[click to enlarge]

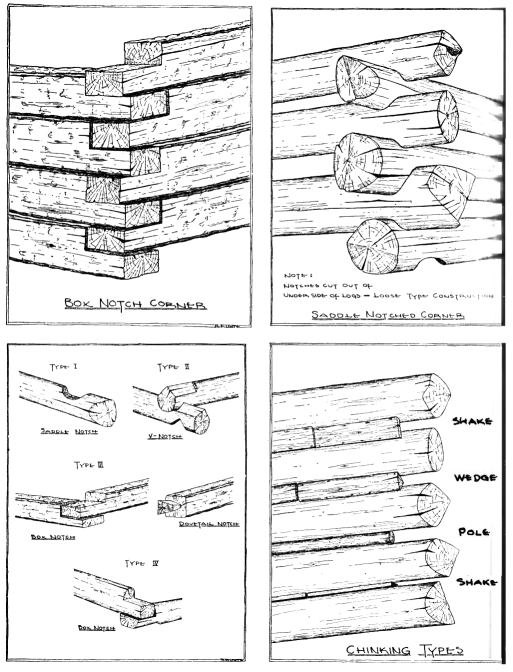

Notching and chinking types

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Pioneer Cabins >

Physical evidence of the many cabins built by pioneers in the Yosemite region is disappearing so rapidly that persons interested in the history of the region have felt it worthwhile that such material as is available be gathered together quickly. The project of digesting and presenting data on the subject was assigned to me as an official duty in the course of my work as a park ranger in Yosemite National Park. The sources available to me were the field notes and rough sketches and photographs graphs made by the several park rangers who investigated the old structures during the summers of 1949 and 1950. The account here does not pretend to be complete, and it may not be possible ever to obtain the full story of some of the cabins—even of some of those which are still standing; there may be no survivors to relate the details. It is hoped that some further information will be brought to light by readers of the present article.

As a bit of background, we know that log-cabin construction was common in the Delaware River Valley as early as 1640, and credit for the basic design has generally been given to the pioneer Swedes and Finns. Later, logs were used to construct forts and prisons in the English colonial settlements. In Pennsylvania the Germans used logs for “temporary” homes, many of which stand today. Log cabins housed the first schools and churches in many parts of the West, and helped to house the first seat of government of the Republic of Texas and elsewhere on the frontier. The construction of the cabins themselves reveals some of the culture of the early settler—his personality, character, experience, his national antecedents, and his ability to cope with the situations which confronted him. In general, the old cabins of the Yosemite region are not architectural gems; most of them are simple, even crude, but they reflect some of the hard-bitten qualities of their builders and they are worthy of attention from those who would know more of the history of the pioneers in the Sierra. In seems appropriate to review this history now while we are observing the 100th Anniversary of the effective discovery of Yosemite.

Present-day cabin builders find it next to impossible to equal the better structures of the pioneers, owing chiefly to the growing scarcity of good materials and of inexpensive but painstaking labor. Nowadays builders in many parts of the country are content to sacrifice true logs for a log veneer on the exteriors, and to compensate by making the interiors more

[click to enlarge] Notching and chinking types |

Two basic types of construction are represented in the Yosemite cabins —they are built of hand-hewn logs which are round in one type, square in the other. The methods of corner joining are more varied, however, and it is by these variations that I have classified the cabins, also taking into account the character of the logs themselves, as well as the methods of chinking. Most of the Yosemite cabins investigated were built with round logs and saddle notching at the corners. This type of construction was easy and rapid, for if the saddle notches were not cut deep enough for a tight fit, then larger chinking could be used. The cut I have called a V-notch, for lack of a better name, was also sometimes used with round logs, and was probably easier to make than the saddle notch, a V being easier to cut than a U. Although we may speculate which was better, the saddle notch at least produced a more finished appearance. A more difficult but better method of corner joining was the dovetail or box corner, customarily used with hand-hewn logs but occasionally found on round logs. Dovetailing made for a tighter fit, and chinking could often be dispensed with. When necessary, various methods of chinking were used—split shakes laid flat or on edge between the logs; small poles cut to fit snugly into the crevices; wedge-shaped slabs laid between the logs, or a complete covering of split shakes, laid vertically against the side walls as on a roof. This latter type of construction was quite common in the Yosemite region because of the ready availability of sugar pine from which the shakes could be made right at the cabin site.

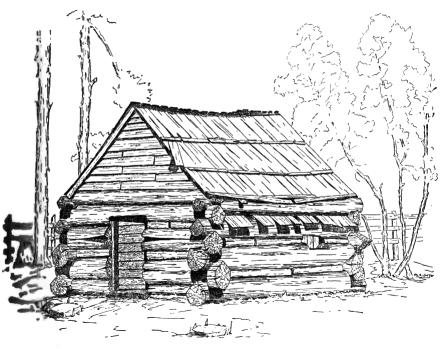

Biledo Meadows.—Southwest of Mount Raymond near the enormous springs of Biledo Meadows just outside of the park are two unusually handsome cabins, one of hand-hewn square logs, the other of round timbers. The latter was built in 1890 by Thomas Biledo,* a French-Canadian miner who came to the vicinity in the ‘eighties and was employed by the Mount Raymond Mining Company. The logs are eight-ten inches in diameter and laid on a loose rock foundation. The cabin is sixteen by fourteen feet in area, with an overall height of sixteen feet. It is chinked with hand-split shakes laid parallel to the logs; the gable is filled in with vertical boards. A new roof and superstructure were added by the present owner in about 1932. The cabin was originally built with meticulous care and is in excellent condition. It finds regular use each summer and fall and, evidently, will last for many years.

[*The name should be spelled “Biledeaux” according to John Wegner (assistant chief ranger, 1916-1944), who knew the builder.]

Crane Flat.—Three log structures were erected by the National Park Service in 1915 as guard stations—the Crane Flat cabin, which still stands, although altered in recent years; another, now gone, in the Merced Grove of Big Trees; and the Hog Ranch cabin, which was replaced by the present Mather Ranger Station in 1935. The Crane Flat structure is the most spacious one studied. It originally had an enclosed floor space of 850

[click to enlarge] Biledo cabin (type I) |

Cunningham.—Stephen Cunningham, born and educated in England, assisted Galen Clark as keeper of the Big Trees; on the flat below Camp A. E. Wood, Wawona, and approximately eighty-five yards from the South Fork of the Merced River he built his log cabin and lived for many years. The flat which now bears his name is under development at this moment by the National Park Service as a modern campground. Cunningham filed on this land in 1861, but it is not known when he built the cabin. The structure has disintegrated to the point of complete ruin. It was eighteen by twenty-one feet, fronted on the river, and was quite luxurious compared to many of its contemporaries. All that remains of the fireplace and chimney is a pile of angular pieces of granite; no mortar was used. The walls, built of eight- to twelve-inch yellow-pine logs were neatly saddle-notched; in spite of the general ruinous condition many of the logs still fit together snugly. There is no evidence of chinking; the shakes found in the ruins were probably from the roof.

Cunningham supplemented his income as an employee of the Yosemite Grant by making curios which he sold to visitors in the Mariposa Grove. He had his own wood lathe and devoted his spare time to turning out souvenirs. A carriage road from Clark’s Station (Wawona) gave access to his cabin and it persisted as a dim trail through the forest until recently when it was obliterated by the construction of a modern road into the new Cunningham Flat Campground.

Hodgdon.—At the southeast end of the Aspen Valley meadow is the Jerry Hodgdon cabin, the only two-story log cabin in or near the park. Several additions to this structure were made in later years—a front porch, a lean-to kitchen on the west side, and an outside stairway on the south end. The overall size is twenty-two by fourteen feet. A shake roof covers the perlins, which are parallel to the sides and extend about two feet on each end of the cabin. The base log suffices for a foundation. The building timbers, carefully notched on both upper and lower sides, give a neat appearance. The wedge-shaped chinking is barely distinguishable at a distance.

Hodgdon began work on this cabin in 1879, and was assisted by an old Chinese called Babcock (see below). The cabin was built for living quarters on the Hodgdon homestead and was occupied as such until a still larger home was constructed. The cabin was later used for summer billeting by a detachment of cavalry soldiers. Descendants of the Hodgdons still own and reside upon the Aspen Valley property.

East Meadows Cache.—The small trapper’s shelter in the East Meadow portion of the Hodgdon Estate near Aspen Valley has rotted almost to the ground, but its features are still distinguishable. It was only eight feet long and six feet high. It had no windows and was entered by means of a trap door in the roof. The cabin housed a very small stone fireplace and chimney.

This shelter was built by a Chinese called Babcock, an employee of Jerry Hodgdon, and used as a cache on Babcock’s trap line. It is the only structure of this type known to be in the park.

Lembert.—John B. Lembert took up a homestead at Soda Springs, in Tuolumne Meadows, in 1885 and occupied himself at his high mountain summer quarters raising angora goats and collecting plant and insect specimens from surrounding meadows for museums all over the country. Lembert was living at Soda Springs at the time Prof. George Davidson was doing triangulation work in his temporary observatory on Mount Conness. Davidson reimbursed Lembert for the use of his property as a base camp and pasturage.

Lembert built his crude, one-room cabin of large round timbers laid on a granite stone foundation. The logs were chinked in a rather random manner with shakes, which were also used for the roof. Crude though this cabin was, it was adequate for summer occupancy. Lembert spent his winters in his cabin at the Indian Village, just below El Portal.

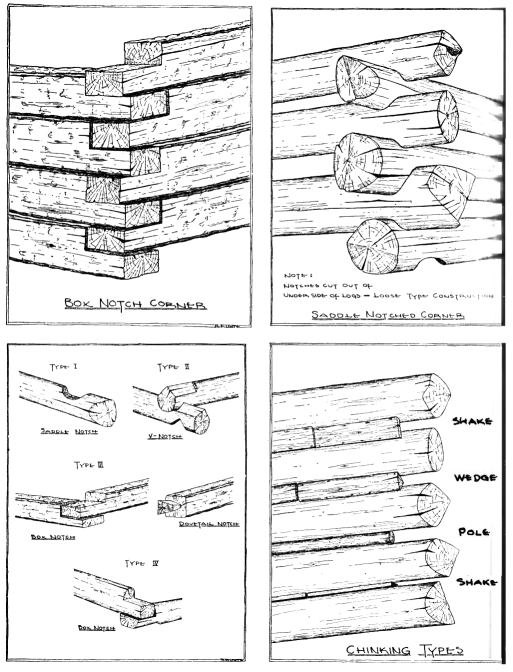

Mariposa Grove.—Galen Clark built his first log hut in the Mariposa Grove in 1858, a year after his discovery of the grove. Two photos taken about this time purport to be of the original cabin, but the differences in the photographed structures indicate that there were two different cabins on the same site. The two cabins are of the same size and in the same place, but the earlier one had shake chinking and an uncovered triangular stockade at one end, which possibly was used as a kitchen. There was no covering over the triangular area so a chimney was unnecessary.

According to the Yosemite Valley Commissioners’ Biennial Report, 1885-1886, still another one-room log cabin was constructed in the grove, “for the shelter and convenience of visitors.” Several years later, it was lengthened by the addition of another room. This structure, generally known as the “Galen Clark Cabin,” stood for the next forty-five years, and its fame spread throughout the world, largely through the agency of photographs depicting it and its astonishing setting. In 1930 the Park Service replaced it, for owing to decay its collapse seemed imminent.

The new cabin stands on the original site, and while not an exact duplication of its predecessor, resembles it enough to carry on the tradition. We can fancy it is just the sort of log cabin Galen Clark would have built had building conditions been as favorable in his day. It differs structurally from the cabin it replaced, but not in general design. Every measure has been taken to insure it long life. It has a rubble masonry foundation and a reinforced chimney. It is constructed of carefully fitted sugar-pine logs tied with steel dowel-pins and chinked with split-log strips over oakum packing. The shake roof is laid on roofing paper and solid sheathing. It has doweled, random-width oak flooring. The cabin now houses a small museum exhibit devoted to the sequoias.

[click to enlarge] Galen Clark’s first cabin—Mariposa Grove Replaced in 1885–86; second cabin rebuilt in 1930 |

McGurk Meadows.—In McGurk Meadows, one mile west of Bridalveil Creek and about one mile north of the Glacier Point road, is the site of a stockman’s cabin similar in appearance and construction to the cabin in Mono Meadows. Lodgepole logs, notched on the under side only and about ten to twelve inches in diameter, were used to a height of four and a half feet for the walls, the base log being laid on the soil. Fireplace, windows, and flooring have been omitted. Wedge-shaped chinking filled the wide gap between logs. The doorway is four feet high. Shakes were used to cover the roof, which measured nine feet from eave to ridge.

This cabin was intended to have been part of the homestead of John J. McGurk, but through an error in description, the wrong property was filed upon. Thomas M. Again originally filed for the 160 acres intending to claim what is now known as McGurk Meadows, but the description entered into the county records placed the claim well up Illilouette Creek. Hugh Davanay subsequently acquired this mistaken title from Again, and sold to McGurk in 1895, who continued in possession until August 1897, when he was removed by U.S. troops, then the custodians of the national park. Their basis for this removal was the error in the original description of the claim patented by Again; the patent was for an area six miles directly east of his intended homestead. After his removal, McGurk forced Davanay to reimburse him for his loss and Davanay in turn tried to effect a trade with the General Land Office for the desired piece of land, but was refused. The land covered by the original patent was exceedingly rough and was considered worthless; Again could not dispose of it. Thus, McGurk

[click to enlarge] McGurk cabin |

Mono Meadows.—The Mono Meadows cabin is on the Mono Meadows trail about one mile east of the Glacier Point road. It is built of small lodgepole pine logs with no indication of chinking. There is no foundation, window, or floor. The doorway faces north, and is four feet high and three feet wide. The overall size of the cabin is fourteen by fourteen feet. The walls are doorway height and the gable extends to nine feet.

This construction is like that of the McGurk cabin except that the logs used average only six inches in diameter. This shelter was built by Milt Egan and used seasonally as what is generally known as a “summer line cabin.” Its later use was probably restricted to shelter for a sheepherder or cowboy when the adjacent meadow was grazed. The cabin is in a poor state of repair and is useless at the present time.

Murphy.—The west shore of Lake Tenaya is the site of a one-time long rectangular structure built by J. L. Murphy on the Tioga Road as a home and a hospice for wayfarers. Murphy’s roadhouse actually antedated the building of the road. Murphy occupied it only during the summer season, at which time he employed a cook and catered to travelers and campers. In winter he lived in Mariposa.

A photo of this cabin taken about 1890 shows a group of travelers, one of them being Galen Clark. This cabin has long since perished, but from this old photograph one is able to ascertain most of its physical appearances, and discover the substantial manner in which it was constructed. About one-third of it—that which housed the dry masonry rock fireplace and chimney—was built of exposed logs and chinked with large boards laid horizontally. Evidently this was Murphy’s basic cabin. The other two-thirds appears to have been a later addition and differs greatly in that it is a frame structure completely covered by split shakes laid horizontally. The entire cabin is covered by a roof of split shakes which overlap on one side of the roof ridgepole, thereby sealing the roof from rain and snow.

An excellent description of this shelter and its surrounding terrain is found in an excerpt from the Daily Free Press of Bodie dated August 18, 1882: “The ample meadows surrounding Lake Tenaya at its eastern and western extremity are now owned by J. L. Murphy, who settled there and fenced in the property years ago. This gentleman also stocked the lake some years ago with trout, which are now quite abundant in its waters. On the northern shore, at a point about half way between the two ends, he has built a comfortable log house for the accommodation of guests, all the board work for which, roofing, etc., has been turned out by the laborious process of whipsawing.”

Snow Flat.—The remains of the Snow Flat cabins can be found along the trail that leads to May Lake, about a hundred yards off the Tioga Road. No actual history is known of these cabins, and they have deteriorated to the point where one can only deduce what they looked like. The only trace of one of them is a pile of large granite boulders, presumably a dry masonry fireplace and chimney. The other cabin, a short distance away, has been reduced to a small square enclosure four logs high which look like a corral. The cabin was built of rough round logs laid on a stone foundation—a large boulder placed at each of the four corners. The logs were saddle-notched above and below and were closely joined at the corners. Wedge-shaped chinking was used. Piles of ore samples are to be found around the cabin sites.

Beehive.—The two Beehive cabins, seven miles north of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir on the Jack Main Trail, were both built by the same family but are of different construction types. One was built on a loose rock foundation and had five horizontal logs on one side and six on the other. Short stumps or uprights were placed between the logs at various intervals to keep them from sagging—an expedient used in no other Yosemite cabin. The overall size is fifteen by twenty-four feet. Shakes covered both roof and sides. The cabin had no flooring; the occupants slept on bear rugs, believing this to be warmer. The roof has disintegrated.

This cabin was built in 1888 by Lewis and Eugene Elwell, early settlers and cattlemen in this area.

Crescent Meadows.—The Cresent Meadow cabin near Wawona was built of lodgepole logs about nine inches in diameter, joined by a V notch, the four-inch clearance between logs being chinked with wedge-shaped strips and split shakes laid flat to cover the crevices. Several large rocks were placed beneath the base logs to serve as a foundation. The fireplace and chimney, which have collapsed, were of a dry masonry type.

According to Bob McGregor, a government packer, the cabin was built by Robert Wellman for the livestock partnership of Stockton and Buffman. Some residents of Wawona believe it was built about 1887 and contemporary photographs sustain this idea.

Dana Fork.—An old sheep-camp cabin is situated on the Dana Fork, about a mile and a half from the Tioga Road on the Mono Pass Trail. Two photographs, one taken in 1925 and the other in 1949, show that the structure has deteriorated very slightly during the last twenty-five years. Construction was of white-bark pine logs eight logs high, which make an overall height of not more than seven feet. Deeply cut V notches at the corners allow for a tight-fitting chinking. Four long stringers spanning the length of the structure on each side of the ridgepole give support for the roofing material. This consisted of small poles laid parallel to the end of the building and bound together by split shakes. The shakes have disintegrated. All other features are much the same as those discussed in other cabins of this general construction type. No inkling of the history of the builder has been obtained.

Lamon.—The Lamon cabin is recorded as the first log cabin built in Yosemite Valley. James C. Lamon was one of the mountaineers who aided in the construction of the “Upper Hotel” or “Hutchings House” in 1858. The next year he located a preemption claim at the upper end of the valley and built this small but comfortable log cabin. Lamon used unusually large logs for his home, but they were so skillfully notched on both the upper and lower sides, and joined so proficiently at the corners, that the result was a very tight, compact little shelter. The logs were graduated in size from the base log up to a small gable which was filled in with horizontal split shakes. The perlins were parallel with the sides and were covered with split shakes. These overlapped the ridge on one side, assuring complete drainage for the roof. Numerous pictures of this cabin were published in the early books pertaining to Yosemite.

[click to enlarge] Lamon cabin |

Lamon recorded his claim to 160 acres of land in Yosemite Valley on May 17, 1861.* At the same time that he built his home he planted a fine apple orchard in the valley which still flourishes today. Lamon resided here for fifteen years and endeared himself to his Yosemite neighbors. His death in 1875 marked the passing of one of the most colorful and best known pioneers in early Yosemite affairs.

Mono Pass Miners.—The Mono Pass Miners’ cabins are a series of shelters at the head of Bloody Canyon. They were erected by the mining company which owned the Golden Crown mine to house its employees during a period when it was believed that the summit country would produce riches. Although the cabins were erected in the ‘seventies they have withstood time and the ravages of the elements.

[*“Land Claims” (K) p. 363, Mariposa County Records.]

White-bark pine logs were employed, the first of which rested on the ground, and all corner notching was V-shaped, producing a tight fit. Wedge-shaped chinking was inserted between timbers at both interior and exterior angles, making the cabins doubly protected. The stringers spanning the roof are parallel with the facade, and over these were laid vertically a series of short, small logs, placed tightly together and extending from the center ridgepole to the eaves. Apparently sod from the near-by meadow once covered the log roof.

Tiltill Mountain.—The stockman’s cabin at Tiltill Mountain was built by the Elwell brothers in 1888, the same year they erected the Beehive cabins. It is not known how long the Tiltill Mountain cabin was used, but indications are that it was occupied only seasonally and for the several years that the Elwell cattle grazed in that area.

Two large trees have fallen over this cabin in recent years, but structural features can still be distinguished. The walls were five logs high, and the corners were V-notched. Chinking of split shakes approximately eight inches wide was used to bridge the interval between logs. The overall dimensions of the shelter were ten by twelve feet. Roofing was of split shakes. The base log rested on the ground. Flooring was of packed earth.

John Muir.—John Muir, “The Father of Yosemite National Park,” came to Yosemite on foot in 1868 and made headquarters in Yosemite Valley for about five years. He obtained employment at Hutchings’ sawmill cutting lumber for the hotels and cottages then being built in the Sentinel group. He boarded with the Hutchings family and occupied a cabin he built for himself near Hutchings winter home along Yosemite Creek. The Muir cabin was a small hideout almost obscured from view by the surrounding trees and shrubbery. Muir used round logs for his home, joining them with a V notch. The perlins were parallel to the ridgepole and extended beyond the cabin two to three feet. A shake roof covered the structure and overlapped the ridgepole on one side.

The shady environment of this cabin was not conducive to rapid melting of the snow on its roof, so Muir compensated for this by constructing a steep-pitched roof which tended to rid itself of the snow when the roof became too heavily burdened. Shakes laid flat covering the crevices between the logs produced adequate chinking for the abode.

Muir used his hands and heart in the construction of his home. A description of the cabin interior in Muir’s own writing* will give the reader the best picture of the quarters. “This cabin, I think, was the handsomest building in the Valley, and most useful and convenient for a mountaineer. From the Yosemite Creek, near where it first gathers its beaten waters at the foot of the fall, I dug a small ditch and brought a stream into the cabin, entering at one end and flowing out the other with just current enough to allow it to sing and warble in low, sweet tones, delightful at night while I lay in bed. The floor was made of rough slabs, nicely joined and embedded in the ground. In the spring the common pteris ferns pushed up between the joints of the slabs, two of which, growing slender like climbing ferns on account of the subdued light, I trained on threads up the sides and over my window in front of my writing desk in an ornamental arch. Dainty little tree frogs occasionally climbed the ferns and made fine music in the night, and common frogs came in with the stream and helped to sing with the Hylas and the warbling, tinkling water.

[* The Life and Letters of John Muir, I, pp. 207-208.]

“My bed was suspended from the rafters and lined with libocedrus plumes, altogether forming a delightful home in the glorious Valley at a cost of only three or four dollars, and I was loath to leave it.”

Hutchings.—James Mason Hutchings is another name that has grown to be almost synonymous with early Yosemite history. In addition to his proprietorship of the Upper Hotel or Hutchings House in the Valley, he publicized Yosemite in his California Magazine and in his several books on the Sierra. His In the Heart of the Sierra, 1886, bears the imprint, “Published at the Old Cabin, Yo Semite Valley.” Hutchings was born in Towcester, Northhamptonshire, England, February 10, 1820. He left England in 1848 and arrived in Yosemite June, 1855. In 1863, he purchased the Upper Hotel from the Hite brothers, George and John, and after acquiring this primitive two-story inn, he laboriously supplied it by pack mules over the narrow rugged fifty-mile trail from Coulterville. At first, the hotel structure was most unrefined, as records indicate when Hutchings first purchased it. The windows, doors and partitions were all of thin muslin, but Hutchings proceeded to make improvements and additions so that it eventually became a reasonably comfortable lodging for the many guests who resided there while visiting the wonders of Yosemite. He used 109 saddle and pack horses to carry guests from the hotel to points of interest in and around the valley, and his fame as a guide was quite as notable as was his reputation as hotel keeper.

Hutchings’ home for his family of wife and three children was erected on the warm side of the valley near Yosemite Falls. James C. Lamon assisted in the building. Round logs were placed on a stone foundation, and joined with a V notch. A covered open porch or lean-to occupied one side of the building. Later, a frame addition was built on the opposite end to supply added living space for the family. The cabin boasted a large stone fireplace and chimney. Two extremely large granite slabs were used to form the mantel and hearthstone. Split shakes were used to roof the cabin and to chink between the logs. This residence was torn down during the early years of Army administration in Yosemite Valley.

Hutchings served as Guardian of Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove from 1880 to 1883. Florence, one of two daughters born to the Hutchings, was the first white child born in Yosemite; she died there at the age of 18 and Gertrude, the other daughter, affectionately known today as “Cosie” by the local Yosemite inhabitants, came back to the park in the 1940’s after many years of absence and resided there until 1949.

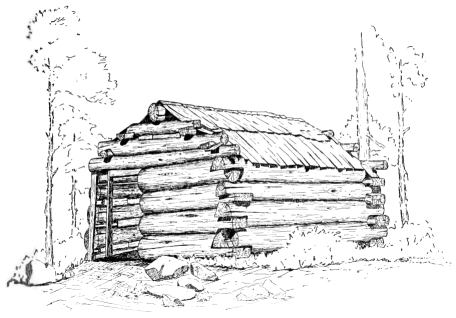

Biledo Meadows.—A compact hand-hewn log cabin is the second of two cabins on the Thomas Biledo claim on the southern boundary of the park near the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees. The builder is unknown, but available information indicates it was completed about 1880. The cabin is in excellent condition today; a new roof and superstructure were added by the present owner in 1932. Hand-hewn logs, eight to ten inches, refit on a loose rock foundation, and rise to a height of seven feet. Deep notching of the logs made a tight durable corner joint and thus chinking was omitted. A gable of about six feet rises to the ridgepole and is enclosed with vertical boards and bats.

Gin Flat.—The Gin Flat cabin stands about 150 feet east of the old Big Oak Flat road in the south end of the meadow. Actually, there are two separately built cabins placed so close together as to give the appearance of one long unit. The larger unit is 16 by 24 1/2 feet, and the smaller 14 by 18 1/2 feet. There is a common porch 6 feet in depth spanning both structures. Wedge-shaped chinking was inserted between the pine logs which were hewn on the two exposed sides, and secured at the box-notch joints by large oak dowls. Granite was used for the foundation and again for a dry masonry fireplace built in a corner of the larger unit. The perlins are parallel with the sides and covered by a sugar-pine shake roof. The gable is filled in and sealed with vertical boards.

Construction was begun in 1883 by John Curtin, a stockman who had frequented the Gin Flat area since the early seventies. Mr. Curtin lived at Keystone, California, near Knights Ferry.

Kibble.—This structure was erected on the shores of the natural Lake Eleanor by Horace J. Kibbe, a homesteader; the building and its site are now under the waters of the Lake Eleanor reservoir. Very little is known about either Kibbe or his residence. An oldtimer of the Lake Eleanor area, Theodore B. McCleod, when questioned, recalled his first visit to Lake Eleanor in 1877 when he was six years old, at which time Kibbe instructed him in the art of catching trout. McCleod volunteered the information that Kibbe was a “Squaw Man” and had his squaws pack trout from lake to lake, thereby stocking them so the Indians and Kibbe would have good fishing. The cabin consisted of one room and the sides were covered with

[click to enlarge] Biledo cabin (type III) |

Hodgdon Ranch or Branson Meadows.—About two miles within the park on the Big Oak Flat road is the former Hodgdon Ranch. T. J. Hodgdon, a colorful pioneer, was the father of the Jerry Hodgdon who later built the two-story cabin at Aspen Valley, previously described. The site of this ranch was first called Moore and Bowen Camp, then Bronson Meadows. and eventually, when Hodgdon acquired the land, Hodgdon Meadows. T. J. Hodgdon was only twelve years old when he first visited Bronson Meadows, and perhaps this visit instilled in him the desire to own the place. On May 15, 1865, he purchased the land by squatter’s title Hodgdon raised cattle here and two log cabins constituted his first physical improvements.

In 1870 Hodgdon’s ranch was at the end of the Big Oak Flat wagon road. Passengers en route to Yosemite would spend the night at Hodgdon’s and travel in the saddle from that point over the trail to the valley. In 1872, Hodgdon, together with a Mr. Shoup, engaged in a staging business and continued in this enterprise for seven years.

The ranch finally contained a number of buildings, including a hospice for travelers which was completed in 1871. The two early log cabins were tightly constructed of square hand-hewn logs placed on a loose rock foundation and roofed with split shakes. They were chinked with split shakes laid parallel with the building timbers.

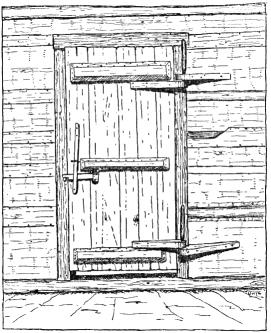

Smith Meadow.—One mile southeast of Smith Peak and Hetch Hetchy Reservoir is a cabin in relatively good condition with only the shake roof in poor repair. Hand-hewn logs were handsomely laid, and the box corners were secured with hardwood dowls driven at an angle to the adjacent log, The cabin is twelve by sixteen feet and rises to a height of thirteen feet six inches. Eight logs approximately twelve inches square constitute the walls. The roof joists are so spaced as to accommodate three-foot shakes and extend five feet beyond the front of the cabin and two feet at the rear. This extension is also covered by shakes. There is an interesting doorway in the front. The door is hung on hand-carved wooden hinges and pivoted on wooden pegs. The wooden latch is so constructed as to allow the occupants to lock the door from the outside. Beveled cross bracing is attached across the upright boards by means of Belgium nails. A small fireplace of dry masonry stone is situated in the rear wall, which appears to be only a blackened niche. The fireplace did boast a mantle, however, held in place and supported by wooden pegs.

Evidently great care was exercised to make this cabin comfortable, for a double chinking was used between the square timbers. From the exterior side, small poles the size of the niche were inserted deeply between the logs, so deeply in fact they can barely be discerned. For further insulation against cold, split shakes were applied over the gap between logs on the interior side, which in addition to affording a double seal also produced a smoother wall surface.

This cabin was built in 1885 by Cyril C. Smith, an early settler in these parts who came from Maine. He had holdings in Merced and settled on lands now known as Mather, Hetch Hetchy, and Smith Meadow, which he used as summer pasturage for his stock. Smith was primarily a sheep man, but did at one time raise hogs on the Mather site. Cyril Smith was the father of Elmer Smith of Merced, who sold parts of these lands to the City of San Francisco for a recreation camp.

Tamarack Lodge.—On the Big Oak Flat Road was a hospice for travelers known as Tamarack Flat Lodge. A photograph taken in 1903 shows the lodge in reasonably good condition. Several bicycles appear in the picture.

[click to enlarge] Door of Smith Meadow cabin |

Split shakes were used to cover the roof and again to chink between the square timbers. They were secured fiat against the logs to produce a good tight seal. The gable was filled in with vertically laid boards. There were two signs over the door, one reading “Tamarack Lodge” and the other “Tamarack Flat.”

Miguel Meadows.—What remains of the Miguel Meadows cabin can be seen seven miles from Hetch Hetchy Reservoir on the Lake Eleanor trail. Presently, the cabin is in a state of collapse and will not be found standing many more winters. From an old photo presented by Celia Crocker Thompson of Lodi, California, it appears that in its younger years the cabin was quite substantial and well constructed to carry the winter burden of heavy snows. Split shakes completely covered the exterior, and hand-hewn timbers were used as structural members. A large dry masonry fireplace and chimney in sound condition still stands.

Miguel Herrara and his partner, Jonas Rusk, owned the meadows. They grazed a large herd of cattle and horses in this area in the summer. Herrara is described as a small man with black hair and dark complexion, and was apparently of Mexican or Spanish descent. In addition to Miguel Meadows, he also had holdings at Lake Vernon at one time.

Beehive.—The second of the two Beehive cabins, seven miles north of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, was also established by the Elwell family as summer headquarters during the grazing season. Large logs were used for this cabin, the first of which was half buried in the ground. Five perlins were laid from the center ridgepole down to the wall height, and these were covered with split shakes. The perlins extended approximately three feet over the front of the cabin to shelter the doorway. This extension was covered with split shakes.

The Elwell family also built cabins on Tiltill Mountain and another near Lake Vernon, but the latter is no longer standing. Very little information is available about this family. However, District Ranger John Bingaman talked to a few of the oldtimers west of the park and learned that the Elwells once lived near Groveland, California, and each summer drove their cattle up into the higher country and returned to their home range in the fall. These cabins were built in this period. About 1889, Mr. and Mrs. Thomas R. Reid filed on Lake Vernon by preemption and built a cabin there. At the same time, Lewis Elwell filed on Mount Gibson and Eugene Elwell field on Beehive.

McCauley.—One of the more recent of the log cabins in Yosemite, John McCauley’s in Tuolumne Meadows. Many modern features are found in this building but they do not conceal its original character. Round logs were used and the corner joints were square or box notches. It stand on a rock foundation, and the chinking is mortar. Alterations include a shingle roof with flashing, screen door, and glass windows.

McCauley built this cabin about 1912, probably before actually acquiring title to the land which he purchased from Jean B. Lembert, who had obtained a homestead patent here in 1895. Soon thereafter the Sierra Club acquired the property from McCauley.

[click to enlarge] Tuolumne Meadows cabin |

Tuolumne Meadows.—This small house is on the Elizabeth Lake Trail in Tuolumne Meadows and is in reasonably good condition. It was roughly and crudely constructed of unusually large lodgepole timbers, extending from the base log on the ground to a height of approximately nine feet at the ridgepole. Entrance is gained through a doorway about five feet in height at the left side of the fašade. The manner in which the logs were joined at the corners produced a fairly tight cabin, thus minimizing the need for chinking. However, some chinking, in the form of small wedges placed parallel between the logs, was used in places.

Although round logs were utilized, the corner joints were secured with a box corner. Only two courses of long shakes were used on the roof, which produced a shabby appearance.

Information regarding the cabin’s historical background is sparse. Mr. William E. Colby, who has long known the Tuolumne Meadows area, states that the cabin was there in 1894 to his best recollection, and that it was built by one of the sheepherders who used to drive sheep into the meadows prior to the establishment of Yosemite National Park.

Devil’s Postpile.—Southeast of Yosemite National Park is the Devil’s Postpile National Monument. It is stated in Gudde’s California Place Names that Red Satcher, a sheepherder, settled in this area about 1878. He built a cabin with a large fireplace at the foot of the Devil’s Postpile, easily accessible from the pasturage in the immediate vicinity. Mr. Douglas Robinson of Bishop, California, states that he visited this area in 1909 and that a Mr. Moore was living in the cabin. At that time, the structure was in good repair, indicating that possibly Mr. Moore had rehabilitated it.

Architecturally this cabin has some features not found in most of the early pioneer structures. Large logs were used at the base and as the walls proceeded upward, smaller elements were employed. This produced a sturdy appearance. The doorway and windows were deeply recessed and boxed in by cut lumber. Shake and wedge-shaped chinking were used. At the present time the structure is in a state of collapse, but all of its parts are recognizable.

The additional cabins listed below are known to have been of log construction. Pertinent information on structural features and historical data are not available; they are only mentioned to record their approximate location and to solicit information from readers who may know something about them.

Buck Camp.—East of Wawona. The cabin no longer stands but remains of it were seen by District Ranger John W. Bingaman in the early 1920s.

Cathawood.—In Zip Canyon along the South Fork of the Merced River below Cunningham Flat. Reported by Frank Ewing.

Empire Meadow.—The original cabin was built near the road that leads to Deer Camp, southeast of Chinquapin Ranger Station.

Hazel Green.—West of Yosemite National Park on the Coulterville Road.

Lake Vernon.—Built on the shores of Lake Vernon by Thomas R. Reid in 1889.

Little Yosemite.—In Little Yosemite Valley. Probably belongs in the group of early National Park Service cabins mentioned under Crane Flat.

Ostrander.—Stood near the present Bridalveil Creek Campground.

Rancheria Mountain.—Above Hetch Hetchy on Hat Creek near the the trail crossing.

Turner Meadow.—Stockman’s cabin four miles below Crescent Lake, east of Wawona.

Westfall.—Built by J. J. Westfall on Bridalveil Creek, south of the present Glacier Point Road.

These notes serve to crystallize the thought that even the back country of this, the oldest and one of the great scenic reservations in America, did not escape exploitation. Now, as we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the discovery of Yosemite Valley, we can take satisfaction in the fact that most of the pioneers who occupied their chosen spots in the area which became Yosemite National Park did not bring about such changes as would menace the integrity and values of the preserve. Miners made but feeble scratches as they sought mineral deposits which were never found; sheepmen and cattle ranchers were a very real threat and it is impossible to state accurately the extent of damage done to land and flora, but their period of activity was brought to an end before a great deal of irreparable damage was done; trappers were present but they have left little trace of their activity; homesteaders, generally, wreaked no havoc—their claims with few exceptions have reverted to nature. Two of the exceptions exist in the Hetch Hetchy reservoir and the artificially enlarged Lake Eleanor. Some of the lands acquired by Horace J. Kibbe, J. L. George, M. A. Wheaton, C. C. Smith, Horatio and Eveline Kellett, Nathan Screech, Joseph Screech, George Marshner, and Thomas R. Reid were purchased by the City and County of San Francisco and are now embraced, together with some National Park Service lands, in the Hetch Hetchy water project. Other lasting effects of private ownership are seen in the Wawona area where a section of land in the park now provides homesites for several hundred people. At Foresta near the west boundary of the park a somewhat similar condition has developed on lands which were the homesteads of James M. McCauley and Thomas A. Rutherford. At Aspen Valley and in East Meadow, owned by the Hodgdon Estate considerable timber has been cut, as is also the case on a quarter section near Wawona which originally was patented by Emily V. Dodge. The National Park Service has been quite successful in buying most of the other private holdings touched upon in this account.

All in all, there is little or no mark of the pioneer owner to be found upon these lands other than the old cabins which are slowly melting into the ground from which they sprang.

Pioneer cabins in Yosemite National Park |

My deep appreciation is extended to my wife for her cooperation and to Superintendent Carl P. Russell for his many hours of laborious work in gathering material and for instigating this article. Also my gratitude to Assistant Chief Ranger Homer Robinson for information freely given, and to the following men who have obtained data, measurements, and photographs of some of the early cabins: District Rangers Louis W. Hallock, John W. Bingaman, Samuel L. Clark, Harry R. During and Carl Danner; Park Rangers Kenneth R. Ashley, John Wilbur and C. A. Walquist; Park Forester Emil F. Ernst provided comprehensive data regarding land titles and Information Specialist Ralph H. Anderson made available his many photos of pioneer structures. I have obtained assistance, also, from the Yosemite Museum staff in locating certain photographs and manuscripts preserved in the Yosemite Museum Library. To Chief Ranger Oscar Sedergren I express appreciation for the coordination he has given to field studies and to my work in compiling this material.

Museum Echoes, April 1950.

One Hundred Years in Yosemite, 1947, by Carl P. Russell.

Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Oct. 1949.

Standard Oil Bulletin, May 1931.

United States Department of the Interior Park and Recreation Structures, 1938.

Yosemite Nature Notes, June 1949.

Robert F. Uhte (pronounced “You-tay”) was born December 28, 1923. His mother Dorris Hallock later married Yosemite Ranger Lou Hallock. His obituary mentions he

Enlisted and commissioned in U.S. Naval Aviation from Dec. 7, 1942 through Apr. 16, 1945. Graduated from UC Berkeley in 1954 with a degree in architecture [Sacramento Bee (June 2012)]

Uhte became a Seasonal Ranger in Yosemite in 1948 and a Park Ranger in 1950. While a ranger he gathered information on pioneer cabins based on field notes of several park rangers in 1949 and 1950. He was particularly interested in the architecture of the cabins. He transferred to the NPS Region Four Office, San Francisco in 1951. During 1955-1964 Uhte was California State Parks architect, where he was a prominent designer. His design philosophy was that structures fit into their environment instead of calling attention to themselves. He also incorporated the concrete block as a major component of his designs. He retired in 1981 and lived in Citrus Heights, California.

Uhte died June 11, 2002 in California.

Robert F. Uhte (1923-), “Yosemite’s Pioneer Cabins,” Sierra Club Bulletin 36:49-71 (May 1951). Illustrated “with drawings by the author.” Library of Congress Call Number F868.S5 S5 v.36.

This article was reprinted, possibly with revisions, as “Yosemite’s Pioneer Cabins,” Yosemite Nature Notes 35(9):135-43 and 36(10):144-55 (September and October 1956).

Digitized by Dan Anderson, October 2006,

from a copy at UCSD Library.

These files may be used for any non-commercial purpose,

provided this notice is left intact.

—Dan Anderson, www.yosemite.ca.us

| Ebook formats | No images: | Plain text zip | Plucker | HTML zip | Palm Doc | Palm zTXT | Sony LRF | Braille Grade 2 BRF |

| Images: | Plucker | iSilo | Kindle/Mobipocket |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemites_pioneer_cabins/