[click to enlarge]

shadow of giant Sequoias which

were old when this nation was born

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Tales & Trails > 5. Big and Little Trees of Yosemite >

Next: Traveling the Trails • Contents • Previous: Making a National Park

EVER so often do you feel a hankering for trees, a fever for the sight and the sound and the smell of them? Do cities crowd upon you, elevators and office buildings, asphalt and cement, until it seems as if you had to escape to some forest where the pine-needles are spongy underfoot and the wind soft overhead?

When you feel the first symptom of this tree-itis breaking out in you it is time to be off to the Sierras. For Horace Greeley once said, “They surpass any mountains I ever saw in wealth and grace of trees. Look down from almost any of their peaks and your range of vision is filled, bounded, satisfied by what might be termed a tempest-tossed sea of evergreens, filling every upland valley, covering every hillside, crowning every peak but the highest with their unfading luxuriance. I have never enjoyed such a tree feast before.”

Man’s interest in trees is an old one. It goes back to that day in the Garden of Eden when Adam and Eve ate of the Tree of Knowledge. According to Darwin, it goes back even farther! But from whatever it springs, in Yosemite you can satisfy that tree hunger completely, for you will find there nearly every species of tree which grows in the Sierras, from the stunted, tortured growths at timberline to the Giant Sequoias in the canyons.

Those trees at timberline tell a tremendous story. Beaten by gales, burned by the sun, bowed beneath blankets of snow, they are the hardy survivors who have fought their way to the very summit of the Sierras, to that last frontier beyond which even the most venturesome dare not go. Up there, near timberline, you will find species of the scrub pine, spruce, fir, aspen, birch, willow, and juniper. Gaunt, gnarled, and grotesque, those doughty old warriors command as much admiration and respect as the giants which tower in the valleys below. Clinging precariously to rocky ridges they have held their own for hundreds of years in the face of overwhelming odds.

Many of those gnomes at timberline are as old as the majestic yellow and sugar pines which grow in more sheltered places. Enos Mills examined one dwarf pine,

[click to enlarge] |

|

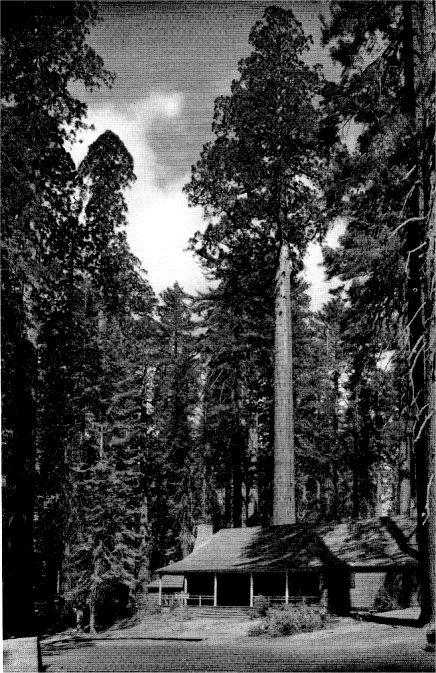

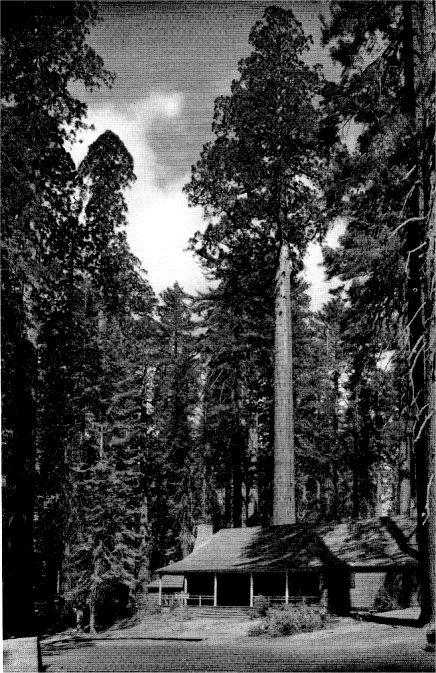

The Big Tines Lodge lies in the

shadow of giant Sequoias which were old when this nation was born |

Many of those trees up there, like human beings, look older than they are because of the storms they have weathered. But the juniper tree, most spectacular of all, has been known to live a thousand and even two thousand years. Sturdy and storm-enduring it clings to rocky domes and ridges seven to ten thousand feet above sea-level. It is a solitary and individual tree, never grows in forests and seldom in groves. When killed, the juniper is said to waste away about as slowly as granite. In early days it was believed that the shadow it cast was harmful to human beings, yet its berries were a panacea for all ills. That belief must survive, for today they are used chiefly for the flavoring of gin! The wood of the juniper was a symbol of faith, for its heart was always sound, and its branches were often burned on funeral pyres. Indians used the tough, stringy bark to weave matting and coarse cloth. A useful and historic tree, the juniper.

From this outpost of pines, silver firs, hemlock, humpbacked juniper, and tamarack, the trees straggle down from the timberline, becoming larger and more imposing as they go. In the more temperate, middle regions of the Sierras, the real monarchs of the forest are found, the sugar pine, the yellow pine, the Douglas fir, live oaks, bays, cottonwood, aspens, dogwood, maples, cedars, and king of all trees, the Sequoia Gigantea.

The yellow pine, “clad in thick bark like a warrior in mail,” is a nomad among trees, for it is found anywhere from British Columbia to the Mexican border, from the Pacific Ocean to the Black Hills of Dakota. Like the true traveler it is, it accommodates itself to granite slopes, lush valley bottoms, hot sands, and dry highlands. It is a grand old tree with bark like an alligator’s skin, which peels off in small segments, or scales, like pieces of a jig-saw puzzle. One of the finest specimens of yellow pine stands not far from Sentinel Rock in Yosemite Valley. It is more than five hundred years old and was standing there long before Columbus was born, and will probably continue to watch over Yosemite destinies for centuries to come. The trunk of this tree is twenty-five feet around, and its branches form a canopy one hundred and three feet across. Yet it is doubtful if one out of twenty visitors to Yosemite even knows of its existence.

The yellow pine has a rival in popularity in the sugar pine, which is generally conceded to be the largest and noblest of the seventy or eighty species of pine trees in the world. That puts it, in majesty, second only to the Sequoia. Curiously enough the flowers of this mighty tree are no larger than those on the puny dwarf pines at timberline, and far less showy. So Nature distributes her favors! John Muir has said that a pine forest in bloom is a rare treat, but one few people ever enjoy because when the tree blooms the high mountain passes are still choked with snow.

The Douglas spruce is a relative of the well-known Norway spruce, which, because of its long, straight shaft, has been used so long in making masts. From the depths of distant forests the trunks of these trees have gone out to sail the seven seas. Our term “spruce-looking” may well have come from this trim, neat shaft.

The incense cedar is interesting not only because it grows to a venerable old age, but because of a peculiarity it has of blooming months ahead of its fellow trees. Late in the autumn, or in early winter, it puts out masses of yellow blossoms which often poke up through snow on its branches, and is said to resemble a golden-rod against a snowy background.

The oak trees of the Sierras were the pantry shelves of the Indians. They depended a lot upon the harvest of acorns to get them through the winter and it was a good or a bad season according to the yield of acorns. They formed one of the chief products of barter and trade with the other tribes, and because of the number of oak trees in Ahwahnee the Yosemite Indians had a corner on this commodity. The two most common species of oak are the white, or live, oak and the black, or deciduous, oak, which drops its leaves in the fall after turning yellow, rust, and orange to add to the glory of fall.

The quaking aspen is another of the triumphs of a fall in the Sierras, or the Rockies, or wherever you may find them. Its leaves turn the yellow of gold and flaunt their colors like gay scarfs draped over the mountain’s shoulder, trailing through shadowy forests, reflecting themselves again in the streams and lakes. According to the Highlanders of Scotland the cross on which Christ was crucified was made of aspen, and a curse was laid upon the tree, causing its leaves to tremble until they dropped from the branches. Whether quaking in terror or trembling with joy, the aspen’s leaves are always astir, twinkling, murmuring, rustling, even on the stillest day. And whatever the cause of their movement there is an excitement about their fluttering which lifts the spirit a bit and always attracts more attention to them than to the more dignified companions standing staid and erect beside them.

Mary Austin claims that all the trees of the Sierras have a voice of their own. Each has a characteristic note, she says, by which a traveler in the dark of a mountain night can learn to know his way among them as other men do by the street noises of their own city. There is the creaking of the firs, the sough of the long-leaved pines, the whispering whistle of the lodge-pole pine, and the delicate frou-frou of the redwoods in the wind, each as different as the voice of a companion once you have learned to distinguish between them.

In the deep peace of the solemn old woods stand the Big Trees, the Sequoias Gigantea, just as they have stood from time immemorial, defying the storms of thousands of years, impervious to the rise and fall of ant-like nations, living, growing, blossoming and germinating again, century upon century. They are the ancients of the world, ageless, raceless, for all time and all peoples. Mary Curry Tresidder, in her “Trees of Yosemite,” says of these oldest living things: “They were seedlings when Alexander sighed for more worlds to conquer, had become mere saplings when Christ was born, and had attained the grandeur of their prime long before Columbus set eyes upon this continent. It is not merely an ordinary tree raised to the nth power, but is the apotheosis of a tree.”

And still they stand, high priests of the Sierras, that we of the twentieth

At one time the genus of this tree spread over three continents, Europe, Asia, and North America, but all have perished now except those two species found in California, the Sequoia Gigantea and the Sequoia Sempervirens, or Coast Redwood.

There are three groves of Big Trees in Yosemite Park—the Mariposa Grove, the largest and best known, containing something over two hundred giants; the Tuolumne Grove, on the Big Oak Flat road, with twenty-five of the larger trees; and the Merced Grove, near Hazel Green, with twenty or more.

There have been many controversies over the age of the Big Trees and a conservative estimate seems to be that the oldest have lived between three and five thousand years, with unlimited life ahead. It is certain, according to Colonel White, of Sequoia National Park, that they live four thousand years, reasonably certain that they can live five thousand or six thousand years, probable that they may live seven thousand or eight thousand years, and not improbable that they may live ten thousand years if protected. At any rate they are older now than any other living thing on earth, having long outlived the dinosaurs and the ichthyosaurs of their youth, and appear to be as vigorous now as they were in their first thousand of years.

It is amazing to think that a tree the size of the Grizzly Giant, largest of Yosemite trees, sprang from a seed no larger than a spinach seed. From that infinitesimal germ grew a tree which measures ninety-four feet at the base of its trunk and stands two hundred feet high. The General Sherman tree in Sequoia National Park is 102 feet at its base and towers 273 feet towards the sky. Such a tiny seed, as Colonel White and Judge Fry point out in their book “Big Trees,” can produce a tree which contains enough lumber to build a village of one hundred and fifty houses of five rooms each!

One of the great beauties of the Big Tree is its deeply fluted, reddish brown trunk which rises so straight and free of encumbering branches to a height of a hundred feet or more. As the tree ages it drops its lower branches and those remaining often become as large around as the trunk of an ordinary tree. The bark which protects the heart of these monarchs is often a foot and a half in thickness. As it is the outer and most important defense of the tree it was especially designed by Nature to resist fire, insects, and disease. For all its thickness it is spongy and almost as light and resistant to fire as asbestos because it contains so little resin. It is filled, too, with a dust which has a high percentage of tannin in it. This discourages the inroads of insects and helps to insulate the tree against extremes of heat and cold.

The Big Tree is certainly an outstanding example of the survival of the fittest. For of the millions of seeds each tree sows every year only a very few germinate. And of these few still fewer survive the ravages of birds, cutworms, wood-ants, rodents, and forest fires. Literally the first hundred years are the hardest with the Sequoias!

Lofty and aloof these trees stand in dignified stateliness. No fantastic, wind-blown contours here, or picturesquely gnarled branches. Their great trunks rise like fluted columns, and though the crowns of most of the oldest have been damaged by fire they maintain a majesty which makes them one of the wonders of the world. There lives a world beneath them and a world above. Deer and bear and a kingdom of smaller, scuttling animals live and die at their feet, while above their heads birds soar and sing, and die; clouds gather, storms rage, still the Sequoia stands calm and mysterious, in a green eternity, with its head in the clouds and its roots deep, deep in the soil, a link between heaven and earth.

And as you wander through the aisles of the Big Tree forests you understand why the ancient priests and philosophers chose the groves for their first temples, planting trees in a circle to make their amphitheaters. While Pliny and his followers were meditating in some distant woods the Big Trees were already growing on the slopes of the Sierras, gathering their peace and quiet and strength to share with all who walk beneath them.

Next: Traveling the Trails • Contents • Previous: Making a National Park

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_tales_and_trails/trees.html