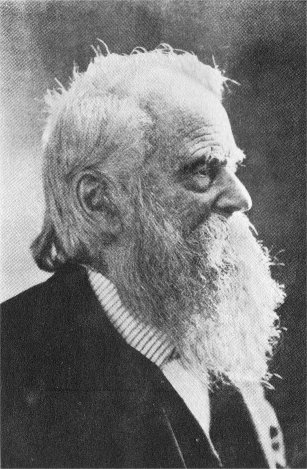

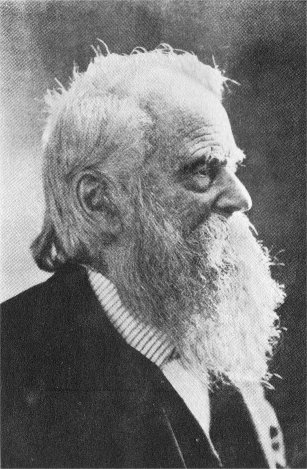

Photograph by Taber

GALEN CLARK

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Indians & Other Sketches > Galen Clark >

Next: John Muir • Contents • Previous: James Hutchings

GALEN CLARK

Photograph by Taber GALEN CLARK |

“GUARDIAN OF YOSEMITE”

he

pioneers of Yosemite are an intimate and interesting

part of its history. Galen Clark,

“Guardian of Yosemite,” came to California in 1853, two years

after the discovery of Yosemite Valley. For fifty-seven

years he was closely connected with the Valley

and adjacent region. In the family record book owned by his

nephew, L. L. McCoy, there is written in Galen Clark’s own hand:

“Galen Clark was born March 28th, 1814. A native of Dublin,

New Hampshire.” The following data are from letters and interviews

with his nephews, L. L. McCoy and A. M. McCoy, both of

Red Bluff, California. In 1836 Galen Clark settled in Waterloo,

Missouri. He was a cabinet maker by trade. Some years ago when

Mr. Clark was visiting in the home of L. L. McCoy he looked at a

chair with hickory bark bottom and remarked, “I made that set of

six chairs for your grandfather, Joseph McCoy, in Waterloo, Missouri,

in the winter of 1836-37.” In 1839 Mr. Clark married

Rebecca McCoy, daughter of Joseph McCoy. He lived in Missouri

until 1845 when, with his wife and three children, he moved to

Philadelphia. There, in 1848, his wife died, leaving an infant son

nine days old.

he

pioneers of Yosemite are an intimate and interesting

part of its history. Galen Clark,

“Guardian of Yosemite,” came to California in 1853, two years

after the discovery of Yosemite Valley. For fifty-seven

years he was closely connected with the Valley

and adjacent region. In the family record book owned by his

nephew, L. L. McCoy, there is written in Galen Clark’s own hand:

“Galen Clark was born March 28th, 1814. A native of Dublin,

New Hampshire.” The following data are from letters and interviews

with his nephews, L. L. McCoy and A. M. McCoy, both of

Red Bluff, California. In 1836 Galen Clark settled in Waterloo,

Missouri. He was a cabinet maker by trade. Some years ago when

Mr. Clark was visiting in the home of L. L. McCoy he looked at a

chair with hickory bark bottom and remarked, “I made that set of

six chairs for your grandfather, Joseph McCoy, in Waterloo, Missouri,

in the winter of 1836-37.” In 1839 Mr. Clark married

Rebecca McCoy, daughter of Joseph McCoy. He lived in Missouri

until 1845 when, with his wife and three children, he moved to

Philadelphia. There, in 1848, his wife died, leaving an infant son

nine days old.

Mr. Clark took his children, three boys and two girls, to relatives in Massachusetts, where they grew up and were educated. His oldest son, Joseph, was killed in the Civil War. The second son, Alonzo, graduated from Harvard in 1870, and in 1871 came to California to be with his father who was then keeping the hotel known as Clark’s Station, now Wawona. Alonzo died in 1874 and is buried in the Mariposa cemetery. Elvira, the oldest daughter, came west to see her father in 1870 and married Dr. Lee. They lived in Oakland, California where her father, Galen Clark, died on March 24, 1910. Ruth, the youngest daughter, remained in the East. Solon, the youngest son, was drowned at the age of nine years

While Galen Clark was living in the East he heard accounts of vast fortunes made by gold miners in California and determined to see the new Eldorado. He came by way of the Isthmus of Panama and in 1854 went to Mariposa, heralded for its rich discoveries. and there engaged in mining. In August, 1855, a party of twelve or fourteen from Mariposa and Bear Valley trailed into Yosemite. Galen Clark, a member of this party, was fascinated by the Valley and the mountain region surrounding it.

When exposure of mining injured his health and hemorrhages became serious he was forced to give up the work. Mr. Clark recalled the beautiful mountain meadows he had seen on his trip into Yosemite and in the spring of 1857 he went to the South Fork of the Merced, where the Mariposa Battalion had camped in 1851. Here, in one of the loveliest mountain meadows of the High Sierra. he made his home. It was half way along the trail leading from Mariposa to Yosemite Valley.

On the spot where the Wawona Hotel now stands, he built his log cabin, crude but not without charm. It had its shelf of rare books;Yosemite pictures were on its walls; a great fireplace with an ample supply of wood on either side made it an inviting place to stay for a day or a month. Mr. Clark’s training in cabinet work proved useful in these early mountain days and Clark’s Station became a haven of rest for tourists on the long trail. As host, cook, guide, scientist, and philosopher, Mr. Clark was a rare, never-to-be-forgotten pioneer. He looked a patriarch and grew more patriarchal every year. As travel increased, the cabin was enlarged and furnished with comfortable chairs and the best of beds. Tourists marveled at the abundance of excellent food. Add to that, Mr. Clark’s interesting personality, refreshing wit, wholesome philosophy, and his knowledge of trees, flowers, and animals, and can one wonder that Clark’s Station was known far and wide?

Financially, Mr. Clark was not successful. He gave freely of himself and spared no expense for the comfort and welfare of guests. In 1870 he took Edwin Moore as a partner and the Station became Clarke and Moore’s. The extensive repairs and additions that were made were too costly for a hotel dependent solely on the summer season tourists. In 1875 Washburn Brothers took over the station and changed the name to"Wawona.” It is still a delightful, restful hotel in a charming meadow.

The out-of-door life in the mountains completely restored Mr. Clark’s health, as his ninety-six years testify. When the tourist season was over he explored the surrounding country. He became acquainted with the Indians as well as with the flora and fauna of the region. While out hunting in 1857 he discovered the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees (Sequoia gigantea). This grove contains three hundred and sixty-five trees of great size, and innumerable seedlings preparing themselves for coming generations. Mr. Clark became a recognized mountaineer of the Yosemite region. John Muir writes: “Galen Clark was the best mountaineer I ever met, and one of the kindest and most amiable of all my mountain friends. His kindness to all Yosemite visitors and mountaineers was marvelously constant and uniform. . . . He was one of the most sincere tree lovers I ever knew.”

Mr. Clark was greatly impressed by his discovery of the Big Tree Grove. He would make these unknown trees accessible to the tourist, and known to the world. He blazed a horse trail from Clark’s Station to the grove and built a cabin, known as “Galen’s Hospice,” to be used as a place to rest or to stop overnight if cold or storm should overtake the traveler. Today a replica of the cabin stands on the original location and provides a museum for the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees.

The name “Clark’s Grove” was suggested for this grove but Mr. Clark shunned publicity. His retiring, modest personality could not accept the honor and he asked that, instead, it be named Mariposa Grove of Big Trees. A tree, 240 feet high and 21 1/2 feet in diameter, the one first seen by the discoverer, is named Galen Clark. The cairn close by was built by Mr. Clark.

To advertise the road and also to give tourists the thrill of knowing the bigness of these trees, the Yosemite Stage and Turn-Pike Company, in 1880 paid the two Scribner brothers $75 to cut a tunnel 8 feet by 27 1/2 feet and high enough for stage and passengers through one of the Big Trees. The tunneled tree was appropriately named “Wawona,” which in the Miwok Indian language, means “Big Tree.”

The advertisement brought returns and the route through the Mariposa Grove became popular. Driving through a tree with the stage was an interesting and thrilling experience. The photographer saw his opportunity; when the stage was almost through the tree it stopped; the camera man took the picture; the tourist gave orders for copies; and the stage drove on, and he awaited the next stage. Above the fireplace in the Yosemite Museum hangs a picture of one of the early stages driving through the Wawona Tree. In this picture Galen Clark sits with the driver. Tourists in no small numbers drive through this tree each season. It is today in good, healthy condition. Sufficient bark and living tissue for life and growth remained after cutting the tunnel. No other tree has been so widely known as Wawona, the tunneled tree. Pictured in school-books throughout the land the memories of thousands, once school children, recall the Wawona Tree.

Four Big Trees (Sequoia gigantea) have been tunneled. The Wawona Tree in the Mariposa Grove was tunneled in 1880. The California Tree, also in the Mariposa Grove, about one hundred yards east of the Grizzly Giant, was cut about 1895. The first of the four trees to be tunneled was the Dead Giant, in the Tuolumne Grove, cut in 1878. It was stumped 90 feet from the ground and entirely barked, thereby killing it—hence the Dead Giant. It will stand for centuries, a ghastly specter. The fourth tunneled tree, known as the Pioneer, is in the Calaveras Grove, and is the only one outside the boundaries of Yosemite National Park. The Wawona Tree still makes its appeal to the tourists of today. The other three tunneled trees are all but forgotten.

Due to Mr. Clark’s interest and efforts no other grove has so many well-known trees as the Mariposa Grove. The Fallen Monarch attracts tourists in numbers as great as if it still lived and stood among its fellows. Dr. Nicholas Senn, in his book National Recreation Parks, published in 1904 (p. 145), says: “Five years ago the Monarch of the Mariposa Grove of Sequoias . . . severed his connection with the soil that had nourished him so well and long and fell helpless, crushing through the branches of his loyal neighbors.”

The Mariposa Grove must have trembled when the giant Massachusetts fell in the spring of 1927. the tree is magnificent in its repose. Fire burned away much of its base. Road-building in the early years of Yosemite cut into its roots, which are wide-spreading rather than deep, thus lessening still further its hold on the earth. The eternal law of gravity gradually overcame every hold and the great Sequoia fell.

The Clothespin Tree, the Telescope Tree, and the Three Graces are well-known and are interesting in different ways. The Mather Tree, dedicated to Stephen T. Mather, first Director of National Park Service, whose valuable service, untiring efforts, and great generosity have made every citizen of our country his debtor, is a young Sequoia with its growth, power and usefulness in the future. The tree is symbolic of the vision that Mr. Mather had for the development of our national parks.

In respect to symmetry and beauty, the Alabama Tree has a place all its own. Fire has not scarred it, wind, snow, and hail have left its branches unbroken. Beautiful in form, vibrant with life, the Alabama Tree has an alluring charm.

To many, Grizzly is the most beloved of all Big Trees. In his book, Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California, published in 1862, J. M. Hutchings says (p. 148): “We measured one sturdy, gnarled old fellow, which, although badly burned, and the bark almost gone so that a large portion of its original size was lost, is nevertheless, still ninety feet in circumference and which we took the liberty of naming the ‘Grizzled Giant’.” In his article"New Sequoia Forests of California,” published in Harpers Magazine, November, 1878 (vol. 57, pp. 813-827), John Muir says: “The most notable tree in the well-known Mariposa Grove is the Grizzly Giant, some thirty feet in diameter, growing on the top of a stony ridge. When this tree falls, it will make so extensive a basin by the uptearing of its huge roots, and so deep and broad a ditch by the blow of its ponderous trunk, that, even supposing that the trunk itself be speedily burned, traces of its existence will nevertheless remain patent for thousands of years. Because being on a ridge, the root hollow and trunk ditch made by its fall will not be filled up by rain washing; neither will they be obliterated by falling leaves, for leaves are constantly consumed in forest fires; and if by any chance they should not be thus consumed, the humus resulting from their decay would still indicate the fallen Sequoia by a long straight strip of special soil, and special growth to which it would give birth. . . . The General Grant, of King’s River Grove, has acquired considerable notoriety in California as the biggest tree in the world, though in reality less interesting and not so large as many others of no name. . . . A fair measurement makes it about equal to the giant . . . which it also resembles in general appearance.”

Fire and storm have left deep scars on the Grizzly Giant of the Mariposa Grove. It has a lean of twenty-four feet and the never-failing force of gravity will slowly and surely lay it down. When, no one knows.

No other pioneer was connected with Yosemite in so many ways, for so long a time, and so intimately as Galen Clark. The grant from the Federal Government setting aside Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees for a State Park, was approved by President Lincoln, June 30, 1864. Frederick F. Low, Governor of California, appointed Galen Clark on the commission to govern these two tracts. Later he was appointed Guardian of the newly made Park. His long and valued service in this position, which he held for twenty-four years, earned for him the title “Guardian of Yosemite.” His cordial and generous hospitality, his never-failing kindness to all tourists, gradually and permanently bestowed on him the more intimate title “Beloved Man of Yosemite.”

In 1890 Yosemite became a National Park, but Galen Clark continued to make the Valley his summer home for nearly twenty years. He brought the first wagon into Yosemite Valley. Charles Tuttle, the first white boy born in Yosemite, rehearsed the sensation created by this event: “I was a boy of eight or nine years when the first wagon was brought into the Valley. Galen Clark had it packed in on mule back. I had never been out of the Valley and had never seen a wagon. Everybody was interested to see it assembled. When all was in readiness three or four days were given to celebrate the event and everybody living in the Valley had a free ride; I will never forget those days! They were wonderful!” In 1889 John Muir writes: “I find Old Galen Clark also. He looks well and is earning a living by carrying passengers about the Valley.” The old wagon is an interesting and prized relic in the Yosemite Museum.

Throughout his years Galen Clark was sought by tourists in order that they might hear the experiences and tales of this pioneer, who was not without wit and a keen sense of humor. His niece, Florence McCoy Sheffield, told the following to the writer: “Four women tourists met my Uncle Galen in Yosemite and were welcomed to his cabin. To their request to hear of his life in Yosemite he replied that he would tell them of his experiences if they would indicate what they were interested in hearing. With one accord came, “We want to hear all about everything, you just go ahead!” With a benign smile and a twinkle his eyes never lost he said: ‘I’m no artesian well, but I can be pumped. You just go ahead’.”

Galen Clark is the author of three small books, all of which were written when he was past ninety years of age: The Big Trees of California, 1907, 104 pages. Illustrated. Indians of the Yosemite Valley and Vicinity, 1904, 110 pages. Illustrations by Chris Jorgensen. The Yosemite Valley, Its History, 1910, 108 pages. Illustrated.

On the Lost Arrow Trail there is an open space that frames in the Yosemite Falls. Here is the John Muir plaque that marks the spot where once his cabin stood, and a few feet away stands the Memorial Bench that in 1911 was dedicated to Galen Clark.

When Washburn Brothers took over Clark’s Station in 1875, they gave him the freedom of their hotel for the remaining thirty-five years of his life. He was a frequent and ever welcome guest. Upon his death in Oakland at the home of his daughter, Elvira Clark Lee, on March 24, 1910, at the age of ninety-six years, Washburn Brothers asked the privilege of bearing all funeral expenses. They took the body to Yosemite where, more than twenty years before, Galen Clark had selected a burial spot in the old cemetery. In each corner he had planted a young Sequoia taken from the grove that he had discovered in 1857. In the Merced Star of April 7, 1910, we read that the girls and boys of Yosemite Valley, dressed in white, attended the funeral services in a body. Each carried a wreath of evergreen and cherry blossoms tied with purple ribbon. One by one the wreaths were laid about the casket. The pallbearers placed their boutonnieres upon the casket. The body of Galen Clark was lowered into the grave that he himself had dug a few years earlier. A rough granite boulder, upon which he had chiseled his name in 1890, is his headstone.

The many tourists interested in the pioneer days of Yosemite have worn a path to the grave of Galen Clark—“Beloved Man of Yosemite.”

Next: John Muir • Contents • Previous: James Hutchings

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_indians_and_other_sketches/galen_clark.html