy. Muir’s close observations upon the motion and work of glaciers, first the small ones of the Sierra, and later the mighty ones of Alaska, were important contributions to the knowledge of the great agents of erosion. . . . John Muir’s explorations of the Sierra and in Alaska were done alone. He had no pack train; his entire outfit he carried on his back. A sack of bread and a package of tea for food (as long as they lasted), his scientific instruments and his note books, constituted his load; . . . climbing in the mountains by one’s self, as did Muir, is one of the most exacting of the physical arts. . . . To explore glaciers alone, and especially unknown glaciers, requires agility and endurance, constant skill, steady coolness, and never-failing watchfulness. To jump innumerable crevasses, to cross those too wide to jump on ice bridges, are a severe strain upon the nerves of any man; and yet Muir . . . worked day after day alone on the vast glacier that bears his name.”

Muir traveled in Australia, New Zealand, India, Africa, Russia, Switzerland, South America, and Alaska, always as a student of nature, whose every form was to him lovely. But trees rose above all; to him they were nature’s most beautiful expression. He says of Mount Hoffman, that the traveler will find the lower slopes “plushed with chapparel rich in berries and bloom, a favorite for bears. The middle region is planted with the most superb forest of silver fir I ever beheld.”

Muir is known more widely today than ever before. His name is honored throughout the world. His spirit has thrilled and inspired and recreated thousands who have followed his trails to the mountains. Grateful appreciation has preserved his name in Muir Hut, Muir Trail, and Muir Pass, over which thousands hike each year. On the Lost Arrow trail in Yosemite Valley the spot where his cabin once stood is marked by a large boulder. The plaque bears the inscription (Our National Parks, John Muir, p. 56): “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings, Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.”

In presenting to the United States a forest of magnificent redwoods, Senator and Mrs. Kent requested that it bear the name “Muir Woods.” On the campus of the University of Wisconsin, where Muir spent his college years, a rise of ground overlooking Lake Mendota was dedicated in 1915 as Muir Knoll. In the State Historical Museum, at Madison, Wisconsin, no object attracts more interest than the almost human clock invented and constructed by John Muir in the sixties, and used by him while attending the University. At the hour set for rising it dumped its occupant out of bed. At a set time, a lever attached from the clock to his bookcase, brought a book from the shelf, placed it on the desk, opened at the lesson page, then returned it and brought down the next. A dainty butterfly in the New York Museum of Natural History is named for Muir who collected it on Mount Hoffman and sent it to Harry Edwards, who writes (Papilio, Vol. 6, p. 54): “I have named this exquisite species after my friend, John Muir, Thecla Muiri, who has frequently added rare and interesting species to my collection.” Recognition and appreciation of Muir’s life are expressed in honorary degrees conferred by colleges and universities. In 1896, Harvard conferred on him the degree of Master of Arts. The following year, 1897, the University of Wisconsin, proud of its alumnus, conferred on him her highest academic honor, the degree of Doctor of Laws. Yale, in 1911, conferred the degree of Doctor of Literature, and in 1913, the University of California conferred the degree of Doctor of Laws.

But the highest and final degree is conferred by the University of Life at no stated time or place. It is given without pomp or ceremony. All other degrees and titles become useless and fade away, as gradually and unconsciously the simple degree of Greatness is bestowed. The recipients are called Columbus, Huxley, Darwin, Linnaeus, Muir. They are the product of no school or locality. The Great belong to neither time nor place; they are universal.

As the interpreter of nature in every form and mood, Muir stands above the timberline and alone. His burning enthusiasm and the warmth and life in his expression draw all men irresistibly to , forest and mountain, waterfall and quiet stream. His descriptions of rocks and plants, of trees and animals, are lasting pictures of living individuals. Douglas squirrel, water ouzel, cassiope, silver firs and spruces—all are instinct with personality and life. “His talk about California trees and flowers was even more wonderful than his writing, and stenographers and desk-men used to invent errands to my room in order to listen to fragments of it,” says Bliss Perry, editor of the Atlantic. Today, in ever increasing numbers, men and women are following his guidance to an appreciation of the beauty and grandeur of things that are natural; they are learning to see and recognize in waters and rocks, plants and animals, storm and sunshine, the ever active forces that have made and are still making the world a never-ending story of beauty and delight. To everyone who catches something of his spirit, he interprets the mountain meadow, the roaring waterfall, and the quiet stream. Storm, wind and hail, thunder and lightning, were to him “a cordial outpouring of nature’s love.”

John Muir was born at Dunbar, Scotland, April 21, 1838. He died at Los Angeles, December 24, 1914. He is buried in the family plot on the Strenzel ranch near Martinez, California.

In 1930 the Muir Pilgrimage was inaugurated. Annually in April, the month of Muir’s birth, the federated women’s clubs of Alameda County, members of the Sierra Club, and others interested meet at the Strenzel Ranch. Under the great white-boled Eucalyptus tree standing near the entrance to the family burial lot a program is presented. Wreaths are placed upon the graves by Boy Scouts and Camp Fire Girls. Those who have walked and talked with Muir rehearse these precious hours. The presence of Muir’s oldest daughter, Mrs. Wanda Muir Hanna, adds much interest to the occasion. It is mainly through the efforts of Mrs. Linnie M. Wolfe that the pilgrimage is increasingly interesting and attractive in its program. In April, 1936 about three hundred pilgrims gathered at the Hanna Ranch near Martinez. Scotch Bag Pipers, in colorful plaids and kilts, played Scotch music and a descendant of Annie Laurie sang that favorite song. At the close of the program all join hands about the tree as they sing “Auld Lange Syne.” From the distant hills are heard the buglers’ taps. Slowly the Pilgrims depart.

Muir’s grave is a sacred spot. His spirit lives in the hearts of an ever widening number of those who are finding health and happiness in the out-of-doors where nature gives so freely from her well-springs and asks nothing in return.

Next: Coulterville Road • Contents • Previous: Galen Clark

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_indians_and_other_sketches/john_muir.html