| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > 100 Years in Yosemite > Guardians of the Scenes >

Next: Documents • Contents • Previous: Interpreters

|

|

|

| Woodcut from the first edition (1931) |

In the body of Indian fighters who first entered Yosemite Valley, there appears to have been but one man who sensed the possibilities of public good to be derived from the amazing place just discovered. A year prior to the entry of the Mariposa Battalion, L. H. Bunnell, in climbing the trail from Ridley’s Ferry (Bagby) to Bear Valley, had descri[b]ed in the eastern mountains an immense cliff which, apparently, loomed, column-like, to the very summit of the range. He looked upon the “awe-inspiring sight with wonder and admiration, and turned from it with reluctance to resume the search for coveted gold.”

When, on March 25, 1851, Bunnell stood at Inspiration Point with other members of Savage’s command and gazed upon the extravagance of natural wonders, he recognized “the immensity of rock” which had, the previous year, astonished him from afar. He writes:

Haze hung over the valley—light as gossamer—and clouds partially dimmed the higher cliffs and mountains. This obscurity of vision but increased the awe with which I beheld it, and as I looked, a peculiar exalted sensation seemed to fill my whole being, and I found my eyes in tears with emotion.

He withdrew from the trail and stationed himself on a projecting rock, where he might contemplate all that was spread before him. Major Savage, bringing up the rear of the column, brought him out of his soliloquy in time to join the battalion in its descent to the floor of the valley. The party that night discussed the business of naming the valley as they sat about their first campfire, near the foot of Bridalveil Fall. Bunnell comments:

It may appear sentimental, but the coarse jokes of the careless, and the indifference of the practical, sensibly jarred my more devout feelings, while this subject was a matter of general conversation; as if a sacred subject had been ruthlessly profaned, or the visible power of Deity disregarded.

Bunnell’s later discussions with residents of the Mariposa hills and his very tangible evidence in the form of personal funds expended on the Coulterville trail to Yosemite, indicate that he was the first to strive for public recognition of the assets available in the new scenic wonderland. Other men of the region were understandably slow to develop aesthetic appreciation for that which only thrilled and produced no gold.

By 1855 rumor and conjecture regarding the mysteries of the valley had created sufficient interest among the old residents and the many newcomers in the mining camps to prompt fascination in J. M. Hutchings and his story when he returned to Mariposa after his first “scenic banqueting” under Yosemite walls. With the publication of the Hutchings articles and the Ayres drawings, curiosity may be said to have become general, and the trek to the valley was started.

The entire mountain region was, of course, public domain, and, though it had not been surveyed, it was generally conceded that preëmption claims could be made upon it. Homesteaders were establishing themselves in numerous mountain valleys above the gold region, and such “squatting” was done with the assent of state and federal officers. It is hardly surprising that some local aspirants laid claim to parts of Yosemite Valley. The company that expected to develop a water project in 1855 was apparently the first to attempt to establish rights. Then came the series of would-be hotel owners, whose activities have been described. James C. Lamon was a mountaineer who came to Yosemite in 1859 and aided in the building of the Cedar Cottage. While so engaged, he established himself in the upper end of Yosemite Valley and there developed the first bona fide homestead by settlement. For many years his log cabin was a picturesque landmark in the valley, and today two orchards near Camp Curry serve as reminders of his pioneering.

With the advent of the ’sixties California began to recognize the aesthetic value of some of her mountain features. The acclaim of leaders from the East and the expressed wonder of notables from abroad played a part in the development of a state pride in the beauties of Yosemite, and, gradually, it became apparent that only poor statesmanship would allow private claims to affect an area of such world-wide interest.

On March 28, 1864, Senator John Conness,1 [ 1Mount Conness, one of the outstanding peaks in the Tuolumne Meadows region, was named for Senator John Conness by Clarence King, later first director of the United States Geological Survey, but at the time a member of the Whitney Survey. King and James T. Gardiner were the first to climb the peak, making the ascent in 1864. Referring to the mountain, King said that because of its “firm peak with titan strength and brow so square and solid, it seems altogether natural we should have named it for California’s statesman, John Conness.” ] of California, introduced in the U. S. Senate a bill to grant to the State of California tracts of land embracing the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees. On May 17, his bill was reported out of committee. On the occasion of the debate which followed, Senator Conness entered into the record of American conservation the first evidences of national consciousness of park values as we conceive of them today. He started the long train of legislative acts which have given the United States the world’s greatest and most successful system of national parks. It is a fact, of course, that the Senate action of 1864 did not create a national park but it did give Federal recognition to the importance of natural reservations in our cultural scheme, and charged California with the responsibility of preserving and presenting the natural wonders of the Yosemite.

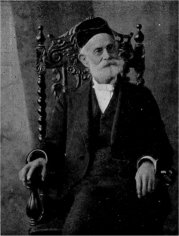

John Muir |

By George Fiske Galen Clark |

Colonel H. C. Benson |

James M. Hutchings |

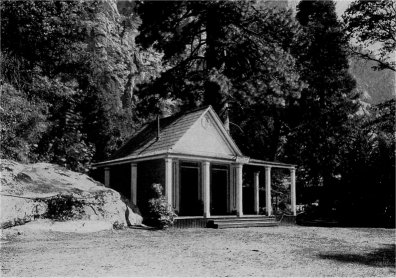

By J. N. LeConte Sierra Club Headquarters in Yosemite, 1898 |

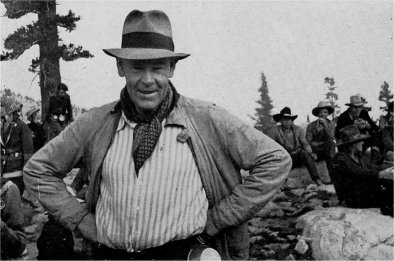

By Ansel Adams William E. Colby |

Senator Conness explained to the Senate that it was the purpose of his bill “to commit them [Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees] to the care of the authorities of that State for their constant preservation, that they may be exposed to public view, and that they may be used and preserved for the benefit of mankind. . . . The plan [of preservation] comes from gentlemen of fortune, of taste, and of refinement. . . . The bill was prepared by the commissioner of the General Land Office, who also takes a great interest in the preservation both of the Yosemite Valley and the Big Trees Grove”2 [ 2Congressional Globe, May 17, 1864, p. 2301. ]

The bill was passed by the Senate on May 17, referred to the House Committee on Public Lands on June 2, debated and passed by the House on June 29, and signed by President Lincoln on July 1, 1864. These deliberations, which designated the first scenic reservation for free public use, were consummated under the stress of waging war.

In order to eliminate friction and delays in the operation of legislative machinery, proponents of the Yosemite bill secured its passage without recognition of the private claims made by Yosemite settlers. Lamon, clearly a bona fide homesteader; Hutchings, who had a short time before the passage of the act purchased the Upper Hotel property; Black, the owner of Black’s Hotel; and Ira Folsom, interested in the Leidig property, pressed their claims and involved the new state park in prolonged litigation.

The State Park Act provided that the Yosemite Grant and the Mariposa Big Trees should be managed by a board of commissioners, of whom the governor of the state was to be one. On September 28, 1864, three months after the grant was made, Governor F. K. Low proclaimed that trespassing upon the tracts involved must desist. His board of Yosemite commissioners was appointed in the same proclamation.

Frederick Law Olmsted, even then an accomplished landscape architect, was made chairman of the board. As Brockman (1946, p. 106) has revealed in his article on Olmsted, the chairman was also the first administrative officer of the Yosemite Grant. Olmsted’s statement of 1890 substantiates this fact: “I had the honor to be made chairman of the first Yosemite Commission, and in that capacity to take possession of the Valley for the State, to organize and direct the survey of it and to be the executive of various measures taken to guard the elements of its scenery from fires, trespassers and abuse. In the performance of these duties I visited the Valley frequently, established a permanent camp in it and virtually acted as its Superintendent.”

Legal acceptance of the gift could not be made until the next session of the state legislature. On April 2, 1866, the necessary provisions for administration were secured. The board of commissioners made the best possible selection of a guardian, the Yosemite pioneer, Galen Clark, and invited the settlers of the valley to vacate their holdings.

J. M. Hutchings, as might be expected, was wrathy. It is probable that James Lamon, after eight years of permanent residence on his land, saw no justice in the act. The other claimants held out for what might be in it. Hutchings and Lamon refused to surrender their property, and a test suit was brought against Hutchings, which was decided in his favor. This was carried to the supreme court of the state and then to the federal Supreme Court. In these last actions the commissioners were sustained. That Hutchings and Lamon were deserving of consideration and remuneration cannot be denied, but millions of Americans are today indebted to the board of commissioners who pursued the case to a settlement favorable to the people. Private titles of the type held by the Yosemite Valley settlers would have been disastrous to all administration in the years that were to come.

On the other hand, Hutchings and Lamon were deserving of certain sympathy. No man had done more than J. M. Hutchings to call attention to the fact that the Yosemite was a wonderland, eminently worthy of the distinction bestowed upon it by the state. For a decade prior to the creation of the state park, he had devoted himself to disseminating knowledge on its “charming realities.” Much of this was done through his California Magazine and the lithographic reproductions of the Ayres drawings. Some of it was accomplished with his volume, Scenes of Wonder, which ran through several editions. The many published testimonials of his worth as guide and informant while operating his Hutchings House in Yosemite Valley indicate that his efforts to engender a public love for the place were not spared even after his difficulties arose with the state. And, finally, during the ten-year fight for reimbursement he lectured throughout the country, bringing home to the dwellers in Eastern cities the fact that a phenomenally beautiful area in California was worthy of their visit. Some of the manuscripts of these Eastern lectures are possessed by the Yosemite Museum. Their text reveals none of the commercialism and selfishness with which Hutchings sometimes has been charged.

The earnest efforts which Hutchings had expended in interesting the public in Yosemite had not failed to create an interest in him as well. The court had refused further consideration of the claims of the settlers, but the state legislature, influenced by public feeling and the expressed approval of the Yosemite commissioners, appropriated $60,000 to compensate the four claimants. Of this Hutchings received $24,000; Lamon, $12,000; Black, $13,000; Folsom, $6,000, and the remaining $5,000 was returned to the State Treasury. Because of this prolonged litigation, the commissioners did not secure full control of the grant until 1875.

To what extent such troubles would dissipate the best directed efforts of a board of managers of any business can well be imagined. Further difficulties developed when road privileges were granted. The state legislature failed to sustain the position of the commissioners in the matter of exclusive rights for a road on the north side of the valley, and again a controversy arose which directed heated criticism upon the management of the state park. Public hostility alternated with general indifference. The state failed to provide adequate funds with which to accomplish the important work before the commissioners, and the lack of a well-defined policy handicapped the administration to a point of ruin. In 1880 a new law removed the first board and appointed a new one.

The next decade saw important developments take place in the park, but policies adopted were sure to displease someone or some faction. Criticism still prevailed. Gradually the seethings of the press brought about the development of intelligent public interest in Yosemite affairs. Indifference was replaced by discriminating attention, and Yosemite administration arrived in a new era.

In these pages not enough has been said about John Muir. His contributions to the preservation of Yosemite National Park, to the determination of scientific facts regarding it, and to public understanding of its offerings place him in the front rank of conservationists who have been instrumental in saving representative parts of the American heritage. The role he played as explorer, researcher, interpreter, and defender of the public interests in the Yosemite may well become the subject of another book of Muiriana; however, at this juncture, it is only possible to relate him rather inequitably to the field of Yosemite administrative history.

John Muir arrived in Yosemite for the first time in 1868. Intent upon making deliberate studies of all that fascinated him, he determined to remain a resident of the Yosemite region. In order to do so, he attached himself to a sheep ranch. He gave the first winter to work on the foothill ranch and the next summer to herding in the Yosemite Sierra. With the intimate acquaintance so made with sheep and their ways, he was destined to create a wave of public interest in Yosemite that would eclipse all former attentions and revolutionize the administrative scheme.

For eight years after his first Sierra experience, John Muir rambled over his “Range of Light.” He tarried for some time in Yosemite Valley and was employed by J. M. Hutchings, at times, to operate a sawmill, which Muir immortalized merely by inhabiting it.

Some impression of his first employment in Yosemite Valley and his early outlook upon the Yosemite scene may be gained from these paragraphs of his memoirs published by Badè3 [ 3The Life and Letters of John Muir, I: 207-108. ] “I had the good fortune to obtain employment from Mr. Hutchings in building a sawmill to cut lumber for cottages, that he wished to build in the spring, from the fallen pines which had been blown down in a violent wind-storm a year or two before my arrival. Thus I secured employment for two years, during all of which time I watched the varying aspect of the glorious Valley, arrayed in its winter robes; the descent from the heights of the booming, out-bounding avalanches like magnificent waterfalls; the coming and going of the noble storms; the varying songs of the falls; the growth of frost crystals on the rocks and leaves and snow; the sunshine sifting through them in rainbow colors; climbing every Sunday to the top of the walls for views of the mountains in glorious array along the summit of the range, etc.

“I boarded with Mr. Hutchings’ family, but occupied a cabin that I built for myself near the Hutchings’ winter home. This cabin, I think, was the handsomest building in the Valley, and the most useful and convenient for a mountaineer. From the Yosemite Creek, near where it first gathers its beaten waters at the foot of the fall, I dug a small ditch and brought a stream into the cabin, entering at one end and flowing out the other with just current enough to allow it to sing and warble in low, sweet tones, delightful at night while I lay in bed. The floor was made of rough slabs, nicely joined and embedded in the ground. In the spring the common pteris ferns pushed up between the joints of the slabs, two of which, growing slender like climbing ferns on account of the subdued light, I trained on threads up the sides and over my window in front of my writing desk in an ornamental arch. Dainty little tree frogs occasionally climbed the ferns and made fine music in the night, and common frogs came in with the stream and helped to sing with the Hylas and the warbling, tinkling water. My bed was suspended from the rafters and lined with libocedrus plumes, altogether forming a delightful home in the glorious Valley at a cost of only three or four dollars, and I was loath to leave it.”

When he was not running Hutchings’ mill, he was making lonely trips of discovery or guiding visitors above the valley walls. Perhaps Muir knew of the use he would make of the natural history data he was gathering, but few of his associates sensed the fact that he would soon make the nation quicken with new views of Yosemite values.

He first made his influence felt in the early ’seventies, when he began publishing on Yosemite in journals and periodicals. His material awakened responses everywhere. On February 5, 1876, he published an article in the Sacramento Record Union which was one of the initial steps in his forceful appeal to America to save the Yosemite high country from the devastations of sheep and the incendiary fires of sheepherders.

It is likely that few who today enjoy the Yosemite High Sierra realize that sheep, “hoofed locusts,” were responsible for the creation of Yosemite National Park. The people of California, awakened to the danger by the warnings of Muir and others, attempted to secure an enlargement of the state park. Selfish local interests frustrated the plan. In 1889, John Muir allied himself with the Century Magazine, and a plan was launched which was designed to arouse a public sentiment that could not be shunted. Muir produced the magic writings, and Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of the Century, secured the support of influential men in the East. On October 1, 1890, a law was enacted which set aside an area, larger than the present park, as “reserved forest lands.” Within this reserve were the state-controlled Yosemite and Mariposa Grove grants.

The reactions of residents of the regions adjacent to the new national park to this legislation was typical of the period. Citizens of the counties affected could not foresee the coming of unbroken streams of automobile traffic, which eventually would bring millions of dollars to their small marts of trade. The thought of losing some thousands of acres of taxable land caused county seats to seethe with unrest. The local press painted pictures of dejected prospects and near ruin. The following summary of a lengthy wail from a contemporary paper reveals the fears that prevailed:

Let us summarize the result of our analysis. On the one side, we have 932,600 acres of land taken away from the control and use of the people at large, and of the people of Mariposa, Tuolumne, Mono, and Fresno counties in particular, for the ostensible purpose of preserving timber, mineral deposits, and natural curiosities or wonders within said reservation—for whose benefit, the act does not say, but presumably for the benefit of tourists.

On the other side, we find: That the avowed object of preserving forests appears to be only a false pretense to cover up the real object of the scheme, whatever it may be—that to preserve mineral deposits will prevent untold treasures from being employed in industry and commerce, and prevent the employment of thousands for many years to come in the exploration of these mineral deposits— that to preserve natural curiosities and wonders, it is not necessary to fling away nearly a million acres of land, when all that is necessary can be accomplished by attaching to each wonder as much land, as, through natural formation, contributes in any measure towards its maintenance—that, if on the one hand, these claims are respected, it will condemn hundreds of American settlers to poverty, if, on the other hand, these claims are bought out, it will entail an expense of many millions on the country, whilst the claimants, themselves, will never receive anything like the amount their properties would be worth, in the course of time, if this part of the country is left to its own development without Government interference, and all the settlements now existing will be left to fall into decay and ruin, or will have to be worked by a system of tenantry, a curse, as contemporary history shows, which ought never be allowed to take root in our country.

The preservation of the full watershed of the Yosemite Valley is not only a legitimate, but a desirable object; the same holds good with the Hetch-Hetchy Valley, or any other grand work of nature. Every alienation of land, beyond this, is of evil.

This local feeling resulted in immediate attempts to change the park boundaries. The first attempt was frustrated largely through the efforts of the Sierra Club. This organization came into existence shortly after Yosemite National Park was created and has always been one of the most important agencies that have promoted the safety of Yosemite treasures. Its publication, the Sierra Club Bulletin, which first appeared in 1893, is a rich source of Yosemite history. For twenty-two years John Muir was the president of the club. His vim in leaping to the defense of the great natural preserve was no less than had been his vigor in working for its creation. Muir aided in the preservation of national monuments as well. In early May, 1903, Theodore Roosevelt, then president, visited Yosemite via Raymond and the Mariposa Grove. Governor George C. Pardee, Benjamin Ide Wheeler, president of the University of California, and John Muir were among those who interpreted the scene for the President. Conservation matters were discussed by Muir and the legislation which was to become famous as the Antiquities Act of 1906 was given some definition at this time. It was truly an important occasion.

Chief among the Sierra Club defenders of Yosemite who have carried on since the death of Muir is William E. Colby. He served forty-four years as secretary of the organization, two years as president, and is now, as a director, a frequently sought source of counsel. He led the club’s summer outings for more than three decades. Throughout this period Colby has unceasingly built the Sierra Club’s prestige in the field of conservation. For the past six years he has served as a member of the Yosemite Advisory Board, and has been in close touch with past and current park problems.

The failure of the national government to provide funds with which to extinguish private claims within the park involved the administration in difficulties which are being felt even yet. By 1904 relations between administrative officers and the large number of owners of private holdings had become so strained that legal action was imperative. Boundary revisions were required. Major Hiram M. Chittenden headed the commission appointed to investigate possible boundary changes. Upon the recommendation of this commission large areas on the east and west were lopped off. In 1906 a tract on the southwest was cut off, and since that time small changes have been rather numerous. Private lands still exist within the park and constitute an ever-present source of trouble.

From the first the control of Yosemite National Park has been vested in the Secretary of the Interior. Immediately after the passage of the act of creation, military units were detailed to take charge of all national park lands. The state retained its plan of administration of the original Yosemite Grant, and so came about the dual control which for sixteen years colored the Yosemite administration with petty misunderstandings and hindered progress in the maintenance of the entire region.

Galen Clark’s old ranch (Wawona) became headquarters for the Acting Superintendent of the federal preserve. From this eccentric hub, patrols of cavalrymen were sent into the unbounded wilderness area of the new preserve. A trail system and accurate maps did not exist. One of the first undertakings of the early superintendents was to make the rough country accessible by horse trail. The topography was studied, and a good map was prepared. Following the practice established in Yellowstone National Park, patrolling stations were established, and the United States Army had the safety of Yosemite’s fauna and flora fairly within its keeping.

Since pioneer days, sheep and cattlemen had enjoyed unrestricted use of the excellent range which was now forbidden them. Naturally they were reluctant to abandon it. Their trespass was the most formidable threat with which the troopers were confronted, and concerted, ingenious work was necessary to expel the intruders. When the first culprits were taken into custody, it was found that no law provided for their punishment. Congress had failed to provide a penalty for the infraction of park rules. Nothing daunted, the superintendents put the captured herders under arrest and escorted them across the most mountainous regions to a far boundary of the park. There they were liberated. The herder’s sheep were driven out of the reserve at another distant point. By the time the herder had located his animals, his losses usually were so great as to represent a more severe punishment than could have been meted out by the court had the law applied. Several years of this practice caused neighboring ranchers to keep their animals out of the forbidden territory.

Captain Abram Epperson Wood was the first superintendent. With detachments from the Fourth Cavalry he arrived in the park on May 19, 1891, and continued in charge until his death in 1894. Each year the troopers came in April or May and withdrew in the fall. During the winter two civilian rangers attempted to patrol the area. With such inadequate winter protection, it is small wonder that poachers grew to feel that the wild life of the reserve was their legitimate prey. It was not until 1896, in fact, that a determined effort was made to keep firearms out of the park at any time of the year.

For twenty-three years the Department of the Interior continued to call upon the War Department for assistance in administering Yosemite National Park. Eighteen army officers took their turn at the helm. Some of them assumed leadership after some years of Yosemite experience as subordinate officers. Others were placed in command with no previous service in the park. Lieutenant (later Colonel) Harry C. Benson and Major W. W. Forsyth were perhaps the most distinguished of the superintendents. Benson was certainly more than a superintendent; he was an explorer, map maker, trail builder, fish planter, and nemesis of the sheepmen. Among the subordinate officers and enlisted men a number left their mark by way of accomplishments. N. F. McClure and Milton F. Davis are remembered for their explorations and excellent map making. William E. Breeze and W. R. Smedberg worked with McClure and Benson in stocking the headwaters of the Yosemite rivers with trout. A. Arndt pioneered in exploration of some of the northern sections of the park. Many others in the military organizations are remembered in place names throughout the Yosemite High Sierra.

Yosemite was fortunate in having within its National Park Service personnel one man, Gabriel Sovulewski,4 [ 4Gabriel Sovulewski was born in Poland in 1866; he died Nov. 29, 1938. For a synopsis of his work and the activities of others in the military administration, see “Administrative Officers of Yosemite,” by C. Frank Brockman, Yosemite Nature Notes (1944). ] who pioneered with these army units and who was acting superintendent of the park in 1908-1909 and again in 1914. For thirty-five years Mr. Sovulewski was actively engaged in caring for Yosemite. An unpublished manuscript on his National Park Service experiences is preserved in the Yosemite Museum. Within it he comments upon the Yosemite work of United States troops.

National Parks in California, and Yosemite especially, owe much to the late Colonel H. C. Benson. No one who has not participated in those strenuous years of hard riding and incessant fighting of natural and human obstacles can ever realize the need for indomitable spirit and unselfish devotion to a cause that existed during those first years in Yosemite National Park. Sheep and cattle overran the country. They were owned by men who knew every foot of the terrain. We were ordered to eliminate them. There were few or no trails, and maps did not exist. Reliable guides were unobtainable, and we had more than a thousand square miles to cover.

Officers with detachments set out upon patrols that would keep them away from our base of supplies for thirty days at a time. Many times rations were short, and sixteen to twenty hours of action per day, covering sixty miles in the saddle was not unusual. Constant hammering at the offending cattlemen continued for several years, and at last they were convinced that they must vacate the territory set aside for National Park purposes. The would-be poachers and the entire countryside were taught a moral lesson which still has its effect today. Some of the present-day administrative problems are made easier because of the foundation laid in those first years of the park’s existence.

The duplication of effort and expense which resulted from the anomaly of state and federal administration within the reserve brought about controversies which finally caused many Californians to conclude that their Yosemite State Grant of 1864 might well be placed in the hands of the federal government, to be managed by the same officers who controlled the surrounding national park. The Sierra Club and many civic organizations took the lead in urging recession. Not a few citizens felt that the proposed move was an affront to state pride. This group proved to bean obstacle but was overcome in 1905, when the state legislature re-ceded to the United States the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove. A formal acceptance by Congress brought the Yosemite State Park to an end on August 1, 1906. Major Benson removed military headquarters from Camp A. E. Wood (Wawona), and Fort Yosemite came into existence on the site of the present Yosemite Lodge.

For seven years the administrative organization set up by the military continued to function. The succeeding superintendents found their responsibilities increased considerably. Other national parks were coming into existence, and a national conscience was beginning to recognize the value of wilderness preserves. In 1910 the American Civic Association had launched a campaign for the creation of a national park bureau. President Taft favored central administration of the parks, and bills were introduced creating such a bureau. Major William T. Littebrant was in command in Yosemite when Dr. Adolph C. Miller, a civilian, became assistant to Secretary Lane and was placed in charge of the national parks. The next year troops did not come to Yosemite. Mark Daniels was made superintendent, and civilian employees undertook the work that had been done by the troopers.

A few civilian rangers had assumed the care of the park each winter when troops were withdrawn. Archie O. Leonard had been the first of these and he remained in the service when the administrative change was made. In 1914 “park rangers” came into existence under authorization of Secretary Lane. They patrolled the park as had the troopers, but, unlike the troopers, they remained in touch with their problems throughout the year.

In 1916 Congress created the National Park Service. Dr. Miller, in the meantime, had been called to other work, and Stephen T. Mather, who had followed Dr. Miller as assistant to the secretary, was made Director of the National Park Service. He was authorized by law to “promote and regulate the federal areas known as the national parks, monuments, and reservations.” Conservation of scenery and wild life of the areas was declared by Congress to be a fundamental purpose of the new organization. Mr. Mather’s first undertaking was to balk exploitation schemes. Unfortunately, Yosemite had already been raided. In 1913 Congressman John E. Raker had introduced a bill granting to San Francisco rights to the Hetch Hetchy as a water reservoir. Secretary Garfield had opened the way to this move in 1908. In spite of much opposition, the Raker Bill was passed by the House and Senate and approved by President Wilson. Since that time the Hetch Hetchy dam has become a reality and provides all the administrative difficulties and troubles that were expected.5 [ 5 Taylor, Mrs. H. J. “Hetch Hetchy Water Flows into San Francisco.” Yosemite Nature Notes (1934), pp. 89-91, Badè, W. F., “The Hetch Hetchy Situation [Editorial],” Sierra Club Bulletin, 9 (1914): 3, 174. ]

Private holdings in Yosemite were rather large even after the boundary changes of 1905 and 1906 were made. Timber companies possessing tracts of choice forest constituted the greatest menace. Some of these private lands have been bought up, and others have been exchanged.

During 1930 much progress was made in the acquisition of private holdings in the national park. There were 15,570 acres of land involved, which cost approximately $3,300,000. Half of the cost of purchasing these lands was defrayed by John D. Rockefeller, Jr., the remainder coming from the fund provided by Congress for the acquisition of private holdings in national parks.

The following statements regarding timber holdings in and near Yosemite National Park are taken from the Report of the Director of National Park Service for 1930:

It is impossible to overestimate the importance of this Yosemite forest acquisition. It brought into perpetual Government ownership the finest remaining stands of sugar-pine timber in the area and reduced the total area of private holdings in that park to 5,034 acres. This total will be materially reduced when two pending deals are consummated. A tract containing 640 acres is now in course of acquisition with funds contributed by George A. Ball, of Muncie, Indiana, as is another of about 380 acres, half the funds for the latter transaction being contributed through the co-operation of Dr. Don Tresidder, president of the Yosemite Park and Curry Company.

Additional timber holdings in the Tuolumne River watershed— fine stands of sugar and yellow pine—remain in private ownership outside the park. One cannot help regretting that they are imperiled, and it is hoped by all friends of these majestic forests that they may yet be saved.

In order that the beauty of the Big Oak Flat Road may be unimpaired, arrangements have been made between the Sugar Pine Lumber Co., the Forest Service, the State, and the Park Service to preserve the roadsides through selective cutting of the larger trees and careful removal of any trees that are taken out. Particularly interesting and valuable stands of timber which should be preserved untouched will be made the subject of exchanges between the Forest Service and the Sugar Pine Lumber Co.

This land acquisition program was finally assured of success in July, 1937, when legislation authorized the Secretary of the Interior to acquire the Carl Inn Tract, comprising some 7,200 acres of magnificent sugar pine forest bordering the western boundary of the park. After a year and a half of negotiations with the Yosemite Sugar Pine Lumber Company, owner of most of the tract, agreement was reached on a price of $1,495,500 to be paid by the United States. The purchase was consummated early in 1939. Senator William Gibbs McAdoo and Representative John S. McGroarty, both of California, were the ardent supporters who introduced the bills, S. 1791 and H.R. 5394, in their respective houses.

Policies regarding the toll roads by which tourists could enter the park constituted another perplexing problem with which the young National Park Service was confronted. The routes had been privately constructed and were privately owned and controlled by turnpike companies. Government funds were not available with which to purchase them outright. One company was persuaded to turn the Wawona Road over the the public in exchange for a grant for the exclusive rights to the route during a certain number of years. The government assumed responsibility for the maintenance of the road during this period. The owners of the Coulterville Road could not be persuaded to agree to such a plan. As a result, that part of it which is within the park has not been maintained and, because of erosion, has fallen into disuse.

The Tioga Road had been constructed in 1882—1883 by the Great Sierra Consolidated Silver Mining Company for the purpose of serving the Tioga Mine. The mining venture terminated in 1884 after an expenditure of $300,000 had been made. The road had become impassable during the many years of neglect, but it was still the property of private owners when the region through which it passes became a national park. Stephen T. Mather and some of his friends bought it privately and in 1915 turned it over to the federal government. The state of California purchased the portions of the route which were outside of the park and extended the road eastward, down Leevining Canyon, so giving Yosemite a remarkable high mountain highway, free from toll, which connects Yosemite Valley with the routes of the Mono basin. Tolls were also removed from the Big Oak Flat route. Every effort was made to put all recognized routes in the best of condition consistent with government appropriations. Travel to the park grew apace, and Yosemite had, indeed, entered a new era.

The first scheme of centralized administration of the national park system was promising in theory but proved faulty in practice. More than a few difficulties appeared on the parks horizon. The national preserves were regarded in Washington somewhat as orphans and were not receiving the specialized attention so necessary for their proper administration. The introduction of Mather ideals and methods was required to bring about coordination.

The story is told that one day in 1915 Stephen Mather walked into the office of Secretary Lane and expressed indignation over the way things were run in Sequoia and Yosemite. “Steve,” said Lane, “if you don’t like the way those parks are run, you can run them yourself.” “Mr. Secretary, I accept the job,” was Mather’s rejoinder.

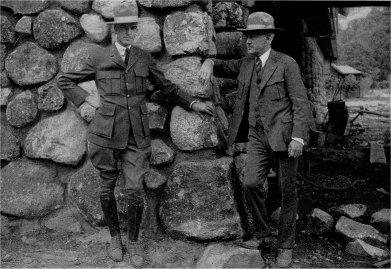

By J. V. Lloyd W. B. Lewis and Stephen T. Mather |

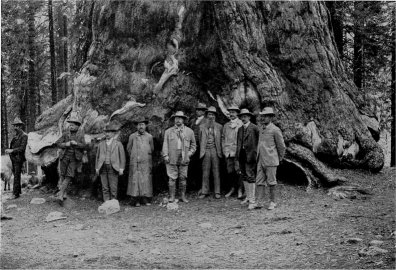

By J. N. LeConte A Presidential Party at the Grizzly GiantPardee Roosevelt Muir Wheeler |

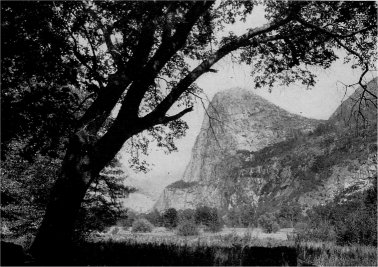

By J. N. LeConte Hetch Hetchy Valley before Inundation |

By J. N. LeConte Devils Postpile, Excluded from Yosemite in 1905 |

The genial Secretary of the Interior showed him into a little office and said, “There’s your desk, Steve; now go to work.” With that Lane went out and closed the door, but presently opened it and said, “By the way, Steve, I forgot to ask what your politics are.”

With such brief preliminaries did Stephen T. Mather assume directorship of the national parks. He served through the presidential administrations of Wilson, Harding, and Coolidge, but the matter of his politics was never inquired into by any party.

Stephen Mather was born on the Fourth of July, 1867, in San Francisco. His ancestry traces back to Richard Mather, a Massachusetts clergyman of the days of the Pilgrim Fathers. Stephen T. Mather was not a scion of wealth. As a young man, he made his way through college by selling books. He graduated from the University of California in 1887 and for several years was a newspaper reporter. Thereafter, he entered the employ of the Pacific Coast Borax Company and was identified with the trade name, “Twenty-Mule Team Borax,” that became well known around the world. For ten years he engaged in the production of profits for his employers and then organized his own company. It was in borax that he built up his business success and accumulated the fortune which “he later shared so generously with the nation through his investments in scenic beauty on which the people receive the dividends.”

For more than twenty-five years Stephen Mather resided in Chicago, Illinois, but his loyalty to his native state, California, never waned. He was the leading spirit in the organization of the California Society of Illinois and, as its secretary, always secured donations of a carload of choice California fruits to be served at the Society’s annual banquets. Mather then saw to it that these affairs were well written up by the press and telegraphed throughout the country on the Associated Press wires. In this publicity the spirit and motives of the present Californians, Inc., had their birth.

As might well be expected, Mather was a member of the Sierra Club and participated in many of its summer outings. (See Farquhar, 1925, pp. 52-53.) He became acquainted with national park areas on these trips, and it is said that his ideal of a unified administration of the parks resulted from the intimacies so acquired. It was his ambition to weld the parks into a great system and to make them easily accessible to rich and poor alike.

At the time Mather undertook his big task, there were thirteen parks. Some of them were difficult of access and provided few or no facilities for the accommodation of visitors. Government red tape stood in the way of action in the business of park development, but Mather cut the red tape. When government appropriations could not meet the situation, he usually produced “appropriations of his own.” It was such generosity on his part which gave the Tioga Road to the government and saved large groves of Big Trees in the Sequoia National Park. In his own office it was necessary for him personally to employ assistants. Because of the lack of government funds, he expended twice his own salary in securing the personnel needed to set his parks machine in operation. The national benefits derived from the early Mather activity in the parks were recognized by Congress, and that body took new cognizance of national park matters. Larger appropriations were made available, and Mather’s plans were put into effect. For fourteen years he gave of his initiative and strength, as well as his money. His ideas took material form, and the park system came into being as he had planned. His work was recognized and appreciated. In 1921 George Washington University bestowed upon him the honorary degree of Doctor of Law. His alma mater, the University of California, conferred the same degree in 1924. President W. W. Campbell on that occasion characterized him as follows:

“Stephen Tyng Mather, mountaineer and statesman; lover of Nature and his fellow-men; with generous and farseeing wisdom he has made accessible for a multitude of Americans their great heritage of snow-capped mountains, of glaciers and streams and falls, of stately forests and quiet meadows.” In 1926 he was awarded the gold medal of the National Institute of Social Sciences for his service to the nation in national parks development. The American Scenic and Historical Preservation Society awarded the Pugsley gold medal in recognition of his national and state park work, and he was made an honorary member of the American Society of Landscape Architects.6 [ 6See Report of the Secretary of the Interior, 1933, pp. 158-159, for account of the Stephen T. Mather Appreciation and the dedication of Mather Memorial Plaques, presented by that organization. ]

In the fall of 1928, Mather’s health failed. He suffered a stroke of paralysis which forced his retirement from public service in January, 1929. For more than a year he fought to regain his strength but in January, 1930, he was suddenly stricken and died quickly. Indeed, “the world is much the poorer for his passing, as it is much the richer for his having lived.”

One of Mather’s first acts as Director of the National Park Service was to appoint a strong man to the superintendency of Yosemite National Park. On the staff of the Geological Survey was an engineer of distinction, Washington B. (“Dusty”) Lewis. Mather appointed him to the Yosemite task and he became the first park superintendent on March 3, 1916. The Yosemite problems were complicated and trying from the beginning. The park was, even then, attracting more visitors than had been provided for. Public demands kept steadily ahead of facilities that could be made available through government appropriations. For more than twelve years W. B. Lewis expended his energy and ingenuity in bringing the great park through its formative stages.

Under his superintendency practically all the innovations which today characterize the public service of a national park were instituted in Yosemite. Motor buses replaced horse-drawn stages; tolls were eliminated on all approach roads; the operating companies were reorganized and adequate tourist occommodations were provided at Glacier Point and Yosemite Valley; a modern school was provided for local children; the housing for park employees was improved; the best of electrical service was made available; the park road and trail system was enlarged greatly and improved upon; the construction of an all-year highway up the canyon of the Merced made the park accessible to a degree hardly dreamed of; provision of all-year park facilities met the demands of winter visitors; a new administrative center was developed; the Yosemite High Sierra Camps were opened; and an information service was devised. The ranger force was so organized as to make for public respect of national park ideals and personnel. The interpretive work, which makes for understanding of park phenomena and appreciation of park policies, was initiated in Yosemite and has taken a place of importance in the organization of the entire national park system.

In short, the present-day Yosemite came into existence under the hands of Lewis and his assistants. How well the demands of the period were met and future requirements provided for is evidenced by the continued healthy growth and present success of the Yosemite administrative scheme.

In the fall of 1927 Lewis was stricken by a heart attack. He later returned to his office, but in September, 1928, it became apparent that he should no longer subject himself to the strain of work at the high altitude of Yosemite Valley. He removed to West Virginia, and there partly regained his strength. Director Mather then sought his services as Assistant Director of the National Parks, and in that capacity he functioned until the summer of 1930. His physical strength, however, failed to keep pace with his ambitious spirit, and after another attack, he died at his home in a Washington suburb on August 28, 1930.

Soon after Lewis accepted his Washington appointment, Director Mather experienced the breakdown which brought about his resignation as Director. There was but one man to be thought of in connection with filling the difficult position. That man was Horace M. Albright, who had been Mather’s right-hand man since the National Park Service had existed. A native of Inyo County, California, and a graduate of the University of California, he became an assistant attorney in the Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C., in order to advance his learning, and there took a keen interest in plans then developing for the establishment of the National Park Service. He was detailed to work in connection with park problems and had already become familiar with them when Stephen T. Mather assumed their directorship. The Secretary of the Interior assigned him to Mather as a legal aid, which position quickly grew in responsibilities as the two men became acquainted. From the first, Albright was the Director’s chief reliance, and when the National Park Service was organized in 1916, he was made Assistant Director. In 1917, 1918, and 1919 he aided in the creation of Mount McKinley, Grand Canyon, Acadia,7 [ 7 At that time called Lafayette National Park and since re-named when it was extended to include a portion of the mainland. ] and Zion national parks. At twenty-nine, he was made superintendent of the largest of all parks, Yellowstone, and in addition shouldered the job of Field Director of the Park Service. In that capacity he compiled budgets, presented them to congress, and handled general administrative problems in the West.

Outstanding among his special interests in park problems was his vigorous participation in programs launched to conserve and reëstablish the native fauna of national parks. He gained an intimate understanding of the needs of American wild life and actively engaged in attempts to supply its wants. He allied himself with such organizations as the National Geographic Society, the American Game Protective Association, the American Forestry Association, the American Bison Society, the American Society of Mammalogists, the Boone and Crockett Club, the Save-the-Redwoods League, and the Sierra Club. He became an expressive factor in American conservation and in his own domain, the national parks, practiced what he preached. He recognized the importance of ecological study of the great wilderness areas, with the safety of which he was charged, and pressed into service a special investigator to work on Yellowstone mammal problems. Later he seized upon the opportunity to extend this research to all parks. In keeping with his desire to assemble scientific data for the preservation of fauna and flora, he had an ambition to popularize the natural sciences as exemplified in the varied park wonderlands. He engaged actively in the development of plans for the museum, lecture, and guide service which today distinguishes the national parks as educational centers as well as pleasure grounds.

Upon the resignation of Director Mather in 1929, it was but natural that Albright should succeed him. He entered into the Yosemite administrative scheme by actual residence in the park and study of its problems. From the Yosemite personnel he drew new executives for other parks, field officers for the service at large, and administrative assistants for his Washington office. He turned to Crater Lake National Park to obtain a superintendent who would succeed Lewis. Colonel C. G. Thomson had distinguished himself as the chief executive of Crater Lake and in 1929 was called to Yosemite.

Some of the developments in Yosemite for which Thomson was largely responsible included the construction and improvements of the Wawona Road and Tunnel, improvement of the Glacier Point Road, commencement of the Big Oak Flat Road and Tioga Road realignment, the installation of improved water systems at the Mariposa Big Trees, Wawona, and Tuolumne Meadows, construction of the new Government Utility Building, and many smaller projects. Such important land acquisition programs as the Wawona Basin project and the Carl Inn sugar pine addition constituted heavy administrative responsibilities imposed upon the superintendent’s office during his regime. The establishment of “emergency programs,” C.C.C., C.W.A., W.P.A., and P.W.A., greatly expanded the developmental activities in the park after 1938, and the inclusion of the Devils Postpile National Monument and Joshua Tree National Monument in the Yosemite administrative scheme increased the duties of the superintendent.

In 1937, Colonel Thomson was stricken by a heart ailment and died in the Lewis Memorial Hospital on March 23. In eulogy, Frank A. Kittredge said:

“Colonel Thomson has, through his dynamic personality and energy and the wealth of his experience, been an influence and inspiration not only to the thousands of Park visitors with whom he has had personal contact, but especially to the Park Service itself. His keen sense of the fitness and desire for the harmony of things in the national parks has made itself felt in the design of every road, every structure, and every physical development in the Park. He recognized the importance and practicability of restricting and harmonizing necessary roads and structures into a natural blending of the surroundings. He has set a standard of beauty and symmetry in construction which has been carried beyond the limits of Yosemite into the entire National Park system. The harmony of the necessary man-made developments and the unspoiled beauty of the Yosemite Valley attest to the Colonel’s injection of his refinement of thought and forceful personality, into even the everlasting granite itself of the Yosemite he loved so well.”

In June, 1937, Lawrence Campbell Merriam, a native Californian, was transferred to the superintendency of Yosemite National Park. He had received a degree in forestry from the University of California in 1921, had become a forest engineer, and had later gone into emergency conservation work in the state parks throughout the United States. Upon the death of Thomson, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes appointed Merriam Senior Conservationist in the National Park Service and designated him Acting Superintendent of Yosemite.

During his four years as the chief executive of the park he renewed the service’s efforts to restore the natural appearance of the valley, and modified the master plan to provide suitable areas for the operators’ utilities.

In August, 1941, Merriam became Regional Director of Region Two, National Park Service, with headquarters at Omaha, Nebraska. Frank A. Kittredge succeeded him in Yosemite.

During World War I, Kittredge served as an officer in the Army Corps of Engineers and saw service in France. Afterward, while with the Bureau of Public Roads, he was identified with park work; he made the location survey of the Going-to-the-Sun Highway in Glacier National Park, did the first road engineering in Hawaii National Park, and devoted his attention to national park road matters handled by the Bureau.

In 1927, Kittredge was appointed chief engineer of the National Park Service and continued in that capacity for ten years, when he was made Regional Director, Region Four, a position involving supervision over Park Service programs in Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Nevada, and Utah; Glacier National Park in Montana; and the territories of Alaska and Hawaii. In August, 1940, he was made Superintendent of Grand Canyon National Park, from which position he was transferred in 1941 to the chief executive position in Yosemite National Park. In all this varied experience with the scenic masterpieces of the national park system, Frank Kittredge maintained a sincerity of purpose in safeguarding the natural and historic values of the parks.

As was true of Mather and Albright, succeeding directors of the National Park Service have taken personal interest and active part in the management of Yosemite National Park. On July 17, 1933, Arno B. Cammerer, formerly Associate Director, succeeded Albright in the Washington post. During his incumbency, 1933-1940, the national park system increased from 128 areas to 204 units, and in addition to regular appropriations, nearly 200 million dollars was expended by the Service in connection with the programs of the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Public Works Administration, and the Emergency Relief Appropriation acts. Under Cammerer’s directorship, five C.C.C. camps were established in Yosemite National Park. With the help of C.C.C., C.W.A., and P.W.A., many management and construction projects in the park were advanced far ahead of regular schedule. The Wawona Road tunnel project was completed, and notable progress was made in constructing the Tioga and Big Oak Flat roads on modern standards. Winter use of the park increased mightily, and the Yosemite Park and Curry Company developed the Badger Pass ski center in accordance with Service plans.

Because of failing health, Gammerer resigned as Director in 1940, and Newton B. Drury, a Californian and a member of the Yosemite Advisory Board, was appointed to the position on June 19, 1940. Since 1919, Drury had been a leader in the movement to preserve distinctive areas for park purposes. As executive head of the Save-the-Redwoods League, he had become a nationally recognized authority on park and conservation affairs and was intimately acquainted with the problems of Yosemite National Park through personal study. The normal problems of the park and of the Service, generally, were greatly complicated by the circumstances resulting from World War II, and the years 1942-1945 were probably the most critical in the history of national parks. But in spite of pressure exerted by production interests and those who sought to capitalize on the park’s assets under the guise of “war necessity,” the natural values of Yosemite were held inviolate. And it is to the everlasting credit of Director Drury and his staff and associates in central offices and the field that during the years of all-out warfare serious inroads were nowhere made upon national park values.

Each year, more than a half million people benefit by the great park’s offerings, and each year witnesses new demands for expansion of public utilities provided by the operators and the Government. To meet these demands and at the same time guarantee “benefit and enjoyment” of Yosemite values for future generations of visitors is one of the most exacting tasks engaged in by public servants anywhere.

One hundred fourteen years have elapsed since the explorers in Joseph Walker’s party first made their way to some point on the north rim of Yosemite Valley and beheld a tremendous scene beneath them. It is to be hoped that the Yosemite visitor today will have his enjoyment of Yosemite National Park somehow enhanced by the recorded story of the human events during the past century, particularly by the story of the human effort that made Yosemite accessible to him, but not too accessible.

Yosemite, like other national parks, has its master plan. Upon it is set down in rather definite form the conception of the park staff of needs for physical improvements. This prescription is reviewed by technicians and executives in central offices and made to delimit the maximum development necessary to meet the requirements of staff and public. The master plan also contains an analysis of the inspirational and recreational experiences which attract the multitude of visitors to the park. As might be expected this analysis of Yosemite’s offerings points to the fact that one of the notable values of the reservation is found in its capacity to stimulate pride in and understanding of the heritage of natural beauty preserved within the park’s boundaries. Another important value is indicated in the capacity of the park to serve as a repository of scientific treasures. In this last-named role as “museum of the out-of-doors,” Yosemite National Park reasonably may be expected to become increasingly important as the less protected areas of the Sierra Nevada are more and more encroached upon by exploiters. The exploiters are not always concerned with livestock, minerals, or timber. The aggressiveness of those who cater to recreation seekers—even of the recreation seekers themselves—constitutes a force to be reckoned with, and this group particularly lays siege to the structure of National Park Service conservatism.

It is well that the visitor to this and other national parks extend his ken. We know something of what has happened since 1833. But what will have happened to the Yosemite region by the year 2033 A.D., two hundred years after white man’s first glimpse of the valley? Will the men of great enterprise have built “ladders touching the sky, changing the face of the universe and the very color of the stars?” Or will there still be a remnant of mountain sanctuary, where the handiwork of today’s and tomorrow’s visitors will be as hard to discern as Joe Walker’s footsteps are to trace?

|

Next: Documents • Contents • Previous: Interpreters

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/one_hundred_years_in_yosemite/guardians.html