[click to enlarge]

the workaday world far behind

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Tales & Trails > 6. Traveling the Trails >

Next: Indian Legends • Contents • Previous: Trees of Yosemite

WHEN YOU start collecting road maps and tracing High Sierra Camps with a blue pencil, you might just as well wind the office clock, tear a week or a month off the calendar, and be on your way. For, to all intents and purposes, you have begun traveling the trails of Yosemite.

That is the magic of maps. Cause and effect become blurred, and it is only a step from following a dotted black line across white paper, looking like a fever or population chart, to jogging along a mountain trail, skirting the skyline of the Sierras, or sauntering down by some still, forgotten lake.

The call of the trail is irresistible, as Horace Albright points out in his chapter on “Hikers” in “Oh, Ranger!” “Some lingering spark from the days when our ancestors were trail-blazing flares up in each of us once or twice or thrice a year, and there burns that longing for the winding trail that leads now over mountain passes, now through fragrant forests, now by rushing waters, or past ramparts of rocks.”

Hikers, like all Gaul, they divide into three parts. There are the mountain climbers, who come either in bevies and clubs, or as free-lances, and adopt some mountain temporarily and cannot rest until they have scaled its peak, before going on to conquer new heights. There are the nature-lovers who don’t care a hang what is on top of the mountain, who are lured by a trail not because it leads to the earth’s high spots, but because it winds through woods and meadows and dells, across carpets of blossoms where wild flowers and wild animals can be stalked and studied at leisure. And “there is the plain and lowly hiker, with his camera in his hand and perspiration on his brow, who outnumbers all the aforementioned gentry of the trail something like four to one. They are the ordinary folk, sick of the sight of old brick walls, longing for a look at the wilderness, hoofing it along a narrow path for no other reason than the sheer fun of it. All he asks is a well-marked trail, leading somewhere at the end of the day. All the service he demands is an extra pair of socks, a roll of adhesive tape, a big bite of lunch, and a camera to shoot the stag which stares pop-eyed at him from the azaleas.”

After the hikers go the trail-riders, those aristocrats of the mountains who travel first class where travel de luxe is still aboard the broad back of a trail pony or mountain mule. As they pass the plodding hikers along the way, each feels a peculiar superiority to the other, and each a sneaking envy. For as David Curry used to say, when he announced about the Curry campfire that reservations were being made for horses leaving in the morning for the Glacier Point trail, “Those of you who walk will probably wish you had ridden, and those of you who ride will wish you had walked.”

But they are all brothers under the dust, and it is a great fellowship that camaraderie of the trail. When they gather about the same board at night, hiker, trail-rider, or motorist (low caste though he is!) or share their bread and campfire in some sequestered spot, world politics and economic depressions are of little importance as compared to the number of miles covered that day, the steepness of the climb planned for the morrow, or the number and variety of wild flowers blooming along the Pohono trail at that time of year.

Motorists, too, have a fraternity of their own in the Sierras, with an A and B grading. Those B motorists who whiz-bang through the country, boasting of having made the Lee Vining grade in high, or of having covered more territory in less time than anyone in camp, are not popular with the “Poison-Oakers,” or experienced mountaineers, who have just humped over some stupendous pass under their own steam. But that great motor caravan of campers who use roads as they are intended to be used, as a means of getting into the wilderness to enjoy it at leisure, are admitted into the clan of trail buddies on an almost equal footing. Only circumstances set them a little below the one hundred per cent hikers, who, of course, really own the mountains.

The old cry still echoes through the canyons that automobile roads are spoiling the wilderness and ruining Americans for walking. Yet for every mile of highway which penetrates those wildernesses two miles of trail are made more accessible. As roads push farther and farther into the forests, trails push ahead of them, opening new hinterlands of beauty which have never been explored. Just look at the map of Yosemite. In spite of the six hundred miles of trail which crisscross the Park, consider the thousands of acres of grandeur which have not yet been scratched. So that great and growing company of trail-trekkers will be safe for many years to come. Uncle Sam is attending to that. For he has limited the number of roads which can be built into any National Park, while increasing the trail projects. The balance of beauty still lies with the hiker, and he has only to shoulder his pack and swing up the trail to lose himself in an hour in as profound a solitude as the Lord ever created in his six days of world-making.

Yet to anyone who feels keenly on this subject of roads, I recommend just one trip over the new highway into Yosemite by way of Wawona and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees. There’s a road which is, in reality, a glorified trail. It winds its way in broad curves through one of the finest stands of timber in America, and its approach to Yosemite Valley is without equal. You emerge from a mile-long mountain tunnel, a wonder in itself, and the Valley bursts upon you. One moment it is not there, and the next it is, in all its entirety. It is like the first view of Death Valley from Dante’s Point, or the sudden stepping out upon the rim of the Grand Canyon. You have no preparation, no fugitive glimpses. There it is, abrupt and breath-taking. And it is a grand way to step onto the Yosemite stage for the first time, very much as it happened to those first discoverers of the Valley who first saw it from practically the same vantage-point. It is a moment you will be glad to store in the archives of memory. And one which may convert you to road-making.

Before you start traveling the trails in Yosemite, it is a good idea to visit the Museum in the Valley and study the relief map of the Park. You will find it interesting to trace your route over mountain and through canyons, beside rivers and across meadows. And you will go with a much more vivid idea of the sort of country you are planning to discover. Then, when you return, visit the map again and you will find that impersonal black line leading across ridges and dipping into hollows has taken on new meaning, conjuring up pictures of scalloped peaks against a sunset sky, wooded valleys filled with the sound of rushing waters,

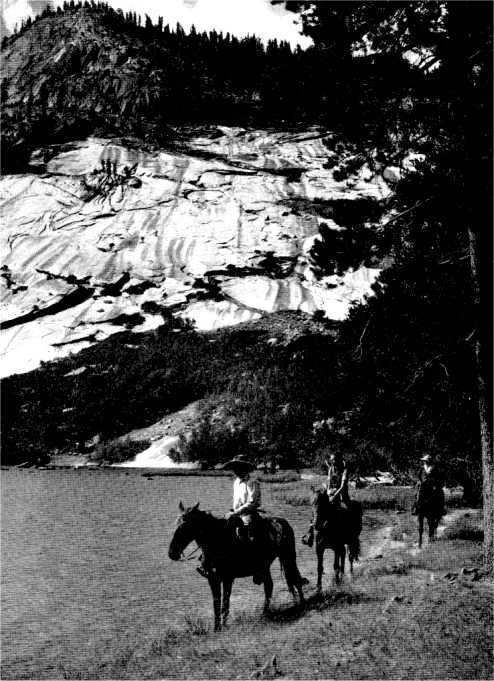

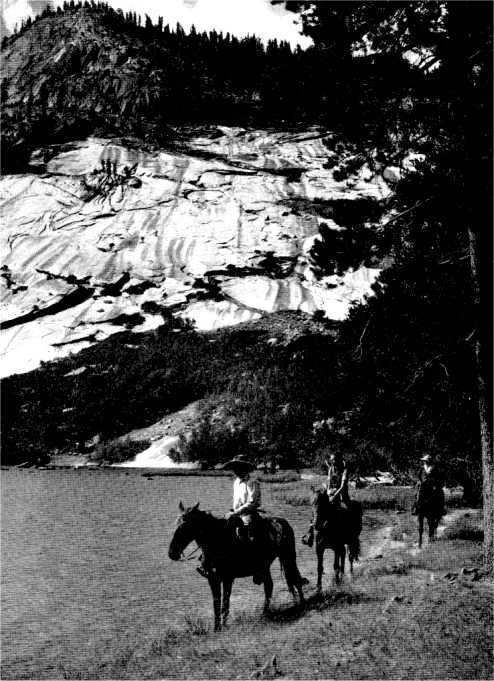

[click to enlarge] |

|

At Merced Lake trail-riders leave

the workaday world far behind |

Up there in the Sierras time is the coin of the realm. You are rich or poor, not according to the dollars, but to the days and the nights you have to spend. So hoard your hours like a miser, till you arrive, then spend them like a mountain millionaire, paying out a day to stroll across the roof of the world, an hour to lie beneath a tree which has taken three thousand years in the growing! Budget your time, so that none of it is squandered, then spend like a prodigal, and your interest will be compounded every year for the rest of your life.

You will have to allow quite a bit of time for the Valley itself. Before you leave to skirmish on high, explore the Indian Caves under the Royal Arches, where the first and only Yosemite Indian was found by the Mariposa Battalion. Mono chiefs once smoked the pipe of peace there with the Ahwaneechees. Major Savage and the men of his battalion spent a night there.

If it is spring, or early summer, look for water-ouzels bobbing along the rocks which border Happy Isles as the Merced River rushes by, flashing white diamonds in the air. In late afternoon drive down to the foot of Bridal Veil Falls to see the ethereal rainbow arching across the water. If it is summer, and the moon is full, climb to the bottom of Yosemite’s upper falls to see the lunar rainbow. Then, if you can turn your back on this moon enchantment, look down upon the Valley where the twinkling lights flicker in the trees below like myriad fireflies. Along the banks of the Merced River, near Pohono Bridge, the dogwood is loveliest in the spring and brilliant again in October. In June azaleas bloom in El Capitan meadows, filling the air with their fragrance. On a moonlit winter night, Lamon’s apple orchard, white with snow, is a vision you will never forget.

It is fun to prowl among the camp grounds in the evening, stopping now and then at some friendly fireside, to exchange data with the campers. You will learn that the roads are good, and the roads are bad. Fishin’ is fine, or there’s no fishin’ at all! Bears at the feeding ground are one thing, bears feeding in your own camp are another.

There are nice, flat rocks near the foot of Yosemite Falls where you can lie and listen to the water as you watch the stars in their courses. There is the Lost Arrow trail, where you can wander in the freshness of the early morning, cooking bacon, if you have permission, in the rocky stream-bed. And there is the museum, chock-full of treasures, where you can identify that strange bird or flower which puzzled you along the trail. Every morning and every afternoon there is an auto caravan tour of the Valley which you make in your own car with the aid of a guide who explains the interesting features of Yosemite.

Then there are the trails! The long ones and the short ones. The steep ones, and the steeper ones. The most traveled from the floor of the Valley are those to Vernal and Nevada Falls, the Four-Mile trail to Glacier, and the Ledge trail. Fewer seem to know about the Sierra Point trail, which is a fairly steep scramble, but a most rewarding one. It branches off from the Vernal Falls trail just above Happy Isles and spirals upward for three-quarters of a mile to a rocky promontory opposite Illilouette Falls, with Vernal and Nevada tumbling to the left of you, Yosemite plunging to the right. You are suspended, as it were, between heaven and earth, looking down upon the Valley, looking up to the Sierra peaks. For a short hike it is one of the most comprehensive and satisfying of all.

Another easy half-day jaunt is up Tenaya Canyon to the Cascades. There is little climbing on this trail as it follows the river closely and is well shaded all the way. It begins at Mirror Lake and meanders through the canyon for several wooded miles.

“If you had only one day in Yosemite what would you do?”

I heard a tourist ask a Ranger this question, and he shook his head sadly and answered, “Madam, I’d weep!”

But if I had only one day in Yosemite, I think I would drive to Glacier Point twenty-eight miles over an oiled highway, taking about an hour and a half each way. There I would climb to Sentinel Dome, a short ten minutes’ drive from the main road. And under that curiously wind-blown Jeffrey Pine, hundreds of years old, I would settle down for one hour’s contemplation of the roof of the world. For nowhere will you find such an unsurpassed view of the High Sierras. “Cycle upon cycle of Sierra peaks, lonely looking, though so many.” Rolling ridges of stone, stretching off into illimitable space. Some are snow-crowned, some are cloud-shadowed. Battalion after battalion they march across the sky, files of pinnacles, domes, and ragged crests. There is lots of room to breathe in up there, lots of time to think. And as you look to the horizon on every side of you, recall those lines—

I inhale great draughts of space,

And the East and the West are mine,

And the North and the South are mine.

And after a while I would wander back to Glacier Point, for the comfort of people, and standing on the top of that sheer cliff which rises straight from the floor of the Valley to the soles of my shoes, almost a mile above it, I would look down into that canyon carved by the silver trickle of water, spilling now over Vernal and Nevada Falls, and marvel that human beings could matter in a universe planned on such a scale.

From Glacier Point I would back-track a little on my way to the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees. I would plan to arrive there late in the afternoon when the shadows were long enough to cast “sun-dogs,” or streamers of light through the trees, and I would walk quietly among them till sundown, as you would walk in the presence of Patriarchs. I would not bother about their size or their age or their cubic contents. I would simply enjoy their peace and their beauty. And after supper on the terrace made from mosaics of Sequoia, I would listen to the wind stir in their needles, so high above, and watch their silhouettes appear against the starlight or moonlight before returning to the Valley in time to see the firefall from the very point at Glacier on which I had stood that morning. And that would be a day of days.

If you have two days in Yosemite you could plan a trip to the Big Trees in the morning and go on to Glacier Point to spend the night. You could have a sunset then from Sentinel Dome or Glacier Point, when the whole world is bathed in color, and in the evening you could participate in that ceremony of shoving the firefall over the cliff, and hearing the embers tinkle as they dropped. In the morning you could return to the Valley either by way of Vernal and Nevada

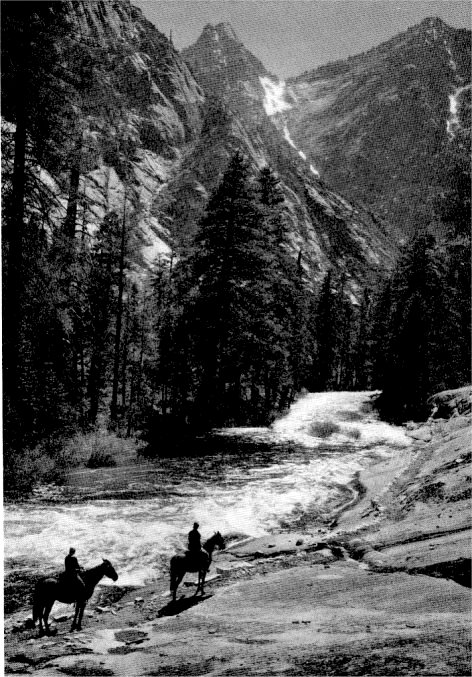

[click to enlarge] |

|

In the Tuolumne Canyon through fir

forests, beside rushing waters, trails lead from one High Sierra camp to another |

You cannot sit and watch Yosemite Falls booming over the cliffs without feeling the urge to climb to the top and peer behind the scenes. Particularly if you have seen the canyon of Yosemite Creek from the Pohono trail, tracing the river from the falls back to where it was born on Mount Hoffman. So if you have a third day in Yosemite, don’t miss that experience. There is no way of describing the sensation you have as you stand beside that deafening roar of falling water where it slips over the brink of the precipice. It terrifies and exhilarates. And there is no better way to gauge the height of the cliffs than to climb up or down that trail in the shadow of those towering walls. From the top of Yosemite Falls it is about a mile to Yosemite Point, a rise which gives a more extended view of the Valley. A supper on Yosemite Point, when the shadows descend on the Valley engulfing it bit by bit, then a hike down the trail in the moonlight is an adventure you’ll boast of for many long years to come.

From the top of Yosemite Falls a trail leads to the summit of Eagle Peak, highest of the Three Brothers, through forests, like those of the Pohono trail, through gardens of wild roses, evening primroses, lupins, shooting-stars, Mariposa lilies, larkspur, and penstamons.

Half Dome is a challenge to both seasoned and tenderfoot hikers alike. Its very bulk and its polished dome seem to defy them. So, to assert man’s superiority, they feel compelled to scale it, even as George Anderson did, back in 1875, when he so laboriously cut steps in the granite to insert the iron pegs by which he eventually hauled himself by means of a rope ladder to its untrodden top. Since then, the egg-shells of thousands of picnickers have blown down its crevices, and still it stands beckoning. On the top of its rounded dome there are about eight acres of flat surface. A few scrubby tree bushes have found root-hold and here and there a tiny alpine lichen relieves the starkness of its barren dome. It is eight miles to the top of Half Dome, and eight miles down again!

Supposing, though, you did not have to count your days by twos or threes. Then what a bit of traveling you could do! You could roll up a map, and a bit of moleskin for blistered heels, and start off on a tour of the High Sierra Camps. You could hike it or ride it, with or without companions, allowing six days, or sixty, according to your blessings.

There are five of these High Sierra Camps, established just a comfortable day’s jaunt apart, approximately ten miles, where simple but highly appreciated food and shelter are provided for a dollar a meal, a dollar a night. And when you have completed a tour of those camps, from Yosemite Valley to Lake Merced, Vogelsang Pass to Tuolumne Meadows, Glen Aulin to Tenaya Lake, and from Tenaya Lake back to the Valley, you have had one of the finest vacations that money can buy. At the top of every mountain pass you have somehow dropped a worry. Fresh winds from the four corners of the earth have blown the cobwebs from your mind. You have burned your nose and hardened your body. You have seen the glories of a mountain morning, heard the music of wind and water, smelled the fragrance of pine forests. In short, you have been places and seen things.

Merced Lake Camp lies in a high, wooded valley on the shores of a beautiful lake, where the fishing is excellent. Because of its ideal location, and its proximity to other fishing streams, it is one of the favorite High Sierra Camps.

Vogelsang Camp is the highest of all, perched on the top of a pass at an altitude of 10,000 feet above sea-level. It lies above timberline, stark and impressive in its austere beauty, up where the winds and the clouds are born. Above the camp and one mile to the east lies Bernice Lake, cradled in an amphitheater of rock, and several hundred feet above is a chain of lakes where the trout flash temptingly.

Tuolumne Meadows is known to all lovers of the Sierras. It is the hub of the High Sierras, a sort of Grand Concourse from which many trails radiate. Like the Grand Central Station in New York, if you stay there long enough you will encounter all of your trailside buddies. Surrounded by such imposing peaks as Dana, Mount Conness, Lyell, Cathedral, Echo, and McClure, crossed by the mighty Tuolumne River, twin to the Merced, the Meadows attracts thousands of fishermen, mountain climbers, campers, and hikers each year. As in Yosemite Valley, there in the heart of the Sierras you will find that combination of almost forbidding grandeur and ethereal beauty; noble ranges and fantastically shaped peaks, granite knobs, polished to shining glory, rising out of wild-flower meadows and sylvan groves. And through it all races the Tuolumne River, “one of the most songful rivers in the world,” as John Muir declares.

Glen Aulin is beautifully located beside the White Cascade Fall on the Tuolumne River. It is one of the newer camps to be established, opening to new worshipers each season miles of that tumultuous canyon where the Waterwheel Falls leap in the air. Fishing is extraordinarily good in this region, and the aspens, in the late season, are a sight for your soul.

From Glen Aulin it is only a little over seven miles to Lake Tenaya, “Lake of the Shining Rocks,” as the Indians named it. Wooded on one side, with a tree-fringed shore on the other, and glacial domes rising from its waters to brush the skies, this is one of those ideal pictures with which vacation pamphlets lure you. Here the last of Tenaya’s tribe were surrounded and captured by government soldiers. The waters of this lake seem particularly blue, perhaps because of the glacial dust. For as dust makes the sunsets by light reflection and refraction, so does finely powdered rock in the mountain lakes account in part for their intense blues and greens. The trip from Glen Aulin to Tenaya Lake passes not far from May Lake, at the base of Mount Hoffman, where a winter camp for ski enthusiasts is being planned.

From Tenaya Lake you return to the Valley by way of Tenaya Canyon and the zigzags. But if you can manage to commandeer a ride down the Tioga road, for a few miles, to the junction of the Yosemite Falls trail, you will have a glorious hike along Yosemite Creek, through magnificent forests, to the top of Yosemite Falls, then down into the Valley. That is as grand a finale for such a tour as the most exacting could ask.

When you have toured the High Sierra Camps, however, you have only made a bowing acquaintance with the Park. For there is just as much more in comparison to what you have seen, as you have now seen in comparison to those who never left the floor of the Valley. Over every ridge you passed lies another ridge. Beyond every lake and stream gleams another. There is Pate Valley and Hetch-Hetchy, Benson Lake and the Devil’s Post Pile. There is the Isberg Pass and the Forsythe trail, the Sunrise trail and Thousand Island Lake. There is Cold Canyon trail and Babcock Lake trail, and trails too numerous to mention. And there is Shadow Lake and Shadow Creek, Ten-Mile Meadows and Jackass Mountain, Piute Creek and Matterhorn Canyon. Names to conjure with, places to explore!

But once you get the bacilli in your blood stream rest assured you will be back. For there is no cure for mountain-itis except mountains; no allaying that trail-fever except by trail-trekking. And of all the treatments under the sun and the stars, there is none easier to take than that of traveling the trails of Yosemite!

Next: Indian Legends • Contents • Previous: Trees of Yosemite

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_tales_and_trails/trails.html